Abstract

Lithium argyrodite Li6PS5Cl powders are synthesized from Li2S, P2S5, and LiCl via wet milling and post-annealing at 500°C for 4 h. Organic solvents such as hexane, heptane, toluene, and xylene are used during the wet milling process. The phase evolution, powder morphology, and electrochemical properties of the wet-milled Li6PS5Cl powders and electrolytes are studied. Compared to dry milling, the processing time is significantly reduced via wet milling. The nature of the solvent does not affect the ionic conductivity significantly; however, the electronic conductivity changes noticeably. The study indicates that xylene and toluene can be used for the wet milling to synthesize Li6PS5Cl electrolyte powder with low electronic and comparable ionic conductivities. The all-solid-state cell with the xylene-processed Li6PS5Cl electrolyte exhibits the highest discharge capacity of 192.4 mAh·g−1 and a Coulombic efficiency of 81.3% for the first discharge cycle.

Keywords: all-solid-state battery, lithium argyrodite, milling, conductivity, discharge capacity

Introduction

Inorganic solid electrolytes-based all-solid-state lithium-ion batteries (ASSLIBs), are expected to replace liquid electrolytes-based conventional lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) owing to their advantages, such as safety, higher energy density, and wider operation temperature range (Gao et al., 2018; Lee et al., 2019; Yu et al., 2021). Inorganic solid electrolytes are typically categorized into two groups: sulfide-based and oxide-based. Presently, the sulfides outperform oxides due to higher conductivity and facile manufacturing. A cold-pressed sulfide electrolyte has higher ionic conductivity than an oxide electrolyte sintered at high temperatures (Yu et al., 2018; Huang et al., 2021). Although sulfide-based electrolytes suffer from air instability, releasing toxic hydrogen sulfide (H2S) gas, their tolerance to moisture (hydrolysis resistance) is rapidly improving (Chen et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2020).

Sulfide-based solid electrolytes such as lithium argyrodite (Li6PS5Cl) are typically prepared by mechanical milling and subsequent annealing processes. The precursor materials (Li2S, P2S5, and LiCl) are dry-milled in a high-speed planetary ball mill, and the obtained powder mixture is annealed in a vacuum furnace or in an Ar-filled ampule to obtain a crystalline argyrodite phase. The lithium argyrodite electrolytes prepared via the aforementioned process exhibit a room temperature (25°C) ionic conductivity exceeding 10–3 S·cm−1 (Boulineau et al., 2012; Yu et al., 2016; Yu et al., 2017). However, the dry ball milling process is long and tedious (Boulineau et al., 2013; Yu et al., 2017; Strauss et al., 2020). Additionally, the precursors adhere to the milling jar wall or grinding media (normally, zirconia balls) because of their sticky nature, which can cause compositional and morphological inhomogeneity in the precursor powder mixture prior to the post-annealing process (Wang et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2021).

In wet ball milling, the precursors are mixed in non-dissolving organic solvents. Wet ball milling offer advantages over dry ball milling in terms of improved homogeneity, shortened duration, and scalability (Zhang et al., 2010). However, to the best of our knowledge, wet ball milling and post-annealing processes have not been employed extensively for the synthesis of sulfide-based electrolytes. This is probably due to insufficient understanding of the interaction between the precursors and solvents, and due to a cumbersome energy-intensive solvent evaporation step.

In this study, Li6PS5Cl solid electrolyte powders were synthesized via wet ball milling and post-annealing. Various non-polar organic solvents, such as hexane, heptane, toluene, and xylene, were employed as a liquid medium for high-energy planetary ball milling. The effect of the liquid medium on the phase evolution and powder morphology during the wet milling and post-annealing was investigated. In addition, the influence of solvents on the ionic and electronic conductivities of the Li6PS5Cl solid electrolyte pellets is also discussed.

Materials and Methods

A stoichiometric amount of Li2S (99%, Sigma Aldrich), P2S5 (99%, Sigma Aldrich), and LiCl (98+%, Alfa Aesar) powders were mixed in a planetary ball mill (Pulverisette 6, Fritsch, Germany) using organic solvents such as hexane (96.0+%, deoxidized, Wako, Japan), heptane (99.0+%, super dehydrated, Wako, Japan), toluene (99.5+%, deoxidized, Wako, Japan), and xylene (super dehydrated, Wako). Typically, the milling was performed using 2 g of the powder mixture with zirconia balls (d = 5 mm) in a zirconia jar (80 ml) at a rotational speed of 500 rpm for a duration of 2 h. The slurry was vacuum dried at 150°C for 6 h followed by annealing at 550°C in a tube furnace for 4 h under an argon atmosphere. Argon flow rate was 50 sccm. For comparison, Li6PS5Cl powder was also synthesized via a dry ball milling process, details of which have been reported elsewhere (Park et al., 2021).

The phase analysis of the synthesized powder samples was performed using X-ray diffraction (XRD) (RU-200B, Rigaku Co. Ltd., Japan) with Ni-filtered Cu-Kα radiation. Surface chemical analysis was conducted via the X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) (5400 ESCA, Perkin-Elmer, United States) using a Mg Kα (1,253.6 eV) excitation source. The carbon and hydrogen contents of the Li6PS5Cl powder were determined using an elemental analyzer (EA, Thermo EA1112, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The microstructures were examined via field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM) (JSM-6700F, JEOL, Japan).

The conductivities (ionic and electronic) were measured via electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) (SP-300, Biologic, France) over a frequency range of 0.01 Hz–1 MHz at 30, 40, 60, 80, 100, and 120°C. The Li6PS5Cl powder (55 mg) was placed in a zirconia mold (10 mm) equipped with two stainless-steel rods (d = 10 mm) and cold-pressed at 300 MPa to prepare a disk-shaped pellet sample (diameter = 10 mm, thickness ∼0.5 mm). The relative densities of the pellet samples were estimated to be approximately 92%, calculated from the bulk density of the electrolyte pellet sample and the theoretical density of Li6PS5Cl (1.64 g·cm−3) (Zhou et al., 2019).

The alternating current (AC) impedance spectra were obtained from the electrolyte pellet samples with two stainless-steel (SS) rods acting as current collectors under open-circuit conditions with an excitation potential of 20 mV. The total conductivity, σionic+electronic, was calculated using the equation σionic = t/RA, where R is the total resistance, t is the thickness, and A is the area of the pellet sample, respectively. The ionic conductivities were determined by subtracting the electronic conductivities by DC polarization technique from the total conductivities.

The electronic conductivity was measured via direct current (DC) polarization technique (Boulineau et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2020; Vadhva et al., 2021). The Ni/Li6PS5Cl/Ni symmetrical cells were prepared in a similar way as previously mentioned. Three voltages (0.25, 0.5, and 0.75 V) were applied to the Ni/Li6PS5Cl/Ni symmetrical cells for 2 h, and the resulting current signal was recorded. The resistances were determined from the V-I curves, and the electronic conductivity, σelectronic, was calculated from the thickness and area of the Li6PS5Cl electrolyte pellet sample.

All-solid-state cells (ASSCs) of LiNi0.8Co0.1Mn0.1O2 (NCM)/Li6PS5Cl/super P|Li6PS5Cl|Li-In were assembled by cold pressing at 300 MPa using a zirconia mold (d = 10 mm) equipped with stainless-steel rods. The ratio of NCM:Li6PS5Cl:super P was 70:29:1 by weight. The cathode loading of NCM was 26.8 mg·cm−2. Wet-milled and dry-milled Li6PS5Cl powders were used as the solid electrolyte and the composite cathode, respectively to exclude the solvent effect on reactions at the cathode/solid electrolyte interface. The charge–discharge behavior of the ASSCs was studied at 80°C using a battery test system (SP-300, Biologic, France) with a cutoff voltage of 1.9–3.6 V (vs Li–In). The current density was set to 0.535 mA cm−2. Charging and discharging were carried out in constant current (CC)–constant voltage and CC modes, respectively.

Results and Discussion

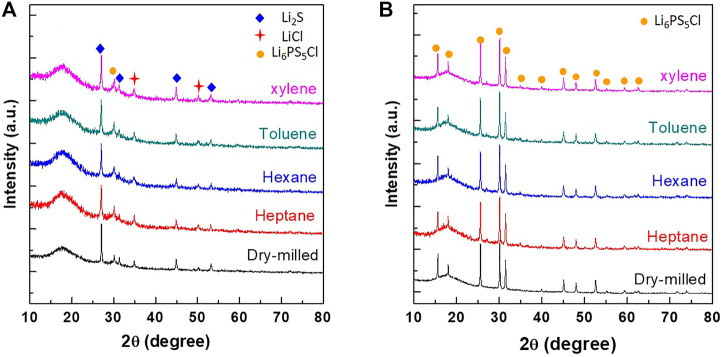

Figure 1 shows the XRD patterns of Li2S, P2S5, and LiCl powder mixtures obtained after milling (dry and wet) and annealing. For the as-milled powder mixture samples (Figure 1A), characteristic peaks of Li2S and LiCl crystalline phases were observed in all the samples, whereas no peaks corresponding to the P2S5 phase were observed. During the milling process, P2S5 and Li2S formed a Li2S-P2S5 amorphous phase (Hayashi et al., 2001) as suggested by the presence of a halo pattern in the range of 15–20°. Another interesting feature observed was the presence of a peak at 30°, corresponding to Li6PS5Cl phase, suggesting its mechanochemical synthesis during ball milling [(Boulineau et al., 2012), (Yubuchi et al., 2018)]. This mechanochemical synthesis effect was observed in both dry- and wet-milled powder samples.

FIGURE 1.

XRD patterns of dry- and wet-milled (hexane, heptane, toluene, and xylene) powder samples (A) before and (B) after post-annealing at 550°C for 4 h.

In the XRD patterns of the post-annealed powder samples (Figure 1B), the peaks of the Li2S and LiCl phases disappeared and the peaks corresponding to the Li6PS5Cl phase appeared. There was no significant difference between the XRD patterns of the wet-milled and dry-milled Li6PS5Cl powder samples. Notably, the total synthesis (milling and post-annealing) time in the case of wet-milled and dry-milled samples was 6 and 16 h, respectively. Considering the highly reduced synthesis time to achieve the same composition, it was concluded that wet ball milling is an efficient method to synthesize Li6PS5Cl powder.

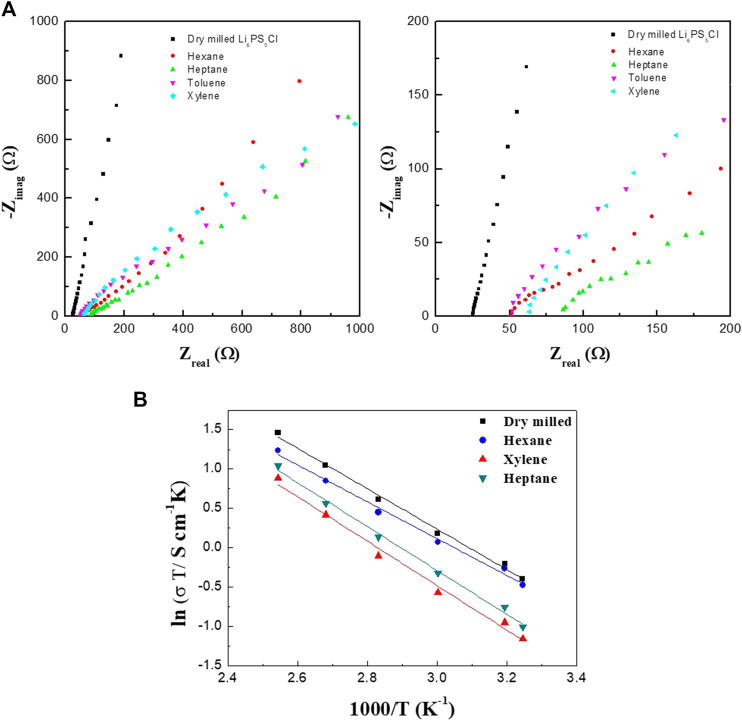

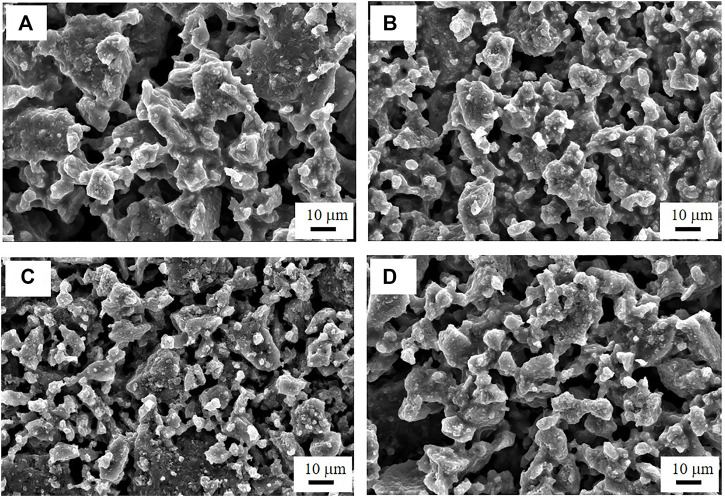

Figures 2A,B show the AC impedance spectra of the SS/Li6PS5Cl/SS symmetrical cells measured at 25°C. In all the spectra, only the spike (straight line) of the blocking electrodes was observed. The ionic conductivity at room temperature can be derived from the total resistance, which is determined from the intersection of the spike with the real axis (Zreal) at the lower frequency side. The ionic conductivities of the Li6PS5Cl electrolyte samples are listed in Table 1. Regardless of the nature of solvent used for the wet milling, the conductivities of the wet-milled Li6PS5Cl electrolyte pellet samples were estimated to be in the range of 1.0–1.9 mS·cm−1. This indicates that the organic solvent does not affect the lithium-ion conduction in the wet-milled Li6PS5Cl. By contrast, the ionic conductivity of the dry-milled Li6PS5Cl electrolyte pellet sample was found to be 2.39 mS·cm−1, which is slightly higher than that of the wet-milled samples. The observed conductivity reduction in the wet-milled Li6PS5Cl electrolyte samples could be associated with the particle size (Choi et al., 2019). Yu et al. also have addressed that the grain boundary resistance was reduced in the argyrodite (Li6PS5Br) electrolyte with large crystallites (Yu et al., 2017). As can be seen in Figure 3, the particles of the wet-milled Li6PS5Cl powder samples were smaller than those of the dry-milled Li6PS5Cl powder sample. The apparent small semicircles observed in the low-frequency region of the impedance spectra of the wet-milled Li6PS5Cl electrolyte samples (hexane and heptane) were due to the grain boundary resistance.

FIGURE 2.

Electrochemical impedance spectra (A) and Arrhenius conductivity plot (B) of symmetrical cells with wet-milled Li6PS5Cl electrolytes prepared using hexane, heptane, toluene, and xylene.

TABLE 1.

Ionic conductivities Li6PS5Cl electrolyte pellet samples.

| Wet-milled Li6PS5Cl | Dry-milled Li6PS5Cl | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n-hexane | n-heptane | Toluene | Xylene | ||

| Ionic conductivity, mS·cm−1 | 1.94 | 0.96 | 1.42 | 1.49 | 2.8 |

FIGURE 3.

FE-SEM images of the (A) dry-milled Li6PS5Cl powder sample, and wet-milled Li6PS5Cl powder samples prepared using (B) heptane, (C) toluene, and (D) xylene.

The Arrhenius plots of the ASSCs is shown in Figure 4C. The linear relationship between the reciprocal absolute temperature (1/T) and the logarithm of conductivity (σ) was found and the activation energy can be determined using the equation of σ = Aexp(−Ea/kBT), where σ is the total conductivity, A is the pre-exponential factor, kB is the Boltzmann constant, and T is the absolute temperature. The activation energies are 0.202, 0.240, and 0.245 eV for the hexane, heptane, and xylene-processed Li6PS5Cl electrolytes, respectively. These values are almost same to the dry-milled Li6PS5Cl electrolyte (0.221 eV), indicating that there are no unwanted secondary phases in the wet-milled Li6PS5Cl powder samples, as can be seen in Figure 1.

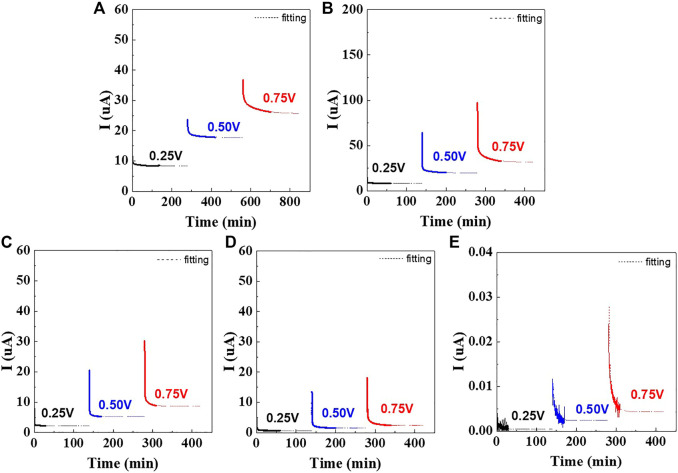

FIGURE 4.

DC polarization curves of symmetrical cells containing wet-milled Li6PS5Cl electrolytes prepared using (A) hexane, (B) heptane, (C) toluene, (D) xylene, and (E) dry-milled Li6PS5Cl electrolyte.

Figure 4 shows the time dependence of the current for Ni/Li6PS5Cl/Ni symmetrical cells in which the Li6PS5Cl powder was prepared using different solvents. When the voltage was applied, the current signal sharply decreased with time and saturated on the order of 10–5 to 10–7 A, depending on the solvent employed during the wet ball milling process. For all cells, the steady state was achieved within 2 h. The currents of the hexane-, toluene-, and xylene-processed Li6PS5Cl samples saturated to ∼10–6 A, whereas for the heptane-processed Li6PS5Cl sample, the current saturated to ∼10–5 A.

The Ni/Li6PS5Cl/Ni symmetrical cells exhibit a linear relationship between voltage and steady-state current values (Supplementary Figure S1). In the steady state, the current is carried only by the electrons because of the blocking electrodes. The resulting electronic conductivities are presented in Table 2. The electronic conductivities of the hexane- and heptane-processed Li6PS5Cl powder samples were calculated to be 2.2 and 2.9 × 10–6 S·cm−1, respectively, which are one order of magnitude higher than those of toluene and xylene-processed Li6PS5Cl samples. The electronic conductivities of the wet-milled Li6PS5Cl samples were three to four orders of magnitude higher than that of the dry-milled Li6PS5Cl sample. It is noteworthy that impurities and defects in the wet-milled Li6PS5Cl powder samples can have a negative effect on their electronic conductivity.

TABLE 2.

Ionic conductivities Li6PS5Cl electrolyte pellet samples.

| Wet-milled Li6PS5Cl | Dry-milled Li6PS5Cl | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n-hexane | n-heptane | toluene | xylene | ||

| Electronic conductivity, S·cm−1 | 1.9 × 10–6 | 3.0 × 10–6 | 6.8 × 10–7 | 2.1 × 10–7 | 4.4 × 10–10 |

To examine the effect of impurities on the electronic conductivity of the Li6PS5Cl electrolyte samples, elemental analysis (carbon and hydrogen content) of the dry- and wet-milled Li6PS5Cl powders was performed and the results are presented in Table 3. A higher amount of carbon was detected in the wet-milled Li6PS5Cl powder samples, which could be attributed to the organic solvents. Due to incomplete evaporation, residual solvent molecules could be deposited on the surface of the wet-milled Li6PS5Cl powder and reduced to pure carbon during the post-annealing process. These carbon particles located at the grain boundaries of the wet-milled Li6PS5Cl electrolytes work as electron transport carriers, which explains the increased electronic conductivity. As can be seen in Table 3, the carbon content was lowest in hexane and highest in xylene. However, no distinct relationship between the electronic conductivity and carbon content could be established. The dry-milled Li6PS5Cl powder sample had the lowest carbon content (0.19%) and exhibited the lowest electronic conductivity of 5.4 × 10–10 S·cm−1.

TABLE 3.

Ionic conductivities Li6PS5Cl electrolyte pellet samples.

| Samples | Wet-milled Li6PS5Cl | Dry-milled Li6PS5Cl | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n-hexane | n-heptane | Toluene | Xylene | ||

| Carbon,wt% | 0,66 | 1.03 | 0,73 | 1.22 | 0,19 |

| Hydrogen,wt% | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.06 |

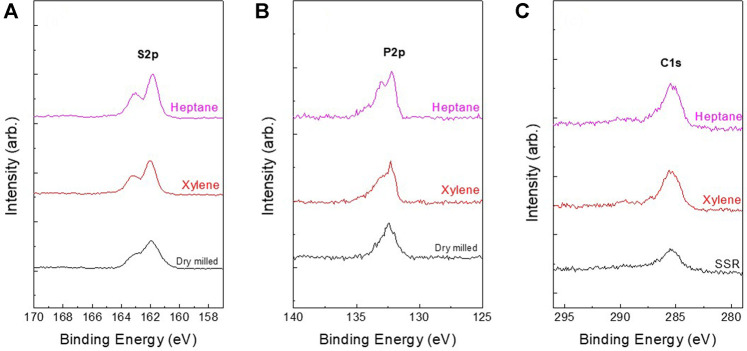

Figure 5 presents the S2p, P2p, C1s and O1s XPS spectra of dry- and wet-milled Li6PS5Cl powder samples. The S2p spectra of the dry-milled Li6PS5Cl powder samples exhibited a doublet with a S2p3/2 component at a binding energy of 162.2 eV, attributed to the PS4 3– tetrahedra (P–S–Li bonds) of argyrodite (Walther et al., 2019; Auvergniot et al., 2017). The peaks attributed to the unreacted Li2S were not detected in the XPS spectra of S1s. Moreover, no sulfur oxides (166–171 eV) or element sulfur (164 eV) were observed (Khallaf et al., 2009). In the P2p spectra, the peak at a binding energy of 132.5 eV was assigned to the PS4 3– tetrahedra of argyrodite (Yubuchi et al., 2018). In addition, the peaks due to P2S5 and P2Sx were not detected in the XPS spectra. This is consistent with the XRD results obtained for the samples (Figure 1). The spectra of dry- and wet-milled Li6PS5Cl powder samples exhibited no significant differences, indicating that wet milling does not have a detrimental effect on the surface composition of the Li6PS5Cl electrolyte. In terms of carbon, the samples exhibited two peaks in the C1s region. The lower binding energy peak (∼286 eV) was attributed to the amorphous carbon species (Takahagi and Ishitani, 1988), whereas the higher binding energy peak (∼290 eV) appeared due to the contamination by carbonate species (Bhattacharya et al., 1997). The carbon content values in Table 3 were consistent with the C1s peak area in Figure 5.

FIGURE 5.

(A) S2p, (B) P2p, and (C) C1s XPS spectra of dry-milled Li6PS5Cl and wet-milled Li6PS5Cl powder samples prepared using hexane and xylene.

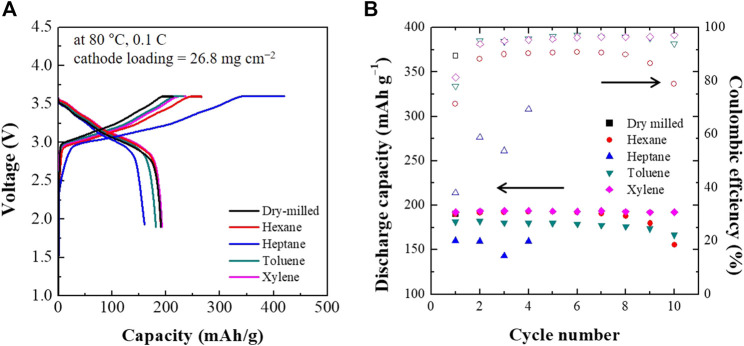

Figure 6 shows the first charge-discharge voltage profiles and cycling performance of the ASSCs composed of dry- and wet-milled Li6PS5Cl electrolytes. The first discharge specific capacities for hexane, heptane, toluene, and xylene were 190, 160, 181, and 192 mAh·g−1, respectively. ASSCs with the xylene and toluene-processed electrolytes processes the first cycle discharge capacity and coulomibic efficiency comparable to the dry-milled sample. When the xylene-processed Li6PS5Cl electrolyte was used, the discharge capacity of the ASSC was found to be stable above 190 mAh·g−1. Although hexane-processed electrolyte exhibited a higher first discharge specific capacity (190 mAh·g−1) than toluene-processed (181 mAh·g−1), the latter exhibited better retention of the rate capacity than hexane. The ASSC with the heptane-processed Li6PS5Cl electrolyte did not maintain its discharge capacity after the fourth cycle.

FIGURE 6.

The first charge-discharge voltage profiles (A) and cycling performance (B) of ASSCs containing dry- and wet-milled Li6PS5Cl electrolytes.

A different trend was observed for the initial Coulombic efficiencies, as is evident in Figure 6. The Coulombic efficiency of the ASSCs increased in the following order: xylene (81.3%) > toluene (78.1%) > hexane (71.4%) > heptane (38.1%). An interesting feature was that this trend was consistent with the electronic conductivity of the wet-milled Li6PS5Cl powder samples. In other words, high electronic conductivity can lead to a reduced Coulombic efficiency. The ASSCs with xylene- and toluene-processed Li6PS5Cl electrolytes maintained a Coulombic efficiency of 95–96% during the first 10 cycles. By contrast, the ASSC with the hexane-processed Li6PS5Cl electrolytes exhibited Coulombic efficiencies of 90% which gradually decreased with increasing cycle number. In the case of heptane, the ASSC exhibited much lower Coulombic efficiencies than the other ASSCs. The capacity and Coulombic efficiency retention might be closely related to the electronic conductivity of the Li6PS5Cl electrolyte. The Li6PS5Cl electrolyte powders prepared using xylene and toluene exhibited relatively low electronic conductivity on the order of 10–7 S·cm−1, resulting in high discharge capacity and Coulombic efficiency retention after 10 cycles, whereas those prepared using hexane and heptane, exhibited higher electronic conductivities, lower discharge capacity and decaying Coulombic efficiency with cycling.

Conclusion

A single-phase Li6PS5Cl powder was synthesized from Li2S, P2S5, and LiCl powder mixture via wet ball milling with various organic solvents and post-annealing. Compared to dry milling, the processing time was significantly reduced. The ionic conductivities of the wet-milled and post-annealed Li6PS5Cl powder samples were in the range of 1.0–1.9 S·cm−1, which was slightly lower than that of the dry-milled Li6PS5Cl powder sample (2.8 S·cm−1). FE-SEM analyses revealed that the particle size was reduced in the wet-milled Li6PS5Cl powder samples, and the increased grain boundary was responsible for the reduced ionic conductivity. The wet-milled Li6PS5Cl powder samples showed three or four orders of magnitude higher electronic conductivity than that of the dry-milled Li6PS5Cl powder sample. In terms of solvent for wet milling, xylene and toluene were found to be better than hexane and heptane, leading to one order of magnitude lower electronic conductivity. It appears that sulfur deficiency or the state of the residual carbon could be responsible for the observed variation in the electron conductivity. The ASSC with the xylene-processed Li6PS5Cl electrolyte exhibited the highest discharge capacity of 192.4 mAh·g−1 and a Coulombic efficiency of 81.3% for the first discharge cycle. The lower discharge capacity and Coulombic efficiency retention observed in the ASSCs with hexane- and heptane-processed Li6PS5Cl electrolytes was attributed to the increased electronic conductivity of these electrolytes. In the future, the strategies to reduce the electronic conductivity of the wet-milled Li6PS5Cl should be presented in order to use it as an all-solid-state lithium battery electrolyte.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author Contributions

JL and YP contributed to sample preparation and characterization. JL wrote the first draft of the manuscript. JM and HH contributed to conception and design of the study and wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant (NRF-2020M3D1A2102918) and by the Technology Development Program to Solve Climate Changes of the National Research Foundation (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning (No.2017M1A2A2044927).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fchem.2021.778057/full#supplementary-material

References

- Auvergniot J., Cassel A., Ledeuil J.-B., Viallet V., Seznec V., Dedryvère R. (2017). Interface Stability of Argyrodite Li6PS5Cl toward LiCoO2, LiNi1/3Co1/3Mn1/3O2, and LiMn2O4 in Bulk All-Solid-State Batteries. Chem. Mater. 29, 3883–3890. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.6b04990 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya A. K., Pyke D. R., Walker G. S., Werrett C. R. (1997). The Surface Reactivity of Different Aluminas as Revealed by Their XPS C1s Spectra. Appl. Surf. Sci. 108, 465–470. 10.1016/S0169-4332(96)00685-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boulineau S., Courty M., Tarascon J.-M., Viallet V. (2012). Mechanochemical Synthesis of Li-Argyrodite Li6PS5X (X=Cl, Br, I) as Sulfur-Based Solid Electrolytes for All Solid State Batteries Application. Solid State Ionics 221, 1–5. 10.1016/j.ssi.2012.06.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boulineau S., Tarascon J.-M., Leriche J.-B., Viallet V. (2013). Electrochemical Properties of All-Solid-State Lithium Secondary Batteries Using Li-Argyrodite Li6PS5Cl as Solid Electrolyte. Solid State Ionics 242, 45–48. 10.1016/j.ssi.2013.04.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H. M., Maohua C., Adams S. (2015). Stability and Ionic Mobility in Argyrodite-Related Lithium-Ion Solid Electrolytes. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 17, 16494–16506. 10.1039/C5CP01841B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S., Ann J., Do J., Lim S., Park C., Shin D. (2019). Application of Rod-like Li6PS5Cl Directly Synthesized by a Liquid Phase Process to Sheet-type Electrodes for All-Solid-State Lithium Batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 166, A5193–A5200. 10.1149/2.0301903jes [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Z., Sun H., Fu L., Ye F., Zhang Y., Luo W., et al. (2018). Promises, Challenges, and Recent Progress of Inorganic Solid-State Electrolytes for All-Solid-State Lithium Batteries. Adv. Mater. 30, 1705702. 10.1002/adma.201705702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi A., Hama S., Morimoto H., Tatsumisago M., Minami T. (2001). Preparation of Li2S-P2s5 Amorphous Solid Electrolytes by Mechanical Milling. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 84, 477–479. 10.1111/j.1151-2916.2001.tb00685.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X., Su J., Song Z., Xiu T., Jin J., Badding M. E., et al. (2021). Synthesis of Ga-doped Li7La3Zr2O12 Solid Electrolyte with High Li+ Ion Conductivity. Ceramics Int. 47, 2123–2130. 10.1016/j.ceramint.2020.09.047 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khallaf H., Chai G., Lupan O., Chow L., Park S., Schulte A. (2009). Characterization of Gallium-Doped CdS Thin Films Grown by Chemical bath Deposition. Appl. Surf. Sci. 255, 4129–4134. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2008.10.115 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H., Oh P., Kim J., Cha H., Chae S., Lee S., et al. (2019). Advances and Prospects of Sulfide All‐Solid‐State Lithium Batteries via One‐to‐One Comparison with Conventional Liquid Lithium Ion Batteries. Adv. Mater. 31, 1900376. 10.1002/adma.201900376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park Y. S., Lee J. M., Yi E. J., Moon J.-W., Hwang H. (2021). All-solid-state Lithium-Ion Batteries with Oxide/sulfide Composite Electrolytes. Materials 14, 1998. 10.3390/ma14081998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss F., Zinkevich T., Indris S., Brezesinski T. (2020). Li7GeS5Br-An Argyrodite Li-Ion Conductor Prepared by Mechanochemical Synthesis. Inorg. Chem. 59, 12954–12959. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.0c02094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahagi T., Ishitani A. (1988). XPS Study on the Surface Structure of Carbon Fibers Using Chemical Modification and C1s Line Shape Analysis. Carbon 26, 389–395. 10.1016/0008-6223(88)90231-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vadhva P., Hu J., Johnson M. J., Stocker R., Braglia M., Brett D. J. L., et al. (2021). Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy for All‐Solid‐State Batteries: Theory, Methods and Future Outlook. ChemElectroChem 8, 1930–1947. 10.1002/celc.202100108 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walther F., Koerver R., Fuchs T., Ohno S., Sann J., Rohnke M., et al. (2019). Visualization of the Interfacial Decomposition of Composite Cathodes in Argyrodite-Based All-Solid-State Batteries Using Time-Of-Flight Secondary-Ion Mass Spectrometry. Chem. Mater. 31, 3745–3755. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.9b00770 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Jiang Y., Wu J., Jiang Y., Huang S., Zhao B., et al. (2020). Reaction Mechanism of Li2S-P2s5 System in Acetonitrile Based on Wet Chemical Synthesis of Li7P3S11 Solid Electrolyte. Chem. Eng. J. 393, 124706. 10.1016/j.cej.2020.124706 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu C., Ganapathy S., Hageman J., van Eijck L., van Eck E. R. H., Zhang L., et al. (2018). Facile Synthesis toward the Optimal Structure-Conductivity Characteristics of the Argyrodite Li6PS5Cl Solid-State Electrolyte. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 10, 33296–33306. 10.1021/acsami.8b07476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu C., Ganapathy S., van Eck E. R. H., van Eijck L., Basak S., Liu Y., et al. (2017). Revealing the Relation between the Structure, Li-Ion Conductivity and Solid-State Battery Performance of the Argyrodite Li6PS5Br Solid Electrolyte. J. Mater. Chem. A. 5, 21178–21188. 10.1039/C7TA05031C [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu C., van Eijck L., Ganapathy S., Wagemaker M. (2016). Synthesis, Structure and Electrochemical Performance of the Argyrodite Li 6 PS 5 Cl Solid Electrolyte for Li-Ion Solid State Batteries. Electrochimica Acta 215, 93–99. 10.1016/j.electacta.2016.08.081 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu C., Zhao F., Luo J., Zhang L., Sun X. (2021). Recent Development of Lithium Argyrodite Solid-State Electrolytes for Solid-State Batteries: Synthesis, Structure, Stability and Dynamics. Nano Energy 83, 105858. 10.1016/j.nanoen.2021.105858 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yubuchi S., Uematsu M., Deguchi M., Hayashi A., Tatsumisago M. (2018). Lithium-Ion-Conducting Argyrodite-type Li6PS5X (X = Cl, Br, I) Solid Electrolytes Prepared by a Liquid-phase Technique Using Ethanol as a Solvent. ACS Appl. Energ. Mater. 1, 3622–3629. 10.1021/acsaem.8b00280 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D., Cai R., Zhou Y., Shao Z., Liao X.-Z., Ma Z.-F. (2010). Effect of Milling Method and Time on the Properties and Electrochemical Performance of LiFePO4/C Composites Prepared by ball Milling and thermal Treatment. Electrochimica Acta 55, 2653–2661. 10.1016/j.electacta.2009.12.023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Zhang L., Yan X., Wang H., Liu Y., Yu C., et al. (2019). All-in-one Improvement toward Li6PS5Br-Based Solid Electrolytes Triggered by Compositional Tune. J. Power Sourc. 410-411, 162–170. 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2018.11.016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Zhang L., Liu Y., Yan X., Xu B., Wang L., (2020). One-step solution process toward formation of Li6PS5Cl argyrodite solid electrolyte for all-solid-state lithium-ion batteries, J. Alloys and Compounds, 812 152103. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao F., Liang J., Yu C., Sun Q., Li X., Adair K., et al. (2020). A Versatile Sn‐Substituted Argyrodite Sulfide Electrolyte for All‐Solid‐State Li Metal Batteries. Adv. Energ. Mater. 10, 1903422. 10.1002/aenm.201903422 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L., Park K.-H., Sun X., Lalère F., Adermann T., Hartmann P., et al. (2019). Solvent-Engineered Design of Argyrodite Li6PS5X (X = Cl, Br, I) Solid Electrolytes with High Ionic Conductivity. ACS Energ. Lett. 4, 265–270. 10.1021/acsenergylett.8b01997 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.