Abstract

Background

This review is one in a series of reviews of interventions for lateral elbow pain.

Objectives

To determine the effectiveness and safety of extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT) for lateral elbow pain.

Search methods

Searches of the Cochrane Controlled Trials Register (Cochrane Library Issue 2, 2004), MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, and Science Citation Index (SCISEARCH) were conducted in February 2005, unrestricted by date.

Selection criteria

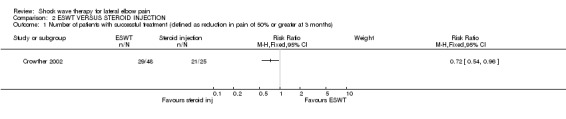

We included nine trials that randomised 1006 participants to ESWT or placebo and one trial that randomised 93 participants to ESWT or steroid injection.

Data collection and analysis

For each trial two independent reviewers assessed the methodological quality and extracted data. Methodological quality criteria included appropriate randomisation, allocation concealment, blinding, number lost to follow up and intention to treat analysis. Where appropriate, pooled analyses were performed. If there was significant heterogeneity between studies or the data reported did not allow statistical pooling, individual trial results were described in the text.

Main results

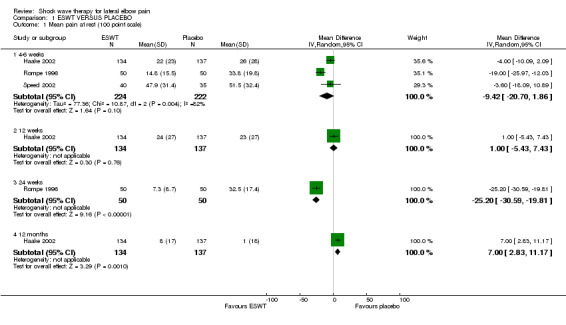

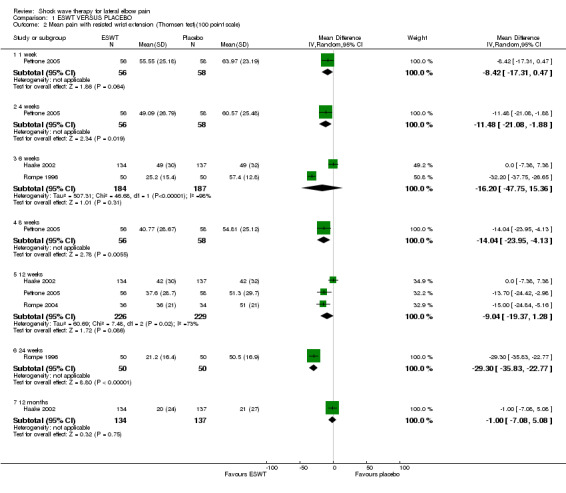

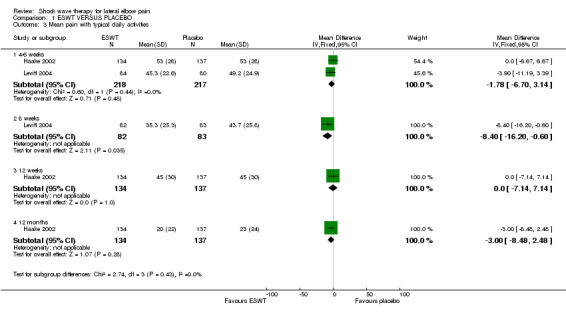

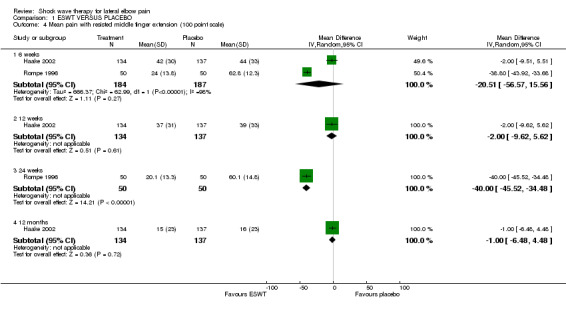

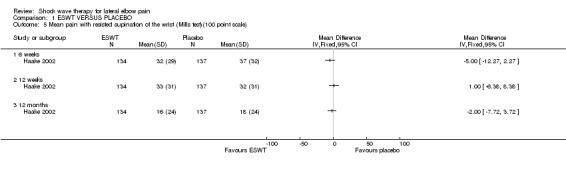

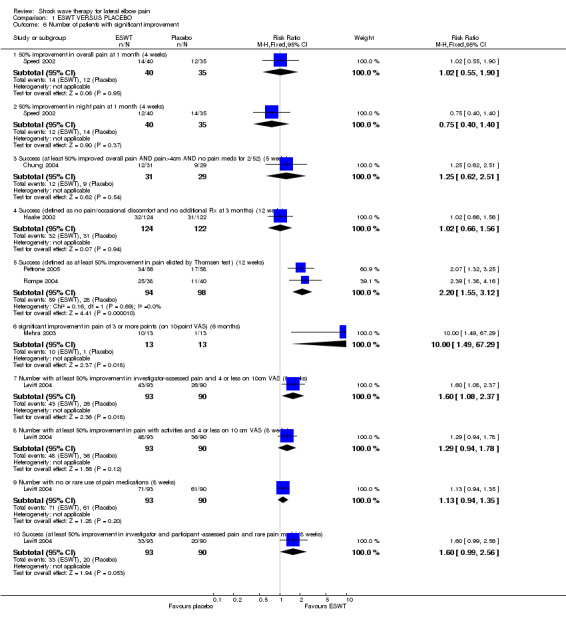

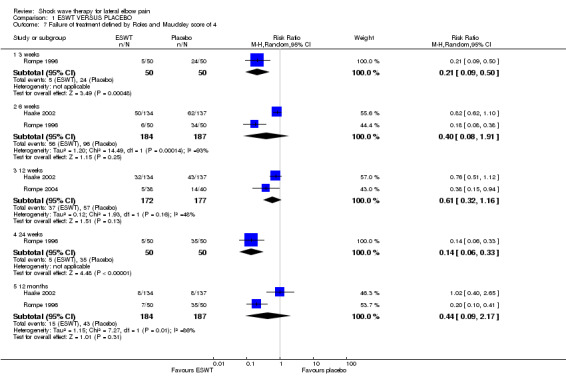

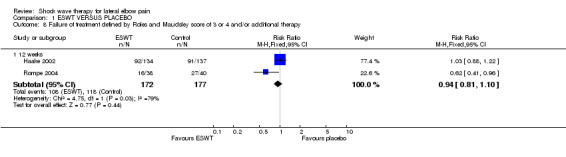

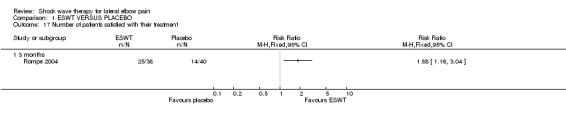

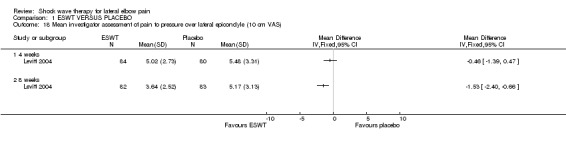

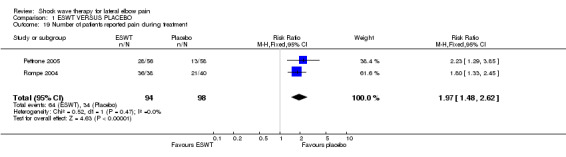

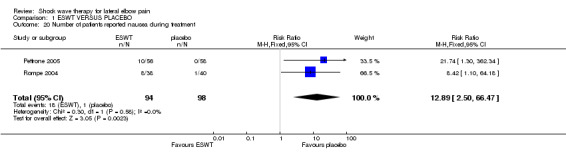

Eleven of the 13 pooled analyses found no significant benefit of ESWT over placebo. For example, the weighted mean difference for improvement in pain (on a 100‐point scale) from baseline to 4‐6 weeks from a pooled analysis of three trials (446 participants) was ‐9.42 (95% CI ‐20.70 to 1.86) and the weighted mean difference for improvement in pain (on a 100‐point scale) provoked by resisted wrist extension (Thomsen test) from baseline to 12 weeks from a pooled analysis of three trials (455 participants) was ‐9.04 (95% CI ‐19.37 to 1.28). Two pooled results favoured ESWT. For example, the pooled relative risk of treatment success (at least 50% improvement in pain with resisted wrist extension at 12 weeks) for ESWT in comparison to placebo from a pooled analysis of two trials (192 participants) was 2.2 (95% CI 1.55 to 3.12). However this finding was not supported by the results of four other individual trials that were unable to be pooled. Steroid injection was more effective than ESWT at 3 months after the end of treatment assessed by a reduction of pain of 50% from baseline (21/25 (84%) versus 29/48 (60%), p<0.05). Minimal adverse effects of ESWT were reported. Most commonly these were transient pain, reddening of the skin and nausea and in most cases did not require treatment discontinuation or dosage adjustment.

Authors' conclusions

Based upon systematic review of nine placebo‐controlled trials involving 1006 participants, there is "Platinum" level evidence that shock wave therapy provides little or no benefit in terms of pain and function in lateral elbow pain. There is "Silver" level evidence based upon one trial involving 93 participants that steroid injection may be more effective than ESWT.

Plain language summary

Shock wave therapy for elbow pain

Does shock wave therapy work to treat tennis elbow and is it safe? To answer this question, scientists analyzed 9 studies testing over 1000 people who had tennis elbow. Most people had pain for a long period of time and the pain had not improved with other treatments. People tested received either shock wave therapy or fake therapy 3 times over 3 weeks to 3 months. Improvement was tested after 1 week to 12 months. These studies provide the best evidence we have today. What is tennis elbow and how could shock wave therapy help? Tennis elbow or lateral epicondylitis can occur for no reason or be caused by too much stress on the tendon at the elbow. It can cause the outside of the elbow and the upper forearm to become painful and tender to touch. Pain can last for 6 months to 2 years, and may get better on its own. Many treatments have been used to treat tennis elbow, but it is not clear whether these treatments work or if the pain simply goes away on its own. Shock wave therapy involves sending sound waves to the elbow by a machine. It is not well known why and how it might work to improve pain.

What did the studies show? Five studies show that pain, function and grip strength was the same or slightly more improved with shock wave therapy than with fake therapy. Four studies show more improvement with shock wave therapy.

But when the results from some of the studies were pulled together, overall shock wave therapy improved symptoms just as well as fake therapy.

One study compared shock wave therapy to steroid injections. It shows that steroid injections may improve symptoms more than shock wave therapy. Were there side effects? Side effects usually did not last long and went away after therapy. Side effects included pain and reddening of the skin where the shock wave therapy was given, and some people had nausea. What is the bottom line? There is "Platinum" level evidence that shock wave therapy provides little or no benefit in terms of improving pain and function in tennis elbow. Shock wave therapy may cause pain, nausea and reddening of the skin.

This review does not support the use of shock wave therapy.

Background

This Cochrane review is one of a series of Cochrane reviews of interventions for lateral elbow pain.

'Lateral elbow pain' is described by many analogous terms in the literature, including "tennis elbow", "lateral epicondylitis", "lateral epicondylalgia", "rowing elbow", "tendonitis of the common extensor origin", and "peritendonitis of the elbow". For the purposes of this review the term "lateral elbow pain" will be used as it best describes the site of the pain, and will allow for greater clarity of inclusion. Lateral elbow pain is common; the prevalence in the population is 1‐3% (Allander 1974) and causes considerable morbidity and financial cost. Peak incidence is 40‐50 years. Although lateral elbow pain is generally self limiting, in a minority of people symptoms persist for 18 months to 2 years and in some cases for much longer (Hudak 1996a). A small proportion eventually undergo surgery although reliable data on surgical rates in unselected patients are lacking. The cost is therefore high, both in terms of lost productivity and healthcare use. In a general practice trial of an expectant waiting policy, 80% of the people with elbow pain of already greater than 6 weeks duration had recovered after 1 year (Smidt 2002).

It is believed that the majority of cases of lateral elbow pain are due to a musculotendinous lesion of the common extension origin at the attachment to the lateral epicondyle (Chard 1989). Focal changes such as focal hypoechoic areas of degeneration, discrete cleavage tears (both partial and complete) and involvement of the lateral collateral ligament can be identified on sonographic examination of the common extensor origin in participants with lateral elbow pain (Connell 2001).

Shock waves are single pulsed acoustic or sonic waves, which dissipate mechanical energy at the interface of two substances with different acoustic impedance (Loew 1997). They are produced by generators of an electrical energy source and require an electroacoustic conversion mechanism and a focusing device (Ueberle 1997). Three types of systems can be distinguished based upon the sound source ‐ electrohydraulic, electromagnetic and piezoelectric systems. Since 1976, shock wave therapy in the form of lithotripsy has been used to disintegrate renal and biliary calculi (Chaussy 1982). From the early 1990's there have been published descriptions of its use in Germany in a variety of musculoskeletal disorders including delayed and nonunion of fractures (Valchanou 1991), calcific tendinitis of the shoulder (Loew 1997), lateral and medial epicondylitis (Haake 2002, Dahmen 1992, Rompe 1996‐2) and painful heel (Rompe 1996‐2).

In 1995, the German Society of Shock Wave Therapy stated in a consensus conference that extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT) can be used to treat four orthopaedic conditions including tendinosis calcarea (calcific tendinitis), calcaneal spur (painful heel or plantar fasciitis), epicondylitis humeri radialis (lateral elbow pain) and pseudoarthrosis (false joint) and reimbursement of ESWT by the compulsory health insurers was accepted (Wild 2000). By the end of 1996, 40,000 applications for reimbursement of ESWT for orthopaedic indications in Germany, representing DM 30 million (15 million Euro) had been received (Wild 2000). Currently, there is an estimated 60,000 to 100,000 participants being treated with ESWT for musculoskeletal conditions each year in Germany (Schmitt 2001). It was also introduced into routine care in 1995 in Switzerland and Austria. Subsequently it is gaining acceptance in other parts of the world for some musculoskeletal problems. For example, in 2000 the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the US approved a ESWT device for the treatment of chronic proximal plantar fasciitis based upon a trial performed in the USA (Henney 2000, Ogden 2001). The FDA have subsequently approved two ESWT devices for the treatment of lateral elbow pain in 2002 and 2003 respectively (Pettrone 2005; Levitt 2004)(for FDA references see References to included studies) and clinical studies are also being performed elsewhere including Taiwan (Ko 2001) and Australia (Buchbinder 2001).

How ESWT results in the symptomatic improvement of lateral elbow pain is not well understood. The electrophysiological pathways and molecular mechanisms of the proposed anti‐nocioceptive effect (blockage of activation of nocioceptors which are receptors in the skin, deep structures and viscera that cause pain upon activation) of ESWT are still unknown (Haake 2002). Rompe et al have hypothesised that there is an overstimulation of nerve fibres resulting in an immediate analgesic effect (hyperstimulation analgesia) (Rompe 1996, Melzack 1975). Physical effects on cell permeability and induction of diffusible radicals has also been postulated to cause disruption of the tendon tissue resulting in induction of a healing process (Loew 1997). In a rabbit model, increasing doses of ESWT were associated with changes in the Achilles tendon and paratendon (Rompe 1998). No changes were observed in the group of rabbits who received 1000 impulses of an energy flux density of 0.08 mJ/mm2 whereas transient swelling of the tendon and minor inflammatory reaction were observed in rabbits who received 1000 impulses of 0.28 mJ/mm2 and formation of paratendinous fluid, tendon swelling and marked histological changes including increased eosin staining, fibrinoid necrosis, fibrosis in the paratendon and infiltration of inflammatory cells in the group who received 1000 impulses of 0.60 mJ/mm2.

Techniques for using ESWT for musculoskeletal problems have not yet been standardised and the precise dosages and the optimal frequency of application have not been studied extensively. There is still no consensus on when to differentiate between low‐ and high‐energy shock wave applications, although Wild et al report that a differentiation between high‐energy shock waves with an energy flux density of 0.2‐0.4 mJ/mm2 (for use in calcific tendinitis and pseudoarthrosis) and low‐energy shock waves with a respective density of < 0.2 mJ/mm2 (for use in lateral elbow pain and heel pain) is well accepted (Wild 2000). Other outstanding issues include whether the shock waves should be directed to the target area solely by determining the site of maximal tenderness or whether radiological or ultrasound imaging, in addition to clinical methods, can increase the accuracy with which shock waves are delivered to abnormal areas (and thereby possibly increasing their efficacy); and whether local anaesthetic injections should be used in the target area prior to treatment to reduce painful reactions or whether this precludes accurate targeting of the pathology.

The effectiveness of ESWT in the treatment of lateral elbow pain has been systematically reviewed before (Boddeker 2000, Buchbinder 2001). Boddeker et al included 20 studies, of which only one was a randomised controlled trial (RCT) (Rompe 1996). The other 19 included studies were case series reporting beneficial effects of ESWT. In our original review our conclusions were inconclusive, due to conflicting results of the two included RCTs (Buchbinder 2001). Since that time, more RCTs have been performed and so we have updated our original review by including all currently available RCTs examining the effectiveness of ESWT for lateral elbow pain.

Objectives

To determine the effectiveness and safety of ESWT for lateral elbow pain.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in any language were included in this systematic review.

Types of participants

Studies of adults (>16 years) with lateral elbow pain were included. Lateral elbow pain was defined as elbow pain which is maximal over the lateral epicondyle, and increased by pressure on the lateral epicondyle and resisted dorsiflexion of the wrist and/or middle finger. RCTs that included participants with a history of significant trauma or systemic inflammatory conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis were excluded. Studies of various soft tissue diseases and pain due to tendinitis at all sites were included provided that the lateral elbow pain results were presented separately or > 90% of participants in the study had lateral elbow pain.

Types of interventions

All randomised controlled comparisons of ESWT versus placebo, or another modality, or of varying types and dosages of shock wave therapy were included, and comparisons established according to intervention.

Types of outcome measures

All outcomes measured in the trials were reported. These included overall pain, pain at rest and with activities and resisted movements, function/ disability (Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH) and the Upper Extremity Function Scale (UEFS), quality of life (EQ‐5D thermometer), Roles and Maudsley score, grip strength, satisfaction with abilities to perform full activities and sport, composite endpoints of 'success' of treatment as defined in the various trials, and adverse effects.

Search methods for identification of studies

Randomised trials were identified from searches of the Cochrane Controlled Trials Register (Cochrane Library Issue 2, 2004), MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, and Science Citation Index (SCISEARCH). Searches were conducted in February 2005 and were not restricted by date. The following search strategy (Appendix 1) was used to search MEDLINE, and was adapted for the remaining databases. As this is one in a series of reviews for lateral elbow pain, it was decided to not to include search terms for specific interventions, but simply to identify all possible trials related to lateral elbow pain. The reference lists of all identified studies and correspondence relating to those studies were also searched.

Data collection and analysis

STUDY SELECTION Two reviewers (RB or JY) independently reviewed the identified trials to determine those that met the inclusion criteria. Full articles describing trials were obtained and translated where necessary, and the same two reviewers independently applied the selection criteria to the studies. There was complete consensus concerning the final inclusion of RCTs.

METHODOLOGICAL QUALITY ASSESSMENT The methodological quality of each RCT was independently assessed by two reviewers (not always the same pair of reviewers). It was planned to use consensus to resolve disagreements with a third reviewer to be consulted if disagreements persisted, however there were no disagreements.

As in the previous review, the methodological quality of included trials was assessed based upon whether the trials met key criteria (appropriate randomisation, allocation concealment, blinding, number lost to follow up and intention to treat analysis). Failure to fulfil these criteria were considered to have potentially biased the overall outcome of the included trial. Allocation concealment was ranked as: A: adequate; B: unclear; or C: inadequate. All other information concerning trial quality was recorded on a pre‐piloted data extraction sheet and later transposed into the Table of Included Studies.

DATA EXTRACTION Two reviewers independently extracted the data on the study characteristics including source of funding, study population, intervention, analyses and outcomes using standardised data extraction forms. The authors of recent original studies were contacted to obtain more information when needed.

In order to assess efficacy, raw data for outcomes of interest (means and standard deviations for continuous outcomes and number of events for binary outcomes) was extracted where available in the published reports. Wherever reported data was converted or imputed, this was recorded in the notes section of the Table of Characteristics of included studies.

ANALYSIS The results of each RCT were plotted as point estimates, i.e., relative risks with corresponding 95% confidence interval for dichotomous outcomes, and mean and standard deviation for continuous outcomes. When the results could not be shown in this way, they were described in the table of included studies. For continuous measures, preference was given to analyse the results with weighted mean differences because these results are easier to interpret for clinicians/readers. If this was not possible (due to different trials using different scales and/or inability to convert data into the same scale), then standardized mean differences or effect sizes were used. The studies were first assessed for clinical homogeneity with respect to the duration of the disorder, type, frequency and total dose of ESWT, control group and the outcomes. Clinically heterogeneous studies were not combined in the analysis, but separately described. For studies judged as clinically homogeneous, statistical heterogeneity was tested by Q test (chi‐square) and I2. Clinically and statistically homogeneous studies were pooled using the fixed effects model. Clinically homogeneous and statistically heterogeneous studies were pooled using the random effects model.

For the purposes of comparison and pooling data, the timing of follow up has been described in this review by number of weeks, months etc following the completion of treatment irrespective of when and how many treatments were given. Where appropriate, results were grouped according to the timing of follow‐up from the completion of treatment as either: a. immediately after the end of treatment up to 1 week after the end of treatment b. short‐term follow‐up (4 to 6 weeks after the end of treatment) c. intermediate follow‐up (12 to 24 weeks after the end of treatment) d. long‐term follow‐up ( 1 year or longer, after the end of treatment)

GRADING THE STRENGTH OF THE EVIDENCE The common system of grading the strength of scientific evidence for a therapeutic agent that is described in the CMSG module scope and in the Evidence‐based Rheumatology BMJ book (Tugwell 2003) and was used to rank the evidence included in this systematic review. Four categories are used to rank the evidence from research studies from highest to lowest quality: Platinum, Gold, Silver, and Bronze.

Platinum: A published systematic review that has at least two individual controlled trials each satisfying the following : ·Sample sizes of at least 50 per group ‐ if these do not find a statistically significant difference, they are adequately powered for a 20% relative difference in the relevant outcome. ·Blinding of patients and assessors for outcomes. ·Handling of withdrawals >80% follow up (imputations based on methods such as Last Observation Carried Forward (LOCF) are acceptable). ·Concealment of treatment allocation.

Gold: At least one randomised clinical trial meeting all of the following criteria for the major outcome(s) as reported: ·Sample sizes of at least 50 per group ‐ if these do not find a statistically significant difference, they are adequately powered for a 20% relative difference in the relevant outcome. ·Blinding of patients and assessors for outcomes. ·Handling of withdrawals > 80% follow up (imputations based on methods such as LOCF are acceptable). ·Concealment of treatment allocation.

Silver: A systematic review or randomised trial that does not meet the above criteria. Silver ranking would also include evidence from at least one study of non‐randomised cohorts that did and did not receive the therapy, or evidence from at least one high quality case‐control study. A randomised trial with a 'head‐to‐head' comparison of agents would be considered silver level ranking unless a reference were provided to a comparison of one of the agents to placebo showing at least a 20% relative difference.

Bronze: The bronze ranking is given to evidence if at least one high quality case series without controls (including simple before/after studies in which patients act as their own control) or if the conclusion is derived from expert opinion based on clinical experience without reference to any of the foregoing (for example, argument from physiology, bench research or first principles). The ranking is included in the synopsis and abstract of this review.

Results

Description of studies

Our review published in 2002 included two placebo‐controlled trials involving 115 and 271 participants respectively (Rompe 1996; Haake 2002). This updated review includes an additional seven placebo‐controlled trials involving 75, 24, 86, 60, 78, 114 and 183 participants respectively (Speed 2002; Mehra 2003; Melikyan 2003; Chung 2004; Rompe 2004; Pettrone 2005; Levitt 2004) and one trial of ESWT versus steroid injection involving 93 participants (Crowther 2002). Two trials are unpublished but are available from the FDA website (Levitt 2004; Pettrone 2005), although one of these is now in press (Pettrone 2005). All trials were published in English and one trial was also published in German (Rompe 1996). The trials were performed in Germany (Rompe 1996; Rompe 2004), Germany and Austria (Haake 2002), the UK (Crowther 2002; Mehra 2003; Speed 2002; Melikyan 2003), Canada (Chung 2004) and the US (Pettrone 2005; Levitt 2004). One study reported side effects in a separate report (Haake 2002).

INTERVENTIONS

A variety of devices were used to generate shock waves in the different trials although most appeared to use similar sets of shock wave parameters (See Additional tables 01). Six trials generated shock waves electromagnetically (Rompe 1996; Speed 2002; Melikyan 2003; Chung 2004; Rompe 2004; Pettrone 2005), one trial used electrohydraulic shock waves (Levitt 2004), in two trials the type of shock waves were not specified (Crowther 2002; Mehra 2003) and one trial used 8 different shock wave devices at different sites but all were comparable with respect to shock wave parameters as determined by a consensus report by the technical working group of the German Association for Shock Wave Lithotripsy (devices listed in Additional tables 01)(Haake 2002). Three trials administered local anaesthetic (3 ml of 1% mepivacaine (Haake 2002); 3‐5 ml 1% lignocaine (Mehra 2003) or local anaesthetic or a bier block (Levitt 2004)). Nine of the ten trials administered 3 treatments but the interval between treatments varied from 7 ± 1 days (Haake 2002); weekly (Rompe 1996; Crowther 2002; Chung 2004; Rompe 2004; Pettrone 2005); fortnightly (Mehra 2003); and monthly (Speed 2002). The interval between treatments was not provided for one trial (Melikyan 2003). One trial administered a single treatment (Levitt 2004).

The placebo control group comprised either a physical block to the shock waves (i.e. polyethylene foil filled with air to reflect the shock waves (Haake 2002; Rompe 2004); an air buffer pad to prevent the transmission of shock waves (Chung 2004); a clasp on the elbow that intercepted the shock waves (Mehra 2003); a foam pad which acted as a reflective medium by virtue of its air bubbles (Melikyan 2003); a sound‐reflecting pad between the patient and the application head of the machine (Pettrone 2005); a Styrofoam block placed against the coupling membrane of the shock head to absorb the shock waves and a fluid‐filled IV bag placed between the Styrofoam block and the subject's elbow to mimic the feel of the coupling membrane (Levitt 2004); a subtherapeutic dose of ESWT (i.e. 10 impulses of 0.08 mJ/mm2 (Rompe 1996); or minimal energy pulses of 0.04 mJ/mm2 in order to create the same sound with the treatment head deflated, no coupling gel and avoidance of skin contact (Speed 2002)(See Characteristics of Included Studies Table).

One trial compared ESWT to 20 mg triamcinolone made up to 1.5 ml with 1% lignocaine injected into the point of maximal tenderness at the extensor origin of the lateral epicondyle of the humerus (Crowther 2002).

STUDY PARTICIPANTS Nearly all trials recruited similar study populations (See Table of Characteristics of Included Studies). Participants all had lateral elbow pain with most studies also requiring evidence of localised tenderness at or near the common extensor tendon insertion at the lateral epicondyle and reproduction of pain with resisted movements (e.g.. resisted wrist or middle finger extension). Seven trials specified that participants had to have had a varying number and/or duration of unsuccessful conservative treatment/s prior to trial inclusion (Haake 2002; Mehra 2003; Melikyan 2003; Rompe 1996; Rompe 2004; Pettrone 2005; Levitt 2004) whereas one trial specifically included only participants who had not previously received any treatment (Chung 2004). One recent trial only included recreational tennis players defined as playing recreational tennis for at least 1 hour per week before symptoms occurred, with chronic symptoms of at least a year, and highly resistant to other forms of treatment (Rompe 2004).

Trials required that study participants have a minimum of 3 months (Speed 2002), 4 months (Crowther 2002), 6 months (Haake 2002; Pettrone 2005; Levitt 2004) or 12 months (Rompe 1996; Rompe 2004) duration of symptoms prior to inclusion in the trial, one trial specified that symptoms had to have been present for more than 3 weeks and less than a year (Chung 2004), while two trials did not specify a minimum duration of symptoms (Mehra 2003; Melikyan 2003). The mean duration of pain was generally long in 7 trials, with some trials including participants with symptoms for over 10 years (11 months in total study population (Mehra 2003); 24.8 months (range 10 to 120 months) and 21.9 months (range 10 to 46 months) in the ESWT and placebo groups respectively (Rompe 1996); 27.6 months (SD 35.5) and 22.8 months (SD 21.4) in the ESWT and placebo groups respectively (Haake 2002); 15.9 months (range 3‐42 months) and 12 months (range 3‐40 months) in the ESWT and placebo groups respectively (Speed 2002); 23.3 months (range 12‐120 months) and 25.1 months (range 12‐132 months) in the active and placebo groups respectively (Rompe 2004); 22.5 months (range 5.3‐161.7 months) and 4.1 months (range 4.1‐265.9 months) in the ESWT and placebo groups respectively (Levitt 2004); and 21.3 (range 6‐178 months) and 20.8 (range 6‐176 months) in the ESWT and placebo groups respectively (Pettrone 2005). The mean duration of symptoms was much shorter in one trial (19.8 weeks (SD 13.2) and 22.1 weeks (SD 15.7) in the ESWT and placebo groups respectively)(Chung 2004). The duration of symptoms of study participants was not reported in two trials (Crowther 2002; Melikyan 2003).

Mean age in 9 of the 10 trials was similar: 43.9 years (range 26‐61 years) and 41.9 years (range 26 to 58 years) in the ESWT group and placebo group respectively (Rompe 1996); 46.9 years (SD 8.5) and 46.3 years (SD 9.6) in the ESWT and placebo groups respectively (Haake 2002); 46.5 years (range 26‐70 years) and 48.2 years (range 31‐65 years) in the ESWT and placebo group respectively (Speed 2002); 43.4 years (range 35‐71 years) in the total study population (Melikyan 2003); 49 years (range 27‐69 years) in the total study population (Crowther 2002); 46.8 years (SD 6.6) and 45.5 years (SD 6.6) in the ESWT and placebo group respectively (Chung 2004); 45.9 years (SD 12.3) and 46.2 years (SD 11.2) in the ESWT and placebo groups respectively (Rompe 2004); and 47 years (range 35‐71 years) and 47.3 years (range 35‐60 years) in the ESWT and placebo groups respectively (Pettrone 2005); 44 years (range 22‐66 years) and 46 years (range 32‐71 years) in the ESWT and placebo groups respectively (Levitt 2004). One trial did not provide data on age (Mehra 2003). There were slightly more women in 6 trials (percentage of women: 58% (Rompe 1996); 53% (Haake 2002); 59% (Melikyan 2003); 56% Speed 2002); 52.6% (Pettrone 2005); 52.5% (Levitt 2004); 50% (Crowther 2002); 48.7% (Rompe 2004); 34% (Mehra 2003); 30.3% (Chung 2004)).

TIMING OF FOLLOW UP Follow up assessments were performed at varying time points across the trials, from during treatment to 12 months after the final treatment. Haake et al performed follow up assessments at 6 and 12 weeks and 12 months after the final treatment (Haake 2002). Mehra et al performed assessments at 3 and 6 months after the final treatment but only reported their 6‐month data (Mehra 2003). Melikyan et al performed assessments at 1, 3 and 12 months after the final treatment (Melikyan 2003). Rompe et al performed assessments immediately after completion of treatment and at 3, 6 and 24 weeks after completion of treatment (Rompe 1996). Speed et al performed assessments prior to the second and third treatments (at 1 and 2 months respectively) and at 1 month after the final treatment (at 3 months from baseline) (Speed 2002). Crowther et al performed assessments at 6 weeks and 3 months after either steroid injection or the end of completion of 3 weekly treatments of ESWT (Crowther 2002). Chung performed assessments at 1 and 5 weeks after the completion of treatment (Chung 2004). Rompe et al performed assessments at 3 and 12 months after completion of treatment although participants and assessors were unblinded at 3 months (Rompe 2004). Pettrone and McCall performed assessments at 1, 4, 8 and 12 weeks and 6 months and 12 months after the completion of treatment although participants and assessors could be unblinded at 12 weeks if participants had not achieved at least a 50% reduction in pain compared with baseline (Pettrone 2005). Levitt et al performed assessments at 4 and 8 weeks after the treatment (Levitt 2004).

OUTCOME ASSESSMENT Six trials specified a primary endpoint (Haake 2002, Speed 2002, Chung 2004, Rompe 2004, Pettrone 2005; Levitt 2004). Haake et al specified the primary endpoint as success rate after 12 weeks defined as subjective pain score of 1 or 2 on the Roles and Maudsley scale (1 = excellent (no pain, full movement and activity) and 2 = good (occasional discomfort, full movement, full activity)(See notes in Table of Characteristics of included studies) and no additional conservative or surgical treatment. Another trial also used the Roles and Maudsley scale and determined failure of treatment at 12 weeks, defined as a score of 4 = poor (pain limiting activities)(Rompe 1996). Speed et al specified the primary endpoint to be a 50% improvement in pain from baseline at 1 month after the end of treatment (Speed 2002). Chung and Wiley specified the primary endpoint as treatment success at 8 weeks (5 weeks after the completion of treatment) defined as fulfillment of all of the following 3 criteria (1) at least a 50% reduction in overall elbow pain as measured by overall pain VAS, (2) maximum allowable overall elbow pain score of 4.0 cm, and (3) no use of pain medications for lateral elbow pain for 2 weeks before the 8 week evaluation (Chung 2004). Both Pettrone and McCall and Rompe et al specified the primary endpoint as reduction in pain elicited by provocative Thomsen testing recorded on VAS at 12 weeks (or 3 months) following completion of treatment compared to baseline (Rompe 2004, Pettrone 2005). Levitt et al specified the primary endpoint as success/failure at 8 weeks with success defined as a minimum 50% improvement over baseline in investigator assessment of elbow pain, and a score no greater than 4 on VAS; and a minimum 50% improvement over baseline in self‐assessment of elbow pain, and a score no greater than 4 on VAS; and none or rare pain medication use (no more than 3 doses of pain medication) in the week prior to assessment.

All trials included pain scales but these varied between studies (0‐10 scale converted to 0‐100 scale for resting pain, pain at strain, Thomsen test, Mill test and midfinger test (Haake 2002);10 cm VAS for pain (Mehra 2003); 10 cm VAS for pain in a typical week and on lifting a 5 kg dumbbell (Melikyan 2003); 100 cm VAS for night pain, resting pain, pressure pain, Thomsen test, finger extension and Chair test (Rompe 1996); 10 cm VAS for pain during the day and night (Speed 2002); 10 cm VAS for overall pain, resting pain, pain during sleep, pain during the subject's main activity, pain at its worst, and pain at its least (Chung 2004); 10 or 100 mm VAS for pain elicited by the Thomsen test (Rompe 2004, Pettrone 2005); investigator assessment of pain at the point of tenderness over the affected lateral epicondyle on a 10 cm VAS and subject self‐assessment of pain during activity on a 10 cm VAS (Levitt 2004); and 0‐100 VAS for pain (Crowther 2002).

Speed et al determined the number of participants with 50% improvement from baseline at 1 month after the end of treatment (Speed 2002); Crowther et al determined the number of participants with at least 50% reduction of pain at 3 months after the end of treatment (Crowther 2002); Pettrone and McCall and Rompe et al determined the number of participants with at least a 50% improvement in pain elicited by the Thomsen test at 12 weeks (or 3 months) after the end of treatment (Pettrone 2005, Rompe 2004); Levitt et al determined the number of participants with at least 50% improvement over baseline at 8 weeks in both investigator and subject assessment of elbow pain which had to be combined with pain scores of no greater than 4 on VAS and none or rare pain medication use during the week prior to assessment (Levitt 2004); while Mehra et al calculated the number of participants who had improved by at least 3 points (on a 10‐point scale) from baseline at 6 months after the end of treatment (Mehra 2003).

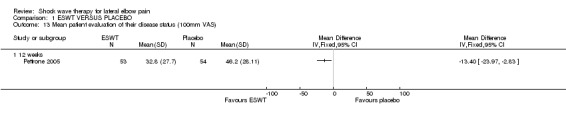

Six trials measured grip strength (Haake 2002; Melikyan 2003; Rompe 1996; Chung 2004; Rompe 2004; Pettrone 2005) although the methods varied between studies. Three studies used validated measures of function ‐ the Disabilities of Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH) (Hudak 1996b; Melikyan 2003) or the upper extremity functional scale (UEFS)(Pransky 1997; Rompe 2004; Pettrone 2005) although the UEFS was specifically developed to measure functional outcomes in work‐related upper extremity disorders. Three trials ( Rompe 1996; Haake 2002; Rompe 2004) used the Roles and Maudsley scale which combines assessment of pain and satisfaction with treatment into a 4‐point categorical scale (Roles 1972). Rompe et al measured overall satisfaction by asking participants whether they were able to perform activities at the desired level and to continue to play recreational tennis (Rompe 2004).One study used the thermometer subsection of the EuroQol 5D (EQ5D) quality of life instrument to assess quality of life (Chung 2004). Pettrone also used a 'patient‐specific activity score' by asking participants to identify two activities from the UEFS that they found particularly difficult to perform and rating their difficulty from 1 (no difficulty) to 10 (cannot perform); and an overall participant evaluation of their disease status on a 100 mm VAS (Pettrone 2005). Three studies measured analgesic use (Chung 2004; Melikyan 2003; Levitt 2004) and one study recorded the number of participants who proceeded to surgery (Melikyan 2003).

Overall, the studies were clinically homogeneous with respect to the duration of the disorder (apart from the trial by Chung and Wiley which included participants with a shorter duration of symptoms)(Chung 2004); type, frequency and total dose of ESWT and control group. However there was no uniformity in the timing of follow up and outcomes assessed, limiting the ability to pool data across studies. In addition, the majority of data in one trial was presented graphically without any measures of variance and this data was therefore unable to be included in the meta‐analyses (Melikyan 2003). Two other trials presented mean data without any measures of variance and this data was also unable to be included in meta‐analyses (Mehra 2003; Crowther 2002). Results of these trials are described in Additional Table 2 and 3 respectively.

Risk of bias in included studies

While all 10 trials were described as randomised, only five trials described their method of randomisation (Haake 2002; Mehra 2003; Crowther 2002; Rompe 2004; Chung 2004). Concealment of treatment allocation was adequate in two trials (Haake 2002; Chung 2004), adequate to 12 weeks following completion of treatment in one trial (Pettrone 2005); considered inadequate in one trial (Mehra 2003) and unclear in the remaining 6 trials (Melikyan 2003; Rompe 1996; Speed 2002;Crowther 2002; Rompe 2004; Levitt 2004).

Participants were reported to be blinded in 9 trials (Haake 2002; Mehra 2003; Melikyan 2003; Rompe 1996; Speed 2002; Chung 2004; Rompe 2004; Pettrone 2005; Levitt 2004) and assessment of outcome was blinded in 8 trials (Haake 2002; Melikyan 2003; Rompe 1996; Speed 2002; Chung 2004; Rompe 2004; Pettrone 2005; Levitt 2004). The trial comparing steroid injection to ESWT was not blinded (Crowther 2002). One trial unblinded all participants and outcome assessors at 12 weeks after the completion of treatment (Rompe 2004). Restrictions of treatment were lifted at this time and participants in the placebo group with persisting symptoms were offered active treatment. One trial also unblinded participants at 12 weeks after the completion of treatment if there had not been at least a 50% improvement in pain elicited by the Thomsen test compared to baseline (Pettrone 2005) Participants in the placebo group were also offered the active treatment at this time and outcome assessors were unblinded if participants received cross‐over treatment. It is not known whether unimproved participants in the active group (who were unblinded at 12 weeks) could receive additional treatment.

Five trials reported that the analysis was performed on the basis of intention to treat (Haake 2002; Speed 2002; Chung 2004; Rompe 2004; Pettrone 2005) although this could not be verified for one trial (Speed 2002) and in two trials a significant proportion of placebo patients received the active intervention after the 12‐week assessment (Rompe 2004; Pettrone 2005). One trial performed an intention to treat analysis although this was not stated explicitly in the report (Mehra 2003), two trials performed a completers analysis only (Rompe 1996; Melikyan 2003; Levitt 2004) and one trial included all randomised patients who completed treatment (Crowther 2002).

Four trials reported a sample size calculation (Haake 2002; Chung 2004; Rompe 2004Pettrone 2005). Haake et al had sufficient power (a=0.05, 1‐ß=0.8) to demonstrate a 20% difference in outcome of the primary endpoint (success rate at 12 weeks)(Haake 2002) and Chung and Wiley calculated that a sample size of 30 participants per group would have sufficient power (a=0.05, 1‐ß=0.8) to detect a 2‐fold difference in the proportion of treatment successes at 8 weeks (5 weeks after the completion of treatment), assuming that 20% of the placebo group would have a treatment success (i.e. 60% success rate in the active group), allowing for a 20% dropout/loss to follow up rate (Chung 2004). They considered that treatment successes in 60% of the ESWT group would constitute a clinically relevant and successful result. Rompe et al reported that a sample size of 35 patients per group would have >80% power in detecting a difference of 2 points in average pain rating to resisted wrist extension at the 3‐month assessment (i.e.. assuming pain is 5 ± 2 points in the placebo group, pain will be 3 ± 2 in the active group) with a 2‐sided significance level of 0.01 (Rompe 2004). Pettrone and McCall calculated that a sample size of 45 participants per group would provide sufficient power (a=0.05, 1‐ß=0.8) to demonstrate a 30% difference between the proportion of participants who improved by at least 50% from baseline to 12 weeks after the completion of treatment assuming a 50% success in placebo (80% success in active ESWT) and number were increased to 114 assuming a retention rate of at least 80% (Pettrone 2005).

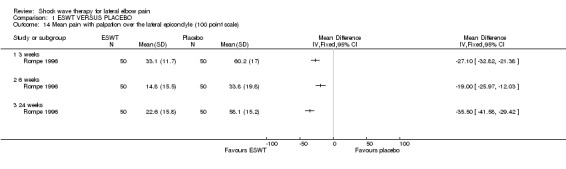

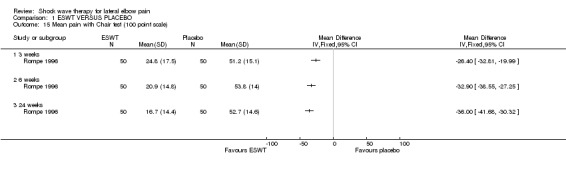

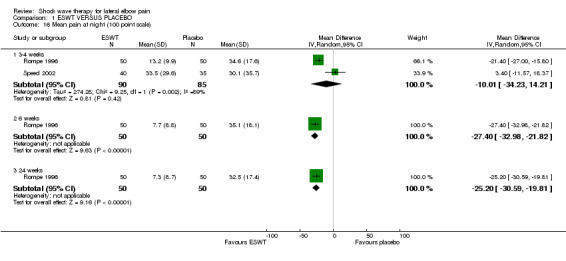

A summary of the methodological quality assessment for each of the trials is described below: Rompe et al have published 3 reports of a randomised placebo‐controlled trial of identical protocol investigating ESWT for lateral elbow pain (2 English and 1 German language publications performed at a single centre in Germany (Rompe 1996). One publication reports the results of 60 participants included over a two‐year period of whom 10 participants dropped out during the first 9 weeks (Rompe 1996). Follow‐up was reported for 12 weeks. These participants are included in the second and third publications that present data on 115 participants treated over a three‐year period (Rompe 1996; Rompe 1997). Fifteen participants were reported to discontinue treatment during the first 6 weeks and were not subsequently included in the analysis (drop‐outs 15/115 = 13%). Follow‐up was reported at 3, 6, 24 and 52 weeks. Only data from the latter two publications were included in the systematic review. The trial was reported to be randomised but the method of randomisation was not described and therefore it is unclear whether allocation concealment was adequate. Both the participants and outcome assessors were reported to be blinded to treatment allocation. The analysis was performed for completers of the trial only (n=100) and the treatment allocation of the 15 participants (13%) who dropped out was not reported.

Haake et al performed a multicenter randomised placebo‐controlled study in Germany and Austria including 271 participants (Haake 2002). It was reported to be single‐blind on the basis that the participants were blinded to intervention but the provider of the intervention was not blinded. However blinded outcome assessors were used. Allocation concealment was adequate. Randomisation occurred centrally by phone, using random permuted blocks of sizes 6 and 4 with separate randomisation lists for each centre. In a random sample of participants, 46.5% of those in the placebo group correctly identified their treatment allocation whereas 71.3% of participants in the active treatment group correctly identified their treatment allocation signifying differential success of blinding procedure between treatment groups. Intention to treat analysis was used, and loss to follow up was reported for 10 (7.5%) participants and 15 (10.9%) participants in the active and placebo groups respectively.

Speed et al performed a single centre randomised controlled trial in the UK including 75 participants (Speed 2002). The trial was reported to be randomised but the method of randomisation was not described and therefore it is unclear whether allocation concealment was adequate. Both participants and outcome assessors were reported to be blinded to treatment allocation. Follow up was reported 1 month after the completion of treatment (3 months from baseline). Four (5.3%) withdrew from the trial (2 in the active group after 2 treatments due to worsening symptoms and 2 in the placebo group for reasons which were unclear). Data was reported to be analysed on an intention to treat basis but it is unclear how missing data for the 4 participants who withdrew were handled in the analysis.

Mehra et al performed a randomised controlled trial in the UK including 24 participants with lateral elbow pain and 23 participants with plantar fasciitis (Mehra 2003). Treatment allocation concealment was inadequate with participants randomised by picking out a slip of paper (50 marked with 'T" for treatment and 50 marked with 'P' for placebo) from a box. The slips of paper were replaced in the box after each randomisation. Participants were reported to be blinded and outcome assessment was unblinded. No loss to follow up was reported and although not explicitly stated, it appears that an intention to treat analysis was performed. Results for lateral elbow pain and plantar fasciitis were reported separately allowing inclusion in this review.

Melikan et al performed a randomised controlled trial in the UK including 86 participants (Melikyan 2003). The trial was reported to be randomised but the method of randomisation was not described and therefore it is unclear whether allocation concealment was adequate. Both participants and outcome assessors were reported to be blinded to treatment allocation. Eleven participants did not complete a full course of treatment and an additional participant did not attend for follow up (12/86 14%). These 12 participants were not included in the efficacy assessment and a completers only analysis was performed. Crowther et al performed a randomised controlled trial in the UK including 93 participants (Crowther 2002). Patients in the trial were randomised using closed unmarked envelopes. It is unclear whether allocation concealment was adequate. It appears that the patients were not blinded and it is not stated whether outcome assessment was blinded. Three of 51 (5.9%) participants randomised to ESWT withdrew prior to completion of treatment and 17/52 (32.7%) participants randomised to steroid injection refused participation after randomisation. It is unclear whether there were any participants lost to follow up after treatment completion although analysis of reduction of pain of 50% as a criterion of success at 3 months after the end of treatment included all patients who were randomised and completed treatment. Chung and Wiley performed a randomised controlled trial in Canada including 60 participants (Chung 2004). Trial participants were randomised according to block randomisation with random block sizes of 2, 4 and 6, stratified according to whether subjects had one or both elbows affected. Numbered opaque envelopes were used to conceal allocation and these were opened by the ESWT technician at the time of the first treatment. All participants and outcome assessor was blinded to treatment allocation. Participants were not aware that there was a placebo treatment but were informed the study was comparing two different therapy protocols. The authors stated that this deception was performed to preserve subject blinding because of widespread accessibility of information on ESWT protocols, in particular information regarding discomfort during therapy. Ethical approval was granted by the Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board at the University of Calgary. Four participants (6.7%) were lost to follow up (2 participants (1 in each group) did not attend the 8‐week follow‐up; 1 participant in the placebo group did not attend for therapy (and so presumably did not provide any post‐baseline data; and 1 participant also in the placebo group is stated to have not noted any improvement but it is not clear whether this participant provided any post‐baseline data.). Analysis was according to intention to treat with last observation carried forward used for missing outcome data.

Rompe et al performed a second randomised controlled trial in Germany including 78 participants, all of whom were recreational tennis players with symptoms for at least 12 months (Rompe 2004). Trial participants were randomised according to a computer‐generated random numbers list and only the person performing the intervention knew the treatment allocation. Both participants and outcome assessors were blinded up until the 3‐month assessment but were unblinded at this timepoint. Participants in the placebo group with persisting symptoms were then offered active ESWT and 24/40 (60%) subsequently received active treatment. Eight participants (10.3%) did not provide 3‐month data: 2 participants in the active group were lost to follow up and another 2 participants in the active group reported good outcome by telephone but did not attend the 3‐month assessment due to lack of time; 4 participants in the placebo group were withdrawn prior to the 3‐month assessment due to violation of protocol (3 had received NSAIDs and 1 had received an injection). A further 6 participants (3 in each group) were lost to follow up for the 12‐month assessment (refusal of follow up (2 participants in the placebo group and 1 in the active group; 2 in the active group were lost to follow up and 1 in the placebo group had travelled overseas). Assessment of participants' blindness was performed immediately after the last ESWT treatment and 22/40 (55%) of those in the placebo group correctly identified their treatment allocation whereas 29/38 (76.3%) of participants in the active treatment group correctly identified their treatment allocation signifying differential success of blinding procedure between treatment groups which may have influenced the outcome. Analysis was according to intention to treat with last observation carried forward used for missing outcome data. In view of the unblinding of all participants after the 12‐week assessment, crossover of placebo participants to the active group and no description of what additional treatments may have been used by unimproved participants in the active group after the 12‐week blinded assessment, results after 12 weeks need to be interpreted cautiously and are not presented in this review.

Pettrone and McCall performed a randomised controlled trial in 3 centres in the USA including 114 participants (Pettrone 2005). While the method of randomisation was not described, it appeared that treatment allocation concealment was adequate as at randomisation each participant was given a unique study number and a sealed envelope with their study number on it. The sealed envelope contained the randomisation code (A or B) which was only opened by the shock wave operator and not shared with anyone else in the study. All participants and outcome assessors were blinded to treatment allocation up to 12 weeks following the completion of treatment. Six participants (5.3%) (3 in each group) withdrew before the 12‐week assessment (2 in the active group due to treatment intolerance (these participants did not complete the 3‐week course of treatment) , 1 in the active group due to preexisting thrombocytopenia, and 3 in the placebo group to seek alternative treatment). Analysis was according to intention to treat with last observation carried forward used for missing outcome data. At the 12‐week assessment, if there had not been at least a 50% improvement in pain elicited by the Thomsen test compared to baseline, the treatment code could be broken. This applied to 38/58 participants (66%) in the placebo group and 19/56 participants (34%) in the active ESWT group. 34/38 participants (89.5%)in the placebo group subsequently received active ESWT and these participants were openly followed for a further 12 weeks but were considered lost to the placebo group. If the participant had failed the active treatment, other standard therapies could be given. Following the 12‐week assessment, 17/56 (30.4%) and 34/58 (58.6%) participants in the placebo and active treatment groups respectively were still blinded. At the 6‐ and 12‐month assessments, 16 (27.6%) and 15 (25.9%) still blinded participants in the placebo group were assessed respectively. At the 6‐month assessment, 28 (50%) still blinded participants in the active group were assessed (6 were lost to follow up between the 12‐week and 6‐month assessments). The number of blinded participants in the active treatment group at the 12‐month assessment and their assessment was not provided. Results were also provided for the combined blinded and unblinded participants in the active treatment group at the 6‐ and 12‐month assessments (47 and 46 participants respectively), although the results for the 19 unblinded participants could have also been influenced by additional therapies (not described). In view of the high proportion of participants unblinded after the 12‐week assessment, cross‐over of placebo participants to the active group, diminishing numbers of blinded participants available for analysis over time and the possibility of cointervention in the unblinded active group, results after the 12‐week blinded assessment need to be interpreted cautiously and are not presented in this review. Levitt et al performed a multicenter randomised controlled trial in the USA including 183 participants (Levitt 2004). The number of sites and the method of randomisation was not described. All participants and outcome assessors were blinded to treatment allocation. A minimum of two investigators participated in the study at each site: one investigator served as the blinded evaluator and the other performed the study procedures. Data for 19 (10.4%) participants (9 in the active group and 10 in the placebo group) were not included in the 4‐week assessment and 18 (9.8% )participants (11 in the active group and 7 in the placebo group) were lost to follow up or withdrawn prior to the 8‐week assessment. A completers only analysis was performed.

Effects of interventions

EFFICACY ESWT VERSUS PLACEBO The 9 placebo‐controlled trials included in this updated review reported conflicting results. Three trials reported significant differences in favour of ESWT for all or most measured endpoints (Rompe 1996; Rompe 2004; Pettrone 2005), whereas four trials reported no benefits of ESWT over placebo for any of the measured endpoints (Haake 2002; Speed 2002; Melikyan 2003; Chung 2004). A fifth (unpublished) trial reported a statistically significant difference in the primary composite endpoint of significant improvement in investigator and subject assessed pain and rare use of pain medications however this appeared to be a completers only analysis and when an intention to treat analysis was performed this result was no longer significant (33/93 (35.5%) and 20/90 (22.2%) in the ESWT and placebo groups respectively, p=0.07)(Levitt 2004); and benefit was only demonstrated for investigator assessed pain at 8 weeks. An additional small trial of 24 participants reported benefit (e.g.. 10/13 participants significantly improved by 3 or more points (on a 10 point pain scale) at 6 months in comparison to 1/11 participants in the placebo group) but this could not be verified from the data presented (Mehra 2003).

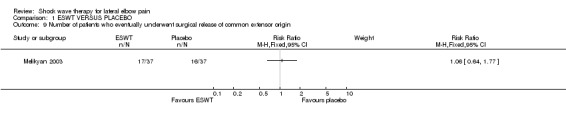

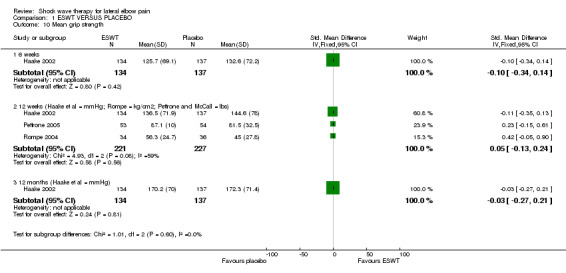

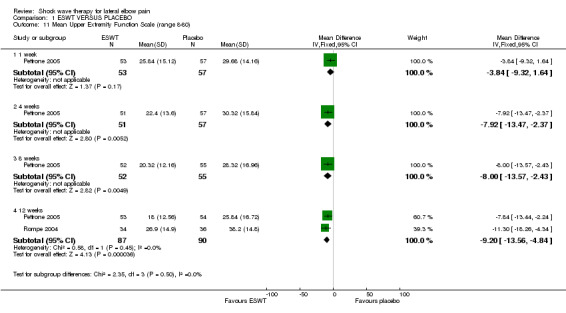

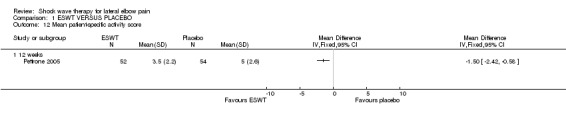

When available data from the trials were pooled, most benefits observed in the positive trials were no longer statistically significant. Data from 6 trials could be pooled and based upon this data most of the evidence supports the conclusion that ESWT is no more effective than placebo for lateral elbow pain. For example, pooled analysis of three trials (446 participants)(Haake 2002; Rompe 1996; Speed 2002) showed that ESWT is no more effective than placebo with respect to pain at rest at 4 to 6 weeks after the final treatment [WMD pain out of 100 = ‐9.42 (95% CI ‐20.70 to 1.86)]; pooled analysis of three trials (455 participants)(Haake 2002; Rompe 2004; Pettrone 2005) showed that ESWT is no more effective than placebo at 12 weeks after the final treatment with respect to pain provoked by resisted wrist extension (Thomsen test) [WMD pain out of 100 = ‐9.04 (95% CI ‐19.37 to 1.28)] and grip strength [SMD 0.05 (95% CI ‐0.13 to 0.24)]. However, pooling of two positive trials (192 participants) (Rompe 2004; Pettrone 2005) did demonstrate a benefit for ESWT over placebo with respect to success of treatment, defined as at least a 50% improvement in pain with resisted wrist extension at 12 weeks following completion of treatment (RR 2.2 (95% CI 1.55 to 3.12), while four other individual trials with well‐defined criteria for success at 4 to 12 weeks, that were unable to be pooled, failed to find evidence of benefit of ESWT (Speed 2002; Haake 2002; Chung 2004; Levitt 2004). Pooling the results of the same two positive trials also showed a statistically significant benefit for ESWT over placebo for function as measured by the UEFS [WMD ‐9.20 (95% CI ‐13.56 to ‐4.84)] (Rompe 2004; Pettrone 2005) although the clinical significance of this finding is not known. Pooled analyses combining results of other trials failed to demonstrate statistically significant benefits for ESWT over placebo across a range of outcomes including mean pain with resisted middle‐finger extension or resisted wrist extension at 6 weeks following completion of treatment, night pain at 3‐4 weeks following completion of treatment or failure of treatment defined by a Roles and Maudsley score of 4 at 6 weeks and 12 months following completion of treatment. (Speed 2002; Haake 2002; Chung 2004; Levitt 2004). Based upon the results of one small trial, there was no difference in the number of participants who eventually underwent surgical release of the common extensor origin following treatment in one trial [17/37 in the ESWT group and 16/37 in the placebo group, relative risk = 1.06 (95% CI 0.64, 1.77] (Melikyan 2003). The timing of surgery in relation to the trial was not specified.

ESWT VERSUS STEROID INJECTION One trial reported that steroid injection was more effective than ESWT at 3 months after the end of treatment assessed by a reduction of pain of 50% from baseline as the criterion of success (21/25 (84%) versus 29/48 (60%), p<0.05). Mean pain scores at 6 weeks after the end of treatment also favoured steroid injection although measures of variance were not reported (mean pain (on a 0‐100 scale) at baseline and 6 weeks was 67 and 21 in the steroid injection group and 61 and 35 in the ESWT group, p = 0.052). At 3 months after the end of treatment, mean pain scores also favoured steroid injection (12 and 31 in the steroid injection and ESWT groups respectively).

ADVERSE EFFECTS Four trials reported no significant adverse effects in either treatment groups (Rompe 1996; Speed 2002; Melikyan 2003; Crowther 2002). One trial documented significantly more side effects in the ESWT group (OR 4.3, 95% CI 2.9 to 6.3) (Haake 2002). However there were no treatment discontinuations or dosage adjustments related to adverse effects. The most frequently reported side effects in the ESWT treated group were transitory reddening of the skin (21.1%), pain (4.8%) and small haematomas (3.0%). Migraine occurred in 4 participants and syncope in 3 participants following ESWT. Mehra et al (Mehra 2003) reported that 8 participants complained of increased pain and four participants reported localised redness during treatment although the condition being treated (lateral epicondylitis or plantar fasciitis) and the treatment group (ESWT or placebo) was not specified. Chung et al reported mild adverse events in 11 participants (35.5%) in the ESWT group and 13 participants (46.1%) in the placebo group ( tingling during therapy (5 participants in the placebo group), nausea during therapy (3 participants in the ESWT group), achiness after therapy (1 participant in each group), soreness after therapy (3 participants in the ESWT group and 4 participants in the placebo group) and increased pain symptoms after therapy (4 participants in the ESWT group and 3 participants in the placebo group)(Chung 2004). Pettrone and McCall reported no serious adverse device effects (Pettrone 2005). However 28 (50%) and 13 (22.4%) participants in the active and placebo groups respectively experienced transient moderate treatment related pain; and 10 (17.9%) participants in the active group experienced nausea during the treatment. Two participants in the active group had to stop treatment sessions prior to receiving the full 2000 impulses because of nausea: one of these participants subsequently withdrew from the study and the other was able to resume and tolerate the treatment later. An additional participant in the active group withdrew after completing the first treatment due to pain and a slight tremor in the treated arm. All side effects resolved. Rompe et al reported temporary reddening after low‐energy shock wave application in all patients (Rompe 2004). Pain during treatment occurred in 36/38 (94.7%) and 21/40 (52.5%) of active ESWT and placebo participants respectively; and nausea during treatment occurred in 8/38 (21.1%) and 1/40 (2.5%) of active ESWT and placebo participants respectively. All side effects had resolved by final follow‐up. Levitt et al reported localised swelling, bruising, or petechiae at the treatment site (n=19) and reactions to anaesthetic agents (n=9) however all anaesthetic reactions occurred at a single site and may have been related to the method of administering a regional block (Levitt 2004).

Discussion

Nine placebo‐controlled trials including 1006 participants, and reporting conflicting results, were included in this systematic review. Data from six trials could be pooled and based upon this data most of the evidence supports the conclusion that ESWT is no more effective than placebo for lateral elbow pain. While three trials reported highly significant differences in favour of ESWT, these results became non‐significant when combined with the results of studies that reported no or minimal benefit of ESWT over placebo. Eleven of the 13 pooled analyses found no benefit of ESWT over placebo while 2 pooled analyses that did show a benefit included 2 positive trials. The positive pooled results for treatment success were not supported by the results of four other individual trials that were unable to be poole. The inclusion of the two trials that were unable to be included in the meta‐analysis would not have altered the overall findings of this review and an additional trial that studied untreated participants with lateral elbow pain also supported the findings of a lack of benefit of ESWT (Chung 2004).

The results of this systematic review are similar to the findings of a systematic review of ESWT for plantar heel pain (Thomson 2005). Meta‐analysis of data from the 4 high quality RCTs found no evidence of benefit of ESWT. The discrepancy in the results between the positive and negative trials in our review may also be explainable on the basis of differing trial quality. The largest negative trial (271 participants) was of high quality with a valid randomisation method, adequate concealment of treatment allocation, blinding of participants and outcome assessors, and intention to treat analysis. It reported both a prespecified primary endpoint and sample size calculation (Haake 2002). The second negative trial (75 participants) did not report their method of randomisation, but did blind both participants and outcome assessors, reported a prespecified primary endpoint and performed an intention to treat analysis although it is not clear whether it was adequately powered to detect a clinically important difference between groups as no sample size calculation was reported (Speed 2002). Of the three positive trials, one trial (115 participants) did not report their method of randomisation and performed a completers analysis only (Rompe 1996). The other two positive trials allowed either all patients to be unblinded at 12 weeks (Rompe 2004) or unblinding at 12 weeks for those without an adequate response (Pettrone 2005). In both trials, placebo patients were also offered cross‐over into the active group at 12 weeks and unblinded patients were allowed additional therapy. Therefore reported results after 12 weeks in both trials should be interpreted cautiously.

Due to inadequate reporting of results, two placebo‐controlled trials published in 2003 did not contribute data to the meta‐analysis. Results of one of the two additional trials (86 participants) supports the conclusion of the pooled analysis (Melikyan 2003), while the second trial (24 participants) reported a significant benefit in favour of ESWT (Mehra 2003). In view of the small size of the second trial, it is unlikely that it would have significantly altered the results of the meta‐analysis if data were available for pooling. Two recent trials also elected to unblind either all participants or those who were unimproved at 12 weeks after completion of treatment and offer cross‐over into the active group for those placebo participants who were unimproved (Pettrone 2005; Rompe 2004). Restriction on other treatments was also lifted at this time although whether additional treatments were received by unimproved participants in the active group was not reported. Due to a diminished number of blinded participants, and the possibility of confounding of any treatment effects it was not possible to interpret the longterm results of these trials.

This review also included one trial comparing steroid injection to ESWT which demonstrated a benefit of steroid injection over ESWT at 3 months with respect to 50% reduction of pain (Crowther 2002). This is consistent with previous findings from one systematic review and subsequent randomised controlled trials of corticosteroid injections for lateral elbow pain which have found limited evidence of a short term improvement in symptoms with steroid injections compared with placebo, a local anaesthetic, orthoses (elbow strapping), physiotherapy, or oral non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (Assendelft 1996; Assendelft 2003).

We found a lack of uniformity in both the timing of follow up and the outcomes that were measured. All studies measured pain with some including varying aspects of pain (e.g.. pain with activities and at different times). Three trials used the Roles and Maudsley scale which incorporates both pain and an assessment of whether pain limits activities into a 4‐point categorical scale (Haake 2002; Rompe 1996; Rompe 2004) although Rompe et al analysed the results as a continuous rather than categorical data (Rompe 2004). Three trials included an upper‐arm specific disability measure (the DASH)(Melikyan 2003) or the UEFS (Pettrone 2005; Rompe 2004) and no trial included a generic quality of life instrument (although information from the FDA report of one unpublished trial suggested that the SF‐36 may have been administered although no results were presented)(Levitt 2004). An international consensus for the use of a standard set of outcome measures in clinical trials for lateral elbow pain that are valid, reliable and sensitive to change would improve our ability to interpret and compare the results of different studies. These might include overall pain with or without provocation, a measure of upper extremity function (such as the UEFS), ability to carry out usual activities, work and/or sport, and possibly also a measure of quality of life. To facilitate judgement about clinically important differences between treatment groups, it would also be useful to have consensus about what constitutes a clinically important improvement. Future trials could then report the proportion of participants who obtain a clinically important improvement in the groups being compared.

There continues to be considerable debate relating to the use of shock wave therapy in soft tissue musculoskeletal complaints, as evident by the lively 'Letter to the Editor' and 'Authors' reply" correspondence that seems to follow the publication of each new ESWT trial in the musculoskeletal field. Issues under contention continue to include the optimal shock wave treatment regimes; dosing intervals; and whether focussing of ESWT to the site of pathology can be improved by fluoroscopy or ultrasound. Some experts argue that the shock waves should be focussed to the site of maximal tenderness as determined by the patient and imaging may result in errors in localisation of the pathology; whereas the contrary view is that imaging, together with clinical input from the patient may improve the accuracy and therefore the efficacy of ESWT. In our view, both methods are probably valid as each would more than likely direct the focus of ESWT to the site of maximal pathology. Studies that directly compare one machine to another or compare dosing intervals etc. may be able to determine whether there are any differences in outcome. One trial has compared two different ultrasound localising techniques and reported no difference in outcome (Melegati 2004).

A second, related point of difference, is whether imaging such as ultrasound or MRI has a role in establishing the presence of pathology at the site of tendon insertions such as the common extensor origin in patients with lateral elbow pain. For example the recent trial by Rompe et al required a positive MRI (increased signal intensity of extensors) for study inclusion (Rompe 2004). We have also previously used ultrasound to confirm the presence of plantar fasciitis in a trial of ESWT for plantar heel pain (Buchbinder 2002). This may increase the homogeneity of the study population, increase the likelihood of being able to demonstrate benefit of a new therapy if one exists and enable valid comparisons to be made between studies. Another area of contention is the use of local anaesthetic with opponents of its use arguing that local anaesthetic may have detrimental effects on the outcome of ESWT and in addition the patient is unable to verify that the correct site has been targeted when the areas has been anaesthetised.

All trials included in this review reported improvement in outcome in both the treated and non‐treated populations. These observed treatment effects might be explained on the basis of placebo effects related to participating in a trial or the self‐limiting natural history of the condition. Proponents of ESWT, highlighting the favourable natural history of this condition with its high rate of spontaneous improvement, have asserted that this treatment should be reserved for patients with chronic recalcitrant cases that have failed to respond to a multitude of other conservative treatments such as NSAIDs, corticosteroid injections, orthotics and physiotherapeutic modalities. Yet the evidence as presented in this review to support this approach is limited. Furthermore the trial by Chung and Wiley failed to find any evidence of benefit of ESWT for patients with symptoms of lateral elbow pain for between 3 weeks and a year who had not previously been treated (Chung 2004). We have also previously been unable to demonstrate any differential effect of duration of symptoms on outcome from ESWT in a trial for plantar fasciitis (Buchbinder 2002). At this time, the outcome of ESWT appears to be similar irrespective of duration of symptoms and/or receipt of prior treatment.

New effective interventions for the treatment of lateral elbow pain are needed and these should be evaluated in high quality RCTs prior to their routine clinical use. Their cost‐effectiveness should also be assessed. Placebo effects of treatment and the fact that lateral elbow pain is a self‐limiting condition also needs to be taken into consideration when planning and interpreting the results of RCTs.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

There is evidence based upon a systematic review of nine placebo‐controlled trials involving 1006 participants and meta‐analyses of up to three trials, that ESWT has minimal benefits compared to placebo for lateral elbow pain. While four trials reported significant differences in favour of ESWT, five trials reported little or no benefit of ESWT over placebo. When available data from trials were pooled, most benefits observed in the positive trials were no longer statistically significant. There did not appear to be any differences in outcome for participants early or late in the course of their condition or between different modes of delivery of ESWT. There is limited evidence based upon a single trial of 93 participants, that steroid injection may be more effective than ESWT. ESWT may be associated with transient adverse effects including pain, nausea and local reddening. This systematic review does not support the use of ESWT for lateral elbow pain in clinical practice.

Implications for research.

New effective interventions for the treatment of lateral elbow pain are needed and these should be properly evaluated in high‐quality RCTs prior to their use in routine clinical care. Also, because several recent trials of ESWT were poorly reported we suggest that authors of trials use the CONSORT statement as a model for reporting of RCTs (www.consort‐statement.org). Trial reporting should include the method of randomisation and treatment allocation concealment, follow up of all participants who entered the trial, and an intention to treat analysis. Sample sizes should be reported and have adequate power to answer the research question, and for chronic pain, ideally trials should include both short‐term and long‐term follow‐up. To enable comparison and pooling of the results of RCTs, we suggest that future trials report means with standard deviations for continuous measures or number of events and total numbers analysed for dichotomous measures. Development of a standard set of outcome measures including a definition of what constitutes a clinically important improvement for lateral elbow pain, would significantly enhance these research endeavours.

Feedback

Comment April 2007

Summary

Phil Jiricko Date received: April 20, 2007

While I agree with the general idea that the ESWT literature is confusing at best, this meta‐analysis is not an accurate representation of the synthesis of the literature to date. At its essence a meta‐analysis is only as good as the homogeneity of the individual research. One cannot combine a trial of 5000mg 10 times a day of acetaminophen with one of 500mg 4 times a day and have any sound conclusion. Unfortunately, this meta‐analysis combines several different protocols.

First, those who perform repetitive low energy shock wave therapy understand that the only focusing method that works is referred to as "clinical focusing". That means one delivers a set amount of shocks to the area (s) of maximal tenderness for the patient (often more than one focused spot). This requires constant feedback from the patient and movement of the shock focus throughout the treatment time. It is IMPOSSIBLE to deliver accurate targeting of shock waves either by ultrasound guidance or if the patient is anesthetized. It must be performed by CONSTANT FEEDBACK from the patient. The trials by Crowther 2002, Haake 2002, Melikyan 2003, and Mehra 2003 either used anesthesia or ultrasound guidance. One cannot compare these with the other trials that used a clinical focusing, non‐anesthetic model. These are simply not the same protocol and I would expect poor results.

The natural history of most lateral epicondylitis is improvement over the first 6 months regardless of treatment (1). ESWT was designed as a pre‐surgical option for chronic (greater than 6 months) conditions. Chung 2004 took patients that had symptoms for 3 weeks and Speed looked at patient with only 3 mos of symptoms. We know that a significant amount of those in the placebo arm will get better in the first 6 months, regardless of treatment, making the difference between the treatment and placebo arm indistinguishable.

Speed 2002 also took the unique approach of monthly intervals between treatment session. Different than all the other protocols!

Is it not surprising then that the consistent protocols followed by Pettron 2005, Rompe 2004, and Rompe 1996 all used clinical focusing, on a standard interval, in patients with symptoms for 6 mos or greater, actually had significant differences? The protocol followed by these authors is efficacious.

Meta‐analysis should be reserved for trials that have established and homogeneous protocols. This analysis falls far from that tree and should be re‐examined.

1: Lancet. 2002 Feb 23;359(9307):657‐62. Corticosteroid injections, physiotherapy, or a wait‐and‐see policy for lateral epicondylitis: a randomised controlled trial. Smidt N, van der Windt DA, Assendelft WJ, Deville WL, Korthals‐de Bos IB, Bouter LM.

Phil Jiricko MD MHA MS Occupational Medicine University of Utah

Reply

April 30, 2007 We consider our systematic review to be an accurate representation of the synthesis of the literature to date. We performed a rigorous assessment of the methodological quality of the included trials. We also described in detail the variety of devices used to generate shock waves, the various dosing regimens, the methods used to focus the shock waves, dosing intervals and use of local anaesthesia. Additional table 1 summarises these details for each trial. The time intervals between treatment sessions varied from a single treatment to 3 treatments at weekly, fortnightly and monthly intervals.

As described in our methods, meta‐analysis or pooling of data from different trials was only performed if we judged the trials to be clinically homogeneous. Clinical homogeneity was assessed based upon duration of the disorder, type, frequency and total dose of ESWT, control group and the outcomes. Clinically heterogeneous studies were not combined in the analysis, but separately described. Furthermore, for studies judged as clinically homogeneous, statistical heterogeneity was tested by Q test (chi‐square) and I2. Clinically and statistically homogeneous studies were pooled using the fixed effects model. Clinically homogeneous and statistically heterogeneous studies were pooled using the random effects model.

We are unaware of any published data concerning the validity of using the site of maximal tenderness to guide focusing of the shock wave or of any published data verifying that the site of maximal tenderness is the site of pathology. Similarly we are unaware of any published data concerning what effect, if any, use of local anaesthesia has on the outcome. To our knowledge there is no evidence to suggest that one method of focusing the shock wave is superior to another method. We know of only one study that has compared methods for focusing or targeting the delivery of the shock wave for lateral elbow pain (1). This trial compared two ultrasonic focusing techniques and found no difference in outcome.

As we stated in the discussion of our review, some studies have used ultrasound guidance to enhance clinical focusing (not replace it) by also ensuring that the site of pathology is targeted. Whether this influences the outcome remains uncertain. Many studies have found that imaging improves the accuracy of interventions such as steroid injections for joint and soft tissue injections (2). This may be associated with better outcomes although evidence for the latter is still limited particularly for longer term outcomes sufficient to justify the extra cost (2). For example, two randomised trials have found that pain relief from ultrasound‐guided steroid injection was no different to blind injection in plantar fasciitis (3, 4) although one trial reported a lower recurrence rate (4).