Abstract

BACKGROUND

Bipolar disorder (BD) is a severe psychiatric disorder characterized by mood swings. Psychosocial interventions, such as psychoeducation, play an essential role in promoting social rehabilitation and improving pharmacological treatment.

AIM

To investigate the role of psychoeducation in BD.

METHODS

A systematic review of original studies regarding psychoeducation interventions in patients with BD and their relatives was developed. A systematic literature search was performed using the Medline, Scopus, and Lilacs databases. No review articles or qualitative studies were included in the analysis. There were no date restriction criteria, and studies published up to April 2021 were included.

RESULTS

A total of forty-seven studies were selected for this review. Thirty-eight studies included patients, and nine included family members. Psychoeducation of patients and family members was associated with a lower number of new mood episodes and a reduction in number and length of stay of hospitalizations. Psychoeducational interventions with patients are associated with improved adherence to drug treatment. The strategies studied in patients and family members do not interfere with the severity of symptoms of mania or depression or with the patient's quality of life or functionality. Psychoeducational interventions with family members do not alter patients' adherence to pharmacotherapy.

CONCLUSION

Psychoeducation as an adjunct strategy to pharmacotherapy in the treatment of BD leads to a reduction in the frequency of new mood episodes, length of hospital stay and adherence to drug therapy.

Keywords: Bipolar disorder, Mood disorders, Psychoeducation, Adherence, Mania, Depression

Core Tip: Bipolar disorder (BD) is a severe and chronic psychiatric disorder that requires intense treatment usually based on pharmacotherapy. Treatment applying psychotherapy adjunctive treatment is usually prescribed, although with inconsistent data. We aimed to perform a systematic review evaluating the evidence of psychoeducation in BD patients and their family members. Evidence suggests that psychoeducation of patients and family members is associated with a lower number of new mood episodes and a reduction in number and length of stay of hospitalizations. Psychoeducational interventions with patients are associated with improved adherence to drug treatment. Psychoeducation is a good interventional strategy for BD treatment.

INTRODUCTION

Bipolar disorder (BD) is a chronic mental health illness characterized by mood swings[1]. It is estimated that more than 1% of the world population is affected by BD[2,3]. The prevalence rates for each BD subtype, I and II, in community-based samples are 0.6% and 1.4%, respectively, and the mean age of onset of the disease is approximately 20 years[2,3]. Poor treatment adherence is associated with mood swings, social stigmatization, and lower social support in BD[4]. Psychosocial interventions might play an essential role in promoting social rehabilitation and improving pharmacotherapy adherence. Studies have demonstrated that non-pharmacological interventions, such as psychoeducation and cognitive-behavioral and interpersonal therapy, promote effects in the treatment of acute mood episodes and maintenance treatment in BD[5]. These actions favors the early recognition of warning signs of mood instability and promote the development of healthier lifestyles[4].

Psychoeducation is an intervention strategy based on providing patients and/or relatives with information about the disorder to enhance their understanding and enable early identification of warning signs and mood changes, improving treatment adherence[5-7]. Psychoeducational strategies in BD might promote the frequency of new mood episodes and medication adherence[8]. The Barcelona Psychoeducation Program was associated with an almost ninefold decrease ratios regarding new mood episodes and reduced the number of symptomatic days, as well as the hospitalization’s length of stay (LOS)[9]. Family psychoeducation intervention has been correlated with mood episode reduction in patients with BD[7]. When family members acquire better knowledge about the disorder, they contribute to the early detection of the first symptoms of changes in mood[10,11].

This systematic review aims to investigate the role of psychoeducation in BD in patients and in their family members.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Search strategies and selection criteria

The authors have read the PRISMA 2009 Checklist, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the PRISMA 2009 Checklist. A systematic literature search was performed through the Medline (Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online/PubMed), Scopus and Lilacs databases. Studies published up to April 2021 were included. The key terms used were “bipolar disorder” and “psychoeducation”. Studies in Portuguese and English were selected. Two independent reviewers (J.L.R. and I.G.B) analyzed the titles and abstracts; afterward, texts that fulfilled the requirements were included. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Original psychoeducation intervention studies; (2) Placebo-controlled studies; and (3) Interventions aimed at adult patients with BD. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Review, case series, and case report; (2) Interventions aimed at groups of patients with other mental or behavioral disorders; (3) Book chapters or reviews, systematic reviews or meta-analyses; (4) Studies written in languages other than English or Portuguese; (5) Low-quality studies according to the Newcastle–Ottawa scale (NOS) scale; and (6) Interventions aimed at children or adolescent patients with BD. Only original studies with a control group or baseline data for psychoeducation interventions in patients with BD and their relatives were included.

Data extraction and quality assessment

The systematic review has been registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) with registration number CRD42020168910.

We developed a data extraction table based on a Cochrane model[12]. One of the revisors (J.L.R.) extracted data and another (I.G.B) verified them. To reduce selection bias, two revisors (J.L.R. and I.G.B.) assessed the methodological quality of all the studies according to the NOS criteria[13]. The NOS is a "star system"-based scale, which scores a maximum of 4 stars corresponding to selecting studying groups, 3 stars for the ascertainment of either the exposure or outcome of interest, and 2 for the comparability of the groups; thus, the total NOS maximum score is 9. In the present study, we considered a minimum score of 5 on the NOS scale sufficient to be included[13]. In the circumstances of any disagreement between those 2 revisors, a third revisor was consulted (B.F.C) for consensus.

All extracted data included information about publication (including author name and year of publication), some group characteristics (sample size, gender, mean age, mood state and subtype of BD), methods (psychoeducation protocols; number of sessions; instruments that were applied, and who had performed them; kind of study, either a blinded or a randomized one) and their main outcomes.

RESULTS

Description of studies

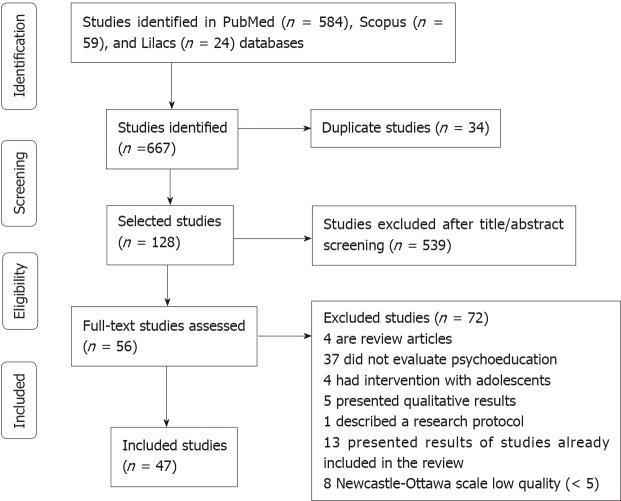

Six hundred sixty-seven publications were identified from the literature search (PubMed: Five hundred and eighty-four; Scopus: Sixty-one and Lilacs: Twenty-four). Duplicated studies were excluded (n = 34). Five hundred thirty-nine were excluded after title and abstract screening. Twenty studies were included from manual extraction. Seventy-two studies were excluded: Four of these were article reviews; thirty-seven did not include psychoeducation treatment; four were about intervention strategies in patients under 18 years of age; five studies were qualitative studies; one study was about a protocol; and thirteen studies were duplicated. Eight studies were classified as low quality according to the NOS scale (i.e., scored less than or equal to five stars) and were excluded from the present manuscript. A total of forty-seven publications were selected for this review, of which thirty-eight studies included patients with BD and nine studies included relatives of patients with BD (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for studies evaluating psychoeducation in bipolar disorder.

Characterization of included studies

Studies in patients with BD: Thirty-eight clinical studies were included. Thirty-eight studies[6,8,11-46] scored five or more stars according to the NOS scale[12] (Table 1). There were thirty-three randomized studies[6,8,11-18,20-26,28-32,34-36,39-47] and five nonrandomized studies[19,27,33,37,38]. Eighteen studies included euthymic or remitted patients[6,8,11,16-21,25,26,28,33,35,37,41-43]. Two studies included patients with depressed mood[31,32]. Sixteen publications did not evaluate the mood episodes of the patients[12-15,22-24,27,29,30,34,36,38-40,44].

Table 1.

Newcastle–Ottawa scale evaluation for studies that assessed psychoeducation in bipolar disorder patients

|

Ref.

|

Representativeness of the exposed cohort

|

Selection of the non-exposed cohort

|

Ascertainment of exposure

|

Demonstration that outcome of interest was not present at start of study

|

Comparability of cohorts on the basis of the design or analysis

|

Assessment of outcome

|

Follow-up long enough for outcomes to occur

|

Adequacy of follow up of cohorts

|

Total

|

| Zhang et al[14], 2019 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Wiener et al[15], 2017 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Cardoso et al[16], 2015 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Cardoso et al[17], 2014 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Faria et al[18], 2014 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Kurdal et al[19], 2014 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Javadpour et al[20], 2013 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| de Barros Pellegrinelli et al[21], 2013 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Candini et al[22], 2013 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Colom et al[11], 2009 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Colom et al[23], 2003 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 10 |

| Colom et al[24], 2003 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Dalum et al[25], 2018 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Depp et al[26], 2015 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Lauder et al[27], 2015 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Torrent et al[28], 2013 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Smith et al[29], 2011 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Sylvia et al[30], 2011 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 6 |

| D'Souza et al[31], 2010 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Castle et al[32], 2010 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| So et al[46], 2021 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Sajatovic et al[33], 2009 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Miklowitz et al[34], 2007 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| Miklowitz et al[35], 2007 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| González Isasi et al[36], 2014 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Parikh et al[37], 2012 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Zaretsky et al[38], 2008 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Proudfoot et al[39], 2012 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Aubry et al[40], 2012 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 6 |

| Gonzalez et al[41], 2007 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Miklowitz et al[42], 2003 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Petzold et al[45], 2019 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Pakpour et al[43], 2017 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Morris et al[7], 2016 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Kessing et al[44], 2014 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Gumus et al[47], 2015 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Eker et al[48], 2012 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Perry et al[49], 1999 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

The DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for BD were applied in twenty-nine studies[6,8,11,12,15,16,18-21,23-26,29-35,37,40,42,43,46,47]. The DSM-III was applied in four studies[13,27,39,44], and the ICD-10 criteria were applied in two studies[22,41]. One study did not state its diagnostic criteria for BD diagnosis[17].

A total of 2721 patients with BD and 1107 controls were included. Patients were classified as having type I or II BD in twenty-four studies[6,8,11,17-20,23-27,29-32,34,35,37,38,40,42,46,47]. Six studies evaluated BD type I patients[21,28,33,39,41,45], and only one study assessed BD type II patients[15].

Psychoeducation programs in patients with BD: Psychoeducation interventions and outcomes are summarized in Table 2. Eleven studies[11,15-24] assessed the psychoeducation manual for BD (PMBD)[6]. Patients in the PMBP group presented a lower incidence of new mood episodes, fewer hospitalizations[11,23,24], and reduced LOS[11,21,24]. Patients in the PMBD group had a reduction in the number of depressive episodes[17,18,23]. No difference was observed in the number of mood episodes in four studies[15,16,18,21]. PMBD was associated with a higher adherence to pharmacological treatment and a higher quality of life in one study[20]. PMDB did not result in better functional parameters[19,21].

Table 2.

Extracted data from studies that evaluated psychoeducation in patients with bipolar disorder

|

Ref.

|

BD

|

Sample size, N (P × C)

|

Age in years (P × C)

|

Female frequency (%) (P × C)

|

Intervention

|

Applied scales/parameters

|

Results

|

| Zhang et al[14], 2019 | I e II | 35 × 39 | 34.2 × 34.6 | 57.1 × 46.2 | SCIT | YMRS | P = 0.21 |

| HDRS | P = 0.11 | ||||||

| FAST | P < 0.001 | ||||||

| TMTA | P = 0.77 | ||||||

| SDMT | P = 0.09 | ||||||

| HVLT-R | P = 0.09 | ||||||

| SCWT | P = 0.054 | ||||||

| Wiener et al[15], 2017 | ND | 32 × 29 | 24 × 23.81 | 83.3 × 76.2 | PMBD | HDRS | P = 0.028 |

| YMRS | P = 0.879 | ||||||

| Cardoso et al[16], 2015 | ND | 32 × 29 | 24.09 × 24.03 | 65.6 × 72.4 | PMBD | BRIAN | P = 0.88 |

| HARS | P = 0.175 | ||||||

| YMRS | P = 0.576 | ||||||

| HDRS | P = 0.074 | ||||||

| Cardodo et al[17], 2014 | ND | 32 × 29 | 24.09 × 24.03 | 65.6 × 72.4 | PMBD | HDRS | P = 0.001 |

| YMRS | P = 0.102 | ||||||

| Faria et al[18], 2014 | II | 32 × 29 | 24.09 × 24.03 | 72.4 × 65.6 | PMBD | BRIAN | P = 0.01 |

| Depressive symptoms | P = 0.001 | ||||||

| Kurdal et al[19], 2014 | ND | 40 × 40 | 37.17 × 33.9 | 35 × 40 | PMBD | BDFQ | P > 0.005 |

| Javadpour et al[20], 2013 | I e II | 45 × 41 | 24.4/23.2 | 23 × 21 | PMBD | WHOQOL-BREF | P < 0.001 |

| MARS | P = 0.008 | ||||||

| Hospitalizations | P < 0.001 | ||||||

| de Barros Pellegrinelli et al[21], 2013 | I e II | 32 × 23 | 43.43 × 43.74 | 23 × 15 | PMBD | HDRS | P = 0.820 |

| YMRS | P = 0.716 | ||||||

| SAS | P = 0.114 | ||||||

| GAF | P = 0.586 | ||||||

| CGI | P = 0.026 | ||||||

| Candini et al[22], 2013 | I e II | 57 × 45 | 41.5 × 44.8 | 52.6 × 48.9 | PMBD | Hospitalizations | P = 0.001 |

| Number of days of hospitalization | P = 0.001 | ||||||

| Colom et al[11], 2009 | I e II | 60 × 60 | 34.03 × 34.26 | 63.3 × 63.3 | PMBD | New mood episode | P = 0.002 |

| Hospitalizations | P = 0.023 | ||||||

| Number of days of hospitalization | P = 0.047 | ||||||

| Colom et al[23], 2003 | I | 25 × 25 | 35.36 × 34.48 | 64 × 60 | PMBD | Mood episodes in the treatment phase | P = 0.003 |

| Mood episodes after 2 yr | P = 0.008 | ||||||

| Depressive episodes | P = 0.004 | ||||||

| Hospitalizations | P = 0.001 | ||||||

| Colom et al[24], 2003 | I e II | 60 × 60 | 23.25 × 22.26 | 63.3 × 63.3 | PMBD | New mood episode | P = 0.001 |

| Hospitalizations | P = 0.05 | ||||||

| Number of days of hospitalization | P = 0.05 | ||||||

| Dalum et al[25], 2018 | ND | 23 × 24 | 41 × 45 | 46 × 44 | IMR | IMRS-P | P = 0.14 |

| IMRS-S | P = 0.76 | ||||||

| Depp et al[26], 2015 | I e II | 51 × 63 | 46.9 × 48.1 | 53.7 × 63.4 | PRISM | YMRS | P = 0.004 |

| MADRS | P = 0.036 | ||||||

| IIS | P = 0.636 | ||||||

| Lauder et al[27], 2015 | I e II | 71 × 59 | 39.87 × 41.35 | 73 × 76 | MS–PLUS | ASRMS | P = 0.02 |

| MADRS | P = 0.003 | ||||||

| MOS-SSS | P = 0.003 | ||||||

| MARS | P = 0.001 | ||||||

| GPF | P = 0.003 | ||||||

| Torrent et al[28], 2013 | I e II | 159 × 80 | 40.59 × 40.47 | 57.1 × 57.5 | FR | FAST | P = 0.002 |

| HDRS | P > 0.05 | ||||||

| YMRS | P > 0.05 | ||||||

| Hospitalizations | P > 0.05 | ||||||

| Smith et al[29], 2011 | I e II | 24 × 26 | 42.7 × 44.7 | 54.2 × 69.2 | BBO | FAST | P = 0.15 |

| GAF | P = 0.21 | ||||||

| SAI | P = 0.44 | ||||||

| WHOQOL-BREF | P = 0.25 | ||||||

| Sylvia et al[30], 2011 | I e II | 4 × 6 | 60 × 50.2 | 75 × 33 | NEW TX | MADRS | P = 0.10 |

| LIFE-RIFT | P = 0.014 | ||||||

| D'Souza et al[31], 2010 | I | 27 × 31 | 40.7 × 39.5 | 51.85 × 51.61 | SIMSEP-BD | ARS | P = 0.001 |

| New mood episode | P = 0.015 | ||||||

| Time between mood episodes | P = 0.001 | ||||||

| Castle et al[32], 2010 | I e II | 42 × 42 | 41.6 × 42.6 | 79 × 26 | MAPS | Mood episode | P = 0.003 |

| Depressive symptoms | P = 0.003 | ||||||

| Knowledge about illness | P > 0.05 | ||||||

| ESM-PA | P = 0.024 | ||||||

| ESM-NA | P = 0.001 | ||||||

| So et et al[46], 2021 | I e II | 38 × 26 | 35.8 × 43.1 | 78.9 × 73.1 | LGP | Medication adherence | P > 0.05 |

| Sajatovic et al[33], 2009 | I e II | 80 × 80 | 41.13 × 40 | 73.75 × 87.5 | LGP | DAI | P = 0.366 |

| SRTAB | P = 0.577 | ||||||

| GAS | P = 0.382 | ||||||

| Miklowitz et al[34], 2007 | I e II | 163 × 130 | 40.1 × 40 | ND | IPI | Remission of symptoms 1 yr | P = 0.001 |

| Miklowitz et al[35], 2007 | I e II | 84 × 68 | ND | 59 × 59 | IPI | LIFE-RIFT | P = 0.006 |

| González Isasi et al[36], 2014 | I | 20 × 20 | 43.35 × 39.25 | 45 × 50 | CBT | STAI-S | P = 0.062 |

| YMRS | P = 0.009 | ||||||

| BDI | P = 0.131 | ||||||

| IS | P = 0.001 | ||||||

| Parikh et al[37], 2012 | I e II | 109 × 95 | 40.9 × 40.9 | 53.2 × 63.2 | CBT | LIFE | P > 0.05 |

| CARS-M | P = 0.089 | ||||||

| HDRS | P = 0.089 | ||||||

| Zaretsky et al[38], 2008 | I e II | 40 × 39 | ND | ND | CBT | CARS-M | P = 0.001 |

| HDRS | P = 0.001 | ||||||

| Proudfoot et al[39], 2012 | ND | 139 × 134 | 35.3 × 40.9 | 66.9 × 69.4 | BEP | GADS | P > 0.05 |

| WSAS | P > 0.05 | ||||||

| SWLS | P > 0.05 | ||||||

| BRIEF IPQ | P = 0.001 | ||||||

| Aubry et al[40], 2012 | I e II | 50 × 35 | 46 × 52 | 66 × 62.9 | LGP | Hospitalizations | P = 0.001 |

| Number of hospitalizations | P = 0.009 | ||||||

| Gonzalez et al[41], 2007 | I e II | 11 × 11 | 40.5 × 41.0 | 45.45 × 45.45 | IOM | GAF | P = 0.65 |

| CGI-BD | P = 0.06 | ||||||

| Depressive symptoms | P = 0.005 | ||||||

| Miklowitz et al[42], 2003 | I | 31 × 70 | 35.6 × 36.6 | 58 × 66 | FFT | SADS-C | P = 0.001 |

| New mood episode | P = 0.001 | ||||||

| MTS | P = 0.001 | ||||||

| Pakpour et al[43], 2017 | I e II | 134 × 136 | 41.8 × 41.2 | 55.2 × 50.7 | GP | MARS | P = 0.001 |

| YMRS | P = 0.001 | ||||||

| CGI | P = 0.001 | ||||||

| QoL.BD | P = 0.001 | ||||||

| Petzold et al[45], 2019 | I e II | 39 × 34 | 44.32 × 42.69 | 43.6 × 47.1 | GP | New mood episode | P = 0.175 |

| YMRS | P = 0.241 | ||||||

| HDRS | P = 0.58 | ||||||

| SF-36 | P = 0.359 | ||||||

| Morriss et al[7], 2016 | I e II | 153 × 151 | 44.2 × 46·5 | 60 × 56 | GP | Time between mood episodes | P = 0.012 |

| SOFAS | P > 0.05 | ||||||

| SAS | P > 0.05 | ||||||

| Kessing et al[44], 2014 | I | 72 × 86 | 64.1 × 63 | 61.1 × 48.8 | GP | Time between mood episodes | P = 0.014 |

| Hospitalizations | P = 0.064 | ||||||

| Gumus et al[47], 2015 | I e II | 41 × 41 | 38.7 × 40.05 | 40.5 × 56.1 | GP | Number of mood episodes | P = 0.208 |

| Eker et al[48], 2012 | ND | 35 × 36 | 34.57 × 36.54 | 54.3 × 52.8 | GP | ANT | P < 0.005 |

| MARS | P < 0.005 | ||||||

| Perry et al[49], 1999 | I | 34 × 35 | 44.1 × 45 | 68 × 69 | GP | Time between manic episodes | P = 0.008 |

| Time between depressive episodes | P = 0.19 |

ANT: Attitudes towards neuroleptic treatment; ASRMS: Altman self-rating mania scale; ARS: Medication adherence scale; B: Baseline; BBO: Beating bipolar online; BD: Bipolar disorder; BDG: Bipolar disorder group; BDI: Beck depression inventory; BDFQ: Bipolar Disorder Functioning Questionnaire; BEP: Bipolar Education Program; BDNF: Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor; BRIAN: Biological Rhythm Interview of Assessment in Neuropsychiatry; BRIEF IPQ: The Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire; C: Controls; CARS-M: Clinician-Administered Rating Scale for Mania; CBT: Cognitive-behavioral therapy; CC: Collaborative care; CGI-BD: Clinical Global Impression Scale for Bipolar Disorder; DAI: Drug Attitude Inventory; EDM: Education about Disorders and Medications; ESM-PA: With in person positive affect as measured by using Experience Sampling Method; ESM-NA: Within-person negative affect as measured by using Experience Sampling Method; FAST: Functional Assessment Test; FFT: Family-focused treatment; FR: Functional remediation; GADS: The Goldberg Anxiety and Depression Scale; GAF: Global Assessment of Functioning; GAS: Global Assessment Scale; HVLT-R: Hopkins Verbal Learning Tests-Revised; GDNF: Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor; GPF: Global Measure of Psychosocial Functioning; GP: Group Psychoeducation; HARS: Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale; HDRS: Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; IOM: Integrative Outpatient Model; IMR: Illness Management and Recovery program; IMRS–P: Illness Management and Recovery Scale–participants’ version; IMRS–S: Illness Management and Recovery Scale–staffs; IPI: Intensive Psychosocial Intervention; IS: Maladjustment scale; IRSRT: Interpersonal and social rhythm therapy; LGP: Life Goals Program; LIFE: Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation; LIFE-RIFT: The Range of Impaired Functioning Tool; MADRS: Montgomery–Asberg Depression Rating Scale; MOSSF-36: Medical Outcomes Survey Short-form General Health Survey; MTS: Maintenance Treatment Scale; MARS: Medication Adherence Rating Scale; MAPS: Monitoring mood and activities (M), assessing prodromes (A), preventing relapse (P) and setting Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic, Time-framed (SMART) goals (S); MARS: Medication adherence rating scale; MS-PLUS: MoodSwings-Plus; MOS-SSS: Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey; ND: Not described; NEW TX-Program: Nutrition/weight loss, Exercise, and Wellness Treatment; NGF: Nerve growth factor; P: Patients; PMBD: Psychoeducation Manual For Bipolar Disorder; PRISM: Personalized Real-Time Intervention for Stabilizing Mood , QoL.BD: Quality of Life in Bipolar Disorder scale; SAI: Schedule for Assessment of Insight; SADS-C: Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia, Change Version; SAS: Social Adjustment Scale; SCIT: Social cognition and Interaction Training; SCWT: Stroop Color-Word Test; SDMT: Symbol Digit Modalities Test; SIMSEP-BD: Systematic Illness Management Skills Enhancement Program Bipolar Disorder; SF-36: 36-Item Short Form Survey; SOFAS: Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale; SRTAB: Self-reported treatment adherence behaviours; STAI-S: State Trait Anxiety Inventory; SWLS: The Satisfaction with Life Scale; TMTA: Trail Making Test-A; WHOQOL–BREF: World Health Organization Quality of Life, Brief version; WSAS: The Work and Social Adjustment Scale; YMRS: Young Mania Rating Scale.

Eight studies evaluated Group psychoeducation (GP)[45-51]. BD included in the GP compared to controls exhibited a longer interval between mood episodes[44], higher adherence to pharmacological treatment[45,46], and lower rates of hospital admissions[44]. GP interventions were not associated with functional, social or family improvements[46].

Intensive psychosocial intervention was not associated with functional state improvement[35], mood episode frequency[33], or new mood episodes (Hamilton depression rating scale). One study showed a reduction in the number of hospitalizations and mean hospitalization time[37].

Other psychoeducational techniques were applied in eleven studies[11,22-24,26-29,36,38,39]. Illness Management and Recovery program (IMR)[22]; Family-focused treatment (FFT)[42]; Systematic Illness Management Skills Enhancement Programme BD (SIMSEP-BD)[31] and MoodSwings-Plus (MS-PLUS)[27] were associated with increased adherence to pharmacological treatment. Nutrition/weight loss, exercise, and wellness treatment (NEW Tx)[30] and Personalized Real-Time Intervention for Stabilizing Mood (PRISM)[25] were associated with a reduction in severity of mania symptoms. Depressive symptoms were less severe in patients submitted to MAPS-monitoring mood and activities (M), assessing prodromes (A), preventing relapse (P) and setting Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic, Time-framed (SMART) goals (S)[32], integrative outpatient model (IOM)[38], and PRISM[25] interventions, when compared to control intervention. The online bipolar education program (BEP) was associated with a reduction in anxiety symptoms[39]. There was a reduction in the frequency of mood episodes in patients submitted to IMR[26] and MAPS[33]. Functional remediation (FR) was associated with improvement in functional status[28]. Social cognition and interaction training (SCIT)[14], FR[28], FFT[41], SIMSEP-BD[31], MAPS[32] and MS-PLUS[27] were not associated with changes in the severity of mood symptoms. FR did not influence the number of hospital admissions[28]. BEP[39], Beating bipolar online[29], and IOM[41] did not influence functional status. BEP was not associated with improvement in the quality of life or increased insight[29].

Studies with relatives of patients with BD: Nine clinical studies were included. Nine studies scored five or more stars[50-58] according to the NOS scale[13] (Table 3). There were seven randomized[50-52,54,58] and two nonrandomized studies[53,57]. Two studies evaluated euthymic patients[51,53]. Information regarding mood episodes was not available in seven studies[50-52,55-58].

Table 3.

Newcastle–Ottawa scale evaluation for studies that evaluated psychoeducation in relatives of patients with bipolar disorder

|

Ref.

|

Representativeness of the exposed cohort

|

Selection of the non-exposed cohort

|

Ascertainment of exposure

|

Demonstration that outcome of interest was not present at start of study

|

Comparability of cohorts on the basis of the design or analysis

|

Assessment of outcome

|

Follow-up long enough for outcomes to occur

|

Adequacy of follow up of cohorts

|

Total

|

| Hubbard et al[50], 2016 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 7 |

| Fiorillo et al[51], 2015 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| Madigan et al[52], 2012 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Reinares et al[53], 2008 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Solomon et al[54], 2008 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 6 |

| Reinares et al[55], 2004 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| Van Gent et al[56], 1991 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 6 |

| Miklowitz et al[57], 2000 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Simoneau et al[58], 1999 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 6 |

Four studies diagnosed patients according to the DSM-III criteria[49,51-53], and four studies applied the DSM-IV[46-48,50]. One study did not state the BD diagnostic criteria[50]. Two studies assessed BD type I and BD type II patients[48,50]; three studies included exclusively BD type I patients[46,49,52]. Four studies did not specify the BD type[45,47,51,53].

One hundred thirteen relatives were included in psychoeducation programs: one hundred and six were couples; twelve were sons/daughters; and ten were brothers/ sisters. Fifty-four parents were included in the control groups, eighty-nine were couples, two were sons/daughters, six were brothers/sisters, and two were friends.

Psychoeducation programs aimed at family members of patients with BD: Psychoeducation interventions and outcomes are summarized in Table 4. Two studies[52,53] compared the program of pharmacotherapy and FFT and Crisis management with naturalistic follow-up (CMNF). There was no difference in the severity of mood symptoms after a one-year follow-up[52]. There was a reduction in the frequency of mood episodes in the FFT compared to the CMNF[52].

Table 4.

Extracted data from studies that evaluated psychoeducation in relatives of patients with bipolar disorder

|

Ref.

|

BD

|

Psychoeducation group

|

Group control

|

Applied scales/parameters

|

Results

|

||||

|

Psychoeducation strategy

|

n

(%)

|

|

Intervention strategy

|

n

(%)

|

|

||||

| Hubbard et al[50], 2016 | ND | GCPBD | 18 | 8 Partner; 10 Parents | WL | 14 | 3 Partner; 8 Parents; 1 Sibling; 2 Friend | DASS- 21 | P = 0.52 |

| BAS | P = 0.91 | ||||||||

| KBDS | P > 0.05 | ||||||||

| BDSS | P > 0.05 | ||||||||

| Fiorillo et al[51], 2015 | BD I | PFI | 85 | 21 Parents; 44 Partner; 10 Son; 9 Sibling; 1 Other | WI | 70 | 23 Parents; 31 Partner; 11 Son; 3 Sibling; 2 Other | Subjective burden | P = 0.001 |

| Professional help | P = 0.001 | ||||||||

| Help in emergencies | P = 0.01 | ||||||||

| Madigan et al[52], 2012 | ND | MFGP; SFGP | 18; 19 | ND | WI | 10 | ND | Caregiver knowledge | P = 0.404 |

| IEQ | P = 0.795 | ||||||||

| GHQ12 | P = 0.723 | ||||||||

| WHOQOL Bref | P = 0.355 | ||||||||

| GAF | P = 0.617 | ||||||||

| Reinares et al[53], 2008 | BD I e II | PFI | 57 | 35 Parents; 20 Partner; 2 Offspring/siblings | WI | 56 | 27 Parents; 25 Partner; 4 Offspring/siblings | Amount of daily contact between the patient and the caregiver | P = 0.757 |

| Manic/hypomanic recurrence time | P = 0.015 | ||||||||

| Medication adherence | P = 0.611 | ||||||||

| Solomon et al[54], 2008 | BD I | MFGP; IFT | 21; 16 | ND | WI | 16 | ND | New mood episode | P = 0.47 |

| Hospitalization frequency | P = 0.04 | ||||||||

| BRMS | P = 0.44 | ||||||||

| HAM-D | P = 0.12 | ||||||||

| Reinares et al[55], 2004 | BD I e II | PFI | 30 | 17 Parents; 12 Partner; 1 Sibiling | WI | 15 | 6 Parents; 6 Partner; 2 Son; 1 Sibiling | HAM–D | P > 0.05 |

| YMRS | P > 0.05 | ||||||||

| Subjective burden of the caregiver | P = 0.48 | ||||||||

| FES | P = 0.22 | ||||||||

| Knowledge about the disorder | P = 0.001 | ||||||||

| Van Gent et al[56], 1991 | ND | GT | 14 | 14 Partner | WI | 12 | 12 Partner | IPSQ | P > 0.05 |

| IPP | P > 0.05 | ||||||||

| SCL-90 | P > 0.05 | ||||||||

| Miklowitz et al[57], 2000 | BD I | FFT | 31 | ND | CMNF | 70 | ND | New mood episode | P = 0.042 |

| Depressive symptoms | P = 0.06 | ||||||||

| Manic symptoms | P = 0.59 | ||||||||

| Simoneau et al[58], 1999 | ND | FFT | 22 | ND | CMNF | 22 | ND | KPI | P > 0.05 |

BAS: Burden assessment scale; BD: Bipolar disorder; BDSS: Bipolar disorder self-efficacy scale; BPRS: Brief psychiatric rating scale; BRMS: Bech-Rafaelsen Mania Scale; C: Control; CMNF: Crisis management with naturalistic follow-up; DAS: Disability assessment scale; DASS-21: Depression, Anxiety, Stress Scale; FES: Family Environment Scale (Cohesion, Expressiveness e Conflict)-Relationship subscales; FFT: Program of pharmacotherapy and family-focused psychoeducational treatment; GAF: Global Assessment of Functioning; GHQ12: General Health Questionnaire 12; GCPBD: Guide for Caregivers of People with Bipolar Disorder; HAM–D: Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression–17-item; IEQ: Involvement evaluation questionnaire; IFT: Individual family therapy; IPP: Inventory of psychosocial problems; IPSQ: Interactional Problem Solving Questionnaire; KBDS: Knowledge of Bipolar Disorder Scale; KPI: Interactional coding system-assessed verbal and nonverbal communication behaviors of patients and their family; MFGP: Multifamily Group Psychoeducation; N: Total number l; ND: Not described; P: Psychoeducation; PFI: Psychoeducational family intervention; SADS-C: Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia-Change Version; SCL-90: Symptom Checklist; SFGP: Solution Focused Group Psychotherapy; GT: Group therapy; WHOQOL Brief: World Health Organization Quality of Life, Brief version; WI: Without intervention; WL: Waiting list; YMRS: Young Mania Rating Scale.

Three studies assessed the psychoeducational family intervention (PFI) strategy compared to a nonintervention control group[51,53,54]. There were no improvements in the frequency of mood episodes[50], adherence to treatment[53], or caregiver burden[55]. The group submitted to PFI showed a significant improvement in relation to the perception of professional support received and help in times of emergency[51].

Two studies compared multifamily group psychoeducation, individual family therapy (IFT), and solution focused group psychotherapy (SFGP)[52,54]. There were no differences between these strategies regarding reduction in frequency of mood episodes[53,56], quality of life[52], or changes in functional status[53,54]. One study found that parents submitted to IFT reduced the incidence of hospital admissions[54].

The Guide for Caregivers of People with BD[50] was not associated with changes in relatives’ symptoms of anxiety, depression or mania; stress discharge; knowledge of the disease; or changes in the caregiver burden[50].

DISCUSSION

Psychoeducation applied to BD patients and their relatives is associated with a reduction in the frequency of new mood episodes and a reduction in the number of hospital admissions and LOS. Psychoeducational interventions applied to patients contribute to improvement in pharmacological treatment adherence. Psychoeducation does not seem to influence the severity of depressive or manic symptoms or functionality. PMBD was associated with a higher adherence to pharmacological treatment and a higher quality of life in one study[23]. Psychoeducation strategies applied to relatives had no effect on adherence to pharmacological treatment.

Psychoeducational strategies in patients with BD are associated with a lower frequency of mood swings. These results are in line with a previous meta-analysis that evaluated 650 patients; 45% did not present a new mood episode compared to 30% of controls[54]. A possible explanation for this association is that the occurrence of subsyndromal symptoms is one of the main risk factors for new episodes[57,58]. Psychoeducational strategies in patients promote increased understanding about their own disease[59], improve the abilities of recognizing mood subsyndromal symptoms, enable early interventions, and might contribute to refraining new mood episodes[60]. Psychoeducational strategies also provide information about healthier lifestyles, sleep routines, exercise and stress management tips. All these steps are important to the maintenance of the euthymic state in BD[59].

Psychoeducation interventions were effective in reducing the frequency of hospitalizations and LOS and enhanced adherence to pharmacological treatment. Knowledge regarding their own illness might enrich comprehension of the importance of medication use and its effects on mood[61]. Moreover, a higher adherence to treatment is associated with monotherapy and reduced drug side effects[4,62]. Psychoeducational approaches to family members had no influence on treatment adherence.

When applied to patients and family members, psychoeducational approaches did not have an effect on mood severity symptoms, functionality or the quality of life of BD patients. Mood changes might lead to social, interpersonal and occupational impairments and contribute negatively to quality of life[63,64]. Depressive episodes are the most common and the most persistent affective states in BD and are the main cause of functional disability[4]. Residual and persistent depressive symptoms, cognitive decline, sleep deprivation, past history of psychotic symptoms[65,66], current presence of psychiatric comorbidities, use of psychoactive substances[65-68], long course of the disease, number of mood episodes[69-71], and hospitalizations[72] are associated with a reduction in functionality[73].

Family member psychoeducation is related to a lower frequency of mood swings and to a reduction in LOS. As family members acquire knowledge of the disease, they become more able to help patients identify early mood changes, apply assertive strategies to deal with daily situations and crisis management[48,74]. Through the provision of care, acceptance of the disease and dialogue, family members present themselves to the patient as a source of aid and support for decisions about their treatment[75-77].

In regard to the limitations of the present study, we might consider meta-analysis to be unable to be performed, owing to the methodological differences between heterogeneous studies (sample size, duration of follow-up, main results, type of comparison group), the population characteristics (severity, comorbidity, clinical status of patients in recruiting phase) and the intervention itself (target population, format, content, duration). All of these factors hamper the generalization of the results. In addition, the findings of the present study reveal that the characteristics of the sampling must be carefully considered. Patients with severe chronic disease may have poorer treatment responses. Future research to clarify the effectiveness of psychoeducation and to identify the determinants of response to treatment might be required for this population.

CONCLUSION

The data from this systematic review show the positive effects of the psychoeducational intervention on both patients and family members. Despite the lack of effectiveness in some parameters, psychoeducation has been associated with other treatments as an additional intervention. It is recommended that additional studies should approach strategies that aim to maximize the benefits of those therapies, adding interventions focused on family and interpersonal relationships.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

The bipolar disorder (BD) treatment is challenging, and there is some evidence that non-pharmacological interventions promote effects in the treatment of acute mood episodes and maintenance treatment. Psychoeducation is an intervention strategy based on providing patients and/or relatives with information about the disorder to enhance their understanding and enable early identification of warning signs and mood changes, improving treatment adherence, and have showed some results in order to help the BD treatments.

Research motivation

Even using adequate drug strategies, BD is characterized by high rates of occurrence of mood episodes, number of hospital admissions, and a progressive impairment. We aimed to summarize the best evidence of psychoeducation in the treatment of BD, considering patients and their family members.

Research objectives

This systematic review aims to investigate the role of psychoeducation in BD in patients and in their family members.

Research methods

A systematic search of original studies on psychoeducation with patients with Bipolar Affective Disorder and their families was carried out using Medline, Scopus and Lilacs databases. A data extraction table was created based on the Cochrane model and the methodological quality of the studies was assessed according to the criteria of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale.

Research results

Psychoeducation applied to BD patients and their relatives is associated with a reduction in the frequency of new mood episodes and a reduction in the number of hospital admissions and length of stay. Psychoeducational interventions applied to patients contribute to improvement in pharmacological treatment adherence, although the same effect it is not observed when applied to relatives. Psychoeducation does not seem to influence the severity of depressive or manic symptoms or functionality.

Research conclusions

Psychoeducation as an adjunct strategy to pharmacotherapy has been shown to be effective in the treatment of Bipolar Affective Disorder.

Research perspectives

To systematize the effectiveness of psychoeducation intervention on BD patients and family members.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: There is no conflict of interest.

PRISMA 2009 Checklist statement: The authors have read the PRISMA 2009 Checklist, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the PRISMA 2009 Checklist.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Peer-review started: March 3, 2021

First decision: June 5, 2021

Article in press: November 13, 2021

Specialty type: Psychiatry

Country/Territory of origin: Brazil

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Gazdag G, Li XM S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: A P-Editor: Fan JR

Contributor Information

Juliana Lemos Rabelo, Interdisciplinary Laboratory of Medical Investigation–School of Medicine, UFMG, Belo Horizonte 30130-100, Minas Gerais, Brazil; Programa de Extensão em Psiquiatria e Psicologia de Idosos, UFMG, Belo Horizonte 30130-100, Minas Gerais, Brazil.

Breno Fiuza Cruz, Interdisciplinary Laboratory of Medical Investigation–School of Medicine, UFMG, Belo Horizonte 30130-100, Minas Gerais, Brazil; Programa de Extensão em Psiquiatria e Psicologia de Idosos, UFMG, Belo Horizonte 30130-100, Minas Gerais, Brazil; Department of Mental Health, School of Medicine, UFMG, Belo Horizonte 30130-100, Minas Gerais, Brazil.

Jéssica Diniz Rodrigues Ferreira, Programa de Extensão em Psiquiatria e Psicologia de Idosos, UFMG, Belo Horizonte 30130-100, Minas Gerais, Brazil.

Bernardo de Mattos Viana, Programa de Extensão em Psiquiatria e Psicologia de Idosos, UFMG, Belo Horizonte 30130-100, Minas Gerais, Brazil; Department of Mental Health, School of Medicine, UFMG, Belo Horizonte 30130-100, Minas Gerais, Brazil.

Izabela Guimarães Barbosa, Interdisciplinary Laboratory of Medical Investigation–School of Medicine, UFMG, Belo Horizonte 30130-100, Minas Gerais, Brazil; Programa de Extensão em Psiquiatria e Psicologia de Idosos, UFMG, Belo Horizonte 30130-100, Minas Gerais, Brazil; Department of Mental Health, School of Medicine, UFMG, Belo Horizonte 30130-100, Minas Gerais, Brazil. izabelagb@gmail.com.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association (APA) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vigo D, Thornicroft G, Atun R. Estimating the true global burden of mental illness. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3:171–178. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00505-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vieta E, Berk M, Schulze TG, Carvalho AF, Suppes T, Calabrese JR, Gao K, Miskowiak KW, Grande I. Bipolar disorders. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:18008. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2018.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bosaipo NB, Borges VF Juruena MF. Bipolar disorder: a review of conceptual and clinical aspects. Medicina. Ribeirao Preto Online. 2017;50:72–74. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Demissie M, Hanlon C, Birhane R, Ng L, Medhin G, Fekadu A. Psychological interventions for bipolar disorder in low- and middle-income countries: systematic review. BJPsych Open. 2018;4:375–384. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2018.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colom F, Vieta E, Scott J. Psychoeducation Manual for Bipolar Disorder. Cambridge University Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morriss R, Lobban F, Riste L, Davies L, Holland F, Long R, Lykomitrou G, Peters S, Roberts C, Robinson H, Jones S NIHR PARADES Psychoeducation Study Group. Clinical effectiveness and acceptability of structured group psychoeducation versus optimised unstructured peer support for patients with remitted bipolar disorder (PARADES): a pragmatic, multicentre, observer-blind, randomised controlled superiority trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3:1029–1038. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30302-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Novick DM, Swartz HA. Evidence-Based Psychotherapies for Bipolar Disorder. Focus (Am Psychiatr Publ) 2019;17:238–248. doi: 10.1176/appi.focus.20190004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miklowitz DJ, Efthimiou O, Furukawa TA, Scott J, McLaren R, Geddes JR, Cipriani A. Adjunctive Psychotherapy for Bipolar Disorder: A Systematic Review and Component Network Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78:141–150. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.2993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chatterton ML, Stockings E, Berk M, Barendregt JJ, Carter R, Mihalopoulos C. Psychosocial therapies for the adjunctive treatment of bipolar disorder in adults: network meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2017;210:333–341. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.116.195321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colom F, Vieta E, Sánchez-Moreno J, Palomino-Otiniano R, Reinares M, Goikolea JM, Benabarre A, Martínez-Arán A. Group psychoeducation for stabilised bipolar disorders: 5-year outcome of a randomised clinical trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;194:260–265. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.040485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Higgins J, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page M, Welch V. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 2nd Edition. Chichester (UK): John Wiley & Sons, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analysis, 2019. [cited 10 January 2021]. Available from: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp .

- 14.Zhang Y, Ma X, Liang S, Yu W, He Q, Zhang J, Bian Y. Social cognition and interaction training (SCIT) for partially remitted patients with bipolar disorder in China. Psychiatry Res. 2019;274:377–382. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wiener CD, Molina ML, Moreira FP, Dos Passos MB, Jansen K, da Silva RA, de Mattos Souza LD, Oses JP. Brief psychoeducation for bipolar disorder: Evaluation of trophic factors serum levels in young adults. Psychiatry Res. 2017;257:367–371. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.07.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cardoso Tde A, Campos Mondin T, Reyes AN, Zeni CP, Souza LD, da Silva RA, Jansen K. Biological Rhythm and Bipolar Disorder: Twelve-Month Follow-Up of a Randomized Clinical Trial. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2015;203:792–797. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cardoso Tde A, Farias Cde A, Mondin TC, da Silva Gdel G, Souza LD, da Silva RA, Pinheiro KT, do Amaral RG, Jansen K. Brief psychoeducation for bipolar disorder: impact on quality of life in young adults in a 6-month follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Psychiatry Res. 2014;220:896–902. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Faria AD, de Mattos Souza LD, de Azevedo Cardoso T, Pinheiro KA, Pinheiro RT, da Silva RA, Jansen K. The influence of psychoeducation on regulating biological rhythm in a sample of patients with bipolar II disorder: a randomized clinical trial. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2014;7:167–174. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S52352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kurdal E, Tanriverdi D, Savas HA. The effect of psychoeducation on the functioning level of patients with bipolar disorder. West J Nurs Res. 2014;36:312–328. doi: 10.1177/0193945913504038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Javadpour A, Hedayati A, Dehbozorgi GR, Azizi A. The impact of a simple individual psycho-education program on quality of life, rate of relapse and medication adherence in bipolar disorder patients. Asian J Psychiatr. 2013;6:208–213. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Barros Pellegrinelli K, de O Costa LF, Silval KI, Dias VV, Roso MC, Bandeira M, Colom F, Moreno RA. Efficacy of psychoeducation on symptomatic and functional recovery in bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2013;127:153–158. doi: 10.1111/acps.12007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Candini V, Buizza C, Ferrari C, Caldera MT, Ermentini R, Ghilardi A, Nobili G, Pioli R, Sabaudo M, Sacchetti E, Saviotti FM, Seggioli G, Zanini A, de Girolamo G. Is structured group psychoeducation for bipolar patients effective in ordinary mental health services? J Affect Disord. 2013;151:149–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.05.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Colom F, Vieta E, Reinares M, Martínez-Arán A, Torrent C, Goikolea JM, Gastó C. Psychoeducation efficacy in bipolar disorders: beyond compliance enhancement. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:1101–1105. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n0917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Colom F, Vieta E, Martinez-Aran A, Reinares M, Goikolea JM, Benabarre A, Torrent C, Comes M, Corbella B, Parramon G, Corominas J. A randomized trial on the efficacy of group psychoeducation in the prophylaxis of recurrences in bipolar patients whose disease is in remission. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:402–407. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.4.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dalum HS, Waldemar AK, Korsbek L, Hjorthøj C, Mikkelsen JH, Thomsen K, Kistrup K, Olander M, Lindschou J, Nordentoft M, Eplov LF. Participants' and staffs' evaluation of the Illness Management and Recovery program: a randomized clinical trial. J Ment Health. 2018;27:30–37. doi: 10.1080/09638237.2016.1244716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Depp CA, Ceglowski J, Wang VC, Yaghouti F, Mausbach BT, Thompson WK, Granholm EL. Augmenting psychoeducation with a mobile intervention for bipolar disorder: a randomized controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 2015;174:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.10.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lauder S, Chester A, Castle D, Dodd S, Gliddon E, Berk L, Chamberlain J, Klein B, Gilbert M, Austin DW, Berk M. A randomized head to head trial of MoodSwings.net.au: an Internet based self-help program for bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2015;171:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Torrent C, Bonnin Cdel M, Martínez-Arán A, Valle J, Amann BL, González-Pinto A, Crespo JM, Ibáñez Á, Garcia-Portilla MP, Tabarés-Seisdedos R, Arango C, Colom F, Solé B, Pacchiarotti I, Rosa AR, Ayuso-Mateos JL, Anaya C, Fernández P, Landín-Romero R, Alonso-Lana S, Ortiz-Gil J, Segura B, Barbeito S, Vega P, Fernández M, Ugarte A, Subirà M, Cerrillo E, Custal N, Menchón JM, Saiz-Ruiz J, Rodao JM, Isella S, Alegría A, Al-Halabi S, Bobes J, Galván G, Saiz PA, Balanzá-Martínez V, Selva G, Fuentes-Durá I, Correa P, Mayoral M, Chiclana G, Merchan-Naranjo J, Rapado-Castro M, Salamero M, Vieta E. Efficacy of functional remediation in bipolar disorder: a multicenter randomized controlled study. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170:852–859. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12070971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith DJ, Griffiths E, Poole R, di Florio A, Barnes E, Kelly MJ, Craddock N, Hood K, Simpson S. Beating Bipolar: exploratory trial of a novel Internet-based psychoeducational treatment for bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2011;13:571–577. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2011.00949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sylvia LG, Nierenberg AA, Stange JP, Peckham AD, Deckersbach T. Development of an integrated psychosocial treatment to address the medical burden associated with bipolar disorder. J Psychiatr Pract. 2011;17:224–232. doi: 10.1097/01.pra.0000398419.82362.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.D'Souza R, Piskulic D, Sundram S. A brief dyadic group based psychoeducation program improves relapse rates in recently remitted bipolar disorder: a pilot randomised controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 2010;120:272–276. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Castle D, White C, Chamberlain J, Berk M, Berk L, Lauder S, Murray G, Schweitzer I, Piterman L, Gilbert M. Group-based psychosocial intervention for bipolar disorder: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196:383–388. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.058263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sajatovic M, Davies MA, Ganocy SJ, Bauer MS, Cassidy KA, Hays RW, Safavi R, Blow FC, Calabrese JR. A comparison of the life goals program and treatment as usual for individuals with bipolar disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60:1182–1189. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.60.9.1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miklowitz DJ, Otto MW, Frank E, Reilly-Harrington NA, Kogan JN, Sachs GS, Thase ME, Calabrese JR, Marangell LB, Ostacher MJ, Patel J, Thomas MR, Araga M, Gonzalez JM, Wisniewski SR. Intensive psychosocial intervention enhances functioning in patients with bipolar depression: results from a 9-month randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:1340–1347. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07020311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miklowitz DJ, Otto MW, Frank E, Reilly-Harrington NA, Wisniewski SR, Kogan JN, Nierenberg AA, Calabrese JR, Marangell LB, Gyulai L, Araga M, Gonzalez JM, Shirley ER, Thase ME, Sachs GS. Psychosocial treatments for bipolar depression: a 1-year randomized trial from the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:419–426. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.4.419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.González Isasi A, Echeburúa E, Limiñana JM, González-Pinto A. Psychoeducation and cognitive-behavioral therapy for patients with refractory bipolar disorder: a 5-year controlled clinical trial. Eur Psychiatry. 2014;29:134–141. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2012.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parikh SV, Zaretsky A, Beaulieu S, Yatham LN, Young LT, Patelis-Siotis I, Macqueen GM, Levitt A, Arenovich T, Cervantes P, Velyvis V, Kennedy SH, Streiner DL. A randomized controlled trial of psychoeducation or cognitive-behavioral therapy in bipolar disorder: a Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety treatments (CANMAT) study [CME] J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73:803–810. doi: 10.4088/JCP.11m07343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zaretsky A, Lancee W, Miller C, Harris A, Parikh SV. Is cognitive-behavioural therapy more effective than psychoeducation in bipolar disorder? Can J Psychiatry. 2008;53:441–448. doi: 10.1177/070674370805300709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Proudfoot J, Parker G, Manicavasagar V, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Whitton A, Nicholas J, Smith M, Burckhardt R. Effects of adjunctive peer support on perceptions of illness control and understanding in an online psychoeducation program for bipolar disorder: a randomised controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 2012;142:98–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aubry JM, Charmillot A, Aillon N, Bourgeois P, Mertel S, Nerfin F, Romailler G, Stauffer MJ, Gex-Fabry M, de Andrés RD. Long-term impact of the life goals group therapy program for bipolar patients. J Affect Disord. 2012;136:889–894. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gonzalez JM, Prihoda TJ. A case study of psychodynamic group psychotherapy for bipolar disorder. Am J Psychother. 2007;61:405–422. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.2007.61.4.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miklowitz DJ, George EL, Richards JA, Simoneau TL, Suddath RL. A randomized study of family-focused psychoeducation and pharmacotherapy in the outpatient management of bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:904–912. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.9.904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pakpour AH, Modabbernia A, Lin CY, Saffari M, Ahmadzad Asl M, Webb TL. Promoting medication adherence among patients with bipolar disorder: a multicenter randomized controlled trial of a multifaceted intervention. Psychol Med. 2017;47:2528–2539. doi: 10.1017/S003329171700109X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kessing LV, Hansen HV, Christensen EM, Dam H, Gluud C, Wetterslev J Early Intervention Affective Disorders (EIA) Trial Group. Do young adults with bipolar disorder benefit from early intervention? J Affect Disord. 2014;152-154:403–408. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Petzold J, Mayer-Pelinski R, Pilhatsch M, Luthe S, Barth T, Bauer M, Severus E. Short group psychoeducation followed by daily electronic self-monitoring in the long-term treatment of bipolar disorders: a multicenter, rater-blind, randomized controlled trial. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2019;7:23. doi: 10.1186/s40345-019-0158-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.So SH, Mak AD, Chan PS, Lo CC, Na S, Leung MH, Ng IH, Chau AKC, Lee S. Efficacy of Phase 1 of Life Goals Programme on symptom reduction and mood stability for bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2021;281:949–957. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gumus F, Buzlu S, Cakir S. Effectiveness of individual psychoeducation on recurrence in bipolar disorder; a controlled study. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2015;29:174–179. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2015.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Eker F, Harkın S. Effectiveness of six-week psychoeducation program on adherence of patients with bipolar affective disorder. J Affect Disord. 2012;138:409–416. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Perry A, Tarrier N, Morriss R, McCarthy E, Limb K. Randomised controlled trial of efficacy of teaching patients with bipolar disorder to identify early symptoms of relapse and obtain treatment. BMJ. 1999;318:149–153. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7177.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hubbard AA, McEvoy PM, Smith L, Kane RT. Brief group psychoeducation for caregivers of individuals with bipolar disorder: A randomized controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 2016;200:31–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fiorillo A, Del Vecchio V, Luciano M, Sampogna G, De Rosa C, Malangone C, Volpe U, Bardicchia F, Ciampini G, Crocamo C, Iapichino S, Lampis D, Moroni A, Orlandi E, Piselli M, Pompili E, Veltro F, Carrà G, Maj M. Efficacy of psychoeducational family intervention for bipolar I disorder: A controlled, multicentric, real-world study. J Affect Disord. 2015;172:291–299. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Madigan K, Egan P, Brennan D, Hill S, Maguire B, Horgan F, Flood C, Kinsella A, O'Callaghan E. A randomised controlled trial of carer-focussed multi-family group psychoeducation in bipolar disorder. Eur Psychiatry. 2012;27:281–284. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Reinares M, Colom F, Sánchez-Moreno J, Torrent C, Martínez-Arán A, Comes M, Goikolea JM, Benabarre A, Salamero M, Vieta E. Impact of caregiver group psychoeducation on the course and outcome of bipolar patients in remission: a randomized controlled trial. Bipolar Disord. 2008;10:511–519. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2008.00588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Solomon DA, Keitner GI, Ryan CE, Kelley J, Miller IW. Preventing recurrence of bipolar I mood episodes and hospitalizations: family psychotherapy plus pharmacotherapy versus pharmacotherapy alone. Bipolar Disord. 2008;10:798–805. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2008.00624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Reinares M, Vieta E, Colom F, Martínez-Arán A, Torrent C, Comes M, Goikolea JM, Benabarre A, Sánchez-Moreno J. Impact of a psychoeducational family intervention on caregivers of stabilized bipolar patients. Psychother Psychosom. 2004;73:312–319. doi: 10.1159/000078848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.van Gent EM, Zwart FM. Psychoeducation of partners of bipolar-manic patients. J Affect Disord. 1991;21:15–18. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(91)90013-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Miklowitz DJ, Simoneau TL, George EL, Richards JA, Kalbag A, Sachs-Ericsson N, Suddath R. Family-focused treatment of bipolar disorder: 1-year effects of a psychoeducational program in conjunction with pharmacotherapy. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48:582–592. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00931-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Simoneau TL, Miklowitz DJ, Richards JA, Saleem R, George EL. Bipolar disorder and family communication: effects of a psychoeducational treatment program. J Abnorm Psychol. 1999;108:588–597. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.108.4.588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Joas E, Bäckman K, Karanti A, Sparding T, Colom F, Pålsson E, Landén M. Psychoeducation for bipolar disorder and risk of recurrence and hospitalization - a within-individual analysis using registry data. Psychol Med. 2020;50:1043–1049. doi: 10.1017/S0033291719001053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Simhandl C, König B, Amann BL. A prospective 4-year naturalistic follow-up of treatment and outcome of 300 bipolar I and II patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75:254–62; quiz 263. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13m08601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Malhi GS, Bell E, Bassett D, Boyce P, Bryant R, Hazell P, Hopwood M, Lyndon B, Mulder R, Porter R, Singh AB, Murray G. The 2020 Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for mood disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2021;55:7–117. doi: 10.1177/0004867420979353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Velentza O, Grampsa E, Basiliadi E. Psychoeducational Interventions in Bipolar Disorder. Am J Nurs Sci . 2018;7:51–56. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vieta E, Salagre E, Grande I, Carvalho AF, Fernandes BS, Berk M, Birmaher B, Tohen M, Suppes T. Early Intervention in Bipolar Disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175:411–426. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.17090972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Forcada I, Mur M, Mora E, Vieta E, Bartrés-Faz D, Portella MJ. The influence of cognitive reserve on psychosocial and neuropsychological functioning in bipolar disorder. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015;25:214–222. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2014.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Anaya C, Torrent C, Caballero FF, Vieta E, Bonnin Cdel M, Ayuso-Mateos JL CIBERSAM Functional Remediation Group. Cognitive reserve in bipolar disorder: relation to cognition, psychosocial functioning and quality of life. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2016;133:386–398. doi: 10.1111/acps.12535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bonnín CDM, Reinares M, Martínez-Arán A, Jiménez E, Sánchez-Moreno J, Solé B, Montejo L, Vieta E. Improving Functioning, Quality of Life, and Well-being in Patients With Bipolar Disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2019;22:467–477. doi: 10.1093/ijnp/pyz018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Etain B, Godin O, Boudebesse C, Aubin V, Azorin JM, Bellivier F, Bougerol T, Courtet P, Gard S, Kahn JP, Passerieux C FACE-BD collaborators, Leboyer M, Henry C. Sleep quality and emotional reactivity cluster in bipolar disorders and impact on functioning. Eur Psychiatry. 2017;45:190–197. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Murru A, Pacchiarotti I, Verdolini N, Reinares M, Torrent C, Geoffroy PA, Bellivier F, Llorca PM, Vieta E, Samalin L. Modifiable and non-modifiable factors associated with functional impairment during the inter-episodic periods of bipolar disorder. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2018;268:749–755. doi: 10.1007/s00406-017-0811-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Aref-Adib G, McCloud T, Ross J, O'Hanlon P, Appleton V, Rowe S, Murray E, Johnson S, Lobban F. Factors affecting implementation of digital health interventions for people with psychosis or bipolar disorder, and their family and friends: a systematic review. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6:257–266. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30302-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Au CH, Wong CS, Law CW, Wong MC, Chung KF. Self-stigma, stigma coping and functioning in remitted bipolar disorder. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2019;57:7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2018.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Williams TF, Simms LJ. Personality traits and maladaptivity: Unipolarity versus bipolarity. J Pers. 2018;86:888–901. doi: 10.1111/jopy.12363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Keshavarzpir Z, Seyedfatemi N, Mardani-Hamooleh M, Esmaeeli N, Boyd JE. The Effect of Psychoeducation on Internalized Stigma of the Hospitalized Patients with Bipolar Disorder: A Quasi-Experimental Study. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2021;42:79–86. doi: 10.1080/01612840.2020.1779881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Soni A, Singh P, Shah R, Bagotia S. Impact of Cognition and Clinical Factors on Functional Outcome in Patients with Bipolar Disorder. East Asian Arch Psychiatry. 2017;27:26–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Comes M, Rosa A, Reinares M, Torrent C, Vieta E. Functional Impairment in Older Adults With Bipolar Disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2017;205:443–447. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fresan A, Yoldi M, Morera D, Cruz L, Camarena B, Ortega H, Palars C, Martino D, Strejilevich S. Subsyndromal anxiety: Does it affect the quality of life? European J Psy. 2019;33:159–164. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Thomas SP, Nisha A, Varghese PJ. Disability and Quality of Life of Subjects with Bipolar Affective Disorder in Remission. Indian J Psychol Med. 2016;38:336–340. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.185941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mazzaia MC, Souza MA. Adherence to treatment in Bipolar Affective Disorder: perception of the user and the health professional. Port J Nurs Ment Heal . 2017:34–42. [Google Scholar]