Abstract

A nosocomial outbreak of hepatitis B occurred among the inpatients of a hematology unit. Nine of the 11 infected patients died from fulminant hepatitis. An investigation was conducted to identify the source of infection and the route of transmission. Two clusters of nosocomial hepatitis B were identified. The hepatitis B virus (HBV) genome from serum samples of all case patients, of one HBsAg-positive patient with acute reactivation of the infection, and of eight acutely infected, unrelated cases was identified by PCR amplification of viral DNA and was entirely sequenced. Transmission was probably associated with breaks in infection control practices, which occurred as single events from common sources or through a patient-to-patient route, likely the result of shared medications or supplies. Sequence analysis evidenced close homology among the strains from the case patients and that from the patient with reactivation, who was the likely source of infection. Molecular analysis of viral isolates evidenced an accumulation of mutations in the core promoter/precore region, as well as several nucleotide substitutions throughout the genome. The sequences of all patients were compared with published sequences from fulminant and nonfulminant HBV infections.

The spectrum of liver injuries caused by hepatitis B virus (HBV) ranges from self-limited acute infection to chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, and hepatocarcinoma. Fulminant hepatitis B (FHB) is uncommon, occurring in about 1% of patients with acute hepatitis (26). In the health care setting, HBV infection remains a serious problem. Patient-to-patient transmission is well recognized (2, 13, 16) and is more frequent than either health care worker-to-patient (14, 43) or patient-to-health care worker transmission (12). Infection control measures, including segregation of HBsAg-positive dialysis patients (3) and vaccination (23), have effectively reduced nosocomial HBV acquisition. However, in the hematologic setting specific risk factors, including the high frequency of percutaneous procedures and the presence of intravenous lines, may facilitate the spread of blood-borne pathogens (1). Indeed, several cases of reactivation of HBV infection and/or de novo fulminant hepatitis following withdrawal of immunosuppressive therapy for hematologic and oncologic diseases have been described (9, 22, 30, 37, 45).

The pathogenesis of FHB remains unclear, though both viral and host factors are believed to play an important role (7, 21, 24, 28, 33, 39). In this study, we describe an outbreak of HBV infection that occurred between December 1997 and February 1998 among the patients of a hematology unit (San Salvatore Hospital, Pesaro, Italy), leading to a fatal course in 9 of the 11 cases. We conducted an investigation to identify the source of infection and the route of transmission. Molecular characterization of HBV genomes was conducted through sequence analysis of the entire viral genome isolated from all case patients and the putative source case. We also compared the isolates described in this study with published nucleotide and amino acid sequences from patients with fulminant and nonfulminant type B hepatitis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients.

At the end of January 1998, the medical records of all inpatients of the hematology ward from August 1997 to January 1998 were reviewed and the patients were traced to collect information on demographic characteristics, HBV serological status, the presence of a vascular catheter, intravenous and subcutaneous administration of drugs, capillary blood drawing, apheresis, receipt of blood products, bone marrow biopsy and/or transplant, and clinical condition. All the patients who had been present in the ward during the above-mentioned period and were HBV susceptible, of unknown HBV serostatus, or HBsAg positive during hospitalization were asked to give monthly blood samples for HBV serology free of charge for a 6-month period.

The hematology unit's infection control practices were assessed by interviewing unit personnel, observing their practices, and examining equipment.

Laboratory methods.

HBsAg, antibodies to hepatitis B surface antigen (anti-HBs), hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg), anti-HBe, anti-HBc (immunoglobulin G [IgG] and IgM), and anti-HAV (IgG and IgM) were detected by microparticle enzyme immunoassay (Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, Ill.). Anti-HCV antibodies were detected by enzyme immunoassay (EIA) (EIA-HCV 3.0, Ortho Diagnostic System, Raritan, N.J.); anti-HDV antibodies (IgG and IgM) and HDVAg were detected by EIA (Sorin Biomedica, Saluggia, Italy); and anti-human immunodeficiency virus types 1 and 2 (HIV-1 and -2) antibodies were detected by EIA capture 3.0 (Sanofi Diagnostics Pasteur, Marnes-Le-Coquette, France). Cytomegalovirus (CMV) and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) antibodies were also sought by commercially available EIA kits with recombinant antigens (Wampole Laboratories, Dist., Cranbury, N.J.; Diamedix Corp., Miami, Fla.). An amplified solution hybridization assay (Digene hybrid capture system; Digene, Gaithersburg, Md.) was used for semiquantitative detection of HBV DNA in serum.

Molecular analysis was carried out on samples collected from case patients at the onset of clinical symptoms and (when available) at different time points during hospitalization. Serum or plasma samples (50 μl) collected from HBsAg-positive subjects were digested with proteinase K for 2 h at 65°C; HBV DNA was extracted with phenol-chloroform solution and alcohol precipitation. For DNA amplification by PCR, seven overlapping oligonucleotides spanning the whole HBV genome (Table 1) were synthesized using phosphoramidite chemistry in a Beckman DNA synthesizer (Oligo 1000; Beckman Instruments Inc., Fullerton, Calif.). Amplification reactions were carried out in an automated thermal cycler (model 9600; Perkin-Elmer Cetus, Norwalk, Conn.). Amplified products were purified and sequenced using fluorescence-labeled dideoxynucleotides with an automated sequencer (model 373A; Perkin-Elmer, Norwalk, Conn.), using the dyedeoxy terminator cycle sequencing system with ampli-Taq polymerase FS. Both plus and minus strands were sequenced using sense and antisense oligonucleotides as bidirectional sequencing primers. Amplified products from samples of the putative source case and case patients were also ligated to the pCR-Script SK(+) plasmid vector (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) and transformed to competent E. coli cells. Plasmid DNA from single transformant colonies (10 to 20) was extracted and purified from overnight-cultured minipreps using the Wizard DNA purification system (Promega, Madison, Wis.).

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used for HBV DNA amplification and sequencing assaysa

| Sense (5′–3′) | Antisense (5′–3′) | ORF(s) |

|---|---|---|

| 1383–1404 | 1627–1606 | X |

| 1660–1683 | 1941–1915 | Pre-C/C |

| 2140–2163 | 2840–2817 | C/Pol |

| 2817–2840 | 202–176 | Pol/pre-S2 |

| 414–440 | 868–845 | S/Pol |

| 840–862 | 1440–1415 | Pol/X |

| 55–80 | 504–480 | Pol/S |

Oligonucleotide positions are designated according to the sequence reference of HBV, genotype D, subtype ayw.

The complete HBV nucleotide sequences were edited and assembled using the Sequence Navigator program included in the ABI373 software package. Multiple nucleotide and amino acid sequences were aligned using the Megalign program (DNAstar Inc., Madison, Wis.), and a pairwise matrix of evolutionary distances of nucleotide sequences was generated using DNADIST (Kimura's two-parameters method), which is included in version 3.572 of the PHYLIP package (3.5 edition; Department of Genetics, University of Washington, Seattle, Wash.).

Other assays.

Specific sequences of HCV, hepatitis G virus (HGV/GBV-C), and the newly described transfusion-transmitted virus (TTV) were also sought by reverse transcriptase PCR and hemi-nested PCR techniques, using primers from the 5′-untranslated region of HCV, the NS3/helicase region of HGV, and the putative ORF-1 region of TTV, respectively, as previously described (29, 32, 44).

Statistical methods.

Attack rates were calculated for patients exposed and not exposed to potential risk factors, excluding deaths and patients lost to follow-up. The chi square test or, when appropriate, Fisher's exact test was used to evaluate the association of outcome with potential risk factors. The unpaired t test was used to compare group means of nucleotide sequence divergences. Two-tailed P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Calculations were performed using STATA statistical software (release 5.0; Stata Corporation, College Station, Tex.).

Comparative analysis.

The sequences of all case patients were compared with published sequences of fulminant and nonfulminant hepatitis B, including those recently reviewed by Sterneck et al. (38) and those described by Stuvyver et al. (40) (accession no. AF090838 to AF090842).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The new sequences described in this paper have been submitted to EMBL and assigned accession no. AJ005084 to AJ005110 and AJ009994 to AJ10007.

RESULTS

Acute hepatitis B cases.

Eleven cases (four males; mean age, 49.5 years; range, 12 to 68 years) of acute hepatitis B were observed between 9 December 1997 and 20 February 1998, with a 14.5% crude attack rate. In 7 cases, infection likely occurred in late October 1997 (7/11, 63.6% attack rate), and in 4 cases, infection likely occurred in December 1997 (4/10, 40% attack rate). All patients had jaundice; alanine aminotransferase ranged from 207 to about 8,000 U/liter. All tested positive for HBsAg and IgM anti-HBc at admission; HBeAg was transiently detected at low levels (less than 1.5 times the cut-off value) in 4 patients at admission, and it was no longer detectable during hospitalization. HBV DNA levels at admission ranged from 192 to 6,890 pg/ml. Of the 11 HBV-infected patients, 4 had myeloma, 3 had non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, 3 had leukemia, and 1 had Kaposi's sarcoma.

Seven of the 11 cases totaled 13 hospital stays in the hematology ward between 8 August and 15 November 1997 (group A). On these occasions, 5 HBsAg carriers were present simultaneously in the ward; one of them was a patient with acute reactivation of an HBV infection (HR patient). He had been positive for anti-HBs and anti-HBc before October 1997, but during his last stay in the ward he became positive for HBsAg, anti-HBe, and anti-HBc-IgM. This patient is the most likely source of the infections. On 20 October 1997, the 7 patients of group A were in the same ward as the HR patient. The remaining 4 patients who would later become infected (group B) totaled 10 stays between 3 November 1997 and 17 January 1998, when 4 patients of group A were also staying in the ward; in particular, the stays of 2 cases of group A overlapped those of the 4 patients of group B from 15 to 17 December 1997.

The review of infection control procedures carried out in the hematology unit evidenced breaks in infection control measures; moreover, multidose vials (heparin, lidocaine) were in use in this unit.

HBV nucleotide sequences.

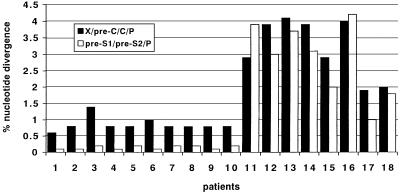

The complete HBV nucleotide genome from 10 case patients (the samples from the 11th patient were not available), from the HR patient, and from 8 HBsAg-positive, acutely infected subjects from the Pesaro area, unrelated to the epidemic, was evaluated. HBV DNA was not detectable in the 2 HBsAg carriers hospitalized between August and December 1997. All samples from the 10 case patients and the HR patient showed high sequence homology. Cloning of the PCR products from the HR patient yielded two closely related sequences for X/pre-C/C/P. Pairwise comparisons were performed between the aligned sequences from case patients and that from the HR patient. The percent divergence ranged from 0.6 to 1.4 against each of the two clones for X/pre-C/C/P (mean, 0.86 ± 0.211) and from 0.1 to 0.2 for pre-S1/pre-S2/P (mean, 0.15 ± 0.052) (Fig. 1). By contrast, the percent divergence between the HR patient and the 8 epidemiologically unrelated patients with acute hepatitis B ranged between 1.9 and 4.1 for X/pre-C/C/P (mean, 3.2 ± 0.905) and between 1.0 and 3.9 for pre-S1/pre-S2/P (mean, 2.83 ± 1.132). The difference between groups was statistically significant (t test for X/pre-C/C/P = 7.154; P = 0.0001; t test for pre-S1/pre-S2/P = 6.705; P = 0.0002), thus confirming the monophyly of the sequences obtained from the 10 case patients and the HR patient. Molecular analysis of the X/pre-C/C/P region was also carried out on serum samples collected from case patients at different time points (2 to 6 weeks) from the onset of clinical symptoms: results show 100% intrapatient sequence homology, evidencing lack of genomic evolution in the short-term follow-up (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Percent nucleotide divergence of aligned HBV sequences between the source patient (HR in the text) and the case patients (1 to 10) and between HR and unrelated patients with self-limited acute hepatitis (11 to 18).

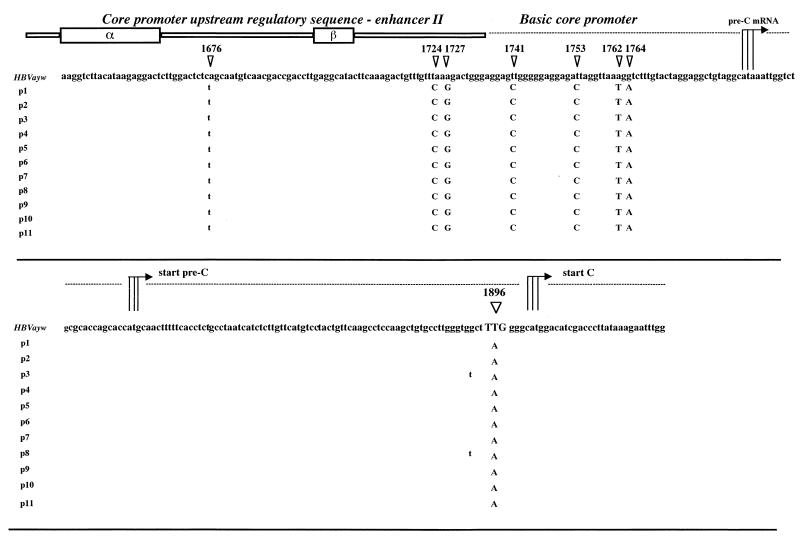

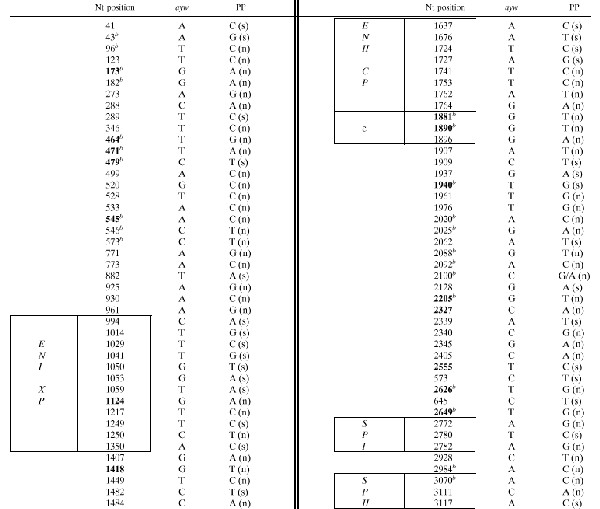

A total of 86 nucleotide substitutions (2.7% of the entire genome) were detected when the sequences from all isolates were aligned with the prototype HBV strain, genotype D, subtype ayw (Table 2): 63 mutations were detected in sequences from all patients, and 23 were detected only in some clones. When these sequences were compared with the published sequences from other cases with and without FHB, very few of the mutations could be considered rare or unique (boldface nucleotide positions in the table). Several nucleotide substitutions were randomly distributed within the entire genome, but no unique mutations were identified in functional regions, including the surface promoter I and surface promoter II, enhancer I-X promoter (EnI-X), enhancer II-core promoter (EnII/CP); and the encapsidation signal sequence, except for a G-to-A substitution in the EnI/X promoter region (nucleotide position 1124 of the genome). In particular, Fig. 2 shows the nucleotide alignments of a 300-bp fragment bearing the EnII/CP region of the X open reading frame (ORF) and the entire precore ORF derived from the sera of the 10 case patients and the HR patient; the G-to-A point mutation at nucleotide 1896, which converted codon 28 in the precore region from tryptophan (TGG) to a stop codon (TAG), was observed in all of the 11 cases' samples. Three point mutations were also detected in the basic core promoter, at positions 1753 (A-to-C), 1762 (A-to-T), and 1764 (G-to-A); additional mutations were observed in the EnII/CP fragment, upstream of the CP region (positions 1724, 1727, and 1741).

TABLE 2.

Nucleotide substitutions in the HBV genome of all cases with fulminant hepatitisa

|

Mutations in the HBV genome isolated from 10 case patients and the source patient (PP, nucleotide substitutions in the consensus sequence from all cases) compared with the prototype HBV sequence (genotype D, subtype ayw). Nucleotide positions located within regulatory elements are boxed. Positions of unique or rare mutations are in bold; comparison was conducted with previously published isolates from cases with and without FHB (see Materials and Methods). Nt, nucleotide; (s), synonymous; (n), nonsynonymous.

Detected in some clones.

FIG. 2.

Nucleotide alignments of the sequences spanning the EnII/CP region and the precore ORF from 11 patients with fulminant hepatitis B. Nucleotide substitutions detected within the EnII/CP and the G-to-A substitution at position 1896 of the precore region are indicated. α and β boxes within the core promoter upstream of the regulatory sequence are also indicated. Patients' sequences (p1 to p11) are compared with the reference sequence of HBV, subtype ayw.

Predicted HBV amino acid sequences.

Overall, 56 nucleotide mutations predicted amino acid changes in the viral ORFs (Table 3); none of the ORFs was interrupted, except for the precore stop codon mutation detected in all cases. Unique or rare amino acid changes could be predicted in 20 motifs (13 in all cases and 7 only in some clones): 1 in the pre-S/S ORFs (in all cases), 2 in the X ORF (in all cases), 8 in the pre-C/C ORFs (3 in all cases), and 9 in the P ORF (7 in all cases). In the pre-S/S and P ORFs, none of the amino acid substitutions were located in motifs essential to critical secretion or antigenic functions, including the reverse transcription and RNase H domains. Amino acid change at codon 67 of the C ORF was detected in all isolates, whereas codons 63 and 64 were mutated only in some clones; these mutations are located in a motif (residues 60 to 90) in the middle of the core protein, at the tip of surface-exposed, protruding spikes of the viral capsid.

TABLE 3.

Amino acid changes within the HBV ORFs of all cases with fulminant hepatitisa

| Pre-S/S

|

X

|

Pre-C/C

|

P

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA position | ayw | PP | AA position | ayw | PP | AA position | ayw | PP | AA position | ayw | PP |

| 46b | K | Q | 12 | A | T | 23b | C | F | 7 | H | Q |

| 75b | Q | K | 15 | V | F | 26b | W | L | 12 | L | V |

| 144b | L | P | 26 | C | R | 28 | W | STOP | 107b | G | W |

| 153 | I | T | 123 | L | S | 115b | F | C | |||

| 127 | I | T | 3 | I | F | 156 | I | V | |||

| 7b | G | R | 130 | K | M | 14b | E | D | 159 | K | R |

| 10b | G | R | 131 | V | I | 21 | S | A | 208 | R | C |

| 40 | N | S | 26 | S | A | 269 | P | T | |||

| 45 | T | N | 43b | E | K | 306 | E | A | |||

| 104 | L | V | 63b | G | V | 388 | N | K | |||

| 125 | M | T | 64b | E | D | 389 | Y | H | |||

| 127 | T | P | 67 | T | N (S) | 447 | V | G | |||

| 131b | T | P(I) | 102b | W | L | 459 | N | H | |||

| 140b | T | I | 143 | L | I | 466 | D | H | |||

| 206 | Y | C | 147 | T | C | 470 | Y | S | |||

| 207 | S | R | 149 | V | I | 550 | Q | P | |||

| 169 | Q | K | 601 | I | V | ||||||

| 602 | Q | H | |||||||||

| 613 | I | V | |||||||||

| 667 | C | Y | |||||||||

| 698 | V | A | |||||||||

| 709 | S | L | |||||||||

| 787 | S | Y | |||||||||

Predicted amino acid (AA) changes in the ORFs of the HBV genome isolated from 10 case patients and the source patient (PP, mutations in the consensus sequence from all cases) compared with the prototype HBV sequence (genotype D, subtype ayw). Codon positions of unique or rare mutations are in bold. Comparison was conducted with previously published isolates from cases with and without FHB (see Materials and Methods).

Detected in some clones.

Other virologic assays.

All cases tested negative for markers of ongoing infections with HAV, HDV, HCV, CMV, EBV and HGV; TTV DNA sequences were detected in 2 patients, neither of whom died from fulminant hepatitis.

Epidemiologic data.

Overall, 159 patients were admitted between August 1997 and January 1998. Forty-one of them either had a past HBV infection (n, 30) or were immune (n, 11) and were excluded from the analysis. Among those remaining, serologic HBV follow-up could not be performed in 37, either because of death (n, 19) or lack of information (n, 18). Of the remaining 81 patients, 5 were already HBsAg positive before October 1997, but 2 of these could not be traced; the other 76 HBV-susceptible patients underwent serologic follow-up, which ranged from 2 to 6 months (mean, 5.5 months; median, 6 months).

Patient accommodation in the rooms was also investigated. In October 1997, 2 patients who would later become infected occupied the same room, while another room was shared by 2 patients, one of whom was the HR patient. In December 1997, none of the case patients shared a room with any of the 7 patients of group A. Two cohort studies were conducted: one (A) among patients whose stays in October 1997 overlapped those of the HR patient, and the other (B) among patients whose stays in December 1997 overlapped those of the recently HBV-infected cases from the October cluster. When data from the patients of the two cohorts were pooled, intravenous immunoglobulin administration was found to be significantly associated with decreased risk of infection (P = 0.02). Since no cases occurred among patients receiving intravenous immunoglobulin, the analysis was repeated considering only the patients who did not receive intravenous immunoglobulin. In this analysis, no significant association was found to known risk factors, including for the month of exposure.

DISCUSSION

By the end of March 1998, it was clear that the 11 recent HBV infections in the hematology ward were linked, as shown by an identical pattern of nucleotide substitutions in the HBV sequences of all case patients. The HR patient was the most likely source of infection in the first cluster (October 1997). In the second cluster (December 1997), the likely sources were the HBV-infected patients from the October cluster. Nonetheless, patient-to-patient transmission cannot be ruled out. Based on the review of infection control procedures that evidenced breaks, transmission from sources to cases probably occurred via contaminated vials or supplies shared between patients, as already described in other outbreaks (17, 20, 34). Accordingly, we can hypothesize that contamination occurred during one of the intravascular procedures, e.g., blood drawing and intravascular catheter insertion, management, and heparin flushing, all of which presented the opportunity for blood from the carrier to contaminate staff or equipment (e.g., via contaminated hands, gloves, kidney dish, heparin, or normal saline) and hence the intravenous devices of patients. The detection of an identical pattern of nucleotide substitutions in the sequences from the HR patient and the infected patients confirms that a mutated virus was efficiently transmitted to the hospitalized patients.

In previous studies, HBV strains with point mutations in the precore region and/or in the basic core promoter have been detected in patients with FHB (6, 15, 18, 24, 28, 36). Specifically, the combination of the HBV variant with a stop at codon 28 of the precore and two mutations in the core promoter (A-to-T at position 1762 and G-to-A at position 1764), together with several point mutations in all regions of the genomes (5, 38, 40), has been reported in European patients with a severe course of acute HBV infection. However, the association between precore defective HBV strains and the development of acute liver failure has not been documented in all studies (10, 24, 25, 27) or has been revealed only during the late course of acute infection (35). Gunther et al. (11) recently described a novel class of HBV variants bearing mutations in the EnII/CP region which resulted in defective HBeAg expression and enhanced replication in immunosuppressed patients with severe liver disease. This particular phenotype depended mainly on the presence of deletions, insertions, and duplications in the EnII/CP region and, to a lesser extent, on single nucleotide changes: in particular, mutations at positions 1762 and 1764 were not associated with altered expression of viral proteins or with increased levels of viral replication, as also observed by Takahashi et al. (41) in chronic hepatitis patients. More recently, Sterneck et al. (39) suggested that viral variants with enhanced replication competence and/or a defect in HBeAg expression contribute to the pathogenesis of some FHB cases, though additional viral or host factors should also be considered in most cases.

One remarkable feature of this outbreak is the high case fatality rate (81.8%), which is unusual for acute HBV infection (26), although a similarly high rate has been observed in other nosocomial HBV outbreaks (17, 28, 42). The presence of the G-to-A mutation at nucleotide 1896 accounts for the anti-HBe status of the HR patient and for the absence or transient presence of circulating HBeAg in the newly infected patients. The presence of weak though detectable reactivity for HBeAg in some cases is not unexpected (28). Indeed, the presence of HBeAg in the serum of cases with fulminant and chronic HBV infection with no detectable wild-type precore sequences has been previously reported (21, 36, 38). However, cloning of amplified DNA from the HR patient and the case patients did not yield a minor population of wild-type virus expressing the HBe protein. The possible role of mutations in the core promoter sequence of the HBV genome in the pathogenesis of fulminant hepatitis is a controversial issue. In our study, we detected point mutations in the core promoter and in the precore regions of all viral isolates, leading to altered expression of HBe protein. However, the viral replication levels detected in vivo by hybridization and PCR assays were similar to those revealed in unrelated cases of self-limiting acute hepatitis B (data not shown). Stuyver et al. (40) recently reported on three cases of subfulminant hepatitis B among heart-transplanted patients: they suggest that additional amino acid changes located in residues 60 to 90 of the C ORF (a motif containing much of the HBcAg-related antigenicity) could affect the antigenic properties of the core protein. We detected a mutation at codon 67 (T-to-N/S) in all isolates from case patients and the source patient, together with a few other amino acid changes randomly distributed within the C ORF, which would not affect the putative capability of viral particles to present modified T-cell epitopes. Since mutations in the core region were previously described in cases with an aggressive course of acute hepatitis B (8), we believe that further experimental evidence is needed of the putative role of these mutations in the pathogenesis of FHB.

Indeed, the lack of induction of a tolerance phase in the absence of HBeAg secretion (leading to an accumulation of intrahepatic viral particles harboring mutated HBcAg, which are massively attacked by cytotoxic T lymphocytes) is contradicted by the evidence of FHB cases infected with wild-type precore viruses (10, 24, 27). In the viral isolates from all cases, we also detected nucleotide substitutions (and predicted amino acid changes) randomly distributed within the other viral ORFs. However, none of these mutations was located within structurally and antigenically essential motifs. These data confirm previous observations indicating that neither severity nor outcome of infection is influenced by any additional mutation in the HBV genome (19). Since it is conceivable that HBV is not directly cytopathic, other nonviral factors may be responsible for an aggressive course of infection. These host factors may include altered immune response to specific viral epitopes, the HLA environment of hosts where immunosuppressive therapy is being administered or has been withdrawn, and finally, the underlying severe disease affecting the HBV-infected patients. While further study of the particular HBV-host interplay in patients with hematologic disorders is clearly necessary, the present data do not support the hypothesis that viral factors alone were involved in the tragic clinical outcome of these cases.

This is one of the largest hospital-acquired hepatitis B outbreaks in the literature, with an extremely high case fatality rate. However, had the case fatality rate been lower, the spread of HBV among patients might have gone unnoticed. Similar episodes with wild viruses may occur more often than is currently recognized, leading to chronic disease and delayed mortality. The findings of this study strongly warrant efforts to increase personnel awareness of blood-borne infections in hematology facilities, to ensure that standard precautions are taken and to restrict the use of multidose vials. Moreover, patients receiving treatment for hematologic and oncologic diseases should be given a vaccination against HBV, which in Italy is free to all immunosuppressed patients (31).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by Istituto Superiore di Sanità (target project “Epatiti virali”) and Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche (target project “Biotechnology”). The epidemiologic investigation was conducted as part of Ricerca Corrente of IRCCS “Spallanzani.”

We are grateful to Y. Hutin and the Hepatitis Branch of the Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Ga., for contributing to the generation of hypotheses and for reviewing the manuscript and to E. Girardi and P. Pezzotti for their assistance in statistical analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allander T, Gruber A, Naghavi M, Beyene A, Soderstrom T, Bjorkholm M, Grillner L, Persson M A. Frequent patient-to-patient transmission of hepatitis C virus in a haematology ward. Lancet. 1995;345:603–607. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90518-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alter M J, Ahtone J, Maynard J E. Hepatitis B virus transmission associated with a multiple-dose vial in a hemodialysis unit. Ann Intern Med. 1983;99:330–333. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-99-3-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alter M J, Favero M S, Maynard J E. Impact of infection control strategies on the incidence of dialysis-associated hepatitis in the United States. J Infect Dis. 1986;153:1149–1151. doi: 10.1093/infdis/153.6.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aye T T, Uchida T, Becker S O, Hirashima M, Shikata T, Komine F, Moriyama M, Arakawa Y, Mima S, Mizokami M. Variations of hepatitis B virus precore/core gene sequence in acute and fulminant hepatitis B. Dig Dis Sci. 1994;39:1281–1287. doi: 10.1007/BF02093794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baumert T F, Marrone A, Vergalla J, Liang T J. Naturally occurring mutations define a novel function of the hepatitis B virus core promoter in core protein expression. J Virol. 1998;72:6785–6795. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.8.6785-6795.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baumert T F, Rogers S A, Hasegawa K, Liang T J. Two core promoter mutations identified in a hepatitis B virus strain associated with fulminant hepatitis result in enhanced viral replication. J Clin Investig. 1996;98:2268–2276. doi: 10.1172/JCI119037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carman W F, Fagan E A, Hadziyannis S, Karayiannis P, Tassopoulos N C, Williams R, Thomas H C. Association of a precore genomic variant of hepatitis B virus with fulminant hepatitis. Hepatology. 1991;14:219–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ehata T, Omata M, Chuang W L, Yokosuka O, Ito Y, Hosoda K, Ohto M. Mutations in core nucleotide sequence of hepatitis B virus correlate with fulminant and severe hepatitis. J Clin Investig. 1993;91:1206–1213. doi: 10.1172/JCI116281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ehrmann J, Kucerova L, Jezdinska V, Papajik T, Galuszova T, Dusek J, Indrak K. Fulminant hepatitis caused by a hepatitis B virus infection in patients with haematologic malignancies. Report of 5 cases. Acta Univ Palacki Olomuc Fac Med. 1996;140:81–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feray C, Gigou M, Samuel D, Bernuau J, Bismuth H, Brechot C. Low prevalence of precore mutations in hepatitis B virus DNA in fulminant hepatitis type B in France. J Hepatol. 1993;18:119–122. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(05)80019-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gunther S, Piwon N, Iwanska A, Schilling R, Meisel H, Will H. Type, prevalence, and significance of core promoter/enhancer II mutations in hepatitis B viruses from immunosuppressed patients with severe liver disease. J Virol. 1996;70:8318–8331. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.12.8318-8331.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hadler S C, Doto I L, Maynard J E, Smith J, Clark B, Mosley J, Eickhoff T, Himmelsbach C K, Cole W R. Occupational risk of hepatitis B infection in hospital workers. Infect Control. 1985;6:24–31. doi: 10.1017/s0195941700062457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hardie D R, Kannemeyer J, Stannard L M. DNA single strand conformation polymorphism identifies five defined strains of hepatitis B virus (HBV) during an outbreak of HBV infection in an oncology unit. J Med Virol. 1996;49:49–54. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9071(199605)49:1<49::AID-JMV8>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harpaz R, Von Seidlein L, Averhoff F M, Tormey M P, Sinha S D, Kotsopoulou K, Lambert S B, Robertson B H, Cherry J D, Shapiro C N. Transmission of hepatitis B virus to multiple patients from a surgeon without evidence of inadequate infection control [see comments] N Engl J Med. 1996;334:549–554. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199602293340901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hasegawa K, Huang J, Rogers S A, Blum H E, Liang T J. Enhanced replication of a hepatitis B virus mutant associated with an epidemic of fulminant hepatitis. J Virol. 1994;68:1651–1659. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.3.1651-1659.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hlady W G, Hopkins R S, Ogilby T E, Allen S T. Patient-to-patient transmission of hepatitis B in a dermatology practice. Am J Public Health. 1993;83:1689–1693. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.12.1689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hutin Y J, Goldstein S T, Varma J K, O'Dair J B, Mast E E, Shapiro C N, Alter M J. An outbreak of hospital-acquired hepatitis B virus infection among patients receiving chronic hemodialysis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1999;20:731–735. doi: 10.1086/501573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaneko M, Uchida T, Moriyama M, Arakawa Y, Shikata T, Gotoh K, Mima S. Probable implication of mutations of the X open reading frame in the onset of fulminant hepatitis B. J Med Virol. 1995;47:204–208. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890470304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karayiannis P, Alexopoulou A, Hadziyannis S, Thursz M, Watts R, Seito S, Thomas H C. Fulminant hepatitis associated with hepatitis B virus e antigen-negative infection: importance of host factors. Hepatology. 1995;22:1628–1634. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kidd-Ljunggren K, Broman E, Ekvall H, Gustavsson O. Nosocomial transmission of hepatitis B virus infection through multiple-dose vials. J Hosp Infect. 1999;43:57–62. doi: 10.1053/jhin.1999.0607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kosaka Y, Takase K, Kojima M, Shimizu M, Inoue K, Yoshiba M, Tanaka S, Akahane Y, Okamoto H, Tsuda F, et al. Fulminant hepatitis B: induction by hepatitis B virus mutants defective in the precore region and incapable of encoding e antigen. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:1087–1094. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90286-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumagai K, Takagi T, Sakai C, Oguro M, Kawai S, Nakahori S, Yokosuka O, Ohtoh M. A fatal case of a hepatitis B virus carrier with fulminant hepatic failure after cytotoxic chemotherapy for malignant lymphoma. Rinsho Ketsueki. 1993;34:1587–1589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lanphear B P, Linnemann C C, Jr, Cannon C G, DeRonde M M. Decline of clinical hepatitis B in workers at a general hospital: relation to increasing vaccine-induced immunity. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;16:10–14. doi: 10.1093/clinids/16.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laskus T, Persing D H, Nowicki M J, Mosley J W, Rakela J. Nucleotide sequence analysis of the precore region in patients with fulminant hepatitis B in the United States. Gastroenterology. 1993;105:1173–1178. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90964-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laskus T, Rakela J, Nowicki M J, Persing D H. Hepatitis B virus core promoter sequence analysis in fulminant and chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:1618–1623. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90651-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee W M. Acute liver failure. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1862. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312163292508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liang T J, Hasegawa K, Munoz S J, Shapiro C N, Yoffe B, McMahon B J, Feng C, Bei H, Alter M J, Dienstag J L. Hepatitis B virus precore mutation and fulminant hepatitis in the United States. A polymerase chain reaction-based assay for the detection of specific mutation. J Clin Investig. 1994;93:550–555. doi: 10.1172/JCI117006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liang T J, Hasegawa K, Rimon N, Wands J R, Ben-Porath E. A hepatitis B virus mutant associated with an epidemic of fulminant hepatitis. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1705–1709. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199106133242405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manzin A, Bagnarelli P, Menzo S, Giostra F, Brugia M, Francesconi R, Bianchi F B, Clementi M. Quantitation of hepatitis C virus genome molecules in plasma samples. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1939–1944. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.8.1939-1944.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meyer R A, Duffy M C. Spontaneous reactivation of chronic hepatitis B infection leading to fulminant hepatic failure. Report of two cases and review of the literature. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1993;17:231–234. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199310000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ministero della Sanità. Protocollo per l'esecuzlone della vaccinazione contro l'epatite B. D.M. 22 December 1997.

- 32.Naoumov N V, Petrova E P, Thomas M G, Williams R. Presence of a newly described human DNA virus (TTV) in patients with liver disease. Lancet. 1998;352:195–197. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)04069-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Omata M, Ehata T, Yokosuka O, Hosoda K, Ohto M. Mutations in the precore region of hepatitis B virus DNA in patients with fulminant and severe hepatitis. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1699–1704. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199106133242404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oren I, Hershow R C, Ben-Porath E, Krivoy N, Goldstein N, Rishpon S, Shouval D, Hadler S C, Alter M J, Maynard J E, et al. A common-source outbreak of fulminant hepatitis B in a hospital. Ann Intern Med. 1989;110:691–698. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-110-9-691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pollicino T, Zanetti A R, Cacciola I, Petit M A, Smedile A, Campo S, Sagliocca L, Pasquali M, Tanzi E, Longo G, Raimondo G. Pre-S2 defective hepatitis B virus infection in patients with fulminant hepatitis. Hepatology. 1997;26:495–499. doi: 10.1002/hep.510260235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sato S, Suzuki K, Akahane Y, Akamatsu K, Akiyama K, Yunomura K, Tsuda F, Tanaka T, Okamoto H, Miyakawa Y, et al. Hepatitis B virus strains with mutations in the core promoter in patients with fulminant hepatitis. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122:241–248. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-122-4-199502150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Soh L T, Ang P T, Sng I, Chua E J, Ong Y W. Fulminant hepatic failure in non-Hodgkin lymphoma patients treated with chemotherapy. Eur J Cancer. 1992;28A:1338–1339. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(92)90513-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sterneck M, Gunther S, Santantonio T, Fischer L, Broelsch C E, Greten H, Will H. Hepatitis B virus genomes of patients with fulminant hepatitis do not share a specific mutation. Hepatology. 1996;24:300–306. doi: 10.1002/hep.510240203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sterneck M, Kalinina T, Gunther S, Fischer L, Santantonio T, Greten H, Will H. Functional analysis of HBV genomes from patients with fulminant hepatitis. Hepatology. 1998;28:1390–1397. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stuyver L, De Gendt S, Cadranel J F, Van Geyt C, Van Reybroeck G, Dorent R, Gandjbachkh I, Rosenheim M, Charlotte F, Opolon P, Huraux J M, Lunel F. Three cases of severe subfulminant hepatitis in heart-transplanted patients after nosocomial transmission of a mutant hepatitis B virus. Hepatology. 1999;29:1876–1883. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takahashi K, Ohta M, Kanai K, Akahane Y, Iwasa Y, Hino K, Ohno N, Yoshizawa H, Mishiro S. Clinical implications of mutations C-to-T1653 and T-to-C/A/G1753 of hepatitis B virus genotype C genome in chronic liver disease. Arch Virol. 1999;144:1299–1308. doi: 10.1007/s007050050588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tanaka S, Yoshiba M, Iino S, Fukuda M, Nakao H, Tsuda F, Okamoto H, Miyakawa Y, Mayumi M. A common-source outbreak of fulminant hepatitis B in hemodialysis patients induced by precore mutant. Kidney Int. 1995;48:1972–1978. doi: 10.1038/ki.1995.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.The Incident Investigation Teams and others. 1997. Transmission of hepatitis B to patients from four infected surgeons without hepatitis B e antigen. N. Engl. J. Med. 336:178–184. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Yoshiba M, Okamoto H, Mishiro S. Detection of the GBV-C hepatitis virus genome in serum from patients with fulminant hepatitis of unknown aetiology. Lancet. 1995;346:1131–1132. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91802-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yoshiba M, Sekiyama K, Iwabuchi S, Takatori M, Tanaka Y, Uchikoshi T, Okamoto H, Inoue K, Sugata F. Recurrent fulminant hepatic failure in an HB carrier after intensive chemotherapy. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:1751–1755. doi: 10.1007/BF01303187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]