Abstract

Background

It is customary for fluids and/or food to be withheld for a period of time after abdominal operations. After caesarean section, practices vary considerably. These discrepancies raise concern as to the bases of different practices.

Objectives

To assess the effect of early versus delayed introduction of fluids and/or food after caesarean section.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group trials register (January 2002) and the Cochrane Controlled Trials Register (The Cochrane Library, Issue 4, 2001).

Selection criteria

Clinical trials with random allocation comparing early versus delayed oral fluids and/or food after caesarean section were considered. The participants were women within the first 24 hours after caesarean section. The criteria for 'early' feeding were as defined by the individual trial authors ‐ usually within six to eight hours of surgery.

Data collection and analysis

Trials considered were evaluated for methodological quality and appropriateness for inclusion. For dichotomous data, relative risks and 95% confidence intervals were calculated. Continuous data were compared using weighted mean difference and 95% confidence interval. Sub‐group analyses were performed for general anaesthesia, regional analgesia and where anaesthesia was mixed or undefined.

Main results

Of 12 studies considered, six were included in this review. Four were excluded and two are pending further information. The methodological quality of the studies was variable. Only one to three studies contributed usable data to each outcome. Three studies were limited to surgery under regional analgesia, while three included both regional analgesia and general anaesthesia.

Early oral fluids or food were associated with: reduced time to first food intake (one study, 118 women; the intervention was a slush diet and food was introduced according to clinical parameters; weighted mean difference ‐7.20 hours, 95% confidence interval ‐13.26 to ‐1.14); reduced time to return of bowel sounds (one study, 118 women; ‐4.30 hours, ‐6.78 to ‐1.82); reduced postoperative hospital stay following surgery under regional analgesia (two studies, 220 women; ‐0.75 days, ‐1.37 to ‐0.12 ‐ random effects model); and a trend to reduced abdominal distension (three studies, 369 women; relative risk 0.78, 95% confidence interval 0.55 to 1.11). No significant differences were identified with respect to nausea, vomiting, time to bowel action/ passing flatus, paralytic ileus and number of analgesic doses.

Authors' conclusions

There was no evidence from the limited randomised trials reviewed, to justify a policy of withholding oral fluids after uncomplicatedcaesarean section. Further research is justified.

Plain language summary

Early compared with delayed oral fluids and food after caesarean section

Drinking and eating again soon after caesarean section does not seem to cause women any problems, and may even speed recovery.

There is a lot of variation in policies about when women are allowed to eat or drink after caesarean section. In some hospitals, women are not allowed to have food or fluids for more than 24 hours after the operation, in the belief that it might take a while for the bowels to settle down after abdominal surgery. However, caesarean section may not disrupt bowel function at all. The review found the evidence from trials does not justify withholding food and drink after uncomplicated caesarean section. There is some evidence, although not strong, that early food and drink might speed bowel recovery.

Background

After general abdominal surgery, it is customary for the patient to take no fluid or food by mouth for a specific period of time, or until the return of bowel function as evidenced by propulsive bowel sounds or the passing of flatus or stool. After caesarean section, practices vary considerably between institutions and individual practitioners, ranging from early oral fluids or food to delayed introduction of oral fluids and food which may be after 24 hours or more. These discrepancies raise concern as to the bases of the different practices. 'Standing orders' may become accepted as part of everyday practice without their validity being questioned. The practice of allowing early oral fluids or food after caesarean section is often based on the assumption that the bowels are not usually exposed or handled during caesarean section, and one would therefore not expect bowel function to be disturbed.

It has been suggested that, even following bowel surgery, bowel sounds change in character but bowel function continues uninterrupted. One study suggested that perioperative nutritional status is of more importance to wound healing than the overall nutritional status (Burrows 1995). In spite of these reports, the tradition of withholding or delaying the intake of fluids immediately postoperatively has been practiced without supportive evidence (Guedj 1991). Ingam et al and Ryan et al, quoted in Guedj 1991, report that gastro‐intestinal function returns soon after abdominal surgery.

Opponents of this view argue that caesarean section is a major operation with a risk of complications arising from giving oral fluids or food soon after surgery. Kramer 1996 believe that abdominal surgery abolishes normal bowel motility immediately post operatively and the onset of bowel function is influenced by the type of surgery performed; and that there may be many factors contributing to paralytic ileus (decreased or absence of intestinal peristalsis following abdominal surgery characterised by abdominal tenderness and distension, absence of bowel sounds, lack of flatus and by nausea and vomiting) other than early feeding, such as neural and hormonal factors, involvement of the sympathetic and the parasympathetic nervous system, use of narcotics and the type of anaesthetic agents used.

According to Bennett 1999, food after caesarean section must not be allowed until bowel sounds are heard, as the woman is at risk of developing paralytic ileus due to handling of the bowel. They recommend that fluids should be gradually introduced followed by light diet. Sellers 1993 recommends that for the first 12 to 24 hours, food and fluids should be withheld. After this period, graded oral fluids can be given until full fluids are tolerated at about the second day post operatively. It is only when bowel sounds are heard and flatus is passed that regular diet can be allowed on about the third postoperative day (Sellers 1993).

Sweet 1997 suggests that fluids can be allowed soon after operation and a light diet started when the woman feels ready to eat. It is only when the surgeon, for one reason or the other, requests that food be withheld until bowel sounds are heard, that the woman may be refused food. According to Gabbe 1996, oral fluids are well tolerated the day after surgery, even if the woman has diminished bowel sounds and does not pass flatus. It is only when there have been extensive intra abdominal manipulations or sepsis that oral fluids may be withheld.

Knuppel 1993 recommend that food and fluids be withheld on the day of the operation. Clear fluids can be offered the next day, thereafter full fluids and then a regular diet can be commenced. Alternatively, clear hot liquids can be given to women as early as one and a half hours after general anaesthesia or immediately after caesarean section if a regional block was used. If these fluids are tolerated without difficulty, a regular diet may be offered at the next feeding if the patient desires it.

These authors suggest very different alternatives. This calls into question the basis of delaying oral fluids and food after caesarean section.

We are not aware of research demonstrating harm from early introduction of oral fluids and food after caesarean section. There should be adequate evidence to support any medical intervention. Even if healthy people can tolerate starvation without any negative effects, this does not account for the woman's discomfort (Burrows 1995). In view of the lack of clear justification for the traditional policy of withholding oral fluids and food after caesarean section and the discomfort caused to women by this policy, some of whom may have been without food during labour, a review of the relevant evidence is justified.

Objectives

To assess the effects of early versus delayed introduction of oral fluids or food or both, following caesarean section. Early introduction was regarded as the intervention and delayed introduction the control (conventional) method.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Clinical trials comparing the effect of early versus delayed introduction of oral fluids and/or food following caesarean section on clinically meaningful outcomes; random allocation to treatment and control groups, with adequate allocation concealment; violations of allocated management and exclusions after allocation not sufficient to materially affect outcomes.

Types of participants

Women within the first 24 hours after caesarean section who are not diabetic.

Types of interventions

Delayed giving of oral fluids and food after caesarean section, as defined by trial authors. Early oral fluids after caesarean section, as defined by trial authors (usually less than six hours). Early oral fluids and food after caesarean section, as defined by trial authors (usually less than six to eight hours).

Types of outcome measures

Nausea, vomiting, crampy abdominal pain, bloating, abdominal distension, presence of bowel action on the third post operative day, delayed return of bowel sounds and bowel action, ketosis, blood sugar level, duration of intravenous fluids, breastfeeding success, woman's satisfaction, fatigue, need for analgesia, ambulation and time spent in hospital.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

This review draws on the search strategy developed for the Pregnancy and Childbirth Group as a whole. The full list of journals and conference proceedings as well as the search strategies for the electronic databases, which are searched by the group on behalf of its reviewers, are described in detail in the 'Search strategies for the identification of studies' section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group. Briefly, the Group searches on a regular basis MEDLINE, the Cochrane Controlled Trials Register and reviews the Contents tables of a further 38 relevant journals received via ZETOC, an electronic current awareness service.

Relevant trials, which are identified through the Group's search strategy, are entered into the group's specialised register of controlled trials. Please see Review Group's details for more information. Date of last search: January 2002.

In addition, the Cochrane Controlled Trials Register (The Cochrane Library, Issue 4, 2001) was searched using the search strategy inAppendix 1.

Data collection and analysis

Trials under consideration were evaluated for methodological quality and appropriateness for inclusion according to the prestated selection criteria, without consideration of their results. Individual outcome data were included in the analysis if they met the prestated criteria in 'Types of outcome measures'. Included trial data were processed as described in Clarke 2000.

Data were extracted from the sources and entered onto the Review Manager (RevMan 2000) computer software, checked for accuracy, and analysed using the RevMan software. For dichotomous data, relative risks and 95% confidence intervals were calculated, and in the absence of heterogeneity, results were pooled using a fixed effects model. Continuous data were compared using weighted mean differences and 95% confidence intervals.

Where appropriate, sub‐group analyses were performed for the following:

regional analgesia; general anaesthesia; anaesthesia mixed or undefined;

uncomplicated caesarean sections; complicated caesarean sections (e.g. freeing of intraperitoneal adhesions, additional intraabdominal procedures excluding tubal ligation);

oral fluids only; oral fluids and food;

elective caesarean section; emergency caesarean section.

Results

Description of studies

Of 12 studies considered, six were suitable for inclusion, four were excluded because allocation was by alternation (Al‐Takroni 1999; Soriano 1996) or according to hospital registration number (Benzineb 1995), or because the objective was not relevant to this review (Sunshine 1997); one is pending further information from the trial authors and one is available only in abstract form (Farine 2001). Of the six included studies, three included women with regional analgesia, one included both regional and general, and two did not specify the method of anaesthesia.

Risk of bias in included studies

The methodological quality of the studies overall was variable. In three studies (Burrows 1995; Kramer 1996; Patolia 2001) allocation was by sealed opaque envelopes. In one of these the envelopes were shuffled (Burrows 1995) and in the other two a computer randomisation sequence was used. In one study (Weinstein 1993) a computer‐generated sequence was used, but the method was not specified, and two (Guedj 1991; Pruitt 2000) specified only that the allocation was 'random'. Studies using alternate allocation or hospital numbers were excluded.

In one study (Kramer 1996), 41 women were not offered participation by the staff. The discrepancy between the final group sizes (109 control versus 91 treatment) is rather large to have arisen by chance, and raises the possibility that withdrawals from the two groups may have been unbalanced, and that selection bias may have been introduced. Sensitivity analysis excluding this trial did not influence the overall results.

Effects of interventions

Three studies were limited to surgery under regional analgesia (Burrows 1995, Guedj 1991 and Patolia 2001), while three included both regional analgesia and general anaesthesia.

Of the outcomes with data available, the number of studies contributing usable data ranged only from one to three. There is thus potential for the effect of reporting bias in these results.

Early oral fluids or food were associated with:

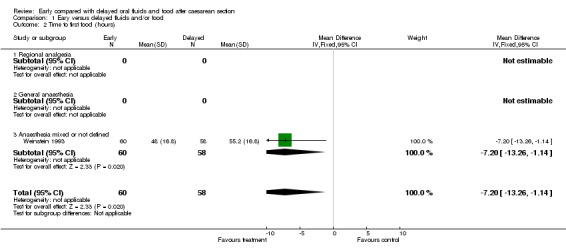

Reduced time to first food intake (one study, 118 women; weighted mean difference ‐7.20 hours, 95% confidence interval ‐13.26 to ‐1.14). The intervention was an early slush diet, and the introduction of solid fluid was determined by the physician on the basis of clinical symptoms (Weinstein 1993).

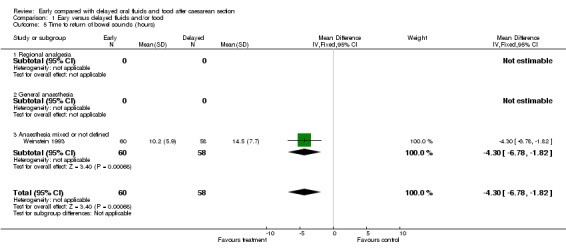

Reduced time to return of bowel sounds (one study, 118 women; ‐4.30 hours, ‐6.78 to ‐1.82).

Reduced postoperative hospital stay following surgery under regional analgesia (two studies, 220 women; ‐0.75 days, ‐1.37 to ‐0.12; random effects model).

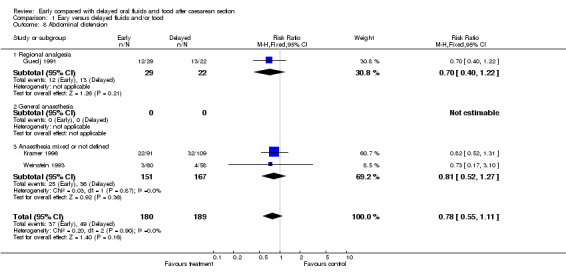

A trend to reduced abdominal distension (three studies, 369 women; relative risk 0.78, 95% confidence interval 0.55 to 1.11).

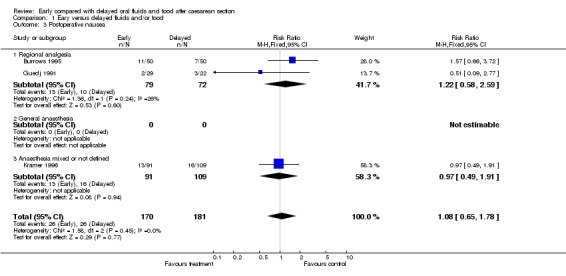

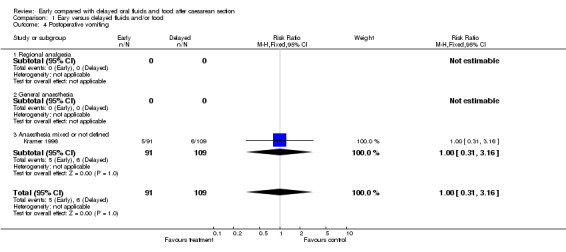

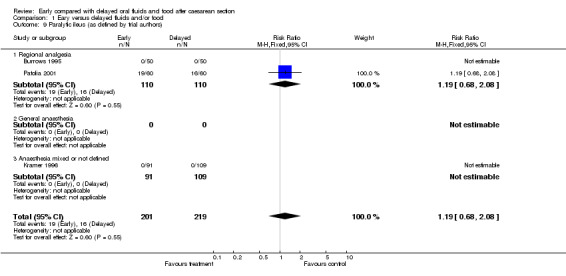

There were no significant differences with respect to: postoperative nausea; postoperative vomiting; time to bowel action; time to passing flatus; paralytic ileus; and number of analgesic doses postoperatively.

The reduction in hospital stay was found only in the studies limited to surgery under regional analgesia (Burrows 1995 and Patolia 2001). Because of significant heterogeneity, a random effects model was used for this analysis.

In the early feeding group, one study allowed fluids only (Guedj 1991), one allowed a slush type diet (Weinstein 1993) and the others allowed fluids and solid food. There were insufficient data to determine whether there were differences in outcomes between those receiving early fluids only and those receiving early solids as well.

It was not possible from the data to determine whether the results differed between women undergoing caesarean section during labour or as an elective procedure.

Discussion

The data should be interpreted with caution because of the variable methodological quality of the studies and the fact that data for individual outcomes are contributed by a limited number of studies. However, there is consistency in that all the outcomes which show significant differences are in favour of the early feeding group. No disadvantages of early oral fluids or food are identified in the studies reviewed. However, it should be borne in mind that the overall numbers studied were too small to exclude the possibility of rare adverse events.

No data were available on outcomes such as the duration of intravenous hydration, biochemical changes, the women's satisfaction, fatigue and breastfeeding initiation and success.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

This review, though having several limitations, has found no evidence from randomised trials to justify a policy of restricting oral fluids or food following uncomplicated caesarean section, except within the context of further well‐designed trials.

Implications for research.

Further research is needed to confirm the findings of these small studies by means of larger, more methodologically sound trials, and to investigate the question of feeding following complicated caesarean section. Future studies should include as outcomes those listed in this review, particularly the question of the women's satisfaction, fatigue and breastfeeding success.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 2 September 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

Acknowledgements

HRP ‐ UNDP/UNFPA/WHO/World Bank Special Programme in Human Reproduction, Geneva for support to Lindeka Mangesi to present this review at the Africa Midwives' Network Conference, 10‐13 December 2001, Arusha, Tanzania.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategy

#1 (ORAL near FEED*) #2 (ORAL near FLUID*) #3 (ORAL near HYDRAT*) #4 (ORAL near INTAKE) #5 EAT* #6 DRINK* #7 FOOD #8 CESAR* #9 CAESAR* #10 CESAREAN‐SECTION*:ME #11 ((((((#1 or #2) or #3) or #4) or #5) or #6) or #7) #12 ((#8 or #9) or #10) #13 (#11 and #12)

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Eary versus delayed fluids and/or food.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Time to first oral fluid (hours) | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 1.1 Regional analgesia | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 1.2 General anaesthesia | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 1.3 Anaesthesia mixed or not defined | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2 Time to first food (hours) | 1 | 118 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐7.20 [‐13.26, ‐1.14] |

| 2.1 Regional analgesia | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2.2 General anaesthesia | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 2.3 Anaesthesia mixed or not defined | 1 | 118 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐7.20 [‐13.26, ‐1.14] |

| 3 Postoperative nausea | 3 | 351 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.08 [0.65, 1.78] |

| 3.1 Regional analgesia | 2 | 151 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.22 [0.58, 2.59] |

| 3.2 General anaesthesia | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3.3 Anaesthesia mixed or not defined | 1 | 200 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.49, 1.91] |

| 4 Postoperative vomiting | 1 | 200 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.31, 3.16] |

| 4.1 Regional analgesia | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4.2 General anaesthesia | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4.3 Anaesthesia mixed or not defined | 1 | 200 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.31, 3.16] |

| 5 Time to return of bowel sounds (hours) | 1 | 118 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐4.30 [‐6.78, ‐1.82] |

| 5.1 Regional analgesia | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 5.2 General anaesthesia | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 5.3 Anaesthesia mixed or not defined | 1 | 118 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐4.30 [‐6.78, ‐1.82] |

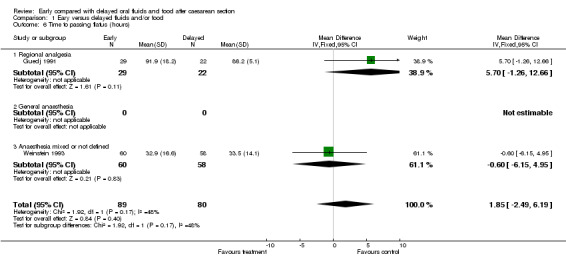

| 6 Time to passing flatus (hours) | 2 | 169 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.85 [‐2.49, 6.19] |

| 6.1 Regional analgesia | 1 | 51 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 5.70 [‐1.26, 12.66] |

| 6.2 General anaesthesia | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 6.3 Anaesthesia mixed or not defined | 1 | 118 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.60 [‐6.15, 4.95] |

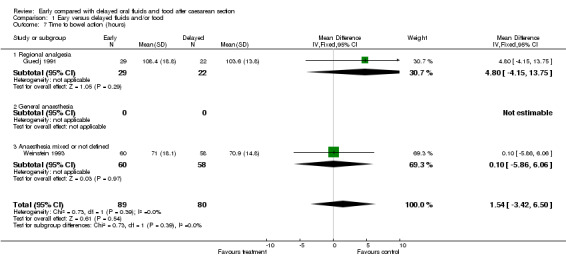

| 7 Time to bowel action (hours) | 2 | 169 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.54 [‐3.42, 6.50] |

| 7.1 Regional analgesia | 1 | 51 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.80 [‐4.15, 13.75] |

| 7.2 General anaesthesia | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 7.3 Anaesthesia mixed or not defined | 1 | 118 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.10 [‐5.86, 6.06] |

| 8 Abdominal distension | 3 | 369 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.78 [0.55, 1.11] |

| 8.1 Regional analgesia | 1 | 51 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.70 [0.40, 1.22] |

| 8.2 General anaesthesia | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 8.3 Anaesthesia mixed or not defined | 2 | 318 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.81 [0.52, 1.27] |

| 9 Paralytic ileus (as defined by trial authors) | 3 | 420 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.19 [0.68, 2.08] |

| 9.1 Regional analgesia | 2 | 220 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.19 [0.68, 2.08] |

| 9.2 General anaesthesia | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 9.3 Anaesthesia mixed or not defined | 1 | 200 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 10 Ketosis | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 10.1 Regional analgesia | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 10.2 General anaesthesia | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 10.3 Anaesthesia mixed or not defined | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 11 Hypoglycaemia | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 11.1 Regional analgesia | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 11.2 General anaesthesia | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 11.3 Anaesthesia mixed or not defined | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 12 Duration of intravenous fluids (hours) | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 12.1 Regional analgesia | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 12.2 General anaesthesia | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 12.3 Anaesthesia mixed or not defined | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

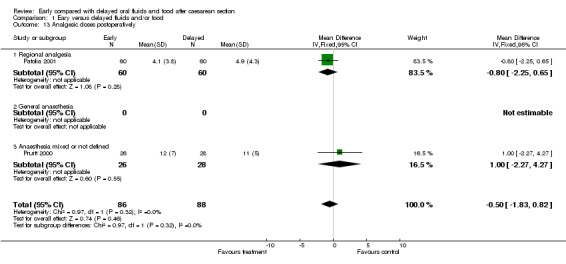

| 13 Analgesic doses postoperatively | 2 | 174 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.50 [‐1.83, 0.82] |

| 13.1 Regional analgesia | 1 | 120 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.80 [‐2.25, 0.65] |

| 13.2 General anaesthesia | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 13.3 Anaesthesia mixed or not defined | 1 | 54 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [‐2.27, 4.27] |

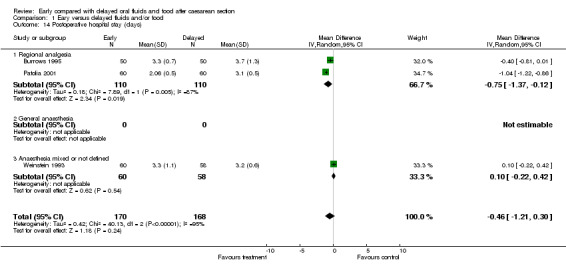

| 14 Postoperative hospital stay (days) | 3 | 338 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.46 [‐1.21, 0.30] |

| 14.1 Regional analgesia | 2 | 220 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.75 [‐1.37, ‐0.12] |

| 14.2 General anaesthesia | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 14.3 Anaesthesia mixed or not defined | 1 | 118 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.10 [‐0.22, 0.42] |

| 15 Woman not satisfied | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 15.1 Regional analgesia | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 15.2 General anaesthesia | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 15.3 Anaesthesia mixed or not defined | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 16 Time to first breastfeeding (hours) | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 16.1 Regional analgesia | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 16.2 General anesthesia | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 16.3 Anaesthesia mixed or not defined | 0 | 0 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 17 Breastfeeding not successful (as defined by trial authors) | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 17.1 Regional analgesia | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 17.2 General anaesthesia | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 17.3 Anaesthesia mixed or not defined | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Eary versus delayed fluids and/or food, Outcome 2 Time to first food (hours).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Eary versus delayed fluids and/or food, Outcome 3 Postoperative nausea.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Eary versus delayed fluids and/or food, Outcome 4 Postoperative vomiting.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Eary versus delayed fluids and/or food, Outcome 5 Time to return of bowel sounds (hours).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Eary versus delayed fluids and/or food, Outcome 6 Time to passing flatus (hours).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Eary versus delayed fluids and/or food, Outcome 7 Time to bowel action (hours).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Eary versus delayed fluids and/or food, Outcome 8 Abdominal distension.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Eary versus delayed fluids and/or food, Outcome 9 Paralytic ileus (as defined by trial authors).

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Eary versus delayed fluids and/or food, Outcome 13 Analgesic doses postoperatively.

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Eary versus delayed fluids and/or food, Outcome 14 Postoperative hospital stay (days).

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Burrows 1995.

| Methods | A prospective randomised, controlled study design. Cards containing randomisation assignment and standard analgesic orders in opaque envelopes. Envelopes shuffled and subjects selected an envelope to receive assignment. | |

| Participants | Women from delivery suites prior to caesarean section. All women excluding those receiving general anaesthesia, requiring insulin, having active bowel disease or bowel surgery at caesarean and requiring intensive post operative care for any reason. | |

| Interventions | The group for early feeding received solid foods within 8 hours of surgery. Women instructed not to eat or drink unless they wished to do so. Oral fluids given as needed immediately after surgery. Women in delayed group were given nothing by mouth for a minimum of 12 hours. Had to tolerate clear fluids before advancing to solid foods. | |

| Outcomes | Return of bowel sounds or passage of flatus; use of patient controlled injectable narcotics (early: 66 doses of oral narcotics and 129 doses of non steroidals, delayed feeding group had 71 doses of oral narcotic and 120 doses of non steroidals). Post partum endometritis in 16% treatment group and in 30% control group. Bowel action: 28 women had bowel action in early group before end of study and 13 in control group. Maximum minus minimum abdominal girth in the early group was 3.7cm (SD 3.4) and 5.2 (4.1) in the delayed group. | |

| Notes | Study period started on the day of surgery and ended at midnight of post operative day 3 or at discharge, which ever came sooner. Post operative day 0 is the day of surgery and days changed at midnight. Nausea or vomiting measured as one outcome. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | High risk | C ‐ Inadequate |

Guedj 1991.

| Methods | Random allocation. | |

| Participants | Unpremedicated women undergoing caesarean section under epidural anaesthesia (elective or emergency). | |

| Interventions | Early group had immediate unlimited oral intake of water, coffee or tea with sugar. Delayed group fasted for at least 24 hours post operatively. | |

| Outcomes | Post operative nausea and vomiting, onset of peristalsis, rectal gas emission, patient convenience and first bowel movement. In the early group the first flatus was passed on day 2 and in the delayed group the first flatus was passed on day 3. Bowel sounds returned within 12 to 24 hours in all women. The comfort of the women was stated to be greater in the early oral fluid group with less local pain from the drip site. | |

| Notes | Methods not clearly defined. For return of flatus and bowel movements mean values and standard deviations were calculated from the data given. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Kramer 1996.

| Methods | Randomised according to computer‐generated number list. Group assignment placed in sealed envelopes and drawn consecutively. | |

| Participants | Women undergoing caesarean section delivery. Epidural, spinal and general endotracheal anaesthesia used at the discretion of the anaesthetist and consistent with the patient's request. Excluded: women undergoing caesarean hysterectomy or other extensive intra‐abdominal surgery and sick women. | |

| Interventions | Women in early feeding group were given regular diet within 6 hours post operatively. Women in delayed feeding group were given sips of water and ice chips initially, clear fluids when there were bowel sounds and regular diet after passage of flatus or bowel action. | |

| Outcomes | Symptoms suggestive of paralytic ileus: crampy abdominal pain, distension, bloating, nausea or absence of bowel movement before discharge; length of labour; post partum infections; length of hospitalisation; gastro intestinal symptoms. No symptoms of paralytic ileus (In control group 43 (34.9%) out of 109 and in the study group 45 (49.5%) out of 91); the need for pain medication: 75% in the study group used non steroidal pain medication at least once compared with 61% of women in the control group. Two women in the control group and 5 women in the study group had a post operative stay of 5 days or longer for reasons other than paralytic ileus. | |

| Notes | Twenty‐two women declined participation and 221 women were enrolled. Out of 241, 41 were not offered participation by staff. There were 200 women in the study, 109 in the control group and 91 in the treatment group. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Patolia 2001.

| Methods | Computer generated number list in consecutively numbered opaque envelopes | |

| Participants | Women due for caesarean section (elective or emergency). Exclusion criteria: General anaesthesia, on magnesium sulphate, intra‐operative bowel surgery and bowel injury, gastro‐intestinal or medical conditions excluding early feeding. | |

| Interventions | Early feeding: solid food within 8 hours of surgery versus traditional feeding: nothing by mouth for 12‐24 hours, clear fluids up to 24 hours and regular diet 24‐48 hours if liquid tolerated and flatus or stool passed, liquid diet if flatus not passed, in which case full diet was started after 48‐72 hours. Solid food given to early group after 5.0 (SD 1.2) versus 40 (10.6) hours for traditional group. | |

| Outcomes | Primary: Mild ileus symptoms (anorexia, abdominal cramping, non‐persistant nausea and or vomiting). Secondary: severe ileus (abdominal distension, >3 episodes of vomiting in 24 hours and inability to tolerate oral fluids or requiring nasogastric tube or abdominal X‐ray) (0/60 versus 1/60), post operative febrile morbidity (oral temperature >/=37 degrees celsius two times at least 6 hours apart, 24 hours post surgery; post operative time to bowel movement: median 34.5 (IQR 25‐49) versus 51 (43‐62) hours; hospital admission 1/60 versus 2/60; analgesia. | |

| Notes | Exact time of starting oral fluids in the delayed group not clear. Of 124 enrolled, 2 withdrew and 2 were excluded because of inadequate data. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Pruitt 2000.

| Methods | Random assignment. | |

| Participants | Low risk women consenting after caesarean section delivery. | |

| Interventions | The early feeding group began solid foods 6 hours after surgery. Women in the delayed feeding group took nothing by mouth on the day of surgery, liquids on day one and solids after flatus was passed. | |

| Outcomes | Nausea, vomiting, gas pain, number of requests for analgesics and diet satisfaction. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Weinstein 1993.

| Methods | Random assignment by a computer generated list of numbers in a consecutive series. | |

| Participants | Women who were to undergo caesarean section for various reasons. | |

| Interventions | The early feeding group were assigned to PROEF (post operative regimen for oral early feeding) diet. They were given a slush type diet, to be eaten with a straw or with a spoon immediately after surgery and thereafter every 8 hours. This was to be continued until the surgeon believed that the patient should have a regular diet. Delayed feeding group were given sips of water post operatively advancing from clear fluids to regular diet at the discretion of the operating physician. The decision of the physician depended on the abdominal physical findings of the absence of distension, the presence of bowel sounds and the passage of flatus. | |

| Outcomes | Time to first bowel sounds, time to passage of flatus, time to first bowel movement, evidence of abdominal distension, presence of nausea or vomiting, days to regular diet, length of hospital stay, post operative infection. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Al‐Takroni 1999 | Excluded because allocation by alternation, not random. |

| Benzineb 1995 | Allocation according to hospital registration numbers, not random. |

| Soriano 1996 | Allocation by alternation, not random. |

| Sunshine 1997 | Excluded because not relevant to this review. They studied analgesic effectiveness in fed versus starved women after caesarean section. |

Contributions of authors

Lindeka Mangesi prepared the first version of the protocol and the primary data extraction and analysis. Justus Hofmeyr provided mentorship and revised the protocol and final review.

Sources of support

Internal sources

University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa.

East London Hospital Complex, South Africa.

University of Fort Hare, Eastern Cape, South Africa.

External sources

HRP ‐ UNDP/UNFPA/WHO/World Bank Special Programme in Human Reproduction, Geneva, Switzerland.

World Health Organisation (Long‐term Institutional Development Grant), Switzerland.

Declarations of interest

None known.

Edited (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Burrows 1995 {published data only}

- Burrows WR, Gingo AJ, Rose SM, Zwick SI, Kosty DL, Dierker LJ, et al. Safety and efficacy of early post operative solid food consumption after caesarean section. Journal of Reproductive Medicine 1995;40:463‐7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Guedj 1991 {published data only}

- Guedj P, Eldor J, Stark M. Immediate post operative oral rehydration after caesarean section. Asia‐Oceania Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 1991;17(2):125‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kramer 1996 {published data only}

- Kramer RL, Someren JK, Qualls CR, Curet LB. Postoperative management of cesarean patients: the effect of immediate feeding on the incidence of ileus. Obstetrics and Gynecology 1996;88:29‐32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Patolia 2001 {published data only}

- Hilliard R, Patolia DS, Toy EC, Baker B. Early feeding after cesarean delivery. Obstetrics and Gynecology 2000;95(4 Suppl):44S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patolia DS, Hilliard RLM, Toy EC, Baker B. Early feeding after cesarean: randomized trial. Obstetrics and Gynecology 2001;98(1):113‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pruitt 2000 {published data only}

- Pruitt B, Brumfield C, Owen J, Savage K, Cliver S. Early feeding after cesarean: a randomized clinical trial [abstract]. Obstetrics and Gynecology 2000;95(4 Suppl):64S. [Google Scholar]

Weinstein 1993 {published data only}

- Weinstein L, Dyne PL, Duerbeck NB. The PROEF diet ‐ a new postoperative regimen for oral early feeding. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1993;168:128‐31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein L, Dyne PL, Duerbeck NB. The PROEF diet ‐ a new postoperative regimen for oral early feeding. Surgery Gynecology and Obstetrics 1993;177:29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Al‐Takroni 1999 {published data only}

- Al‐Takroni AMB, Parvathi CK, Mendis KBL, Hassan S, Qunaibi AM. Early oral intake after caesarean section performed under general anaesthesia. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 1999;19(1):34‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Benzineb 1995 {published data only}

- Benzineb N, Slim MN, Masmoudi A, Ben Taieb A, Sfar R. The value of realimentation following cesarean section. Revue Francaise de Gynecologie et d Obstetrique 1995;90:281‐5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Soriano 1996 {published data only}

- Soriano D, Dulitzki M, Keidar N, Barkai G, Maschiach S, Seidman DS. Early oral feeding after cesarean section. Obstetrics and Gynecology 1996;87:1006‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sunshine 1997 {published data only}

- Sunshine A, Olsen N, Zighelboim I, Wajdula J. A food interaction study of bromfenac, naproxen sodium and placebo in caesarean section patients. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics 1997;61:PIII‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies awaiting assessment

Al‐Takroni 1997 {published data only}

- Al‐Takroni A, Ansari N. Early oral intake after caesarean section (CS) performed under general anaesthesia. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica 1997;76(Suppl 167:5):14. [Google Scholar]

Farine 2001 {published data only}

- Farine D, Noorwali F, Seaward G, Lubin M, Salenieks M, Karkanis S. Comparison of early and delayed feeding post‐cesarean delivery [abstract]. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2001;184(1):S:194. [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Bennett 1999

- Bennett VR, Brown LK. Myles textbook for midwives. 13th Edition. Toronto: Churchill Livingstone, 1999. [Google Scholar]

Clarke 2000

- Clarke M, Oxman AD, editors. Cochrane Reviewers’ Handbook 4.1 [updated June 2000]. In: Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program]. Version 4.1. Oxford, England: The Cochrane Collaboration, 2000.

Gabbe 1996

- Gabbe SG, Niebyl JR, Simpson JL. Obstetrics: normal and problem pregnancies. 3rd Edition. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1996. [Google Scholar]

Knuppel 1993

- Knuppel RA, Drukker JE. High risk pregnancy: a team approach. 2nd Edition. London: WB Saunders Company, 1993. [Google Scholar]

RevMan 2000 [Computer program]

- The Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager (RevMan). Version 4.1 for Windows. Oxford, England: The Cochrane Collaboration, 2000.

Sellers 1993

- Sellers PM. Midwifery. Vol. 2, Kenwyn: Juta & co. Ltd, 1993. [Google Scholar]

Sweet 1997

- Sweet BR, Tiran D. Mayes' Midwifery. 12th Edition. London: Bailliere Tindall, 1997. [Google Scholar]