Abstract

Purpose

This meta-analysis aims to evaluate inappropriate antibiotic prescribing in the Gulf region and determine the effect of pharmacist-led antimicrobial stewardship (AMS) programmes on reducing inappropriateness.

Method

Articles were searched, analysed, and quality assessed through the risk of bias (ROB) quality assessment tool to select articles with a low level of bias. In step 1, 515 articles were searched, in step 2, 2360 articles were searched, and ultimately 32 articles were included by critical analysis. Statistical analysis used to determine risk ratio and standard mean differences were calculated using Review manager 5.4; 95% confidence intervals were calculated using the fixed-effect model. The I2 statistic assessed heterogeneity. In statistical heterogeneity, subgroup and sensitivity analyses, a random effect model was performed. The α threshold was 0.05. The primary outcome was inappropriateness in antibiotic prescribing in the Gulf region and reduction of inappropriateness through AMS.

Result

Detailed review and analysis of 18 studies of inappropriate antibiotic prescribing in the Gulf region showed the risk of inappropriateness was 43 669/100 846=43.3% (pooled RR 1.31, 95% CI 1.30 to 1.32). Test with overall effect was 58.87; in the second step 28 AMS programmes led by pharmacists showed reduced inappropriateness in AMS with pharmacist versus pre-AMS without pharmacist (RR 0.36, 95% CI 0.32 to 0.39).

Conclusion

Inappropriate antibiotic prescribing in the Gulf region is alarming and needs to be addressed through pharmacist-led AMS programmes.

Keywords: drug monitoring, evidence-based medicine, health services administration, pharmacy service, hospital, drug misuse

Background

Antimicrobial resistance is increasing globally, affecting cost, mortality and length of hospital stay. A recently published study showed that by 2050 the leading cause of death will be bacterial infection unless resistance is controlled.1 A survey of antibiotic resistance in the Gulf region found the susceptibility of community-acquired respiratory tract isolates in the region to be alarming. The report shows that ‘there are large country-specific differences in antibiotic susceptibility even within the same region, with overall antibiotic resistance being the highest in S. pneumoniae and isolates from the UAE’.2 A study conducted in eight hospitals in Saudi Arabia showed that the most resistant antipseudomonal agent was meropenem followed by ticarcillin, imipenem, and piperacillin; almost 13% of the strains were multidrug resistant.3 Since 1998, higher rates of resistant bacteria have been seen in Saudi Arabia. Most of these cases could be attributed to greater and irrational use of antibiotic drugs.4

Inappropriate antibiotic prescribing is associated with the emergence of multidrug resistance, which ultimately increases the mortality rate. For example, one study found inappropriate antibiotic prescribing was an essential determinant of multidrug resistance associated with a threefold increase in in-hospital mortality.5 In a survey of European medical final students, 66% agreed that antibiotic resistance was due to prescribed antibiotics being the wrong choice.6 Another study, this time in Singapore, showed that inappropriate prescribing of antimicrobials was responsible for increased antimicrobial resistance that could only be resolved with appropriate antimicrobial prescribing.7

Rational prescribing can help to reduce antimicrobial resistance. Antimicrobial stewardship (AMS) programmes can help to increase the rational prescribing of antibiotics. A study showed that an AMS programme helped to increase appropriate antimicrobial prescribing by up to 89.3%.8 The pharmacist plays a vital role in the stewardship team. However, the extent of inappropriate antibiotic prescribing and the impact of the pharmacist on the rational prescribing of antibiotics through AMS programmes is unclear.

This study evaluates inappropriate antibiotic prescribing in the Gulf region and determines the effect of pharmacist-led AMS programmes on rational prescribing.

Methodology

The methodology for searching articles involved a two-step process. In the first step, we determined the level of inappropriate antimicrobial prescribing in the Gulf region, and in the second step we studied the impact of the pharmacist on inappropriate prescribing through a pharmacist-led AMS programme. Our methodology adheres to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines (see PRISMA checklist: online supplemental appendix 1)

ejhpharm-2021-002914supp001.pdf (133.6KB, pdf)

Data sources

In step 1, antimicrobial prescribing patterns with inappropriate prescribing were identified by searching PubMed, Embase and Elsevier. The search included all English language articles. Key words used were: ‘antibiotic’, ‘prescribing’, and ‘Gulf’, ‘Saudi Arabia’,‘UAE’, ‘Qatar’, ‘Bahrain’, ‘Kuwait’, ‘Oman’ and ‘Yemen’. Only original articles were included, while reviews, meta-analyses, surveys and questionnaires showing prescribing practices and inappropriateness were excluded.

In step 2, AMSs were identified by searching PubMed, Embase and Elsevier. We included all stewardships, with English language restriction, published from 2012 to 2020. Keywords used were: ‘antimicrobial stewardship’, ‘antibacterial stewardship’, ‘mortality’, ‘appropriateness’, ‘led by pharmacist’, ‘pharmacist’, ‘rational prescribing’, ‘antifungal stewardship’, ‘impact of the pharmacist’, ‘impact on cost’, ‘outcomes of stewardship’, ‘hospital readmission’, and ‘antibiotic consumption’. We only included articles with those values representing the inappropriate prescribing of antibiotics before and after AMS programmes led by the pharmacist. We restricted our search to the primary literature; systematic reviews, meta-analyses and all other types of reviews were excluded. We manually searched the reference lists of systematic reviews to check their inclusion in our analysis.

The search strategy is illustrated in online supplemental appendix 1.

Study selection

In step 1, we included primary literature on all antimicrobial prescribing patterns in the Gulf region. The Gulf region includes seven countries (UAE, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Qatar, Oman, Yemen and Bahrain). Articles with inappropriate antibiotic prescribing practices were included. Topical antibiotic prescribing studies were excluded, and studies conducted in countries other than those in the Gulf region were also excluded. In step 2, we included primary literature on all types of AMS programmes (antibiotics, antifungal, antiviral) led by pharmacists, whether retrospective, prospective or quasi-experimental studies. Dichotomous results were extracted from the AMS programme with pharmacists compared with the pre-AMS programme without pharmacists. Only studies with inappropriate antibiotic prescribing as a clinical outcome were included in our analysis. Reviews and abstracts without complete data, studies in languages other than English, and stewardship programmes with antimicrobial outcomes other than inappropriate prescribing practices were excluded.

Two investigators (RKM, MJA) independently assessed eligibility. In case of any discrepancy, a third observer (SWG) adjudicated the eligibility. The extraction forms and risk of bias assessments are available in the online supplemental appendix 1.

Quality assessment

Two authors (RKM, SMG) independently assessed trial quality. Internal validity was analysed with the JSM quality assessment tool. These articles were then rated according to methodological quality: high, moderate, or low.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was inappropriate antibiotic prescribing practices in the Gulf region and the impact of AMS programmes led by pharmacists in reducing inappropriate antimicrobial prescribing. Two reviewers (MJA, SMG) independently extracted the data for all the outcomes of interest.

Inappropriate prescribing

Antibiotic prescribing is termed ‘ inappropriate’ if the prescribing does not meet prescribing guidelines. If the dose, frequency, dosage form, indication and route of administration were not correct then the prescribing was considered to be inappropriate.

Principal summary measures and statistical analysis

Analyses were done using RevMan software version 5.4 (http://www.cc-ims.net/revman). We calculated risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (95 % CI) for all studies, using the fixed-effect model in the first approach. Heterogeneity was investigated with the I2 statistic. It measures the proportion of overall variation attributable to between-study heterogeneity. I2 values of 25%, >50%, and >75% refer respectively to low, substantial, and considerable degrees of heterogeneity. In case of statistical heterogeneity, we tried to explain this with subgroup and sensitivity analyses rather than with funnel plots. Statistical significance was defined with an α threshold at 0.05.

Results and findings

General characteristics

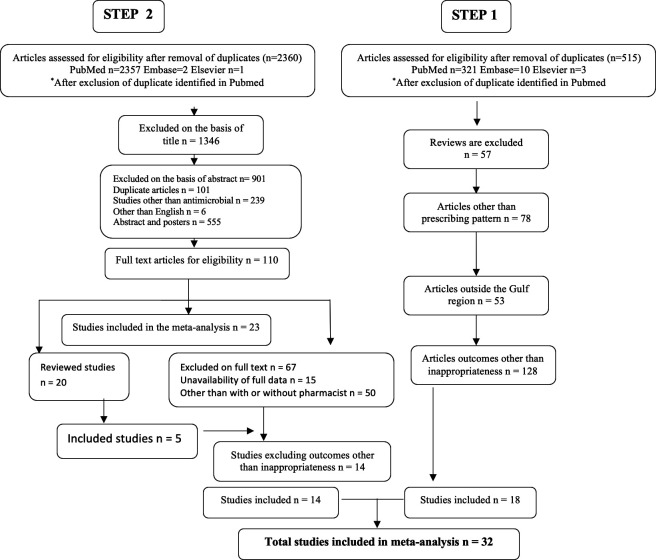

In the first step, 515 articles were searched and, after removing duplications, 330 were from PubMed, 10 from Embase and three from Elsevier (figure 1). Articles excluded were 57 reviews, 78 articles without prescribing patterns, 53 that came from outside the Gulf region, and 128 articles with outcomes other than inappropriateness; the remaining 18 articles were included.9–26 In the second step, a total of 2453 articles were searched, and after removing duplications 2357 were from PubMed, two from Embase and one from Elsevier. Nine hundred and one articles were excluded based on the abstract, and 1349 based on the title; 110 articles were included and studied thoroughly. Of these 110 articles, 23 were included and 67 were excluded (unavailability of complete data, outcome requirement and stewardship other than pharmacist but with the physician). These 23 studies were further reviewed, and five only were included in the meta-analysis; in the end, 14 studies with inappropriateness were included.27–40 Therefore a total 32 studies were eventually included in the study; details of the study characteristics are provided in online supplemental table 1.

Figure 1.

General characteristics of studies included in the meta-analysis.

Quality assessment

Quality assessment was performed using the JSM tool for all the studies screened and the included studies that reported low or medium levels of bias. Quality assessment details are attached as a supplementary document. Articles were assessed in detail with purpose, methodology, results, and discussions. Online supplemental table 2 shows the quality assessment tool results.

Inappropriate antibiotic prescribing

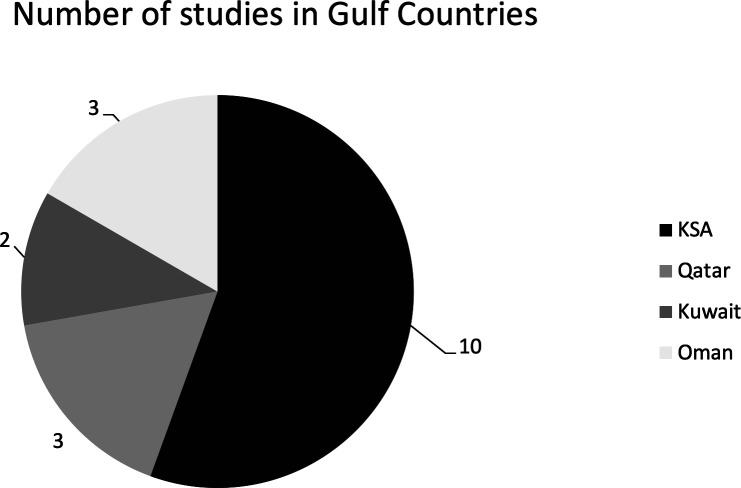

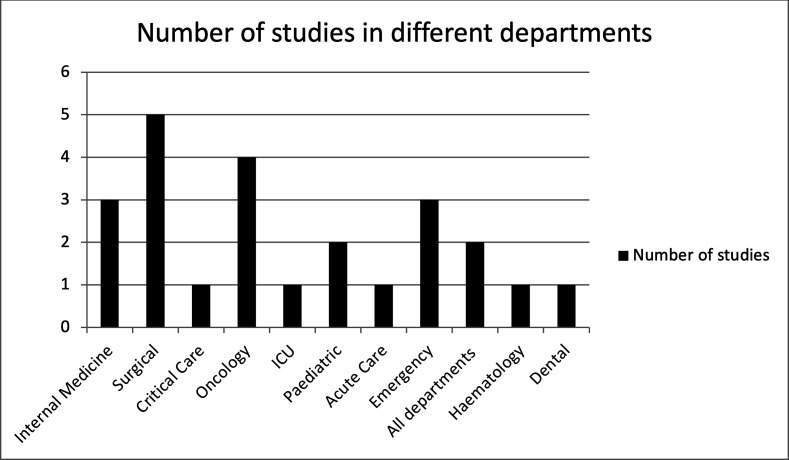

The inappropriate prescribing of antibiotics in all departments in the tertiary care setting were measured. Among all seven Gulf countries, inappropriate prescribing was reported in four countries: Saudi Arabia with 10 primary articles, three studies in Oman and Qatar, two in Kuwait, while no studies were found in UAE, Bahrain and Yemen (figure 2). Studies on the prescribing patterns of antibiotics with inappropriateness have been available in Saudi Arabia since 1988, and there was a new study in Oman in 2020. Prescribing patterns have been studied in different departments of the hospitals, and it was found that most of the studies took place in the surgical,5 oncology,4 emergency, and internal medicine departments,3 3 as shown in figure 3. Eighteen articles discussed inappropriate antibiotic prescribing patterns. We found that 14 studies showed the positive outcome of reducing inappropriate antimicrobial prescribing, as shown in figure 2. The risk of inappropriate prescribing of antimicrobials is less in AMS with a pharmacist than pre-AMS without a pharmacist.

Figure 2.

Number of studies in the different countries of the Gulf region.

Figure 3.

Number of studies in different departments of hospitals in the Gulf region.

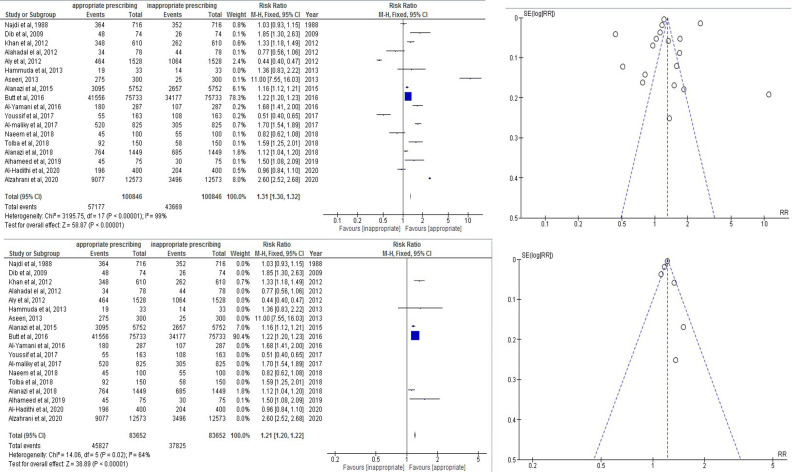

Pooled analysis

Total inappropriateness in prescribing pattern in the Gulf region in 18 studies was 43 669/100 846=43.3% (pooled RR 1.31, 95% CI 1.30 to 1.32). The test with the overall effect was 58.87 (p<0.00001). Heterogeneity was calculated at about I2=99%. A funnel plot used to reduce the bias is shown in online supplemental figure 4. Inappropriateness was reduced to I2=64%.(figure 4)

Figure 4.

The 18 studies with inappropriateness and reduction of bias through funnel plots.

Sub-group analysis

Calculation of inappropriateness differed from one study to another. Al-Hameed calculated the inappropriate prescribing with the dose and monitoring of antibiotics like vancomycin, and compared with standard guidelines such as the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists/Infectious Diseases Society of America (ASHP/IDSA) guidelines,9 showed 40% of inappropriate dosing and monitoring. Youssif calculated the inappropriate antibiotic prescribing in the surgical ward for broad-spectrum antibiotics by requesting culture within 24 hours and the number of days to de-escalate once the results of culture were received,10 and showed 66% of inappropriate prescribing in the surgical ward. Aly checked the antibiotic prescribing concordance with hospital guidelines and found that 69.6% of prescribed antibiotic prescriptions were not concordant.11 Alzahrani audited the antibiotic prescribing pattern in the dental department and found that antibiotics were prescribed in 27.8% of consultations in which antibiotics were not recommended.12 Alanazi reviewed the antibiotic prescribing pattern in the emergency department and found inappropriate prescribing with major errors in dose (37%), then duration, frequency and selection of antimicrobials, and found overall inappropriateness of 41.4%13; and in another study in 2015 found inappropriateness on the same basis in the emergency department of 46.12%.14 A study in King Abdulaziz university hospital found that in 56.4% of patients with renal failure, antibiotic doses were not adjusted.15 Antibiotic prescribing compliance with the local guidelines and the overall restricted antibiotic policy adherence at Sultan Qaboos University Hospital found that 36.96% of antibiotic prescribing were not up to the mark.16 Another study in Oman checked the rational prescribing of antibiotics depending on local standard guidelines, and the experience of the infectious diseases consultant found irrational antibiotic prescribing in 37.28% of cases.17 Meropenem inappropriate prescribing in Oman—with inappropriateness assessed by specific meropenem-use criteria developed from pre-specified, literature-based criteria and then modified by an expert panel of infectious diseases specialists—found inappropriateness in 51% of cases.18 Antibiotic misuse in the paediatric department of Kuwait was assessed using local guidelines and found mistakes such as inappropriate use, duration, route, unnecessary use, and a combination of the factors, in 49.16% of cases.19 Unjustified piperacillin-tazobactam prescription in Qatar, identified by setting specific criteria, found 42.95% of unjustified use cases.20 Empirical treatment for febrile neutropenia using King Abdulaziz Medical City-Western Region (KAMC-WR) empirical therapy guidelines found that 55% of guidelines were non-compliant with treatment.21 Antibiotic prophylaxis assessed against guidelines published by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN), ASHP and the Saudi Ministry of Health (MOH) found that 38.6% of cases of antibiotic prophylaxis were not recommended.22 Vancomycin use in a Saudi Arabian medical centre assessed by a clinical pharmacist along with an infectious disease consultant found that 35% of cases were inappropriate.23 Antimicrobial use in oncology in Qatar assessed by local prescribing restriction guidelines found 42% of prescriptions did not comply with the guidelines.24 Paediatric antibiotic dosing standard assessed with the standard if >110% or <90% were considered an inappropriate dose found a dosing error rate of 30%25 before implementing stewardship. Antibiotics for upper respiratory tract infection in the outpatient setting assessed by the expert opinion of infectious diseases specialists found a 45% level of inappropriateness.26

Reduction in inappropriateness

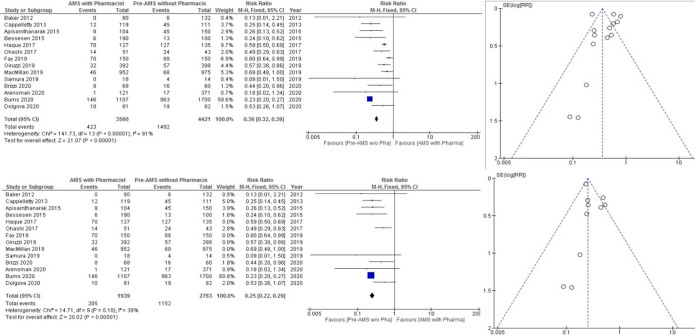

There have been reports of a total of 14 AMS programmes led by pharmacists in the last 8 years, discussing appropriate antibiotic therapy. Eight AMS programmes led by pharmacist were from the USA, two were from Japan, and one each from Spain, Thailand, and Pakistan. Nine studies were retrospective, and five were prospective in nature. Different strategies were used in every AMS programme. We found that all 14 studies showed a positive outcome in reducing inappropriate antimicrobial prescribing, as shown in figure 5. The risk of inappropriate prescribing of antimicrobials was less in AMS with pharmacist than pre-AMS without pharmacist.

Figure 5.

Fourteen antimicrobial stewardship (AMS) results for inappropriate antimicrobial prescribing.

Pooled analysis

Total inappropriateness in AMS with a pharmacist was 423/3560 (11.88%), whereas in pre-AMS without a pharmacist it was 1492/4421 (33.74%) (pooled RR 0.36, 95% CI 0.32 to 0.39). The test with the overall effect was 21.27 (p<0.00001). Heterogeneity was calculated at about I2=91%. A funnel plot was used to reduce the bias. Inappropriateness was reduced to I2=39%.

Discussion

Antibiotic prescribing patterns are studied all over the world, including in the Gulf region. Antibiotic prescription with use and indication, and overall trends are studied with the rational prescribing. Antibiotic prescribing patterns in the Gulf region show a variation in all departments concerning inappropriate prescribing. Standards of inappropriate prescribing differ from study to study, some using local or international guidelines, dosing, frequency, monitoring, indication and prophylaxis. It has been observed that most of the inappropriate antibiotic prescribing studies in the Gulf are from Saudi Arabia and three other countries, while UAE, Bahrain and Yemen have no studies that show the levels of inappropriate antibiotic prescribing in the region. Surgical ward inappropriate antibiotic prescribing is most studied in the Gulf region. This department is responsible for both prophylaxis and treatment and is related to the emergency department, so the chances of a lack of concordance with the guidelines and policies are high. Oncology, emergency, and internal medicine departments for long-term patients or patients with multiple disorders need attention as the chances of inappropriate antibiotic use are high. A study in Kuwait in 2012 showed very high inappropriate antibiotic prescribing as physicians did not adhere to guidelines in almost 70% of the incredibly high cases.11 Another study showed least inappropriate antibiotic prescribing practice as low as 27%,12 showed low inappropriateness in the dental department in Saudi Arabia, and showed 27% of cases of overuse of antibiotics. It showed that the average level of inappropriate antibiotic prescribing in the Gulf region is very high, and recommends education, stewardships, seminars, awareness, concordance with guidelines and implementation of clinical pharmacists in hospitals and infectious disease specialists. A study in Colombia showed a level of inappropriate antibiotic prescribing for acute bronchiolitis at 65%.41 A study in the USA reported 18% of inappropriate prescribing of antibiotics in 18 million non-elderly population.42 Even with this number of patients, the level of inappropriate antibiotic prescribing in the USA is less than the least reported in the Gulf region. A 9 year study of antibiotic inappropriateness in a US emergency department showed that 70% of the cases with bronchiolitis had been prescribed antibiotics without documented bacterial co-infection.

AMS programmes can help to reduce inappropriate prescribing patterns. The pharmacist is an integral part of the healthcare system and involves drug dispensing, monitoring and compounding, and working as a clinical pharmacist to help develop the stewardship programmes. The search for studies on AMS programmes led by pharmacists shows a positive impact on inappropriate antibiotic prescribing in all 14 studies included in the analysis. Average inappropriateness was 37% which was reduced to 11.88% after the implementation of a pharmacist-led AMS. An AMS programme conducted in the Gulf region has stated that the level of appropriateness was corrected from 30% to 100% in a medical intensive care unit of a tertiary care hospital in Saudi Arabia.43 Another stewardship in a tertiary care hospital in Qatar stated that appropriateness improved to 95.7% with the help of AMS.44 A lack of pharmacist-led stewardship is noted in the Gulf region and need improvements. A survey of 47 participants from the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) reports the reduction of inappropriate prescribing at 68%, which is still not up to the mark.45 Other factors need to be studied beyond stewardship, as infection control measures and self-medication have an impact on resistance and stewardship programmes.

Conclusion

Inappropriate prescribing of antibiotics in the Gulf region is widespread and needs to be addressed with AMS programmes. There have been few reports on the stewardship programmes in the Gulf region, and pharmacist-led AMS programmes that may help to improve appropriate antibiotic use are still not in operation in the region.

Footnotes

Contributors: All the authors have contributed equally to this research manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

References

- 1. O’Neill J. Tackling drug-resistant infections globally: final report and recommendations: the review on antimicrobial resistance, 2019: 1–35. https://amr-review.org/sites/default/files/160518_Finalpaper_withcover.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jamsheer A, Rafay AM, Daoud Z, et al. Results from the survey of antibiotic resistance (SOAR) 2011-13 in the Gulf states. J Antimicrob Chemother 2016;71 Suppl 1:i45–61. 10.1093/jac/dkw064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Khan MA, Faiz A. Antimicrobial resistance patterns of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in tertiary care hospitals of Makkah and Jeddah. Ann Saudi Med 2016;36:23–8. 10.5144/0256-4947.2016.23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rotimi VO, al-Sweih NA, Feteih J. The prevalence and antibiotic susceptibility pattern of gram-negative bacterial isolates in two ICUs in Saudi Arabia and Kuwait. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 1998;30:53–9. 10.1016/S0732-8893(97)00180-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zilberberg MD, Shorr AF, Micek ST, et al. Multi-drug resistance, inappropriate initial antibiotic therapy and mortality in gram-negative severe sepsis and septic shock: a retrospective cohort study. Crit Care 2014;18:596. 10.1186/s13054-014-0596-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dyar OJ, Pulcini C, Howard P, et al. European medical students: a first multicentre study of knowledge, attitudes and perceptions of antibiotic prescribing and antibiotic resistance. J Antimicrob Chemother 2014;69:842–6. 10.1093/jac/dkt440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hsu LY, Kwa AL, Lye DC, et al. Reducing antimicrobial resistance through appropriate antibiotic usage in Singapore. Singapore Med J 2008;49:749–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yanai M, Ogasawara M, Hayashi Y, et al. Impact of interventions by an antimicrobial stewardship program team on appropriate antimicrobial therapy in patients with bacteremic urinary tract infection. J Infect Chemother 2018;24:206–11. 10.1016/j.jiac.2017.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Alhameed A, Khansa S, Hasan H, et al. Bridging the gap between theory and practice; the active role of inpatient pharmacists in therapeutic drug monitoring. Pharmacy 2019;7:20. 10.3390/pharmacy7010020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Youssif E, Aseeri M, Khoshhal S. Retrospective evaluation of piperacillin–tazobactam, imipenem–cilastatin and meropenem used on surgical floors at a tertiary care hospital in Saudi Arabia. J Infect Public Health 2018;11:486–90. 10.1016/j.jiph.2017.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Aly NY, Omar AA, Badawy DA, et al. Audit of physicians' adherence to the antibiotic policy guidelines in Kuwait. Med Princ Pract 2012;21:310–7. 10.1159/000334769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Alzahrani AAH, Alzahrani MSA, Aldannish BH, et al. Inappropriate dental antibiotic prescriptions: potential driver of the antimicrobial resistance in Albaha region, Saudi Arabia. Risk Manag Healthc Policy 2020;13:175–82. 10.2147/RMHP.S247184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Alanazi MQ. An evaluation of community-acquired urinary tract infection and appropriateness of treatment in an emergency department in Saudi Arabia. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2018;14:2363–73. 10.2147/TCRM.S178855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Alanazi MQ, Al-Jeraisy MI, Salam M. Prevalence and predictors of antibiotic prescription errors in an emergency department, central Saudi Arabia. Drug Healthc Patient Saf 2015;7:103–11. 10.2147/DHPS.S83770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Alahdal AM, Elberry AA. Evaluation of applying drug dose adjustment by physicians in patients with renal impairment. Saudi Pharm J 2012;20:217–20. 10.1016/j.jsps.2011.12.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Al-Maliky GR, Al-Ward MM, Taqi A, et al. Evaluation of antibiotic prescribing for adult inpatients at Sultan Qaboos University Hospital, Sultanate of Oman. Eur J Hosp Pharm 2018;25:195–9. 10.1136/ejhpharm-2016-001146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Al-Yamani A, Khamis F, Al-Zakwani I, et al. Patterns of antimicrobial prescribing in a tertiary care hospital in Oman. Oman Med J 2016;31:35–9. 10.5001/omj.2016.07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Al-Hadithi D, Al-Zakwani I, Balkhair A, et al. Evaluation of the appropriateness of meropenem prescribing at a tertiary care hospital: a retrospective study in Oman. Int J Infect Dis 2020;96:180–6. 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.04.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Najdi AN, Khuffash FA, R'Shaid WA, et al. Antibiotic misuse in a paediatric teaching department in Kuwait. Ann Trop Paediatr 1988;8:145–8. 10.1080/02724936.1988.11748557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Khan FY, Elhiday A, Khudair IF, et al. Evaluation of the use of piperacillin/tazobactam (Tazocin) at Hamad General Hospital, Qatar: are there unjustified prescriptions? Infect Drug Resist 2012;5:17–21. 10.2147/IDR.S27965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Naeem D, Alshamrani MA, Aseeri MA, et al. Prescribing empiric antibiotics for febrile neutropenia: compliance with institutional febrile neutropenia guidelines. Pharmacy 2018;6:83. 10.3390/pharmacy6030083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. A Tolba YY, El-Kabbani AO, Al-Kayyali NS. An observational study of perioperative antibiotic-prophylaxis use at a major quaternary care and referral hospital in Saudi Arabia. Saudi J Anaesth 2018;12:82–8. 10.4103/sja.SJA_187_17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dib JG, Al-Tawfiq JA, Al Abdulmohsin S, et al. Improvement in vancomycin utilization in adults in a Saudi Arabian medical center using the Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee guidelines and simple educational activity. J Infect Public Health 2009;2:141–6. 10.1016/j.jiph.2009.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hammuda A, Hayder S, Elazzazy S, et al. Point prevalence survey of antimicrobial utilization in oncology patients. J Infect Dev Ctries 2013;7:990–3. 10.3855/jidc.3126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Aseeri MA. The impact of a pediatric antibiotic standard dosing table on dosing errors. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther 2013;18:220–6. 10.5863/1551-6776-18.3.220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Butt AA, Navasero CS, Thomas B, et al. Antibiotic prescription patterns for upper respiratory tract infections in the outpatient Qatari population in the private sector. Int J Infect Dis 2017;55:20–3. 10.1016/j.ijid.2016.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Brizzi MB, Burgos RM, Chiampas TD, et al. Impact of pharmacist-driven antiretroviral stewardship and transitions of care interventions on persons with human immunodeficiency virus. Open Forum Infect Dis 2020;7:ofaa073. 10.1093/ofid/ofaa073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Burns KW, Johnson KM, Pham SN, et al. Implementing outpatient antimicrobial stewardship in a primary care office through ambulatory care pharmacist-led audit and feedback. J Am Pharm Assoc 2020;60:e246–51. 10.1016/j.japh.2020.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Giruzzi ME, Tawwater JC, Grelle JL. Evaluation of antibiotic utilization in an emergency department after implementation of an antimicrobial stewardship pharmacist culture review service. Hosp Pharm 2020;55:261–7. 10.1177/0018578719844171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fay LN, Wolf LM, Brandt KL, et al. Pharmacist-led antimicrobial stewardship program in an urgent care setting. Am J Heal Pharm 2019;76:175–81. 10.1093/ajhp/zxy023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bessesen MT, Ma A, Clegg D, et al. Antimicrobial stewardship programs: comparison of a program with infectious diseases pharmacist support to a program with a geographic pharmacist staffing model. Hosp Pharm 2015;50:477–83. 10.1310/hpj5006-477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sadyrbaeva-Dolgova S, Aznarte-Padial P, Jimenez-Morales A, et al. Pharmacist recommendations for carbapenem de-escalation in urinary tract infection within an antimicrobial stewardship program. J Infect Public Health 2020;13:558–63. 10.1016/j.jiph.2019.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cappelletty D, Jacobs D. Evaluating the impact of a pharmacist’s absence from an antimicrobial stewardship team. Am J Heal Pharm 2013;70:1065–9. 10.2146/ajhp120482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Baker SN, Acquisto NM, Ashley ED, et al. Pharmacist-managed antimicrobial stewardship program for patients discharged from the emergency department. J Pharm Pract 2012;25:190–4. 10.1177/0897190011420160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Arensman K, Dela-Pena J, Miller JL, et al. Impact of mandatory infectious diseases consultation and real-time antimicrobial stewardship pharmacist intervention on Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia bundle adherence. Open Forum Infect Dis 2020;7:ofaa184. 10.1093/ofid/ofaa184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Apisarnthanarak A, Lapcharoen P, Vanichkul P, et al. Design and analysis of a pharmacist-enhanced antimicrobial stewardship program in Thailand. Am J Infect Control 2015;43:956–9. 10.1016/j.ajic.2015.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ohashi K, Matsuoka T, Shinoda Y, et al. Evaluation of treatment outcomes of patients with MRSA bacteremia following antimicrobial stewardship programs with pharmacist intervention. Int J Clin Pract 2018;72:e13065. 10.1111/ijcp.13065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Samura M, Hirose N, Kurata T, et al. Support for fungal infection treatment mediated by pharmacist-led antifungal stewardship activities. J Infect Chemother 2020;26:272–9. 10.1016/j.jiac.2019.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Haque A, Hussain K, Ibrahim R, et al. Impact of pharmacist-led antibiotic stewardship program in a PICU of low/middle-income country. BMJ Open Qual 2018;7:e000180–9. 10.1136/bmjoq-2017-000180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. MacMillan KM, MacInnis M, Fitzpatrick E, et al. Evaluation of a pharmacist-led antimicrobial stewardship service in a pediatric emergency department. Int J Clin Pharm 2019;41:1592–8. 10.1007/s11096-019-00924-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Buendía JA, Feliciano-Alfonso JE. Inappropriate antibiotic prescribing for acute bronchiolitis in Colombia: a predictive model. J Pharm Policy Pract 2021;14:2. 10.1186/s40545-020-00284-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Chua K-P, Linder JA. Prevalence of inappropriate antibiotic prescribing by antibiotic among privately and publicly insured non-elderly US patients, 2018. J Gen Intern Med 2020. 10.1007/s11606-020-06189-z. [Epub ahead of print: 01 Oct 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Amer MR, Akhras NS, Mahmood WA, et al. Antimicrobial stewardship program implementation in a medical intensive care unit at a tertiary care hospital in Saudi Arabia. Ann Saudi Med 2013;33:547–54. 10.5144/0256-4947.2013.547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Nasr Z, Babiker A, Elbasheer M, et al. Practice implications of an antimicrobial stewardship intervention in a tertiary care teaching hospital, Qatar. East Mediterr Health J 2019;25:172–80. 10.26719/emhj.18.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Enani MA. The antimicrobial stewardship program in Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states: insights from a regional survey. J Infect Prev 2016;17:16–20. 10.1177/1757177415611220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

ejhpharm-2021-002914supp001.pdf (133.6KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.