Abstract

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Professional identity formation (PIF) involves internalizing and demonstrating the behavioral norms, standards, and values of a professional community, such that one comes to “think, act and feel” like a member of that community. Professional identity influences how a professional perceives, explains, presents and conducts themselves. This report of the 2020-2021 AACP Student Affairs Standing Committee (SAC) describes the benefits of a strong professional identity, including its importance in advancing practice transformation. Responding to a recommendation from the 2019-2020 SAC, this report presents an illustrative and interpretative schema as an initial step towards describing a pharmacist’s identity. However, the profession must further elucidate a universal and distinctive pharmacist identity, in order to better support pharmacists and learners in explaining and presenting the pharmacist’s scope of practice and opportunities for practice change. Additionally, the report outlines recommendations for integrating intentional professional identity formation within professional curricula at colleges and schools of pharmacy. Although there is no standardized, single way to facilitate PIF in students, the report explores possibilities for meeting the student support and faculty development needs of an emerging new emphasis on PIF within the Academy.

Keywords: professional identity formation, practice transformation, professionalism

INTRODUCTION

Colleges and schools of pharmacy play a critical role in professional identity formation (PIF) through design of courses and experiential education, as well as co-curricular requirements. Through the policies on professional education for the American Association of College of Pharmacy (AACP) colleges and schools are encouraged “to advance education that is aimed at the intentional formation of professional identity (ie, thinking, feeling and acting like a pharmacist) and developed and implemented in cooperation with the professional pharmacy organizations within the broader pharmacy profession.”1 This committee report expands on the work of the 2019-2020 AACP Student Affairs Committee by describing the benefits of a strong professional identity, the challenges of a universal pharmacist identity, and the importance of identity to practice transformation. It presents an illustrative and interpretative schema as an initial step towards describing a pharmacist’s identity. It also explores the faculty development and student support needed to engage in intentional formation of professional identity and implementation activities for colleges and schools to optimally engage in PIF.2

COMMITTEE CHARGES AND HISTORY

President Anne Lin formed the 2020-2021 Student Affairs Standing Committee (SAC) to continue the work of the 2019-2020 SAC on professional identity formation (PIF). With a year of research and discussion, some returning members and some new members, the 2020-2021 committee was uniquely positioned to dig deeper into the issues and advance the former committee’s plans and recommendations. The charges were to examine: 1) strategies to support PIF in our educational systems, 2) the use of implementation science to support the advancement of PIF and 3) PIF-supportive activities for the new Center to Accelerate Pharmacy Practice Transformation and Academic Innovation (the Center). To address the charges, members of the committee discussed the work of the preceding SAC in context of the other 2019-2020 AACP standing committees, analyzed the documents of multiple pharmacy professional organizations that describe aspects of a pharmacist’s professional identity, and reviewed the literature for approaches to develop student pharmacists’ professional identity. The SAC began by organizing around two goals established by the 2019-2020 SAC: 1) Develop a framework of essential values that describe the professional identity of a pharmacist and 2) Integrate PIF in pharmacy education, training, and practice. Biweekly meetings were scheduled online for either the entire committee or two subgroups that each focused on one of the goals. The SAC also met with members of the 2020-2021 Research and Graduate Affairs Standing Committee to better understand the use of implementation science to promote PIF in Doctor of Pharmacy (Pharm.D.) degree programs.

Concurrent with its investigations and deliberations on the charges, and in response to a recommendation in the previous report related to faculty development and programming (Recommendation 3),2 the 2020-2021 SAC worked with AACP to develop an 2021 Interim Meeting session, “What’s the end goal? Professionalism or professional identity?” with Dr. Yvonne Steinert, Professor of Family Medicine and Health Sciences Education at McGill University.3 The programming followed on the PIF microsessions during the 2020 AACP Interim Meeting, a PIF webinar by 2019-2020 SAC members in May 2020, and PIF posters at the 2020 AACP Annual Meeting. The 2020-2021 SAC has also been advocating for the inclusion of PIF in the 2021-2024 AACP Strategic Plan.

In brief, professional identity involves internalizing and demonstrating the behavioral norms, standards, and values of a professional community, such that one comes to “think, act and feel” like a member of that community.4-6 PIF extends affective development beyond the professionalism competencies well-known to pharmacy educators. It begins when novices first learn the foundational knowledge of the profession and observe the actions of members of the professional community they are joining. PIF continues when students practice acting like a member of the profession, doing the work of the profession under the observation and guidance of mentors, and getting feedback on actions, attitudes, and behaviors related to professional norms. By regularly demonstrating competence in the roles and responsibilities of the profession and sufficient consistency in conforming to the professional expectations of colleagues, the individual begins to feel like a member of the community and an initial professional identity is developed. The PIF process continues indefinitely over the course of years, with identity evolving in response to additional experiences as a working member of the professional community.5

Following our review of the literature and discussions with experts, we contend that professional identity is too important to leave to chance. While there is not one definitive path to identity, or a narrow set of activities or experiences that guarantee it, pharmacy educators must nonetheless continue to collaborate in learning more about effective PIF approaches and incorporating those approaches into the curriculum and co-curriculum in a systematic, progressive manner. The benefits of a strong professional identity are significant. Identity influences how a professional perceives, explains, presents and conducts themselves.7 Identity is also a key determinant of the scope and nature of an individual’s work and prioritization of their roles.8 As such, a strong professional identity is needed in this era of practice transformation and expansion of the pharmacist’s roles. Furthermore, learners require guidance in developing a professional identity while also navigating amongst multiple emerging identities. Student pharmacists are moving from peripheral participant (ie, novice) to full member of the profession by gaining competency, yes, but also by learning the language, the hierarchies within the healthcare system, and the methods to manage the ambiguity that is inherent in patient care.5 Pharmacy educators have the opportunity to extend our work with professionalism into the identity domain by making PIF an educational goal, engaging students in the work of identity formation and explicitly attending to important factors impacting PIF, including role modelling, mentoring, experiential learning, guided reflection and a welcoming community of practice.7 Pharmacy educators are important in helping learners to navigate transitions, integrate personal and professional identities, manage emotions associated with this development (eg, anxiety, frustration, satisfaction) and learning to “play the role” on their way to being a pharmacist.5

PHARMACIST ROLES AS A COMPONENT OF IDENTITY

As described by Cruess and Cruess, “It has long been known that humans pass through recognizable developmental stages throughout their lives, during which their unique identity or identities are strongly linked to the roles that they play.”7 Therefore, in considering identity, it is important to understand the roles that pharmacists have and are playing. Urick and Meggs summarize the evolution of community pharmacy practice, arguably the face of the profession to the public, by dividing it up into four eras based on the pharmacist’s primary role and/or responsibility.9 In the “Soda Fountain Era” from 1920-1949, there was a transition away from the pharmacist’s traditional role of compounding medications toward dispensing manufactured proprietary medications. This led to the second era of “Lick, Stick, Pour, and More,” from 1950-1979. During this era, individual pharmacy practitioners and advocacy groups began to promote the idea that the primary role of the pharmacist was to educate the patient about their medications, a concept rapidly adopted by state pharmacy practice acts and emphasized in pharmacy curricula. The “Pharmaceutical Care Era” between 1980-2009 saw major changes to pharmacy practice requiring advanced education, such as expansion of medication administration and medication therapy management; thus, the Doctor of Pharmacy became the sole degree program for pharmacists. In the present “Post-Pharmaceutical Care Era,” acute and ambulatory care practice have largely evolved into the role of clinical services provider. However, much of community pharmacy practice continues to straddle the roles of the “Lick, Stick, Pour and More” and “Pharmaceutical Care” eras. As stated by Cruess, Cruess, and Steinert, “With time, the role comes to represent the individual’s identity or identities.”6

Observing differing roles of the pharmacist, such as a care provider in some settings and product dispenser in other settings, can create confusion, frustration and/or stress for pharmacy students as they navigate the tension between ‘who they are’ and ‘who they wish to become.’ Understandably, the various roles may seem discordant or even incompatible with each other. However, professional identity involves more than just the tasks and functions associated with one’s job. In assuming a professional identity, students are also internalizing the value systems of the profession and its norms.7 Pharmacy educators are critical in providing guided reflection and mentorship to help students think beyond their observations of pharmacist roles and differences between settings. By clarifying the distinctions between roles and the other elements of identity, students will see that regardless of the practice site, pharmacists share a common community of practice based on a fundamental core set of values, characteristics and norms. In addition, schools and colleges can facilitate ‘who students wish to become’ by offering early career guidance and personalized education. Offering students curricular and co-curricular opportunities that examine emerging career opportunities will help them to see a pharmacist’s identity as including being a change agent in healthcare.10

THE CHALLENGES OF A UNIVERSAL PHARMACIST IDENTITY

There is evidence of five identity discourses in pharmacy, including apothecary, dispenser, merchandiser, expert advisor and healthcare provider. Rather than shifting over time, newer identities have been added to existing ones resulting in a “pile up.”11 Elvey, Hassell and Hall’s research indicates nine role-based identities for pharmacists, including the scientist, clinical practitioner, medicines supplier and business person.12 As a result, the 2019-2020 SAC report recommended that “AACP should initiate conversations within the profession of pharmacy to develop a unified identity” (Recommendation 2).2

Not only do identities differ among practitioners, lack of an agreed-upon identity is evident in stakeholder opinion on the content of educational programming. For example, a study examining European community pharmacists’ and pharmacy academics’ views on pharmacy practice competencies found that academics emphasized the importance of research, pharmaceutical technology, and the regulatory aspects of quality, while community pharmacists concentrated more on patient care competencies.13 Similarly, Nobel et al. reported that students noticed a disconnect between learning in the curriculum and observations during experiential learning. For example, they were taught by professors that pharmacists are more than dispensing agents for physicians, yet were told by many preceptors that being patient-focused was not efficient in community pharmacy. This dissonance slowed professional identity formation in these students due to a lack of reinforcement of theoretical and practical components.14

A Step Toward Describing A Universal Pharmacist’s Identity

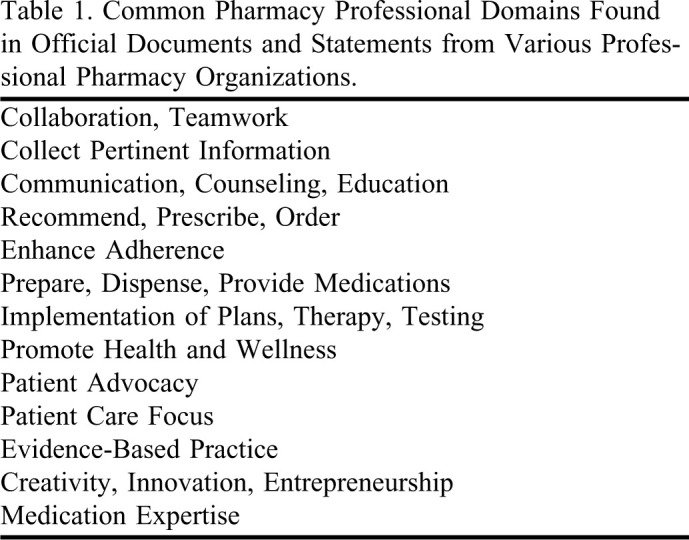

Professional organizations in pharmacy have identified the attributes of member pharmacists and represent these identities in official papers and statements by the organizations. Analysis of those official papers and statements was undertaken as a step toward defining a pharmacist’s professional identity. A subgroup of the SAC searched the websites of the 13 member organizations of the Joint Commission of Pharmacy Practitioners (JCPP) to identify official papers or statements providing descriptions or definitions of member pharmacist attributes, roles and responsibilities. A total of 21 white papers, position statements, and other sources were identified for review. These materials included the American Pharmacists Association (APhA) Oath of a Pharmacist,15 the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) statements on Professionalism and the Pharmacist’s Role in Primary Care,16,17 the Center for the Advancement of Pharmacy Education (CAPE) Educational Outcomes,18 the JCPP Pharmacists’ Patient Care Process,19 and the National Association of Boards of Pharmacy (NABP) Model State Pharmacy Act and Model Rules,20 among others.21-35 Two-thirds of the sources reviewed either originated or were revised within the past 10 years. Sources were reviewed for descriptions of how pharmacists think, act, and feel. A total of 211 descriptors were identified (51 for Think, 143 for Act, and 17 for Feel) and were categorized into 23 areas, which were then summarized into 13 domains (Table 1).

Table 1.

Common Pharmacy Professional Domains Found in Official Documents and Statements from Various Professional Pharmacy Organizations.

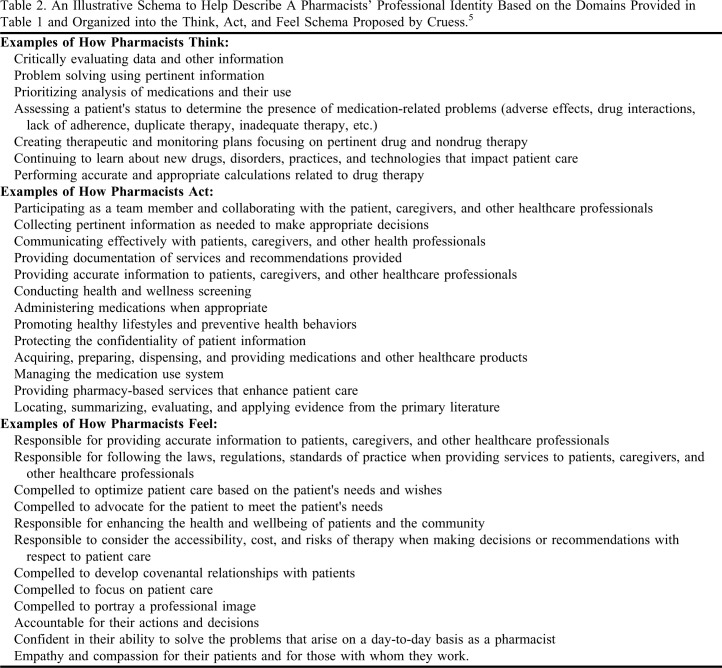

The domains (Table 1) were then discussed with the entire SAC to develop professional identity items that would fit into Think, Act, and Feel (Table 2), which is a schema suggested by Cruess et al. in their discussion of identity.4 While these items were not taken verbatim from the 21 sources, they were derived from discussing the various points raised across the sources. This schema can be used as a guide for pharmacy learners, educators, and practitioners in considering the identity of a pharmacist. The examples related to feeling like a pharmacist were most difficult to identify and elucidate, and more work is needed in this area.

Table 2.

An Illustrative Schema to Help Describe A Pharmacists’ Professional Identity Based on the Domains Provided in Table 1 and Organized into the Think, Act, and Feel Schema Proposed by Cruess.5

While this schema provides some initial insight, there is still a need for further description of the professional identity of a pharmacist. As part of this clarification, the profession should consider moving beyond roles, traits, characteristics and attributes. Descriptions of the profession’s values, standards and norms that take into account current and future practice would complement the work presented in Tables 1 and 2 by elaborating on the principles guiding behavior, especially in navigating difficult or ambiguous situations in the increasing complexity of practice.

Distinguishing a Pharmacist’s Identity from Other Healthcare Professionals

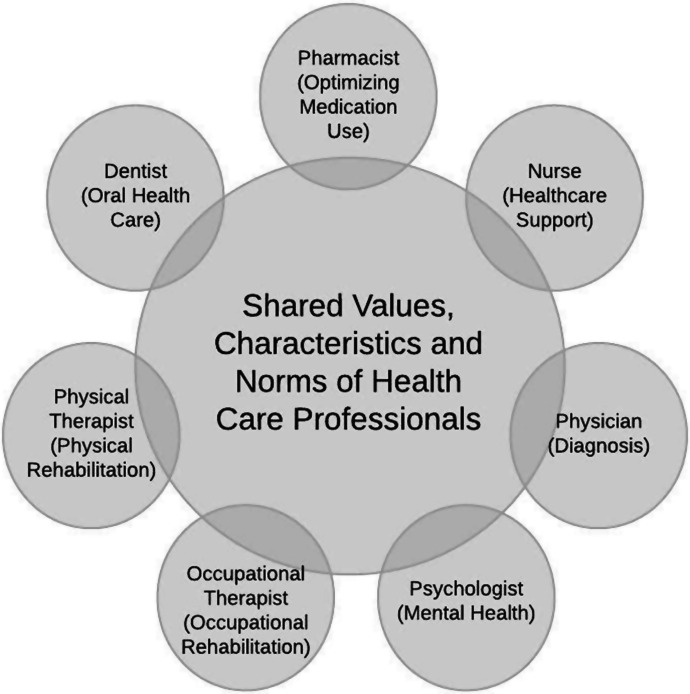

Any work in describing the pharmacist’s identity cannot ignore the identities of other healthcare professionals. According to Merriam Webster, the definition of identity is “the distinguishing character or personality of an individual.”36 What distinguishes pharmacists from other healthcare professionals and leads to acceptance of their value to patient care? While profession-specific roles and tasks may be easily distinguishable, how one thinks, acts, and feels as a professional is to some extent shared among healthcare professionals. For example, compassion, empathy, communication skills, and the ability to think critically, utilize sound judgment to solve problems, make evidence-based decisions, and defend a point of view are arguably traits that comprise professional identity for all healthcare professions. One might conclude there is a foundational shared identity of a healthcare professional to which the identities of a specific profession are added. Figure 1 provides an illustration of only a few examples of many healthcare professions sharing common values, characteristics and norms.

Figure 1.

Common and Distinctive Values, Characteristics and Norms of Healthcare Professionals.

Given the assertion of a shared identity among healthcare professionals, Tables 1 and 2 can be interpreted in a new way. Most of the elements listed could be considered as representing any healthcare professional. It is the pharmacists’ role in optimizing medication use that distinguishes our profession from others. Pharmacists are uniquely trained to identify medication therapy problems. No other profession teaches medication-related skills, such as comprehensive medication review and clinical pharmacokinetics to the degree emphasized in pharmacy education. Furthermore, colleges and schools are working to prepare students to use a consistent thought process that involves assessing each drug for indication, effectiveness, safety and adherence.37 Additional work in elucidating the distinctiveness of the pharmacist’s identity is needed to support pharmacists and learners in explaining, presenting and conducting themselves in a manner that positively affects practice transformation.

Complicating the discussion is that values and norms are further stratified and nuanced among different types of roles and settings, making it more challenging to determine one universal professional identity for pharmacists. For example, while it may be the norm for clinic-based, ambulatory care pharmacists to follow up with patients to determine the effectiveness of therapy, this may not be the norm in another practice setting. Additionally, norms also vary by region within the United States and globally. For example, the pharmacist functions permitted by law may differ in California compared with New York, which may impact professional identity. Clearly, discussion is needed within the profession to determine the universal and distinctive norms and core values common to all pharmacist professionals.

IDENTITY AND PRACTICE TRANSFORMATION

In order to fully capitalize on the current and future abilities of pharmacists to meet societal needs and expectations, practice transformation within the pharmacy profession needs to be unified and accelerated. Perceptions of the scope and nature of a professional’s work and prioritization of the professional’s roles is influenced by professional identity.8 This conceptualization of “being a pharmacist,” in turn, influences how the professional perceives, explains, presents and conducts themselves,7 which in turn influences their approach when engaging in practice advancement and transformation.

To support the profession, a universal professional identity is needed that would be readily recognized by patients, caregivers, other healthcare professionals, payers, governmental and private industry entities, and other stakeholders in healthcare. A universal professional identity should unify pharmacists by focusing on a set of common attributes, values, and norms that contribute to the delivery of high-quality pharmaceutical care, products, and services that are needed to fulfill the Quadruple Aim.38

Similar to medicine, pharmacy does not consist of just one community of practice. Physicians can demonstrate a multiplicity of professional identities as they join various communities (eg, clinical care, academia, research) with their global identity linked to their profession (medicine).39 A “landscape of communities” has been forming within pharmacy with each community developing their own unique identities.40 Practice expansion without a global identity has led to fragmentation within pharmacy, where the focus is more on the roles and attributes of pharmacists within the various communities, rather than a shared set of values and norms. This fragmentation and lack of shared professional identity has hindered a unified approach to practice transformation. The development of a universal professional identity is only possible when pharmacists embody the professional identity through their own professional identity formation, which begins in their Doctor of Pharmacy program and extends through further education, training, and practice. AACP and the Center can play a key role in establishing the shared professional identity for pharmacists and supporting colleges and schools in promoting and enhancing professional identity formation by learners, educators, and practitioners.

SUPPORTING PROFESSIONAL IDENTITY FORMATION

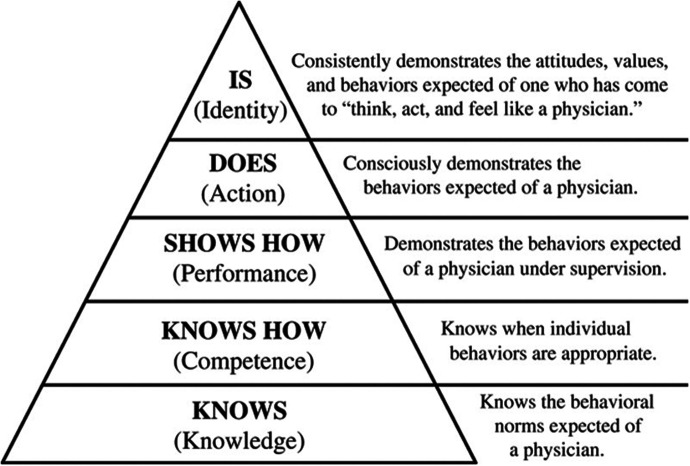

PIF has become an important consideration in health profession education programs, most notably in medicine, nursing, and now pharmacy. Foundationally to the trend, faculty must agree that formation of professional identity and demonstration of professionalism are not the same. In 2000, the American Pharmaceutical Association Academy of Student Pharmacists (APhA-ASP) and the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy Council of Deans Task Force (AACP-COD) defined professionalism as “active demonstration of traits of a professional.”41 Professionalism is described in the 2013 CAPE Outcomes as the ability to “Exhibit behaviors and values that are consistent with the trust given to the profession by patients, other healthcare providers, and society.”18 The 2014 AACP-COD Task Force on Professional Identity Formation later moved beyond demonstration of professionalism to adopt a definition of PIF: “Professional Identity Formation (PIF) is the transformative process of identifying and internalizing the ways of being and relating within a professional role.” 42

To illustrate the extension of PIF from professionalism, it is useful to imagine the addition of a new level atop Miller’s Pyramid of Professional Competence (Figure 2) as proposed by Cruess, et al.6 This imagery more easily allows educators to envision the distinction between a student who can reliably “exhibit behaviors,” which demonstrate professionalism in an advanced pharmacy practice experience (APPE) or objective structured clinical exam (ie, checking all the boxes), and a student who has truly “internalized” and relates to a professional role. This internalized identity includes professionalism, but extends to include other beliefs, values, motives, core knowledge and skills, attitudes, behaviors, and other attributes that students develop over time as they move from a nonprofessional lay person to a professional.43-45

Figure 2.

The amended version of Miller?s Pyramid of Clinical Competence. Reprinted with permission from Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc.6

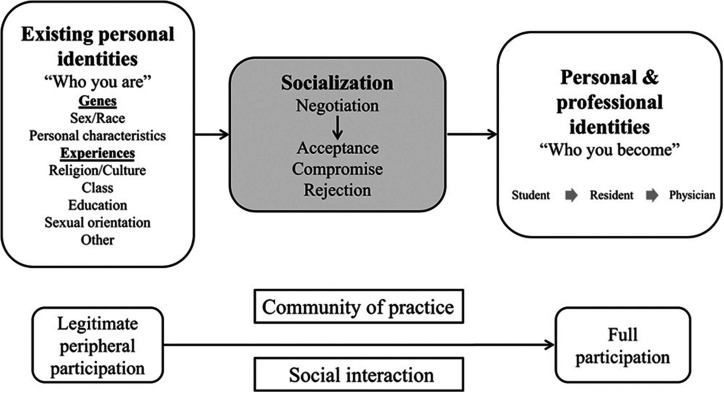

There are a number of theories describing the development of professional identity, including Self-Authorship Theory,46 Provisional Selves Theory,44 and the Theory of Social Learning, more commonly known as “Communities of Practice.”40 These example theories describe similar supports for development of the identity, including exposure to role models, active participation and imitation, and immersion. These identified supports naturally suggest pedagogical strategies faculty could use to assist students in PIF, including experiential education, guided reflection, symbolic and ceremonial events, and strong mentoring programs. Each of the aforementioned identity theories has been explored more deliberately in terms of personal identity than professional identity, though there are increasing reports of application of these theories to pharmacy education.14

Pharmacy educators are encouraged to develop a working knowledge of one or more identity theories to assist in selecting pedagogies and approaches for PIF support that align with their curricula. In particular, the role of socialization has been described as a critical factor by which an individual learns to function in a particular society.5,7 This model may be particularly helpful in assisting student services personnel, faculty and preceptors in understanding the process of identity formation (Figure 3). Factors that influence socialization include self-assessment, the learning environment, attitudes and treatment of the student by patients, peers and health professionals, as well as conscious reflection and unconscious acquisition of norms and values from experiences, role models and mentors.5

Figure 3.

A schematic representation of professional identity formation. Reprinted with permission from Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc.5

It has been argued that, if PIF is an educational goal, it must be explicitly included in the formal curriculum as part of the cognitive base of the professional.7 To that end, the SAC encourages faculty and institutions to prioritize the development of curricular, extracurricular, and co-curricular opportunities for students to explore professional identity. PIF initiatives can find a fit within a nearly endless array of possibilities from orientation day to graduation. Activities used and reported in pharmacy education have been summarized,47 including the effects of autonomy-supportive teaching in a PIF workshop series integrated into existing courses48 and embedded PIF-oriented activities in an APPE.49 Studies have also been conducted on the influence of pharmacy employment50 and the overall curriculum on PIF.14 Periods of transition (eg, entry into Introductory Pharmacy Practice Experiences) present opportunities and challenges for learners, which can be viewed through the lens of identity formation.7 Pharmacy educators should be creative and flexible in development and evaluation of activities, and responsive to the ongoing global conversation about pharmacist identity in a time of practice transformation.

Self-assessment is critical in charting progress towards the development of a professional identity.6,7 For learners, positive feedback about progress is important to both belonging within the pharmacy profession and confidence.5,7 With the current methods available, summative assessment at the learner level is difficult. At the program level, some survey tools for quantitative assessment are being explored, though at present the majority of PIF assessment relies on qualitative approaches, including mentored discussion groups and reflective writing assignments. This will present a challenge for many colleges and schools as qualitative assessments often require a significant time investment. All members of the Academy will benefit from resource-sharing and deliberate collaboration as we develop mechanisms to identify students needing support and demonstrate the program’s effect on identity formation.

APPLYING IMPLEMENTATION SCIENCE PRINCIPLES

In order to intentionally prepare graduates to “think, act, and feel” like pharmacists as described in this report, a sustainable culture shift is needed in our academic approach. Traditionally, curricula have prioritized competencies, cognitive abilities and skill development. By making PIF the goal of education, our approach must become broader and incorporate more deliberate support. PIF is not easy work, requiring intentional design, guided reflection, strong role modeling, new forms of student learning assessment, new forms of program evaluation, and faculty and preceptor development.

Therefore, the successful adoption of PIF will require intentional planning and commitment by all stakeholders. Implementation science, with its focus on methods and strategies to promote successful adoption of evidence-based practices and interventions into real world settings, will be critical for transitioning.51,52 Application of implementation science to pharmacy education and practice has generated considerable interest within the Academy. The 2019-2020 AACP Research and Graduate Affairs Committee (RGAC) was charged with articulating the case for implementation science as a key strategy for practice and curricular advancement efforts led by academic institutions. In their report, the RGAC recommended that AACP should continue to find opportunities to connect academic pharmacy with the implementation science community.51

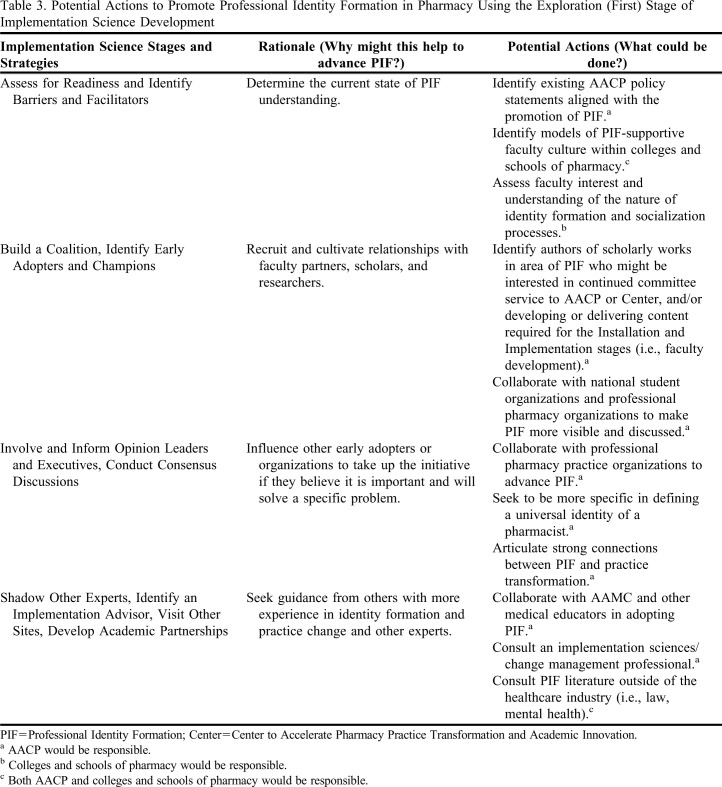

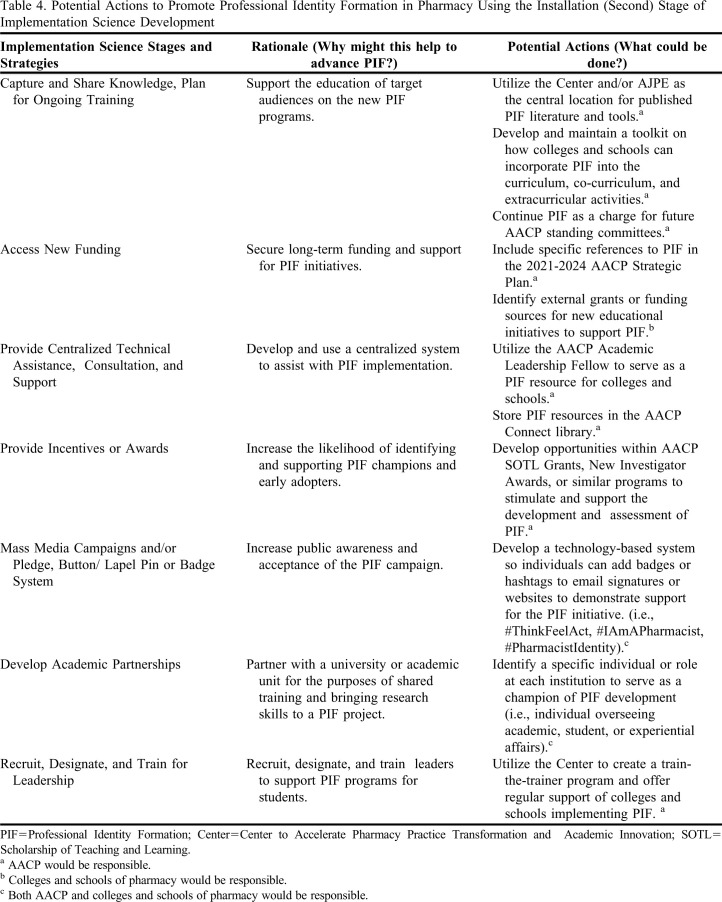

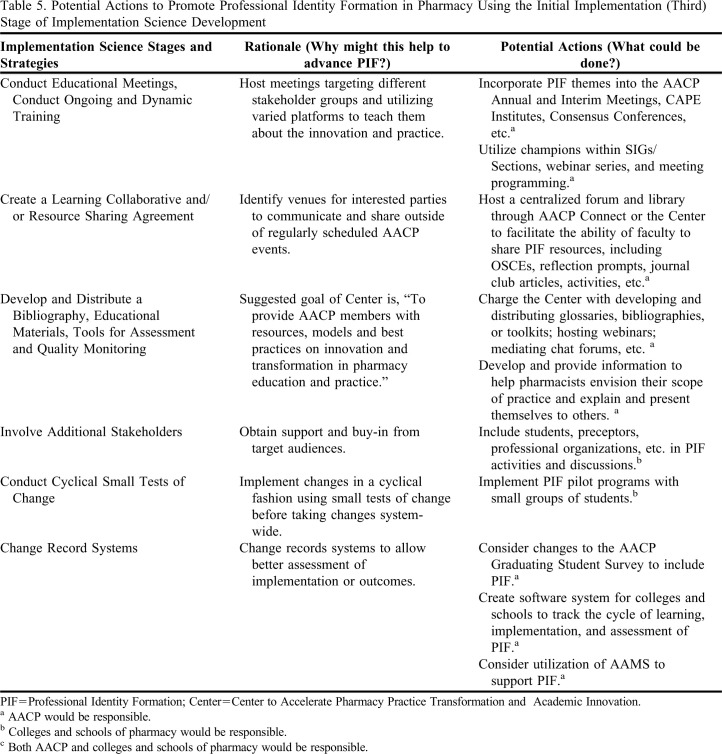

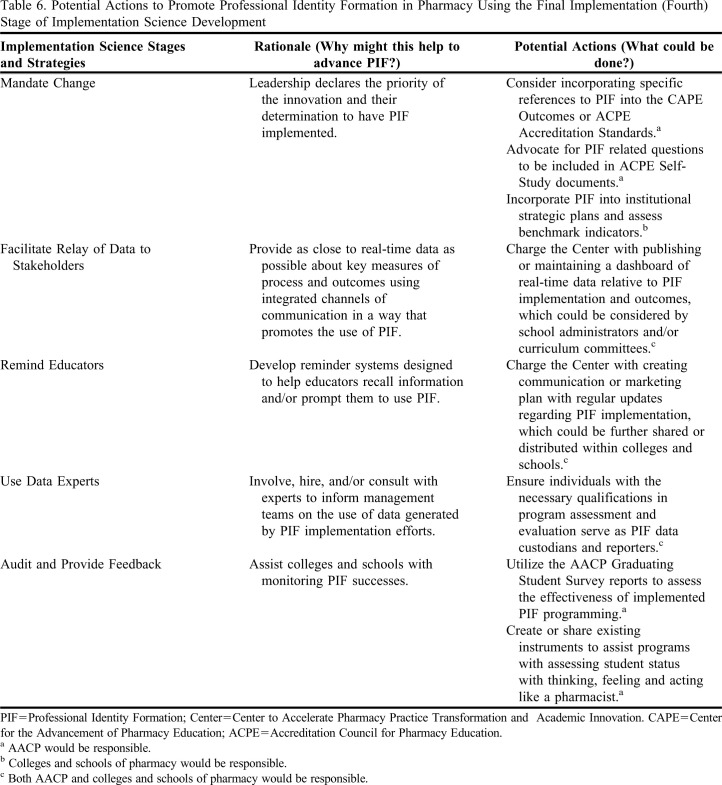

As the 2020-2021 SAC worked through its charges, implementation science was consulted to examine needs related to PIF, recommend potential actions for implementation, and identify important stakeholders and implementation leaders (Tables 3,4,5,6). The committee contends that the proposed Center is well-positioned to provide the vision, leadership, and resources needed for supporting PIF as a component of practice transformation. Implementation science also provided a framework for SAC to suggest potential actions for AACP, the Center, and individual faculty or institutions to support the diffusion and adoption of PIF into pharmacy education. Potential actions are provided and organized by implementation stage and supporting rationale for the action is included (Tables 3,4,5,6).53,54 The subsequent discussion on the advancement of PIF in the academy draws upon the Powell, et al. compilation report of implementation science strategies.54

Table 3.

Potential Actions to Promote Professional Identity Formation in Pharmacy Using the Exploration (First) Stage of Implementation Science Development

Table 4.

Potential Actions to Promote Professional Identity Formation in Pharmacy Using the Installation (Second) Stage of Implementation Science Development

Table 5.

Potential Actions to Promote Professional Identity Formation in Pharmacy Using the Initial Implementation (Third) Stage of Implementation Science Development

Table 6.

Potential Actions to Promote Professional Identity Formation in Pharmacy Using the Final Implementation (Fourth) Stage of Implementation Science Development

According to the National Implementation Research Network, implementation progresses through four stages of development: exploration, installation, initial implementation, and full implementation.53 A brief description of each stage is provided to offer context for the SAC’s approach, findings, and recommendations. In the Exploration phase, organizations work to assess the needs of target populations, the fit of a new initiative with the identified need, and the feasibility of implementation. Given the charges to the committee by our two most recent presidents, AACP is currently in the Exploration phase in regards to implementation of PIF. The two most recent SAC committees were charged with determining whether increased emphasis on PIF in pharmacy curricula would support professional goals of practice transformation. Both 2019-20 and 2020-21 SAC agreed that PIF is an appropriate focus for the Academy and recommend proceeding to the second stage of implementation, Installation. During this phase, the organization works to build interest, infrastructure, and capacity to support a full roll-out of the initiative. During the Initial Implementation phase, the Center and AACP would develop and provide extensive education, faculty development, and shared resources to support the efforts of colleges and schools in piloting PIF activities and curricula with emphasis on continuous quality improvement and the scholarship of teaching and learning. Eventually, the momentum of the initiative reaches Full Implementation, where a large enough proportion of the target population adopts the initiative to support population-level outcomes assessment. The principles of fidelity and sustainability will be particularly important with implementation of PIF initiatives. Colleges and schools are asked to pay careful attention to initial education and training interventions and the fidelity of delivery of those interventions in subsequent iterations. Colleges and schools should also consider the sustainability of curricular changes during initial design and implementation.

AFFIRMING THE 2019-2020 SAC RECOMMENDATIONS AND SUGGESTIONS

The 2019-2020 SAC recommended that AACP should advocate for the adoption of PIF in educational and professional goal statements.2 Since this time, ACPE has announced its intention to revise Standards 2016 with new standards that will be known as “Standards 2025.”55 The 2020-2021 SAC affirms the prior suggestion and emphasizes that the timing is right for follow-through on the 2019-2020 recommendation. AACP, during its opportunities for input into the revision of accreditation standards, should advocate for the development of a strong professional identity as a goal of pharmacy education.

The 2019-2020 SAC also recommended that AACP adopt professional identity and PIF as priorities in the next strategic plan.2 Since this time, AACP has begun the strategic planning process. The 2020-2021 SAC affirms this recommendation and emphasizes that the timing is right for follow through on the 2019-2020 recommendation. In addition, current SAC members have recommended PIF’s inclusion during the open hearings on the AACP 2021-2024 Strategic Plan and offer an updated recommendation below.

The 2019-2020 SAC also recommended that AACP adopt professional identity and PIF as priorities in the next strategic plan.2 Since this time, AACP has begun the strategic planning process. The 2020-2021 SAC affirms this recommendation and emphasizes that the timing is right for follow through on the 2019-2020 recommendation. In addition, current SAC members have recommended PIF’s inclusion during the open hearings on the AACP 2021-2024 Strategic Plan and offer an updated recommendation below.

With the Bridging Pharmacy Education and Practice Summit on the horizon, the 2020-2021 SAC affirms the previous committee’s recommendation that AACP “collaborate with other pharmacy organizations to help the profession develop and embody a clear and unified identity for practice today and tomorrow.” 2 The 2020-2021 SAC adds a specific recommendation related to the summit below.

In addition, the 2019-2020 committee made a recommendation that AACP continue to facilitate inquiry and dissemination of strategies related to PIF assessment and suggestions that colleges/schools: 1) pursue scholarly questions in support of PIF assessment and 2) share their initiatives and evaluative evidence related to PIF. The 2020-2021 SAC affirms this recommendation and these suggestions.2

2020-2021 RECOMMENDATIONS

AACP should work with JCPP to determine the essential elements of professional identity for pharmacists, in order to meet current and future needs and to advance the profession.

AACP should include professional identity formation in the AACP Strategic Plan, including, but not limited to, strategies related to faculty development programming and resource sharing between colleges and schools of pharmacy.

AACP should charge the Center with incorporating PIF as a strategic priority with a robust action plan, as noted in Tables 3-6 of this report, to support professional identity formation (PIF) in its important role with practice transformation.

AACP should continue to provide programming and other resources to assist colleges and schools of pharmacy to develop a comprehensive, integrated, developmental set of curricular and co-curricular components that will enhance professional identity formation in pharmacy students, trainees, and faculty.

AACP should incorporate PIF into the 2022 summit, ensuring that participants have a firm understanding of the principles and actions needed to support it, in preparation for profession-wide action planning.

AACP should include a PIF session at the 2022 Leadership Forum as follow-up to the 2022 summit.

AACP should encourage the Council of Faculties to coordinate conversation regarding PIF through a task force in order to support faculty development and intentional planning within colleges and schools of pharmacy.

AACP should encourage the Council of Faculties to consider PIF as a prominent theme in the 2022 and/or 2023 Teachers Seminars.

AACP should encourage Special Interest Groups and Sections to examine their role in student professional identity formation and charge committees and/or task forces with appropriate work in this area.

AACP should feature PIF in the 2022 or future school posters.

2020-2021 SUGGESTIONS

Colleges and schools of pharmacy should extend their professionalism work by fostering a culture of intentional support of PIF that aids students in explaining, presenting and conducting themselves within the scope of student work and professional priorities.

Colleges and schools of pharmacy should explore, adopt, and implement an explicit approach for supporting professional identity formation through its curricular and co-curricular components, including setting goals and objectives, activities, and assessments (including self-reflection and feedback) supporting professional identity formation.

Colleges and schools of pharmacy should support a range of efforts with a diverse variety of stakeholders (eg, professional associations, employers, student services professionals, preceptors) that help students to navigate transitions, learn the language of the profession, integrate personal and professional identities and manage difficult emotions and attitudes related to professional identity formation.

Colleges and schools of pharmacy should anticipate the dissonance that students experience in transitioning to practice, developing strategies to support them and practice transformation.

Colleges and schools of pharmacy should invest in faculty development on the nature of identity formation (including its internal and social dimensions), socialization processes and professional communities of practice, including teaching pedagogies and assessment.

Colleges and schools of pharmacy should provide preceptor development programming, emphasizing the unique role of preceptors in students’ conscious and unconscious acquisition of behaviors, attitudes, and beliefs, and the preceptor’s influence through role modeling and socialization processes.

Colleges and schools of pharmacy should utilize implementation science principles to create a robust action plan, as noted in Tables 3-6 of this report, to support the diffusion and adoption of professional identity formation (PIF) at the institution and within the profession.

Scholars in education at colleges and schools of pharmacy should undertake initiatives that explore the process and influencers of professional identity formation in students.

CONCLUSION

The pharmacy profession has rapidly evolved over the last 30 years, which has led to the fragmentation and accumulation of conflicting identities for pharmacists based on their role, geographic location, and practice setting. The lack of a universal identity and inconsistent efforts to promote professional identity formation in Pharm.D. degree programs have hindered our ability to advance practice transformation and prepare student pharmacists to navigate and influence the rapidly evolving healthcare landscape. A coordinated and collaborative approach to professional identity formation will facilitate the ability of pharmacists to more effectively convey their value to themselves, patients, payers, and other providers. Pharmacy must pursue two goals to realize the benefits of PIF. One is to collaborate with practice associations and other stakeholders to define a unique, universal, and contemporary identity of a pharmacist that transcends practice settings. Academic pharmacy plays a crucial role in shaping the identity of future pharmacists and cannot wait for the profession to reach a consensus on its identity before taking action. Instead, colleges and schools of pharmacy must simultaneously apply existing educational frameworks to intentionally support the professional identity formation of student pharmacists. Pharmacy educators must anticipate the dissonance that students experience in transitioning to practice and help them navigate the process from peripheral participant to full participation by supporting them as they internalize the profession’s norms, standards and values on their way to becoming a pharmacist.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy, Review of the Cumulative Policies, 1980-2020. https://www.aacp.org/cumulative-policies-1980-2020. Accessed March 19, 2021.

- 2.Welch BE, Arif SA, Bloom TJ, et al. . Report of the 2019-2020 AACP student affairs standing committee. Am J Pharm Educ. 2020;84(10):1402-1408. doi: 10.5688/ajpe8198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steinert Y, Janke K. What’s the end goal? Professionalism or professional identity. Lecture presented at: AACP Interim Meeting; March 1, 2021; virtual.

- 4.Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Boudeau D, Snell L, Steinert Y. Reframing medical education to support professional identity formation. Acad Med. 2014;89(11):1446-1451. doi: 10.1097/acm.0000000000000427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Boudreau JD, Snell L, Steinert Y. A schematic representation of the professional identity formation and socialization of medical students and residents. Acad Med . 2015;90(6):718-725. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Steinert Y. Amending Miller’s pyramid to include professional identity formation. Acad Med 2016;91(2): 180-185. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cruess SR, Cruess RL. Chapter 17: The Development of Professional Identity. In: Swanwick T, Forrest K, O'Brien BC, eds. Understanding Medical Education. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2018: 239-254. doi: 10.1002/9781119373780.ch17. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cantillon P, Dornan T, De Grave W. Becoming a clinical teacher: identity formation in context. Acad Med. 2019;94(10):1610-1618. doi: 10.1097/acm.0000000000002403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Urick BY, Meggs EV. Towards a greater professional standing: evolution of pharmacy practice and education, 1920-2020. Pharmacy. 2019;7(3):98. doi: 10.3390/pharmacy7030098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chase PA, Allen DD, Boyle CJ, Dipiro JT, Scott SA, Maine LL. Advancing our pharmacy reformation-accelerating education and practice transformation: report of the 2019-2020 argus commission. Am J Pharm Educ. 2020;84(10):1394-1401. doi: 10.5688/ajpe8205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keller J, Paradis E, van der Vleutin CPM, oude Egbrink MGA, Austin Z. A historical discourse analysis of pharmacist identity in pharmacy education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2020;84(9):Article 7864. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elvey R, Hassell K, Hall J. Who do you think you are? Pharmacists' perceptions of their professional identity. Int J Pharm Pract. 2013;21(5):322-332. doi: 10.1111/ijpp.12019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Atkinson J, De Paepe K, Sánchez Pozo A, et al. . What is a pharmacist: opinions of pharmacy department academics and community pharmacists on competences required for pharmacy practice. Pharmacy. 2016; 4(1):12. doi: 10.3390/pharmacy4010012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Noble C, O’Brien M, Coombes I, Shaw PN, Nissen L, Clavarino A. Becoming a pharmacist: the role of curriculum in professional identity formation. Pharm Pract (Granada). 2014;6(3):327-339. doi: 10.4321/s1886-36552014000100007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Pharmacists Association. Oath of a Pharmacist; 2007. https://www.pharmacist.com/About/Oath-of-a-Pharmacist. Updated July 2007. Accessed February 17, 2021.

- 16.American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. ASHP statement on professionalism. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2008; 65(2): 172-174. doi: 10.2146/ajhp070397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. ASHP statement on the pharmacist’s role in primary care. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 1999;56:1665-1667. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/56.16.1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Medina MS, Plaza CM, Stowe CD, et al. . Center for the Advancement of Pharmacy Education 2013 educational outcomes. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(8):Article 162. doi: 10.5688/ajpe778162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joint Commission of Pharmacy Practitioners. Pharmacists’ Patient Care Process; May 29, 2014. https://jcpp.net/patient-care-process/. Accessed February 17, 2021.

- 20.National Association of Boards of Pharmacy. Model State Pharmacy Act and Model Rules; 2020. https://nabp.pharmacy/resources/model-pharmacy-act/. Published December 18, 2020. Accessed February 22, 2021.

- 21.American College of Apothecaries. Standards of Practice for Full Fellows and Pharmacist Members of the ACA. 2020. https://acainfo.org/standards-of-practice/. Accessed April 2, 2021.

- 22.Burke JM, Miller WA, Spencer AP, et al. . Clinical pharmacist competencies. Pharmacotherapy. 2008;28(6):806-815. doi: 10.1592/phco.28.6.806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.American College of Clinical Pharmacy. The definition of clinical pharmacy. Pharmacotherapy. 2008;28(6):816-817. doi: 10.1592/phco.28.6.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harris IM, Phillips B, Boyce E, et al. . ACCP White Paper: Clinical pharmacy should adopt a consistent process of direct patient care. Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34(8):e133-e148. doi: 10.1002/phar.1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy. What is Managed Care Pharmacy? AMCP Webinar. 2020. https://www.amcp.org/sites/default/files/2020-09/WhatIsManagedCarePharmacy-WebinarSlides-September2020.pdf. Updated September 2020. Accessed February 17, 2021.

- 26.American Pharmacists Association. Pharmacist Scope of Services; 2020. https://aphanet.pharmacist.com/sites/default/files/files/APhA%20-%20PAPCC%20Scope%20of%20Services.pdf. Accessed February 17, 2021.

- 27.American Society of Consultant Pharmacists. ASCP Creed; 2020. https://www.ascp.com/page/whoweare. Accessed February 17, 2021.

- 28.American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. ASHP guidelines on a standardized method for pharmaceutical care. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 1996;53:1713-1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Psychiatric Pharmacists. College of Psychiatric and Neurologic Pharmacists website. https://cpnp.org/psychpharm. Accessed February 17, 2021.

- 30.Joint Commission of Pharmacy Practitioners. JCPP Vision for Pharmacists' Practice; November 2013. https://jcpp.net/resourcecat/jcpp-vision-for-pharmacists-practice/. Accessed February 17, 2021.

- 31.Joint Commission of Pharmacy Practitioners. Medication management services (MMS) definition and key points; March 14, 2018. https://jcpp.net/resource/medication-management-services-mms-definition-and-key-points/. Accessed February 17, 2021.

- 32.National Association of Boards of Pharmacy. NAPLEX Competency Statements; 2021. https://nabp.pharmacy/programs/examinations/naplex/competency-statements/. Published January 1, 2021. Accessed April 6, 2021.

- 33.National Association of Boards of Pharmacy. MPJE Competency Statements; 2020. https://nabp.pharmacy/programs/examinations/mpje/competency-statements/. Published October 30, 2020. Accessed February 22, 2021.

- 34.National Community Pharmacists Association. Rethink Pharmacy: The 4 Tenets of the Clinical Community Pharmacy. 2015. https://ncpa.org/clinical-community-pharmacy-series. Accessed February 22, 2021.

- 35.US Public Health Service. Improving Patient and Health System Outcomes through Advanced Pharmacy Practice: A Report to the U.S. Surgeon General. Pharmacist Roles. 2011. https://jcpp.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Improving-Patient-and-Health-System-Outcomes-through-Advanced-Pharmacy-Practice.pdf. Accessed February 22, 2021.

- 36.Identity. Merriam-Webster Dictionary. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/identity. Accessed on April 6, 2021.

- 37.Sorensen TD, Hager KD, Schlichte A, Janke K. A Dentist, pilot, and pastry chef walk into a bar…why teaching PPCP is not enough. Am J Pharm Educ. 2020;84(4):7704. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. Triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(6): 573-576. doi: 10.1370/afm.1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Steinert Y. Supporting the development of a professional identity: general principles. Med Teach. 2019;41(6):641-649. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2018.1536260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wenger E. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 41.APhA-ASP/AACP-COD Task Force on Professionalism. White paper on pharmacy student professionalism. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2000;40:96-102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. Council of Deans Task Force on Professional Identity Formation. May 31, 2014.

- 43.Schein EH. Career Dynamics: Matching Individual and Organizational Needs. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ibarra H. Provisional selves: experimenting with image and identity in professional adaptation. Administrative Sci Quart. 1999;44:764-791. doi: 10.2307/2667055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Holden M, Buck E, Clark M, Szanter K, Trumble J. Professional identity formation in medical education: the convergence of multiple domains. HEC Forum. 2012;24:245-255. doi: 10.1007/s10730-012-9197-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baxter Magolda MB, King PM (Eds.). Learning Partnerships: Theory & Models of Practice to Educate for Self-Authorship. Sterling, VA: Stylus; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Noble C, McKauge L, Clavarino A. Pharmacy student professional identity: a scoping review. Integr Pharm Res Pract. 2019;8:15-834. doi: 10.2147/IPRP.S162799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mylrea MF, Gupta T Sen, Glass BD. Design and evaluation of a professional identity development program for pharmacy students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2019;83(6):1320-1327. doi: 10.5688/ajpe6842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Johnson JL, Chauvin S. Professional identity formation in an advanced pharmacy practice experience emphasizing self-authorship. Am J Pharm Educ. 2016;80(10):Article 172. doi: 10.5688/ajpe8010172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bloom TJ, Smith JD, Rich W. Impact of pre-pharmacy work experience on development of professional identity in student pharmacists. Am J Pharm Educ. 2017;81(10):Article 6141. doi: 10.5688/ajpe6141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kuo G, Bacci JL, Chui MA, et al. . Implementation science to advance practice and curricular transformation: Report of the 2019-2020 AACP Research and Graduate Affairs Committee. Am J Pharm Educ. 2020;84(10):848204. doi: 10.5688/ajpe848204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Livet M, Haines ST, Curran GM, et al. . Implementation science to advance care delivery: a primer for pharmacists and other health professionals. Pharmacotherapy. 2018;38(5):490-502. doi: 10.1002/phar.2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.National Implementation Research Network. Implementation stages planning tool. https://nirn.fpg.unc.edu/sites/nirn.fpg.unc.edu/files/resources/Implementation%20Stages%20Planning%20Tool.pdf. Published September 2020. Accessed January 22, 2021.

- 54.Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, et al. . A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implementation Sci. 2015;10:21. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.American Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation standards and key elements for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the doctor of pharmacy degree. 2015. https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/Standards2016 FINAL.pdf. Accessed March 29, 2021.