Abstract

Background

Previous database studies have found gender disparities favoring men in rates of liver transplantation, which resolve in cohorts examining only patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Aims

Our study aims to use two large, multicenter United States (US) databases to assess for gender disparity in HCC treatment regardless of transplant listing status.

Methods

We performed a retrospective database analysis of inpatient admission data from the University Health Consortium (UHC) and the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS), over a 9- and 10-year period, respectively. Adults with a primary discharge diagnosis of HCC, identified using the International Classification of Diseases 9th Edition (ICD-9) code, were included. Series of univariate and multivariate analyses were performed to examine gender disparities in metastasis, liver decompensation, treatment type, and inpatient mortality after controlling for other possible predictors.

Results

We included 26,054 discharges from the NIS database and 25,671 patients from the UHC database in the analysis. Women with HCC appear to present less often with decompensated liver disease (OR = 0.79, p < 0.001). Furthermore they are more likely to receive invasive HCC treatment, with significantly higher rates of resection across race and diagnoses (OR = 1.34 and 1.44, p < 0.001). Univariate analyses show that US women have lower unadjusted rates of transplant; however, the disparity resolves after controlling for other clinical and demographic factors.

Conclusions

US women more often receive invasive treatment for HCC (especially resection) than US men with no observed disparity in transplantation rates when adjusted for pre-treatment variables.

Keywords: Resection, Hepatocellular carcinoma, Gender, Disparities

Introduction

Primary liver cancer is the fifth most common cancer in men and the seventh in women, and the third most common cause of cancer death worldwide [1]. Approximately 20,000 new cases of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) are diagnosed each year in the United States (US) and the incidence is two to four times higher in men than in women [2]. The incidence continues to rise, largely due to the prevalence of infection with hepatitis C virus (HCV), and HCV-related HCC has been the fastest-rising cause of cancer deaths in the US in recent decades [2]. Other risk factors for HCC include infection with hepatitis B virus (HBV), alcoholic liver disease, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, as well as genetic and autoimmune disease, most of which lead to HCC through the development of cirrhosis [2]. The risk of developing HCC in a cirrhotic patient varies, but is roughly 4–30 % over 5 years depending on the etiology and stage of liver disease as well as patient factors, such as ethnicity [3]. For patients with HCV, the risk of HCC is highest in patients with older age, African-American race, lower platelet counts, higher alkaline phosphatase, higher elastography values, esophageal varices, and biopsy staining showing high proliferative activity [4]. Alcohol and metabolic risk factors such as diabetes and obesity have a synergistic effect with viral hepatitides in promoting HCC [4]. Across all etiologies, HCC is more common in men, which is suggested to be due to both increased exposure to risk factors as well as protective qualities of estrogen [1, 4]. When HCC is detected at an early stage, curative treatments are available.

The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) published guidelines in 2005 with updates in 2011 that outline surveillance recommendations. According to their guidelines, ultrasound exam should be performed every 6 months in patients with cirrhosis from various causes including hepatitis C virus as well as for cirrhotic and specific non-cirrhotic populations with hepatitis B virus [5, 6]. Nodules detected by ultrasound should undergo a dynamic cross sectional imaging test for diagnosis if they are greater than 1 cm in diameter or follow-up ultrasounds to assess for stability if they are less than 1 cm in diameter [5, 6]. The most widely accepted staging system for HCC is the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging and treatment strategy. Currently, this system stratifies patients into 5 categories (0: very early, A: early, B: intermediate, C: advanced and D: terminal) based on a combination of liver function, tumor stage, and patient performance status [4, 7]. Curative treatments for HCC include resection for solitary tumors in patients with well compensated liver disease or liver transplantation for patients with tumors falling within Milan criteria and evidence of hepatic decompensation. Patients who undergo resection for HCC have a risk of recurrence of HCC of up to 80 % at 5 years because of the continued presence of the underlying liver disease [2, 4]. In the US, less than 5 % of tumors are eligible for resection [2]. Locoregional treatments include radiofrequency ablation (RFA) and transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) for intermediate stage cancers and oral sorafenib for tumors that have advanced beyond the reach of locoregional or surgical treatment [2]. Unfortunately, despite these therapies, the 5-year survival in the US has remained less than 12 % [2].

As liver transplant offers one of the only curative options for HCC, its use has been examined in several studies. Prior to the introduction of the MELD (Model for Endstage Liver Disease) score as the basis for organ allocation in liver transplant in 2002, both gender and racial disparities existed in rates of liver transplantation with women and blacks less likely to receive an organ within the three-year period following listing for liver transplantation [8]. After the introduction of the MELD, the racial disparity in transplant rates disappeared, but the gender disparity persisted. In addition, women became more likely than men to die or become too sick to transplant while waiting for an organ. However, MELD exception points are granted to patients with HCC listed for transplant and, in cohort analyses of patients with HCC, rates of transplantation between men and women were not significantly different [8]. These studies have all relied on transplant specific databases and do not evaluate the gender-based trends in US HCC treatment at large. The aim of our study was to use a nationwide database of patients diagnosed with HCC to examine whether gender disparities exist in the treatment of HCC in the United States.

Methods

Data Source

We examined two nationwide datasets of comparable quality for our study: the University Health Consortium (UHC) and the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS). The UHC database is a clinical and administrative database of all payers’ discharge records compiled from 112 academic medical centers and 256 of their affiliated hospitals in 42 states, representing approximately 90 % of the nation’s non-profit academic medical centers [9]. The UHC database contains unique identifiers for each patient, thus discharges can be linked to the patient. The NIS is a component of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) [10], sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare and Quality. This database represents the largest inpatient database in the United States. The NIS represents a stratified sampling of US hospitals including public hospitals, children’s hospitals, and academic medical centers. The database contains data from 1,050 hospitals with more than eight million discharges annually. The NIS does not contain a unique identifier for patients; thus discharges cannot be linked to the patient level. Subsequently, the unit of observation in NIS data is hospital discharge while the unit of observation for UHC is the patient.

Data was obtained over a period of 9 years (third quarter of 2002 to the third quarter of 2011) from the UHC database and over a period of 10 years (2000–2009) from the NIS database. In the analysis of both databases we included admissions made by adults with a primary discharge diagnosis of HCC, identified using the International Classification of Diseases 9th Edition (ICD-9) code (155.0). We excluded admissions (NIS database) or patients (UHC database) with other primary non-hepatic tumors or those with secondary liver cancer tumors by ICD-9 code.

In each case we collected data on demographics (age at admission, sex and race), primary payer, geographic location of the hospital, discharge year, HCC risk factors, features of liver decompensation, the presence of extra-hepatic metastases (identified using the specific ICD-9 codes for secondary tumors), comorbidities, and treatment type.

Age was grouped into three levels (≤64, 65–79 and ≥80). Discharge year was classified into two groups, those before and those after 2005. ICD-9 codes were used to identify HCC risk factors (HCV, HBV, alcohol abuse, HCV and alcohol abuse, unknown) and to identify the degree of decompensated liver disease (ascites, portal hypertension, esophageal varices, hepatorenal syndrome, coagulopathy, edema and encephalopathy). Features of liver decompensation were grouped into four categories (0, 1, 2, and 3 or more features) based on the number of features coded. Comorbidities (by ICD-9 code) were itemized and used to calculate a modified Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) [11]. The CCI is a global measure of comorbidities that is calculated for patients according to the presence of four atherosclerotic comorbidities of peripheral arterial disease, myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular disease, and congestive heart failure, and 13 non-athero-sclerotic comorbid conditions, including diabetes mellitus with and without complication, chronic lung disease, gastrointestinal ulcer, arthritis, paraplegia, renal failure, malignancy (with and without metastasis), acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, dementia, liver disease, and liver failure. CCI has been validated for use in administrative databases [12, 13] and has been used in many studies to examine the influence of comorbidity on a variety of outcomes, including HCC [14]. In calculating CCI, we excluded etiology of HCC, liver decompensation features and metastasis codes from the original formula as they were used as separate variables in the analysis.

Treatment provided during each admission was identified using ICD-9 codes for the procedures. For patients in the UHC database that had multiple admissions during which different procedures were performed, each patient was assigned to a mutually exclusive treatment category representing the most invasive form of treatment in which liver transplant is the most invasive treatment, followed by resection, RFA, and TACE respectively. Patients without codes for any of the aforementioned procedures were labeled as noninvasive therapy.

Statistical Analysis

We examined the distribution of the aforementioned factors across gender using chi-square tests to identify possible candidates for the multivariate analyses. Then we performed a series of multivariate analyses to examine the possible predictors of the following outcomes.

Metastatic HCC

We classified patients into two groups based on the presence of any metastatic site. We used a binary logistic regression analysis to predict metastatic HCC including all the possible predictors (except treatment options). Backward step-wise selection technique was employed to define the final model keeping only the statistically significant and clinically relevant predictors.

Liver Decompensation

We classified patients into two groups based on the presence of any feature of liver decompensation. We used a binary logistic regression analysis to predict having liver decompensation employing the same technique described above.

Treatment Options

We used a multinomial regression analysis to predict the treatment options using noninvasive as a reference group. The technique described above was used to select the final model.

Inpatient Mortality

We used a binary logistic model to predict inpatient mortality using demographic predictors, liver decompensation features, metastasis, and treatment options employing the same technique in selecting the final model.

Data was analyzed by using the using SAS software, version 9.2 for Windows (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) licensed to Tulane University. This study was approved by the Biomedical Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Tulane University, New Orleans, Louisiana. The NIS is publicly available and contains no personal identifying information and UHC data also lacks any personal identification; therefore, this study was deemed to be exempt from Institutional Review Board approval at our institution.

Results

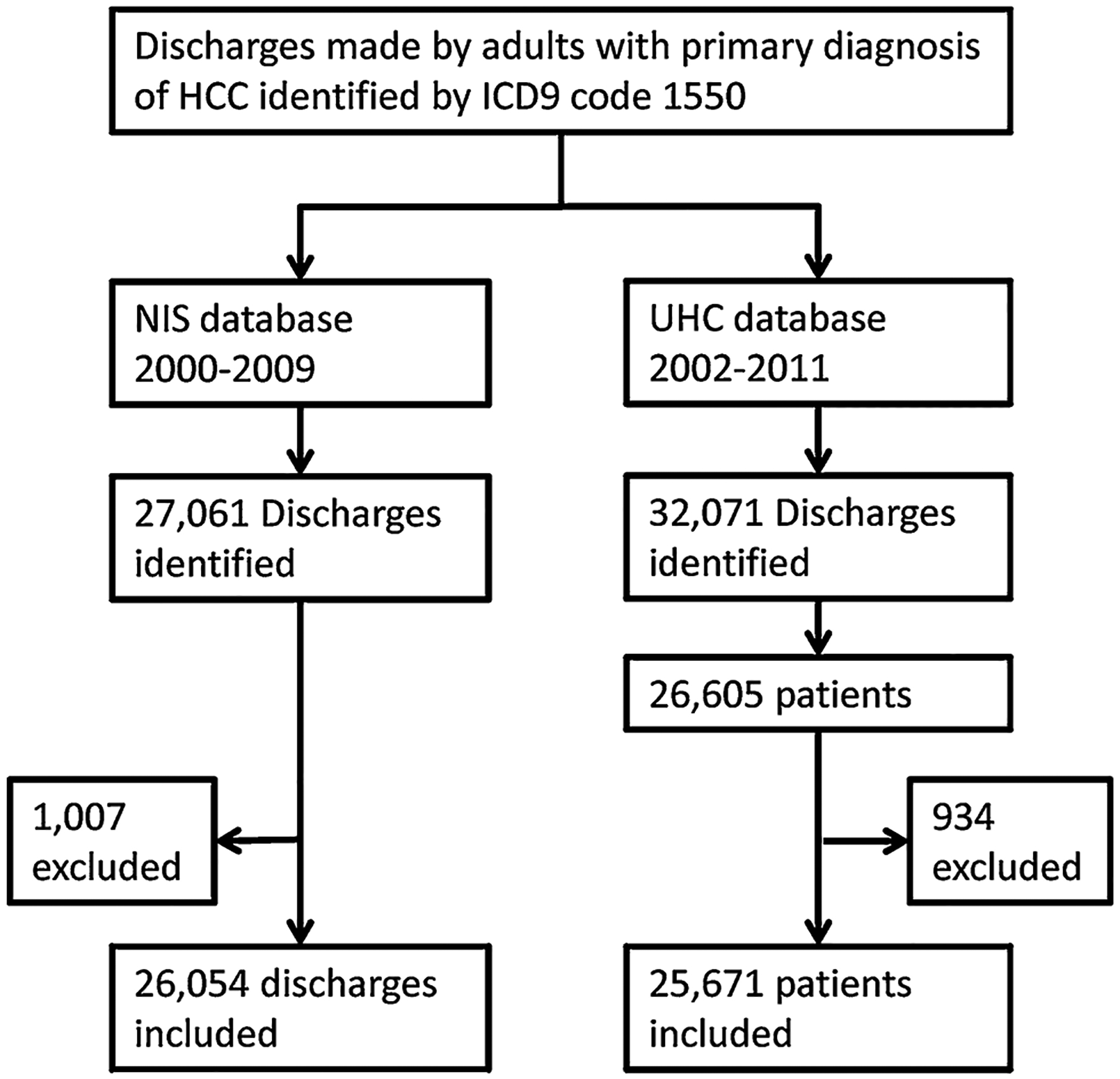

We included 26,054 HCC discharges from the NIS database and 25,671 HCC patients from the UHC database (Fig. 1). The two datasets averaged 73 % male subjects with a mean age of 62 years. The majority of patients were Caucasians (48 %) followed by AA (14 %), Asians (11 %) and Hispanics (11 %). Sixteen percent had other or unknown racial grouping. Medicare was the major primary payer for 41 % of the patients, followed by private insurance (32 %) and Medicaid (17 %). Thirty-eight percent of patients had HCV coded as a risk factor for HCC, 15 % had alcohol abuse, 12 % had HBV, and 49 % had cirrhosis (Table 1). Subjects were allowed to have more than one code; therefore, percentage totals are greater than 100 %.

Fig. 1.

Population inclusion and data processing procedures

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical parameters in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) from two United States (US) databases

| Characteristics | NIS (N = 26,054) |

UHC (N = 25,671) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Age (years) | ||||

| ≤64 | 13,864 | 53 | 16,200 | 63 |

| 65–79 | 9,416 | 36 | 8,143 | 32 |

| ≥80 | 2,774 | 11 | 1,328 | 5 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 18,728 | 72 | 18,895 | 74 |

| Female | 7,300 | 28 | 6,776 | 26 |

| Race | ||||

| Caucasians | 11,147 | 43 | 13,737 | 54 |

| African-American | 3,002 | 12 | 4,101 | 16 |

| Hispanic | 3,267 | 13 | 2,425 | 9 |

| Asians | 2,723 | 10 | 2,829 | 11 |

| Others/unknown | 5,914 | 23 | 2,579 | 10 |

| Primary payer | ||||

| Medicare | 11,460 | 44 | 9,529 | 37 |

| Medicaid | 4,136 | 16 | 4,643 | 18 |

| Private insurance | 7,925 | 31 | 8,487 | 33 |

| Self-pay | 1,272 | 5 | 955 | 4 |

| No charges | 156 | 1 | 331 | 1 |

| Others/unknown | 1,034 | 4 | 1,726 | 7 |

| Geographic region | ||||

| West | 6,739 | 26 | 5,783 | 23 |

| South | 9,077 | 35 | 6,726 | 26 |

| Northeast | 5,897 | 23 | 7,039 | 27 |

| Midwest | 4,341 | 17 | 6,123 | 24 |

| Discharge calendar year | ||||

| 2000 | 1,931 | 7 | NA | NA |

| 2001 | 2,072 | 8 | NA | NA |

| 2002 | 2,203 | 8 | 533 | 2 |

| 2003 | 2,626 | 10 | 2,120 | 8 |

| 2004 | 2,714 | 10 | 2,297 | 9 |

| 2005 | 2,684 | 10 | 2,589 | 10 |

| 2006 | 2,390 | 9 | 2,691 | 10 |

| 2007 | 2,835 | 11 | 3,110 | 12 |

| 2008 | 3,447 | 13 | 3,298 | 13 |

| 2009 | 3,152 | 12 | 3,558 | 14 |

| 2010 | NA | NA | 3,685 | 14 |

| 2011 | NA | NA | 1,790 | 7 |

| Hepatitis C | 8,096 | 31 | 11,381 | 44 |

| Alcohol abuse | 3,356 | 13 | 4,543 | 18 |

| Hepatitis B | 2,666 | 10 | 3,722 | 14 |

| Liver cirrhosis | 11,048 | 42 | 14,289 | 56 |

| Liver decompensation features | ||||

| None | 15,126 | 58 | 14,362 | 56 |

| One | 6,561 | 25 | 5,883 | 23 |

| Two | 2,941 | 11 | 3,240 | 13 |

| ≥Three | 1,426 | 5 | 2,186 | 9 |

| Metastasis | ||||

| None | 21,109 | 81 | 21,235 | 83 |

| Single site | 4,139 | 16 | 3,591 | 14 |

| ≥Two sites | 806 | 3 | 845 | 3 |

| Charlson comorbidity index (score) | ||||

| No comorbidity (0) | 14,405 | 55 | 13,498 | 53 |

| Mild comorbidity (1) | 7,469 | 29 | 7557 | 29 |

| Moderate comorbidity (2) | 2,534 | 10 | 2,550 | 10 |

| Severe comorbidity (≥ 3) | 1,646 | 6 | 2,066 | 8 |

| Treatment options | ||||

| Transplant | 690 | 3 | 2,939 | 11 |

| Resection | 2,623 | 10 | 5,309 | 21 |

| Ablation | 1,853 | 7 | 2,893 | 11 |

| TACE | 2,557 | 10 | 3,142 | 12 |

| Non invasive treatment | 18,331 | 70 | 11,388 | 44 |

| Died during hospitalization | ||||

| No | 21,971 | 84 | 23,279 | 91 |

| Yes | 4,062 | 16 | 2,392 | 9 |

NIS nationwide inpatient sample, UHC university health consortium, NA not available, TACE transarterial chemoembolization

On univariate analysis, across both datasets, 65 % of women had no feature of liver decompensation compared to 54 % of men (<0.001). Metastatic HCC rates were consistent across gender for both datasets, with 15 % of patients having a single site while 3 % had multiple sites of metastases. Overall invasive treatment rates were much higher in UHC compared to NIS databases. Seventy percent of discharges had no invasive treatment codes in NIS compared to only 43 % patients in UHC (p < 0.001). Treatment allocation across genders showed disparities mainly in resection rates which were higher in women (12 % of NIS women received resection compared to 9 % of men and 27 % of UHC women compared to 18 % of UHC men, p < 0.001). The gender disparity appeared to a lesser extent in transplant rates, which were higher in men (2 % of NIS women received liver transplant compared to 3 % of men, and 10 % of UHC women compared to 12 % of UHC men; p < 0.001). With respect to inpatient mortality, women had lower rates (14 % NIS and 8 % UHC women) compared to men (16 % NIS and 10 % UHC men, p < 0.001), but across both genders, a higher percentage of admissions in NIS ended with death (16 %) compared to UHC (9 %, p < 0.001) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Univariate analysis of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients in two United States (US) databases by gender

| Dataset | Men | Women | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| NIS | |||||

| Liver decompensation features | |||||

| None | 10,373 | 55 | 4,728 | 65 | <0.001 |

| One | 4,941 | 26 | 1,619 | 22 | |

| Two | 2,267 | 12 | 674 | 9 | |

| ≥Three | 1,147 | 6 | 279 | 4 | |

| Metastasis | |||||

| None | 15,124 | 81 | 5,959 | 82 | 0.27 |

| Single site | 3,015 | 16 | 1,124 | 15 | |

| ≥Two sites | 589 | 3 | 217 | 3 | |

| Treatment options | |||||

| Transplant | 508 | 3 | 181 | 2 | <0.001 |

| Resection | 1,711 | 9 | 907 | 12 | |

| Ablation | 1,301 | 7 | 547 | 7 | |

| TACE | 1,889 | 10 | 662 | 9 | |

| Non invasive treatment | 13,319 | 71 | 5,003 | 69 | |

| Inpatient death | |||||

| No | 15,644 | 84 | 6,302 | 86 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 3,068 | 16 | 993 | 14 | |

| UHC | |||||

| Liver decompensation features | |||||

| Non | 10,016 | 53 | 4,346 | 64 | <0.001 |

| One | 4,541 | 24 | 1,342 | 20 | |

| Two | 2,564 | 14 | 676 | 10 | |

| ≥Three | 1,774 | 9 | 412 | 6 | |

| Metastasis | |||||

| Non | 15,650 | 83 | 5,585 | 83 | 0.75 |

| Single site | 2,626 | 14 | 965 | 14 | |

| ≥Two sites | 619 | 3 | 226 | 3 | |

| Treatment options | |||||

| Transplant | 2,261 | 12 | 678 | 10 | <0.001 |

| Resection | 3,495 | 18 | 1,814 | 27 | |

| Ablation | 2,110 | 11 | 783 | 12 | |

| TACE | 2,371 | 13 | 771 | 11 | |

| Non invasive treatment | 8,658 | 46 | 2,730 | 40 | |

| Inpatient death | |||||

| No | 17,044 | 90 | 6,235 | 92 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 1,851 | 10 | 541 | 8 | |

NIS nationwide inpatient sample, UHC university health consortium, TACE transarterial chemoembolization

In multivariate analysis, women presented with a lesser degree liver decompensation compared to men (OR 0.79, p < 0.001 for both NIS and UHC). With regard to treatment options, women were more likely to receive resection than their male counterparts (OR 1.34, p < 0.001 for NIS and OR 1.44, p < 0.001 for UHC). All the other gender-based disparities observed in the univariate analysis lost their statistical significance in the multivariate analysis (Table 3). We then stratified chance of receiving resection across gender by degrees of liver decompensation as defined above. We found that women with no features of liver decompensation had higher rates of resection compared to their male counterparts (17 vs. 13 % in NIS and 36 vs. 27 % in UHC for women and men, respectively). Among all patients with features of liver decompensation, resection rates were, as expected, lower compared with those without; furthermore, there was no clear gender disparity (Table 4). We performed a per-year analysis to identify if changing HCC treatment patterns over the last decade have affected the observed gender disparity in resection rates. Although there has been an increase in the rates of resection in the last decade, gender disparity was persistent over all the investigated years (Appendix).

Table 3.

Results of multivariate analysis hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients in two United States (US) databases

| Outcome | Gender | NIS (26,054 discharges) | UHC (25,671 patients) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | p value | 95 % CI | OR | p value | 95 % CI | ||

| Liver decompensation | Male | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Female | 0.79 | <0.001 | 0.75–0.84 | 0.79 | <0.001 | 0.75–0.84 | |

| Receiving liver resection | Male | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Female | 1.34 | <0.001 | 1.22–1.47 | 1.44 | <0.001 | 1.33–1.56 | |

| In-hospital mortality | Male | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Female | 0.85 | <0.001 | 0.78–0.92 | 0.95 | 0.33 | 0.85–1.05 | |

NIS nationwide inpatient sample, UHC university health consortium

Table 4.

Stratification of resection rates by gender in two United States (US) databases

| Data source | Liver decompensation features | Gender | Resection | All other treatments | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | ||||

| NIS | None | Male | 1,386 | 13 | 8,987 | 87 | <0.001 |

| Female | 801 | 17 | 3,927 | 83 | |||

| One | Male | 253 | 5 | 4,688 | 95 | 0.852 | |

| Female | 81 | 5 | 1,538 | 95 | |||

| Two | Male | 61 | 3 | 2,206 | 97 | 0.977 | |

| Female | 18 | 3 | 656 | 97 | |||

| ≥Three | Male | 11 | 1 | 1,136 | 99 | 0.038 | |

| Female | 7 | 3 | 272 | 97 | |||

| UHC | None | Male | 2,741 | 27 | 7,275 | 73 | <0.001 |

| Female | 1,560 | 36 | 2,786 | 64 | |||

| One | Male | 512 | 11 | 4,029 | 89 | 0.019 | |

| Female | 183 | 14 | 1,159 | 86 | |||

| Two | Male | 164 | 6 | 2,400 | 94 | 0.352 | |

| Female | 50 | 7 | 626 | 93 | |||

| ≥Three | Male | 78 | 4 | 1,696 | 96 | 0.538 | |

| Female | 21 | 5 | 391 | 95 | |||

NIS nationwide inpatient sample, UHC university health consortium

Discussion

In our review of two large national databases that captured thousands of HCC cases, we found that females appear to present approximately 20 % more likely with well-compensated liver disease and are 34–44 % more likely to undergo attempted curative HCC resection compared to males with HCC. As a function of increased resection rates, females undergo less locoregional treatment or supportive care-only treatment. Also when other clinical factors are controlled for, women undergo liver transplant as often as men for management of HCC.

The disparity between male and female resection rates in our study appears to derive from different rates of decompensated cirrhosis favoring females. Stratification of the results shows that only when males and females both present with no features of liver decompensation are women more likely to undergo curative resection. Interestingly however, when decompensation severity is controlled for by multivariate analysis, resection is still applied to females more often. This suggests that regardless of severity of decompensation, females are still more likely to receive curative resection than males. It is not clear from our analysis why—if not due to rates of decompensation—females are more likely have their hepatomas resected.

One possible explanation for the disparity in resection rates is that female patients are more likely to present with early stage disease. Although our database did not include specific data on tumor staging other than the presence of metastases (tumor size, tumor number) or tumor location, previous studies have found that female patients present more frequently with early stage tumors [15, 16]. In Dohmen’s and Farinati’s studies, this disparity was primarily attributed to female patients’ stricter adherence to screening protocols. The more favorable stage of tumor presentation has also been attributed to hormonal factors in which development and tumor growth is linked to the presence of androgen and estrogen receptors. However, the exact mechanisms have not yet been elucidated [17].

Another possibility for the disparity in resection rates is that it reflects a disparity in rates of liver transplantation. Previous data have shown that females are less likely to receive liver transplantation than males [18–20]. It has been proposed that the high mathematical weight placed on serum creatinine (Cr) in the MELD formula disadvantages women with relatively low body mass—and associated lower serum Cr—compared to men [19]. This theory suggests women are less able to attain MELD scores as high as men despite being as likely to die of liver disease without transplantation. However, in cases granted an HCC MELD exception, laboratory-calculated MELD does not determine waitlist priority. As a result using UNOS data, Moylan et al. [8] have been shown that the disparity that exists in liver transplantation rates between men and women resolves when examining only those transplanted with HCC. Our results support the findings of Moylan et al. When other clinical features are controlled for, females do not suffer a disparity in transplant rates for HCC. To the contrary, with similar transplantation rates and superior resection rates, women are more likely to receive potentially curative therapy for HCC.

This trend may be unique to the US. Analysis of both smaller Italian (1,352 male and 482 female) and Japanese (487 male and 217 female) HCC databases found no significant difference in treatment of HCC between genders across all treatment modalities, including liver transplant, resection, percutaneous ethanol injection (PEI), TACE, PEI ? TACE, and non-invasive therapies [16, 21]. Females were found to have better survival, a finding attributed to improved HCC screening compliance.

As with any administrative database analysis, this work is susceptible to data entry errors (assigning a wrong ICD9 code) or insufficient code assigning. We expect that these errors would be random and will not affect the direction of associations observed in the analysis. Also, due to the fact that both datasets are nationwide, there might be a possibility of overlapping between the patients and discharges. We do not expect high overlapping as the UHC data is derived from an alliance of not-for-profit academic medical centers [9], while NIS is a sample from all types of hospitals nationwide [10]. Among the included discharges from the NIS, 13 % were from not-forprofit hospitals and only 1 % were from not-for-profit academic hospitals. The latter percentage might represent the overlap between the two datasets. Additionally, due to the fact that the NIS database does not contain unique identifier for the patients, the same patients might be accounting for multiple admissions. We do not expect this significantly affected our results as the rate of readmission was low in the UHC (average admission count per patient was 1.2 with 90 % of the patients having only one admission).

In conclusion, our review of two large national databases with prospectively collected data reveals interesting aspects of HCC gender disparity. First, women are less likely to present with decompensated liver disease. Furthermore, women are more likely to receive invasive HCC treatment, with significantly higher rates of resection across race and diagnoses. Finally although univariate analyses show that US women have lower unadjusted rates of transplant for HCC, the disparity resolves after controlling for pre-treatment factors. Future work should investigate possible medical and social factors why women may actually be advantaged in aggressive treatment of primary liver cancer.

Appendix

Table 5.

Multinomial regression analysis predicting receiving resection versus non-invasive using nationwide inpatient sample (NIS) database

| Variable | Total | % | OR | LCI | UCI | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||||

| <64 | 13,789 | 53 | ||||

| 64–80 | 9,398 | 36 | 1.03 | 0.91 | 1.16 | 0.62 |

| >80 | 2,769 | 11 | 0.37 | 0.31 | 0.45 | <0.001 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 18,669 | 72 | ||||

| Female | 7,287 | 28 | 1.34 | 1.22 | 1.47 | <0.001 |

| Race | ||||||

| Caucasians | 11,121 | 43 | ||||

| African-American | 2,981 | 11 | 0.53 | 0.45 | 0.63 | <0.001 |

| Hispanic | 3,254 | 13 | 0.55 | 0.47 | 0.65 | <0.001 |

| Asians | 2,721 | 10 | 1.32 | 1.15 | 1.51 | <0.001 |

| Others/unknown | 5,879 | 23 | 0.89 | 0.80 | 1.00 | 0.06 |

| Primary payer | ||||||

| Medicare | 11,455 | 44 | ||||

| Medicaid | 4,132 | 16 | 0.56 | 0.47 | 0.66 | <0.001 |

| Private insurance | 7,909 | 30 | 1.26 | 1.11 | 1.42 | <0.001 |

| Self-pay | 1,272 | 5 | 0.46 | 0.35 | 0.60 | <0.001 |

| No charges | 156 | 1 | 0.40 | 0.17 | 0.94 | 0.04 |

| Others/unknown | 1,032 | 4 | 0.49 | 0.37 | 0.66 | <0.001 |

| Region | ||||||

| West | 6,709 | 26 | ||||

| South | 9,024 | 35 | 0.77 | 0.69 | 0.87 | <0.001 |

| Northeast | 5,883 | 23 | 1.05 | 0.93 | 1.19 | 0.43 |

| Midwest | 4,340 | 17 | 0.89 | 0.78 | 1.03 | 0.13 |

| Year | ||||||

| 2000–2005 | 14,161 | 55 | ||||

| 2006–2009 | 11,795 | 45 | 1.62 | 1.49 | 1.77 | <0.001 |

| Charlson comorbidity index (score) | ||||||

| No comorbidity (0) | 14,344 | 55 | ||||

| Mild comorbidity (1) | 7,445 | 29 | 0.93 | 0.84 | 1.02 | 0.13 |

| Moderate comorbidity (2) | 2,526 | 10 | 0.63 | 0.53 | 0.74 | <0.001 |

| Severe comorbidity (≥ 3) | 1,641 | 6 | 0.52 | 0.42 | 0.64 | <0.001 |

| Liver decompensation features | ||||||

| None | 15,067 | 58 | ||||

| One | 6,536 | 25 | 0.28 | 0.25 | 0.31 | <0.001 |

| Two | 2,932 | 11 | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.16 | <0.001 |

| ≥Three | 1,421 | 5 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.09 | <0.001 |

| Metastasis | ||||||

| None | 21,027 | 81 | ||||

| Single site | 4,125 | 16 | 0.34 | 0.29 | 0.39 | <0.001 |

| ≥Two sites | 804 | 3 | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.27 | <0.001 |

Table 6.

Multinomial regression analysis predicting receiving resection versus non-invasive using university health consortium (UHC) database

| Variable | Total | % | OR | LCI | UCI | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||||

| <64 | 14,591 | 62 | ||||

| 64–80 | 7,613 | 32 | 1.18 | 1.07 | 1.31 | <0.001 |

| >80 | 1,281 | 5 | 0.60 | 0.50 | 0.71 | <0.001 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 17,121 | 73 | ||||

| Female | 6,364 | 27 | 1.44 | 1.33 | 1.56 | <0.001 |

| Race | ||||||

| Caucasians | 12,651 | 54 | ||||

| African-American | 3,748 | 16 | 0.52 | 0.47 | 0.59 | <0.001 |

| Hispanic | 2,138 | 9 | 0.54 | 0.46 | 0.63 | <0.001 |

| Asians | 2,646 | 11 | 1.52 | 1.35 | 1.72 | <0.001 |

| Others/unknown | 2,302 | 10 | 0.88 | 0.78 | 1.00 | 0.06 |

| Primary payer | ||||||

| Medicare | 8,846 | 38 | ||||

| Medicaid | 4,080 | 17 | 0.49 | 0.43 | 0.56 | <0.001 |

| Private insurance | 7,845 | 33 | 1.36 | 1.22 | 1.51 | <0.001 |

| Self-pay | 844 | 4 | 0.42 | 0.34 | 0.53 | <0.001 |

| No charges | 295 | 1 | 0.49 | 0.34 | 0.72 | <0.001 |

| Others/unknown | 1,575 | 7 | 0.75 | 0.63 | 0.89 | <0.001 |

| Region | ||||||

| West | 5,218 | 22 | ||||

| South | 6,178 | 26 | 1.27 | 1.14 | 1.42 | <0.001 |

| Northeast | 6,543 | 28 | 1.27 | 1.14 | 1.42 | <0.001 |

| Midwest | 5,546 | 24 | 1.48 | 1.32 | 1.66 | <0.001 |

| Year | ||||||

| 2002–2005 | 7,020 | 30 | ||||

| 2006–2011 | 16,465 | 70 | 1.34 | 1.23 | 1.45 | <0.001 |

| Charlson comorbidity index (score) | ||||||

| No comorbidity (0) | 12,456 | 53 | ||||

| Mild comorbidity (1) | 6,926 | 29 | 0.93 | 0.85 | 1.01 | 0.07 |

| Moderate comorbidity (2) | 2,282 | 10 | 0.90 | 0.79 | 1.02 | 0.09 |

| Severe comorbidity (≥ 3) | 1,821 | 8 | 0.70 | 0.61 | 0.82 | <0.001 |

| Liver decompensation features | ||||||

| None | 14,362 | 56 | ||||

| One | 5,883 | 23 | 0.27 | 0.25 | 0.30 | <0.001 |

| Two | 3,240 | 13 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.15 | <0.001 |

| ≥Three | 2,186 | 9 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.10 | <0.001 |

| Metastasis | ||||||

| None | 19,542 | 83 | ||||

| Single site | 3,183 | 14 | 0.37 | 0.33 | 0.41 | <0.001 |

| ≥Two sites | 760 | 3 | 0.19 | 0.14 | 0.24 | <0.001 |

Fig. 2.

Resection rate by sex and discharge year

Footnotes

Conflict of interest None.

Contributor Information

Stephanie Cauble, Department of Medicine, Section of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Tulane University Health Sciences Center, New Orleans, LA, USA; 5131 O Donovan Drive, 4th Floor Subspecialty Clinic, Baton Rouge, LA 70806, USA.

Ali Abbas, Department of Medicine, Section of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Tulane University Health Sciences Center, New Orleans, LA, USA; Department of Medicine, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA.

Luis Balart, Department of Medicine, Section of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Tulane University Health Sciences Center, New Orleans, LA, USA.

Lydia Bazzano, Department of Epidemiology, Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine, New Orleans, LA, USA.

Sabeen Medvedev, Department of Medicine, George Washington University Medical Center, Washington, DC, USA.

Nathan Shores, Department of Medicine, Section of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Tulane University Health Sciences Center, New Orleans, LA, USA.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2893–2917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.El-Serag HB. Hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2011; 365:1118–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fattovich G, Stroffolini T, Zagni I, Donato F. Hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis: Incidence and risk factors. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:S35–S50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Lope CR, Tremosini S, Forner A, Reig M, Bruix J. Management of HCC. J Hepatol. 2012;56:S75–S87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bruix J, Sherman M. Practice guidelines committee AeAftSoLD: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2005;42: 1208–1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruix J, Sherman M. Diseases AAftSoL: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: An update. Hepatology. 2011;53:1020–1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forner A, Reig ME, de Lope CR, Bruix J. Current strategy for staging and treatment: The BCLC update and future prospects. Semin Liver Dis. 2010;30:61–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moylan CA, Brady CW, Johnson JL, Smith AD, Tuttle-Newhall JE, Muir AJ. Disparities in liver transplantation before and after introduction of the MELD score. JAMA. 2008;300:2371–2378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.University Health Consortium, (HCUP) HCaUP: National inpatient sample. http://www.uhc.edu. Accessed 5 September 2011.

- 10.Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) HCaUP. National Inpatient Sample. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jsp. Accessed 4 September 2011.

- 11.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40: 373–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:613–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shavers VL, Harlan LC, Stevens JL. Racial/ethnic variation in clinical presentation, treatment, and survival among breast cancer patients under age 35. Cancer. 2003;97:134–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simons JP, Ng SC, Hill JS, Shah SA, Zhou Z, Tseng JF. In-hospital mortality from liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma: A simple risk score. Cancer. 2010;116:1733–1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singal AG, Chan V, Getachew Y, Guerrero R, Reisch JS, Cuthbert JA. Predictors of liver transplant eligibility for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in a safety net hospital. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:580–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dohmen K, Shigematsu H, Irie K, Ishibashi H. Longer survival in female than male with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;18:267–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kalra M, Mayes J, Assefa S, Kaul AK, Kaul R. Role of sex steroid receptors in pathobiology of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:5945–5961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mindikoglu AL, Regev A, Seliger SL, Magder LS. Gender disparity in liver transplant waiting-list mortality: The importance of kidney function. Liver Transpl. 2010;16:1147–1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cholongitas E, Marelli L, Kerry A, et al. Female liver transplant recipients with the same GFR as male recipients have lower MELD scores—a systematic bias. Am J Transplant. 2007;7: 685–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Myers RP, Shaheen AA, Aspinall AI, Quinn RR, Burak KW. Gender, renal function, and outcomes on the liver transplant waiting list: Assessment of revised MELD including estimated glomerular filtration rate. J Hepatol. 2011;54:462–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farinati F, Sergio A, Giacomin A, et al. Is female sex a significant favorable prognostic factor in hepatocellular carcinoma? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;21:1212–1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]