Abstract

Objective

Given the complexities of testing the translational capability of new artificial intelligence (AI) tools, we aimed to map the pathways of training/validation/testing in development process and external validation of AI tools evaluated in dedicated randomised controlled trials (AI-RCTs).

Methods

We searched for peer-reviewed protocols and completed AI-RCTs evaluating the clinical effectiveness of AI tools and identified development and validation studies of AI tools. We collected detailed information, and evaluated patterns of development and external validation of AI tools.

Results

We found 23 AI-RCTs evaluating the clinical impact of 18 unique AI tools (2009–2021). Standard-of-care interventions were used in the control arms in all but one AI-RCT. Investigators did not provide access to the software code of the AI tool in any of the studies. Considering the primary outcome, the results were in favour of the AI intervention in 82% of the completed AI-RCTs (14 out of 17). We identified significant variation in the patterns of development, external validation and clinical evaluation approaches among different AI tools. A published development study was found only for 10 of the 18 AI tools. Median time from the publication of a development study to the respective AI-RCT was 1.4 years (IQR 0.2–2.2).

Conclusions

We found significant variation in the patterns of development and validation for AI tools before their evaluation in dedicated AI-RCTs. Published peer-reviewed protocols and completed AI-RCTs were also heterogeneous in design and reporting. Upcoming guidelines providing guidance for the development and clinical translation process aim to improve these aspects.

Keywords: artificial intelligence, decision support systems, clinical, data science, machine learning, medical informatics

Summary box.

What is already known?

Randomised controlled trials generating the highest grade of evidence are starting to emerge for AI tools in medicine (AI-RCTs).

Even though distinct steps for the development process of clinical diagnostic and prognostic tools are established, there is no specific guidance for AI-based tools and for the conduct of AI-RCTs.

What does this paper add?

A limited number of AI-RCTs have been completed and reported.

AI-RCTs are characterised by heterogenous design and reporting.

There is significant variation in the patterns of development and validation for AI tools before their evaluation in AI-RCTs.

Data that would allow independent replication and implementation of the AI tools are usually not provided in the AI-RCTs.

Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) methods are playing an increasingly important role in digital healthcare transformation and precision medicine, particularly because of breakthroughs in diagnostic and prognostic applications developed with deep learning and other complex machine learning approaches. Numerous AI tools have been developed for diverse conditions and settings, demonstrating favourable diagnostic and prognostic performance.1–3 However, similarly to any other clinical intervention,4–6 adoption of AI tools in patient care requires careful evaluation of their external validity and their impact on downstream interventions and clinical outcomes, beyond performance metrics during development and external validation. The most robust evaluation of any diagnostic or therapeutic intervention may be performed in the setting of randomised controlled trials (RCTs), which are now slowly emerging in the AI space.

Even though distinct steps of training, validation and testing for the development of AI tools have been described, there are no standardised recommendations for AI-based diagnostic and predictive modelling in biomedicine.7–10 In addition, overfitting, or the phenomenon of training an AI model that is too closely aligned with a limited training dataset such that it has no generalisation ability, is often of concern in highly parameterised AI models. External validation of AI tools aiming to verify a hyperparameterised model is therefore a critical step in the evaluation process. Furthermore, the extrapolation of model performance from one setting and patient population to others is not guaranteed.11 12 Moreover, concerns have been raised about the transparency of reporting in the AI literature to facilitate independent replication of AI tools.13

Given the complexities of testing the translational capability of new AI tools and the lack of coherent recommendations, we aimed to map the current pathways of training/validation/testing in development process of AI tools in any medical field and identify external validation patterns of AI tools considered for evaluation in dedicated RCTs (here mentioned as AI-RCTs).

Materials and methods

Data source and study selection process

We identified protocols of ongoing AI-RCTs and reports of completed AI-RCTs that evaluated AI tools compared with control strategies in a randomised fashion for any clinical purpose and medical condition. We searched PubMed for publications in peer-review journals in the last 20 years (last search on 31 December 2020) using the following search terms: “artificial intelligence”, “machine learning”, “neural network”, “deep learning”, “cognitive computing”, “computer vision” and “natural language processing”. We did not search for protocols of AI-RCTs published only in protocol registries since the compliance with reporting and the provided information has been shown to be poor compared with peer-reviewed protocols or published reports of clinical trials.14–18 We considered only peer-reviewed reports of protocols of AI-RCTs which provided detailed information on the trial design of our interest. We considered clinical trials in which the AI tool (algorithm) was either previously developed or was planned to be developed (trained) as part of the trial before being evaluated in the RCT. Clinical trial protocols were included irrespectively of their status (ongoing or completed). The listed references of eligible studies were also searched for additional potentially eligible studies. The detailed search algorithm is provided in online supplemental box.

bmjhci-2021-100466supp001.pdf (557.3KB, pdf)

Mapping of AI tool development: citation content analysis

For each eligible protocol and report of AI-RCT, we scrutinised the cited articles to identify any previous published study reporting on AI tool development (including training, validation or testing) or claiming external validation in an independent population than the one where the AI tool was initial developed. Each potentially eligible study identified above, was subsequently evaluated in full-text to determine whether it describes the development and/or independent evaluation (external validation) of the AI tool of interest. Finally, we searched Google Scholar for articles citing the index development study of the AI tool or its external validation (if any) in order to trace other studies of external validation (onnline supplemental box).

Data collection

A detailed list of information was gathered from each eligible protocol and report of completed AI-RCT using a standardised form which was built and modified, as required, in an iterative process. We extracted relevant information from the main manuscript and any online supplemental material. From each report, we extracted trial and population characteristics which include: single versus multicentre trial, geographical location of the contributing centres, number of arms of randomisation, level of randomisation (patient or clinicians), total sample size, power calculation approach, type of control intervention, underlying medical condition, period of recruitment, funding source (industry related, non-industry related, both, none, none reported), follow-up duration or duration of the intervention, patient-level data collection through dedicated study personnel or from electronic health records, strategies for dealing with missing data; details on the primary outcome(s) of interest which include: single or composite, continuous or binary, outcome adjudication method(s); considering the primary outcome. Among the unique AI tools, we classified the primary outcomes as therapeutic, diagnostic or feasibility outcomes. We documented whether the results of the completed AI-RCT are in favour to intervention based on the AI tool. We extracted information on whether researchers provide access to the code based on which the AI tool was built. We finally assessed the risk of bias (RoB) in the results of completed AI-RCTs that compared the effect of the AI tool compared with other intervention(s) by using the revised Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomised trials RoB 2.19

For each study describing the development or external validation of an index AI tool, we extracted the following information: year of publication, recruitment period, geographic area of study population, sample size, clinical field, and whether the authors provided any information that would allow the replication of applied coding. We considered as external validation studies those which fulfilled at least one the following conditions compared with the corresponding development study: different study population, different geographic area, different recruitment period or different group of investigators validating the AI tool.

Statistical analysis

We descriptively analysed the protocols and reports of completed AI-RCTs as a whole and separately. We considered the protocols of already published AI-RCTs as a single report with the index trial. The extracted data were summarised into narrative synthesis and presented in summary tables in the level of AI tools and in the level of AI-RCTs. For illustration purposes, we graphically summarised interconnections of the available development (training/validation/testing) studies, external validation studies and the respective AI-RCTs (either protocols of reports) for each AI tool of interest. We visually evaluated the diversity of the distributions of peer-reviewed development, external validation studies and the ongoing/published reports of AI-RCTs among the unique AI tools. We also illustrated the time lags and differences in sample sizes between different steps of development (whenever applicable) of an AI tool to subsequent evaluation in dedicated AI-RCTs. Illustrations were conducted in R (V.3.4.1; R-Project for Statistical Computing).

Results

Protocols and completed AI-RCTs

The selection process of eligible protocols and reports of AI-RCTs is summarised in online supplemental figure 1. Overall, we identified 23 unique AI-RCTs20–45 (6 protocols and 17 reports of completed AI-RCTs) evaluating the clinical effectiveness of 18 unique AI tools for a variety of conditions (tables 1 and 2, online supplemental file 1). Three of the completed AI-RCTs36 39 45 had previously published protocols.35 38 44 The identified reports were published over a 10-year period (2009–2020). Half of the AI-RCTs were multicentre (52%) and the majority compared the AI-based intervention to a single control intervention (87%). The median target sample size reported in the protocols of AI-RCTs was 298 (IQR 219–850), whereas for the published AI-RCTs was 214 (IQR 100–437) (table 2, online supplemental table 1). Power calculations were available in 18 out of 23 AI-RCTs. The control arms consisted of standard-of-care interventions in all but one study in which a sham intervention was used as control. In one trial, the investigators also considered a historical control group in addition to the two randomised groups in the trial.37 Ten AI-RCTs were funded by non-industry sponsors and seven trials did not specify the financial source. The investigators did not specify any strategies for handling missing data in most AI-RCTs (19 out of 23, 83%). Outcome ascertainment was based on electronic health records in the minority of the AI-RCTs (4 out of 23, 17%), while in the remaining studies either was unclear or conventional adjudication methods were applied. A binary or continuous primary outcome was considered in 7 (30%) and 14 (61%) of the trials. Among the 18 unique AI tools (table 1), 10 tools were examined for therapeutic outcomes, 6 for diagnostic and 2 for feasibility. The results according to the primary outcome favoured the AI intervention in 82% of the completed AI-RCTs (14 out of 17), with 1 trial claiming lower in-hospital mortality rates with the AI intervention25 (table 2, online supplemental table 2). None of the AI-RCTs reported their intention to provide access to the coding of the AI tool. Online supplemental table 3 summarises the detailed risk-of-bias judgement for each domain and the overall judgement for each AI-RCT. Three trials were at low RoB, five trials were judged to raise ‘some concerns’ and nine to be at ‘high RoB’, mainly due to the lack of appropriate/complete reporting related to adherence of intended interventions and in measurement of the outcome of interest.

Table 1.

Descriptive summary of 18 artificial intelligence tools evaluated in AI-RCTs

| AI-RCT/AI tool | Medical field | Aim | Description | Softwares/packages used | Primary outcome | Outcome classification | Main finding |

| El-Soll et al20/na | Pulmonary diseases | Prediction of optimal CPAP titration | A general regression neural network with tree-layer structure (input layer, hidden layer and output layer) was trained to predict optimal CPAP pressure based on five input variables. | Neuroshell 2, Ward Systems, Frederick, MD | Time of achieving optimal continuous positive airway pressure titration | Therapeutic | AI guided CPAP titration resulted in lower time to optimal CPAP and lower titration failure rate. |

| Martin et al21/Patient Journey Record system (PaJR) | Chronic diseases | Early detection of adverse trajectories and reduction of readmissions | Summaries of semistructured phone calls about well-being and health-concerns analysed by machine learning-based and rule-based algorithms. By detection of signs of health deterioration, an alarm was triggered. Alarms were reviewed by a clinical case manager who decided subsequent interventions. | Not specified | Unplanned emergency ambulatory care sensitive admissions | Therapeutic | AI tool allowed early identification of health concerns and resulted in reduction of emergency ambulatory care sensitive admissions. |

| Zeevi et al22; Popp et al27/na | Nutrition/endocrinology | Prediction of postprandial glycaemic response | A machine learning algorithm employing stochastic gradient boosting regression was developed to predict personalised postprandial glycaemic responses to real-life meals. Inputs included blood parameters, dietary habits, anthropometrics, physical activity and gut microbiota. | Code adapted from the sklearn 0.15.2 Gradient Boosting Regressor class | Postprandial glycaemic responses | Therapeutic | AI tool accurately predicted postprandial glycaemic responses. Individualised dietary interventions resulted in lower postprandial glycaemic responses and alterations to gut microbiota. |

| Piette et al23/na | Behavioural | Improvement of chronic low back pain by personalised cognitive behavioural therapy | A reinforcement learning algorithm is employed to customise cognitive behavioural therapy in patients with chronic low back pain. The algorithm learns from patient feedback and pedometer step counts to provide personalised therapy recommendations. | Not specified | 24-item Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire | Therapeutic | Not applicable (protocol of AI-RCT) |

| Sadasivam et al24/PERSPeCT | Behavioural | Smoking cessation | A hybrid recommender system employing content-based and collaborative filtering methods was developed to provide personalised messages supporting smoking cessation. Data sources included message-metadata together with implicit (ie, website view patterns) and explicit (item ratings) user feedbacks. Each participant received AI-selected messages from a message database that matched their readiness to quit status. | Not specified | Smoking cessation | Therapeutic | After 30 days, there was no difference in smoking cessation rates, although those receiving AI-tailored computer messages rated them as being more influential. |

| Shimabukuro et al25/InSight | Infectious diseases | Sepsis prediction | A machine learning based classifier with gradient tree boosting was developed to generate risk scores predictive of sepsis, severe sepsis or septic shock based on electronic health record data. Depending on the predicted risk, an alarm was triggered. Further evaluation and treatment was according to standard guidelines. | Matlab | Average hospital length of stay | Therapeutic | AI-guided monitoring decreased length of hospital stay and in-hospital mortality. |

| Fulmeret al26/Tess | Behavioural | Reduction of depression and anxiety | An AI-based chatbot was designed to deliver personalised conversations in the form of integrative mental health support, psychoeducation and reminders. Users could enter both free-text and/or select predefined responses. | Not specified | Self-report tools (PHQ-9, GAD-7, PANAS) for symptoms of depression and anxiety | Therapeutic | AI-based intervention resulted in reduction of symptoms of depression and anxiety. |

| Wang et al28 32/EndoScreener | Gastroenterology | Automatic polyp and adenom detection | A deep CNN based on the SegNet architecture was trained to automatically identify polyps in real time during colonoscopy. | Not specified | Adenoma detection rate | Diagnostic | Automatic polyp detection system resulted in a significant increased detection rate of adenomas and polyps. |

| Wu et al29; Chen et al33/Wisense/ Endoangel |

Gastroenterology | Quality improvement of endoscopy by automatic identification of blind spots | A deep CNN combined with deep reinforcement learning was designed to automatically detect blind spots during EGD. | TensorFlow | Blind spot rate | Feasibility | AI reduced blind spot rate during esophagogastroduodenoscopy |

| Gong et al34/Wisense/ Endoangel |

Gastroenterology | Quality improvement of endoscopy by automatic identification of adenomas | A deep CNN combined with deep reinforcement learning was designed to automatically detect adenomas during colonoscopy. | TensorFlow | Adenoma detection rate | Diagnostic | AI increased adenoma detection rate during colonoscopy |

| Oka et al30/Asken | Nutrition/endocrinology | Automated nutritional intervention to improve glycaemic control in patients with diabetes mellitus | Participants use a mobile app to select foods from a large database (>100 000) of menus, which are analysed with regards to their energy and nutrition content by an AI-powered photo analysis system. The trial will compare dietary interventions based on AI-supported vs standard nutritional therapy. | Not specified | Change in glycated haemoglobin levels | Therapeutic | Not applicable (protocol of AI-RCT) |

| Lin et al31/CC-Cruiser | Ophtalmology | Diagnosis and risk stratification of childhood cataracts | A collaborative cloud platform encompassing automatic analysis of uploaded split-lamp photographs of the ocular anterior segment by an AI engine was established. Output includes diagnosis, risk stratification and treatment recommendations. | Not specified | Diagnostic performance for childhood cataract | Diagnostic | AI tool was less accurate than senior consultants in diagnosing childhood cataracts, but was less time-consuming. |

| Wijnberge et al35 36; Schneck et al37; Maheshwari et al38 39/EV1000 HPI monitoring device | Surgery/anaesthesia | Prediction of intraoperative hypotension | A machine learning algorithm to predict hypotensive episodes from arterial pressure waveforms was designed. The model output was implemented as an early warning system based on the estimated ‘hypotension prediction index’(0–100, with higher numbers reflecting higher likelihood of incipient hypotension) and included information about the underlying cause for the predicted hypotension (vasoplegia, hypovolaemia, low contractility). | Matlab | Time-weighted average of hypotension during surgery/frequency and absolute and relative duration of intraoperative hypotension | Therapeutic | The AI-based early warning system performed different under different clinical settings (ie, elective non-cardiac surgery, primary total hip arthroplasty, moderate to high risk non-cardiac surgery patients). |

| Auloge et al40/na | Orthopaedics | Facilitation of percutaneous vertebroplasty by augmented reality/ artificial intelligence-based navigation | A navigation system integrating four video cameras within the flat-panel detector of a standard C-arm fluoroscopy machine was developed, including an AI software that automatically recognised osseous landmarks, identified each vertebral level and displayed 2D/3D planning images on the user interface. After manual selection of the target vertebra, the software suggests an optimal trans-pedicular approach. Once trajectory is validated, the C-arm automatically rotates and the virtual trajectory is superimposed over the real-world camera input with overlaid, motion-compensated needle trajectories. | Not specified | Technical feasibility of trocar placement using augmented reality/artificial intelligence guidance | Feasibility | AI-guided percutaneous vertebroplasty was feasible and resulted in lower radiation exposure compared with standard fluoroscopic guidance. |

| Wong et al41/Everion/ Biovitals |

Infectious diseases | Early detection of COVID-19 in quarantine subjects | Data from a wearable biosensor worn on the upper arm are automatically transferred in real time through a smartphone app to a cloud storage platform and subsequently analysed by the AI software. The results (including risk prediction of critical events) are displayed on a web-based dashboard for clinical review. | Not specified | Time to diagnosis of coronavirus disease 19 | Diagnostic | Not applicable (protocol of AI-RCT) |

| Aguilera et al42/na | Behavioural | Increase physical activity in patients with diabetes and depression by tailored messages via AI mobile health application | Participants receive daily messages from a messaging bank, with message category, timing and frequency being selected by a reinforcement learning algorithm. The algorithm employs Thompson Sampling to continuously learn from contextual features like previous physical activity, demographic and clinical characteristics. | Not specified | Improvement in physical activity defined by daily step counts | Therapeutic | Not applicable (protocol of AI-RCT) |

| Hill et al43/na | Cardiology | Atrial fibrillation detection | An atrial fibrillation risk prediction algorithm was developed using machine learning techniques on retrospective data from nearly 3 000 000 adult patients without history of atrial fibrillation. The output is provided as a risk score for the likelihood of atrial fibrillation. | R | Prevalence of diagnosed atrial fibrillation | Diagnostic | Not applicable (protocol of AI-RCT) |

| Yao et al44 45/na | Cardiology | ECG AI-guided screening for low left ventricular ejection fraction | A CNN model has been trained to predict low LVEF from 10 s 12-lead ECGs strips from nearly 98’000 patients with paired ECG-TTE data. The final model consisted of 6 convolutional layers, each followed by a nonlinear ‘Relu’ activation function, a batch-normalisation layer and a max-pooling layer. The binary output will be incorporated into the electronic health record and triggered a recommendation for TTE in case of a positive screening result (predicted LVEF ≤35%). | Keras, TensorFlow, Python | Newly discovered left ventricular ejection fraction <50% | Diagnostic | An AI algorithm applied on existing ECGs enabled the early diagnosis of low left ventricular ejection fraction in patients managed in primary care practices. |

AI-RCT, artificial intelligence randomised controlled trial; CNN, convolutional neural network; CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; GAD-7, General Anxiety Disorder-7; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; na, not available; PANAS, Positive and Negative Affect Schedule; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9; TTE, transthoracic echocardiography.

Table 2.

Characteristics of peer-reviewed protocols and completed RCTs evaluating artificial intelligence tools

| Characteristics | AI-RCTs (n=23) |

Protocols of AI-RCTs (n=6) |

Completed AI-RCTs (n=17) |

| No of centres, n (%) | |||

| Single | 11 (48) | 1 (17) | 10 (59) |

| Multicentre | 12 (52) | 5 (83) | 7 (41) |

| Geographic area, n (%) | |||

| Asia | 8 (35) | 2 (33) | 6 (35) |

| Europe | 5 (22) | 1 (17) | 4 (24) |

| North America | 9 (39) | 3 (50) | 6 (35) |

| Other | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) |

| Arms of randomisation, n (%) | |||

| Two | 20 (87) | 5 (83) | 15 (88) |

| Three | 3 (13) | 1 (17) | 2 (12) |

| Level of randomisation, n (%) | |||

| Patients | 22 (96) | 6 (100) | 16 (94) |

| Clinicians | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) |

| Sample size | |||

| Median (IQR) | 214 (108–571) | 298 (219–830) | 214 (100–437) |

| Min | 20 | 100 | 20 |

| Max | 22 641 | 18 000 | 22 641 |

| Power calculations, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 18 (78) | 6 (100) | 12 (71) |

| No | 5 (22) | 0 (0) | 5 (29) |

| Type of control intervention, n (%) | |||

| Standard of care | 22 (96) | 6 (100) | 16 (94) |

| Sham procedure | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) |

| Funding source, n (%) | |||

| Industry related | 4 (17) | 1 (17) | 3 (18) |

| Non-industry related | 10 (43) | 4 (66) | 6 (35) |

| None reported | 7 (30) | 1 (17) | 6 (35) |

| None | 2 (9) | 0 (0) | 2 (12) |

| Data sources, n (%) | |||

| Dedicated personnel | 5 (22) | 2 (33) | 3 (18) |

| Dedicated personnel and EHR | 4 (17) | 2 (33) | 2 (12) |

| EHR | 4 (17) | 2 (33) | 2 (12) |

| Not applicable | 4 (17) | 0 (0) | 4 (23) |

| Not specified | 6 (27) | 0 (0) | 6 (35) |

| Strategies for missing data, n (%) | |||

| Specified | 4 (17) | 4 (67) | 0 (0) |

| Not specified | 19 (83) | 2 (33) | 17 (100) |

| Primary outcome(s), n (%) | |||

| Binary | 7 (30) | 0 (0) | 7 (41) |

| Binary and continuous | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) |

| Categorical | 1 (4) | 1 (17) | 0 (0) |

| Continuous | 14 (61) | 5 (83) | 9 (53) |

| Primary outcome favours AI tool, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 13 (57) | 0 (0) | 13 (76) |

| No | 2 (9) | 0 (0) | 2 (12) |

| Not applicable | 8 (34) | 6 (100) | 2 (12) |

| Different geographic area of study population in development study and AI-RCT, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 3 (14) | 1 (17) | 2 (12) |

| No | 12 (52) | 1 (17) | 11 (65) |

| Not applicable* | 8 (34) | 4 (66) | 4 (23) |

| External validation of AI tool, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 11 (48) | 2 (33) | 9 (53) |

| No | 12 (52) | 4 (67) | 8 (47) |

| Different geographic area† | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Different time period† | 11 (48) | 2 (33) | 9 (53) |

*The respective development study was not identified.

†Compared with the development study.

AI-RCTs, artificial intelligence randomised controlled trials; EHR, electronic health records.

Development, external validation and clinical evaluation pathways of AI tools

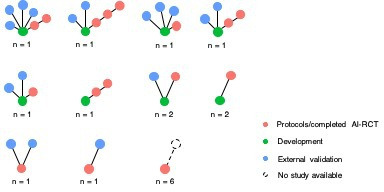

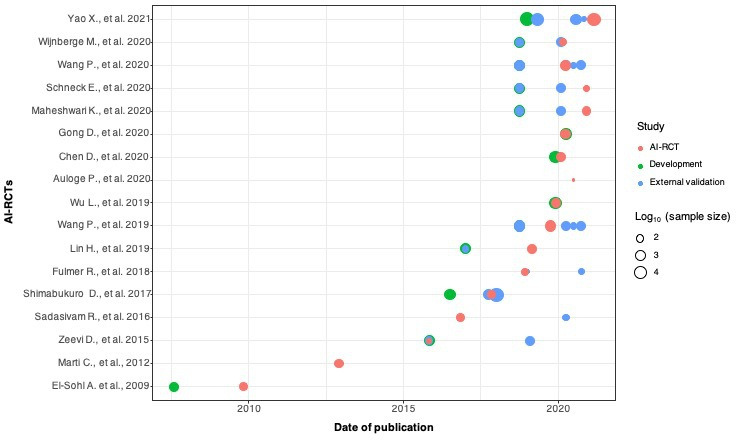

We identified considerable dissimilarities in the patterns of development, external validation and clinical evaluation steps among AI tools (figures 1 and 2, online supplemental table 4). A peer-reviewed publication describing the development process was not found for 8 out of the 18 unique AI tools. In 12 AI-RCTs, the study population originated from the same geographic area and population as the one where the AI tool was developed in. We were able to identify at least one external validation study linked to a trial only in 11 out of the 23 ongoing/completed AI-RCTs. All of the external validation studies considered a different recruitment period compared with that in the development study, but from the same geographical area in all 11 cases. The number of external validation studies ranged from 1 to 4 per AI tool (figure 1). Three AI tools were evaluated in two different AI-RCTs, and one AI tool was evaluated in three different AI-RCTs with differences in patient populations and examined outcomes (table 1 and figure 1). Among the AI tools with external validation studies, in 6 cases the external validation studies were published at the same time or clearly after the corresponding AI-RCT (figure 2). In those six cases, the external validation studies applied the AI tool in different populations and/or clinical settings, compared with those where it was developed and those studied in the AI-RCT.

Figure 1.

Patterns of pathways of development (training, validation and/or testing), external validation and clinical evaluation of artificial intelligence tools in ongoing and completed clinical trials (n=23). In network level, each circle corresponds to an individual study (green, blue, and red for development, external validation and AI-RCTs, respectively). The number below each network represents the number of unique AI tools having identified with the respective pattern (network) of studies. For example, the first network of the top row corresponds to a unique AI tool for which a development study (green circle), four external validation studies (blue circles), and two AI-RCTs (red circles) were found. AI-RCTs, artificial intelligence randomised controlled trials.

Figure 2.

Timelines of publications and sample sizes of development (training, validation and/or testing), external validation studies and completed AI-RCTs (n=17). Each circle corresponds to a unique study (development (training, validation, testing) studies in green, external validation studies in blue, and AI-RCTs in red). Due to the wide range of studies’ sample sizes, the values are displaying in logarithmic (log10) scale. AI-RCTs, artificial intelligence randomised controlled trials.

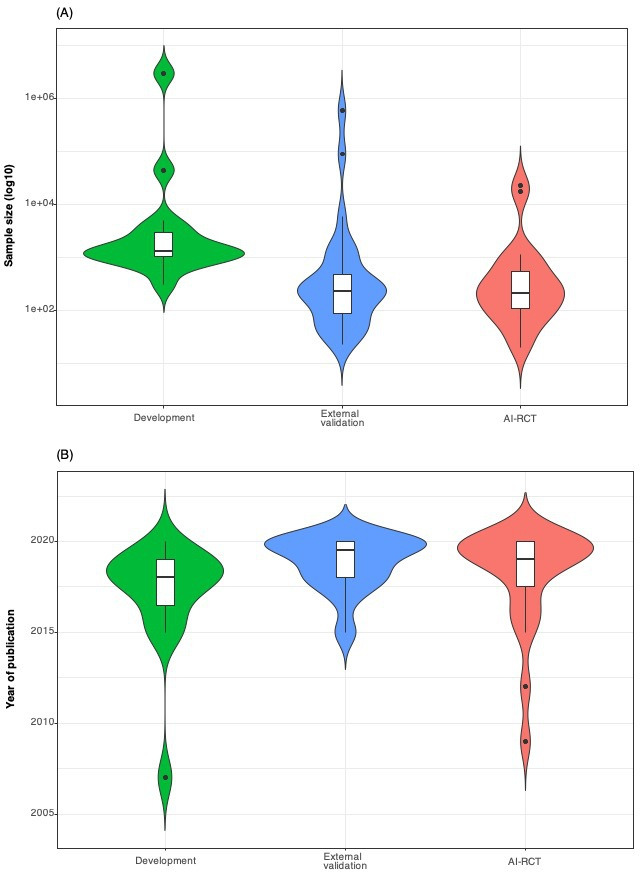

Among the 17 completed AI-RCTs, the distribution of the sample sizes and timelines of publications for development, external validation and AI-RCT reports is shown in figures 2 and 3. The sample sizes of the development studies were larger than the respective external validation studies and AI-RCTs, whereas external validation studies and AI-RCTs did not differ in sample sizes. Median time from publication of a development study to publication of the respective AI-RCT was 1.4 years (IQR 0.2–2.2). The time lag between publication of the development studies to the publication of AI-RCTs varied for different AI tools, but there was considerable overlap of the timelines of external validation and AI-RCT publications (table 1, figure 2, online supplemental tables 1 and 4).

Figure 3.

Violin plots showing in comparison the distributions of sample sizes (A) and years of publication (B) of development (training, validation and/or testing), external validation studies and completed AI-RCTs (n=17). AI-RCT, artificial intelligence randomised controlled trials.

Discussion

Large scale real-world data collected from electronic-health records have allowed the development of diagnostic and prognostic tools based on machine learning approaches.46–52 Evaluations of the clinical impact of such tools in dedicated RCTs are now starting to emerge in the literature. Our empirical assessment of the literature identified significant variation in the patterns of AI tool development (training, validation, testing) and external (independent) validation leading up to their evaluation in dedicated AI-RCTs. In this early phase of novel AI-RCTs, trials are characterised by heterogeneous design and reporting. Data that would allow independent replication and implementation of AI tools were not available in any of the AI-RCTs.

There is growing recognition that AI tools need to be held to the same rigorous standard of evidence as other diagnostic and therapeutic tools in medicine with standardised reporting.53–55 The recently published extensions of the COSNORT and Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT) statements for RCTs of AI-based interventions (namely Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT)-AI56 and SPIRIT-AI)57 are beginning to provide such a framework. Among the items mandated by these documents, investigators in AI-RCT have to provide better clarity around the intended use of the AI intervention, descriptions how the AI intervention can be integrated into the trial setting, and the setting expectations that investigators make the AI intervention and/or its code assessable. Although most of the studies included in the current review were published before these guidelines, the marked heterogeneity in current reporting underscore the urgency of this call and provide a standard for the ongoing evaluation of these kinds of studies.

RCTs remain the cornerstone of evaluation of diagnostic or therapeutic interventions proposed for clinical use, and this should be no less true for AI interventions. While the experience with the clinical application of AI tools is still early, the evaluation standards of these tools should follow well established norms. AI has demonstrated great promise in transforming many aspects of patient care and healthcare delivery, but the rigorous evaluation standards has lagged for AI tools. Despite numerous published AI applications in medicine,1–3 in this empirical assessment we have found that a very small fraction has so far undergone evaluation in dedicated clinical trials. We identified significant variation of model development processes leading up to the AI-RCTs. After initial development of an AI tool, at least one external validation study for that particular tool was found for only 11 out of the 23 AI-RCTs. Furthermore, the AI-RCTs were almost always conducted in the same geographic areas as their respective development studies. Thus, the AI-RCTs in this empirical assessment often failed to provide sufficient information regarding the generalisability and external validity of the AI tools. When considering the application of AI tools in the real world, a ‘table of ingredients’ accompanying the AI tool could be of value. Such a label would include information on how the tool was developed and whether it has been externally validated, including the specific populations, demographic profiles, racial mix, inpatient versus outpatient settings, and other key details. This would allow a potential user to determine whether the AI tool is applicable to their patient or population of interest and whether any deviations in diagnostic or prognostic performance are to be expected.

Along these lines, as with any type of RCT, the choice of primary outcomes in AI-RCTs is also important to consider. Improvement in therapeutic efficacy outcomes with direct patient relevance may be the ultimate criterion of value of an AI tool, but these may also be the most difficult to demonstrate improvements for. The number of studies in each of the three outcome classes in our study (therapeutic, diagnostic, feasibility) was too small to reach conclusions about differences in the probability of statistically significant results between classes. It should also be noted that for diagnostic AI tools, diagnostic performance outcomes that align with the scope of the intervention would be appropriate. However, interpretation of such findings should account for likely dilution of any effect when translating differences in diagnostic outcomes to downstream clinical outcomes.58 Ultimately, investigation of patient-centric outcomes, should remain a priority whenever possible.

The optimal process for the clinical evaluation of AI tools, ranging from model development to AI-RCTs to real-world implementation, is not yet well defined. Dedicated guidelines on the development, reporting and bridging the development-to-implementation gap of AI tools for prognosis or diagnosis, namely Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis-AI (TRIPOD-AI),59 Prediction model Risk Of Bias ASsessment Tool-AI (PROBAST-AI),59 Developmental and Exploratory Clinical Investigation of Decision-AI (DECIDE-AI),60 Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies-AI (STARD-AI),61 Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies-AI (QUADAS-AI),62 will be available soon. The heterogeneity in development, validation and reporting in the existing AI literature that we found in this study might be largely attributable to the lack of consensus on research practices and reporting standards in this space. The translational process from development to clinical evaluation of AI tools is in the early phase of a broader scrutiny of AI in various medical disciplines. The upcoming guideline documents are likely to enhance the reliability, replicability, validity and generalisability of this literature.

Furthermore, it is unknown whether all AI tools necessitate testing in traditional, large-scale AI-RCTs.63 Well-powered, large RCTs that are likely to provide conclusive results are costly, resource intensive and take a long time to complete. Therefore, a clinical evaluation model that routinely requires RCTs may not represent a realistic expectation for the majority of AI tools. However, the ongoing digital transformation in healthcare allows researchers to simplify time-consuming and costly steps of traditional RCTs and to improve efficiency. For example, patient recruitment, follow-up and outcome ascertainment may be performed via nationwide linkage to centralised electronic health records. Natural language processing tools may allow automated screening for patient eligibility and collection of information of patient characteristics and outcomes. Existing web-based, patient-facing portals that are the norm for most healthcare institutions may allow a fully virtual consent process for recruitment. for outcomes’ ascertainment. The extensions of the COSNORT and SPIRIT statements for RCTs of AI-based interventions (namely CONSORT-AI56 and SPIRIT-AI)57 underscore these concepts for facilitating a novel model of AI-RCT.

Limitations

Our empirical evaluation has limitations. First, a number of potentially eligible ongoing trials have not been included, since we summarised peer-reviewed protocols and final reports of AI-RCTs published in PubMed, whereas trials registered in online registries were not considered. However, as has been previously shown,14–18 64 registered protocols often suffer from incomplete reporting, lack of compliance with the conditions for registration and out-of-date information, which would not have allowed us to appropriately characterise the AI tools and their respective development pathways. Second, as part of this evaluation we did not consider a control group of trials (ie, trials evaluating the clinical impact of traditional diagnostic or prognostic tools). However, such trials could not be directly comparable to the AI-RCTs due to fundamental differences in studied interventions and populations. Third, we were not able to comparatively assess the discriminatory performance of the AI tools across the distinct steps of training/validation/testing and external validation, since such performance metrics were neither systematically nor uniformly reported.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have found that evaluation of AI tools in dedicated RCTs is still infrequent. There is significant variation in patterns of development and validation for AI tools before their evaluation in RCTs. Published peer-reviewed protocols and completed AI-RCTs also varied in design and reporting. Most AI-RCTs do not test the AI tools in geographical areas outside of those where the tools were developed, therefore generalisability remains largely unaddressed. As AI applications are increasingly reported throughout medicine, there is a clear need for structured evaluation of their impact on patients with a focus on effectiveness and safety outcomes, but also costs and patient-centred care, before their large-scale deployment.65 The upcoming guidelines for AI tools aim to guide researchers and fill the translational gaps in the conduct and reporting of development and translation steps. All steps in the translation pathway of these tools should serve the development of meaningful and impactful AI tools without compromise under the pressure of innovation.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors reviewed the final manuscript for submission and contributed to the study as follows: GCMS contributed to the study design, data extraction and management, interpretation and writing of manuscript. GCMS is the guarantor and responsible for the overall content. GCMS accepts full responsibility for the work and the conduct of the study, had access to the data, and controlled the decision to publish. RS contributed to data extraction and management. PAN contributed to interpretation and writing of manuscript. PAF contributed to interpretation and writing of manuscript. KCS contributed to study design, interpretation and writing of manuscript. CJP contributed to interpretation and writing of manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement statement: Not applicable.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information. Not applicable.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Not required.

References

- 1.Gulshan V, Peng L, Coram M, et al. Development and validation of a deep learning algorithm for detection of diabetic retinopathy in retinal fundus Photographs. JAMA 2016;316:2402–10. 10.1001/jama.2016.17216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Esteva A, Kuprel B, Novoa RA, et al. Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks. Nature 2017;542:115–8. 10.1038/nature21056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ehteshami Bejnordi B, Veta M, Johannes van Diest P, et al. Diagnostic assessment of deep learning algorithms for detection of lymph node metastases in women with breast cancer. JAMA 2017;318:2199–210. 10.1001/jama.2017.14585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Royston P, Moons KGM, Altman DG, et al. Prognosis and prognostic research: developing a prognostic model. BMJ 2009;338:b604–7. 10.1136/bmj.b604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siontis GCM, Tzoulaki I, Castaldi PJ, et al. External validation of new risk prediction models is infrequent and reveals worse prognostic discrimination. J Clin Epidemiol 2015;68:25–34. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moons KGM, Altman DG, Vergouwe Y, et al. Prognosis and prognostic research: application and impact of prognostic models in clinical practice. BMJ 2009;338:b606–90. 10.1136/bmj.b606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collins GS, Reitsma JB, Altman DG, et al. Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD): the TRIPOD statement. BMJ 2015;350:g7594. 10.1136/bmj.g7594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collins GS, Moons KGM. Reporting of artificial intelligence prediction models. Lancet 2019;393:1577–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30037-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu X, Faes L, Calvert MJ, et al. Extension of the CONSORT and spirit statements. Lancet 2019;394:1225. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31819-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park SH, Han K. Methodologic guide for evaluating clinical performance and effect of artificial intelligence technology for medical diagnosis and prediction. Radiology 2018;286:800–9. 10.1148/radiol.2017171920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kohli M, Prevedello LM, Filice RW, et al. Implementing machine learning in radiology practice and research. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2017;208:754–60. 10.2214/AJR.16.17224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aerts HJWL,. The potential of Radiomic-Based phenotyping in precision medicine: a review. JAMA Oncol 2016;2:1636–42. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.2631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vollmer S, Mateen BA, Bohner G, et al. Machine learning and artificial intelligence research for patient benefit: 20 critical questions on transparency, replicability, ethics, and effectiveness. BMJ 2020;368:l6927. 10.1136/bmj.l6927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeVito NJ, Bacon S, Goldacre B. Compliance with legal requirement to report clinical trial results on ClinicalTrials.gov: a cohort study. Lancet 2020;395:361–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)33220-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zarin DA, Tse T, Williams RJ, et al. Update on trial registration 11 years after the ICMJE policy was established. N Engl J Med 2017;376:383–91. 10.1056/NEJMsr1601330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anderson ML, Chiswell K, Peterson ED, et al. Compliance with results reporting at ClinicalTrials.gov. N Engl J Med 2015;372:1031–9. 10.1056/NEJMsa1409364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adam GP, Springs S, Trikalinos T, et al. Does information from ClinicalTrials.gov increase transparency and reduce bias? results from a five-report case series. Syst Rev 2018;7:59. 10.1186/s13643-018-0726-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zarin DA, Tse T, Williams RJ, et al. The ClinicalTrials.gov results database--update and key issues. N Engl J Med 2011;364:852–60. 10.1056/NEJMsa1012065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, et al. Rob 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019;366:l4898. 10.1136/bmj.l4898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.El Solh A, Akinnusi M, Patel A, et al. Predicting optimal CPAP by neural network reduces titration failure: a randomized study. Sleep Breath 2009;13:325–30. 10.1007/s11325-009-0247-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin CM, Vogel C, Grady D, et al. Implementation of complex adaptive chronic care: the patient journey record system (PaJR). J Eval Clin Pract 2012;18:1226–34. 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2012.01880.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zeevi D, Korem T, Zmora N, et al. Personalized nutrition by prediction of glycemic responses. Cell 2015;163:1079–94. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Piette JD, Krein SL, Striplin D, et al. Patient-Centered pain care using artificial intelligence and mobile health tools: protocol for a randomized study funded by the US department of Veterans Affairs health services research and development program. JMIR Res Protoc 2016;5:e53. 10.2196/resprot.4995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sadasivam RS, Borglund EM, Adams R, et al. Impact of a collective intelligence tailored messaging system on smoking cessation: the perspect randomized experiment. J Med Internet Res 2016;18:e285. 10.2196/jmir.6465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shimabukuro DW, Barton CW, Feldman MD, et al. Effect of a machine learning-based severe sepsis prediction algorithm on patient survival and hospital length of stay: a randomised clinical trial. BMJ Open Respir Res 2017;4:e000234. 10.1136/bmjresp-2017-000234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fulmer R, Joerin A, Gentile B, et al. Using psychological artificial intelligence (Tess) to relieve symptoms of depression and anxiety: randomized controlled trial. JMIR Ment Health 2018;5:e64. 10.2196/mental.9782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Popp CJ, St-Jules DE, Hu L, et al. The rationale and design of the personal diet study, a randomized clinical trial evaluating a personalized approach to weight loss in individuals with pre-diabetes and early-stage type 2 diabetes. Contemp Clin Trials 2019;79:80–8. 10.1016/j.cct.2019.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang P, Berzin TM, Glissen Brown JR, et al. Real-Time automatic detection system increases colonoscopic polyp and adenoma detection rates: a prospective randomised controlled study. Gut 2019;68:1813–9. 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-317500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu L, Zhang J, Zhou W, et al. Randomised controlled trial of WISENSE, a real-time quality improving system for monitoring blind spots during esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Gut 2019;68:2161–9. 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-317366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oka R, Nomura A, Yasugi A, et al. Study Protocol for the Effects of Artificial Intelligence (AI)-Supported Automated Nutritional Intervention on Glycemic Control in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Ther 2019;10:1151–61. 10.1007/s13300-019-0595-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin H, Li R, Liu Z, et al. Diagnostic efficacy and therapeutic decision-making capacity of an artificial intelligence platform for childhood cataracts in eye clinics: a multicentre randomized controlled trial. EClinicalMedicine 2019;9:52–9. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2019.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang P, Liu X, Berzin TM, et al. Effect of a deep-learning computer-aided detection system on adenoma detection during colonoscopy (CADe-DB trial): a double-blind randomised study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020;5:343–51. 10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30411-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen D, Wu L, Li Y, et al. Comparing blind spots of unsedated ultrafine, sedated, and unsedated conventional gastroscopy with and without artificial intelligence: a prospective, single-blind, 3-parallel-group, randomized, single-center trial. Gastrointest Endosc 2020;91:332–9. 10.1016/j.gie.2019.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gong D, Wu L, Zhang J, et al. Detection of colorectal adenomas with a real-time computer-aided system (ENDOANGEL): a randomised controlled study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020;5:352–61. 10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30413-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wijnberge M, Schenk J, Terwindt LE, et al. The use of a machine-learning algorithm that predicts hypotension during surgery in combination with personalized treatment guidance: study protocol for a randomized clinical trial. Trials 2019;20:582. 10.1186/s13063-019-3637-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wijnberge M, Geerts BF, Hol L, et al. Effect of a machine Learning-Derived early warning system for intraoperative hypotension vs standard care on depth and duration of intraoperative hypotension during elective noncardiac surgery: the hype randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2020;323:1052–60. 10.1001/jama.2020.0592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schneck E, Schulte D, Habig L, et al. Hypotension prediction index based protocolized haemodynamic management reduces the incidence and duration of intraoperative hypotension in primary total hip arthroplasty: a single centre feasibility randomised blinded prospective interventional trial. J Clin Monit Comput 2020;34:1149–58. 10.1007/s10877-019-00433-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maheshwari K, Shimada T, Fang J, et al. Hypotension prediction index software for management of hypotension during moderate- to high-risk noncardiac surgery: protocol for a randomized trial. Trials 2019;20:255. 10.1186/s13063-019-3329-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maheshwari K, Shimada T, Yang D, et al. Hypotension prediction index for prevention of hypotension during moderate- to high-risk noncardiac surgery. Anesthesiology 2020;133:1214–22. 10.1097/ALN.0000000000003557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Auloge P, Cazzato RL, Ramamurthy N, et al. Augmented reality and artificial intelligence-based navigation during percutaneous vertebroplasty: a pilot randomised clinical trial. Eur Spine J 2020;29:1580–9. 10.1007/s00586-019-06054-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wong CK, Ho DTY, Tam AR, et al. Artificial intelligence mobile health platform for early detection of COVID-19 in quarantine subjects using a wearable biosensor: protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2020;10:e038555. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-038555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aguilera A, Figueroa CA, Hernandez-Ramos R, et al. mHealth APP using machine learning to increase physical activity in diabetes and depression: clinical trial protocol for the DIAMANTE study. BMJ Open 2020;10:e034723. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-034723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hill NR, Arden C, Beresford-Hulme L, et al. Identification of undiagnosed atrial fibrillation patients using a machine learning risk prediction algorithm and diagnostic testing (PULsE-AI): study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Contemp Clin Trials 2020;99:106191. 10.1016/j.cct.2020.106191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yao X, McCoy RG, Friedman PA, et al. Ecg AI-Guided screening for low ejection fraction (Eagle): rationale and design of a pragmatic cluster randomized trial. Am Heart J 2020;219:31–6. 10.1016/j.ahj.2019.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yao X, Rushlow DR, Inselman JW. Artificial intelligence-enabled electrocardiograms for identification of patients with low ejection fraction: a pragmatic, cluster-randomized clinical trial. Nat Med 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nevin L, PLOS Medicine Editors . Advancing the beneficial use of machine learning in health care and medicine: toward a community understanding. PLoS Med 2018;15:e1002708. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ravi D, Wong C, Deligianni F, et al. Deep learning for health informatics. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform 2017;21:4–21. 10.1109/JBHI.2016.2636665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hae H, Kang S-J, Kim W-J, et al. Machine learning assessment of myocardial ischemia using angiography: development and retrospective validation. PLoS Med 2018;15:e1002693. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rodriguez-Ruiz A, Lång K, Gubern-Merida A, et al. Stand-Alone artificial intelligence for breast cancer detection in mammography: comparison with 101 radiologists. J Natl Cancer Inst 2019;111:916–22. 10.1093/jnci/djy222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McKinney SM, Sieniek M, Godbole V, et al. International evaluation of an AI system for breast cancer screening. Nature 2020;577:89–94. 10.1038/s41586-019-1799-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Siontis KC, Noseworthy PA, Attia ZI, et al. Artificial intelligence-enhanced electrocardiography in cardiovascular disease management. Nat Rev Cardiol 2021;18:465–78. 10.1038/s41569-020-00503-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Siontis KC, Yao X, Pirruccello JP, et al. How will machine learning inform the clinical care of atrial fibrillation? Circ Res 2020;127:155–69. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.316401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Setting guidelines to report the use of AI in clinical trials. Nat Med 2020;26:1311. 10.1038/s41591-020-1069-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wu E, Wu K, Daneshjou R, et al. How medical AI devices are evaluated: limitations and recommendations from an analysis of FDA approvals. Nat Med 2021;27:582–4. 10.1038/s41591-021-01312-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hernandez-Boussard T, Bozkurt S, Ioannidis JPA, et al. MINIMAR (minimum information for medical AI reporting): developing reporting standards for artificial intelligence in health care. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2020;27:2011–5. 10.1093/jamia/ocaa088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liu X, Rivera SC, Moher D, et al. Reporting guidelines for clinical trial reports for interventions involving artificial intelligence: the CONSORT-AI extension. BMJ 2020;370:m3164. 10.1136/bmj.m3164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rivera SC, Liu X, Chan A-W, et al. Guidelines for clinical trial protocols for interventions involving artificial intelligence: the SPIRIT-AI extension. BMJ 2020;370:m3210. 10.1136/bmj.m3210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Siontis KC, Siontis GCM, Contopoulos-Ioannidis DG, et al. Diagnostic tests often fail to lead to changes in patient outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol 2014;67:612–21. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Collins GS, Dhiman P, Andaur Navarro CL, et al. Protocol for development of a reporting guideline (TRIPOD-AI) and risk of bias tool (PROBAST-AI) for diagnostic and prognostic prediction model studies based on artificial intelligence. BMJ Open 2021;11:e048008. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-048008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.DECIDE-AI Steering Group . DECIDE-AI: new reporting guidelines to bridge the development-to-implementation gap in clinical artificial intelligence. Nat Med 2021;27:186–7. 10.1038/s41591-021-01229-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sounderajah V, Ashrafian H, Golub RM, et al. Developing a reporting guideline for artificial intelligence-centred diagnostic test accuracy studies: the STARD-AI protocol. BMJ Open 2021;11:e047709. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-047709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sounderajah V, Ashrafian H, Rose S, et al. A quality assessment tool for artificial intelligence-centered diagnostic test accuracy studies: QUADAS-AI. Nat Med 2021;27:1663–5. 10.1038/s41591-021-01517-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Collins R, Bowman L, Landray M, et al. The magic of randomization versus the myth of real-world evidence. N Engl J Med 2020;382:674–8. 10.1056/NEJMsb1901642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Califf RM, Zarin DA, Kramer JM, et al. Characteristics of clinical trials registered in ClinicalTrials.gov, 2007-2010. JAMA 2012;307:1838–47. 10.1001/jama.2012.3424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Perakslis E, Ginsburg GS. Digital Health-The need to assess benefits, risks, and value. JAMA 2021;325:127–8. 10.1001/jama.2020.22919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjhci-2021-100466supp001.pdf (557.3KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information. Not applicable.