Abstract

Infective endocarditis (IE) in neonates is associated with high mortality and incidence has been increasing over the past two decades. The majority of very low birth weight infants will be treated with at least one nephrotoxic medication during their hospital course. Over one-quarter of very low birth weight neonates exposed to gentamicin may develop acute kidney injury (AKI); this is particularly worrisome as AKI is an independent factor associated with increased neonatal mortality and increased length of stay. AKI during periods of neonatal nephrogenesis, which continues until 34–36 weeks postmenstrual age, may also have serious effects on the long-term nephron development which subsequently puts infants at risk of chronic kidney disease. Extended interval (EI) aminoglycoside (AMG) dosing has been used for decades in adult populations and has proven to reduce AKI while being at least as effective as traditional dosing, although there is limited published research for using an EI AMG in endocarditis in adults or pediatric patients. We describe an extremely low birth weight neonate, born preterm at 24 weeks gestation treated for Klebsiella pneumoniae IE that required AMG therapy who also had concurrent AKI. We utilized EI AMG combination therapy for treatment of Klebsiella pneumoniae endocarditis with good outcome and encourage others to report their experiences to improve our knowledge of EI AMG in this population.

Keywords: acute kidney injury, aminoglycoside, bacterial endocarditis, extended interval, Klebsiella pneumoniae, tobramycin

Introduction

Infective endocarditis (IE) is associated with high morbidity and mortality. The epidemiology of IE in pediatric patients has changed during the past several decades related to the increased survival rate of children with congenital heart disease,1 the predominant underlying condition for IE in children over the age of 2 years.1,2 The frequency of IE has increased in newborn infants over the past two decades due to advances in invasive techniques and supportive care to manage infants with complex health problems, including heart disease, and infants under the age of one month account for 7.3% of cases.3 Premature infants account for 31% of infant IE deaths.3 Premature infants are likely more susceptible to endocarditis due to higher prevalence of central venous catheters and having immature immune systems. One class of medications used to treat IE in pediatric and adult patients are the AMG class. These agents were historically given thrice daily to work synergistically with beta-lactams for the treatment of IE.

Data over the past few decades on EI AMG dosing collectively suggest potential decreased serum creatinine concentrations and/or less incidence of nephrotoxicity may be achieved while being at least as efficacious as traditional multiple daily dosing.4–13 Minimizing risk for nephrotoxicity is a critical goal in the treatment of IE, particularly for premature neonates who are already more susceptible to AKI and the longer term complication of chronic kidney disease.14–20 EI AMG dosing has been the standard of care for septic neonates for decades.10,21,22 Using EI AMG dosing may be additionally advantageous for IE in this population, although there are limited data to support this practice.

Case Report

Here we present a premature Hispanic male neonate born at gestational age 24 weeks and 4-days-old with a birth weight of 750 grams to a 23-year-old mother via vaginal delivery due to preterm premature rupture of membranes and concern for chorioamnionitis. Patient had poor respiratory effort following delivery and was intubated shortly after birth. Due to the concern for early onset sepsis, a blood culture was obtained and the patient was subsequently started on intravenous (IV) ampicillin and gentamicin. Antibiotics were given for 48 hours and discontinued following negative cultures. At day of life (DOL) 12, he developed clinical signs of sepsis including respiratory decline, acidosis, increased HeRO score23 and unexplained leukocytosis (33,000 k/uL) so the patient was subsequently started on IV nafcillin and gentamicin. A percutaneous blood culture revealed growth of gram-negative bacteria approximately 12 hours after the culture was drawn. A suspected source of infection included the patient's umbilical venous catheter which was removed on DOL 8. Source was unlikely due to urinary tract infection as urine culture was negative. Patient also had no clinical signs of necrotizing enterocolitis or pneumonia by chest radiographs

Identification and susceptibilities came back about 48 hours after the cultures were drawn on DOL 12 (Table 1). Culture grew Klebsiella pneumoniae with wild-type susceptibility pattern (MIC ≤ 1 to tobramycin). Nafcillin and gentamicin were discontinued and IV cefepime was started for improved central nervous system penetration. Pretreated cerebrospinal fluid culture was negative but a repeat blood culture on DOL 13 remained positive, clearing by DOL 15.

Table.

Timeline of Cultures with Bacterial Identification

| Culture | Date | Pathogen |

|---|---|---|

| Percutaneous Blood Draw | DOL 0 | No growth |

| Percutaneous Blood Draw | DOL 12 | Klebsiella pneumoniae |

| Urine, Catheter | DOL 12 | No growth |

| CSF sample | DOL 13 | No growth |

| Percutaneous Blood Draw | DOL 13 | Klebsiella pneumoniae |

| Percutaneous Blood Draw | DOL 15 | No growth |

| Percutaneous Blood Draw | DOL 19 | Coagulase negative Staphylococcus |

| Urine, Catheter | DOL 13 | No growth |

| Percutaneous Blood Draw | DOL 23 | No growth |

DOL, day of life

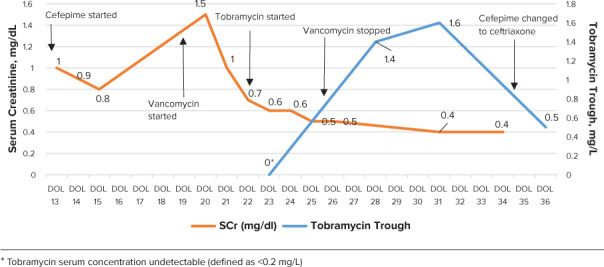

A central line was placed on DOL 16 after 36 hours of sterile cultures due to anticipated prolonged antimicrobial use, initially for presumed meningitis. He then had clinical deterioration with concerns for sepsis on DOL 19 that prompted a repeat sepsis evaluation, resulting in the addition of vancomycin alongside cefepime. Patient was also discovered to have an elevated serum creatinine value of 1.5 mg/dL increased from 0.8 mg/dL five days prior, worsening acidosis, and required increased respiratory support (Figure 1).

Figure.

Renal function, therapeutic concentrations, and antibiotics over course.

On DOL 19, a new heart murmur was appreciated on examination. The echocardiogram on DOL 20 found a fibrinous sheath in the inferior right atrium, raising concerns for endocarditis. Blood culture from DOL 19 grew coagulase-negative staphylococci after 24 hours. Coagulase-negative staphylococci did not grow on repeat culture taken on DOL 23 and therefore was considered to be a possible contaminant not contributing to endocarditis and was treated with 7 days of vancomycin. The Infectious Disease service was then consulted for management of Klebsiella pneumoniae endocarditis. Multiple Infectious Disease providers were involved in his care throughout this hospital course. Treatment with a beta-lactam antibiotic and aminoglycoside for Klebsiella pneumoniae endocarditis was recommended.

EI AMG dosing was decided upon for treatment due to several factors: (1) patient's current episode of AKI when aminoglycoside treatment was being initiated, (2) concurrent treatment of other nephrotoxins (vancomycin), and (3) to optimize pharmacokinetic properties to maximum peak/minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC). Tobramycin or gentamicin 4–5 mg/kg every 24–48 hours is recommended by some neonatal dosing guides, while tobramycin or gentamicin 7.5 mg/kg/day divided three times per day is recommend for the treatment of IE in older pediatric populations.2 Following thoughtful team discussion surrounding the risks and benefits of an antibiotic regimen to treat IE in the setting of AKI, the decision was made to transition to tobramycin. While IE treatment with an AMG has typically been thrice daily in older pediatric patients and evidence may support dosing at 36 hour intervals in premature neonates for other indications, the team opted to treat with 24 hour dosing and close monitoring of cultures, renal function, and therapeutic concentrations. Therefore, given limited data availability, tobramycin 4 mg/kg IV every 24 hours was started on DOL 22. Close pharmacokinetic monitoring was used during tobramycin therapy with a goal peak of 8–10 mcg/ml and trough of <1 mcg/ml was agreed upon. Peak was sub-therapeutic on DOL 23 at 6.5 mg/L and trough was undetectable, so the dose was increased to tobramycin 4.5 mg/kg (and weight adjusted) IV every 24 hours.

A repeat peak serum concentration of 7.7 mg/L was extrapolated to be therapeutic after being collected ~45–60 minutes late. Subsequent trough was 1.4 mg/L on DOL 28 followed by 1.6 mg/L on DOL 32 so the interval was extended out to tobramycin to 4.5 mg/kg IV every 36 hours.

Repeat blood cultures at DOL 23 and at 16 weeks of age were found to be sterile after starting antimicrobial therapy. Once therapeutic concentrations were reached, concentrations were drawn approximately weekly without any further adjustments needed to dose beside weight adjustments. After the initial AKI, serum creatinine continued to downtrend and remained stable throughout admission. Combination therapy was continued for 6 weeks. Repeat echocardiogram at 5 weeks of life showed a fibrinous sheath in the atrium. Echocardiogram at 3 months and 9 months of life was negative for any vegetation or evidence of endocarditis. Patient failed automated auditory brainstem response newborn hearing screen but passed outpatient oto-acoustic emissions hearing test at around 6 months of age. Patient was discharged at 3 months of age with good outcome.

Discussion

There is limited literature available describing EI dosing for endocarditis in pediatric patients, including neonates. In fact, the American Heart Association guidelines recommend thrice daily dosing for pediatric patients, but also specifically address the lack of data for EI AMG dosing in IE. Over the past two decades there has been a plethora of research—including randomized trials—evaluating nephrotoxicity and efficacy showing the advantages of EI over multiple daily AMG regimens,6,8,11,12, notably in cystic fibrosis and primary ciliary dyskinesia patients.7,9,24,25 Preclinical data support efficacy of once daily AMG dosing for Streptococcal endocarditis.26 Historical findings show AKI incidence of 0%–7.5% for EI compared to 14.7–15.4% for multiple daily doses, respectively.11,12

The rationale for using EI in our patient included: patient having current AKI, concomitant nephrotoxic therapy (vancomycin), and the desire to optimize pharmacokinetic properties of AMG (Peak/MIC) ratio. A high priority from the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit team was placed on forestalling the worsening of current AKI and preventing future incidences. Our patient was at very high risk for AKI and chronic kidney disease due to multiple factors including extremely low birth weight, poor clinical course/sepsis, duration of nephrotoxic therapy and concurrent nephrotoxic medications.4,27,28 As expected, exposure to multiple nephrotoxic medications can increase risk of AKI, and approximately one-quarter of very low birth weight infants exposed to gentamicin may develop AKI.29 The team attempted to minimize exposure and use all strategies possible to minimize risk/worsening of AKI.30

This case report adds to the existing data that demonstrate the efficacy of EI compared to multiple daily dosing regimens with AMG. The rationale of using EI AMG dosing for neonates and pediatrics is fourfold: 1) optimizing the bacterial killing activity is positively correlated with high peak concentrations;7 2) the post-antibiotic effect for AMGs is experienced when drug concentrations fall below the pathogen's MIC but can still inhibit bacterial growth;7 3) reduction of adaptive resistance by having a medication-free interval (this is a reversible resistance that can develop shortly after initial exposure but can disappear several hours after no medication is present;7 4) EI is thought to reduce renal tubular accumulation of AMG and would therefore have a lower nephrotoxic potential.31 An additional observed benefit includes reduced access to intravenous lines, as this patient was at higher risk for a central line associated infections.

Conclusion

Although there are limited data supporting EI AMG dosing for endocarditis in neonates, our case report describes a patient who was successfully treated using this method and had follow-up findings suggestive of full clearance of infection. Treating patients with an EI AMG targeting a peak concentration of ≥ 8–10 mg/L and a trough concentration of ≤ 1 mg/L would be reasonable for similar patient cases.

Acknowledgments

Editing and review was completed by Alysa Blakeney before submission.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AKI

acute kidney injury

- AMG

aminoglycoside

- DOL

day of life

- EI

extended interval

- IE

infective endocarditis

- IV

intravenous

- MIC

minimum inhibitory concentration

Footnotes

Disclosures. The authors declare no conflicts or financial interest in any product or service mentioned in the manuscript, including grants, equipment, medications, employment, gifts, and honoraria. The authors had full access to all patient information in this report and take responsibility for the integrity and accuracy of the report.

Ethical Approval and Informed Consent. The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national guidelines on human experimentation and have been approved by the appropriate committees at our institution. However, given the nature of this study, informed consent was not required by our institution.

References

- 1.Ferrieri P, Gewitz MH, Gerber MA et al. Unique features of infective endocarditis in childhood. Circulation . 2002;105(17):2115–2126. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000013073.22415.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baltimore RS, Gewitz M, Baddour LM et al. Infective Endocarditis in Childhood: 2015 Update: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation . 2015;132(15):1487–1515. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Day MD, Gauvreau K, Shulman S, Newburger JW. Characteristics of children hospitalized with infective endocarditis [published correction appears in Circulation. 2010;122:e560] Circulation . 2009;119:865–870. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.798751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanna MH, Askenazi DJ, Selewski DT. Drug-induced acute kidney injury in neonates. Curr Opin Pediatr . 2016;28(2):180–187. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smyth A, Tan KHV, Hyman-Taylor P et al. Once versus three-times daily regimens of tobramycin treatment for pulmonary exacerbations of cystic fibrosis—the TOPIC study: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet . 2005;365(9459):573–578. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17906-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prins JM, Büller HR, Kuijper EJ et al. Once versus thrice daily gentamicin in patients with serious infections. Lancet . 1993;341(8841):335–339. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)90137-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wassil SK, Fox KM, White JW. Once daily dosing of aminoglycosides in pediatric cystic fibrosis patients: a review of the literature. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther . 2008;13(2):68–75. doi: 10.5863/1551-6776-13.2.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Low YS, Tan SL, Wan AS. Extended-interval gentamicin dosing in achieving therapeutic concentrations in malaysian neonates. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther . 2015;20(2):119–127. doi: 10.5863/1551-6776-20.2.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Higgins KL, Noda C, Stultz JS. Extended Interval Tobramycin Pharmacokinetics in a Pediatric Patient With Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia Presenting With an Acute Respiratory Exacerbation. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther . 2018;23(2):159–163. doi: 10.5863/1551-6776-23.2.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pacifici GM. Clinical pharmacokinetics of aminoglyco-sides in the neonate: a review. Eur J Clin Pharmacol . 2009;65(4):419–427. doi: 10.1007/s00228-008-0599-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rybak MJ, Abate BJ, Kang SL et al. Prospective evaluation of the effect of an aminoglycoside dosing regimen on rates of observed nephrotoxicity and ototoxicity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother . 1999;43(7):1549–1555. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.7.1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murry KR, McKinnon PS, Mitrzyk B, Rybak MJ. Pharmacodynamic characterization of nephrotoxicity associated with once-daily aminoglycoside. Pharmacotherapy . 1999;19(11):1252–1260. doi: 10.1592/phco.19.16.1252.30876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Contopoulos-Ioannidis DG, Giotis ND, Baliatsa DV, Ioannidis JP. Extended-interval aminoglycoside administration for children. Pediatrics . 2004;114:e111–e118. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.1.e111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.White SL, Perkovic V, Cass A et al. Is low birth weight an antecedent of CKD in later life? A systematic review of observational studies. AM J Kidney Dis . 2009;54:248–261. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carmody JB, Charlton JR. Short-term gestation, long-term risk: prematurity and chronic kidney disease. Pediatrics . 2013;131:1168–1179. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Askenazi DJ, Feig DI, Graham NM et al. 3–5 year longitudinal follow-up of pediatric patients after acute renal failure. Kidney Int . 2006;69(1):184–189. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mammen C, Al Abbas A, Skippen P et al. Long-term risk of CKD in children surviving episodes of acute kidney injury in the intensive care unit: a prospective cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis . 2012;59(4):523–530. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coca SG, Singanamala S, Parikh CR. Chronic kidney disease after acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Kidney Int . 2012;81(5):442–448. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abitbol CL, Bauer CR, Montané B et al. Long-term follow-up of extremely low birth weight infants with neonatal renal failure. Pediatr Nephrol . 2003;18(9):887–893. doi: 10.1007/s00467-003-1186-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harer MW, Pope CF, Conaway MR, Charlton JR. Follow-up of Acute kidney injury in Neonates during Childhood Years (FANCY): a prospective cohort study. Pediatr Nephrol . 2017;32(6):1067–1076. doi: 10.1007/s00467-017-3603-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agarwal G, Rastogi A, Pyati S et al. Comparison of once-daily versus twice-daily gentamicin dosing regimens in infant ≥2500 g. J Perinatol . 2002;22(4):268–274. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7210704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thureen PJ, Reiter PD, Gresores A et al. Once- versus twice-daily gentamicin dosing in neonates ≥34 weeks's gestation: cost-effectiveness analyses. Pediatrics . 1999;103:594–598. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.3.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fairchild KD, Aschner JL. HeRO monitoring to reduce mortality in NICU patients. Res Rep Neonatol . 2012;2:65–76. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prescott WA, Jr, Nagel JL. Extended-interval once-daily dosing of aminoglycosides in adult and pediatric patients with cystic fibrosis. Pharmacotherapy . 2010;30(1):95–108. doi: 10.1592/phco.30.1.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jenh AM, Tamma PD, Milstone AM. Extended-interval aminoglycoside dosing in pediatrics. Pediatr Infect Dis J . 2011;30(4):338–339. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31820f0f3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gavaldà J, Pahissa A, Almirante B et al. Effect of gentamicin dosing interval on therapy of viridans streptococcal experimental endocarditis with gentamicin plus penicillin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother . 1995;39(9):2098–2103. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.9.2098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Selewski DT, Charlton JR, Jetton JG et al. Neonatal Acute Kidney Injury. Pediatrics . 2015;136(2):e463–e473. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-3819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jetton JG, Boohaker LJ, Sethi SK et al. Incidence and outcomes of neonatal acute kidney injury (AWAKEN): a multicentre, multinational, observational cohort study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health . 2017;1(3):184–194. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(17)30069-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rhone ET, Carmody JB, Swanson JR, Charlton JR. Nephrotoxic medication exposure in very low birth weight infants. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med . 2014;27(14):1485–1490. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2013.860522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moffett BS, Goldstein SL. Acute kidney injury and increasing nephrotoxic-medication exposure in noncritically-ill children. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol . 2011;6(4):856–863. doi: 10.2215/CJN.08110910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.De Broe ME, Verbist L, Verpooten GA. Influence of dosage schedule on renal cortical accumulation of amikacin and tobramycin in man. J Antimicrob Chemother . 1991;27(SupplC):41–47. doi: 10.1093/jac/27.suppl_c.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]