Abstract

Introduction

More than 700,000 COVID-19 cases have been linked to American colleges and universities since the beginning of the pandemic. However, studies are limited on the effects of the pandemic on college-aged young adults and its association with their COVID-19 vaccination status and intent.

Methods

Using the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey (HPS), a large, nationally representative survey fielded from April 14 through May 24, 2021, we assessed the effects of the pandemic (COVID-19 infection, mental health, food and financial security) on COVID-19 vaccination coverage (≥1 dose) and intentions toward vaccination among college-aged young adults in the United States (N = 6,758). We examined factors associated with vaccination coverage and intent, and reasons for not getting vaccinated.

Results

Approximately one-fifth (19.6%) of college-aged young adults had a previous diagnosis of COVID-19, 43.5% and 39.1% reported having anxiety or depression, respectively, 10.9% reported that they sometimes or often did not have enough food to eat, and 22.6% and 12.3% found it somewhat or very difficult, respectively, to pay for household expenses. Of college-aged young adults, 63.1% had received at least 1 dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, 15.4% probably would be vaccinated or were unsure about getting the vaccine, and 14.0% probably will not or definitely will not get vaccinated. Adults who were non-Hispanic Black (vs non-Hispanic White) or had food or financial insecurities (vs did not) were less likely to be vaccinated or intend to be vaccinated. Among adults who probably will not or definitely will not be vaccinated, more than one-third said that they did not believe a vaccine was needed.

Conclusion

Ensuring high and equitable vaccination coverage among college-aged young adults is critical for safely reopening in-person learning and resuming prepandemic activities.

Summary.

What is already known on this topic?

Since mid-2020, young adults have had the highest prevalence of COVID-19 cases and are least likely to be vaccinated or to intend to be vaccinated for COVID-19.

What is added by this report?

Approximately 63% of college-aged young adults had received at least 1 dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, 15.4% probably will or were unsure about getting the vaccine, and 14.0% probably will not or definitely will not get vaccinated. Students who were non-Hispanic Black or had food or financial insecurities were less likely than their counterparts to be vaccinated.

What are the implications for public health practice?

Ensuring high and equitable vaccination coverage is critical for safely reopening in-person learning as well as resuming prepandemic activities.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in disruptions to the lives and education of college students (1,2). Because of college lockdowns, cancellation of classes, social distancing recommendations, and shifts in instructional methods, most college students have experienced changes to their daily lives, including quarantining or living at home, having mental health issues, experiencing housing and food insecurity, and having financial hardships (3–9). A recent survey found that more than 700,000 COVID-19 cases have been linked to American colleges and universities since the beginning of the pandemic (10). Since mid-2020, the highest prevalence of COVID-19 cases has been among young adults (adults aged 18–24, followed by those aged 25–34) (11,12). Young adults feel less at risk than older adults for the consequences of COVID-19 and are less likely to adhere to strategies to minimize risk of exposure to COVID-19, such as mask wearing or social distancing (13). Because young adults are less likely to adhere to mitigation strategies, they are more likely to spread the SARS-CoV-2 virus to others and are at risk of COVID-19–related morbidity and mortality (12,13).

Although the COVID-19 vaccine is available now to everyone 12 years or older, young adults have been less likely than older adults to get vaccinated or intend to get vaccinated (14,15). Vaccination administration data reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) from December 14, 2020, to May 22, 2021, indicated that young adults (adults aged 18–29 and 30–49) had lower vaccination rates (38% and 49%, respectively) than adults aged 65 or older (79%) (14). Furthermore, a national survey found that 23% of adults aged 18 to 39 reported that they would probably get or were unsure about getting a COVID-19 vaccine, and 24% reported that they would probably not or would definitely not get vaccinated (15). Studies found that although college students were more likely to get a COVID-19 vaccine than an influenza vaccine, students perceived that other young adults would be less likely to be vaccinated for COVID-19 and would not think vaccination was as important (16,17). These studies suggest that developing and testing norms-based intervention strategies, such as personalized normative feedback, would increase COVID-19 vaccination among college students.

We used the Health Belief Model to conceptualize mental health status, food and financial insecurity, and sociodemographic factors as barriers to vaccination, and prior COVID-19 infection as related to perceived risk in a model to understand factors associated with COVID-19 vaccination and intent (18). Understanding barriers and perceived risk among college-age students and their association with COVID-19 vaccination status and intent is needed to tailor messages to increase vaccine uptake in this population. The objective of this study was to examine state and national estimates of, and factors associated with, COVID-19 vaccination coverage and intent. Furthermore, we assessed reasons for not vaccinating among a large, national sample of college-aged young adults.

Methods

This study used data from the Household Pulse Survey (HPS), a large, nationally representative household survey conducted by the US Census Bureau since April 2020 to help understand household experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. The design of this survey is described elsewhere (19–21). The survey is fielded once or twice per month with approximately 75,000 respondents during each wave. We combined data from 3 survey waves (April 14–April 26, April 28–May 10, and May 12–24, 2021) for this study; response rates ranged from 6.6% to 7.4% (22). This study was reviewed by the Tufts University Health Sciences Institutional Review Board and was considered not to be human subjects research.

College-aged young adults

Respondents were asked “What is the highest degree or level of school you have completed?” and “How many members of your household, including yourself, are currently taking, or were planning to take classes this term from a college, university, community college, trade school, or other occupational school (such as a cosmetology school or a school of culinary arts)?” Respondents who answered “some college, but degree not received or is in progress” to the former question and one or more to the latter question were categorized as college-aged young adults to reduce the potential for misclassification if they were not in fact college students. To further reduce potential for misclassification (ie, if a respondent had some college education, but was not currently in college and had someone else in the household, such as children, in college), the analysis was restricted to respondents aged 39 or younger (n = 6,803).

COVID-19 questions

The HPS asks questions on COVID-19 diagnosis and vaccination coverage, intent, and reasons for not vaccinating. COVID-19 diagnosis was assessed by the following question: “Has a doctor or other health care provider ever told you that you have COVID-19?” (yes/no/not sure). COVID-19 vaccination receipt (≥1 dose) was assessed with the following question: “Have you received a COVID-19 vaccine?” (yes/no). People who did not answer the question about whether they had been vaccinated were excluded from the analysis (n = 45). Among unvaccinated adults, intent to be vaccinated was assessed with the following question: “Once a vaccine to prevent COVID-19 is available to you, would you . . . definitely, probably, be unsure about, probably not, or definitely not get(ting) a vaccine.” Because the vaccination intent questions were asked only of those who were not vaccinated, assessing intent over time would show bias as more people got vaccinated (reducing the sample size of those who are asked about intent). To reduce this potential for bias, the denominator for vaccination intent was everyone in the sample, including those who were vaccinated. Unvaccinated respondents who did not definitely plan to be vaccinated were categorized as 1) probably will get vaccinated/unsure about getting vaccinated and 2) probably will not/definitely will not get vaccinated.

Among nonvaccinated individuals who definitely did not intend to get vaccinated, respondents were asked reasons for not getting vaccinated: “Which of the following, if any, are reasons that you [probably will/be unsure about/probably won’t/definitely won’t] get a COVID-19 vaccine?” Response options, in which they could select all that apply, were: 1) I am concerned about possible side effects of a COVID-19 vaccine, 2) I don’t know if a COVID-19 vaccine will work, 3) I don’t believe I need a COVID-19 vaccine, 4) I don’t like vaccines, 5) My doctor has not recommended it, 6) I plan to wait and see if it is safe and may get it later, 7) I think other people need it more than I do right now, 8) I am concerned about the cost of a COVID-19 vaccine, 9) I don’t trust COVID-19 vaccines, 10) I don’t trust the government, and 11) other. These questions underwent expert review at the US Census Bureau and federal partner agencies, as well as cognitive testing in laboratories at CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics (20).

Sociodemographic variables

Sociodemographic variables assessed were age group (18–24, 25–29, 30–34, and 35–39 y), sex (female, male), and race and ethnicity (Hispanic, non-Hispanic Asian, non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic other/multiple races, and non-Hispanic White).

Food and financial security

Food sufficiency was assessed through the following question: “Getting enough food can also be a problem for some people. In the last 7 days, which of these statements best describes the food eaten in your household?” This variable was categorized as 1) having enough food to eat in the past 7 days, regardless of whether the food is always the kind of food that the respondent wanted to eat, and 2) sometimes or often not having enough to eat. Financial security was assessed through the following question: “In the last 7 days, how difficult has it been for your household to pay for usual household expenses, including but not limited to food, rent or mortgage, car payments, medical expenses, student loans, and so on?” Responses were categorized as “very,” “somewhat,” “a little,” and “not at all.”

Mental health questions

Questions about anxiety and depression were modified from a validated 2-item Patient Health Questionnaire–2 (PHQ–2) and the 2-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD–2) scale (23,24) (Box). Responses to both scales were assigned a numerical value ranging from 0 to 3 (not at all = 0, several days = 1, more than half the days = 2, and nearly every day = 3). Scores from each scale were summed; a score of ≥3 on the PHQ–2 was categorized as symptoms of depression (hereinafter referred to as depression), and a sum of ≥3 on the GAD–2 was categorized as symptoms of anxiety (hereinafter referred to as anxiety).

Box. Questions Adapted from Patient Health Questionnaire–2 and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (23,24).

Patient Health Questionnaire–2

1) “Over the last 7 days, how often have you been bothered by . . . having little interest or pleasure in doing things? Would you say not at all, several days, more than half the days, or nearly every day?”

2) “Over the last 7 days, how often have you been bothered by . . . feeling down, depressed, or hopeless? Would you say not at all, several days, more than half the days, or nearly every day?”

Generalized Anxiety Disorder–2 Scale

1) “Over the last 7 days, how often have you been bothered by the following problems . . . Feeling nervous, anxious, or on edge? Would you say not at all, several days, more than half the days, or nearly every day?”

2) “Over the last 7 days, how often have you been bothered by the following problems . . . Not being able to stop or control worrying? Would you say not at all, several days, more than half the days, or nearly every day?

Analysis

Prevalence of COVID-19 diagnosis, food and financial insecurity, and mental health conditions were assessed overall and by vaccination coverage (≥1 dose) and intent to be vaccinated (probably will get vaccinated/unsure about getting vaccinated or probably will not/definitely will not) among college-aged young adults aged 39 or younger. We conducted multivariable regression models to examine factors associated with at least 1 dose of COVID-19 vaccine receipt and intent. We examined proportions and 95% CIs for reasons for not getting vaccinated among adults who were probably or unsure about getting vaccinated and probably will not or definitely will not be vaccinated. Contrast tests for the differences in proportions, comparing each category to the referent category, were conducted with a .05 significance level (α = .05). Analyses accounted for the survey design and weights to ensure the sample was representative of the US population by using Stata version 16.1 (StataCorp LLC).

Results

Approximately one-half (47.4%) of adults in this sample were aged 18 to 24, 20.2% were aged 25 to 29, 18.2% were aged 30 to 34, and 14.2% were aged 35 to 39 years. By race and ethnicity, 54.8% were non-Hispanic White, 23.2% were Hispanic, 12.1% were non-Hispanic Black, 5.2% were non-Hispanic Asian, and 4.7% were non-Hispanic other/multiple races (Table 1). Moreover, 10.9% reported that they sometimes or often did not have enough food to eat in the past 7 days, and 22.6% and 12.3% reported that it was somewhat or very difficult, respectively, to pay for household expenses in the past 7 days. More than one-third reported having anxiety (43.5%) or depression (39.1%) in the past 7 days, and 19.6% reported a previous diagnosis of COVID-19.

Table 1. Characteristics of College Students, Household Pulse Survey, US, April 14–May 24, 2021a .

| Characteristic | Overall |

Previous COVID-19 Diagnosis, % (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unweighted n | % (95% CI) | ||

| All adults aged 18–39 | 6,758 | 100 | 19.6 (17.9–21.5) |

| Age group, y | |||

| 18–24 | 2,327 | 47.4 (45.7–49.2) | 20.9 (18.5–23.6) |

| 25–29 | 1,277 | 20.2 (18.7–21.8) | 21.0 (17.5–25.0) |

| 30–34 | 1,505 | 18.2 (16.9–19.6) | 16.4 (13.5–19.6) |

| 35–39 | 1,649 | 14.2 (13.2–15.2) | 17.6 (14.8–20.7) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 2,670 | 47.5 (46.3–48.6) | 18.9 (16.3–21.7) |

| Female | 4,088 | 52.5 (51.4–53.7) | 20.3 (18.4–22.4) |

| Race and ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic | 1,269 | 23.2 (22.0–24.5) | 25.8 (21.8–30.2) |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 334 | 5.2 (4.6–6.0) | 13.3 (8.5–20.4) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 748 | 12.1 (11.0–13.2) | 16.7 (13.4–20.8) |

| Non-Hispanic other/multiple races | 427 | 4.7 (4.2–5.3) | 12.8 (9.1–17.7) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 3,980 | 54.8 (53.4–56.1) | 18.9 (16.7–21.3) |

| Food sufficiency | |||

| Sometimes/often not enough to eat | 592 | 10.9 (9.6–12.4) | 19.9 (14.6–26.6) |

| Enough food to eat | 4,136 | 89.1 (87.6–90.4) | 18.2 (16.4–20.3) |

| Difficulty paying for household expenses | |||

| Not at all difficult | 1,982 | 34.8 (32.8–36.9) | 17.0 (14.7–19.6) |

| A little difficult | 1,689 | 30.3 (28.4–32.3) | 18.3 (15.5–21.6) |

| Somewhat difficult | 1,314 | 22.6 (20.9–24.4) | 19.5 (15.9–23.6) |

| Very difficult | 882 | 12.3 (11.1–13.6) | 21.8 (17.7–26.6) |

| Anxiety | |||

| Yes | 1,705 | 43.5 (41.1–45.9) | 19.2 (16.0–23.0) |

| No | 2,155 | 56.5 (54.1–58.9) | 17.8 (15.1–20.8) |

| Depression | |||

| Yes | 1,444 | 39.1 (36.7–41.5) | 19.2 (15.6–23.3) |

| No | 2,416 | 60.9 (58.5–63.3) | 18.0 (15.5–20.7) |

All estimates were weighted to be representative of the US population.

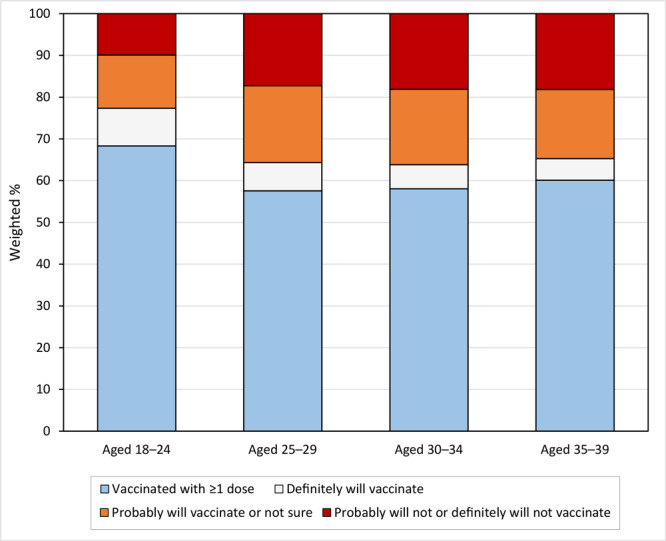

Approximately 63% of college-aged young adults in this sample had received at least 1 dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, 15.4% reported that they probably would be vaccinated or were unsure about getting the vaccine, and 14.0% reported that they probably will not or definitely will not get vaccinated (Table 2). Vaccination coverage ranged from 42.8% in Mississippi to 83.5% in Vermont (Figure 1). By age, vaccination coverage was higher among adults aged 18 to 24 (68.3%) than among adults aged 25 to 29 (57.6%), 30 to 34 (58.1%), and 35 to 39 (60.1%) (Table 2 and Figure 2).

Table 2. Prevalence of and Factors Associated With COVID-19 Vaccination (≥1 Dose) and Intent to Get Vaccinated, Household Pulse Survey, US, April 14–May 24, 2021.

| Characteristic | COVID-19 Vaccination (≥1 Dose) |

COVID-19 Vaccination Intent |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Probably Will/Unsure About Getting the Vaccine |

Definitely or Probably Will Not Get the Vaccine |

|||||

| % (95% CI) | aPR (95% CI)a | % (95% CI) | aPR (95% CI)a | % (95% CI) | aPR (95% CI)a | |

| All | 63.1 (60.9–65.3) | — | 15.4 (13.9–17.0) | — | 14.0 (12.9–15.3) | — |

| Age group, y | ||||||

| 18–24 | 68.3 (65.0–71.5) | 1 [Reference] | 12.8 (11.0–14.7) | 1 [Reference] | 9.9 (8.4–11.7) | 1 [Reference] |

| 25–29 | 57.6 (53.2–61.8)b | 0.93 (0.84–1.03) | 18.4 (14.8–22.8)b | 1.06 (0.77–1.46) | 17.2 (14.2–20.8)b | 1.71 (1.21–2.42) |

| 30–34 | 58.1 (54.2–61.9)b | 0.94 (0.86–1.03) | 18.0 (15.7–20.7)b | 1.16 (0.87–1.54) | 18.1 (15.3–21.4)b | 1.61 (1.17–2.22) |

| 35–39 | 60.1 (56.2–63.9)b | 0.93 (0.84–1.03) | 16.6 (14.2–19.3)b | 1.24 (0.97–1.59) | 18.2 (15.7–20.9)b | 1.45 (1.04–2.02) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 63.1 (59.6–66.5) | 1.00 (0.93–1.07) | 16.1 (13.7–18.8) | 1.10 (0.88–1.38) | 13.2 (11.5–15.1) | 0.91 (0.73–1.14) |

| Female | 63.1 (60.8–65.4) | 1 [Reference] | 14.8 (13.1–16.8) | 1 [Reference] | 14.8 (13.3–16.5) | 1 [Reference] |

| Race and ethnicity | ||||||

| Hispanic | 66.9 (62.2–71.3) | 1.05 (0.96–1.15) | 16.8 (13.6–20.6) | 1.17 (0.83–1.66) | 8.1 (6.3–10.3)b | 0.57 (0.40–0.82) |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 84.4 (79.6–88.3)b | 1.33 (1.22–1.44) | 4.6 (2.7–7.7)b | 0.38 (0.17–0.83) | —c | 0.04 (0.004–0.29) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 42.7 (36.8–48.8)b | 0.69 (0.59–0.82) | 27.0 (22.0–32.3)b | 1.95 (1.44–2.63) | 20.6 (17.0–24.8) | 0.97 (0.75–1.25) |

| Non-Hispanic other/multiple races | 65.0 (58.2–71.1) | 1.06 (0.94–1.21) | 12.8 (8.9–18.2) | 0.79 (0.49–1.27) | 13.3 (9.5–18.3) | 0.62 (0.34–1.11) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 63.8 (61.3–66.3) | 1 [Reference] | 13.5 (11.9–15.3) | 1 [Reference] | 16.4 (14.7–18.2) | 1 [Reference] |

| Food sufficiency | ||||||

| Sometimes/often not enough to eat | 46.2 (38.8–53.7)b | 0.83 (0.70–0.98) | 23.8 (18.5–30.1)b | 1.40 (1.00–1.96) | 24.2 (18.9–30.6)b | 1.34 (0.98–1.82) |

| Enough food to eat | 65.5 (62.9–68.1) | 1 [Reference] | 13.9 (12.2–15.7) | 1 [Reference] | 12.8 (11.5–14.1) | 1 [Reference] |

| Difficulty paying for household expenses | ||||||

| Not at all difficult | 70.8 (67.0–74.2) | 1 [Reference] | 12.0 (9.9–14.6) | 1 [Reference] | 10.1 (8.2–12.4) | 1 [Reference] |

| A little difficult | 66.1 (62.6–69.4)b | 0.94 (0.87–1.01) | 13.7 (11.2–16.7) | 1.20 (0.90–1.60) | 11.9 (10.1–14.1) | 1.16 (0.84–1.62) |

| Somewhat difficult | 61.6 (57.4–65.6)b | 0.93 (0.83–1.04) | 18.4 (15.4–21.7)b | 1.30 (0.97–1.73) | 14.2 (11.5–17.4)b | 1.45 (0.92–2.28) |

| Very difficult | 45.9 (40.4–51.5)b | 0.71 (0.62–0.82) | 21.4 (17.4–26.1)b | 1.51 (1.09–2.09) | 25.1 (20.4–30.4)b | 2.24 (1.53–3.27) |

| Anxiety | ||||||

| Yes | 63.2 (59.5–66.7) | 1.06 (0.97–1.16) | 15.3 (12.4–18.8) | 0.97 (0.72–1.31) | 13.2 (11.2–15.5) | 0.78 (0.61–1.00) |

| No | 64.9 (61.6–68.1) | 1 [Reference] | 14.4 (12.4–16.6) | 1 [Reference] | 14.1 (12.3–16.2) | 1 [Reference] |

| Depression | ||||||

| Yes | 62.7 (58.5–66.7) | 0.99 (0.91–1.08) | 15.1 (11.9–18.9) | 0.93 (0.69–1.25) | 12.4 (10.2–15.0) | 0.77 (0.58–1.02) |

| No | 65.1 (62.0–68.1) | 1 [Reference] | 14.6 (12.5–17.0) | 1 [Reference] | 14.5 (12.6–16.6) | 1 [Reference] |

| Previous COVID-19 diagnosis | ||||||

| Yes | 56.1 (50.9–61.2)b | 0.91 (0.81–1.01) | 20.6 (17.3–24.3)b | 1.49 (1.14–1.94) | 15.0 (12.1–18.4) | 0.88 (0.69–1.14) |

| No | 65.1 (62.8–67.3) | 1 [Reference] | 13.8 (12.3–15.5) | 1 [Reference] | 13.9 (12.7–15.2) | 1 [Reference] |

Abbreviation: aPR, adjusted prevalence ratio.

aPR adjusted for age, sex, race or ethnicity, previous COVID-19 diagnosis, anxiety or depressive status, current food sufficiency, and difficulty paying for household expenses. All proportions and adjusted prevalence ratios were weighted to be representative of the US population.

Significant difference (P < .05) in proportions between group specified and referent group; determined by contrast tests for proportions.

Estimates were suppressed because of relative standard error >30%.

Figure 1.

COVID-19 vaccination coverage and intention to vaccinate among college students by state, US, Household Pulse Survey, April 14–May 24, 2021.

| State | Vaccinated With 1 or More Doses, % | Definitely Will Vaccinate, % | Probably Will Vaccinate or Not Sure, % | Probably Will Not or Definitely Will Not Vaccinate, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mississippi | 42 | 3 | 20 | 35 |

| Idaho | 44 | 7 | 31 | 18 |

| Tennessee | 49 | 4 | 21 | 26 |

| West Virginia | 50 | 12 | 18 | 20 |

| North Dakota | 52 | 4 | 5 | 38 |

| Louisiana | 53 | 9 | 27 | 10 |

| Florida | 53 | 5 | 22 | 21 |

| Alabama | 53 | 11 | 17 | 19 |

| South Carolina | 54 | 5 | 21 | 21 |

| Georgia | 54 | 10 | 16 | 20 |

| Iowa | 55 | 9 | 12 | 23 |

| Arkansas | 56 | 7 | 17 | 19 |

| Wyoming | 56 | 7 | 14 | 23 |

| Oklahoma | 56 | 5 | 13 | 26 |

| North Carolina | 58 | 8 | 18 | 16 |

| New Jersey | 59 | 16 | 17 | 9 |

| Michigan | 60 | 5 | 22 | 12 |

| Pennsylvania | 61 | 10 | 16 | 13 |

| Illinois | 61 | 12 | 15 | 12 |

| Washington | 62 | 11 | 12 | 16 |

| South Dakota | 62 | 6 | 16 | 17 |

| Indiana | 62 | 8 | 14 | 15 |

| Oregon | 62 | 5 | 18 | 15 |

| Utah | 63 | 7 | 13 | 17 |

| Maine | 64 | 10 | 13 | 14 |

| Kentucky | 64 | 4 | 12 | 20 |

| Texas | 64 | 4 | 17 | 15 |

| New Hampshire | 65 | 14 | 9 | 12 |

| Ohio | 65 | 3 | 20 | 12 |

| Missouri | 65 | 3 | 17 | 16 |

| Maryland | 66 | 7 | 19 | 8 |

| New York | 67 | 6 | 15 | 12 |

| District of Columbia | 68 | 5 | 16 | 12 |

| Virginia | 68 | 5 | 11 | 16 |

| Nevada | 68 | 4 | 11 | 16 |

| California | 69 | 11 | 11 | 9 |

| Minnesota | 69 | 13 | 11 | 8 |

| Colorado | 69 | 8 | 13 | 10 |

| Rhode Island | 69 | 6 | 15 | 10 |

| Arizona | 70 | 5 | 12 | 14 |

| Nebraska | 70 | 6 | 12 | 13 |

| Massachusetts | 71 | 6 | 15 | 8 |

| Alaska | 71 | 4 | 12 | 13 |

| Connecticut | 71 | 6 | 13 | 10 |

| New Mexico | 71 | 5 | 12 | 13 |

| Kansas | 72 | 2 | 9 | 17 |

| Wisconsin | 73 | 6 | 9 | 13 |

| Hawaii | 76 | 6 | 10 | 8 |

| Delaware | 76 | 2 | 14 | 8 |

| Montana | 77 | 0 | 9 | 15 |

| Vermont | 84 | 3 | 3 | 11 |

Figure 2.

COVID-19 vaccination coverage and intention to vaccinate among college students by age group, US, Household Pulse Survey, April 14 –May 24, 2021.

| Age Group, y | Vaccinated With 1 or More Doses, % | Definitely Will Vaccinate, % | Probably Will Vaccinate or Not Sure, % | Probably Will Not or Definitely Will Not Vaccinate, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18–24 | 68 | 9 | 13 | 10 |

| 25–29 | 58 | 7 | 18 | 17 |

| 30–34 | 58 | 6 | 18 | 18 |

| 35–39 | 60 | 5 | 17 | 18 |

By race and ethnicity (Table 2), vaccination coverage was highest among non-Hispanic Asian students (84.4%), followed by Hispanic students (66.9%), non-Hispanic other/multiple races (65.0%), non-Hispanic White (63.8%), and non-Hispanic Black (42.7%). Non-Hispanic Black students (adjusted prevalence ratio [aPR], 0.69; 95% CI, 0.59–0.82), students who sometimes or often did not have enough to eat (aPR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.70–0.98), and those who found it very difficult to pay for household expenses (aPR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.62–0.82) were less likely than their counterparts to be vaccinated. Among unvaccinated young adults, those who were non-Hispanic Black (aPR, 1.95; 95% CI, 1.44–2.63), found it very difficult to pay for household expenses (aPR, 1.51; 95% CI, 1.09–2.09), or had a previous diagnosis of COVID-19 (aPR, 1.49; 95% CI, 1.14–1.94) were more likely than their counterparts to report that they probably would get vaccinated or that they were unsure about vaccination (Table 2). Furthermore, adults aged 25 to 29 were more likely than those aged 18 to 24 to report that they did not intend to be vaccinated (aPR, 1.71; 95% CI, 1.21–2.42). Those who often or sometimes did not have enough to eat (aPR, 1.34; 95% CI, 0.98–1.82) and those who found it very difficult to pay for household expenses (aPR, 2.24; 95% CI, 1.53–3.27) were more likely than their counterparts to report that they probably would not or definitely would not get vaccinated.

Among students who would probably get vaccinated or are unsure, the main reasons for not getting vaccinated were the desire to wait and see if it is safe and may get it later (65.3%), concern about possible side effects (59.9%), and the belief that other people need it more right now (35.3%) (Table 3). Among students who reported that they probably will not or definitely will not be vaccinated, reasons for not wanting to be vaccinated were concern about possible side effects (55.0%), lack of trust in COVID-19 vaccines (50.7%), waiting to see if it is safe (41.0%), lack of trust in the government (40.7%), and belief that a vaccine is not needed (39.3%).

Table 3. Reasons for Not Getting Vaccinated, by COVID-19 Vaccination Intent, Household Pulse Survey, US, April 14–May 24, 2021a .

| Reason | COVID-19 Vaccination Intent |

|

|---|---|---|

| Probably Will/Unsure About Getting the Vaccine, % (95% CI) | Definitely or Probably Will Not Get the Vaccine, % (95% CI) | |

| Plan to wait and see if it is safe and may get it later | 65.3 (60.7–69.8) | 41.0 (36.6–45.4) |

| Concerned about possible side effects | 59.9 (55.7–64.0) | 55.0 (51.1–59.0) |

| Other people need it more right now | 35.3 (30.6–40.0) | 16.2 (12.6–19.9) |

| Don’t trust the government | 18.1 (14.6–21.7) | 40.7 (36.5–44.9) |

| Don’t know if a vaccine will work | 17.5 (13.4–21.7) | 24.4 (20.3–28.4) |

| Don’t trust COVID-19 vaccines | 16.1 (12.6–19.6) | 50.7 (46.8–54.6) |

| Don’t believe I need a vaccine | 13.8 (10.3–18.3) | 39.3 (34.2–44.7) |

| Don’t like vaccines | 8.1 (5.4–10.8) | 16.2 (12.3–20.2) |

| Concerned about the cost | 6.5 (3.3–9.6) | 5.1 (2.2–8.0) |

| Doctor has not recommended it | 4.8 (2.9–6.7) | 7.5 (4.9–10.1) |

| Other reason for not getting vaccine | 9.3 (7.2–11.4) | 14.3 (11.3–17.3) |

All proportions were weighted to be representative of the US population.

Discussion

We found that nearly 1 in 5 college-aged young adults had been diagnosed with COVID-19, yet 36.9% had not been vaccinated, and 14.0% reported that they probably will not or definitely will not get vaccinated. These findings are concerning, because many college campuses returned to in-person classes in fall 2021, and some colleges do not have vaccination requirements (25). Furthermore, COVID-19 vaccination coverage among US college students varies widely, and some states, particularly those in the South, that have lower coverage and a higher proportion of the population who do not intend to get vaccinated, may increase risk for COVID-19 transmission.

Vaccination coverage among our study population was higher than that found among a nationally representative sample of young adults (15), suggesting that this group may be more responsive to COVID-19 vaccinations than other young adults. However, high vaccination coverage, among all students, is needed for herd immunity. Our study found that college-aged young adults aged 25 or older were less likely than those aged 18 to 24 to get vaccinated, which is in contrast to other studies that found higher vaccination rates among older adults compared with younger adults (14,15). This finding may be due to younger students being more likely to live on campus and get vaccinated because of their close living quarters than older students who may be living off campus or at home. We also found that those who were non-Hispanic Black were least likely among the racial and ethnic groups studied to have been vaccinated and those most likely to have been vaccinated were non-Hispanic Asian, findings that are consistent with other studies (14,15).

The main reasons for not getting vaccinated were waiting to see if the vaccine is safe and concerns about possible side effects. However, among students who probably will not or definitely will not get vaccinated, more than one-half reported that they did not trust COVID-19 vaccines, and about 40% reported that they did not trust the government or believe that they needed a vaccine. This finding is consistent with other studies that found college students to be hesitant toward other vaccines, such as for influenza and human papillomavirus (26,27). Sharing clear and consistent messages about COVID-19 vaccines, increasing confidence in vaccine safety and effectiveness, and highlighting vaccines as important for resuming social activities are important for achieving high vaccination coverage and protecting this population from COVID-19. Furthermore, promoting vaccines on campus and making vaccinations easily accessible to students, such as at student health clinics, may increase vaccination uptake.

Our findings that 43.5% of college-aged young adults reported having anxiety, 39.1% reported depression, 10.9% expressed that they sometimes or often did not have sufficient food, and 34.9% had some or a lot of difficulty covering household expenses highlights the vulnerability of this population and the importance of reducing further adverse health outcomes. Although our study found that college-aged young adults had lower food insufficiency rates than the general population (9), they still experienced vulnerabilities such as anxiety, depression, and financial instability. Vulnerable groups may be less likely to be vaccinated or intend to be vaccinated, and if combined with other comorbidities, this lack of vaccination may increase their risk for serious effects from COVID-19 (28). Some groups, such as non-Hispanic Black adults, may face barriers to vaccination (15). Ensuring high and equitable vaccination coverage among all students is needed to curb the transmission of COVID-19 among students and their families, friends, and communities.

This study has several potential limitations. First, although sampling methods and data weighting were designed to produce nationally representative results, respondents might not be fully representative of the general US adult population (29). Second, the HPS has a low response rate (<10%); however, a nonresponse bias assessment conducted by the US Census Bureau found that the survey weights adjusted for most of this bias, even though some bias may remain (29). Third, vaccination status was self-reported and is subject to social desirability bias. Fourth, although the study attempted to capture college students in this sample, misclassification may have occurred if respondents received some college education and lived with someone else in the household who is currently in college. Fifth, dates of COVID-19 infection and vaccination were not available to assess temporal relationships of these events. Finally, state-level vaccination estimates represent estimates in the state in which college-aged young adults currently live. Because many students may have lived at home during the pandemic, these estimates may not reflect coverage in states in which students go to school.

Vaccination mandates may be useful in increasing vaccination rates among college-aged young adults: previous studies have shown success in improving other childhood vaccination rates (30,31). However, states differ in their legal ability to require COVID-19 vaccinations, the stringency and enforcement of mandates, and the ethical concerns about mandates (32–34). Although an increasing number of colleges are requiring COVID-19 vaccines, many colleges have not implemented mandates. Our study shows that disparities still exist in vaccination coverage and intent among college-aged young adults. In addition to mandates, several studies found that encouraging vaccination for the greater good and making vaccines easily accessible to students may be strong motivators for vaccination (16,17). Emphasizing that COVID-19 vaccines are important for preventing transmission of COVID-19 to family and friends and removing barriers to vaccination are needed to safely reopen in-person learning as well as to resume prepandemic activities.

Acknowledgments

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose. None of the authors have financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose. No funding was secured for this study. Jennifer D. Allen was supported by the Tufts University Office of the Vice Provost for Research, Research and Scholarship Strategic Plan. Laura Corlin was supported by Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development grant number K12HD092535 and by the Tufts University/Tufts Medical Center COVID-19 Rapid Response Seed Funding Program. No copyrighted materials were used.

Footnotes

The opinions expressed by authors contributing to this journal do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the Public Health Service, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or the authors' affiliated institutions.

Suggested citation for this article: Nguyen KH, Irvine S, Epstein R, Allen JD, Corlin L. Prior COVID-19 Infection, Mental Health, Food and Financial Insecurity, and Association With COVID-19 Vaccination Coverage and Intent Among College-Aged Young Adults, US, 2021. Prev Chronic Dis 2021;18:210260. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd18.210260.

References

- 1. Zhai Y, Du X. Addressing collegiate mental health amid COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res 2020;288:113003. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lederer AM, Hoban MT, Lipson SK, Zhou S, Eisenberg D. More than inconvenienced: the unique needs of US college students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Educ Behav 2021;48(1):14–9. http:// 10.1177/1090198120969372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Duong V, Luo J, Pham P, Yang T, Wang Y. The ivory tower lost: how college students respond differently than the general public to the COVID-19 pandemic. Paper presented at: 2020 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining; December 7–10, 2020; Virtual. https://web.ntpu.edu.tw/~myday/doc/ASONAM2020/ASONAM2020_Proceedings/pdf/papers/021_041_126.pdf. Accessed April 25, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wang X, Hegde S, Son C, Keller B, Smith A, Sasangohar F. Investigating mental health of US college students during the COVID-19 pandemic: cross-sectional survey study. J Med Internet Res 2020;22(9):e22817. 10.2196/22817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mialki K, House LA, Mathews AE, Shelnutt KP. COVID-19 and college students: food security status before and after the onset of a pandemic. Nutrients 2021;13(2):628. 10.3390/nu13020628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Owens MR, Brito-Silva F, Kirkland T, Moore CE, Davis KE, Patterson MA, et al. Prevalence and social determinants of food insecurity among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nutrients 2020;12(9):2515. 10.3390/nu12092515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sahu P. Closure of universities due to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): impact on education and mental health of students and academic staff. Cureus 2020;12(4):e7541. 10.7759/cureus.7541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. US Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Policy Development and Research. Insights into housing and community development policy: barriers to success: housing insecurity for US college students. 2015. https://www.huduser.gov/portal/periodicals/insight/insight_2.pdf. Accessed May 11, 2021.

- 9. Gundersen C. Are college students more likely to be food insecure than nonstudents of similar ages? Appl Econ Perspect Policy 2020:aepp.13110. 10.1002/aepp.13110 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cai W, Ivory D, Semple K, Smith M, Lemonides A, Higgins L, et al. Tracking coronavirus cases at US colleges and universities. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/us/college-covid-tracker.html. Accessed May 20, 2021.

- 11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19 weekly cases and deaths per 100,000 population by age, race/ethnicity, and sex. https://Covid.Cdc.Gov/Covid-Data-Tracker/#Demographicsovertime. Accessed July 1, 2021.

- 12. Boehmer TK, DeVies J, Caruso E, van Santen KL, Tang S, Black CL, et al. Changing age distribution of the COVID-19 pandemic — United States, May–August 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69(39):1404–9. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6939e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hutchins HJ, Wolff B, Leeb R, Ko JY, Odom E, Willey J, et al. COVID-19 mitigation behaviors by age group — United States, April–June 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69(43):1584–90. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6943e4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Diesel J, Sterrett N, Dasgupta S, Kriss JL, Barry V, Vanden Esschert K, et al. COVID-19 vaccination coverage among adults — United States, December 14, 2020–May 22, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021;70(25):922–7. 10.15585/mmwr.mm7025e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Baack BN, Abad N, Yankey D, Kahn KE, Razzaghi H, Brookmeyer K, et al. COVID-19 vaccination coverage and intent among adults aged 18–39 years — United States, March–May 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021;70(25):928–33. 10.15585/mmwr.mm7025e2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Graupensperger S, Abdallah DA, Lee CM. Social norms and vaccine uptake: college students’ COVID vaccination intentions, attitudes, and estimated peer norms and comparisons with influenza vaccine. Vaccine 2021;39(15):2060–7. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.03.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sinclair S, Agerström J. Do social norms influence young people’s willingness to take the COVID-19 vaccine? Health Commun 2021:1–8. 10.1080/10410236.2021.1937832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Champion VL, Skinner CS. The health belief model. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K, editors. Health behavior and health education: theory, research, and practice. 4th edition. Jossey-Bass; 2008. p.45–65. [Google Scholar]

- 19. US Census Bureau. Measuring household experiences during the coronavirus pandemic. https://www.census.gov/data/experimental-data-products/household-pulse-survey.html. Accessed June 3, 2021.

- 20. Fields JF, Hunter-Childs J, Tersine A, Sisson J, Parker E, Velkoff V, et al. 2020 Household Pulse Survey, 2020. US Census Bureau. https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/demo/technical-documentation/hhp/2020_HPS_Background.pdf. Accessed April 2, 2021.

- 21. Nguyen KH, Nguyen KC, Corlin L, Allen J, Chung M. Changes in receipt of COVID-19 vaccination and intention to vaccinate, by socioeconomic characteristics and geographic area, adults ≥18 years, United States, January 6–March 29, 2021. Ann Med 2021;53(1):1419–28. 10.1080/07853890.2021.1957998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. US Census Bureau. Source of the data and accuracy of the estimate for the Household Pulse Survey — phase 3. https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/demo/technical-documentation/hhp/Phase3-1_Source_and_Accuracy_Week_30.pdf. Accessed April 15, 2021.

- 23. Arroll B, Goodyear-Smith F, Crengle S, Gunn J, Kerse N, Fishman T, et al. Validation of PHQ-2 and PHQ-9 to screen for major depression in the primary care population. Ann Fam Med 2010;8(4):348–53. 10.1370/afm.1139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Plummer F, Manea L, Trepel D, McMillan D. Screening for anxiety disorders with the GAD-7 and GAD-2: a systematic review and diagnostic metaanalysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2016;39:24–31. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2015.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Thomason A, O’Leary B. Here’s a list of colleges that will require students or employees to be vaccinated against COVID-19. The Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/blogs/live-coronavirus-updates/heres-a-list-of-colleges-that-will-require-students-to-be-vaccinated-against-covid-19. Last updated October 1, 2021. Accessed October 1, 2021.

- 26. Ryan KA, Filipp SL, Gurka MJ, Zirulnik A, Thompson LA. Understanding influenza vaccine perspectives and hesitancy in university students to promote increased vaccine uptake. Heliyon 2019;5(10):e02604. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jones M, Cook R. Intent to receive an HPV vaccine among university men and women and implications for vaccine administration. J Am Coll Health 2008;57(1):23–32. 10.3200/JACH.57.1.23-32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. People with certain medical conditions. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-with-medical-conditions.html. Accessed June 13, 2021.

- 29. Peterson S, Toribio N, Farber J, Hornick D. Nonresponse bias report for the 2020 Household Pulse Survey. US Census Bureau. https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/demo/technical-documentation/hhp/2020_HPS_NR_Bias_Report-final.pdf. March 24, 2021. Accessed June 22, 2021.

- 30. Bugenske E, Stokley S, Kennedy A, Dorell C. Middle school vaccination requirements and adolescent vaccination coverage. Pediatrics 2012;129(6):1056–63. 10.1542/peds.2011-2641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Calo WA, Gilkey MB, Shah PD, Moss JL, Brewer NT. Parents’ support for school-entry requirements for human papillomavirus vaccination: a national study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2016;25(9):1317–25. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-1159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Malone KM, Hinman AR. Vaccination mandates: the public health imperative and individual rights. In: Goodman RA, Hoffman RE, Lopez W, Matthews GW, Rothstein MA, Foster K, editors. Law in public health practice. Oxford University Press; 2007. p. 338–40. [Google Scholar]

- 33. El Amin AN, Parra MT, Kim-Farley R, Fielding JE. Ethical issues concerning vaccination requirements. Public Health Rev 2012;34:14. 10.1007/BF03391666 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gostin LO, Salmon DA, Larson HJ. Mandating COVID-19 vaccines. JAMA 2021;325(6):532–3. 10.1001/jama.2020.26553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]