Abstract

Virtual communities of practice (VCoPs) facilitate distance learning and mentorship by engaging members around shared knowledge and experiences related to a central interest. The American College of Emergency Physicians and Emergency Medicine Residents’ Association's Global Emergency Medicine Student Leadership Program (GEM‐SLP) provides a valuable model for building a VCoP for GEM and other niche areas of interest. This VCoP facilitates opportunities for experts and mentees affiliated with these national organizations to convene regularly despite barriers attributed to physical distance. The GEM‐SLP VCoP is built around multiple forms of mentorship, monthly mentee‐driven didactics, academic projects, and continued engagement of program graduates in VCoP leadership. GEM‐SLP fosters relationships through (1) themed mentoring calls (career paths, work/life balance, etc); (2) functional mentorship through didactics and academic projects; and (3) near‐peer mentoring, provided by mentors near the mentees’ stage of education and experience. Monthly mentee‐driven didactics focus on introducing essential GEM principles while (1) critically analyzing literature based on a journal article; (2) building a core knowledge base from a foundational textbook; (3) applying knowledge and research to a project proposal; and (4) gaining exposure to training and career opportunities via mentor career presentations. Group academic projects provide a true GEM apprenticeship as mentees and mentors work collaboratively. GEM‐SLP mentees found the VCoP beneficial in building fundamental GEM skills and knowledge and forming relationships with mentors and like‐minded peers. GEM‐SLP provides a framework for developing mentorship programs and VCoPs in emergency medicine, especially when niche interests or geographic distance necessitate a virtual format.

Keywords: distance education, educational models, emergency medicine, global health, medical education, medical students, mentoring

1. INTRODUCTION

During the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic, social distancing measures necessitated innovative solutions to make didactics interactive, small group discussions engaging, and mentor relationships authentic, all in virtual formats. Global emergency medicine (GEM) education programs unite teachers and learners or mentors and mentees, often separated by continents. Generally, those with niche emergency medicine interests often collaborate between institutions and from diverse locations. Despite social or physical distance, building peer and mentor relationships around shared learning experiences and academic inquiry remains essential. Communities of practice (CoPs) engage members around knowledge and experiences related to a central interest. A virtual CoP (VCoP) uses technology to allow broader membership. We describe our experience building an international VCoP for fostering GEM mentorship for medical students.

2. VIRTUAL COMMUNITIES OF PRACTICE

CoPs form as individuals with a common interest exchange knowledge and experience, allowing for mutual learning amongst members and ultimately for members to apply new knowledge to their own practice. 1 , 2 Notable benefits of a CoP are providing a safe environment for learning and mentorship; improving knowledge, skill, and experience; fostering professional identity; identifying useful skills within a group; and increasing implementation of evidence‐based practice. 2 All CoPs share the following 3 basic facets: (1) domain, (2) community, and (3) practice. Domain refers to shared interests that tie the CoP group together. Community refers to relationships between CoP members built on shared interests and experiences. Practice refers to the CoP's joint activities, discussions, and resources. 3 , 4

A CoP is built on apprenticeship. Newcomers to the CoP become increasingly core members through active participation and mentorship. They gain skills and assume more responsibility, taking on the roles and norms of the community. 1 , 3 , 5 A CoP is bidirectional as members are transformed through participation and their participation in turn transforms the community. 5

A VCoP uses technology to access a larger community with which to share knowledge and build relationships. 3 Virtual platforms facilitate either real‐time or asynchronous communication between members. A VCoP expands resources for collaboration and reduces professional isolation by overcoming barriers including those related to geography, cost, time, and hierarchy. 3 , 5 These groups can take a number of forms. Open VCoP networks allow for brief interactions between a large number of loosely connected members, for example, Twitter‐based communities such as #FOAMed. Blog‐based open VCoP groups foster discussions around curated topics most often through discussion boards, such as EMDocs. Closed VCoP networks have selective membership, allowing for a safe space for junior learners and better facilitation of both peer and mentor networking targeted to a specific career stage. 3

One example of a closed VCoP in emergency medicine is the Acedemic Life in Emergency Medicine (AliEM) Mid‐Career Incubator Program. This is a year‐long VCoP‐based mentorship program that is largely virtual with intermittent in‐person meetings scheduled concurrently with national conferences. It uses project‐based mentorship, group assignments, monthly independent didactic modules on core‐curriculum topics, and asynchronous discussion via Slack. 6 Another example is CanadiEM, a volunteer‐driven non‐profit producing free open‐access medical education that uses a VCoP to provide apprenticeship training to newer writers and editors. 7

3. GEM STUDENT LEADERSHIP PROGRAM

Globally, there is a profound need for emergency medicine. In low‐ and middle‐income countries, it is estimated that 24 million lives are lost each year as a result of injuries and illnesses that could be effectively treated with prehospital and emergency care. 8 GEM seeks to assist in building acute care health systems and emergency care capacity in low‐resource settings. The scope of GEM is broad and includes emergency medicine development, delivery of acute care in resource‐limited settings, and disaster and humanitarian response. 9

Interest in GEM is growing rapidly among medical students and trainees. Although GEM fellowship opportunities are increasing, there are limited opportunities for GEM mentorship, education, and career guidance for medical students. This gap is partly attributed to limited numbers of trained GEM faculty members and uneven distributions of these faculty members between institutions. 10 , 11

Several national societies have addressed the need for increased equitable access to education and mentorship in GEM. The Emergency Medicine Residents’ Association (EMRA) created The Nuts and Bolts of Global Emergency Medicine. 9 The Society for Academic Emergency Medicine created the “Resident and Medical Student Roadmap for Global Emergency Medicine” and discussed challenges in training GEM leaders and academicians at the 2019 Global Emergency Medicine Academy Annual Meeting. 11 However, the authors are unaware of any other national US‐based GEM mentorship programs that provide active mentorship for medical students.

To address this mentorship gap, the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) International Section and the EMRA International Committee established the GEM Student Leadership Program (SLP) in 2018. This joint effort combined the resources of EMRA, the oldest and largest resident organization in the world with >16,000 student, resident, and alumni members, and the ACEP International Section, which has 2100 members.

The ACEP Ambassador Program provided a foundation for the program, linking mentees with ACEP members working in >80 countries. The ambassadors, who are academic and community emergency physicians working in worldwide emergency medicine development, served as faculty mentors in GEM‐SLP. Mentees were EMRA medical student members recruited on national and international levels through EMRA and ACEP International Section publicity and social media. Both mentees and mentors applied for positions in the GEM‐SLP VCoP each spring. Applications were reviewed, and new members were accepted by the leadership team.

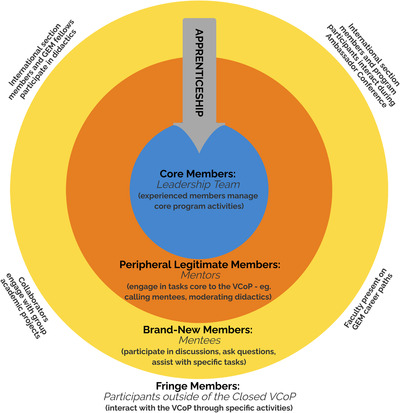

The GEM‐SLP program was created as a closed VCoP around the domain, or shared interest, of GEM. The program sought to introduce foundational knowledge and skills needed to work in GEM, stressing the importance of ethical, equitable, and sustainable approaches. The GEM‐SLP VCoP was structured using the framework of a CoP based on the original theory by Lave and Wegner, as illustrated in Figure 1. 12 Accepted mentees were the VCoP's brand new members, and apprenticeship began through mentored participation in GEM‐SLP activities and discussions. Mentors joined the VCoP as peripheral legitimate members, assisting in VCoP tasks. Fringe members—although not admitted to the closed VCoP—could interact through yearly ambassador conferences, participation in GEM‐SLP didactics, collaboration on academic projects, and faculty career presentations. All GEM‐SLP program graduates and mentors were invited to stay involved in the VCoP moving into central roles as part of the leadership team in continued apprenticeship under established leaders. This increased sustainability of the VCoP and infused new energy and perspectives. The community's practice—or shared activities, discussions, and resources—consisted of mentoring calls, didactics, and mentored academic projects as illustrated in Table 1 and Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

The Global Emergency Medicine (GEM) Student Leadership Program virtual community of practice (VCoP) structure. This framework illustrates how different groups actively engaged with the VCoP, both learning from and transforming the community. Apprenticeship allowed participants at all levels the opportunity to transition to VCoP leadership roles through active engagement in VCoP activities

TABLE 1.

Activities of the GEM‐SLP VCoP

| Element | Subcomponent | Description | Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multifaceted mentorship | Speed‐mentoring calls | Quarterly themed calls (eg, career paths in GEM) | Allowed for multiple perspectives and sources of goal‐directed advice |

| Mentees selected mentors to meet with based on shared GEM interests and VCoP interactions | Assisted mentees in identifying possible long‐term mentors | ||

| Summaries of mentee interests and prior meetings were provided for mentors to review before the calls to increase continuity | |||

| Functional mentorship–didactic preparations | Mentorship focused on obtaining the skills needed to prepare and present a didactic session | Mentorship on practical skills and professionalism | |

| Monthly mentee‐driven didactics | Journal articles | Journal articles relating to the monthly topic were selected and presented by the mentees | Building a working knowledge of the body of literature |

| Critically analyzing literature | |||

| Discussion of practical application of research findings | |||

| Book chapters | Preselected chapters from foundational global health texts aligned with the monthly topic were presented by the mentees | Building core knowledge in the topic area | |

| Project proposals | Project proposals described a theoretical GEM intervention related to the monthly topic (eg, implementing a first aid training course for motorcycle taxi drivers in Rwanda) | Implementing didactic knowledge and research in a practical application | |

| Career presentations | Attending physicians actively involved in GEM discussed their career paths and current work | Learning about training and career opportunities | |

| Mentored group academic projects | — | Functional mentorship provided through work on sustainable GEM academic projects in groups of 2 to 5 mentees with 1 mentor | Building practical skills |

| Networking with mentor and peers with shared interest |

Abbreviations: GEM‐SLP, Global Emergency Medicine Student Leadership Program; VCoP, virtual community of practice.

4. ACTIVITIES OF GEM‐SLP VCOP

4.1. Multifaceted mentorship

Mentorship was at the core of the GEM‐SLP VCoP for mentees and junior members of the leadership team. Mentor–mentee relationships were fostered through multiple avenues, the most prominent of which were themed speed‐mentoring calls. Mentees selected the mentor for each call based on knowledge of the mentor's focus of GEM work and/or prior program interactions. Mentees could opt to meet with the same mentor for multiple calls or a different mentor for each call based on their personal preferences and mentor–mentee fit. Quarterly calls, initiated by the mentors, were approximately 30 minutes. To ensure that each call was progressive throughout the year, unique topics with discussion prompts were suggested for each call (eg, career paths, work/life balance), and brief meeting summaries were documented for mentor review before subsequent calls. Further mentorship needs or specific mentee interests were brought to the VCoP to identify relevant resources, such as other mentees with similar interests or mentors with related projects.

These speed‐mentoring calls leveraged the following 2 main strengths: (1) allowing multiple, short‐term relationships that provided varied perspectives and goal‐directed advice and (2) assisting mentees in identifying mentors with whom they might develop a long‐term relationship. 13 As GEM mentors are not available at all institutions and mismatches in mentor–mentee relationships have been shown to lead to a failure of support, this method maximized the opportunity to meet multiple mentors. 14 , 15 The VCoP created a centralized space for networking with diverse mentors based in the United States and internationally to increase the likelihood of a productive mentor–mentee match.

Functional mentorship was provided through didactic preparations and work on academic projects. Mentees learned how to critically appraise literature and prepare for dynamic discussions around fundamental global health and emergency medicine principles. Mentees also acquired skills in project planning, communication, writing, and evaluation.

Finally, the medical students and residents who form the core membership of the GEM‐SLP VCoP proved an excellent source of near‐peer mentoring, or mentoring by individuals close to the mentees’ stage of education and experience. 17 Longitudinal calls with GEM‐SLP resident co‐directors afforded opportunities for program participants to ask questions and give feedback. In addition, mentees learned about near‐peer's experience in GEM, medical school, residency, and the transition to postgraduate training. Furthermore, near peers within the VCoP shared knowledge and modeled leadership skills during program activities. 17

4.2. Monthly mentee‐driven didactics

The program held monthly didactic sessions, offering an opportunity for peers, mentors, and leaders to interact. These monthly discussions were structured around rotating fundamental GEM themes (eg, ethics of humanitarian work, sustainability in global health). These sessions also provided opportunities for ACEP International Section fringe members to engage in the VCoP. Many didactic participants later became mentees, mentors, and GEM‐SLP leaders.

Each didactic was prepared by 3 student mentees and an assigned mentor from the VCoP (resident or attending physician). The didactic team met before the didactics to practice presentations and prepare discussion questions, providing apprenticeship in planning and leading a VCoP discussion.

In GEM‐SLP VCoP didactics, each element contributed to building a practical GEM skill set for mentees. Book chapters corresponded to the monthly didactic themes and taught foundational knowledge. Journal articles were selected by mentee presenters to relate to the didactic theme. Discussion focused on knowledge and application of GEM literature. Proposals for possible GEM interventions related to the theme focused on practical application of knowledge. Lastly, presentations by mentors assisted mentees in understanding training and career opportunities in GEM. Each component is further described in Table 1.

4.3. Mentored group academic projects

Mentees worked with mentors on GEM academic projects to build practical skills and a GEM network in the mentees area of interest. Mentees ranked potential projects based on personal interests and country/region of focus. Teams of 2 or 3 mentees were matched with a faculty mentor. Examples of projects included literature reviews on the state of emergency care in various countries, curriculum development for emergency care training in Uganda, and a publication based on the ACEP Ambassador Country Reports. The variety of opportunities gave mentees insight into diverse avenues for GEM involvement.

5. RESULTS OF THE PROGRAM

A total of 38 medical student mentees from different countries (33 United States, 2 Caribbean, 1 India, 1 China, 1 Israel) have participated in GEM‐SLP and were selected from 120 applicants. A total of 20 ACEP International Ambassadors have served as mentors, with 2 residing in Mexico and Malawi. Of the program graduates, 21 have remained involved in the GEM‐SLP leadership team.

The GEM‐SLP VCoP hosted 23 didactics over 3 years. The most recent 2020/2021 academic year included 7 didactics with a total of 189 non‐unique participant attendances, including 143 by mentees, mentors, or program leaders from within the closed GEM‐SLP VCoP and 46 by fringe members from the ACEP International Section. International Section members, especially those training and working outside the United States, made significant contributions to robust discussions. Project presentations and career path presentations were added to the 2020/2021 didactic program content.

The GEM‐SLP VCoP community was notably important to mentees. Mentees ranked the program highly in terms of networking with peers interested in GEM. Mentees also noted the value of having dedicated core members of the VCoP, as expressed through qualitative feedback in Table 2. Mentees appreciated the variety of academic projects available due to the diverse GEM work of VCoP mentors. However, many recognized the limitations of completing projects within an academic year and planned to continue to work on their projects after program completion (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Qualitative mentee feedback on the GEM‐SLP VCoP

| Leadership | “The leadership of the program was excellent—the mentorship coordinators and journal club leaders never demanded more enthusiasm from participants than they brought themselves, so their attitude toward the group sessions really helped make the program feel meaningful.” |

| Mentorship components |

“I found [GEM‐SLP] very thorough and it was one of the best mentorship experiences I've had in terms of how many of the mentors I had a chance to speak with and connect with.” “[My mentor was] instrumental in helping me navigate a future in global EM. Through our discussions about partnership, I have a better appreciation for reciprocal learning opportunities and the importance of local project ownership.” |

| Didactic components |

“I liked having dedicated global health time each month during didactics and meeting all of the mentors & mentees.” “I think that discussions are the real opportunity for learning during the monthly mentee‐driven didactics, and I never thought the projects were as interesting or thought‐provoking as some of the articles and book chapters. I think if more time were reserved for discussion, didactics would be even more interesting.” “The reading topics covered essential global health concepts, but the most fruitful aspect was the conversations about real‐world examples with GEM colleagues around the world.” |

| Multiple‐mentor model | “I know there needs to be a good match between mentor and student, which can be hard to determine, but it often felt like I was repeating my interests without having much forward momentum call to call. That said, I did appreciate getting so many different perspectives from mentors, so I'm not sure how to balance these.” |

| Peer collaboration | “I think it would be great to develop a better relationship with the cohort. It is certainly easier said than done, but I think having a strong cohort that interacts with each other would be incredibly valuable as we are all in the same 1‐2 year window of our training and would feel more comfortable reaching out to each other and collaborating.” |

Abbreviations: GEM, Global Emergency Medicine; SLP, Student Leadership Program; VCoP, virtual community of practice.

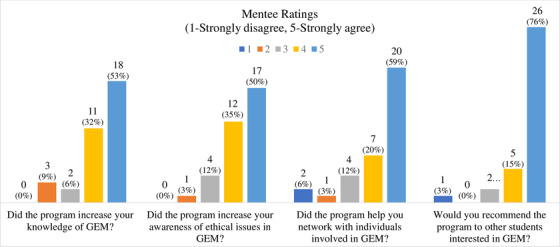

Anonymous mentee end‐of‐program evaluations assessing program effectiveness from all GEM‐SLP years to date (2018/2019–2020/2021) are presented in Figure 2. Mentees agreed that the program increased their knowledge of GEM, with 53% rating this as strongly agree and 32% as agree; 91% agreed or strongly agreed that they would recommend the program to other medical students interested in GEM (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Mentee evaluations of the Global Emergency Medicine Student Leadership Program (GEM‐SLP) from the 2018/2019–2020/2021 cohorts (n = 34)

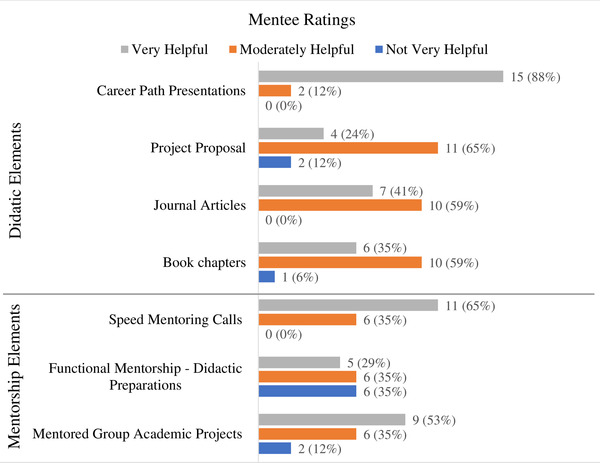

Mentee evaluations of the utility of the didactic and mentor components of the GEM‐SLP VCoP from the 2020/2021 year are shown in Figure 3. Career presentations were the most highly rated of the didactic elements; 88% reported them to be very helpful. All mentees felt the journal articles discussed were either moderately or very helpful. Every mentee also felt that speed‐mentoring calls were either moderately or very helpful, with 65% ranking this element as very helpful. Qualitative mentee feedback on both components is included in Table 2 (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Mentee evaluations of the Global Emergency Medicine Student Leadership Program (GEM‐SLP) didactics and mentorship from the 2020/2021 cohort (n = 17)

6. LESSONS LEARNED

Initially, the GEM‐SLP VCoP paired mentors and mentees 1‐to‐1. The pairs met at the ACEP International Section Ambassador Conference, an annual 1‐day preconference event at the ACEP Scientific Assembly, for an in‐person orientation to the program. Mentor–mentee relationships were strengthened through phone and virtual meetings throughout the year. However, varying levels of engagement were noted by some mentees and mentors, leading to diverse experiences. This feedback prompted the evolution from dyad mentor–mentee pairing to the multiple‐mentor model used currently.

The multiple‐mentor model fully leverages the benefits of a VCoP including access to expanded GEM networks, multiple mentor perspectives, increased mentor recruitment, and increased peer collaboration through group projects. However, the need to balance the opportunity to meet multiple mentors and build long‐term mentor relationships was highlighted by mentee feedback (Table 2). To address this, we transitioned to flexible mentoring opportunities, allowing for mentee personal preference and mentor–mentee fit. Mentees used published biographic information to identify mentors with similar GEM focus and regional interests, and multiple VCoP members contributed to new member mentorship.

Certain GEM‐SLP VCoP mentors have been strongly academic, whereas others have been more involved in program administration or clinical care globally. This diversity offered much to the VCoP. However, a limitation of the dyad matching was that, at times, mentees were paired with a mentor whose area of focus was poorly aligned with the mentees’ goals. Some clinically focused mentors also found providing an academic project burdensome. This was rectified in the multiple‐mentor VCoP model by allowing mentors to self‐select into leading a group academic project rather than requiring them to provide a project for a mentee.

There was a strong, initially underrecognized, desire for peer collaboration among the GEM‐SLP mentees, as expressed in a mentee feedback in Table 2. Mentees were seeking a community of like‐minded individuals rather than solely 1 mentor. Mentees made apt suggestions on how to facilitate peer interactions including small group breakouts during didactics, creating a WhatsApp or Facebook group, and allowing time for more non‐structured conversation during VCoP events. We have incorporated some of these suggestions into the VCoP for the coming year to increase community building.

The GEM‐SLP VCoP has had a mutually beneficial relationship with the ACEP International Section. The mentees benefit from the diverse group of VCoP members, including trainees and faculty at all career stages and mentors working in academic and community settings in the United States and abroad. Faculty benefit from the opportunity to help train the next generation of GEM practitioners, assistance with their GEM projects, and networking with other GEM educators and academics. Overall, the ACEP International Section benefits from an infusion of energy and new perspectives and developing young leaders for future ACEP International Section goals.

7. LIMITATIONS OF THE PROGRAM

Specific to GEM, 1 limitation of the GEM‐SLP approach is that on‐the‐ground international GEM experiences can be difficult for medical students to obtain and are not a focus of the program. Also, not all aspects of GEM practice are represented, such as VCoP members working in all geographic regions or interest areas (emergency medical services, ultrasound, disaster medicine, medical education, capacity development, etc). Finally, the virtual nature of the program may limit organic relationship building; a video conference call may never replace an in‐person interaction.

The COVID‐19 pandemic's effect on the 2020/2021 program year is a limitation of our assessment of impact. Many 2020/2021 mentees mentioned “Zoom fatigue” in their impressions of the didactics. This may be a phenomenon associated specifically with the COVID‐19 pandemic; however, it does seem to have impacted evaluations. The pandemic also posed challenges for the academic projects because of travel being extremely limited and many international partners focused on COVID‐19 response. This may have impacted mentee impressions of this VCoP activity for the 2020/2021 academic year.

8. FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Our primary goal for the GEM‐SLP VCoP is to continue to increase and diversify our membership. To date, we have recruited mentors solely from the ACEP International Ambassador Program. We expanded our mentor recruitment to all attending and fellow ACEP International Section members to increase our mentor pool and allow mentees to learn from GEM experts working in more diverse regions and focus areas and additional mentors working primarily outside of the United States. Integrating GEM fellows will provide additional perspectives on pathways to formal GEM training programs for mentees. Fellows will gain mentorship and leadership experience. Furthermore, we will continue to expand our mentee group focusing on prioritizing medical students training outside the United States to better support the bilateral exchange that is important in GEM learning. 18 In addition, we have started a blog and plan to build strategic partnerships with international emergency medicine organizations to broaden the VCoP's reach.

As the GEM‐SLP program is both unique in its aims and fairly new, the leadership team is continuously engaged in quality improvement. We obtain feedback from both the GEM‐SLP mentees and mentors through informal conversations and formal year‐end written feedback. To further improve the program, assessment of its impact on mentee knowledge and skills across GEM domains is needed. To date, there are few defined competencies and assessment tools to gauge the effectiveness of GEM learning experiences. 19 , 20

To address this need, the Global Emergency Medicine Think Tank Education Working Group developed the Global Health Milestones Tool for learners in emergency medicine. This is a yet unvalidated assessment tool that rates trainee competency across 11 domains essential to work in GEM, including global burden of disease, social and environmental determinants of health, capacity strengthening, and program management. 10 Starting in the 2020/2021 program year, we began to use the tool for programmatic quality improvement as a pre/post mentee self‐assessment. Although this specific tool is not applicable outside of GEM, there is a strong likelihood that similar tools may be available and of use in building VCoP for trainees within other emergency medicine interest areas.

9. GENERALIZING THE PROGRAM

The relevance and applicability of this model to GEM specifically and for medical education more broadly is clear. It provides a framework to foster mentorship, peer networking, and community, despite distance. The GEM‐SLP VCoP model could be emulated by other programs seeking to increase mentorship in GEM and bilateral exchange, including national and international emergency medicine organizations, medical student groups, medical schools, and residencies. Mentorship by international mentors is important for early career global health practitioners, and a VCoP model addresses barriers in obtaining mentorship from emergency medicine leaders abroad.

This approach is equally applicable to emergency medicine education in general, especially for niche interest groups whose members are at increased risk for academic isolation. It addresses the limitations of in‐person mentoring models, later reinforced by social distancing required because of the COVID‐19 pandemic. A completely virtual CoP model has allowed greater opportunity for breaking down academic silos and barriers related to traveling for in‐person meetings including expenses and scheduling conflicts. The VCoP model also allows increased equity in access for US‐based and international mentees and mentors alike.

A well‐cultivated VCoP typically includes educational content and discussion, mentoring, member engagement and ownership, credibility achieved through expert oversight, and lastly, the energy needed to nurture the community over time. 21 The GEM‐SLP VCoP model addresses each of these key areas. Furthermore, a successful VCoP allows for varying levels of engagement based on the interest, availability, and experience of each member. However, they also ensure all—from newcomers to core members—are included and gain benefits from participation leading to intrinsic motivation to contribute to the CoP. 3 We believe that the GEM‐SLP VCoP achieves these goals, benefiting all mentors, mentees, and the ACEP International Section, leading to continued community engagement. Similar engagement could be replicated in broader applications of the model.

10. CONCLUSION

The GEM‐SLP VCoP is a model for GEM mentorship of medical students within the structure of a national specialty society. GEM‐SLP mentees found the program beneficial in building fundamental GEM skills and knowledge as well as relationships with mentors and a like‐minded peer cohort. The GEM‐SLP framework can be used in developing mentorship programs and VCoPs in emergency medicine, especially when niche interests or geographic distance necessitate a virtual format.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the mentors, mentees, and leadership team without whom the Global Emergency Medicine Student Leadership Program Community of Practice would not be possible.

Pickering A, Patiño A, Garbern SC, et al. Building a virtual community of practice for medical students: The Global Emergency Medicine Student Leadership Program. JACEP Open. 2021;2:e12591. 10.1002/emp2.12591

An abstract based on a portion of this work was accepted for presentation at the American College of Emergency Physicians 2021 Research Forum and will be published in the Annals of Emergency Medicine supplement (962) titled “Building a Virtual Community of Global Emergency Medicine Mentorship and Learning–ACEP & EMRAs’ Global Emergency Medicine Student Leadership Program (GEMS‐LP).”

Funding and support: By JACEP Open policy, all authors are required to disclose any and all commercial, financial, and other relationships in any way related to the subject of this article as per ICMJE conflict of interest guidelines (see www.icmje.org). The authors have stated that no such relationships exist.

Supervising Editor: Henry Wang, MD, MS.

REFERENCES

- 1. Wenger E. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 2. McLoughlin C, Patel KD, O'Callaghan T, Reeves S. The use of virtual communities of practice to improve interprofessional collaboration and education: findings from an integrated review. J Interprof Care. 2018;32(2):136‐142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yarris LM, Chan TM, Gottlieb M, Juve AM. Finding your people in the digital age: virtual communities of practice to promote education scholarship. J Grad Med Educ. 2019;11(1):1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wenger E, McDermott R & Snyder WM. Cultivating Communities of Practice. Brighton, Massachusetts: Harvard Business Review Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mann KV. Theoretical perspectives in medical education: past experience and future possibilities. Med Educ. 2011;45(1):60‐68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chan TM, Gottlieb M, Sherbino J, et al. The ALiEM faculty incubator: a novel online approach to faculty development in education scholarship. Acad Med. 2018;93(10):1497‐1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ting DK, Thoma B, Luckett‐Gatopoulos S, et al. Canadi EM: accessing a virtual community of practice to create a canadian national medical education institution. AEM Educ Train. 2019;3(1):86‐91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hsia RY, Thind A, Zakariah A, Hicks ER, Mock C. Prehospital and emergency care: updates from the disease control priorities, version 3. World J Surg. 2015;39(9):2161‐2167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Roberts J, Lin J & Weiner S. The Nuts and Bolts of Global Emergency Medicine. Des Plaines, Illinois: Society of Academic Emergency Medicine; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Douglass KA, Jacquet GA, Hayward AS, et al. Development of a global health milestones tool for learners in emergency medicine: a pilot project. AEM Educ Train. 2017;1(4):269‐279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Newberry JA, Patel S, Kayden S, O'Laughlin KN, Cioè‐Peña E, Strehlow MC. Fostering a diverse pool of global health academic leaders through mentorship and career path planning. AEM Educ Train. 2020;4:S98‐S105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lave J, Wenger E. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Thampy HK, Ramani S, McKimm J, Nadarajah VD. Virtual speed mentoring in challenging times. Clin Teach. 2020;17(4):430‐432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Britt RC, Hildreth AN, Acker SN, Mouawad NJ, Mammen J, Moalem J. Speed mentoring: an innovative method to meet the needs of the young surgeon. J Surg Educ. 2017;74(6):1007‐1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kurré J, Schweigert E, Kulms G, Guse AH. Speed mentoring: establishing successful mentoring relationships. Med Educ. 2014;48(11):1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Thorndyke LE, Gusic ME, Milner RJ. Functional mentoring: a practical approach with multilevel outcomes. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2008;28(3):157‐164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Akinla O. A systematic review of the literature describing the outcomes of near‐peer mentoring programs for first year medical students. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Karim N, Rybarczyk MM, Jacquet GA, et al. COVID‐19 pandemic prompts a paradigm shift in global emergency medicine: multidirectional education and remote collaboration. AEM Educ Train. 2020;5(1):79‐90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sawleshwarkar S, Negin J. A review of global health competencies for postgraduate public health education. Front Public Health. 2017;5:46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jahn HK, Kwan J, O'Reilly G, et al. Towards developing a consensus assessment framework for global emergency medicine fellowships. BMC Emerg Med. 2019;19(1):68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nagy P, Kahn CE, Boonn W, et al. Building virtual communities of practice. J Am Coll Radiol. 2006;3(9):716‐720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]