Abstract

OBJECTIVE

This study evaluates the value of inhaled budesonide (BUD) administration in neonatal respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) cases especially for near-term neonates.

METHODS

A randomized controlled trial involving 120 neonates with respiratory distress, which was diagnosed as RDS, was conducted from July 2016 to March 2018. The neonates studied were divided into 2 groups: group 1 (the inhaled BUD group), consisting of 60 neonates who received BUD (2 mL, 0.25-mg/mL suspension) inhalation, twice daily for 5 days; and group 2 (the placebo group), consisting of 60 neonates with RDS who received humidified distilled sterile water inhalation (2 mL). Downes score, RDS grades, and interleukin 8 (IL-8) levels were monitored and measured on the first and fifth days of incubation.

RESULTS

Statistically significant differences (SSDs) in RDS grades, Downes score, and IL-8 levels on the fifth day of admission were observed between groups 1 and 2 (p = 0.001) and between the first and fifth days of incubation in group 1 (p = 0.001). The SSDs in the duration of hospitalization (p = 0.001) and the number of neonates receiving mechanical ventilation (p = 0.032) were found between both groups.

CONCLUSIONS

Budesonide inhalation is associated with improvements in clinical and laboratory parameters in neonates with RDS

Keywords: budesonide, inhaled, neonate, respiratory distress, therapeutic

Introduction

Respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) is a widespread serious chest disorder, especially in premature neonates. The main risk factors for the development of RDS include prematurity and asphyxia.1,2 RDS is caused by defects in the secretion of surfactant due to immaturity of type II pneumocytes in the alveoli.3,4 Surfactant deficiency, leading to alveolar collapse, causes respiratory distress due to defective gas exchange.5,6 RDS could be prevented by several lines of treatment, including the administration of antenatal steroids to the mothers and exogenous surfactant to the premature neonates.7–10

Neonatal RDS is considered an inflammatory process in the immature lung; according to the severity of inflammatory injury to the alveoli, subsequent leakage of serum proteins will cause surfactant inactivation.11–15 Several studies have suggested that the inflammatory process is the main cause of pathogenesis in neonatal RDS.16 Inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin 8 (IL-8), play an important role in lung damage among preterm infants with RDS and chronic lung disease.17 The apoptotic process occurring in the epithelial cells of the neonatal lung, induced by the inflammatory process, causes inflammatory lung damage in neonatal RDS.18

Anti-inflammatory agents like corticosteroids have a beneficial role in the management of neonatal RDS by interfering with the inflammatory processes in the neonatal lungs19–22; however, systemic corticosteroids can have multiple adverse effects, including intestinal bleeding and growth failure.23,24 Local inhaled corticosteroids like budesonide (BUD) might reduce lung inflammation with subsequent improvement in the severity of neonatal RDS but with undetectable adverse effects, compared with systemic corticosteroids.25–27

Thus, this study evaluates the value of inhaled BUD administration in neonatal RDS cases especially for near-term neonates.

Materials and Methods

A prospective double-blinded randomized controlled trial involving 120 neonates with respiratory distress and diagnosed with RDS was conducted at the NICU of Tanta University Hospital from July 2016 to March 2018 and registered to the Thai Clinical Trials Registry (identification No.: TCTR20201228003). The neonates included in this study were divided into 2 groups by using the lottery method for randomization: group 1 (the inhaled BUD group) consisted of 60 neonates who received BUD inhalation, and group 2 (the placebo group) consisted of 60 neonates who received placebo.

Diagnosis of RDS. The clinical diagnosis of RDS was classified as grade 1 (tachypnea only), grade 2 (retraction with tachypnea), grade 3 (grade 2 with grunting), and grade 4 (grade 3 with cyanosis). With regard to chest x-ray findings, RDS was classified as grade 1 where fine granular densities are found, grade 2 where air bronchograms are observed, grade 3 where the characteristic ground-glass appearance is perceived, and grade 4 where white lungs are observed.28

Neonates diagnosed with RDS were included in this study, whereas neonates with any type of infection, respiratory diseases other than RDS, heart lesions, neurological lesions, and those who received exogenous surfactant were excluded from the study. The sample size and power analysis were calculated by using Epi-Info software statistical package, version 2002 (Atlanta, GA).29 The criteria used for sample size calculation were as follows: 95% confidence limit, 80% power of the study. The sample size was N = 60 for each study group.29

Drug Administration. Group 1 received BUD inhalation (2 mL, 0.25-mg/mL suspension) (AstraZeneca, Södertälje, Sweden) in addition to 2 mL of 0.9% saline via nebulization through a face mask connected to an oxygen flowmeter (5 L/min), twice daily for 5 days; and in neonates who needed invasive mechanical ventilation (MV), we used accessory ventilator pieces to deliver BUD. Group 2 received humidified distilled sterile water (2 mL). These procedures were done by the nurses responsible for those neonates, and the physicians were blinded to these procedures (double-blinded). The study had started immediately after diagnosis and admission (in the first 6 hours of birth in both groups) as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparative Characteristics Between the Studied Groups

| Demographics | Group 1: Inhaled BUD (n = 60) | Group 2: Placebo (n = 60) | Test | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight, mean ± SD, kg | 2.27 ± 0.8 | 2.28 ± 0.79 | t: 0.069 | 0.945 |

| Gestational age, mean ± SD, wk | 35.5 ± 1.2 | 35.6 ± 1.3 | t: 0.442 | 0.662 |

| Apgar score at 5 min, mean ± SD | 6.15 ± 0.3 | 6.2 ± 0.25 | t: 0.989 | 0.323 |

| Age on admission, mean ± SD, hr | 5.1 ± 0.9 | 5 ± 1 | t: 0.583 | 0.657 |

| Downes scores on admission, mean ± SD | 5.96 ± 0.12 | 5.95 ± 0.13 | t: 0.441 | 0.662 |

| RDS grades on admission, mean ± SD | 2.24 ± 0.45 | 2.23 ± 0.46 | t: 0.123 | 0.904 |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 45 (75) | 46 (77) | χ2: 0.046 | 0.831 |

| Female | 15 (25) | 14 (23) | ||

| Mode of delivery, n (%) | ||||

| Normal vaginal delivery | 18 (30) | 17 (28) | χ2: 0.040 | 0.841 |

| Caesarean section | 42 (70) | 43 (72) | ||

| Duration of hospitalization, mean ± SD, days | 8.2 ± 1.6 | 11 ± 1.9 | 8.729 | 0.001 |

| Mortality, n (%) | 1 (1.7) | 3(5) | 1.029 | 0.309 |

BUD, budesonide; RDS, respiratory distress syndrome

Data Collection. History, chest examination, and radiography (x-ray) were performed for all neonates studied to diagnose RDS; RDS grades and Downes scores were obtained on the first and fifth day after admission (first and fifth day of life), and C-reactive protein test was done to exclude infection.

Specimen Collection and Measurement of IL-8 and Proinflammatory Cytokines. From each neonate, 1 ml of blood sample was obtained on the first and fifth day of admission (first and fifth day of life). Serum IL-8 levels were estimated. The samples were stored at temperatures ranging from −20°C to −70°C. Serum IL-8 levels were measured with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.30

Statistical Analysis. All statistical analyses were performed with Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 21 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). Data were presented as mean ± standard deviation. The independent-samples t test was used to compare the 2 groups. Paired-samples t test was used for comparisons in the same group. For qualitative data, the χ2 test was used. p values less than 0.05 were used to denote statistical significance.

Results

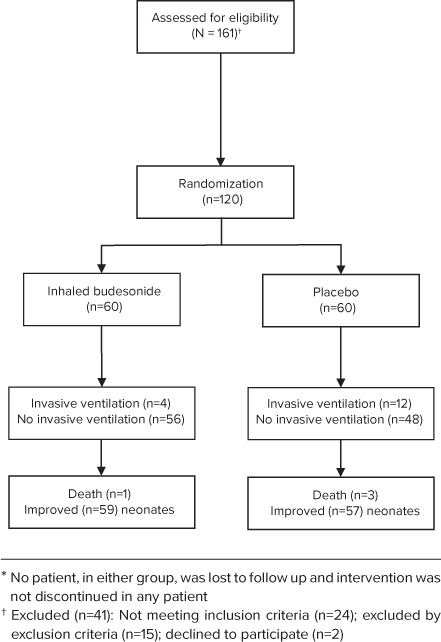

Initially, 161 near-term neonates were considered for inclusion; of these, 24 neonates were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. In addition, 15 neonates were excluded by exclusion criteria, and the parents of 2 neonates declined to participate because of transfer to another hospital. Finally, 120 neonates were included in this study, 60 neonates for inhaled budesonide group & 60 neonates for placebo group. Only 4 cases in inhaled budesonide group who had needed invasive ventilation while 12 cases in placebo group had needed invasive ventilation. Only 1 case was died in inhaled budesonide group while 3 cases were died in placebo group. (Figure).

Figure.

Consort or study flow chart of participating neonates in the study.

Local antifungal prophylaxis was orally administered to the neonates in group 1; thus, no side effects were detected after BUD inhalation in this study. Nurses responsible for these neonates performed this procedure and the physicians were blinded to it (double-blinded).

A non–statistically significant difference (non-SSD) in the comparative characteristics was observed between both groups (Table 1). In addition, non-SSDs in RDS grades and Downes scores on admission were found between both groups (p = 0.904 and 0.662, respectively) and between the first and fifth day after admission in group 2 (p = 0.066 and 0.070, respectively), whereas SSDs in RDS grades and Downes scores on the fifth day after admission were observed between both groups (p = 0.001 and 0.001, respectively) and between the first and fifth day after admission in group 1 (p = 0.001 and 0.001, respectively) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison Between RDS Grades, Downes Scores, and IL-8 Levels for Both Groups on the First and Fifth Days of Admission

| Group 1: Inhaled BUD (n = 60) | Group 2: Placebo (n = 60) | t test | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RDS grades, mean ± SD | ||||

| On first day of admission,* | 2.24 ± 0.45 | 2.23 ± 0.46 | 0.123 | 0.904 |

| On fifth day of admission | 0.9 ± 0.35 | 1.89 ± 0.61 | 11.629 | 0.001 |

| p value | 0.001 | 0.003 | ||

|

| ||||

| Downes scores, mean ± SD | ||||

| On first day of admission* | 5.96 ± 0.12 | 5.95 ± 0.13 | 0.441 | 0.662 |

| On fifth day of admission | 3.651 ± 0.9 | 5.59 ± 1.52 | 8.501 | 0.001 |

| p value | 0.001 | 0.070 | ||

|

| ||||

| Serum IL-8 levels, mean ± SD, pg/mL | ||||

| On first day of admission* | 519 ± 59.1 | 518 ± 60.2 | 0.089 | 0.927 |

| On fifth day of admission | 161.1 ± 68.7 | 489 ± 99.4 | 21.018 | 0.001 |

| p value | 0.001 | 0.056 | ||

BUD, budesonide; IL-8, interleukin 8; RDS, respiratory distress syndrome

* First day of life.

A non-SSD in serum IL-8 levels on admission was found between both groups (p = 0.927) and between the first and fifth day after admission in group 2 (p = 0.056), whereas an SSD in serum IL-8 levels was found on the fifth day after admission between both groups (p = 0.001) and between the first and fifth day after admission in group 1 (p = 0.001) (Table 2).

Binary logistic regression analysis of RDS grades, Downes scores, and serum IL-8 levels at the fifth day of admission showed that the p value of RDS grades, Downes scores, and serum IL-8 levels at the fifth day of admission were significant at 0.001, 0.004, and 0.001, respectively; this finding indicated that serum IL-8 levels were superior to RDS grades and Downes scores in the diagnosis of neonatal RDS (Table 3).

Table 3.

Binary Logistic Regression Analysis of RDS Grades, Downes Scores, and Serum IL-8 Levels at the Fifth Day of Admission

| Fifth Day of Admission | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDS grades | 0.632 | 0.297–0.854 | 0.001 |

| Downes scores | 0.429 | 0.145–0.745 | 0.004 |

| Serum IL-8, pg /mL | 0.597 | 0.397–0.854 | 0.001 |

IL-8, interleukin 8; RDS, respiratory distress syndrome

Moreover, an SSD in the number of cases requiring only nasal cannula–delivered oxygen (2 L/min) and the number of cases that required invasive MV was observed between both groups (p = 0.003 and 0.032, respectively), whereas a non-SSD in the number of cases that required nasal continuous positive airway pressure was found between both groups (p = 0.426) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Number of Cases According to Their Requirement for Various Types of Respiratory Support

| Cases Needing | Group 1: Inhaled BUD (n = 60) | Group 2: Placebo (n = 60) | χ2 Test | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal cannula, 2 L/min, n (%) | 16 (26.7) | 4 (6.7) | 8.637 | 0.003 |

| Nasal continuous positive airway pressure, n (%) | 40 (66.7) | 44 (73.3) | 0.631 | 0.426 |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation, n (%) | 4 (6.7) | 12 (20) | 4.607 | 0.032 |

BUD, budesonide

An SSD in the duration of neonatal hospitalization (days) was observed between both groups (p = 0.001). The mortality rate for the inhaled BUD group was 1.7% (n = 1) and was lower than that for the placebo group, which was 5% (n = 3) (Table 1). There were 2 cases (3.4%) of pneumothorax in the inhaled BUD group compared with 6 cases (10%) in the placebo group.

Discussion

This study investigated the therapeutic effect of BUD inhalation on neonatal RDS. The results of this study will contribute to the literature by highlighting the possibility of using inhaled BUD as a safe, cheap, and effective adjuvant therapy for neonatal RDS. Several studies have suggested that the process of inflammation is the main cause of pathogenesis in RDS in neonates,16 so we use IL-8 in addition to RDS grades and Downes score for follow-up in our cases.

This study showed an SSD in RDS grades, Downes scores, and serum IL-8 levels on the fifth day of incubation between both groups (p = 0.001) and between the first and fifth day after admission in group 1 (p = 0.001). In addition, SSDs in the duration of hospitalization and the number of cases requiring MV were found between groups 1 and 2 (p = 0.001 and 0.032, respectively). This study revealed that the mortality rate (1.7%) for the inhaled BUD group was lower than that (5%) for the placebo group, but the difference was insignificant (p = 0.309).

Moreover, this study revealed that the Downes scores of neonates who received BUD inhalation in group 1 improved when compared with those of neonates with RDS who did not receive BUD inhalation; this finding conforms to other studies showing that premature neonates with RDS who receive steroid inhalation have reduction in complications with no evident adverse effects.31

In addition, this study revealed that neonates with RDS who received BUD inhalation (group 1) had decreased RDS grades when compared with those in group 2 (the placebo group); this finding conforms to the findings of other studies in which early administration of inhaled BUD/formoterol in neonates with RDS leads to improved oxygenation.32

In this study, increased serum IL-8 levels were observed in neonates with RDS who did not receive BUD inhalation, and the same result was observed by some researchers who have reported that neonates with RDS have elevated levels of proinflammatory cytokines, especially IL-8, and serum IL-8 levels are correlated with the severity of RDS.33

Moreover, in this study, inhaled BUD–treated neonates with RDS had a shorter hospitalization duration than the neonates in the placebo group; this finding is in agreement with other studies reporting that BUD inhalation in neonates with RDS is associated with a decreased incidence of complications, which are caused by a long stay in an incubator with oxygen as in neonates with bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD).34

This study showed that no obvious side effect had occurred in the inhaled BUD group, and this result conforms to the results of other studies that have reported that BUD inhalation seems an obvious logical alternative to systemic steroids, with minimal or nearly absent obvious side effects with the same beneficial effect on RDS.35–39

In this study, the inhaled BUD group had both fewer neonates requiring MV and a lesser mortality rate than the placebo group, and this conforms to other studies stating that early steroid inhalation therapy may be beneficial to ventilated premature neonates with RDS40 and also conforms to studies that have concluded that steroid inhalation with surfactant is an effective and safe option for neonates with RDS for preventing BPD and reducing mortality.41

Some studies have shown that using a mixture of BUD and surfactant decreases the risk of BPD in premature neonates with RDS, which partially conforms to the results of this study.42 However, another study has concluded that inflammatory conditions and the number of complicated cases of BPD in neonates with RDS did not improve after BUD inhalation.43 The results of this study contradict the results of a study showing that steroid inhalation in neonates with RDS did not decrease the cytokine response or improve neonatal respiratory functions.44

The outcomes of several studies have suggested that BUD inhalation improves neonatal pulmonary functions with negligible adverse effects. In addition, evidence exists for the clinical efficacy and safety of BUD inhalation as a well-established anti-inflammatory drug for preventing and treating several pulmonary diseases.45,46

Conclusion

This study concluded that BUD inhalation improves the clinical and laboratory parameters in neonates with RDS; moreover, this study recommends BUD inhalation for neonates with RDS, and further studies should be conducted on the same topic, using a large number of neonates.

Glossary

ABBREVIATIONS

- BPD

bronchopulmonary dysplasia

- BUD

budesonide

- IL-8

interleukin 8

- MV

mechanical ventilation

- NICU

neonatal intensive care unit

- non-SSD

non–statistically significant difference

- RDS

respiratory distress syndrome

- SSD

statistically significant difference

References

- 1.Ye W, Zhang T, Shu Y et al. The influence factors of neonatal respiratory distress syndrome in Southern China: a case-control study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med . 2020;33(10):1678–1682. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2018.1526918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kothe TB, Sadiq FH, Burleyson N et al. Surfactant and budesonide for respiratory distress syndrome: an observational study. Pediatr Res . 2020;87(5):940–945. doi: 10.1038/s41390-019-0663-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Bernardo G, De Santis R, Giordano M et al. Predict respiratory distress syndrome by umbilical cord blood gas analysis in newborns with reassuring Apgar score. Ital J Pediatr . 2020;46(1):20. doi: 10.1186/s13052-020-0786-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matthay MA, Ware LB, Zimmerman GA. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Clin Investig . 2012;122(8):2731–2740. doi: 10.1172/JCI60331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roberts D, Brown J, Medley N, Dalziel SR. Antenatal corticosteroids for accelerating fetal lung maturation for women at risk of preterm birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev . 2017;3:CD004454. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004454.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kemp MW, Newnham JP, Challis JG et al. The clinical use of corticosteroids in pregnancy. Hum Reprod Update . 2016;22(2):240–259. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmv047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mirzamoradi M, Joshaghani Z, Hasani NF et al. Evaluation of the effect of antenatal betamethasone on neonatal respiratory morbidity in early-term elective caesarean. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med . 2020;33(12):1994–1999. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2018.1535587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee WY, Choi EK, Shin J et al. Risk factors for treatment failure of heated humidified high-flow nasal cannula as an initial respiratory support in newborn infants with respiratory distress. Pediatr Neonatol . 2020;61(2):174–179. doi: 10.1016/j.pedneo.2019.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang G, Hei M, Xue Z et al. Effects of less invasive surfactant administration (LISA) via a gastric tube on the treatment of respiratory distress syndrome in premature infants aged 32 to 36 weeks. Medicine (Baltimore) . 2020;99(9):e19216. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000019216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garbrecht MR, Klein JM, Schmidt TJ et al. Glucocorticoid metabolism in the human fetal lung: implications for lung development and the pulmonary surfactant system. Biol Neonate . 2006;89(2):109–119. doi: 10.1159/000088653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ma H, Yan W, Liu J. Diagnostic value of lung ultrasound for neonatal respiratory distress syndrome: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Med Ultrason . 2020;22(3):325–333. doi: 10.11152/mu-2485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yılmaz SS, Yücel B, Erbas IM et al. The utility of amniotic fluid pH and electrolytes for prediction of neonatal respiratory disorders. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med . 2020;33(2):253–257. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2018.1488961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Course C, Chakraborty M. Management of respiratory distress syndrome in preterm infants in Wales: a full audit cycle of a quality improvement project. Sci Rep . 2020;10(1):3536. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-60091-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang J, Liu X, Zhu T et al. Analysis of neonatal respiratory distress syndrome among different gestational segments. Int J Clin Exp Med . 2015;8(9):16273–16279. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Speer CP. Neonatal respiratory distress syndrome: an inflammatory disease? Neonatology . 2011;99(4):316–319. doi: 10.1159/000326619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li L, Dong L, Zhao D et al. Classical dendritic cells regulate acute lung inflammation and injury in mice with lipopolysaccharide induced acute respiratory distress syndrome. Int J Mol Med . 2019;44(2):617–629. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2019.4208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Westover AJ, Moss TJ. Effects of intrauterine infection or inflammation on fetal lung development. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol . 2012;39(9):824–830. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2012.05742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhu HP, Huang HY, Wu DM et al. Regulatory mechanism of NOV/CCN3 in the inflammation and apoptosis of lung epithelial alveolar cells upon lipopolysaccharide stimulation. Mol Med Rep . 2020;21(4):1872–1880. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2019.10655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang D, Yang Y, Zhao Y. Ibudilast, a phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor, ameliorates acute respiratory distress syndrome in neonatal mice by alleviating inflammation and apoptosis. Med Sci Monit . 2020;26:e922281. doi: 10.12659/MSM.922281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Doyle LW, Cheong JL, Ehrenkranz RA et al. Late (> 7 days) systemic postnatal corticosteroids for prevention of bronchopulmonary dysplasia in preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev . 2017;10(10):CD001145. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001145.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Onland W, De Jaegere AP, Offringa M et al. Systemic corticosteroid regimens for prevention of bronchopulmo-nary dysplasia in preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev . 2017;1(1):CD010941. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010941.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Poets CF, Lorenz L. Prevention of bronchopulmonary dysplasia in extremely low gestational age neonates: current evidence. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed . 2018;103(3):F285–F291. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2017-314264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Doyle LW, Cheong JL, Ehrenkranz RA et al. Early (< 8 days) systemic postnatal corticosteroids for prevention of bronchopulmonary dysplasia in preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev . 2017;10(10):CD001146. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001146.pub5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Venkataraman R, Kamaluddeen M, Hasan SU et al. Intratracheal administration of budesonide-surfactant in prevention of bronchopulmonary dysplasia in very low birth weight infants: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr Pulmonol . 2017;52(7):968–975. doi: 10.1002/ppul.23680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shinwell ES, Portnov I, Meerpohl JJ et al. Inhaled corticosteroids for bronchopulmonary dysplasia: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics . 2016;138(6):e20162511. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shah SS, Ohlsson A, Halliday HL et al. Inhaled versus systemic corticosteroids for the treatment of bronchopulmonary dysplasia in ventilated very low birth weight preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev . 2017;10(10):CD002057. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002057.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Filippone M, Nardo D, Bonadies L et al. Update on post-natal corticosteroids to prevent or treat bronchopulmo-nary dysplasia. Am J Perinatol . 2019;36(S 02):S58–S62. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1691802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu J. Respiratory distress syndrome in full-term neonates. J Neonatal Biol . 2012;S1:S1–e001. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Su Y, Yoon SS. Epi info—present and future. AMIA Annu Symp Proc . 2003;2003:1023. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leng SX, McElhaney JE, Walston JD et al. ELISA and multiplex technologies for cytokine measurement in inflammation and aging research. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci . 2008;63(8):879–884. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.8.879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Delara M, Chauhan BF, Le ML et al. Efficacy and safety of pulmonary application of corticosteroids in preterm infants with respiratory distress syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed . 2019;104(2):F137–F144. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2017-314046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Festic E, Carr GE, Cartin-Ceba R et al. Randomized clinical trial of a combination of an inhaled corticosteroid and beta agonist in patients at risk of developing the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med . 2017;45(5):798–805. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hammoud MS, Raghupathy R, Barakat N et al. Cytokine profiles at birth and the risk of developing severe respiratory distress and chronic lung disease. J Res Med Sci . 2017;22:62. doi: 10.4103/jrms.JRMS_1088_15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sadeghnia A, Beheshti BK, Mohammadizadeh M. The effect of inhaled budesonide on the prevention of chronic lung disease in premature neonates with respiratory distress syndrome. Int J Prev Med . 2018;9:15. doi: 10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_336_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shah VS, Ohlsson A, Halliday HL et al. Early administration of inhaled corticosteroids for preventing chronic lung disease in very low birth weight preterm neonates. Cochrane Database Syst Rev . 2017;1:CD001969. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001969.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bassler D, Plavka R, Shinwell ES et al. Early inhaled budesonide for the prevention of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. N Engl J Med . 2015;373(16):1497–1506. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1501917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bassler D, Shinwell ES, Hallman M et al. Long-term effects of inhaled budesonide for bronchopulmonary dysplasia. N Engl J Med . 2018;378(2):148–157. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1708831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shinwell ES. Are inhaled steroids safe and effective for prevention or treatment of bronchopulmonary dysplasia? Acta Paediatr . 2018;107(4):554–556. doi: 10.1111/apa.14180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sweet DG, Carnielli V, Greisen G et al. European Consensus Guidelines on the Management of Respiratory Distress Syndrome—2019 Update. Neonatology . 2019;115(4):432–450. doi: 10.1159/000499361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fok TF, Lam K, Dolovich M et al. Randomised controlled study of early use of inhaled corticosteroid in preterm infants with respiratory distress syndrome. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed . 1999;80(3):F203–F208. doi: 10.1136/fn.80.3.f203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhong YY, Li JC, Liu YL et al. Early intratracheal administration of corticosteroid and pulmonary surfactant for preventing bronchopulmonary dysplasia in preterm infants with neonatal respiratory distress syndrome: a meta-analysis. Curr Med Sci . 2019;39(3):493–499. doi: 10.1007/s11596-019-2064-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Halliday HL. Update on postnatal steroids. Neonatology . 2017;111(4):415–422. doi: 10.1159/000458460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Inwald DP, Trivedi K, Murch SH et al. The effect of early inhaled budesonide on pulmonary inflammation in infants with respiratory distress syndrome. Eur J Pediatr . 1999;158(10):815–816. doi: 10.1007/s004310051212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Parikh NA, Locke RG, Chidekel A et al. Effect of inhaled corticosteroids on markers of pulmonary inflammation and lung maturation in preterm infants with evolving chronic lung disease. J Am Osteopath Assoc . 2004;104(3):114–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tashkin DP, Lipworth B, Brattsand R. Benefit:risk profile of budesonide in obstructive airways disease. Drugs . 2019;79(16):1757–1775. doi: 10.1007/s40265-019-01198-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rüegger CM, Bassler D. Alternatives to systemic postnatal corticosteroids: inhaled, nebulized and intratracheal. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med . 2019;24(3):207–212. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2019.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]