Abstract

Background:

Surgical patients are vulnerable to opioid dependency and related risks. Clinical-translational data suggest that caffeine may enhance postoperative analgesia. This trial tested the hypothesis that intraoperative caffeine would reduce postoperative opioid consumption. The secondary objective was to assess whether caffeine improves neuropsychological recovery postoperatively.

Methods:

This was a single-center, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Participants, clinicians, research teams, and data analysts were all blinded to the intervention. Adult (≥18 years old) surgical patients (n=65) presenting for laparoscopic colorectal and gastrointestinal surgery were randomized to an intravenous caffeine citrate infusion (200 mg) or dextrose 5% in water (40 mL) during surgical closure. The primary outcome was cumulative opioid consumption through postoperative day three. Secondary outcomes included subjective pain reporting, observer-reported pain, delirium, Trail Making Test performance, depression and anxiety screens, and affect scores. Adverse events were reported, and hemodynamic profiles were also compared between groups.

Results:

Sixty patients were included in the final analysis, with 30 randomized to each group. The median (interquartile range) cumulative opioid consumption (oral morphine equivalents, mg) was 77 (33 – 182) mg for caffeine and 51 (15 – 117) mg for placebo (estimated difference, 55 mg; 95% confidence interval [CI], −9, 118; p=0.092). After post-hoc adjustment for baseline imbalances, caffeine was associated with increased opioid consumption (87 mg; 95% CI, 26, 148; p=0.005). There were otherwise no differences in pre-specified pain or neuropsychological outcomes between groups. No major adverse events were reported in relation to caffeine, and no major hemodynamic perturbations were observed with caffeine administration.

Conclusions:

Caffeine appears unlikely to reduce early postoperative opioid consumption. Caffeine otherwise appears well-tolerated during anesthetic emergence.

Introduction

Pain and neuropsychological impairment remain common and distressing complications after surgery. For example, moderate-to-severe pain occurs in up to 75% of patients after major surgery,1 and surgery is associated with an increased risk of prolonged opioid use compared to non-surgical controls.2 Both pain and opioids are also associated with neuropsychological dysfunction (e.g., cognitive impairment, depression), which is commonly reported in older surgical patients.3,4 Thus, surgical patients have high risk for adverse postoperative recovery given the inter-relationship and frequency of these perioperative complications.

Caffeine may serve as a promising intervention for improving pain and neuropsychological function after surgery. Basic science findings from a rat model demonstrate that caffeine confers acute analgesic benefit and reduces postoperative mechanical hypersensitivity, particularly in the setting of preoperative sleep deprivation.5 These findings align with a recent Cochrane Review, which found that caffeine provides analgesic benefit when given with ibuprofen after dental and obstetric surgery.6 Additionally, intravenous caffeine has been shown to accelerate emergence and neurocognitive recovery following general anesthesia in healthy volunteers.7 Likewise, caffeine improves neurocognitive function and increases arousal in the non-surgical setting.8,9 As such, caffeine serves as a plausible intervention for improving pain and neurocognitive recovery after surgery.

However, caffeine is not routinely given perioperatively, and additional, rigorous study is required in this setting. Evidence from the aforementioned Cochrane Review was graded as low-moderate quality, and trials were restricted to outpatient dental and obstetric surgery.6 Furthermore, while caffeine appears safe during anesthetic emergence in healthy volunteers, intravenous caffeine has not yet been tested during emergence after major surgery, where hemodynamic instability may be expected. Further testing is thus required to determine (1) the effects of caffeine on postoperative recovery profiles and (2) whether caffeine can be safely administered during this potentially high-risk period. Rigorous assessment methods are also required for determining such efficacy and safety endpoints. In this context, we conducted a quadruple-blinded, placebo-controlled, randomized trial to test the effects of caffeine on analgesic and neuropsychological recovery in a select group of surgical patients with similar recovery profiles (i.e., laparoscopic colorectal and gastrointestinal surgery). Given the postulated analgesic effects of caffeine, this trial tested the primary hypothesis that intraoperative caffeine would reduce postoperative opioid consumption. The secondary objective was to test the effects of caffeine on postoperative neuropsychological outcomes. Perioperative hemodynamic profiles and adverse events were also recorded. Lastly, physical function, mental health, and opioid use patterns were assessed 30 days after surgery.

Methods

Trial Design

The Caffeine, Pain, and Change in Outcomes after Surgery (CAPACHINOS) study was a randomized, placebo-controlled trial conducted at Michigan Medicine. The study was approved by the University of Michigan Medical School Institutional Review Board (HUM00135919), and written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrollment. The trial was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03577730, 7/5/2018, Principal Investigator: Vlisides) prior to trial initiation, and participants were enrolled from July 2018 to November 2019. The original trial protocol is available in Supplemental Digital Content 1, and expanded methods, protocol amendments, supplemental data, adverse events, protocol deviations, and the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) checklist are available in Supplemental Digital Content 2.

Participants were randomized in blocks of four stratified by age and sex (male ≥65 years old, male <65 years old, female ≥65 years old, female <65 years old) in a two-arm, parallel design with a 1:1 allocation ratio (placebo: caffeine). The randomization schedule and coding were held by the hospital research pharmacy, which was responsible for allocation concealment. The study drug was then delivered in a labeled syringe to the main OR pharmacy, where it was retrieved by the research study team. The trial was conducted in a quadruple-blinded fashion: participants, clinicians, research teams, and data analysts were all blinded to the intervention. Lastly, we elected to have independent internal audits of the trial by the Data and Study Monitoring Core of the Michigan Institute for Clinical and Health Research. The auditing team monitored informed consent documentation, data collection (e.g., accuracy, completion), regulatory compliance, and research pharmacy operations.

Study Population

Adult patients (≥18 years old) presenting for laparoscopic colorectal or gastrointestinal surgery were approached for study participation. This was a small trial with a relatively narrow surgical focus in order to minimize perioperative variability. These patients have similar anesthetic plans, surgical durations, postoperative opioid requirements, and hospital lengths of stay at our institution. Exclusion criteria were the following: emergency surgery, cognitive impairment precluding capacity for informed consent, uncontrolled cardiac arrhythmias, seizure disorders, intolerance or allergy to caffeine, preoperative opioid use, history of diabetes (because dextrose 5% in water [D5W] was the placebo), acute liver failure, pregnancy, breastfeeding, severe visual or auditory impairment (which might hinder cognitive function testing), patients unable to speak English, or enrollment in a conflicting research study.

Interventions

The hospital research pharmacy prepared intravenous solutions of D5W (placebo) or caffeine citrate (200 mg caffeine equivalent) per pharmacy standards and protocols, and the study drug was delivered directly to the operating room pharmacy prior to the surgery of enrolled participants. The dose of 200 mg was chosen based on prior investigations demonstrating analgesic efficacy with similar doses for select outpatient surgeries6 and postdural puncture headache.10,11 Additionally, no major adverse events were reported with similar doses in these trials. This safety consideration is important, given that caffeine was administered during a potentially high-risk period (i.e., anesthetic emergence). The study drug (40 mL dilution, D5W) was then infused over one hour, on a timed infusion pump, beginning at the initiation of surgical closure. This timing was chosen to evaluate the effects of caffeine on clinical and neurocognitive recovery in the immediate postoperative setting, including anesthetic emergence, as described in the following sections.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was opioid consumption, calculated in oral morphine equivalents, from the immediate postoperative period through postoperative day three (or discharge, whichever was sooner). Specifically, the total, cumulative consumption (as single number) during this time period represented the primary outcome. Opioid consumption was collected from electronic medical records and then converted to oral morphine equivalents using previously described methods.12

Secondary outcomes included the 10-centimeter Visual Analog Scale13 and Behavioral Pain Scale14 for subjective and objective pain assessment, respectively, along the same timeframe. Pain scores were measured at rest, with movement, and while taking a deep breath, twice daily, as we have done previously for dynamic pain analysis.12,15 Additional secondary outcomes included presence of delirium, which was assessed through the first three postoperative days using the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM).16 Cognitive function was analyzed preoperatively and in the postanesthesia care unit (PACU) one hour after caffeine administration using the Trail Making Test, which provides information on psychomotor speed, visual scanning, mental flexibility, and executive function.17 Depression and anxiety screens were assessed using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale,18 with scores ≥8 considered positive screens for both depression and anxiety scales. Affect was also assessed on a continuous scale using the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS).19 These scores were calculated at baseline and again on postoperative day three (or discharge, if sooner). The schedule of data collection is presented in Supplemental Digital Content 2, Table 1.

Exploratory outcomes included opioid consumption from postoperative days 4–7, incidence of self-reported sleep disturbances during hospitalization, persistent opioid use (yes/no) at postoperative day 30, and the Veterans RAND 12-Item Health Survey.20 Whole-scalp electroencephalographic oscillatory and connectivity patterns were also analyzed (see Supplemental Digital Content 2 for expanded methodology). Specifically, parietal electroencephalographic alpha power and frontal-parietal connectivity patterns were analyzed. These measures serve as candidate biomarkers of postoperative neurocognitive recovery, with increases in parietal alpha power and frontal-parietal connectivity correlating with return of neurocognitive function.21,22 Electroencephalographic data acquisition and analysis were conducted in a blinded fashion. Data were acquired from a resting, eyes-closed state. Based on electroencephalographic findings, PACU delirium and time until PACU discharge readiness were then analyzed as post-hoc exploratory outcomes. These outcomes are considered exploratory and hypothesis-generating.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed in SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC USA), MATLAB (version 2019b; MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA USA), and Power Analysis and Sample Size Software (PASS) (2020, NCSS, LLC. Kaysville, Utah, USA, ncss.com/software/pass). Exploratory data analysis techniques were used to assess the distribution of dependent measures for determining appropriate analytic strategies. There were no missing data for the primary outcome (opioid consumption) given the availability of inpatient medication administration records.

A Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) approach with exchangeable correlation matrix was used for assessing the primary outcome (i.e., total, cumulative opioid consumption, as a single number) through postoperative day three. This approach was an amended analysis plan, as the GEE approach with an exchangeable correlation structure can implicitly account for potential cross-sectional clustering (i.e., across surgeons).23 This strategy also allowed for construction of sequential models to adjust for baseline imbalances (defined by an absolute standardized difference >0.1) observed between groups (see Supplemental Digital Content 2, Protocol Amendments, for additional details). The GEE approach is also robust to non-normally distributed data, in the event that the distribution of cumulative opioid consumption data was found to be non-parametric.24 As such, this amended plan was incorporated after the data were accessed, but prior to data analysis and removal of the blind.

A separate, secondary analysis was also conducted for serial, longitudinal modeling of opioid consumption via the same GEE approach described above. This analysis was to conducted determine if the effects of caffeine varied over time, as was suggested by preliminary basic science data.5 Group (placebo vs. caffeine) and time served as fixed effects, and a group-by-time interaction term was included to assess the differences between caffeine and placebo response patterns over time. For both cumulative and longitudinal models, final results were assessed based on the best model selected using Likelihood Ratio tests and Akaike Information Criteria. Based on this strategy, the following final sequential models were constructed: (1) the above group and time specifications with the addition of demographic variables (e.g., age, sex, American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status score, and history of anxiety or depression) and (2) these demographic covariates in addition open surgical conversion (yes/no) and presence of Transversus Abdominis Plane block (yes/no). Anxiety and depression were incorporated given the independent association with opioid use disorder,2 open surgical conversion was included given the increased opioid consumption anticipated with open conversion to laparotomy. This strategy was implemented given group imbalances within these categories (as outlined in Results). Lastly, the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure for p-value adjustment25 was incorporated for reducing the False Discovery Rate across time points for longitudinal modeling. For secondary endpoints, continuous data were analyzed using Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney U test, as appropriate. Categorical data were analyzed using chi-squared or Fisher’s Exact tests, as appropriate. Subjective and objective pain measures were analyzed via mixed effects models to assess changes in pain scores over time within the trial populations. The threshold for significance was set to p<0.05 across all tests.

Based on similar trials assessing analgesic efficacy and neuropsychological effects of caffeine,26–29 60 patients were recruited for this trial. Group sample sizes of 30 and 30 achieve >80% power to reject the null hypothesis of zero effect size when the population effect size is 0.75 and the significance level is 0.05 using a two-sided, two-sample equal variance t-test.

Results

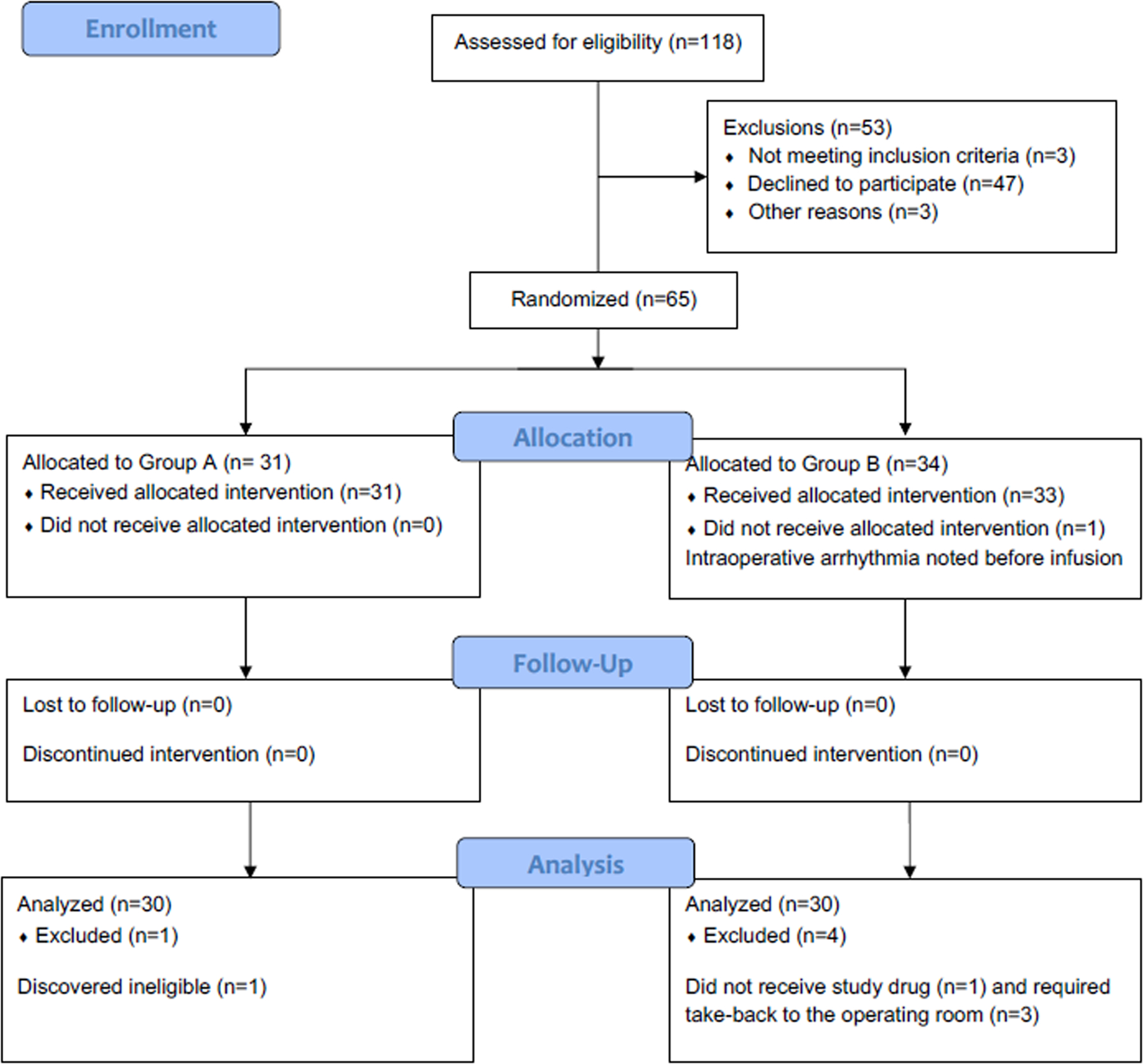

The CONSORT study flow diagram is presented in Figure 1. Enrollment took place between July 10, 2018 and November 14, 2019. Baseline patient characteristics and group imbalances (based on absolute standardized differences >10%), are presented in Table 1. The majority of patients underwent colorectal surgery. Intraoperative analgesic profiles are presented in Supplemental Digital Content 2, Table 2. Final results are presented for 60 patients as outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram presented. CONSORT, Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| Placebo (N = 30) |

Caffeine (N = 30) |

Absolute Standardized Difference (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 50 ± 18 | 54 ± 17 | 19 |

| Male sex | 15 (50) | 13 (43) | 13 |

| Weight, mean (SD), kg | 81 ± 17 | 81 ± 21 | 0 |

| Race | 26 | ||

| White | 30 (100) | 29 (97) | |

| Asian | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3) | |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 1 (3) | 2 (7) | 15 |

| College education or higher | 16 (53) | 17 (57) | 7 |

| ASA classification | 43 | ||

| I | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | |

| II | 21 (70) | 17 (57) | |

| III | 8 (27) | 13 (43) | |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Anxiety | 7 (23) | 4 (13) | 26 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | -- |

| Coronary artery disease | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | -- |

| Cerebrovascular Disease | 2 (7) | 0 (0) | -- |

| Congestive Heart Failure | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | -- |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | -- |

| COPD | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | -- |

| Crohn’s disease | 3 (10) | 5 (17) | 20 |

| Depression | 6 (20) | 3 (10) | 28 |

| Hypertension | 7 (23) | 8 (27) | 8 |

| Malignancy | 16 (53) | 18 (60) | 14 |

| Obstructive Sleep Apnea | 7 (23) | 4 (13) | 26 |

| Ulcerative colitis | 5 (17) | 5 (17) | 0 |

| Surgical Procedure | 10 | ||

| Colorectal | 29 (97) | 27 (90) | |

| Small bowel | 1 (3) | 3 (10) | |

| Baseline Scores | |||

| Pain* – resting, median (IQR), mm | 0 [0 – 10] | 0 [0 – 6] | 2 |

| Pain* – deep breath, median (IQR), mm | 0 [0 – 5] | 0 [0 – 1] | 4 |

| Pain* – movement, median (IQR), mm | 12 [4 – 23] | 0 [0 – 14] | 31 |

| PANAS – Positive, median (IQR), score (n) | 32 [29 – 37] | 32 [29 – 41] | 22 |

| PANAS – Negative, median (IQR), score (n) | 16 [12 – 19] | 16 [13 – 21] | 16 |

| RCSQ, mean (SD), score (n) | 56 (28) | 58 (26) | 9 |

| Caffeine Intake† – median (IQR) | 2 [1 – 3] | 2 [1 – 2] | 24 |

Data are presented as number (percentage) unless otherwise specified.

Pain reflects self-reported score (0–100 mm) on the Visual Analog Scale.

Caffeine intake reflects the number of self-reported caffeinated beverages per day at baseline. Of note, absolute standardized differences were not calculated for atrial fibrillation, coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, congestive heart failure, chronic kidney disease, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease due to small sample size.

Abbreviations: ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologist; COPD, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; APR, abdominoperineal resection; PANAS, Positive and Negative Affect Schedule; HADS = Hospitalized Anxiety and Depression Scale; RCSQ = Richards-Campbell Sleep Questionnaire.

Primary Outcome

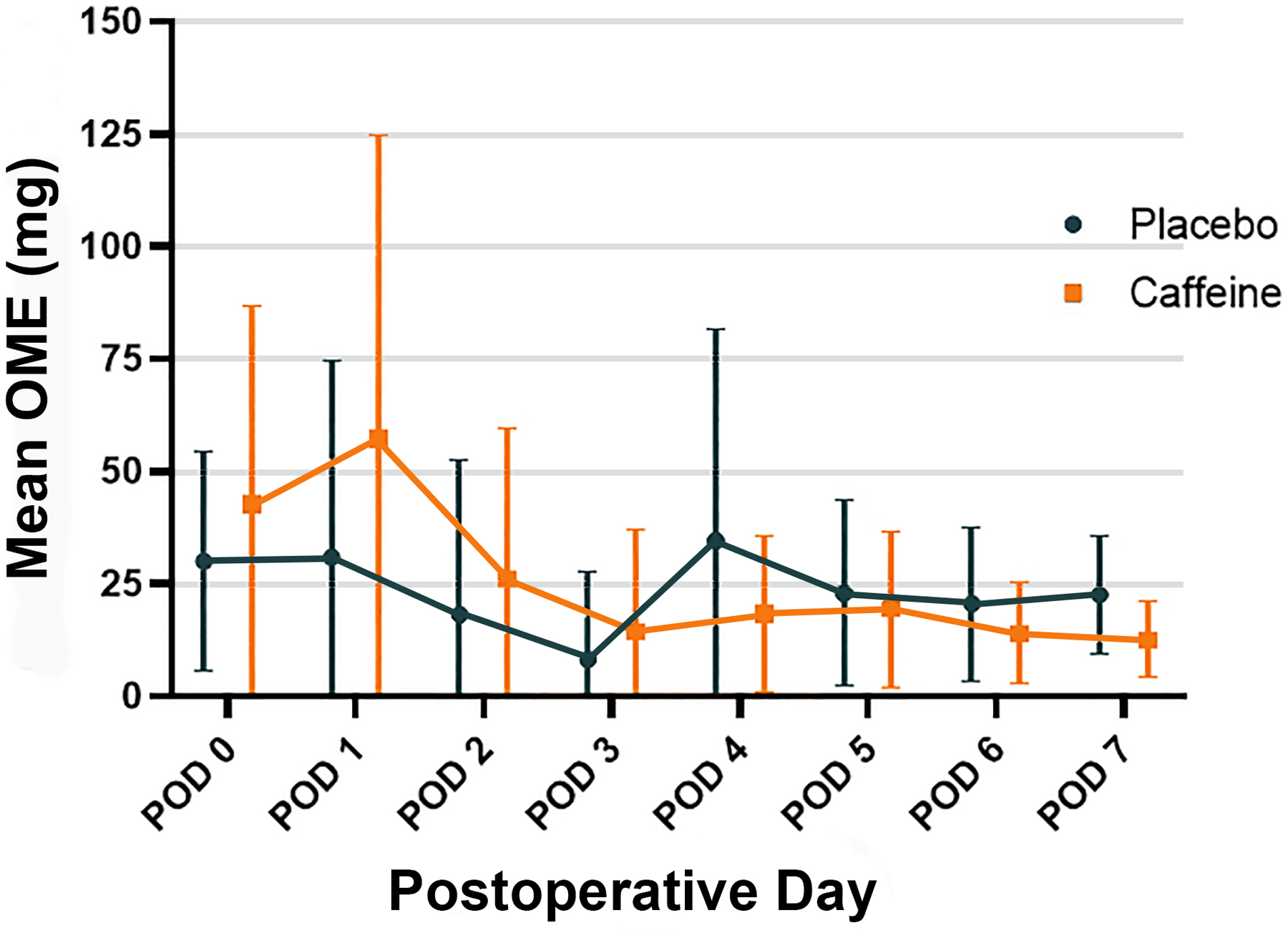

For the primary outcome, i.e., cumulative opioid consumption (oral morphine equivalents, mg) through postoperative day three (or day of discharge), there was no significant difference between the caffeine (median [± interquartile range]) (77 [33 – 182] mg) and placebo (51 [15 – 117] mg) groups based on unadjusted group comparisons (estimated difference, 55 mg; 95% confidence interval [CI], −9, 118; p=0.092) (Table 2). After post-hoc adjustments for age, sex, American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status score, history of anxiety or depression, and open surgical conversion, caffeine was associated with significantly increased opioid consumption, (87 mg; 95% CI, 26, 148; p=0.005). In terms of the secondary analysis, assessing the longitudinal effects of caffeine over time, there was no significant group-by-time interaction with longitudinal modeling. Opioid consumption throughout the entire postoperative period is presented in Figure 2 and Supplemental Digital Content 2, Table 3.

Table 2.

Effects of Caffeine on Clinical Outcomes

| Placebo (n=30) |

Caffeine (n=30) |

Difference (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome | ||||

| Opioid Consumption (oral morphine equivalents, mg)* | 51 (15 – 117) | 77 (33 – 182) | −26 (−91, 40) | 0.165 |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||

| Delirium, n (%) (n=60) | 14 (47) | 7 (23) | 23 (0, 47) | 0.058 |

| Trail Making Test A | ||||

| Baseline, s (n=28) | 23 (18 – 34) | 25 (20 – 31) | −2 (−13, 9) | |

| PACU, s (n=28) | 42 (34 – 70) | 39 (23 – 56) | 3 (−21, 27) | 0.268 |

| Difference from baseline, s (n=28) | 16 (6 – 39) | 10 (2 – 25) | 6 (−15, 26) | 0.417 |

| Trail Making Test B | ||||

| Baseline, s (n=28) | 45 (37 – 74) | 60 (42 – 71) | −15 (−40, 9) | |

| PACU, s (n=28) | 100 (61 – 215) | 79 (56 – 134) | 21 (−67, 109) | 0.487 |

| Difference from baseline, s (n=28) | 22 (6 – 110) | 23 (14 – 69) | −1 (−60, 58) | 0.798 |

| HADS-Depression | ||||

| Baseline (n=60) | 2 (1 – 5) | 2 (0 – 4) | 0 (−2, 2) | |

| Postoperative (n=55) | 3 (2 – 5) | 2 (1 – 5) | 1 (−1, 3) | 0.165 |

| New positive screen, no. (%) (n=55) | 1 (4) | 2 (7) | 0 (0, 0) | 0.595 |

| HADS-Anxiety | ||||

| Baseline (n=60) | 7 (4 – 9) | 5 (3 – 8) | 2 (−1, 5) | |

| Postoperative (n=55) | 4 (1 – 7) | 3 (1 – 6) | 1 (−2, 4) | 0.254 |

| New positive screen, n (%) (n=55) | 2 (7) | 2 (7) | 0 (0, 0) | 0.985 |

| PANAS – Positive Affect | ||||

| Baseline (n=53) | 32 (29 – 37) | 32 (29 – 41) | 0 (−5, 5) | |

| Postoperative (n=53) | 35 (27 – 37) | 35 (28 – 39) | 0 (−5, 5) | 0.432 |

| Difference from baseline (n=53) | 0 (−6 – 5) | 1 (−4 – 5) | −1 (−6, 4) | 0.756 |

| PANAS – Negative Affect | ||||

| Baseline (n=53) | 16 (12 – 19) | 15 (12 – 20) | 1 (−3, 5) | |

| Postoperative (n=53) | 12 (10 – 17) | 12 (10 – 16) | 0 (−3, 3) | 0.673 |

| Difference from baseline (n=53) | −2 (−3, −1) | −2 (−5 – 0) | 0 (−2, 2) | 0.594 |

Cumulative consumption, postoperative days 1–3, unadjusted for group imbalances with Mann-Whitney U p-value results reported. Baseline anxiety, depression, and affect assessments were performed prior to surgery, and postoperative assessments were performed on postoperative day three or day of discharge, whichever was sooner. Categorical data were analyzed via Chi-Square Test or Fisher’s Exact Test, and continuous data were analysed via Independent T-test (parametric data) or Mann-Whitney U test (non-parametric data). Data presented as mean (SD) or median (IQR) as appropriate, unless otherwise indicated. For tests that include differences from baseline (e.g., Trail Making Tests), baseline statistics are only presented for participants who also had a postoperative score for comparisons.

Abbreviations: PACU, postanesthesia care unit; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; PANAS, Positive and Negative Affect Schedule.

Figure 2.

Mean opioid consumption presented over the first seven postoperative days. Error bars represent standard deviation. OME, oral morphine equivalents. POD, postoperative day.

Pre-Specified Secondary Outcomes

Through the first three postoperative days, there was no significant difference between groups in terms of Visual Analog Scale pain score (0–100 mm) at rest, (0.1 mm; 95% CI, −0.8, 1.0; p=0.802), with deep breathing (−0.8 mm; 95% CI, −9.4, 7.8; p=0.861), or with movement (−6.5 mm; 95% CI, −17, 4.1; p=0.229) (Supplemental Digital Content 2, Table 4). Similarly, there was no significant difference between groups for the observer-rated Behavioral Pain Scale (3–12, n) (0.01; 95% CI, −0.01, 0.02; p=0.320) (Supplemental Digital Content 2, Table 5). There were no significant interactions between group and time for any of the visual or behavioral pain scale measures.

In terms of neuropsychological outcomes, there was no statistically significant difference in postoperative delirium incidence (i.e., PACU through postoperative day three) or PACU Trail Making Test Scores (Table 2). Likewise, there was no difference in the proportion of new positive postoperative screens for depression or anxiety, and perioperative PANAS scores were similar between groups (Table 2). Lastly, time between the end of surgical closure and anesthetic emergence (minutes) was similar between placebo (10 [6 – 17]) and caffeine (8 [6 – 15]; p=0.670) groups.

Exploratory Analysis

Longitudinal analysis was conducted to compare opioid consumption between groups for postoperative days 4–7. There were no significant differences between groups over time (Supplemental Digital Content 2, Table 3). Self-reported sleep disturbances, incidence of persistent opioid use by 30 days post-discharge, and Veterans Rand 12-item survey scores post-discharge were similar between groups as well (Supplemental Digital Content 2, Table 6).

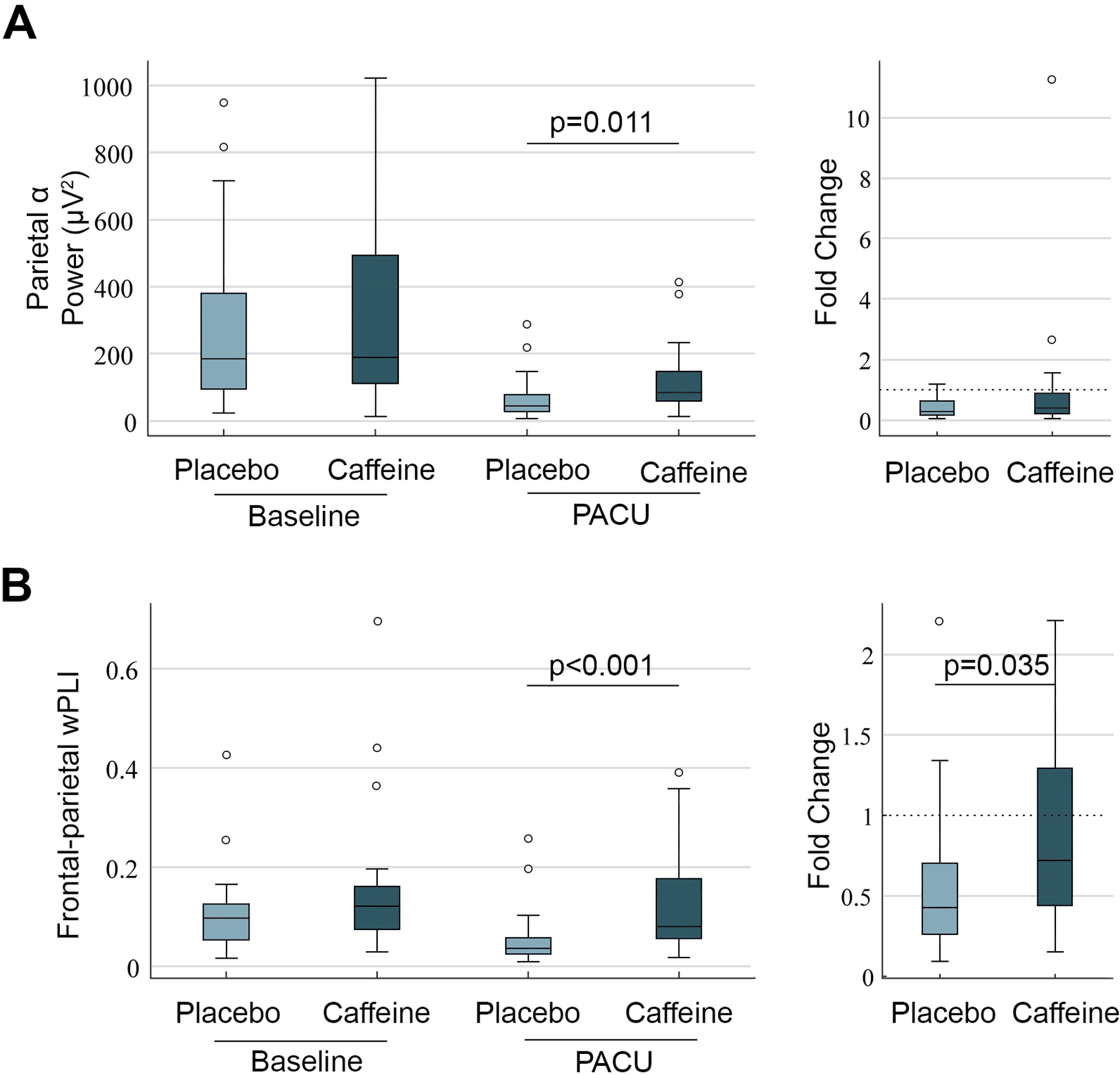

An expanded exploratory analysis was also conducted to characterize electroencephalographic patterns between groups. Given the difficulty with obtaining whole-scalp perioperative electroencephalographic data, all available randomized patients (n=65) were included for review. Of note, the additional five randomized patients were excluded from the primary analysis due to reasons that would confound pain assessment (e.g., preoperative tramadol use, surgical take-back on postoperative days 2–3) and due to a new arrhythmia during closure; Figure 1), rather than PACU neurophysiology. Analysis was performed for 26 patients in the caffeine group and 26 in the placebo group based on data quality. Mean (standard deviation) time between extubation and PACU electroencephalogram recordings was 20 (± 10) minutes in the caffeine group and 19 (± 11) minutes in the placebo group (p=0.711). Electroencephalographic analysis revealed increased parietal alpha power (decibels, dB) in the caffeine group (19 dB [18 – 22]) compared to placebo (17 dB [14 – 19], p=0.011) (Figure 3). Similarly, PACU alpha frontal-parietal connectivity (weighted phase lag index) was significantly higher in the caffeine group (0.08 [(0.06 – 0.18]) compared to placebo (0.04 [0.03 – 0.06], p<0.001). After incorporating baseline values, frontal-parietal connectivity fold-change (median [interquartile range]) from baseline was significantly higher in the caffeine group (0.72 [0.44 – 1.29]) compared to placebo (0.48 [0.27 – 0.72]) (Figure 3). Based on these findings, a post-hoc exploratory analysis was then conducted to assess PACU delirium incidence and time until PACU discharge readiness between groups. PACU delirium was significantly lower in the caffeine group (4/34, 12% vs. 10/31, 33%, p=0.04). Time until PACU discharge readiness (minutes) was similar between placebo (72 [62 – 108]) and caffeine (67 [56 – 94) groups (p=0.302). These were post-hoc exploratory outcomes that should be viewed as hypothesis-generating.

Figure 3.

(A) Parietal electroencephalographic alpha power presented at preoperative baseline and in the postanesthesia care unit (PACU) for both groups. Parietal alpha power was significantly higher in the caffeine group (n=26) compared to placebo (n=26) during PACU assessment. (B) Frontal-parietal cortical connectivity, assessed via weighted phase lag index, presented over the same time period. The caffeine group demonstrated higher weighted phase lag index in the PACU, similar to parietal alpha power. Weighted phase lag index change from baseline (based on fold-change) was significantly higher in the caffeine group.

Hemodynamic Profiles and Adverse Events

No patients in the caffeine group required anti-hypertensive administration during emergence or PACU admission. Likewise, no new arrhythmias were reported in the caffeine group, and hemodynamic profiles were similar between groups during PACU admission (Supplemental Digital Content 2, Table 7). The majority of adverse events were mild-to-moderate and unlikely to be related to caffeine administration. Serious adverse events, such as postoperative hemorrhage, infection, and bowel obstruction were unlikely to be related to caffeine (Supplemental Digital Content 2, Table 8).

Discussion

Contrary to our hypothesis, this single-center clinical trial provides evidence for increased postoperative opioid consumption associated with intraoperative caffeine administration. There was no difference in subjective pain reporting or objective pain scores postoperatively, and positive screens for postoperative anxiety and depression were similar (and low) between groups. Incidence of postoperative delirium (from PACU through postoperative day three) and cognitive function scores were also similar between groups. Exploratory analysis revealed increased markers of neurophysiologic recovery in the caffeine group based on electroencephalographic analysis. PACU length of stay and post-discharge outcomes were otherwise similar between groups. Caffeine was otherwise well-tolerated overall without major side effects.

Patients often report severe pain after surgery, prompting opioid administration. Pain and opioids can both increase depressive symptoms, and mental health disorders increase risk for chronic opioid use after surgery.2,30 Surgical patients are thus vulnerable to entering this refractory cycle postoperatively. Caffeine represents a neurobiologically informed intervention for disrupting this cycle, as caffeine may simultaneously enhance postoperative analgesia5 and neuropsychological function.8 However, in this trial, adjusted analysis revealed increased opioid consumption associated with caffeine administration. One explanation may be that caffeine increases early postoperative arousal, which could heighten awareness of pain at a time when severity might be worst (i.e., immediately after surgery). Indeed, increased opioid consumption occurred in association with increased electroencephalographic signs of neurocognitive recovery. Alternatively, the effects of caffeine may differ depending on the type of surgery. Data from a previous meta-analysis suggest that caffeine demonstrates analgesic efficacy in the hours after dental and gynecological surgery.31 Analgesic effects may also vary based on dose, as 100 mg was the most common dose used in these trials,31 which is slightly lower than the dose used in our present study. Future trials can further test these possibilities. Lastly, basic science data suggest that caffeine reduces hyperalgesia after postoperative day three via effects on sleep-wake networks.5 No significant differences in opioid consumption were found between groups after postoperative day three, and sleep disturbance profiles were also similar through the first three postoperative days. One explanation may be that a single dose of caffeine, administered intraoperatively, does not impact nociception beyond the immediate postoperative setting. Alternatively, a larger, more rigorous analysis of post-discharge opioid consumption may be required to detect any analgesic effects conferred by caffeine.

In terms of neuropsychological outcomes, caffeine was also tested in relation to cognition, depressive symptoms, anxiety, and affect. Caffeine enhances mood, arousal, and cognitive function across various settings,8 and epidemiological data suggest that caffeine decreases depression risk in a dose-dependent manner.32 Caffeine may thus plausibly impact neuropsychological function perioperatively. However, no effects were observed regarding cognitive or behavioral outcomes. Likewise, 30-day physical and mental health scores were similar between caffeine and placebo groups. One possibility is that any effects conferred by caffeine were restricted to the immediate postoperative setting. Indeed, the caffeine group demonstrated increased frontal-parietal connectivity and posterior alpha power in the PACU, suggesting increased neurophysiologic arousal and return of neurocognitive function.21,22 A post-hoc, exploratory analysis revealed reduced PACU delirium concurrent with these electroencephalographic changes. This is an exploratory, hypothesis-generating finding, but caffeine may nonetheless improve early neurocognitive recovery after surgery given that caffeine increases arousal and can enhance cognitive function.8

Multiple strengths of this study are worth highlighting. This was a randomized, placebo-controlled trial in which research teams, patients, clinicians, and statistical analysts were blinded to group allocation. The blind was lifted only after the statistical analysis was completed. Pain outcomes were reported in a multidimensional manner. In addition to longitudinal modeling of opioid consumption, subjective pain was dynamically measured (e.g., during deep breaths, movement), and observer-based pain scoring was also reported. The neuropsychological and functional outcome tools chosen are widely used, validated instruments that lend themselves to reproducibility. Furthermore, electroencephalography was utilized as a measure of brain function and provided direct neurophysiological data on recovery that is independent of clinical observation. Lastly, internal and independent auditing was performed by the Michigan Institute of Clinical and Health Research, our NIH-funded clinical-translational sciences institute. Overall, these study design elements helped to strengthen trial rigor.

Important limitations are worth noting as well. The sample size was relatively small, as this single-center trial was powered for detecting a relatively large effect size. The small sample size may have also driven group imbalances at baseline (Table 1, Supplemental Digital Content 2, Table 2). We were unable to adjust for all baseline and intraoperative imbalances given the limited number of degrees of freedom allowable in regression models. The relatively narrow eligibility criteria reflect the explanatory nature of the trial and may limit generalizability to other patient populations. Chronic pain patients and those with opioid tolerance, for example, were excluded from the trial. The fixed dose is another limitation of the current trial. As described previously, the fixed dose was chosen with analgesic efficacy and safety considerations in mind. Nonetheless, weight-based dosing was not utilized, though this strategy can be considered for future trials. Although adjusted opioid administration was increased in the caffeine group, reasons for this increase were not analyzed. There are additional outcomes relevant to caffeine intake, such as perioperative headache and overall quality of recovery, that were not reported in this trial. Future trials could also consider multiple dosing arms to better understand the causative effects of perioperative caffeine administration and opioid consumption. Lastly, analysis of safety endpoints is limited given the small sample size, though no major adverse events were reported in relation to caffeine, and hemodynamic profiles were similar between placebo and caffeine groups.

In conclusion, caffeine appears unlikely to decrease early postoperative opioid consumption. There were otherwise no differences in neuropsychological outcomes or 30-day exploratory outcomes between groups, though caffeine may enhance neurophysiological arousal after surgery.

Supplementary Material

Key Points.

Question:

Does intraoperative caffeine administration reduce postoperative opioid consumption?

Findings:

In a single-center randomized controlled trial, intraoperative caffeine was associated with increased postoperative opioid consumption after adjustment for baseline imbalances.

Meaning:

Intraoperative caffeine appears unlikely to reduce early postoperative opioid consumption.

Acknowledgements:

We would to thank Kathy Richards, PhD, RN, FAAN, Research Professor, Senior Research Scientist, School of Nursing, University of Texas (Austin, TX USA) for Richards Campbell Sleep Questionnaire permissions.

Disclosure of Funding:

Supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health Grant (K23GM126317), Michigan Institute for Clinical and Health Research (UL1TR02240), and the Department of Anesthesiology, University of Michigan Medical School. Funding agencies had no role in study design, operations, or analysis.

Glossary of Terms

- CAM

Confusion Assessment Method

- CAPACHINOS

Caffeine, Pain, and Change in Outcomes after Surgery

- CONSORT

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials

- D5W

Dextrose 5% in water

- GEE

Generalized Estimating Equations

- OME

Oral Morphine Equivalent

- PACU

Postanesthesia Care Unit

- PANAS

Positive and Negative Affect Schedule

- PASS

Power Analysis and Sample Size Software

- POD

Postoperative Day

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None

Clinical Trial Number: NCT03577730 (ClinicalTrials.gov)

References

- 1.Gan TJ, Habib AS, Miller TE, White W, Apfelbaum JL. Incidence, patient satisfaction, and perceptions of post-surgical pain: Results from a US national survey. Curr Med Res Opin 2014;30:149–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brummett CM, Waljee JF, Goesling J et al. New persistent opioid use after minor and major surgical procedures in us adults. JAMA Surg 2017;152:e170504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lenze EJ, Munin MC, Skidmore ER et al. Onset of depression in elderly persons after hip fracture: implications for prevention and early intervention of late-life depression. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007;55:81–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park S, Kang CH, Hwang Y et al. Risk factors for postoperative anxiety and depression after surgical treatment for lung cancer. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2016;49:e16–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hambrecht-Wiedbusch VS, Gabel M, Liu LJ, Imperial JP, Colmenero AV, Vanini G. Preemptive caffeine administration blocks the increase in postoperative pain caused by previous sleep loss in the rat: a potential role for preoptic adenosine A2A receptors in sleep-pain interactions. Sleep 2017;40. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Derry S, Wiffen PJ, Moore RA. Single dose oral ibuprofen plus caffeine for acute postoperative pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015:Cd011509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Fong R, Wang L, Zacny JP et al. Caffeine accelerates emergence from isoflurane anesthesia in humans: a randomized, double-blind, crossover study. Anesthesiology 2018;129:912–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McLellan TM, Caldwell JA, Lieberman HR. A review of caffeine’s effects on cognitive, physical and occupational performance. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2016;71:294–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Landolt HP, Werth E, Borbely AA, Dijk DJ. Caffeine intake (200 mg) in the morning affects human sleep and EEG power spectra at night. Brain Res 1995;675:67–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yucel A, Ozyalcin S, Talu GK, Yucel EC, Erdine S. Intravenous administration of caffeine sodium benzoate for postdural puncture headache. Reg Anesth Pain Med 1999;24:51–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zeger W, Younggren B, Smith L. Comparison of cosyntropin versus caffeine for post-dural puncture headaches: a randomized double-blind trial. World J Emerg Med 2012;3:182–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Avidan MS, Maybrier HR, Abdallah AB et al. Intraoperative ketamine for prevention of postoperative delirium or pain after major surgery in older adults: an international, multicentre, double-blind, randomised clinical trial. Lancet 2017;390:267–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kjeldsen HB, Klausen TW, Rosenberg J. Preferred presentation of the visual analog scale for measurement of postoperative pain. Pain Pract 2016;8 980–984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chanques G, Payen JF, Mercier G et al. Assessing pain in non-intubated critically ill patients unable to self report: an adaptation of the behavioral pain scale. Intensive Care Med 2009;35:2060–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Avidan MS, Fritz BA, Maybrier HR et al. The prevention of delirium and complications associated with surgical treatments (PODCAST) study: Protocol for an international multicentre randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2014;4:e005651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inouye SK, van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, Balkin S, Siegal AP, Horwitz RI. Clarifying confusion: the Confusion Assessment Method. a new method for detection of delirium. Ann Intern Med 1990;113:941–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tombaugh TN. Trail Making Test A and B: Normative data stratified by age and education. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 2004;19:203–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;67:361–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol 1988;54:1063–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Selim AJ, Rogers W, Fleishman JA et al. Updated U.S. Population standard for the Veterans Rand 12-item health survey (VR-12). Qual Life Res 2009;18:43–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blain-Moraes S, Tarnal V, Vanini G et al. Network efficiency and posterior alpha patterns are markers of recovery from general anesthesia: a high-density electroencephalography study in healthy volunteers. Front Hum Neurosci 2017;11:328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Telesford QK, Lynall ME, Vettel J, Miller MB, Grafton ST, Bassett DS. Detection of functional brain network reconfiguration during task-driven cognitive states. Neuroimage 2016;142:198–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McNeish D, Stapleton LM. Modeling clustered data with very few clusters. Multivariate Behav Res 2016;51:495–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pekar S, Brabe M. Generalized estimating equations: a pragmatic and flexible approach to the marginal GLM modelling of correlated data in the behavioural sciences. Ethology 2017;124:86–93. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 26.McQuay HJ, Angell K, Carroll D, Moore RA, Juniper RP. Ibuprofen compared with ibuprofen plus caffeine after third molar surgery. Pain 1996;66:247–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baratloo A, Mirbaha S, Delavar Kasmaei H, Payandemehr P, Elmaraezy A, Negida A. Intravenous caffeine citrate vs. magnesium sulfate for reducing pain in patients with acute migraine headache; a prospective quasi-experimental study. Korean J Pain 2017;30:176–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Camann WR, Murray RS, Mushlin PS, Lambert DH. Effects of oral caffeine on postdural puncture headache. a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Anesth Analg 1990;70:181–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haskell CF, Kennedy DO, Wesnes KA, Scholey AB. Cognitive and mood improvements of caffeine in habitual consumers and habitual non-consumers of caffeine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;179:813–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun EC, Darnall BD, Baker LC, Mackey S. Incidence of and risk factors for chronic opioid use among opioid-naive patients in the postoperative period. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176:1286–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Derry S, Wiffen PJ, Moore RA. Single dose oral ibuprofen plus caffeine for acute postoperative pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;2015:Cd011509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lucas M, Mirzaei F, Pan A et al. Coffee, caffeine, and risk of depression among women. Arch Intern Med 2011;171:1571–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.