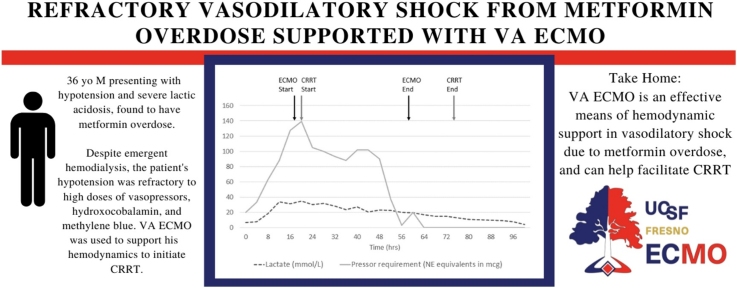

Graphical abstract

Keywords: Metformin, Poisons, Vasoplegia, Lactic acidosis, Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

Highlights

-

•

Metformin overdose can lead to vasodilatory shock refractory to medical management.

-

•

Extracorporeal circulatory support with venoarterial ECMO is an effective way to manage profound shock associated with metformin overdose.

-

•

We report the highest recorded serum metformin level in the literature to date.

Abstract

Metformin overdose may result in vasodilatory shock, lactic acidosis and death. Hemodialysis is an effective means of extracorporeal elimination, but may be insufficient in the shock setting. We present a case of a 39 yo male who presented with hypotension, coma, hypoglycemia, and lactate of 6.5 mmol/L after ingesting an unknown medication. Metformin overdose was suspected, and he was started on hemodialysis. He developed profound vasoplegia refractory to high doses of norepinephrine, vasopressin, epinephrine and phenylephrine. Venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA ECMO) was initiated and he had full recovery. Serum analysis with high resolution liquid chromatography mass spectrometry revealed a metformin level of 678 μg/mL and trazodone level of 2.1 μg/mL. This case is one of only a handful of reported cases of metformin overdose requiring ECMO support, and we report the highest serum metformin levels in the literature to date. We recommend early aggressive hemodialysis and vasopressor support in all suspected cases of metformin toxicity as well as VA ECMO if refractory to these therapies.

Objective

We present a case of vasodilatory shock secondary to metformin overdose requiring venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA ECMO) support. This case is one of only a handful of reported cases of metformin overdose requiring ECMO support, and we report the highest serum metformin levels in the literature to date.

Data sources

University of San Francisco, Fresno.

Study design

Case report.

Data extraction

Clinical records and high resolution liquid chromatography mass spectroscopy analysis.

Data synthesis

None.

Conclusions

Venoarterial ECMO provided an effective means of hemodynamic support for a patient with severe metformin toxicity.

1. Introduction and relevance

We present a case of vasodilatory shock secondary to metformin overdose requiring venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA ECMO) support with complete symptom resolution. This case is one of only a few reported cases of metformin overdose requiring ECMO support, and we report the highest serum metformin levels in the literature to date.

2. Case

Written consent for the publication of this case report was obtained.

A 36-year-old male presented to the emergency department (ED) with hypotension and altered mental status. Emergency medical services (EMS) reported an ingestion of an unknown quantity of medication, possibly metformin. The patient’s initial systolic blood pressure was 70 mmHg and his heart rate was 90 beats per minute. He was hypothermic to 32 °C. He was lethargic, with an initial Glasgow coma scale of 10. His skin was dry, and his pupils were mid-size, equal and reactive. There were no focal neurologic findings, hypertonicity, or clonus. At the time of his initial presentation, the exact timing of ingestion, substances ingested, and amounts of substances ingested were unclear. An empty pill bottle was found with the patient, which had a partially legible label stating the previous contents were expired metformin. The patient was unable to provide any history regarding the ingestion. We were unable to reach family or friends to gather more information regarding the ingestion. Volume resuscitation was initiated to support the patient’s blood pressure while labs and more data were obtained.

Initial labs were pertinent for a lactic acidosis of 6.5 mmol/L and hyperkalemia of 6.0 mmol/L. Transaminase, troponin, and creatine kinase serum levels were normal. Serum acetaminophen and salicylate levels were undetectable. The patient’s initial pre-hospital blood glucose was normal at 167 mg/dl. While in the ED, he developed delayed hypoglycemia with a blood glucose of 27 mg/dl. The hypoglycemia was treated with dextrose and octreotide. An acute dialysis catheter was placed. and hemodialysis was initiated emergently. Due to concern for severe metformin toxicity, dialysis was started 3.5 h after ED arrival. Despite this, the patient developed progressively worsening hypotension requiring a norepinephrine drip, as well as worsening mental status and lactic acidosis to 18 mmol/L.

The patient was admitted to the medical intensive care unit, where he was intubated for worsening altered mental status and shock. He rapidly developed profound vasoplegia refractory to high doses of norepinephrine, vasopressin, epinephrine and phenylephrine. Echocardiography revealed normal left ventricular and right ventricular function. The patient received multiple bicarbonate pushes, as well as a bicarbonate drip. He was also treated with hydroxocobalamin 5 gm intravenously, due to a concern for possible cyanide toxicity, though cyanide levels were later normal and this medication did not have any clinical effect. He received methylene blue 2 mg/kg which transiently improved his blood pressure. Continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) was attempted, but the patient was unable to tolerate CRRT hemodynamically, despite significant vasopressor support and methylene blue. At that point, the intensive care team and medical toxicologist decided that VA ECMO support would provide the best opportunity for the patient to recover. Prior to cannulation, the patient’s pH on an arterial blood gas was 7.05 with a PaCO2 of 19 mmHg and a lactate of 33.8 mmol/L.

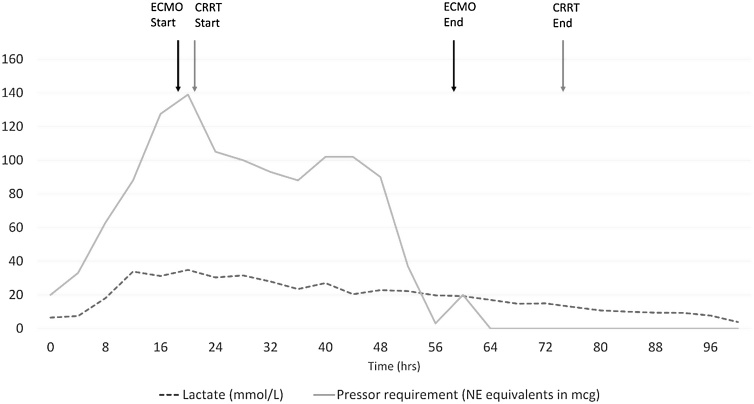

The patient was taken to the hybrid operating room, where he was peripherally cannulated for VA ECMO with a 25 F drainage cannula in the right femoral vein, and a 17 F return cannula in the left femoral artery. A 5 F distal perfusion cannula was placed with retrograde flow to the superficial femoral artery. Cannulation was performed using fluoroscopy without significant complications. The patient was initiated on VA ECMO support 19 h after ED arrival. The hemodynamic support from VA ECMO allowed initiation of CRRT. The patient’s shock resolved over the following 48 h, after which he was decannulated and was no longer requiring vasopressors (see Fig. 1). His lactic acid steadily improved to normal range over 96 h. The patient’s mental status improved, and he was extubated. He endorsed attempting to take his own life by ingesting metformin and trazodone. The patient was evaluated by psychiatry as an inpatient and was no longer suicidal. He was successfully discharged home 20 days after admission.

Fig. 1.

Vasopressor requirements and lactate concentration over time.

3. Laboratory analysis and results

Four serum samples at different time points and one urine sample on the admission day were analyzed using high resolution liquid chromatography mass spectrometry to identify over 5000 xenobiotics including all known diabetic hypoglycemic drugs. Metformin and trazodone were the only drugs identified. In addition, we specifically quantitated metformin, trazodone and its metabolite mCPP. Metformin concentration quantitation was performed on a QTRAP 4500 LC–MS/MS system (SCIEX, Redwood City, CA). Chromatography separation was done on a Phenomenex Kinetex C18- column (50 × 3.00 mm ID, 2.6 μm) with a Shimadzu Prominence LC-20ADXR system followed by electrospray ionization in positive mode. Metformin was detected using two multiple reaction monitoring transitions (130.0 -> 60.0 and 71.1) and calculated ion ratio. Metformin-d6 was used as an internal standard. Serum samples were prepared by protein precipitation with acetonitrile in conjunction with Hybrid SPE phospholipid removal plates, and urine samples were diluted at a 1:5 dilution. All the samples were diluted 1:20 or 1:400 before injection. The method is linear from 2 to 2000 u g/mL (r2 > 0.9999) in serum and 2–10000 u g/mL (r2 > 0.9998) in urine. The concentrations of trazodone and mCPP were quantitated using a LC-HRMS method on a TripleTOF 5600 (SCIEX, Redwood City, CA) [1]. In addition, we also checked for sulfonylureas since they are a common cause of hypoglycemia. We didn’t detect sulfonylureas in the serum and urine samples with an LC–MS/MS method on QTRAP 4500 previously reported to detect the eight most common sulfonylureas, including the first generation (tolbutamide, chlorpropamide, tolazamide, acetohexamide) and the second generation (glipizide, glyburide, glimepiride, and gliclazide) drugs [2].

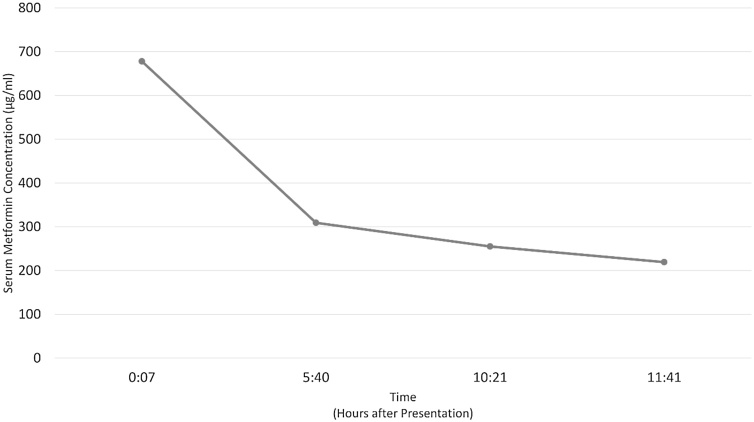

The patient’s initial serum metformin level was 678 μg/mL (Table 1, Fig. 2). His initial serum trazodone level was 2.1 μg/mL (Table 1). The trazodone metabolite mCCP was found in the patient’s urine, but not in his serum.

Table 1.

Serum and urine laboratory analysis.

|

Specimen (Hours after presentation) |

Metformin (μg/mL) | Trazodone (μg/mL) |

|---|---|---|

| Serum (00:07) | 678 | 2.1 |

| Serum (05:40) | 309 | 2.4 |

| Serum (10:21) | 255 | 1.1 |

| Serum (11:41) | 219 | 0.8 |

| Urine | 2224 | 3.6 |

Fig. 2.

Metformin concentration over time.

4. Discussion

Metformin is a biguanide antidiabetic medication well known to cause hyperlactatemia and metabolic acidosis in the setting of poor renal function or overdose [3]. Lactate levels associated with metformin toxicity previously described in the literature range from 10 to 40 mmol/L [[4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9]]. Our patient’s peak lactate was 33.8 mmol/L. Severe lactic acidosis occurs primarily due to inhibition of complex I in the electron transport chain, impairing oxidative phosphorylation and thus the ability to recycle H + from ATP hydrolysis [10].

Metformin can cause both severe hyperglycemia [9] and hypoglycemia in massive overdose [11]. In this case, profound hypoglycemia was observed. Severe metformin toxicity may require aggressive treatment with glucose, alkalinization, and extracorporeal methods for elimination; intermittent hemodialysis or continuous renal replacement therapy. Emergent hemodialysis has been recommended for patients with lactic acid > 20 mmol/L, pH less than or equal to 7.0, shock not responding to other therapies, and altered mental status [12].

The patient’s presenting serum metformin level of 678 μg/mL is the highest recorded serum metformin level reported in the literature to date. The previous highest level in both survivors and decedents was reported as 350 μg/mL [13]. Previous metformin concentrations in fatal overdoses are reported at a range of 42−188 μg/mL [14,15]. Metformin concentrations in survivors are reported between 0.3−350 μg/mL [13,15]. One case series examining the correlation between metformin concentration and clinical outcome, found that markedly elevated concentrations do not reliably prognosticate death. There is no specific lethal dose of metformin and the variability seen in reported cases suggests that other patient factors may play a more significant role in mortality [16]. This patient was young and in good health prior to this event which may have played a role in his good outcome. In addition, aggressive extracoporeal elimination techniques were performed which contributed to his positive outcome.

Metformin is known to act on the vascular endothelium. A proposed mechanism for the refractory vasodilatation seen with metformin toxicity is an increase in nitric oxide synthase activity and increased nitric oxide bioreactivity [17]. In this case, methylene blue was given to help reverse the patient’s vasodilatory shock with transient improvement. Methylene blue as a rescue therapy in the setting of metformin toxicity has been previously described in the literature, though infrequently, and has been noted to improve hemodynamics [[18], [19], [20]]. As an inhibitor of nitric oxide synthase and a competitive inhibitor of nitric oxide, methylene blue reduces the responsiveness of the vasculature to cGMP-mediated vasodilators. Methylene blue has been used to help restore vascular tone in vasodilatory shock of various etiologies, including post-cardiac bypass vasoplegia [20,21].

VA ECMO support for metformin toxicity has been rarely described in the literature [12,[22], [23], [24]]. Metformin levels are available for two of these prior cases, reported as 39 and 222 μg/mL. These patients required 9 and 7 days of VA ECMO support, respectively [23]. VA ECMO support for vasodilatory shock, as opposed to purely cardiogenic shock, has been described in other toxicities. One such example is dihydropyridine overdose [[25], [26], [27]]. A review of 104 cases of cardiovascular shock secondary to poisoning supported with VA ECMO, found that the majority had significant improvement in metabolic, hemodynamic and ventilatory parameters within 24 h [28]. VA ECMO can be considered at experienced centers for acutely poisoned patients with persistent shock after adequate volume resuscitation and appropriate doses of vasopressor and inotropic agents. Other methods of mechanical circulatory support such as intraaortic balloon pump or percutaneous left ventricular assist device (Impella) can be considered depending on availability and expertise of the treating center [29,30]. In this case, VA ECMO was used successfully and was associated with a good patient outcome. Overall, evidence for the use of VA ECMO for hemodynamic support in acutely poisoned patients is growing and is associated with relatively short ECMO runs and good outcomes. The most frequently encountered complications are bleeding and limb ischemia [31].

Based on this case report and our review of the literature, we recommend first recognizing metformin toxicity early: in the unknown critically ill patient often the only clue is a lactic acidosis without obvious causes such as septic or hypovolemic shock. Then, we recommend treating metformin overdose patients aggressively with rapid hemodialysis, vasopressor support, and initiating VA ECMO if refractory to the aforementioned treatments.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, we present a case of profound vasodilatory shock and lactic acidosis from metformin overdose which was refractory to medical therapy and successfully supported with VA ECMO.

Funding

This study was done without any financial support.

Address for re-prints (will not order)

UCSF Fresno Department of Emergency Medicine, 155 N Fresno St, Fresno, CA 93701, United States.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Handling Editor: Dr. Aristidis Tsatsakis

Footnotes

The work was performed at the University of San Francisco, Fresno.

References

- 1.Colby J.M., Thoren K.L., KL Lynch. Suspect screening using LC-QqTOF is a useful tool for detecting drugs in biological samples [Internet] J. Anal. Toxicol. 2018;42 doi: 10.1093/jat/bkx107. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29309651/ [cited 2020 Dec 9] Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang H.S., Wu A.H., Johnson-Davis K.L., et al. Development and validation of an LC-MS/MS sulfonylurea assay for hypoglycemia cases in the emergency department [Internet] Clin. Chim. Acta. 2016;454:130–134. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2016.01.007. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26790752/ Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kruse Ja. Metformin-associated lactic acidosis [Internet] J. Emerg. Med. 2001;20 doi: 10.1016/s0736-4679(00)00320-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11267815/ [cited 2020 Dec 9] Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kopec K.T., Kowalski M.J. Metformin-associated lactic acidosis (MALA): case files of the Einstein Medical Center medical toxicology fellowship [Internet] J. Med. Toxicol. 2013;9 doi: 10.1007/s13181-012-0278-3. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23233435/ [cited 2020 Dec 9] Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guo P.Y., Storsley L.J., SN Finkle. Severe lactic acidosis treated with prolonged hemodialysis: recovery after massive overdoses of metformin [Internet] Semin. Dial. 2006;19 doi: 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2006.00123.x. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16423187/ [cited 2020 Dec 9] Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dell’Aglio D.M., Perino L.J., Todino J.D., et al. Metformin overdose with a resultant serum pH of 6.59: survival without sequalae [Internet] J. Emerg. Med. 2010;39 doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2007.09.034. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18343080/ [cited 2020 Dec 9] Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gjedde S., Christiansen A., Pedersen S.B., et al. Survival following a metformin overdose of 63 g: a case report [Internet] Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2003;93 doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0773.2003.930207.x. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12899672/ [cited 2020 Dec 9] Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Von Mach M.A., Sauer O., SW L. Experiences of a poison center with metformin-associated lactic acidosis [Internet] Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes. 2004;112 doi: 10.1055/s-2004-817931. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15127322/ [cited 2020 Dec 9] Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suchard J.R., Grotsky T.A. Fatal metformin overdose presenting with progressive hyperglycemia [Internet] West. J. Emerg. Med. 2008;9 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19561734/ [cited 2020 Dec 9] Available from: [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang G.S., Hoyte C. Review of biguanide (metformin) toxicity [internet] J. Intensive Care Med. 2019;34 doi: 10.1177/0885066618793385. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30126348/ [cited 2020 Dec 9] Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al-Abri S.A., Hayashi S., Thoren K.L., et al. Metformin overdose-induced hypoglycemia in the absence of other antidiabetic drugs [Internet] Clin. Toxicol. 2013;51 doi: 10.3109/15563650.2013.784774. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23544622/ [cited 2020 Dec 9] Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Calello D.P., Liu K.D., Wiegand T.J., et al. Extracorporeal Treatment for Metformin Poisoning: Systematic Review and Recommendations From the Extracorporeal Treatments in Poisoning Workgroup. Crit. Care Med. 2015;43:1716–1730. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.North American Congress of Clinical Toxicology (NACCT) Abstracts 2018. Clin. Toxicol. 2018;56:912–1092. doi: 10.1080/15563650.2018.1506610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bonsignore A., Pozzi F., Fraternali Orcioni G., et al. Fatal metformin overdose: case report and postmortem biochemistry contribution. Int. J. Legal Med. 2014;128:483–492. doi: 10.1007/s00414-013-0927-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dell’Aglio D.M., Perino L.J., Kazzi Z., et al. Acute metformin overdose: examining serum pH, lactate level, and metformin concentrations in survivors versus nonsurvivors: a systematic review of the literature. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2009;54:818–823. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lalau J.D., Race J.M. Lactic acidosis in metformin-treated patients. Prognostic value of arterial lactate levels and plasma metformin concentrations. Drug Saf. 1999;20:377–384. doi: 10.2165/00002018-199920040-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davis B.J., Xie Z., Viollet B., Zou M.H. Activation of the AMP-activated kinase by antidiabetes drug metformin stimulates nitric oxide synthesis in vivo by promoting the association of heat shock protein 90 and endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Diabetes. 2006;55(2):496–505. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.55.02.06.db05-1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Graham R.E., Cartner M., Winearls J. A severe case of vasoplegic shock following metformin overdose successfully treated with methylene blue as a last line therapy [Internet] BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2015-210229. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Plumb B., Parker A., P Wong. Feeling blue with metformin-associated lactic acidosis [Internet] BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-008855. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Höjer J., Westerbergh J., Edfeldt-Ugarph M., et al. [Methylene blue stopped metformin-associated lactic acidosis and refractory vasodilatation] Lakartidningen. 2013;110:1865–1866. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hosseinian L., Weiner M., Levin M.A., et al. Methylene Blue: Magic Bullet for Vasoplegia? Anesth. Analg. 2016;122:194–201. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000001045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen T., Zhu C., B Liu. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation with continuous renal replacement therapy to treat metformin-associated lactic acidosis: a case report. Medicine. 2020;99:e20990. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000020990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang Anna, Rai Ashish, Zavin Alexandra, Rizwan Marvi. Veno arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in a case of metformin induced metabolic acidosis. Chest. 2020;158:A786. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang G.S., Levitan R., Wiegand T.J., et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) for severe toxicological exposures: review of the toxicology investigators consortium (ToxIC) J. Med. Toxicol. 2016;12:95–99. doi: 10.1007/s13181-015-0486-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vignesh C., Kumar M., Venkataraman R., et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in drug overdose: a clinical case series. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 2018;22:111–115. doi: 10.4103/ijccm.IJCCM_417_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lindeman E., Ålebring J., Johansson A., et al. The unknown known: non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema in amlodipine poisoning, a cohort study. Clin. Toxicol. 2020;58:1042–1049. doi: 10.1080/15563650.2020.1725034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jentzer J.C., Vallabhajosyula S., Khanna A.K., et al. Management of refractory vasodilatory shock. Chest. 2018;154:416–426. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weiner L., Mazzeffi M.A., Hines E.Q., et al. Clinical utility of venoarterial-extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA-ECMO) in patients with drug-induced cardiogenic shock: a retrospective study of the Extracorporeal Life Support Organizations’ ECMO case registry. Clin. Toxicol. 2020;58:705–710. doi: 10.1080/15563650.2019.1676896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Lange D.W., Sikma M.A., J Meulenbelt. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in the treatment of poisoned patients. Clin. Toxicol. 2013;51:385–393. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2013.800876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laes J.R., Olinger C., Cole J.B. Use of percutaneous left ventricular assist device (Impella) in vasodilatory poison-induced shock. Clin. Toxicol. (Phila) 2017;55(9):1014–1015. doi: 10.1080/15563650.2017.1335870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Upchurch C., Blumenberg A., Brodie D., MacLaren G., Zakhary B., Hendrickson R.G. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation use in poisoning: a narrative review with clinical recommendations. Clin. Toxicol. (Phila) 2021;59(10):877–887. doi: 10.1080/15563650.2021.1945082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]