Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Lewy Body Dementia (LBD), and Parkinson’s disease (PD) form a continuum that may explain multiple aspects of age-related neurodegeneration. Inflammaging, the long-term result of the chronic physiological stimulation of the innate immune system, is integral to this process. The gut microbiome plays an important role in inflammaging, as it can release inflammatory products and communicate with other organs and systems. Although AD and PD are molecularly and clinically distinct disorders, their causes appear to underlie LBD. All three conditions lie on a continuum related to AD, PD, or LBD in vulnerable persons. Inflammation in AD is linked to cytokines and growth factors. Moreover, cytokines and neurotrophins profoundly affect PD and LBD. Growth factors, neurotrophins and cytokines are also involved in embryo neural development. Cytokines influence gene expression, metabolism, cell stress, and apoptosis in the preimplantation embryo. The responsible genes are silenced around birth. But if activated by inflammaging and viruses in the brain decades later, they could destroy the same neural structures they created in utero. For this reason, the pathology and progression of AD, LBD, and PD would be unique. Embryonic reactivation could explain two well documented features of AD. 1) NSAIDs reduce AD risk but fail as a treatment. NSAIDs reduce AD risk because they suppress inflammaging. But they are not a treatment because they cannot silence the embryonic genes that have become active and damage the brain.

Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Lewy Body Dementia (LBD), and Parkinson’s disease (PD) form a continuum that may explain multiple aspects of age-related neurodegeneration. Inflammaging, the long- term result of the chronic physiological stimulation of the innate immune system, is integral to this process.

AD is a degenerative brain disease and the most common form of dementia, an irreversible, progressive disorder that slowly destroys memory and thinking skills, and, eventually, the ability to carry out the simplest tasks.

PD is a brain disorder that leads to shaking, stiffness, and difficulty with walking, balance, and coordination. Parkinson’s symptoms usually begin gradually and get worse over time.

LBD is related to PD and may share a similar genetic profile to AD. LBD usually affects people over 65 years old. Early signs of the disease include hallucinations, mood swings, and problems with thinking, movements, and sleep. Patients who initially have cognitive and behavioral problems are usually diagnosed as having dementia with Lewy bodies, but are sometimes mistakenly diagnosed with AD. Alternatively, many patients initially diagnosed with PD may eventually have difficulties with thinking and mood caused by Lewy body dementia. In both cases, as the disease worsens, patients become severely disabled and may die within eight years of diagnosis.

Inflammaging

Aging and many age-related diseases are closely related to inflammation. During aging, chronic, sterile, low-grade inflammation, called inflammaging, occurs, and is part of the pathogenesis of age-related diseases (Franceschi et al., 2018), age-related cerebral small vessel disease (Li et al., 2020), and waning adaptive immunity (Kasler and Verdin, 2021). Aging leads to a decline in adaptive immune responses with thymic atrophy, a reduction in the number of peripheral blood naïve T cells, and a relative increase in the frequency of memory T cells. These alterations lead to increased vulnerability to infectious diseases and reactivation of latent viral infections such as the herpesvirus varicella-zoster virus (VZV) and herpes simplex type I (HSV-1) (Kasler and Verdin, 2021).

In the brain, HSV-1 is of particular interest (Itzhaki et al., 2016). HSV-1 infection of neurons activates neurotoxic pathways typical of AD, and repeated HSV-1 reactivations in the brain of infected mice produce an AD-like phenotype (Lehrer and Rheinstein, 2020; Marcocci et al., 2020). Other viruses, too, such as VZV or cytomegalovirus, may lie dormant in the brain over many decades until reactivated by inflammaging or other stimulus. At this point, the AD/LBD/PD continuum comes into play.

The gut microbiome plays an important role in inflammaging, as it can release inflammatory products and communicate with other organs and systems.

Neurodegeneration and the Gut Microbiome

The gut microbiome has been implicated in PD (Fitzgerald et al., 2019; Willyard, 2021). In one report, mice without gut bacteria were less anxious than their healthy equivalents. When placed in a maze with open paths and walled-in paths, the mice preferred the exposed paths. Bacteria in the gut seemed to be influencing the animals’ brain and behavior (Neufeld et al., 2011).

In 1817, the English surgeon James Parkinson described some of the first cases of what would come to be known as Parkinson’s disease. One patient had numbness and prickling sensations in both arms. Parkinson noticed that the man’s abdomen seemed to contain “considerable accumulation.” Parkinson gave him a laxative. Ten days later the patient’s bowels were empty and his symptoms were gone (Willyard, 2021). In 2017, a systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrated that people with constipation are at a higher risk of developing PD compared with those without, and that constipation can predate PD diagnosis by over a decade (Adams-Carr et al., 2016).

In PD, the protein α-synuclein misfolds. The misfolded protein causes more misfolds, until harmful clumps of Lewy bodies form in the brain. Gut bacteria can produce proteins that have a similar structure to α-synuclein, so bacterial proteins might be providing a template for misfolding (Friedland, 2015). A strain of E. coli in the gut makes a protein, curli, which can stimulate other proteins, including α-synuclein, to misfold. The misfolded proteins might transmit the aberration up the vagus nerve to the brain, where misfolded α-synuclein is linked to PD symptoms (Sampson et al., 2020).

Stomach ulcers were once treated by removing all or part of the vagus nerve to reduce acid production in the stomach. Interestingly, people who had undergone this procedure had less risk of Parkinson’s disease (Svensson et al., 2015).

Genetics of Age-related Neurodegeneration

Five genes - GBA, BIN1, APOE, SNCA, and TMEM175 — in part define whether a person will have LBD, and some of these genes are involved in AD and PD (Chia et al., 2021). APOE and BIN1 are the two leading AD genes. At least 30 mutations in SNCA (the alpha synuclein gene) can cause PD. The TMEM175 p. M393T variant is responsible for the main signal in the chromosome 4p16.3 locus, conferring risk for PD by phosphorylation of alpha-synuclein. GBA encodes a lysosomal membrane protein that cleaves the beta-glucosidic linkage of glycosylceramide, an intermediate in glycolipid metabolism. Mutations in this gene cause Gaucher disease, a lysosomal storage disease characterized by an accumulation of glucocerebrosides, in addition to LBD.

Although AD and PD are molecularly and clinically distinct disorders, their causes appear to underlie LBD (Chia et al., 2021). All three conditions lie on a continuum linked to AD, PD, or LBD in vulnerable persons. The continuum would explain why in advanced disease all three conditions look similar. For example, hallucinations, while a hallmark of LBD, are seen in PD. A new drug, Nuplazid (pimavaserin), was FDA-approved for hallucinations and delusions in PD patients. The effect of pimavanserin could be mediated through a combination of inverse agonist and antagonist activity at serotonin 5-HT2A receptors and to a lesser extent at serotonin 5-HT2C receptors (Cusick and Gupta, 2020). During embryogenesis, these receptors are active in neuroepithelia of mouse brain and spinal cord, notochord, somites, cranial neural crest, and craniofacial mesenchyme (Lauder et al., 2000).

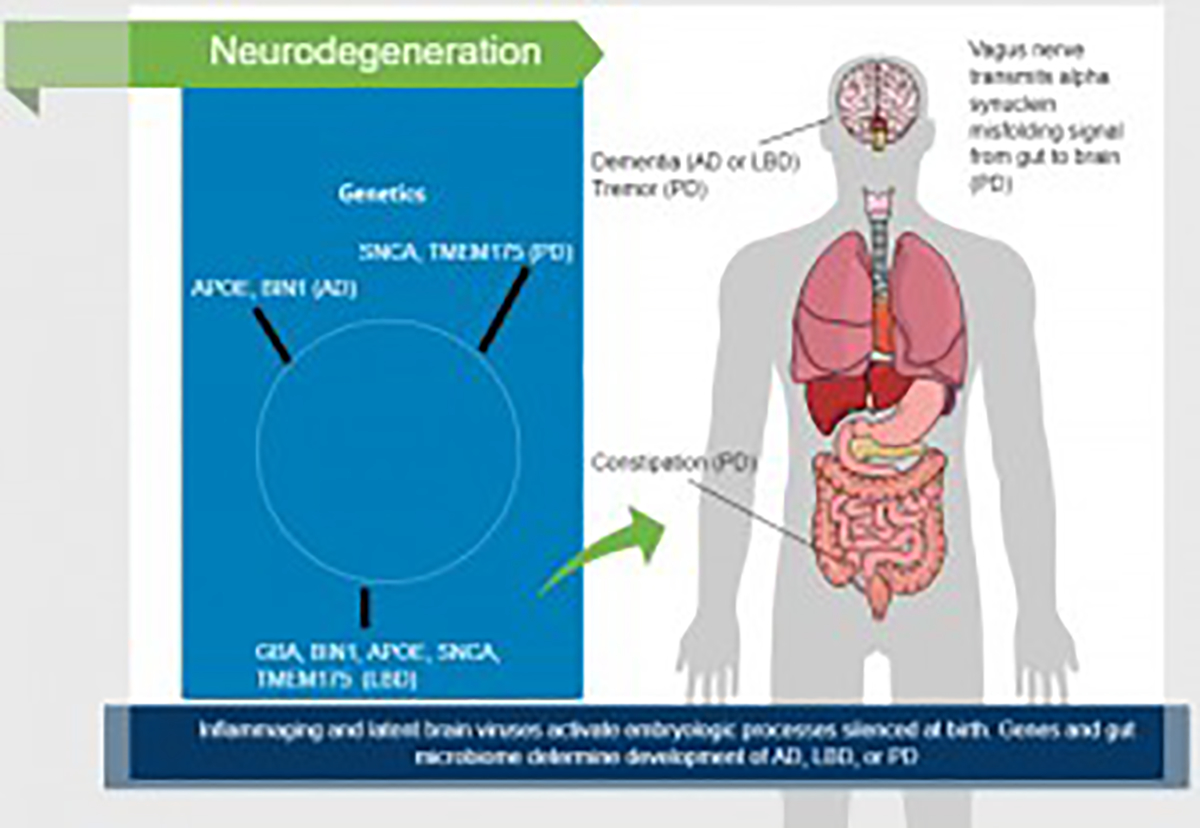

If the gut microbiome is not involved, and the genetics is conducive, the person will develop AD, the leftmost disease on the continuum. If the gut microbiome is involved, especially with preceding constipation, PD, the rightmost disease on the continuum will occur. But if the genetics includes the five genes above, LBD would be the likely outcome (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Factors involved in neurodegenration.

Cytokines, Neurotrophins and Growth Factors in Embryo Neurodevelopment and Old Age

Inflammation in AD is related to cytokines and growth factors (Ge and Lahiri, 2002). Moreover, cytokines and neurotrophins profoundly affect PD and LBD (Imamura et al., 2005; Nagatsu et al., 2000).

Growth factors, neurotrophins and cytokines are also involved in embryo neural development. Cytokines influence gene expression, metabolism, cell stress, and apoptosis in the preimplantation embryo. These substances initiate downstream events affecting implantation, placental development, fetal growth, and healthy pregnancy outcome (Robertson and Thompson, 2014). The genes responsible are silenced around birth. But if activated by inflammaging and viruses in the brain decades later, they could destroy the same neural structures they created in utero. For this reason, the pathology and progression of AD, LBD, and PD would be unique.

In the Braak staging of AD, initial changes are seen in the transentorhinal region of the temporal lobe. Then the destructive process reaches the entorhinal region, Ammon’s horn, and neocortex. Six stages of disease progression can be distinguished with respect to the location of the tangle-bearing neurons and the severity of changes: transentorhinal stages I-II: clinically silent cases; limbic stages III-IV: incipient Alzheimer’s disease; neocortical stages V-VI: fully developed Alzheimer’s disease (Braak and Braak, 1995). The advance from stages I-IV reflects the embryology of the rhinencephalon (Kier et al., 1997).

In the Braak staging of PD, involvement of the anterior olfactory nucleus, medulla, and pontine tegmentum occurs first; substantia nigra pathology occurs at mid-stage disease, similar to the embryology (Arts et al., 1996; Kuipers et al., 2006). In the last stages, Lewy bodies involve cortical areas (Dickson et al., 2010).

Embryonic reactivation could explain three features of AD.

NSAIDs reduce AD risk but fail as a treatment (Imbimbo et al., 2010). NSAIDs reduce AD risk because they suppress inflammaging (Ferrucci and Fabbri, 2018). But they are not a treatment because they cannot silence the embryonic genes that have become active and damaged the brain.

Children with fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) display altered performance in tasks of learning and memory, behaviors thought to be associated with the hippocampus; and altered hippocampal structure has been reported in some FAS children (Livy et al., 2003). In adults without mild cognitive impairment, daily low-quantity drinking was associated with lower dementia risk compared with infrequent higher-quantity drinking. A recent meta-analysis suggested a U-shaped pattern for the association between drinking and dementia, with a nadir at 4 drinks per week, whereas consuming 23 drinks per week or more was associated with a higher dementia risk (Koch et al., 2019). Light to moderate wine consumption seems to reduce the risk of dementia and cognitive decline in an age-dependent manner (Reale et al., 2020). Alcohol interferes with the embryology of the developing brain of a fetus, reducing intelligence. But alcohol could also interfere with embryologic reactivation in an old person, reducing the risk of AD.

Patients with severe Alzheimer’s disease experienced considerable improvements in both behavior and cognition within days of receiving low-dose radiation treatment (Cuttler et al., 2021). Ionizing radiation has profound detrimental effects on the developing brain, intelligence, and learning ability (Schull et al., 1990).

Cigarettes, Constipation, and a Possible PD Treatment

Tobacco smokers have reduced PD risk. The inverse relationship between smoking and PD is dose-dependent: the more a person smokes, the less chance that he or she will develop PD (Mappin-Kasirer et al., 2020).

As was mentioned above, some PD patients experience constipation long before they develop mobility problems; in addition, constipation is a frequent complaint of people who try to stop smoking. One in six smokers attempting to quit will become constipated; for one in eleven, the problem is severe. Constipation is reduced but still reported with nicotine replacement therapy (Hajek et al., 2003).

The reasons for the inverse association between tobacco smoking and PD are not fully understood. Some studies have suggested that nicotine may have neuroprotective properties and stimulate the release of dopamine. However, high-dose transdermal nicotine in PD patients was not beneficial (Villafane et al., 2018). Therefore, other components of tobacco may be responsible for the neuroprotective effect.

Tobacco has a long history of medicinal applications (Charlton, 2004). The leaves and juice were much used for skin disorders, possibly including basal cell cancer. Of most interest in Parkinson’s disease are the diterpenes in tobacco.

Diterpenes are a class of chemical compounds composed of four isoprene units. They are biosynthesized by plants, animals, and fungi via the HMG-CoA reductase pathway, with geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate being a primary intermediate. Diterpenes form the basis for biologically important compounds such as retinol, retinal, and phytol. They are antimicrobial, neuroprotective, and antiinflammatory (Kim et al., 2016; Yan et al., 2019). Diterpenes are present in coffee and tea, as well as in tobacco leaves, and coffee and tea drinkers have reduced PD risk (Gross et al., 1997; Katritzky et al., 2008).

Tobacco plants use both nicotine and diterpenoids to defend against hungry insects, such as tobacco hornworms. Diterpenoids are quite toxic. Tobacco plants have evolved an elaborate mechanism to maintain a balance between defending themselves and poisoning themselves. In wild tobacco (Nicotiana attenuata), two cytochrome P450 enzymes work within the biosynthetic pathway of 17-hydroxygeranyllinalool diterpene glycosides to help prevent the accumulation of toxic diterpene derivatives. The same diterpene derivatives are formed in an insect herbivore after ingestion and cause toxicity by inhibiting sphingolipid biosynthesis in both plant and insect (Li et al., 2021). Diterpenes are active against Parkinson’s disease and other forms of neurodegeneration, and have been suggested as therapeutic agents (Islam et al., 2016).

The beneficial effect of smoking on PD may be independent of the detrimental effect of constipation. Smoking may not be beneficial solely because it stimulates the bowel to empty and prevents constipation. A component of tobacco, perhaps the diterpenoids, could be an effective PD treatment.

Conclusion

Many questions remain about the AD/LBD/PD relationship and the role played by the gut microbiome. The disease mechanisms of AD disease and PD are likely multifactorial and the reactivation of embryologic pathways silenced at birth is likely one of them. Further studies may lead to new therapies.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Steven Lehrer, Specialty: Radiation Oncology, Institution: Department of Radiation Oncology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, Address: 1 Gustave L. Levy Place, New York, New York, 10029, United States.

Peter H Rheinstein, Specialty: Legal Medicine, Drug Regulation, Institution: Severn Health Solutions, Address: 621 Holly Ridge Road, Severna Park, MD, 21146, USA.

References

- Adams-Carr KL, Bestwick JP, Shribman S, Lees A, Schrag A, Noyce AJ. Constipation preceding Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 87(7):710–716, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arts M, Groenewegen H, Veening J, Cools A. Efferent projections of the retrorubral nucleus to the substantia nigra and ventral tegmental area in cats as shown by anterograde tracing. Brain research bulletin 40(3):219–228, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Braak E. Staging of Alzheimer’s disease-related neurofibrillary changes. Neurobiology of aging 16(3):271–278, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlton A Medicinal uses of tobacco in history. J R Soc Med 97(6):292–296, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chia R, Sabir MS, Bandres-Ciga S, Saez-Atienzar S, Reynolds RH, Gustavsson E, Walton RL, Ahmed S, Viollet C, Ding J, Makarious MB, Diez-Fairen M, Portley MK, Shah Z, Abramzon Y, Hernandez DG, Blauwendraat C, Stone DJ, Eicher J, Parkkinen L, et al. Genome sequencing analysis identifies new loci associated with Lewy body dementia and provides insights into its genetic architecture. Nat Genet 53(3):294–303, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cusick E, Gupta V. Pimavanserin, In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL), 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dickson DW, Uchikado H, Fujishiro H, Tsuboi Y. Evidence in favor of Braak staging of Parkinson’s disease. Movement Disorders 25(S1):S78–S82, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrucci L, Fabbri E. Inflammageing: chronic inflammation in ageing, cardiovascular disease, and frailty. Nat Rev Cardiol 15(9):505–522, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald E, Murphy S, Martinson HA. Alpha-synuclein pathology and the role of the microbiota in Parkinson’s disease. Front Neurosci 13:369, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franceschi C, Garagnani P, Parini P, Giuliani C, Santoro A. Inflammaging: a new immune-metabolic viewpoint for age-related diseases. Nat Rev Endocrinol 14(10):576–590, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedland RP. Mechanisms of molecular mimicry involving the microbiota in neurodegeneration. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 45(2):349–362, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge YW, Lahiri D. Regulation of promoter activity of the APP gene by cytokines and growth factors: implications in Alzheimer’s disease. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 973(1):463–467, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross G, Jaccaud E, Huggett A. Analysis of the content of the diterpenes cafestol and kahweol in coffee brews. Food and Chemical Toxicology 35(6):547–554, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajek P, Gillison F, Mcrobbie H. Stopping smoking can cause constipation. Addiction 98(11):1563–1567, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imamura K, Hishikawa N, Ono K, Suzuki H, Sawada M, Nagatsu T, Yoshida M, Hashizume Y. Cytokine production of activated microglia and decrease in neurotrophic factors of neurons in the hippocampus of Lewy body disease brains. Acta neuropathologica 109(2):141–150, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imbimbo BP, Solfrizzi V, Panza F. Are NSAIDs useful to treat Alzheimer’s disease or mild cognitive impairment? Front Aging Neurosci 2, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam MT, Da Silva CB, De Alencar MVOB, Paz MFCJ, Almeida FRDC, Melo-Cavalcante AaDC. Diterpenes: advances in neurobiological drug research. Phytotherapy Research 30(6):915–928, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itzhaki RF, Lathe R, Balin BJ, Ball MJ, Bearer EL, Braak H, Bullido MJ, Carter C, Clerici M, Cosby SL, Del Tredici K, Field H, Fulop T, Grassi C, Griffin WS, Haas J, Hudson AP, Kamer AR, Kell DB, Licastro F, et al. Microbes and Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 51(4):979–984, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasler H, Verdin E. How inflammaging diminishes adaptive immunity. Nature Aging 1(1):24–25, 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katritzky AR, Ramsden CA, Scriven EF, Taylor R. Comprehensive heterocyclic chemistry III, Elsevier; Amsterdam, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kier EL, Kim JH, Fulbright RK, Bronen RA. Embryology of the human fetal hippocampus: MR imaging, anatomy, and histology. American journal of neuroradiology 18(3):525–532, 1997. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim CS, Subedi L, Kim SY, Choi SU, Kim KH, Lee KR. Diterpenes from the trunk of Abies holophylla and their potential neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory activities. Journal of natural products 79(2):387–394, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch M, Fitzpatrick AL, Rapp SR, Nahin RL, Williamson JD, Lopez OL, Dekosky ST, Kuller LH, Mackey RH, Mukamal KJ, Jensen MK, Sink KM. Alcohol consumption and risk of dementia and cognitive decline among older adults with or without mild cognitive impairment. JAMA Network Open 2(9):e1910319–e1910319, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuipers R, Mouton LJ, Holstege G. Afferent projections to the pontine micturition center in the cat. Journal of Comparative Neurology 494(1):36–53, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauder JM, Wilkie MB, Wu C, Singh S. Expression of 5-HT(2A), 5-HT(2B) and 5-HT(2C) receptors in the mouse embryo. Int J Dev Neurosci 18(7):653–662, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehrer S, Rheinstein PH. Alignment of Alzheimer’s disease amyloid-beta peptide and herpes simplex virus-1 pUL15 C-terminal nuclease domain. J Alzheimers Dis Rep 4(1):373–377, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Halitschke R, Li D, Paetz C, Su H, Heiling S, Xu S, Baldwin IT. Controlled hydroxylations of diterpenoids allow for plant chemical defense without autotoxicity. Science 371(6526):255–260, 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T, Huang Y, Cai W, Chen X, Men X, Lu T, Wu A, Lu Z. Age-related cerebral small vessel disease and inflammaging. Cell Death & Disease 11(10):1–12, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livy D, Miller EK, Maier SE, West JR. Fetal alcohol exposure and temporal vulnerability: effects of binge-like alcohol exposure on the developing rat hippocampus. Neurotoxicology and teratology 25(4):447–458, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mappin-Kasirer B, Pan H, Lewington S, Kizza J, Gray R, Clarke R, Peto R. Tobacco smoking and the risk of Parkinson disease: A 65-year follow-up of 30,000 male British doctors. Neurology 94(20):e2132–e2138, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcocci ME, Napoletani G, Protto V, Kolesova O, Piacentini R, Li Puma DD, Lomonte P, Grassi C, Palamara AT, De Chiara G. Herpes simplex virus-1 in the brain: the dark side of a sneaky infection. Trends Microbiol, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagatsu T, Mogi M, Ichinose H, Togari A. Changes in cytokines and neurotrophins in Parkinson’s disease. Advances in Research on Neurodegeneration:277–290, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neufeld K, Kang N, Bienenstock J, Foster JA. Reduced anxiety-like behavior and central neurochemical change in germ-free mice. Neurogastroenterology & Motility 23(3):255–e119, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reale M, Costantini E, Jagarlapoodi S, Khan H, Belwal T, Cichelli A. Relationship of wine consumption with Alzheimer’s disease. Nutrients 12(1):206, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson SA, Thompson JG. Growth factors and cytokines in embryo development, In: Culture Media, Solutions, and Systems in Human ART. pp 112–131. (Ed. Quinn P.) Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson TR, Challis C, Jain N, Moiseyenko A, Ladinsky MS, Shastri GG, Thron T, Needham BD, Horvath I, Debelius JW. A gut bacterial amyloid promotes α-synuclein aggregation and motor impairment in mice. Elife 9:e53111, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson E, Horváth-Puhó E, Thomsen RW, Djurhuus JC, Pedersen L, Borghammer P, Sørensen HT. Vagotomy and subsequent risk of P arkinson’s disease. Annals of neurology 78(4):522–529, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villafane G, Thiriez C, Audureau E, Straczek C, Kerschen P, Cormier-Dequaire F, Van Der Gucht A, Gurruchaga JM, Quere-Carne M, Evangelista E, Paul M, Defer G, Damier P, Remy P, Itti E, Fenelon G. High-dose transdermal nicotine in Parkinson’s disease patients: a randomized, open-label, blinded-endpoint evaluation phase 2 study. Eur J Neurol 25(1):120–127, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willyard C How gut microbes could drive brain disorders. Nature 590(7844):22–25, 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan N, Du Y, Liu X, Zhang H, Liu Y, Zhang Z. A review on bioactivities of tobacco cembranoid diterpenes. Biomolecules 9(1), 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]