Abstract

The homeless population is aging; older homeless adults may be at high risk of experiencing violent victimization. To examine whether homelessness is independently associated with experiencing physical and sexual abuse, we recruited 350 adults, aged 50 and older in Oakland, California, who met criteria for homelessness between July 2013 and June 2014. We interviewed participants at 6-month intervals for 3 years in Oakland about key variables, including housing status. Using generalized estimating equations, we examined whether persistent homelessness in each follow-up period was independently associated with having experienced physical or sexual victimization, after adjusting for known risk factors. The majority of the cohort was men (77.4%) and Black American (79.7%). At baseline, 10.6% had experienced either physical or sexual victimization in the prior 6 months. At 18-month follow-up, 42% of the cohort remained homeless. In adjusted models, persistent homelessness was associated with twice the odds of victimization (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 2.01; 95% confidence interval [CI]: [1.41, 2.87]). Older homeless adults experience high rates of victimization. Re-entering housing reduces this risk. Policymakers should recognize exposure to victimization as a negative consequence of homelessness that may be preventable by housing.

Keywords: sexual assault, elder abuse, community violence, violence exposure

Introduction

People experiencing homelessness have a heightened risk for physical and sexual victimization (i.e., violent victimization; Christensen et al., 2005; Kushel, Evans, Perry, Robertson, & Moss, 2003; Wenzel, Leake, & Gelberg, 2000). High rates of victimization among homeless adults may be due to shared risk factors for homelessness and victimization or due to the dangerous environment of homelessness. Prior experiences of abuse, having mental health and substance use problems, and having limited social support are all associated with both homelessness and victimization (Brown et al., 2016; Judges, Gallant, Yang, & Lee, 2017; Spinelli et al., 2017). Early life victimization increases future victimization through its negative effects on mental health, self-esteem, self-efficacy, and ability to form relationships (Arata, 2006; Culatta, Clay-Warner, Boyle, & Oshri, 2017; DePrince, 2005; Dias, Sales, Mooren, Mota-Cardoso, & Kleber, 2017). Mental health and substance use problems increase the risk of victimization by increasing the chance that people engage in conflictual intimate relationships, exposing individuals to social networks who engage in risky behaviors and distorting perception of risk (Silver, 2006). Poor social support could increase the risk of victimization due to isolation, lack of social capital and reduced autonomy to protect against harm (Acierno et al., 2010; Hwang et al., 2009; Wenzel, Tucker, Elliott, Marshall, & Williamson, 2004). Alternatively, the increased risk of victimization experienced by homeless individuals may be due to risks stemming from the dangerous environment of homelessness. Living in emergency shelters or unsheltered environments is characterized by instability, lack of privacy, lack of choice in where to stay, and the inability to control personal space or maintain distance from harmers, thus increasing the risk of victimization (Kushel et al., 2003).

The median age of single homeless adults is increasing—a growing proportion of adults are aged 50 and older (Montgomery, Cutuli, Evans-Chase, Treglia, & Culhane, 2013). Due to the premature development of geriatric conditions in homeless adults, adults aged 50 and older are considered to be “older adults” (Brown et al., 2017; Brown, Kiely, Bharel, & Mitchell, 2012). Existing studies of victimization in homeless populations were completed prior to the aging of the population (Christensen et al., 2005; Kushel et al., 2003). Little is known about violent victimization in older homeless adults. Although older adults in the general population face a lower risk of victimization than younger adults, less is known about older homeless adults. Older homeless adults may not share the relative protections associated with aging that older adults in the general population experience (Kushel et al., 2003; Morgan & Kena, 2018). Older homeless adults may face additional individual risk factors for victimization. For instance, homeless adults suffer from a high prevalence of functional and cognitive impairments at earlier ages than the general population (Brown et al., 2017). We hypothesize that these may limit capacity to recognize danger and to self-defend (Fang & Yan, 2017; Poole & Rietschlin, 2012; Williams, Racette, Hernandez-Tejada, & Acierno, 2017).

It is not known whether the elevated rates of victimization in homeless adults result from an increased prevalence of risk factors for victimization, or the environment of homelessness. Most prior research on victimization in homeless populations has used cross-sectional research and treated homelessness as a static experience (Dietz & Wright, 2008). Cross-sectional research is not positioned to examine the association between changes in the lived environment and risk of victimization. Homelessness is a dynamic state, marked by entrances and exits (Parsell, Tomaszewski, & Phillips, 2014). This dynamic state allows us to examine the association between changes in housing status and risk of victimization over time in populations that experience homelessness. Therefore, in a prospective cohort study, we enrolled older adults when they were homeless and followed them for 3 years regardless of housing status. Using generalized estimating equation (GEE) models, we examined whether persistent homelessness (vs. regaining housing) was associated with a higher risk for violent victimization, after adjusting for individual risk factors. We hypothesized that homeless older adults would experience a high rate of violent victimization and that persistent homelessness would be independently associated with victimization.

Method

Design Overview

HOPE HOME (Health Outcomes of People Experiencing Homelessness in Older Middle Age) is a prospective cohort study of older homeless adults (Lee et al., 2016). We recruited homeless adults aged 50 and older in Oakland, California, and interviewed participants every 6 months over a period of 3 years (Lee et al., 2016). The institutional review board of the University of California, San Francisco approved the study.

Setting and Participants

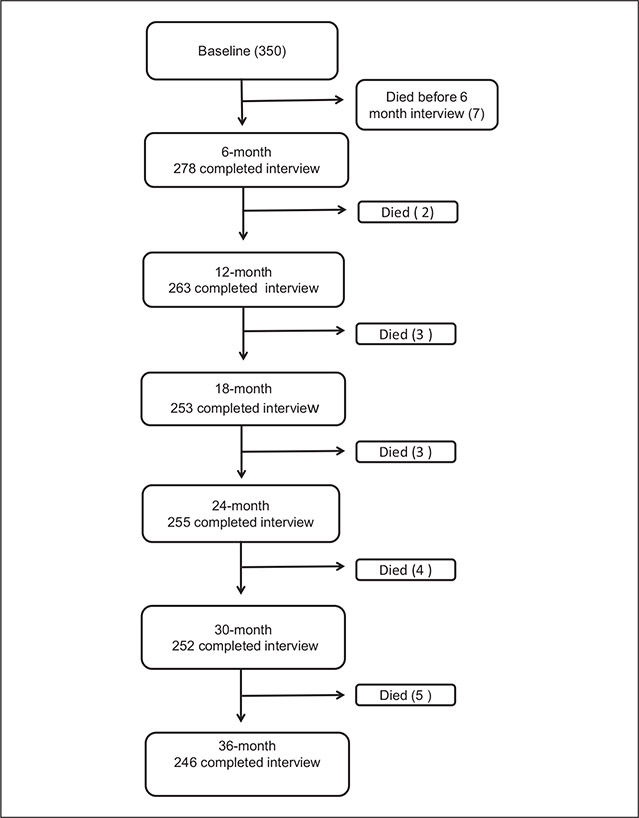

From July 2013 to June 2014, we recruited 350 homeless adults aged 50 years and older from overnight homeless shelters (n = 5), low-cost meal programs (n = 5), a recycling center, and places where unsheltered homeless adults stayed (Figure 1). We constructed our sampling frame to approximate the source population and randomly selected potential participants at each recruitment site (Lee et al., 2016) Individuals were eligible to participate if, at the first interview, they were aged 50 or older, English-speaking, homeless as defined in the federal Homeless Emergency Assistance and Rapid Transitions to Housing (HEARTH) Act and able to give informed consent (Dunn & Jeste, 2001; Homeless Emergency Assistance and Rapid Transition to Housing Act of 2009, 2009). The HEARTH Act is the Federal definition of homelessness. It defines someone as homeless if they (a) lack a fixed residence, (b) reside in a place not typically used for sleeping, or (c) are at imminent risk of losing housing within 14 days.

Figure 1.

Study population recruitment (2013–2014) and follow-up over 36 months, Oakland, California, United States.

Note. The figure shows the number of individuals enrolled at baseline and followed at 6-month intervals over 36-month follow-up. Deaths between each follow-up are noted.

Trained study staff administered a structured enrollment interview and collected participants’ contact information. To ensure follow-up, we asked participants to check-in with study staff monthly. If participants missed two or more check-ins, study staff called contacts and visited places where the participant frequented. We gave participants gift cards to a major retailer: US$25 for the screening and enrollment interview, US$5 for check-ins, and US$15 for follow-up interviews.

Measures

Primary dependent variable: Recent violent victimization.

Our primary dependent variable was having experienced physical or sexual victimization in the prior 6 months. We adapted items from the Straus Conflict Tactics Scale to tailor them to homeless populations, focusing on severe forms of victimization (Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996).

At every interview, we asked “in the past 6 months, have you experienced physical violence by another person using an object like a gun or a knife, or did anyone ever slap, hit, punch, kick, choke, or burn you?” and “Has anyone pressured or forced you to have sexual contact, defined as touching your private parts in a sexual way, making you do something sexual, or making you have sex?” We dichotomized responses at each interview as having recently experienced either physical or sexual victimization.

Primary independent variable: Persistent homelessness.

Our primary independent variable was homelessness at each follow-up interview, as defined by the HEARTH Act (Homeless Emergency Assistance and Rapid Transition to Housing Act of 2009, 2009). At each interview, we determined whether participants met HEARTH criteria for homelessness.

Time constant covariates.

We assessed all time constant variables at baseline. Participants reported their sex and race/ethnicity. Participants reported whether they had experienced early life (before age 18) physical or sexual victimization (any vs. none) (Straus et al., 1996). To assess cognitive function, we administered the Modified Mini-Mental State Examination (3MS); we considered scores 1.5 SD below an age- and education-adjusted reference mean (below the 7th percentile) to be cognitive impairment (Bravo & Hebert, 1997).

Time varying covariates.

We used participant’s date of birth to calculate their age at each interview. We assessed other time varying covariates at each interview. For depressive symptoms, we considered individuals to have moderate-to-severe symptomatology if they scored ≥22 on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (Wong, 2000). To assess functional impairment, we asked participants if they had difficulty performing activities of daily living (ADLs) and considered difficulty performing one or more ADLs as having functional impairment (Katz, 1983).

To assess social support, we asked participants to quantify the number of close confidants (defined as anyone in whom the participant could confide). We categorized these using validated categories (0, 1–5, or ≥6) (Gielen et al., 1994; Gielen, McDonnell, Wu, O’Campo, & Faden, 2001; Riley et al., 2014).

We considered participants who reported drinking ≥6 drinks on one occasion every month as heavy drinkers (Babor, Higgins-Biddle, Saunders, & Monteiro, 2001). We assessed illicit drug use (opioids, methamphetamine, or cocaine) using the World Health Organization Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST; 6-month period; score of ≥4 for one or more substance indicated moderate-to-severe illicit drug use) (Humeniuk, Henry-Edwards, Ali, Poznyak, & Monteiro, 2010).

Descriptive victimization variables.

For descriptive purposes, at the baseline interview, we asked participants if they had ever experienced physical and sexual victimization before and after age 18. We asked participants to report their relationship to the person who committed the victimization: for childhood (i.e., caregiver, someone else, or both) and adulthood (i.e., intimate partner, someone else, or both).

Descriptive demographic variables.

Participants reported their education (i.e., high school diploma/General Educational Development [GED] test equivalency vs. less). We asked participants the age that they first experienced adult homelessness and the time since last stable housing. We assessed self-rated general health (fair or poor vs. good, very good, or excellent). We asked participants to report if a health care provider had ever told them they had coronary artery disease or myocardial infarction; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), emphysema, chronic bronchitis, or asthma; cirrhosis or liver disease; congestive heart failure; stroke or transient ischemic attack; arthritis; diabetes; kidney disease; cancer (excluding non-melanoma skin cancer); or HIV/AIDS. We categorized participants as having 0, 1, 2, or 3 or more chronic conditions (Lee et al., 2016).

Statistical Analysis

We chose independent variables based on prior research. We included variables that we hypothesized would be associated in older homeless adults based on the prior literature. We assessed bivariable associations between recent victimization and a priori independent variables using GEEs. We built our multivariable model by including variables with bivariable Type 3 p values <.20 (two sided) and reduced the model using backwards elimination retaining variables with p values <.05 (two sided) for our final multivariable model. We implemented our models in Stata using complete case analysis and robust confidence intervals (CIs; version 15; Stata Corp., 2017). To examine potential bias due to missed visits, we conducted a sensitivity analysis stratified by those who had completed all interviews versus those missing at least one interview.

To test if our results were robust across differing definitions of homelessness, we re-ran our analysis using a different definition of homelessness as our independent variable, defining homelessness as reporting, in a residential calendar, having spent any nights either unsheltered or in an emergency shelter in the prior 6 months (Tsemberis, McHugo, Williams, Hanrahan, & Stefancic, 2006). We categorized variables (referent: 0 nights) as 1 to 7, 8 to 120, and 121 or more nights.

Results

Participants had a median age of 58 (interquartile range [IQR], 54, 61). A majority of the sample were men (77.4%) and Black (79.7%). One-quarter (25.5%) had completed less than a high school education. Nearly half (43.5%) were aged 50 or older at their first experience of homelessness. Over half (67.2%) lacked stable housing for over a year (Table 1). At the 18-month follow-up interview, 42% of the cohort remained homeless.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Homeless Adults Age >50 Years (N = 350), Oakland, California, United States, 2013–2014.

| Total (N = 350) | Experienced Physical/Sexual Victimization Within Past 6 Months (N = 37) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographics and life history | ||

| Age, Median years (IQR) | 58.0 (54.0, 61) | 57.0 (53.0, 59.0) |

| Men, No. (%) | 270 (77.4) | 27 (73.0) |

| Race/ethnicity, No. (%) | ||

| Black | 278 (79.7) | 23 (62.2) |

| White | 38 (10.9) | 9 (24.3) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 16 (4.6) | 2 (5.4) |

| Mixed/Other | 17 (4.9) | 3 (8.1) |

| Less than high school education, No. (%) | 89 (25.5) | 9 (24.3) |

| Age at first homelessness | ||

| ≥50 years | 152 (43.5) | 17 (46.0) |

| ≥1 years since last stable housing | 233 (67.2) | 24 (64.9) |

| Number of nights spent in unsheltered settings or emergency shelter, past 6 months | ||

| 0 | 10 (2.9) | 1 (2.7) |

| 1–7 | 13 (3.7) | 1 (2.7) |

| 8–120 | 137 (39.3) | 14 (37.8) |

| ≥121 | 189 (54.1) | 21 (56.8) |

| Health status, No. (%) | ||

| Fair or Poor | 194 (55.6) | 24 (64.9) |

| Chronic conditions | ||

| 0 | 61 (17.5) | 7 (18.9) |

| 1–2 | 183 (52.3) | 13 (35.1) |

| ≥3 | 115 (33.0) | 17 (46.0) |

| Mental health and functional status | ||

| Moderate-to-severe depressive symptomatology, No. (%)a | 133 (38.3) | 23 (62.2) |

| Cognitive impairment, No. (%)b | 89 (25.6) | 9 (24.3) |

| ≥1 ADL impairment, No. (%) | 135 (38.7) | 20 (54.1) |

| Social support, No. (%) | ||

| 0 confidants | 112 (32.3) | 16 (43.2) |

| 1–5 confidants | 205 (59.1) | 18 (48.7) |

| ≥6 confidants | 30 (8.7) | 3 (8.1) |

| Alcohol and illicit substance use | ||

| Heavy drinkingc | 39 (11.2) | 5 (13.5) |

| Moderate-to-severe illicit drug use, No. (%)d | 177 (50.7) | 24 (64.9) |

| Experienced victimization before age 18 | ||

| Physical | 116 (33.3) | 15 (40.5) |

| Sexual | 46 (13.2) | 7 (18.9) |

| Physical or sexual | 132 (37.8) | 17 (46.0) |

| Victimization in adulthood (age 18 or later) | ||

| Physical | 178 (51.2) | 37 (100.0) |

| Sexual | 46 (13.2) | 11 (29.7) |

| Physical or sexual | 186 (53.3) | 37 (100.0) |

| Any victimization during lifetime | ||

| Physical | 218 (62.6) | 37 (100.0) |

| Sexual | 70 (20.1) | 12 (32.4) |

| Physical or sexual | 231 (66.2) | 37 (100.0) |

| Past 6-month victimization | ||

| Physical | 35 (10.1) | 35 (94.6) |

| Sexual | 6 (1.7) | 6 (16.2) |

| Physical or sexual | 37 (10.6) | 37 (100.0) |

Note. No. = number; CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; IQR = interquartile range.

CES-D score ≥22.

Cognitive impairment defined as a Modified Mini-Mental State Examination score below the 7th percentile (i.e., 1.5 SD below the demographically adjusted cohort mean).

Six or more drinks on one occasion at least once monthly.

Moderate-to-severe illicit drug use past 6 months defined as a World Health Organization Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test score for cocaine, methamphetamines, or opioids of ≥4 (range 0–39; higher scores indicate more problems).

At baseline, 11.2% reported heavy drinking; approximately half (50.7%) met the criteria for moderate-to-severe risk illicit drug use. Over one third of participants had moderate-to-severe depressive symptomatology (38.3%). Over half had poor self-rated health (55.6%) and one third had three or more chronic conditions (33.0%). One quarter had cognitive impairment (25.6%) and over one third had ADL impairment (38.7%).

Lifetime, Early Life, and Adulthood Victimization

At baseline, 10.1% of participants reported experiencing physical assault in the prior 6 months; 1.7% reported sexual assault and 10.6% reported experiencing either physical or sexual assault (Table 1). Over half of participants (66.2%) reported experiencing either physical (62.6%) or sexual (20.1%) victimization in their lifetime.

Over one third (37.8%) reported having been either physically (33.3%) or sexually (13.2%) assaulted before the age of 18 (Table 1) Over half, 53.3%, reported having experienced violent victimization during their adulthood, 51.2% reported physical victimization and reported 13.2% sexual assault. Participants were more likely to report that someone other than an intimate partner (in adulthood) or caregiver (in childhood) victimized them (Table 2).

Table 2.

Baseline Victimization Prevalence and Relationship to Harmer Among Homeless Adults Age >50 Years, Oakland, California, United States, 2013–2014.

| No. (%) (n = 350) | Physical Abuse | Sexual Abuse | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Victimization before age 18 | 132 (37.8) | 116 (33.3) | 46 (13.2) |

| Caregiver | 26 (7.4) | 31 (8.9) | 7 (2) |

| Someone else | 69 (19.7) | 57 (16.3) | 32 (9.1) |

| Both | 38 (10.9) | 28 (8.0) | 7 (2.0) |

| Victimization in adulthood (after age 18) | 186 (53.3) | 178 (51.2) | 46 (13.2) |

| Intimate partner | 20 (5.7) | 26 (7.4) | 10 (2.9) |

| Someone else | 120 (34.3) | 117 (33.4) | 29 (8.3) |

| Both | 46 (13.1) | 35 (10.0) | 7 (2.0) |

Factors Associated With Recent Violent Victimization

In multivariable GEE models, participants who remained homeless at follow-up, as determined by HEARTH criteria, were more likely to experience recent violent victimization than those who became housed (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 2.01; CI: [1.41, 2.87]) (Table 3). Identifying as non-Black (vs. Black) (AOR = 1.65; CI: [1.09, 2.50]), having experienced early life victimization (AOR = 1.75; CI: [1.19, 2.58]), reporting heavy drinking (AOR = 1.68; CI: [1.10, 2.57]), reporting moderate-to-severe illicit drug use (AOR = 1.72; CI: [1.20, 2.45]), and having an ADL impairment (AOR = 1.73; CI: [1.25, 2.41]) were associated with a higher odds of recent violent victimization. Women, compared with men, had an elevated point estimate for experiencing victimization, although this did not reach statistical significance (AOR = 1.36; CI: [0.89, 2.08]).

Table 3.

Odds of Experiencing Recent Violent Victimization Over 3 Years in GEE Model Among Adults Age >50 Years Who Were Homeless at Baseline 2013–2014, Oakland, California, United States.

| OR [95% CI] | AOR [95% CI] | |

|---|---|---|

| Women | 1.36 [0.89, 2.08] | |

| Age | 0.98 [0.94, 1.02] | |

| Race (Non-Black vs. Black) | 1.86 [1.25, 2.76] | 1.65 [1.09, 2.50] |

| Victimization before age 18 | 1.87 [1.29, 2.71] | 1.75 [1.19, 2.58] |

| Homelessness (HEARTH) | 2.17 [1.54, 3.06] | 2.01 [1.41, 2.87] |

| Social support | ||

| 0 confidants (referent category) | ||

| 1–5 confidants | 0.80 [0.56, 1.16] | |

| ≥6 confidants | 0.46 [0.22, 0.94] | |

| Substance use and mental health | ||

| Heavy drinkinga | 1.92 [1.25, 2.95] | 1.68 [1.10, 2.57] |

| Moderate-to-severe illicit drug useb | 1.96 [1.38, 2.78] | 1.72 [1.20, 2.45] |

| Moderate-to-severe depressive symptomatologyc | 1.69 [1.17, 2.46] | |

| Functional status | ||

| Cognitive impairmentd | 1.12 [0.75, 1.69] | |

| ≥1 ADL impairment | 1.83 [1.33, 2.52] | 1.73 [1.25, 2.41] |

Note. GEE = generalized estimating equations; OR = unadjusted odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; AOR = adjusted odds ratio; HEARTH = Homelessness Emergency Assistance and Rapid Transitions to Housing Act; ADL = activities of daily living; CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale.

Six or more drinks on one occasion at least once monthly.

Moderate-to-severe illicit drug use past 6 months defined as a World Health Organization Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test score for either cocaine, methamphetamines, or opioids of ≥4 (range 0–39; higher scores indicate more problems).

CES-D score ≥ 22.

Cognitive impairment defined as a Modified Mini-Mental State Examination score below the 7th percentile (i.e., 1.5 SD below the demographically adjusted cohort mean).

In our secondary analysis, spending 1 to 7 nights (AOR = 2.28; CI: [0.95, 5.48]), 8 to 120 nights (AOR = 1.59; CI: [0.99, 2.54]), and 121 or more nights (AOR = 1.88; CI: [1.24, 2.85]) unsheltered, as compared with no nights, was associated with an increased likelihood of recent victimization (Appendix). All variables that were significant in the HEARTH model remained significant.

Missing Data

We conducted 350 baseline and 1,547 follow-up interviews. Seven participants died between the baseline and first follow-up interview. Of the 343 participants who survived to the first follow-up interview, 91.0% had at least one follow-up visit. The completion rate for each follow-up interview ranged from 74.9% to 81.0%. There were no missing data for sex, race, age, and HEARTH.

The independent variables in the multivariable model had between 0.1% and 4% missing data. Using complete case analysis, we excluded 1.4% of observations due to one or more missing variables in our primary model (using HEARTH criteria) and 5.0% in our secondary analysis (using number of nights spent unsheltered or in emergency shelters). The difference in the AORs for homelessness (based on HEARTH criteria) between those with complete (AOR = 1.70; CI: [1.11, 2.59]) versus incomplete (AOR = 2.01; CI: [1.41, 2.87]) follow-up had overlapping CIs.

Discussion

In a population-based cohort of older adults who were homeless at baseline, we found rates of violent victimization more than 10 times higher than experienced by older adults in the general population (Acierno et al., 2010; Truman & Morgan, 2018). Participants who had persistent homelessness experienced twice the odds of victimization compared with those who regained housing, after adjusting for known risk factors. This finding was robust across different measures of homelessness. These results support our hypothesis that older homeless adults have an elevated risk of violent victimization and that the dangerous environment of homelessness contributes to the excess risk. Our findings suggest that housing may reduce this risk.

People experiencing homelessness lack choice in their environment, lack environmental controls that increase safety, and stay in crowded spaces in close contact with individuals who may have increased impulsivity and tendency toward violence (Kushel et al., 2003). Crowding may increase stress levels and disputes that lead to violence. Stigma and dehumanizing language used to describe people experiencing homelessness may leave them vulnerable to attacks by bystanders. Due to past negative interactions, concerns regarding racial bias, the criminalization of behaviors associated with homelessness, and having prior criminal justice histories, people who are homeless may avoid contacting police when threatened (Garland, Richards, & Cooney, 2010; Zakrison, Hamel, & Hwang, 2004).

Over 10% of our study participants reported physical victimization in the past 6 months at baseline, compared with 1.6% of older adults in the general population reporting physical victimization in the past year (Acierno et al., 2010). The discrepancy in sexual victimization was even higher, despite the fact that three quarters of study participants were men, who are less likely to experience sexual victimization (Acierno et al., 2010). While in the general population, rates of violent victimization decrease with age (Truman & Morgan, 2018), we found rates similar to that found in studies of homeless adults younger than 50 (Riley et al., 2014; Roy, Crocker, Nicholls, Latimer, & Ayllon, 2014; Tsai, Weiser, Dilworth, Shumway, & Riley, 2015).

The lower rates experienced by older individuals are thought to be due to their decreased likelihood of encountering “motivated offenders” and of being in environments that lack protections, either physical barriers or people who intervene and protect against violence (Cohen & Felson, 1979). In the general population, the lower probability of these factors may outweigh the increased likelihood that people target older adults because of their perceived vulnerability due to frailty and inability to self-defend. Our findings suggest that homeless older adults lose the environmental protections experienced by older adults in the general community.

We found that functional impairment was associated with victimization. In the general population, functional impairment is associated with victimization; however, the direction and significance of this association varies by study population and measures of victimization (Rosen et al., 2016; Williams et al., 2017). Our findings support our hypothesis that, in homeless populations, those with functional impairment would be a higher risk of victimization due to inability to self-defend while living in dangerous environments.

We found an association between early life victimization, heavy drinking, and illicit drug use with recent victimization, all known risk factors for victimization. These factors are more common in homeless, compared with non-homeless, populations and account for some of the increased risk. Addressing these risk factors could help reduce the risk of victimization.

In our sample, of which approximately 80% of participants identify as Black, those who were non-Black had higher odds of victimization. Black Americans are at 3 to 4 times increased risk of homelessness, compared with non-Black populations (Henry, Watt, Rosenthal, Shivji, & Abt Associates, 2017). This increased risk is thought to be due to structural risk factors, including discrimination in housing, education, employment, and criminal justice systems (Olivet et al., 2018). Thus, Black Americans who are homeless may have fewer individual risk factors for victimization. These differences may represent unmeasured confounders in our analysis. This may account for the lower odds of victimization among Black participants in this study.

This study has several limitations. Within each 6-month interval, we do not know the temporal association with victimization and housing. It is possible that having a recent exposure to victimization limited individuals’ ability to regain housing. While we had high follow-up rates, it is possible that missed visits may have been informative. For instance, if victimization led to injuries that caused individuals to miss visits, our estimates would underestimate the true rate. Our sensitivity analysis indicates that our estimate of the association between homelessness and victimization was conservative. We did not assess whether there were differential risks among homeless individuals living in unsheltered versus sheltered environments. Examining the health-related sequelae of victimization is beyond the scope of this study. Furthermore, we did not collect data on whether the offender, when specified as someone other than an intimate partner, was a stranger or known to the participant. We did not find a significant association between gender and victimization. This may be due to a lack of statistical power in our study sample, due to the low proportion of women among older homeless adults. These are topics for future research.

With the aging of the homeless population and the likelihood that older adults face even greater health consequences from violent victimization, there is an urgent need to intervene to prevent victimization. Health care providers caring for older homeless adults should be aware of the risks of victimization and screen for injuries and for other sequelae, including posttraumatic stress disorder. Prior studies have found multiple positive impacts of rehousing older homeless individuals (Brown et al., 2015). Our findings extend these to suggest that rehousing older adults may reduce the risk of experiencing violent victimization. The high risk of victimization of frail older adults presents another compelling motivation for housing this vulnerable population.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge our colleagues for their invaluable contributions to the HOPE HOME study. We would like to acknowledge our colleague Angela Allen, who passed away in May 2015, for her incredible contributions to the study. The authors also thank the staff at St. Mary’s Center and the HOPE HOME Community Advisory Board for their guidance and partnership.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging (NIA) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (grant numbers K24AG046372 to M.B.K., R01AG041860 to M.B.K.) and by the UC Berkeley College of Letters & Sciences (Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship to M.S.T.). These funding sources had no role in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Author Biographies

Michelle S. Tong, BA, is a medical student at the University of California, San Francisco. Her research interests are in social epidemiology and the structural determinants of health and homelessness. She is interested in using policy research to inform public-private sector interventions and local systemic change.

Lauren M. Kaplan, PhD, is a technical writer at the University of California, San Francisco. She earned her doctorate in Sociology at the Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität Frankfurt am Main, Germany. Her research focuses on homelessness and aging, HIV, intimate partner violence, and childhood victimization.

David Guzman, MSPH, is a biostatistician at the University of California, San Francisco. He is the statistician for the HOPE HOME project. His primary areas of interest are homelessness, aging, chronic disease prevention, and HIV. He received his MS from the Department of Epidemiology at Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia.

Claudia Ponath, MA, is a project director at the University of California, San Francisco. She works with Dr. Kushel coordinating the HOPE HOME study. Her primary research interests are vulnerable populations, homelessness, substance abuse, and HIV.

Margot B. Kushel, MD, is a professor of Medicine at the University of California, San Francisco and Director of the UCSF Center for Vulnerable Populations at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital and Trauma Center. Her research focuses on reducing the burden of homelessness and housing instability on health, especially in older adults and medically complicated individuals.

Appendix

Appendix.

Sensitivity Analysis Using Residential Calendar Nights Spent Unsheltered: Odds of Experiencing Recent Violent Victimization.

| Unadjusted OR [95% CI] | AOR [95% CI] | |

|---|---|---|

| Women | 1.36 [0.89, 2.08] | — |

| Age | 0.98 [0.94, 1.02] | — |

| Race (Non-Black vs. Black) | 1.86 [1.25, 2.76] | 1.07 [1.07, 2.45] |

| Victimization before age 18 | 1.87 [1.29, 2.71] | 1.67 [1.13, 2.47] |

| Nights spent in unsheltered settings or emergency shelter, past 6 months | ||

| 0 | — | — |

| 1–7 | 2.50 [1.07, 5.82] | 2.28 [0.95, 5.48] |

| 8–120 | 1.78 [1.13, 2.81] | 1.59 [0.99, 2.54] |

| ≥121 | 2.15 [1.44, 3.20] | 1.88 [1.24, 2.85] |

| Social support | ||

| 0 confidants (referent category) | — | — |

| 1–5 confidants | 0.80 [0.56, 1.16] | — |

| ≥6 confidants | 0.46 [0.22, 0.94] | — |

| Substance use and mental health | ||

| Heavy drinkinga | 1.92 [1.25, 2.95] | 1.66 [1.07, 2.56] |

| Moderate-to-severe illicit drug useb | 1.96 [1.38, 2.78] | 1.74 [1.21, 2.50] |

| Moderate-to-severe depressive symptomatologyc | 1.69 [1.17, 2.46] | — |

| Functional status | ||

| Cognitive impairmentd | 1.12 [0.75, 1.69] | — |

| ≥1 ADL impairment | 1.83 [1.33, 2.52] | 1.73 [1.24, 2.43] |

Note. OR = unadjusted odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; AOR = adjusted odds ratio; ADL = activities of daily living; CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale.

Six or more drinks on one occasion at least once monthly.

Moderate-to-severe illicit drug use past 6 months defined as a World Health Organization Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test score for cocaine, methamphetamines, or opioids of ≥4 (range 0–39; higher scores indicate more problems).

CES-D score ≥22.

Cognitive impairment defined as a Modified Mini-Mental State Examination score below the 7th percentile (i.e., 1.5 SD below the demographically adjusted cohort mean).

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Acierno R, Hernandez MA, Amstadter AB, Resnick HS, Steve K, Muzzy W, & Kilpatrick DG (2010). Prevalence and correlates of emotional, physical, sexual, and financial abuse and potential neglect in the United States: The national elder mistreatment study. American Journal of Public Health, 100, 292–297. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.163089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arata CM (2006). Child sexual abuse and sexual revictimization. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 9, 135–164. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.9.2.135 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, & Monteiro MG (2001). The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for use in primary care. Retrieved from https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/67205/WHO_MSD_MSB_01.6a.pdf; jsessionid=4B6A21C48E4AC76E20296ECE21914ECA?sequence=1

- Bravo G, & Hebert R (1997). Age- and education-specific reference values for the mini-mental and modified mini-mental state examinations derived from a non-demented elderly population. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 12, 1008–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RT, Goodman L, Guzman D, Tieu L, Ponath C, & Kushel MB (2016). Pathways to homelessness among older homeless adults: Results from the HOPE HOME Study. PLoS ONE, 11(5), e0155065. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RT, Hemati K, Riley ED, Lee CT, Ponath C, Tieu L, … Kushel MB (2017). Geriatric conditions in a population-based sample of older homeless adults. The Gerontologist, 57, 757–766. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RT, Kiely DK, Bharel M, & Mitchell SL (2012). Geriatric syndromes in older homeless adults. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 27, 16–22. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1848-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RT, Miao Y, Mitchell SL, Bharel M, Patel M, Ard KL, … Steinman MA (2015). Health outcomes of obtaining housing among older homeless adults. American Journal of Public Health, 105, 1482–1488. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen RC, Hodgkins CC, Garces LK, Estlund KL, Miller MD, & Touchton R (2005). Homeless, mentally ill and addicted: The need for abuse and trauma services. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 16, 615–622. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2005.0091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen LE, & Felson M (1979). Social change and crime rate trends: A routine activity approach. American Sociological Review, 44, 588–608. doi: 10.2307/2094589 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Culatta E, Clay-Warner J, Boyle KM, & Oshri A (2017). Sexual Revictimization: A Routine Activity Theory Explanation. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1177/0886260517704962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DePrince AP (2005). Social cognition and revictimization risk. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 6, 125–141. doi: 10.1300/J229v06n01_08 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias A, Sales L, Mooren T, Mota-Cardoso R, & Kleber R (2017). Child maltreatment, revictimization and post-traumatic stress disorder among adults in a community sample. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 17, 97–106. doi: 10.1016/j.ijchp.2017.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz TL, & Wright JD (2008). Age and gender differences and predictors of victimization of the older homeless. Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect, 17, 37–60. doi: 10.1300/J084v17n01_03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn LB, & Jeste DV (2001). Enhancing informed consent for research and treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology, 24, 595–607. doi: 10.1016/s0893-133x(00)00218-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang B, & Yan E (2017). Abuse of Older Persons With Cognitive and Physical Impairments: Comparing Percentages Across Informants and Operational Definitions. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1177/0886260517742150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland TS, Richards T, & Cooney M (2010). Victims hidden in plain sight: The reality of victimization among the homeless. Criminal Justice Studies, 23, 285–301. doi: 10.1080/1478601X.2010.516525 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gielen AC, McDonnell KA, Wu AW, O’Campo P, & Faden R (2001). Quality of life among women living with HIV: The importance violence, social support, and self care behaviors. Social Science & Medicine, 52, 315–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gielen AC, O’Campo PJ, Faden RR, Kass NE, & Xue X (1994). Interpersonal conflict and physical violence during the childbearing year. Social Science & Medicine, 39, 781–787. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90039-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry M, Watt R, Rosenthal L, & Shivji A Abt Associates. (2017). The 2017 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to congress. Retrieved from https://files.hudexchange.info/resources/documents/2017-AHAR-Part-1.pdf

- Homeless Emergency Assistance and Rapid Transition to Housing Act of 2009. Definition of homelessness, U.S. Congress; (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Humeniuk R, Henry-Edwards S, Ali R, Poznyak V, & Monteiro M (2010). The Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST): Manual for use in primary care. Retrieved from https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44320/9789241599382_eng.pdf?sequence=1

- Hwang SW, Kirst MJ, Chiu S, Tolomiczenko G, Kiss A, Cowan L, & Levinson W (2009). Multidimensional social support and the health of homeless individuals. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 86, 791–803. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9388-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judges RA, Gallant SN, Yang L, & Lee K (2017). The role of cognition, personality, and trust in fraud victimization in older adults. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, Article 588. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz S (1983). Assessing self-maintenance: Activities of daily living, mobility, and instrumental activities of daily living. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 31, 721–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushel MB, Evans JL, Perry S, Robertson MJ, & Moss AR (2003). No door to lock: Victimization among homeless and marginally housed persons. Archives of Internal Medicine, 163, 2492–2499. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.20.2492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CT, Guzman D, Ponath C, Tieu L, Riley E, & Kushel M (2016). Residential patterns in older homeless adults: Results of a cluster analysis. Social Science & Medicine, 153, 131–140. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery AE, Cutuli JJ, Evans-Chase M, Treglia D, & Culhane DP (2013). Relationship among adverse childhood experiences, history of active military service, and adult outcomes: homelessness, mental health, and physical health. American Journal of Public Health, 103(Suppl. 2), S262–S268. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan R, & Kena G (2018). Criminal victimization, 2016. Retrieved from https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/cv16re.pdf

- Olivet J, Dones M, Richard M, Wilkey C, Yapolskaya S, Beit-Arie M, & Joseph L (2018). Phase one study findings. Center for Social Innovation. Supporting Partnerships for Anti-Racist Communities. Retrieved from https://center4si.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/SPARC-Phase-1-Findings-March-2018.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Parsell C, Tomaszewski W, & Phillips R (2014). Exiting unsheltered homelessness and sustaining housing: A human agency perspective. Social Service Review, 88, 295–321. doi: 10.1086/676318 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Poole C, & Rietschlin J (2012). Intimate partner victimization among adults aged 60 and older: An analysis of the 1999 and 2004 General Social Survey. Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect, 24, 120–137. doi: 10.1080/08946566.2011.646503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley ED, Cohen J, Knight KR, Decker A, Marson K, & Shumway M (2014). Recent violence in a community-based sample of homeless and unstably housed women with high levels of psychiatric comorbidity. American Journal of Public Health, 104, 1657–1663. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen T, Clark S, Bloemen EM, Mulcare MR, Stern ME, Hall JE, … Eachempati SR (2016). Geriatric assault victims treated at U.S. trauma centers: Five-year analysis of the national trauma data bank. Injury, 47, 2671–2678. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2016.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy L, Crocker AG, Nicholls TL, Latimer EA, & Ayllon AR (2014). Criminal behavior and victimization among homeless individuals with severe mental illness: A systematic review. Psychiatric Services, 65, 739–750. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver E (2006). Mental disorder and violent victimization: The mediating role of involvement in conflicted social relationships. Criminology, 40, 191–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9125.2002.tb00954.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spinelli MA, Ponath C, Tieu L, Hurstak EE, Guzman D, & Kushel M (2017). Factors associated with substance use in older homeless adults: Results from the HOPE HOME study. Substance Abuse, 38, 88–94. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2016.1264534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy SUE, & Sugarman DB (1996). The Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues, 17, 283–316. doi: 10.1177/019251396017003001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Truman J, & Morgan R (2018). Criminal victimization, 2015. Retrieved from https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/cv15.pdf

- Tsai AC, Weiser SD, Dilworth SE, Shumway M, & Riley ED (2015). Violent victimization, mental health, and service utilization outcomes in a cohort of homeless and unstably housed women living with or at risk of becoming infected with HIV. American Journal of Epidemiology, 181, 817–826. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwu350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsemberis S, McHugo G, Williams V, Hanrahan P, & Stefancic A (2006). Measuring homelessness and residential stability: The residential time-line follow-back inventory. Journal of Community Psychology, 35, 29–42. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20132 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel SL, Leake BD, & Gelberg L (2000). Health of homeless women with recent experience of rape. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 15, 265–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2000.04269.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel SL, Tucker JS, Elliott MN, Marshall GN, & Williamson SL (2004). Physical violence against impoverished women: A longitudinal analysis of risk and protective factors. Women’s Health Issues, 14, 144–154. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2004.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JL, Racette EH, Hernandez-Tejada MA, & Acierno R (2017). Prevalence of Elder Polyvictimization in the United States: Data From the National Elder Mistreatment Study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. doi: 10.1177/0886260517715604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong Y-LI (2000). Measurement properties of the center for epidemiologic studies—Depression Scale in a homeless population. Psychological Assessment, 12, 69–76. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.12.1.69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakrison TL, Hamel PA, & Hwang SW (2004). Homeless people’s trust and interactions with police and paramedics. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 81, 596–605. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jth143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]