Abstract

Auriculotherapy, the treatment of patients using ear-point stimulation, is a French technique, deeply rooted in a European medical tradition. Although the French physician, Paul Nogier, MD (1908–1996 ad) invented and promoted auriculotherapy, it is nevertheless worth mentioning, in the course of European history, the occasional use of the ear to relieve head, face, or sciatic nerve pain. It took several centuries to find a physician who attempted to understand why some healers obtained interesting therapeutic results with ear-point stimulation. The exact history of auriculotherapy remained a mystery for a long time. Only recently have researchers begun to understand it better. Many articles, admittedly not based on robust data, wrongly ascribed the discovery of auricular somatotopy to ancient civilizations. It was the recent reading of a book on the treatment of sciatica written in 1869 by Lagrelette that enabled the current author of this article to characterize and confirm the Western roots of auriculotherapy through the history of cauterizations.

Keywords: Ear cauterization, ear acupuncture, Nogier frequencies, auriculo-cardiac reflex (RAC), radial pulse, auricular cartographies

INTRODUCTION

Auriculotherapy has its roots in the distant past. Hippocrates (460–380 bc) can be regarded as the unwitting inventor of this method. He even recommended cauterizations as a treatment for some pathologies. In one of his last aphorisms, he explicitly stated that pathologies that could not be cured by means of medicine could be cured surgically; those impossible to cure surgically could be cured by fire (cauterizations) and those impossible to cure by fire could not be cured at all (cited in Romoli et al. Aphorisms, section VII, no.87).1

Hippocrates considered cauterization to be at forefront of the therapeutic armamentarium and that this approach was therefore the ideal therapy when all other treatments had failed. Since the time of Hippocrates, cauterization had become a common therapeutic technique and integral to medical teaching as well. This practice occurs throughout the entire history of medicine. During the Middle Ages, in tenth-century Cordoba in Muslim Spain, Albucasis used the cauterization technique.2 In the sixteenth century, Paré also described the use of cauterization to stop bleeding or hemorrhaging.3 In the nineteenth century, many physicians used cauterization within the Mediterranean area. Percy, the chief surgeon under Napoleon, used cauterization on the battlefield.4

There were many therapeutic indications for cauterization, including: hemostasis; wound cleaning; and abscess treatment. In addition, cauterizations were also used to relieve pain. In this case, cauterization was applied loco dolenti (on the pain site). For example, shoulder pain was treated by cauterization in the shoulder area and hip pain was treated by cauterization in the hip area.

Hippocrates stated: “Persistent, permanent pain in some part of the body which had resisted all other available means of treatment, required cauterization.” In the case of sciatica, his advice was to “burn raw linen where the pain was felt.”5

Various Cauterization Techniques for Sciatic-Nerve Pain

According to Cotugno, in the seventh century, Paul of Aegina—who was very experienced in the treatment of sciatica by cauterization—used to recommend cauterization of a point just above the ankle. According to Zecchius, it was necessary to apply the cautery slightly lower than the knee, on the lateral aspect of the painful side.6

In La Chirurgie d'Albucasis (translation by Leclerc, in Paris in1861), it is mentioned that

cauterization should be performed three times at the hip level, using an olive-shaped cautery—with the three cauterizations applied in a triangle-shaped position. The distance between each cauterization should be as large as the thickness of a finger. Moreover, a cauterization should be performed on the articulation point, making a total of four. If the disease spreads to the thigh and leg, the thigh should be cauterized twice on the pain trajectory indicated by the patient, and a further cauterization should be performed four fingers above the calcaneal tendon.6

Cauterization was therefore performed on the pain site, but there were some exceptions, understandably for migraine, or for face or tooth neuralgia. Given that it was difficult, if not impossible to cauterize the head, cheek, or jaw, cauterization was performed in the area closest to the face or head—in other words, the ear. A cautery was applied to the highest part of the ear for migraine and to the back part of the ear for tooth pain. These procedures were confirmed by Valsalva,7 who was renowned for his research in anatomy, and who, during his dissections, noted many cauterization scars at the back of the ear, that had been performed by healers at that time to alleviate dental neuralgia.

Percy described in his book Pyrotechnie Chirurgicale Pratique (published in 1811), the method of cauterization of the antitragus for tooth pain.4 Ruys (Journal de Médecine et de Chirurgie Pratiques, 1851; cited by Lagrelette) noted in Les Archives Belges, that ear cauterization was a current practice in the Flemish countryside. A burgomaster's wife had shown him the instrument she had been using for 20 years to treat people in her household for severe toothache or face neuralgia. She had learned that secret from the village blacksmith, who had himself learned it from his ancestors.6

With reference to Hippocrates, it is easy to understand today why ear cauterization was performed for pain in the face or head. Nevertheless, it seems strange or even surprising to learn that, in seventeenth-century century Europe, ear cauterizations were performed to treat sciatica, which would appear illogical because the ear is not at all close to the lower limb. Bonetus (1682; cited by Lagrelette) noted:

To treat any kind of sciatica, I have seen some healers apply a cautery to burn the inner part of the ear where a fold of cartilage shows a kind of small tumour. Several of them were actually successful, the reason being that, in many cases of sciatica, a substance flows from the head which is intercepted when the ear is cauterized.6

One might well ask why ear cauterization was performed to treat sciatica. There is no answer. Perhaps, 1 day, a patient complaining of both migraine and sciatica happened to be relieved of the sciatica after an ear cauterization was performed to treat the migraine, and, later on, that same procedure was performed to treat sciatica. Sometimes, progress in medicine is made by pure chance.

Widespread Use of Cauterizations in France Throughout Many Centuries

For centuries, in France, healers performed ear cauterizations to treat sciatica, probably without medical authorities even knowing about it. A letter from Luciana from Bastia, Corsica, in the Journal des Connaissances Médico-Chirurgicales in May 1850, sounded the alarm, as he tried to warn medical circles about common practices among healers.8 In his letter, Luciana described the technique used by blacksmiths in Corsica to cure sciatica, whereby red-hot irons were used to cauterize a point on the outer ear, homolateral to the painful side.

That article had a great impact. Malgaigne of Paris, surprised by the Corsica healers' results, tried to perform cauterizations himself at the Saint-Louis Hospital and noticed the astounding efficacy of this procedure for treating sciatica to such an extent that he invited his colleagues to attend cauterization sessions.9 Brown-Séquard, the father of modern neurology and a worldwide renowned scientist, reported on this procedure in his opening lecture of The Medical Lectures of Harvard University, on November 7, 186610:

I can remember the loud laughter which shook the French medical world when it was announced that, for centuries, on the French island of Corsica, sciatica had been treated by the cauterization of the ear helix. But as a man of courage and an independent mind, Professor Malgaigne was able to recognise that sometimes the application of a red-white hot iron to the ear helix could cure sciatica.

According to Professor Brown-Séquard, recovery took place through a reflex pathway.

Malgaigne, a very open-minded and brilliant man, did not investigate ear cauterization further because one of his peers, the famous and influential Boulogne, openly expressed his reservations about this medical technique. All publications on the subject were brought to a standstill, and, for more than a century, ear cauterization as means of treating sciatica was no longer discussed in university circles.

Cauterizations in Italy

Keen interest in ear cauterizations became widespread; in Italy. Finco treated 48 patients and reported success with 30 patients, partial success with 10 patients, and no success with 8 patients.11

An Unconventional Physician in Lyon Inspired by a Healer in Marseille: The Discovery of Auricular Somatotopy: An Unconventional Physician in Lyon Inspired by a Healer in Marseille

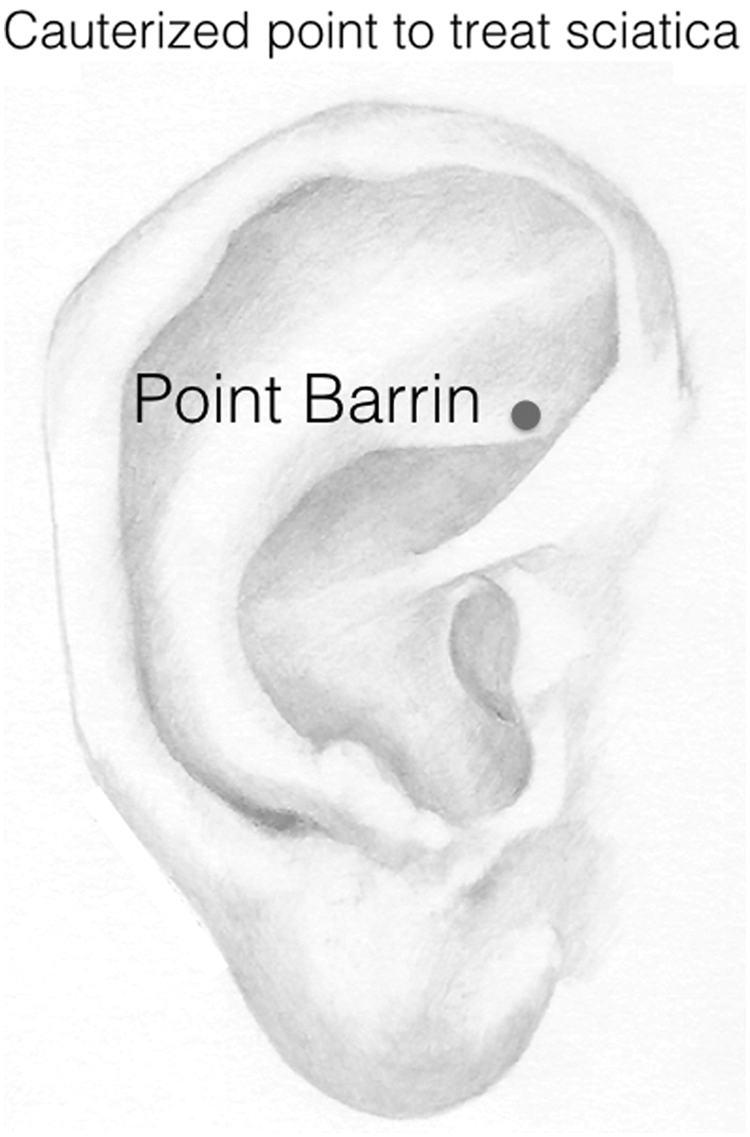

About a century later, in 1951, Dr. Paul Nogier, MD, a physician from Lyon, France, saw a patient who had a small, glistening red scar on the ear. This patient explained that he had been suffering from sciatica that had been resistant to all chemical treatments, and that he had totally recovered from it, thanks to a healer in Marseille, a Mrs. Barrin. Barrin's treatment consisted of cauterizing a point on his ear, using a white-hot metal rod (Fig. 1). Within a few hours, this patient was cured from pain for which no successful solution had been found prior.

FIG. 1.

Point used by Mrs. Barrin, a local healer, to treat sciatica.

A few weeks later, another patient, with a similar sort of scar on the ear, told the same story, adding that his pain had disappeared, thanks to this same woman in Marseille. On hearing these 2 patients' stories, Dr. Paul Nogier asked himself why and how this procedure of burning a point on the ear could cure sciatic-nerve pain. He subsequently developed a keen interest in ear pavilions.12

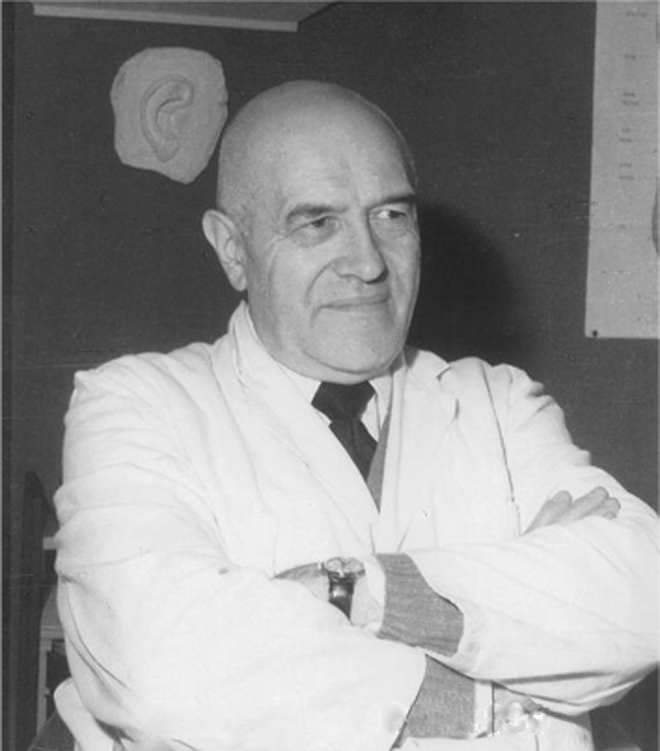

Dr. Paul Nogier was an unconventional physician. After leaving school, he did not choose to study medicine right away, but, instead, studied engineering for 3 years at the Ecole Centrale de Lyon. Following this, he studied medicine at Lyon University. This was where he discovered physiology, pathology, and all medical subjects, through the eyes of a physicist.13 At the time, medicine relied on chemistry, with the prevailing idea that a chemical treatment should correspond to each pathology (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Paul Nogier, MD (1908–1996 ad), Lyon, France.

However, Dr. Paul Nogier, and a few other like-minded physicians, approached things from a completely different perspective. For him, first and foremost, symptoms or disorders were the results of some sort of malfunction in the patient's body. It was therefore necessary to find the reason for the malfunction and to treat it, before treating the symptoms. This was also Bernard's approach: his teaching always underlined the importance of the functional nervous system in the occurrence of organic pathologies.14

Today, this may help readers understand why, at this period of his career and having finished his medical studies, Dr. Paul Nogier developed a keen interest in acupuncture and manual medicine; thus revealing a strong and independent mind for his time.

From 1951 onward, he started studying the ear, following the case histories of the patients treated by Barrin. He understood the point treated by this healer had never been described by Chinese acupuncturists who had never actually developed techniques using ear points.15 Having an experimental mindset himself, Dr. Paul Nogier tried the “Barrin point cauterization technique” to treat sciatic nerve pain. After achieving success with this, he tried to treat hip, knee, and shoulder pain with cauterization. He observed that cauterizing the particular ear point used by Barrin only cured sciatica. His hypothesis was that the Barrin point corresponded to the (L-5–S-1) lumbosacral area where the sciatic-nerve emerges.12

With that hypothesis as a starting point, he wondered whether the protruding part of the ear, the antihelix, could correspond to the entire spinal column. Gradually, he came to realize that the outer ear had exceptional reflex properties, and that each point in the ear pavilion was related to a specific part of the body. He observed that the human body was somewhat “sketched out on the ear” with: the lobule, at the bottom of the ear, corresponding to the head; the concha in the center, corresponding to the thorax and abdomen; and the cartilaginous portion, the antihelix, corresponding to the spinal column. The ear looked like an upside-down fetus.

Dr. Paul Nogier's Works on Auricular Reflex Therapy

To carry out his study, Dr. Paul Nogier used some very basic implements, such as a pressure probe that he designed himself, using a “ball-pen” tip from which he extracted the ink cartridge and connected the sharp end directly to a spring. This enabled him to look for the painful points of the ear, because he had noticed that, when a part of the body experienced pain, the corresponding ear point would also be painful when pressure was applied to it.12 He saw the ear as a sort of “control panel,” where one could look for painful points. Pressure probe in hand, he studied his patients' ears, looking for painful points that corresponded to the different parts of the body where his patients experienced pain.

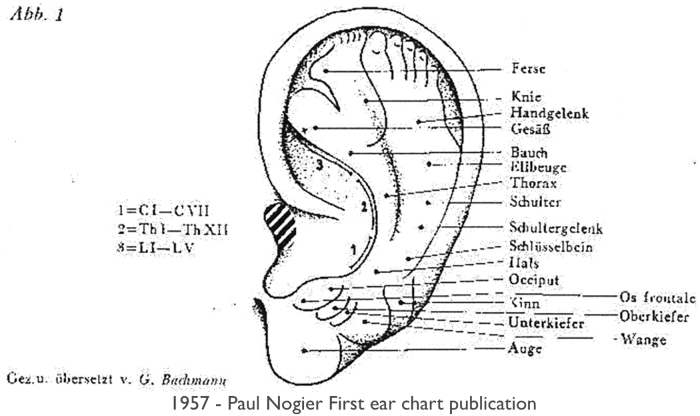

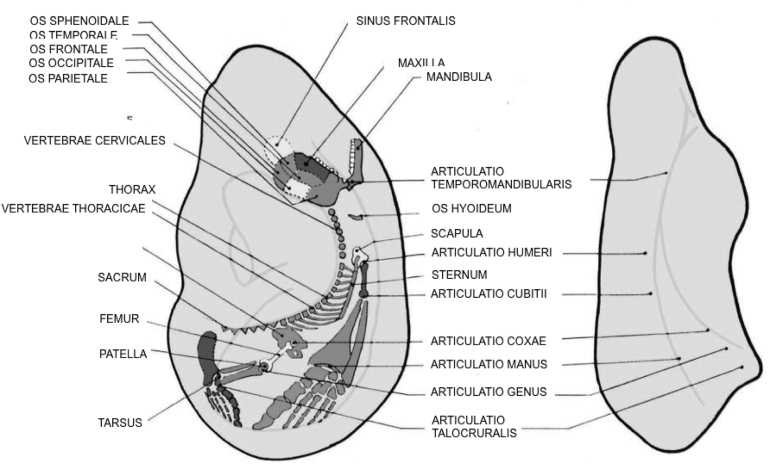

In this way, after 4 or 5 years of research, he was able to pinpoint on the ear the different areas that corresponded to the spinal column and the upper and lower limbs, and sketch a cartography of the ear. He published this first stage of his work in 1956. That article (cited by HOR Ting) was initially translated into German, and later published in the Chinese Shanghai Magazine, which introduced auriculotherapy accurately to mainland China.15,16 As a result of this article, Chinese acupuncturists developed ear acupuncture, which had not existed in China before (Fig. 3).15

FIG. 3.

First ear map by Paul Nogier, MD, in 1957 [in German]. Deutsche Zeitschrift für Akupunctur. 1957;VI:5–6.16

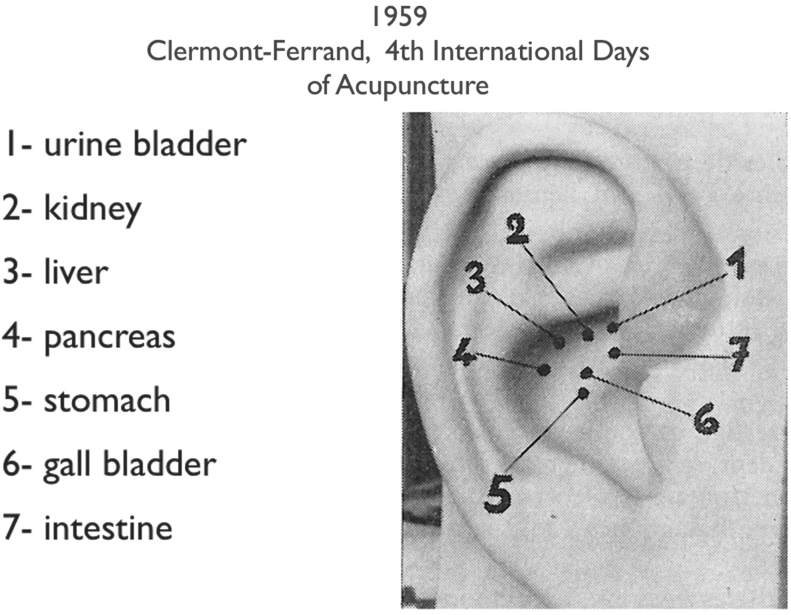

Until 1963, Dr. Paul Nogier continued his research, providing ever-more-accurate ear cartographies (Fig 4). However, he encountered a major obstacle when he tried to find points corresponding to organs on the auricle. In fact, only pain in the organs create painful points on the ear. Affected organs, when not painful, are not capable of generating painful information on the ear. Nevertheless, many organs, such as the thyroid, the adrenals, the liver, and the kidneys are hardly ever painful, even when they do not function properly. Thus, for this reason, Dr. Paul Nogier found it extremely difficult to finish his cartographies. He wrote:

first and foremost, in order to provide a tool for a reflex point identification, an ailing organ needs be clearly painful, with pain specific to that disorder, susceptible of being characterized by touch, pressure, movement or cold. In such circumstances, one should be able to detect a painful point on one of the ear pavilions.”17

FIG. 4.

1959, Paul Nogier, MD: Localizations of the superior concha. Presentation at the 4th International Days of Acupuncture, Clermont Ferrand, France.

The situation was resolved by the discoveries of a Frenchman, Niboyet. Niboyet discovered that the acupuncture points scattered over the body have specific electrical behaviors and could be detected by using electronic devices measuring the electrical resistance of the skin. Skin has lower electrical resistance on acupuncture points.18 Dr. Paul Nogier drew inspiration from Niboyet's findings and observed that points with low electrical resistance also exist on the ear. Thanks to these findings, he was able to locate the positions of organs on the ear.

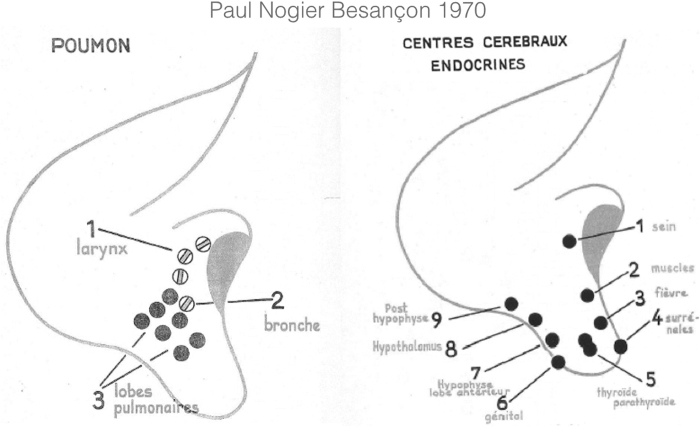

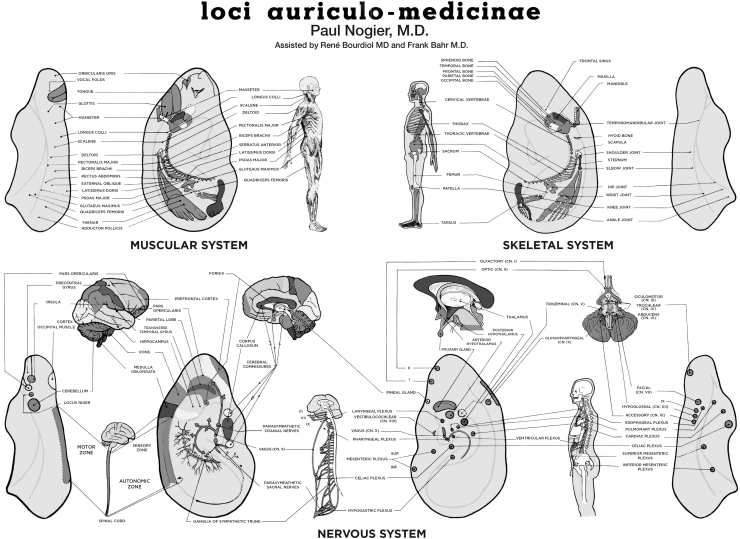

Today, it is known that there are 2 different types of points on the ear. Some points are painful when there is peripheral pain. Other points are electrically perturbed when the corresponding organ does not function correctly.19,20 Ear scanning, using a very simple pressure probe and a device measuring resistance, can find either painful points or electrically perturbed points, and provide a fairly accurate idea of the pathologies present, and indicate whether they are organic or functional. After several years of observation, Dr. Paul Nogier refined his research and published extremely precise cartographies showing the locations of different body-parts on the external ear (Figs. 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10). This is the foundation of auriculotherapy.21–25 In 1969, Dr. Paul Nogier published the first book on this method entitled Le Traité d'Auriculothérapie (Treatise of Auriculotherapy).21

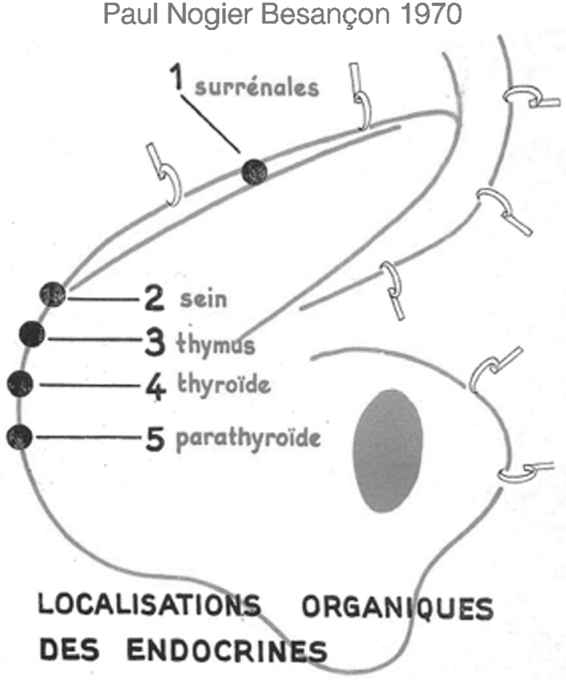

FIG. 5.

Paul Nogier, MD. Localisations of the inferior concha. Presentation at the 7th International Days of Acupuncture (VIIès Journées d'Acupuncture, d'Auriculothérapie et de Médecine Manuelle), Besançon, France, September 15–20, 1970.

FIG. 6.

Paul Nogier, MD. Localisations of the endocrine glands. Presentation at the 7th International Days of Acupuncture VIIès Journées d'Acupuncture, d'Auriculothérapie et de Médecine Manuelle, Besançon, France, September 15–20, 1970.

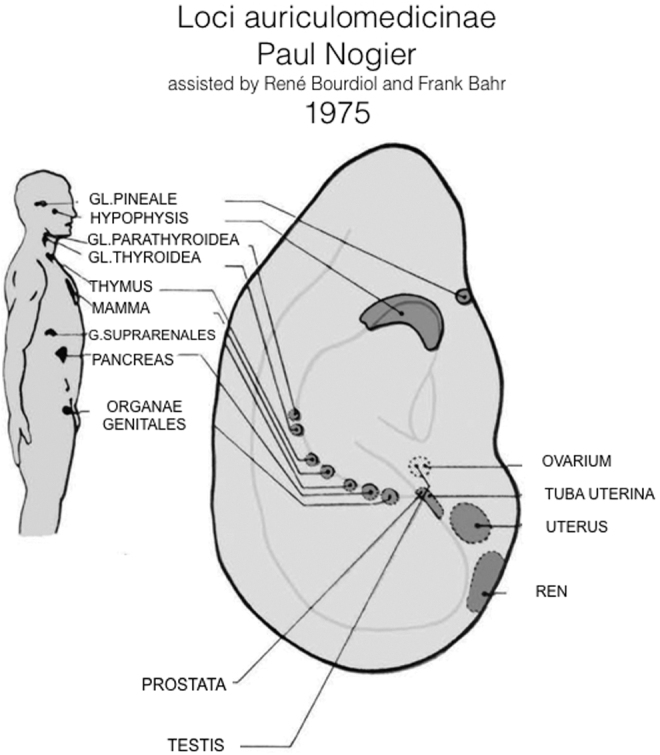

FIG. 7.

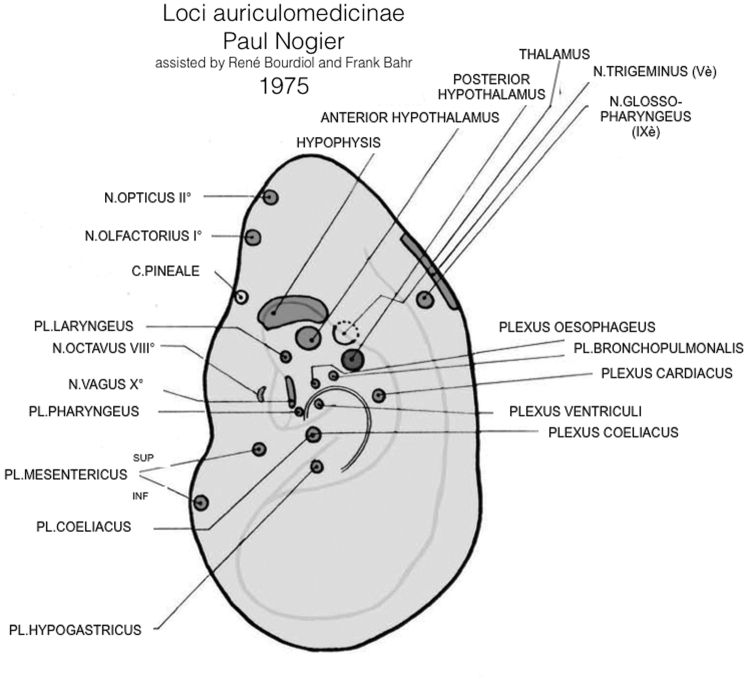

Loci auriculomedicinae, 1975, [in latin]. Paul Nogier, MD, was the creator of this very precise ear map. The drawings were made by René Bourdiol. Frank Bahr, MD, participated as an assistant.

FIG. 8.

Loci auriculomedicinae [in French], 1975: Muskuloskeletal system.

FIG. 9.

Loci auriculomedicinae [in latin], 1975: Nervous system.

FIG. 10.

Loci auriculomedicinae [in latin] 1975: Endocrine glands.

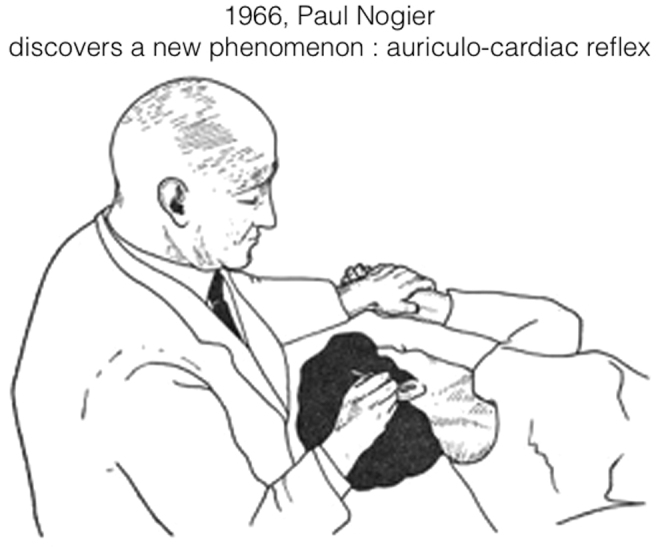

Auriculotherapy and the Radial Pulse

In 1966, during his research, Dr. Paul Nogier discovered a new phenomenon which he called the RAC (réflexe auriculo cardiaque), or auriculo-cardiac reflex.21,26 He noticed that, when one applies pressure on certain ear points, the radial pulse is temporarily distorted (Fig. 11). Cardiac rythm remains unchanged, but the pulse becomes harder or softer for 2 or 3 pulsations. This arterial phenomenon—which is delicate and barely observable, something that can be perceived manually on the radial artery—was subsequently termed the vascular autonomic signal (VAS; le signal vasculaire). Clearly, a great deal of time and practice are necessary to observe these minimal variations in pulse.

FIG. 11.

In 1966, Paul Nogier, MD, discovers a new phenomenon, the auriculo-cardiac reflex. (Nogier P. Treatise of Auriculotherapy. Moulins-lès-Metz: Maisonneuve; 196921).

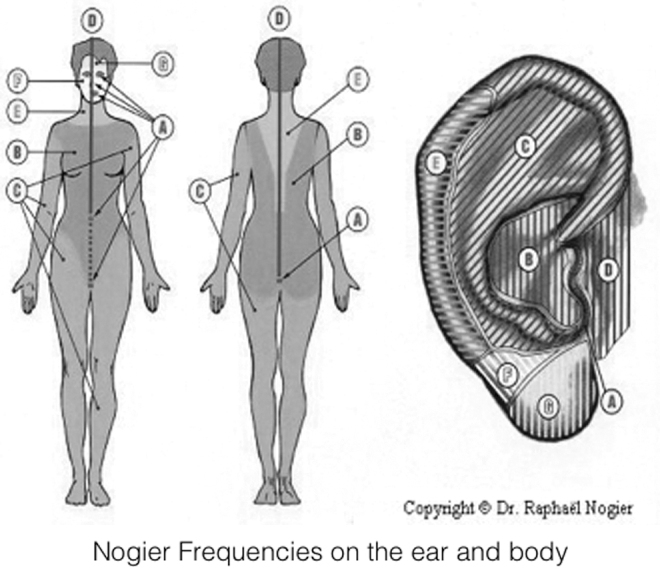

This unusual discovery prompted Dr. Paul Nogier to study the effects of numerous stimulations on the ear. When taking a patient's pulse while looking for the vascular signal, he stimulated different areas of the patient's ear using digital palpations, vibrations, or sound waves. His main focus, however, was the action of electromagnetic waves. Using increasingly sophisticated devices, he sought to understand why certain electromagnetic waves projected onto the ear triggered vascular signals while others did not. He realized that ear points are sensitive to different frequencies and that, by using precise electronic frequency output devices, one could stimulate precise functions.

Dr. Paul Nogier's approach was a very novel one, inasmuch as one can divide the surface of the ear into 7 clearly defined zones that are sensitive to 7 different types of frequencies.21 In this fashion, Dr. Paul Nogier was able to study the properties of the frequencies he had discovered using the vascular signal (Fig 12).13,27,28

Frequency A (2.28 Hz) stimulates the cellular working mechanism. This frequency is used to treat inflammatory and degenerative pathologies.

Frequency B (4.56 Hz) stimulates multicellular functions, such as cohesion, coherence, and cell recognition. This frequency is used to treat disorders related to nutrition, the digestive system, and immunity (allergies and autoimmune pathologies).

Frequency C (9.12 Hz) stimulates muscle contraction and is used for spasms, sphincter dysfunction, and Parkinson's disease.

Frequency D stimulates symmetry (18.4 Hz) and is used primarily for locomotion dysfunctions.

Frequency E stimulates activity of the spinal cord (36.5 Hz) and is used for painful disorders and for certain spinal-cord diseases.

Frequency F (73 Hz) stimulates the subcortex. This frequency is widely used for treating eating disorders, endocrine disorders, menstrual and menstrual-cycle disorders, and problems related to menopause.

Frequency G (146 Hz) stimulates the cortex and helps treat psychosomatic disorders.

Today there are 8 different frequencies. an additional frequency, frequency Laterality (276 Hz), has been identified. It works on problems associated with laterality, and on learning disorders, such as dyslexia, dysorthography, dyscalculia, and stuttering.

Frequencies Used to Treat Ear-Points

Dr. Paul Nogier conducted research on this subject for many years. With his team of enthusiastic practitioners, he laid the foundations for a new method. While taking a patient's pulse, the physician projects colored lights, which have very specific frequencies, onto the ear, and observes which frequencies elicit a signal. First, this technique is a diagnostic tool. Second, it indicates methods of treatment. This is the reason that the term auriculomedicine was used to describe this method.27 Dr. Paul Nogier later objected to the use of this simplistic term because he noted that the vascular signal could be triggered by cutaneous stimulations outside the ear or by emotional stimulations.

DISCUSSION

Auriculotherapy: A Medical Procedure

Needless to say, auriculotherapy is no panacea. When practicing auriculotherapy, it is wrong to neglect or underestimate academic biomedical practice. Auriculotherapy practitioners perform rigorous clinical examinations of their patients and always revert back to the bases of the medical profession: discussion with each patient; patient examination; palpation; percussion; and auscultation. The techniques developed by Dr. Paul Nogier are far from being opposed to biomedical tradition and are merely a continuation of the works of nineteenth century medical semiologists. Nevertheless, the techniques require numerous biology and biochemistry studies to be validated scientifically.

As his research progressed quickly, Dr. Paul Nogier offered many novel ideas that varied in quality—and some were even contradictory. He spent more than 40 years of research, going backward and forward to develop his method.

Some of Dr. Paul Nogier's students—including Marignan,29 Rouxeville,30 de Sousa, and Vulliez—worked hard to streamline his work to highlight his major discoveries, and to steer auriculotherapy toward scientific validation. Marignan (from Aubagne, southern France)—a trained scientist and member of the Centre National de Recherche Scientific (CNRS; French National Center for Scientific Research)—worked on fundamental subjects, such as ear thermography and VAS graphic recordings.29 He was able to demonstrate that, when some parts of the body are warmed—such as the arm for example—spots on the ear show a significant decrease in temperature, while others, on the contrary, show an increase in temperature.

This apparent paradox may be explained by the role of the ear pavilion in the thermoregulation of the body. De Sousa developed fascinating theories about vascular signal hemodynamics; and Vulliez, a stomatologist, carried out a great deal of research on the vascular signal and frequencies.

In 2009, Terral (Montpellier, southern France) published an excellent book about ear points and body acupuncture points.31 She was able to demonstrate the physical existence of ear points, which are now called neurovascular bundles. These bundles, studied histologically by Senelar and Auziech, appear to be involved in the thermoregulation of the body.32,33 The ear pavilion is reportedly packed with small “probes” involved in control of organ thermoregulation. These bundles vary in size according to the different areas of the ear.32

Functional Disorders and Auriculotherapy

It is important to distinguish between functional disorders and organic disorders. An organic disorder occurs when an organ in the body shows anatomical lesions. A functional occurs in the absence of visible lesions and with an organ that does not function properly. Approximately 80% of medical consultations are related to functional disorders. These disorders stem from the autonomic nervous system. Biomedicine is ill-equipped to handle such disorders and can merely resort to prescribing drugs to alleviate a patient's complaints, without decreasing the disorder.

Some reflex therapies have proved very effective for modifying and regulating organ activity. They include acupuncture, auriculotherapy, manual medicine, and physiotherapy. The positive effects of these simple—and almost nonharmful—techniques may be explained by the incredible proprieties of the skin. Several physicians such as Jarricot, Head, Niboyet, and, of course Dr. Paul Nogier understood that, when an organ does not function properly, the physical characteristics of the skin are altered. Multiple nervous connections link the skin surface to the viscera.

On the surface of the skin, one can look for painful points, thickenings, pigmentation alterations, perturbed electric conductivity, and perturbed photo-perception. Therefore, the vascular signal is a tool to identify the dysfunction of some organs and then to treat them by pricking, massaging, or stimulating them with colored lights or other methods. The skin is a mirror image of the organs, and its detailed study provides very valuable pieces of information. Such is the principle of reflex therapies.18,34

CONCLUSIONS

In 1951, when, Dr. Paul Nogier observed sciatica cured by ear cauterization, he started carrying out scientific research on the ear pavilion. Inspired by a technique that healers were the only ones using, he was able to develop a method based on 3 crucial discoveries: (1) ear somatotopy; the VAS; and (3) stimulation frequencies.

In 1990, in Lyon, France, the World Health Organization set up a Working Group for the standardization of ear-points nomenclature.35 This important meeting was following 2 other meetings, one in Seoul (South Korea) in 1987, the other in Geneva (Switzerland) in 1989. Forty years after Dr. Paul Nogier's initial findings, auriculotherapy had finally achieved international recognition (Fig. 13).

FIG. 13.

1990, World Health Organization (WHO) meeting in Lyon, France, on the ear points nomenclature.35 Hiroshi Nakajima, MD, General Director of the WHO, Paul Nogier, MD, were both present at this meeting.

FIG. 12.

Representation of Nogier frequencies on the ear and on the body. In: Nogier R. Practical Introduction to Auriculomedicine [in French]. Boston: Haug; 1993.28

AUTHOR DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No financial conflicts of interest exist.

FUNDING INFORMATION

No funding was raised to finance this article.

REFERENCES

- 1. Romoli M, Rabischong P, Puglisi F, eds. Auricular Acupuncture Diagnosis. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Albucasis. On Surgery and Instruments [in Persian]. London: Wellcome Institute of the History of Medicine; reprinted; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Paré A. Works by Ambroise Paré [in French]. Paris: J-B Baillière; 1633. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Percy PF. How to Apply Fire in Surgery [in French; texte intégral (archive)]. Paris: Chez Méquignon l'aîne, Père, Libraire de la Faculté de Médecine; 1811. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Diderot D, le Rond d'Alembert J. Encyclopedia or a Systematic Dictionary of the Sciences, Arts, and Crafts, vol. 39 [In French]. Paris: National Library of France; circa 1772:578. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lagrelette PA. On the Studies of Sciatica, Historic, Semilogical and Treatment. Paris: Victor Masson et Fils, 1869. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Valsalva AM. The Treatment of the Human Ear [in Latin]. Bologna: Constantino Pisari; 1704. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Luciana. Ear cauterisation as effective sciatica treatment. J Connaissances Médico-Chirurgicales.; 1850; 9. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Malgaigne J. Sciatica: Ear cauterization [in French]. Gaz des Hôp. 1850;421:410. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brown-Séquard CE. Cauterization of the Ear [keynote speech to medical students of Harvard University on November 7, 1866; in French]. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Finco J. Ear cauterisation [In French]. Lombardy Gazette. 1860;37(39):41. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nogier P. Pinna: Reflex zones and points [in French]. Bull Soc Acupunct. 1956;20. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nogier P, Nogier R. The Man in the Ear. Moulins-lès-Metz: Maisonneuve; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bernard C. Introduction to Experimental Medicine. Paris: J-B Baillière et Fils; 1865.14. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ting H. Auriculotherapy: A French creation, independent of acupuncture. Acupunct Moxib. 2016;15(3):243–245. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nogier P. [in German]. Über die Akupunktur der Ohrmuschel von Paul Nogier. Deutsche Zeitschrift für Akupunctur. 1957;4:5–6. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nogier P. Visceral projections in the concha [presentation]. VIIès Journées d'Acupuncture, d'Auriculothérapie et de Médecine Manuelle. Besançon, France, September 15–20, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Niboyet JEH. Low resistivity of punctiform cutaneous surface consistent with points and meridians. Basis of acupuncture. In: Thesis of Science: Marseille, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nogier R. Auriculotherapy. Le Touvet, France: Ambre; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nogier R. Are the electrically detectable auricular points always painful? [presentation] VIIth International Symposium of Auriculotherapy, Lyon, France, August 6–8, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nogier P. Treatise of Auriculotherapy. Moulins-lès-Metz: Maisonneuve; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nogier P. Auriculotherapy [in French]. Lyon-Méditerranée Médical. 1971;7(14):1311–1319. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nogier P. Handbook of Auriculotherapy. Moulins-lès-Metz: Maisonneuve; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nogier P, with Bourdiol R, Bahr F. Loci Auriculomedicinae. Moulins-lès-Metz: Maisonneuve; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bourdiol R. Elements of Auriculothérapy. Moulins-lès-Metz: Maisonneuve; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nogier P. From Auriculotherapy to Auricular Medicine. Moulins-lès-Metz: Maisonneuve; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nogier R. Health and Pinna. Coral Gables, FL: Mango; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nogier R. Practical Introduction to Auriculomedicine [in French]. Boston: Haug; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Marignan M. Ear Thermography: Lyons: Groupe Lyonnais d'Etudes Médicales (GLEM); 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rouxeville Y. The keys of auriculotherapy; Clinic and practice [in French]. Molenbeeck-Saint Jean, Belgium: Satas; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Terral C. Pain and Acupuncture. Montpellier, France: Sauramps Médical; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Auziech O. Histological Study of Lower Resistivity Points and Their Possible Actions in Acupuncture. Montpellier, France: Sauramps Médical; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Senelar R, Auziech O. Histophysiology of the acupuncture point and Traditional Chinese Medicine. Encyclopédie de Med Nat. Paris; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bossy J. Neurological Basis of Reflexotherapies. Paris: Masson; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 35. World Health Organization. Report on the Working Group on Auricular Acupuncture Nomenclature. Lyon; 1990. [Google Scholar]