Abstract

Policy Points.

Health actors can use the law more strategically in the pursuit of health and equity by addressing governance challenges (e.g., fragmented and overlapping mandates between health and nonhealth institutions), employing a broader rights‐based discourse in the public health policy process, and collaborating with the access to justice movement.

Health justice partnerships provide a road map for implementing a sociolegal model of health to reduce health inequities by strengthening legal capacities for health among the health workforce and patients. This in turn will enable them to resolve health issues with legal solutions, to dismantle service silos, and to drive systemic policy and law reform.

Context

In the field of public health, the law and legal systems remain a poorly understood and substantially underutilized tool to address unfair or unjust societal conditions underpinning health inequities. The aim of our article is to demonstrate the value of expanding from a social model of health to a sociolegal model of health and empowering health actors to use the law more strategically in the pursuit of health equity.

Methods

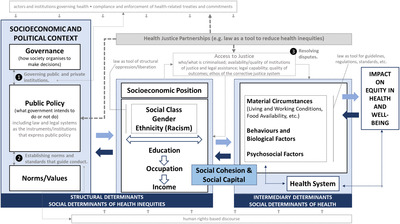

We propose a modified version of the framework for the social determinants of health (SDoH) equity developed by the 2008 World Health Organization Commission on the Social Determinants of Health by conceptually integrating the functions of the law as identified by the 2019 Lancet–O'Neill Institute Commission on Global Health and Law.

Findings

Access to justice provides a critical intersection between social models of public health and work in the justice fields. Addressing the inequities produced through the policies and institutions governing society unites the causes of those seeking to enhance access to justice and those seeking to reduce health inequities. Health justice partnerships (HJPs) are an example of a sociolegal model of health in action. Through the resolution of health issues with legal solutions at the individual level, the dismantling of service silos at the institutional level, and policy and law reform at the systemic level, HJPs demonstrate how the law can be used as a tool to reduce social and health inequities.

Conclusions

Greater attention to law as a tool for health creates space for increased collaboration among legal and health scholars, practitioners, and advocates, particularly those working in the areas of the social determinants of health and access to justice, and a promising avenue for reducing health inequities.

Keywords: social determinants of health, health inequities, law for health, medical‐legal partnership, health justice partnership

Law is a fundamentally human construction ubiquitous throughout society. 1 Some people have even gone as far as to conclude that “law so infuses daily life, is so much part of the mundane machinery that makes social life possible, that ‘law’ and ‘society’ are almost redundant.” 2 (p5) Although the public health community has tried to advance a social model of health and health equity, these efforts have largely been absent of any formal recognition of law and legal systems. 3

In 2008, the World Health Organization Commission on the Social Determinants of Health (henceforth the WHO Commission) released its final report synthesizing the evidence regarding how the social interactions, norms, and institutions that structure society affect population health. 4 In doing so, it reignited an understanding of health as a social phenomenon in an effort to promote greater equity and social justice in global health. 5 To guide its work, the WHO Commission developed a social determinants of health equity (SDoH) conceptual framework. But missing from the framework were law and legal systems.

A recent report from the Lancet–O'Neill Institute Commission on Global Health and Law (henceforth the Lancet Commission) positioned law as a determinant of health, demonstrating the contribution of law to health and health care. 6 At the core of the report was the naming of three functions of the law and four legal determinants of health (see Box 1). Even though the law “offers itself up as one of the sharpest instruments in our tool kits of resistance” against unfair or unjust societal conditions underpinning health inequities, 2 (p42) the authors observed that it remains poorly understood and substantially underutilized in the field of public health. 6

Box 1. Functions of the Law and Legal Determinants of Healtha

Three Functions of the Law

To govern public and private institutions.

To establish standards and norms that guide conduct.

To resolve disputes.

Four Legal Determinants of Health

Law can translate vision into action on sustainable development.

Law can strengthen governance of national and global health institutions.

Law can implement fair, evidence‐based health interventions.

Law emphasizes the importance of building legal capacities for health.

aAdapted from the Lancet‐O'Neill Institute Commission on Global Health and Law6

In this article we examine opportunities to integrate the observations of the Lancet Commission into the SDoH framework in order to demonstrate the value of expanding the framework from a social model to a sociolegal model of health. The article has three parts. The first briefly introduces the original SDoH framework as developed by the WHO Commission, as well as its aims and key features. We then incorporate these three functions of the law in global health into the framework and describe the opportunities that a sociolegal model of health would offer in supporting action on the social determinants of health. In the last part, we explore the integration of one of the legal determinants of health—building and strengthening the legal capacities for health—into the framework, using the case of health justice partnerships (HJPs), an initiative linking legal support with health services as a way of using the law as a tool to reduce health inequities. Our aim is to integrate more clearly the work of the Lancet Commission into that of the WHO Commission in order to empower health actors “to use law more strategically in the pursuit of health and equity.” 6 (p1858)

The Social Determinants of Health Framework

The WHO Commission's work has two key elements. First, it is not solely about improving health in the aggregate but also about reducing health inequities within and across populations. Health inequities refer to the “differences in health which are not only unnecessary and avoidable but, in addition, are considered unfair and unjust.” 7 (p220) Second, the WHO Commission emphasizes that health inequities are failures of governance to provide “fair access to basic goods and opportunities that condition people's freedom to choose among life plans they have reason to value.” 5 (p12) Addressing societally constructed health inequities is thus a defining feature of the WHO Commission's work.

The WHO Commission SDoH framework has three parts: (1) socioeconomic and political context, (2) socioeconomic position, and (3) intermediary determinants of health (see Figure 1). Each of the determinants in the framework are collectively the social determinants of health. These different elements, however, were introduced as an attempt to resolve some of the ambiguity about the dual meaning of this term. That is, the social determinants of health are the social processes that stratify the distribution of health determinants along a socioeconomic gradient, and the social determinants of health are the determinants of individual and population health. The former is captured by the interplay between socioeconomic and political contexts and socioeconomic position, subclassified as the structural determinants or the social determinants of health inequities. The latter is captured by the intermediary determinants of health—the subsequent effects of those structural determinants—subclassified as the social determinants of health. Here we refer to the subsets as the structural determinants and the intermediary determinants, and we use the social determinants of health language to refer to all determinants in the aggregate and in relation to health equity. 5

Figure 1.

Integrating Law as a Tool for Health Into the WHO Social Determinants of Health Framework [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

The socioeconomic and political contexts draw attention to structural factors such as the high‐level policy interventions that distribute wealth, power, and opportunities, in turn generating, configuring, and maintaining social hierarchies. This includes governance, defined by the United Nations Development Programme as a “system of values, policies and institutions by which society manages economic, political and social affairs through interactions within and among the state, civil society and private sector.” 8 (p287) It also captures the entirety of the public policy landscape (e.g., trade, labor, education, health care), which is shaped by the intersection of political, economic, and social forces as well as cultural and societal norms and values.

The second element of the framework focuses on the outcome of the socioeconomic and political contexts: the socioeconomic position. The socioeconomic position is a function of social stratifiers linked to systemic discrimination (e.g., social class, gender, race) and interrelated factors such as educational attainment, occupational status, and income level. Income is the single best indicator of material living standards and impacts health through “the conversion of money and assets into health enhancing commodities and services.” 5 (p30) Greater income inequality can also exert health‐damaging effects as a result of factors such as chronic stress for those at the bottom of the hierarchy or the erosion of social bonds, in addition to fewer material resources for individuals and communities. Educational attainment is an indicator of both the material and intellectual resources of the family of origin and also the individual's cognitive skills to receive health messaging and communicate with or access health services. Occupation, while strongly related to income, can exert additional health effects through the associated social status, stress, job control, and exposure to workplace hazards. Belonging to one or more marginalized groups affects every aspect of one's socioeconomic position and determines one's opportunities and experiences over the life course. 5

The third element of the framework is those intermediary determinants of health, that is, people's daily living conditions flowing from the social stratification induced by the structural determinants. Material circumstances include the determinants related to one's physical environment (e.g., quality and security of housing, neighborhoods, workplace) and the financial means to consume health‐promoting goods (e.g., healthy food, general living costs). Psychosocial factors include stressors like job strain or high debt, coping styles, and extent of control. Also captured here are behavioral and biological factors including genetic traits, age, and sex, and lifestyle factors such as tobacco and alcohol consumption. The health system is also positioned as an intermediary determinant through its capacity to provide equitable access to care and to promote intersectoral action to improve health. 5

Finally, the constructs of social cohesion and social capital are situated as both structural determinants of health inequity and intermediary determinants of health. Key theories of social capital drawn on by the WHO Commission include Bourdieu's class‐based theorization of economic, cultural, and social capital as resources in social struggles carried out in different social arenas or fields; 9 Putnam's categorization of social capital as norms and moral obligations, social values, and social networks; 10 and Woolcock and Sweetser's presentation of social capital as bonding, bridging, and linking capital: connections to people who are similar to you, connections to people who are not similar to you, and connections to people with power or influence, respectively. 11

From a Social Model of Health to a Sociolegal Model of Health

In this article, we follow the Lancet Commission in defining the law and legal systems to mean the “legal instruments such as statutes, treaties, and regulations that express public policy, as well as the public institutions (e.g., courts, legislatures, and agencies) responsible for creating, implementing, and interpreting the law.” 6 (p1857) Domestically, states hold the sovereign authority to develop law through constitutions, statutes, regulations, and case law, whereas internationally, various international institutions (e.g., WHO, the World Trade Organization) are imbued with lawmaking power in the form of treaties, customary international law, and general principles. 6

This article deviates from the Lancet report by employing the idea of “law for health” rather than “health law.” While the latter may evoke a narrower conception of the law (e.g., medical malpractice, international health regulations, right to health care), we believe that “law for health” suggests the broadest possible conceptualization of the law and legal systems that directly and indirectly affect health and health inequities in alignment with the SDoH framework. We have modeled this alteration in language on the shift from health governance to governance for health, which sought to expand the study of “institutions and processes of governance with an explicit health mandate” to those “which do not necessarily have explicit health mandates, but have a direct and indirect health impact.” 12 (pp2‐3)

The SDoH framework's greater integration of the law and legal systems draws on the existing overlap between the social determinants of the health equity movement in public health and the access to justice movement in the law. 3 , 13 Although terminology may differ between the two fields, both seek to address the complex range of social, structural, and institutional drivers of health and well‐being, and to use various tools (e.g., policy, law) to reduce inequities in social and health outcomes. Enabling access to justice is about more than just resolving legal problems; it is about reducing social inequities that produce health inequities, breaking vicious cycles that “create and compound poverty, undermine socioeconomic development, and contribute to broader social inequality.” 14 (p145)

The three functions of the law as laid out in the Lancet report 6 are (1) governing public and private institutions, (2) establishing norms and standards that guide conduct, and (3) resolving disputes. Next we explore the integration of each of these functions in the SDoH framework and the opportunities they open up to support action on the social determinants of health equity.

Governance of Public and Private Institutions

The first function of law addresses the governance of public and private institutions. The SDoH framework captures the concept of governance in its socioeconomic and political contexts. Although the SDoH framework acknowledges the interaction among each of the three components in the socioeconomic and political contexts (i.e., governance, public policy, norms, values), explicitly capturing the law demonstrates a crucial mechanism by which public policy influences governance, and in turn, governing bodies are able to influence public policy.

The Lancet Commission introduced a number of concrete challenges related to governance for health, including fragmented and overlapping mandates of actors and institutions (e.g., conflicts between the aims of the Ministry of Health to reduce sugar consumption and the Ministry of Agriculture to increase sugar production); weak monitoring, compliance, and enforcement of treaties and commitments (e.g., low state compliance with the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control due to the limited availability of incentives or sanctions); and the intersection of new entities with old governance regimes (e.g., the proliferation of nonstate actors in global health and participation in the WHO's governance processes).

By operationalizing some of these challenges, the Lancet Commission emphasizes the gap in knowledge and attention to the governance processes that drive law, policy, and norms for health. This opens areas for possible collaboration of legal and health scholars, practitioners, and advocates and should contribute to the production of new knowledge, as well as support the expansion of theories and methods for studying governance for health.

Establishing Norms and Standards That Guide Conduct

The second function of law, establishing norms and standards to guide conduct, also is found in the socioeconomic and political contexts of the WHO Commission framework. The Lancet Commission points to several avenues through which public policy, as expressed by law, forms the norms and standards that shape daily living conditions, or the intermediary determinants of health. These include the economic incentives or disincentives that establish norms and standards such as subsidies or taxes, which affect the supply and consumption of products with varying levels of healthfulness, as well as the guidelines for labeling, warnings, and marketing and advertising practices for such products; access to public goods though redistributive taxation, safety nets, and social welfare policies; quality of the built environment, from water and sanitation to livable spaces that foster community, safety, or physical activity; regulations pertaining to mandatory vaccinations or seat belts, or standards for health professionals, consumer goods, and pharmaceuticals; processes for litigation against businesses that sell unsafe or hazardous consumer products; as well as the removal of laws that act as barriers to health, such as laws banning the distribution of sterile injection equipment, abortion, or same‐sex behavior.

The law may also produce more indirect effects on health through its socioeconomic position when it acts as a tool that creates and normalizes structural oppression or liberation from that oppression. For example, the 1901 Immigration Restriction Act in Australia limited non‐British migration to Australia, launching more than seven decades of a White Australia policy, which institutionalized White Australian norms and values around race and culture. 15 Not until 1929 did Canada pass a law declaring that women were persons, thus allowing them to benefit more fully from available legal protections and rights. 16 Moreover, as of 2019, only 24 nations recognize marriage equality, with the majority of the world reserving for heterosexual couples the legal rights and privileges awarded by marriage. 17

The relationship between law and norms is, however, reciprocal, with the law and legal systems rooted in the norms and values of those who make and run them and, in turn, influencing future societal norms and values, including those shaping the conditions for health. The law is inextricably tied to one specific norm, namely, the notion of justice. While legal scholars and practitioners might assume that justice is synonymous with laws, legal institutions, and legal outcomes; for a nonlegal audience, many ideas about justice relate more to fairness, in either process or outcome. 18 Although the WHO Commission uses the language of social justice and the Lancet Commission discusses the idea as health with justice, the two commissions are aligned in an equity‐oriented vision of justice that seeks to reduce systematic differences in the distribution of goods and burdens in society producing health discrepancies that are unnecessary, avoidable, and unfair.

Arguably, one way in which the field of law and the social determinants of health use these ideas and norms of justice is through a broader rights‐based discourse, which recognizes the “equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family” as the “foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world” (United Nations General Assembly, Universal Declaration of Human Rights). In line with this, the work of both commissions is grounded in the progressive realization of a universal right to health. Williams and Hunt, as representatives of the health community in their response to the Lancet Commission, underscored the importance of a human rights frame. 19 They observed that in addition to being a set of legally binding obligations on states, human rights are “empowering entitlements to be claimed by people to address inequalities arising from power imbalances and inequities” 19 (p1783) and that it is this function that opens space for health actors to shape the law in ways that improve health and reduce health inequities. Accordingly, using this function of the law (i.e., to shape norms and standards), based on existing human rights legal architecture, could become a more frequently employed instrument in the health actor's toolkit.

Resolving Disputes (Access to Justice)

Finally, the third function of the law as described by the Lancet Commission is “a tool to resolve disputes between individuals, organisations, and governments.” 6 (p1864) One way to integrate this function of the law into the SDoH framework is to conceive of the idea of dispute resolution more broadly as access to justice and to position this as a determinant of health in and of itself. 20 Access to justice has been broadly defined as being “concerned with the ability of people to obtain just resolution of justiciable problems and enforce their rights, in compliance with human rights standards, if necessary, through impartial formal or informal institutions of justice and with appropriate legal support.” 21 (p24) Justiciable problems are defined as “problems that raise legal issues, whether or not this is recognised by those facing them, and whether or not lawyers or legal processes are invoked in any action taken to deal with them.” 21 (p58) According to the OECD, seven dimensions determine access to justice: the substance of the law, the availability of formal or informal institutions to secure justice, the quality of formal or informal institutions of justice, the availability of legal assistance, the quality of legal assistance, the quality of outcomes, and legal capability.

The concept of access to justice applies to both the criminal and civil justice systems. Criminal law addresses areas like violence against a person, theft or property damage, and other less serious offenses such as parking infringements. Criminal cases are brought by the government on behalf of society. 22 Civil law deals with relational disputes between individuals, organizations, and government agencies in which one party is seeking damages (financial remuneration) from another party in relation to their breach of civil law obligations. 22 Civil law is expansive and includes areas like family law, tenancy law, social security law, property law, labor law, immigration law, consumer law, and guardianship law. Despite the practical reasons to consider the criminal and civil systems separately, it is important to recognize that strong associations have been found between the experience of multiple disadvantages resulting in civil law issues and the social patterning of criminal offenses and victimization. 23

Accessing justice in the civil system is a complex and multifaceted process. One example is a landlord's civil obligations under the tenancy law to keep the premise in a reasonable state of repair, a breach of which could result in the development of mold. Frequently in civil law, a legal need represents an adverse social condition, such as an unmet basic need like housing, food, or health care, which can be remedied using existing laws, regulations, and policies 24 and which has direct causal links with health. 25 , 26 In this case, access to justice would require assessing the substance of the tenancy law itself and the balance of rights provided to the landlord and tenant; the availability, cost, and quality of the legal institutions and assistance accessible to the tenant to address this issue; the quality of the resolution reached; and the ability of the tenant to recognize the matter as a justiciable problem, to navigate the process for resolving it, and to understand the outcome. Most civil legal problems are resolved outside court but with the knowledge or threat of recourse to the court if they cannot be resolved otherwise. For example, family law disputes may be more likely to use mediation as a low‐cost option to produce more conciliatory outcomes. 27

Access to justice, the social determinants of health, and the criminal justice system are also intricately interwoven. A comprehensive review demonstrated that in fact, the social determinants of health and the social determinants of criminal behavior are very similar. 28 For example, studies in various countries have demonstrated that poverty increases the likelihood that a person will commit a crime, be apprehended for a crime, and be the victim of a crime. 29 , 30 Moreover, who and what becomes criminalized and who can afford justice in the criminal system are also socially patterned. 31 , 32

Many aspects of socioeconomic position have been shown to affect access to justice across the criminal justice system (e.g., arrest, adjudication, sentencing, parole) and pathways to offending and victimization. 33 , 34 , 35 The recent Black Lives Matter movement in the United States, for example, has gained international attention, as demonstrated in protests against police brutality and racially motivated violence against African Americans. The movement started in 2013 and peaked in 2020 following the death of George Floyd, a Black man killed by a White police officer who knelt on Floyd's neck for more than nine minutes while he was handcuffed lying face down. 36

In Australia, the systemic racism and oppression that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have endured for 250 years of colonialism have resulted in overrepresentation in the penal system. For example, in 2016 the detention rate for Indigenous children aged between 10 and 17 years was 26 times the rate for non‐Indigenous youth. 37 In addition to the broader implications for social capital and cohesion among such communities, 38 , 39 individual exposure to the penal system can produce negative feedback loops, resulting in lower educational attainment and wages due to time spent out of schooling and employment, fewer employment opportunities due to a criminal record, or threats to income security as a result of legal fees, fines, and incarceration. 40 , 41 All of this contributes to greater physical and mental health inequities. For example, intentional self‐harm was the leading cause of death for Indigenous persons between 15 and 34 years of age in 2017, more than three times that of non‐Indigenous Australians. 42 Many Aboriginal people in Australia have marched in solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement in the United States, bringing attention to the 432 Aboriginal deaths in custody since the 1991 Royal Commission Into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody, which has yet to be meaningfully implemented. 43 The Black Lives Matter Australia movement is continuing its protracted struggle against inequality that Indigenous Australians face, including inequality in the justice system. 44

For those in the penal system, the prison environment dictates their material circumstances and access to health care, the conditions of which vary widely based on different approaches to corrective justice, such as retribution (“eye for an eye”); rehabilitation (aligning the values and behaviors of offenders with the dominant values and behaviors of society); or specific and general deterrence (prevention). For example, whereas accounts of prisons in countries like Russia and Thailand describe “forced labor, decrepit living conditions and casual violence”; in Norway, guided by the principles of normality, humanity, and rehabilitation, prisons exist with “no walls or jail bars,” where “inmates raise sheep and cultivate organic strawberries.” 45

Within the SDoH framework, explicitly incorporating access into justice provides an opportunity to address more broadly “how different groups are integrated into—and excluded from—public institutions.” 46 (p1271) This could grow and develop institutional theory and analysis within the social determinants of health. Moreover, much as the health system can mediate the impacts of inequitable social conditions on equity in health and well‐being, the justice system sits upstream of health care, mediating the impact of social stratification and poor social conditions on the intermediary determinants of health. When possible, addressing legal/social needs before they become detrimental to health may alleviate both pressure from the health system and unnecessary suffering. Accordingly, we last look at one type of collaboration between health and legal professionals seeking to do just this.

Law as a Tool for Health: The Case of Health Justice Partnerships

The Lancet Commission introduced four legal determinants of health (see Box 1). In this discussion we focus on one legal determinant that underpins the rest: building and strengthening legal capacities as tools for health. This requires three key elements. The first is an effective legal environment of laws and processes that are available to be used. The second is a strong evidence base regarding the kinds of problems affecting health that have legal solutions. The third key element of legal capacity as a tool for health relies on capability or empowerment. Both individual and structural capability and empowerment are needed. Structurally, laws and legal processes need to provide a pathway to resolve health problems. But that capability alone does not guarantee that people will be able to use these pathways. Individually, people need to know that these pathways exist and to be empowered to use them. Building an understanding of how to use the law therefore becomes a critical step toward building or strengthening legal capacity as a tool for health. 47 This is the purpose of health justice partnerships HJPs (Box 2).

Box 2. Health Justice Partnerships

The Health Justice Partnership (HJP) embeds legal help into health care settings and teams in order to address legal problems that affect people's health. Many people are vulnerable to intersecting legal and health problems but are more likely to raise these problems in a trusted setting like a health service than to turn to a legal service for a solution. For instance, when someone's respiratory health or risk of infection is caused by the mold in their public or rental housing, the law provides a tool to compel landlords or housing authorities to meet their legal obligations to provide safe and hygienic housing. Whereas a health service might recognize that poor‐quality housing is the root cause of a patient's respiratory problems, the capability to use that legal tool often requires legal assistance.

Even though they are common across the community, legal problems are particularly prevalent among people experiencing social disadvantage. Legal problems have been found to cluster, for instance, around family breakdown, money issues, or poor‐quality housing, and they often coexist with everyday problems of life. Despite this prevalence of legal needs, many people take no action for their legal problems, and when they do seek advice, they are more likely to ask a nonlegal adviser, such as a health professional, than a lawyer. 48

HJPs operate by (1) embedding legal help in health services and teams to improve health and well‐being for individuals by directly providing services in places that they access, (2) assisting people and communities vulnerable to complex needs by supporting integrated service responses and redesigning service systems around client's needs and capabilities, and (3) supporting vulnerable populations by advocating for systemic change to policies affecting the social determinants of health. 49

Throughout the world, HJPs have consistently recognized the role of law and legal systems in shaping health and health inequities. In the United States, this model has been evolving since the late 1980s, driven by medical practitioners who recognized that they could not reduce preventable hospital admissions until they addressed the poor‐quality housing that was making many of their patients sick. 50 Legal scholars and practitioners in Australia and England observed this evolution in the United States and elsewhere internationally and translated it into their own communities and health care settings. 50 , 51 Consequently, HJPs have also had different points of entry to respective health settings. For instance, the Australian movement focuses on primary care and hospital settings, whereas the English approach has focused on locating legal help in general practitioners’ offices and developing referral pathways. 3 , 52

Identified briefly in the Lancet Commission using the US terminology, medical‐legal partnerships, these networks between health and legal services use law as a tool for health at individual, institutional, and systemic levels.

At the individual level, HJPs build on a tradition of publicly funded legal assistance that seeks to increase equity in access to justice. These partnerships provide a mechanism to utilize the skills of legal practitioners at the point that people are engaged with a health service, to access people's legal rights or entitlements or ensure that others meet their legal obligations. Integrating legal assistance into health care provides a way to address the underlying causes of health problems whose solutions lie beyond health care in legal remedies. The work of HJPs is transdisciplinary, informed by both what public health evidence identifies as health inequity and what sociolegal research describes as a lack of access to justice. These bodies of work inform the HJP approach to intersecting health and legal problems that impact some people disproportionately owing to their inequitable access to services or opportunities that would otherwise address or prevent these problems. Consequently, we argue that by enhancing legal capacity, HJPs provide a mechanism to improve equitable access to goods and opportunities that can in turn reduce health inequities.

Institutionally, HJPs operate between otherwise siloed service systems, that is, between the one‐on‐one care of health or legal assistance services to individuals accessing them for help and the social determinants of health. HJPs are reshaping institutional systems by offering a different way for services, practitioners, and the communities they support to work with and engage one another. In reshaping health and legal services to work together, HJPs recognize the interconnected nature of the health and legal problems that people face and try to put people at the center of service system responses to the impact of legal need on health outcomes. It is also at this level that HJPs build and strengthen legal capacity to use law as a tool for health, by placing the law and legal process in the suite of tools available to health services and by showing health practitioners and their patients how to use them.

HJPs provide a systematic opportunity to improve public policy to address the social determinants of individual and population health by identifying system failure through individual experiences and by harnessing the power of health and legal assistance practitioners working together as policy advocates. As Genn explained, “the accumulation of legal interventions on behalf of individuals to secure entitlements provides evidence of meso level policy failure and can contribute to the impetus for institutional policy change to address social determinants.” 3 (p179) This opportunity has been demonstrated most extensively in the United States, where public policy reform has become a central element to address health inequities in the work of these partnerships. Here the National Center for Medical‐Legal Partnership reports on 450 health organizations in medical‐legal partnerships in 49 states, 53 which now comprise a central element in the US approach to using law as a tool to address health injustice, particularly for marginalized patients and populations. The reforms achieved by these partnerships range from securing eligibility for health insurance among people affected by chronic conditions (specifically HIV/AIDS) 54 to the elimination of administrative burdens that place barriers in the way of mothers on low incomes finding food entitlements for their newborns. 55 In one example that points to the many different ways that law can be used successfully as a tool to advance health equity, the partnership model in the United States successfully reformed the federal government's approach to lead poisoning. This reform included adopting the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's definition of lead poisoning to federal law; mandating data sharing and reporting between housing authorities, public health departments, and the US Department of Housing and Urban Development to help identify children with elevated lead levels; and requiring that lead hazard risk assessments be conducted on all other assisted units in the same building where a child in a federally assisted housing unit tests positive for lead poisoning. 52

In England and Wales, collaborations between legal assistance and health services have been responding to social welfare problems since the early 1990s and have resulted recently in significant activity toward integrating health and legal support services in this field by both the government and the National Health Services. 33 In 2018, Beardon and Genn mapped 380 services working through a wide and varied range of connections between legal or welfare advice and health services, noting that “while some partnerships worked according to a model that was replicated across the country, most were unique arrangements built independently through local relationships.” 56 Health justice partnerships are also evolving in Canada across a range of health and legal assistance services, including a major hospital. 57

In Australia, the translation of the American model has reflected a commitment to systemic advocacy for structural outcomes since its early foundations. 50 , 51 Examples of structural policy reform involving HJPs in Australia are the federal government's commitment to establish a national plan to address elder abuse and a reform that was based on evidence and advocacy from HJPs and included a funding commitment to HJPs within that plan. 58 But to date, this component is still developing as a standard feature in what is both a young and evolving movement of HJPs in Australia. The second national census of HJPs found that only 18% had undertaken policy advocacy or law reform activities during the 2017/2018 financial year. 59

Conclusions

COVID‐19 brought renewed attention to the persistence of health inequities and the social patterning of experiences of the pandemic based on race, social class, gender, and immigration status. Although most people have experienced disruption and loss, these experiences have not been equal. 60 Structural and social determinants driving the experience of insecure and precarious work and overcrowded housing were visible drivers of the spread of infection among particular communities and undermined public health policies to isolate and distance. 61 Despite the opportunities to address, through the law, unfair or unjust societal conditions underpinning health inequities, it remains a poorly understood and substantially underutilized area in the field of public health. 6 In this article, we have sought to integrate the key features of the Lancet–O'Neill Institute Commission on Global Health and Law, namely, the functions of law, into the SDoH framework developed by the WHO Commission on the Social Determinants of Health. By progressing from a social model of health to a sociolegal model of health, we are seeking to build legal capacity among health actors and empower them to use the law strategically to reduce health inequities. We have also introduced the idea of law for health, rather than health law, to present the broadest possible conceptualization of law and legal systems that directly and indirectly affect health and inequity.

Integrating functions of the law throughout the SDoH framework presents new opportunities for research and action while also reinforcing lesser explored components of the model. Greater appreciation for the ways in which law can be a tool for health equity may draw attention to national and international institutions and the actors that shape them; the rules, regulations, and standards that guide daily living conditions; as well as laws that directly and indirectly stratify society by class, race, gender, religion, and sexuality in ways that reduce or widen social and health inequities. A more legally oriented approach may also help embed a human rights platform in the work of health actors and strengthen the rights‐based discourse as a foundation on which the research on and policy for SDoH are based. For example, arguments for addressing malnutrition in all its forms should not be limited to the negative externalities of overweight and obesity, or stunting and wasting, on economic development or productivity but rather should be justified first and foremost on the grounds that people have a right to adequate food and health. Research from a social determinants of health perspective could help normalize and embed rights‐based arguments and ensure that they are seen as equal to, or greater than, economic arguments.

Access to justice provides a critical intersection between social models of public health and work in the justice fields. Addressing the inequities produced through the policies and institutions governing society unites the causes of those seeking to enhance access to justice and those seeking to reduce health inequities. This intersection highlights not only shared goals but shared drivers as well. For example, poverty increases adverse health outcomes, experiences of multiple civil law issues, as well as the chance of being victimized and committing a crime. As a result, solutions are also shared, and coordinated action will reap rewards for all parties.

HJPs are an example of a sociolegal model of health in action and a way to build and strengthen legal capacities for health for the health workforce and patients. Through the resolution of health issues with legal solutions at the individual level, the dismantling of service silos at the institutional level, and policy and law reform at the systemic level, HJPs demonstrate how the law can be used as a tool to reduce social and health inequities. They provide a road map for scholars, policymakers, and practitioners on the power of integrating access to justice into the SDoH framework into shared drivers, shared goals, and shared solutions. Conceptual developments at the intersection of law and social models of public health like those in Figure 1, as well as real‐world illustrations, like HJPs, build and strengthen health actors’ legal knowledge and capacity and bring us closer to realizing the full potential of the law in addressing health inequity.

1.

Funding/Support: This study was conducted as a part of the Centre for Research Excellence in the Social Determinants of Health Equity (APP1078046) funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council.

Acknowledgments: We would like to acknowledge the contributions to and feedback on this article from Prof. David Best and our colleagues at the School of Regulation and Global Governance (RegNet) at the Australian National University.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: All authors completed the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. No conflicts were reported.

References

- 1. Friedman LM. The law and society movement. Stanford Law Rev. 1986;38:763‐780. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Calavita K. Invitation to Law & Society: An Introduction to the Study of Real Law. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Genn H. When law is good for your health: mitigating the social determinants of health through access to justice. Curr Leg Problems. 2019;72:159‐202. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Commission on Social Determinants of Health . Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Final report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. 2008. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/43943/9789241563703_eng.pdf?sequence=1. Accessed June 10, 2021.

- 5. Solar O & Irwin A. A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. 2010. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44489/9789241500852_eng.pdf. Accessed June 10, 2021.

- 6. Gostin LO, Monahan JT, Kaldor J, et al. The legal determinants of health: harnessing the power of law for global health and sustainable development. Lancet. 2019;393(10183):1857–1910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Whitehead M. The concepts and principles of equity and health. Health Promotion Int. 1991;6:217‐228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. United Nations Development Programme . Governance principles, institutional capacity and quality. In Towards Human Resilience: Sustaining MDG Progress in an Age of Economic Uncertainty. New York, NY: United Nations Development Programme; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bourdieu P. Le capital social. Actes de la Recherche en Sci. Soc. 1980;31:2‐3. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Putnam RD. Bowling alone: America's declining social capital. In: Culture and Politics. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan; 2000:223‐224. 10.1007/978-1-349-62965-7_12. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Woolcock M, Sweetser A. Bright ideas: social capital—the bonds that connect. ADB Rev. 2002;34:26‐27. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kickbusch I, Szabo MMC. A new governance space for health. Global Health Action. 2014;7:23507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Health Justice Australia . The rationale for health justice partnership: why service collaborations make sense. 2018. https://www.healthjustice.org.au/wp‐content/uploads/2018/12/Health‐Justice‐Australia‐The‐rationale‐for‐health‐justice‐partnership.pdf. Accessed June 10, 2021.

- 14. Pleasence P, Balmer NJ. Justice & the capability to function in society. Daedalus. 2019:148:140‐149. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jayasuriya L, Walker D, Gothard J. Legacies of White Australia: Race, Culture and Nation. Crawley, Western Australia: University of Western Australia Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 16. White A. Persons case: a struggle for legal definition & personhood. Alberta History. 1999;47:2. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Polikoff ND, Bronski M. Beyond Straight and Gay Marriage: Valuing All Families Under the Law. Boston, MA: Beacon Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hurlbert M. Defining justice. In Hurlbert M, ed. Pursuing Justice: An Introduction to Justice Studies. Canada: Fernwood Publishing; 2018:9‐19. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Williams C, Hunt P. Health rights are the bridge between law and health. Lancet. 2019;393:1782‐1784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nobleman RL. Addressing access to justice as a social determinant of health. Health Law J. 2014;21:49‐74. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Organisation for Economic Co‐operation and Development. Legal needs survey and access to justice. 2019. https://www.oecd‐ilibrary.org/docserver/g2g9a36c‐en.pdf?expires=1592985780&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=B1AB3F6384BA4557D7853ACE121058E3. Accessed June 10, 2021.

- 22. State Library New South Wales. What the law deals with. Hot topics: Australian legal system. Ottawa, ON: Public Interest Advocacy Centre; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pleasence P, McDonald H. Crime in context: criminal victimisation, offending, multiple disadvantage and the experience of civil legal problems. Updating Justice 2013;33:1‐6. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lawton EM, Sandel M. Investing in legal prevention: connecting access to civil justice and healthcare through medical‐legal partnership. J Leg Med. 2014;35:29‐39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tischer C, Chen C‐M, Heinrich J. Association between domestic mould and mould components, and asthma and allergy in children: a systematic review. Eur Respir J. 2011;38:812‐824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tischer CG, Hohmann C, Thiering E, et al. Meta‐analysis of mould and dampness exposure on asthma and allergy in eight European birth cohorts: an ENRIECO initiative. Allergy. 2011;66:1570‐1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ezzell B. Inside the minds of America's family law courts: the psychology of mediation versus litigation in domestic disputes student article. Law Psycho. Rev. 2001;25:119‐144. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Caruso GD. Public Health and Safety: The Social Determinants of Health and Criminal Behavior. UK: ResearchersLinks Books; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sariaslan A, Larsson H, D'Onofrio B, Långström N, Lichtenstein P. Childhood family income, adolescent violent criminality and substance misuse: quasi‐experimental total population study. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;205:286‐290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Galloway TA, Skardhamar T. Does parental income matter for onset of offending? Eur J Criminology. 2010;7:424‐441. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jenness V. Explaining criminalization: from demography and status politics to globalization and modernization on JSTOR. Annu Rev Sociol. 2004;30:147‐171. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Reiman J, Leighton P. Rich Get Richer and the Poor Get Prison, The (Subscription): Ideology, Class, and Criminal Justice. New York, NY: Routledge; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Huebner BM, Bynum TS. The role of race and ethnicity in parole decisions. Criminology. 2008;46:907‐938. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Spohn C, Sample LL. The dangerous drug offender in federal court: intersections of race, ethnicity, and culpability. Crime Delinquency. 2013;59:3‐31. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sobol NL. Charging the poor: criminal justice debt and modern‐day debtors’ prisons. Md Law Rev. 2015;75:486‐540. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Buchanan L, Bui Q, Patel J K. Black lives matter may be the largest movement in U.S. history. New York Times. July 3, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Youth detention population in Australia 2016. https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/fe88e241‐d0a2‐4214‐b97f‐24e7e28346b6/20405.pdf.aspx?inline=true. Accessed June 10, 2021.

- 38. Jobes PC, Donnermeyer JF, Barclay E. A tale of two towns: social structure, integration and crime in rural New South Wales. Sociologia Ruralis. 2005;45:224‐244. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lafferty L, Treloar C, Chambers G, Butler T, Guthrie J. Contextualising the social capital of Australian Aboriginal and non‐Aboriginal men in prison. Soc Sci Med. 2016;167:29‐36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nilsson A. Living conditions, social exclusion and recidivism among prison inmates. J Scand Stud Criminology Crime Prev. 2003;4:57‐83. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Waldfogel J. The effect of criminal conviction on income and the trust “reposed in the workmen.” J Hum Resources. 1994;29:62‐81. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Intentional self‐harm in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. 2018. https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/by%20Subject/3303.0~2017~Main%20Features~Intentional%20self‐harm%20in%20Aboriginal%20and%20Torres%20Strait%20Islander%20people~10. Accessed June 10, 2021.

- 43. Allam L. “Deaths in our backyard”: 432 Indigenous Australians have died in custody since 1991. The Guardian. June 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Langton M. Why the black lives matter protests must continue: an urgent appeal by Marcia Langton. The Conversation. August 4, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Watling E. The shocking contrast between prisons around the world. Newsweek. August 3, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sternberg Greene S. Race, class, and access to civil justice. Iowa Law Rev. 2016;101:1263‐1321. [Google Scholar]

- 47. McDonald H, People J. Legal capability and inaction for legal problems: knowledge, stress and cost. Updating Justice. 2014;41:1‐11. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Coumarelos C, Macourt D, People J, et al. Legal Australia‐wide survey: legal need in New South Wales. Sydney, Australia: Law and Justice Foundation; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Forell S, Boyd‐Caine T. Service models on the health justice landscape; a closer look at partnership. 2018. http://file/C/Users/u1031451/Desktop/Health‐Justice‐Australia‐Service‐models‐on‐the‐health‐justice‐landscape.pdf. Accessed June 10, 2021.

- 50. Noble P. Advocacy‐health alliances: better health through medical‐legal partnership. 2012. http://lcclc.org.au/wp‐content/uploads/2012/02/AHA‐Report_General.pdf. Accessed June 10, 2021.

- 51. Gyorki L. Breaking down the silos: overcoming the practical and ethical barriers of integrating legal assistance into a healthcare setting. 2013. https://www.churchilltrust.com.au/media/fellows/Breaking_down_the_silos_L_Gyorki_2013.pdf. Accessed June 10, 2021.

- 52. Patients‐to‐policy story: keeping children safe from lead poisoning. Keeping Children Safe From Lead Poisoning. 2018. https://medical‐legalpartnership.org/mlp‐resources/keeping‐children‐safe‐from‐lead‐poisoning/. Accessed June 10, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 53. National Centre for Medical Legal Partnership. Medical‐legal partnerships across the U.S. National Centre for Medical Legal Partnership. http://medical‐legalpartnership.org/partnerships/. Accessed June 10, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 54. National Centre for Medical Legal Partnership. Ensuring people with chronic conditions maintain access to care. National Centre for Medical Legal Partnership. 2018. https://medical‐legalpartnership.org/chronic‐conditions/. Accessed June 10, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 55. National Centre for Medical Legal Partnership. Increasing nutritional supports for newborns. 2018. https://medical‐legalpartnership.org/increasing‐nutritional‐supports‐for‐newborns/. Accessed June 10, 2021.

- 56. Beardon S, Genn H. The health justice landscape in England & Wales. Social welfare legal services in health settings. 2018. https://www.ucl.ac.uk/access‐to‐justice/sites/access‐to‐justice/files/lef030_mapping_report_web.pdf. Accessed June 10, 2021.

- 57. Jackson SF, Miller C, Chapman LA, EL Ford‐Jones, Ghent E, Pai N. Hospital‐legal partnership at Toronto Hospital for Sick Children: the first Canadian experience. Healthcare Q. 2012;15:55‐61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Australian Government . National plan to respond to the abuse of older Australians (elder abuse) 2019–2023. 2019. https://www.ag.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020‐03/National‐plan‐to‐respond‐to‐the‐abuse‐of‐older‐australians‐elder.pdf. Accessed June 10, 2021.

- 59. Forell S, Nagy M. Joining the dots: 2018 census of the health justice landscape, Health Justice Australia. 2019. https://www.healthjustice.org.au/wp‐content/uploads/2019/10/Health‐Justice‐Australia‐Joining‐the‐dots.pdf. Accessed June 10, 2021.

- 60. Kawachi I. COVID‐19 and the “rediscovery” of health inequities. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2020;49:1415‐1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Henriques‐Gomes L. “We should not pretend everybody is suffering equally”: Covid hits Australia's poor the hardest. The Guardian. September 26, 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/australia‐news/2020/sep/27/we‐should‐not‐pretend‐everybody‐is‐suffering‐equally‐covid‐hits‐australias‐poor‐the‐hardest. Accessed June 10, 2021. [Google Scholar]