Abstract

Policy Points.

Since the Surgeon General’s report in 2000, multiple stakeholder groups have engaged in advocacy to expand access to oral health coverage, integrate medicine and dentistry, and to improve the dental workforce.

Using a stakeholder map across these three policy priorities, we describe how stakeholder groups are shaping the oral health policy landscape in this century. While the stakeholders are numerous, policy has changed little despite invested efforts and resources.

To achieve change, multiple movements must coalesce around common goals and messages and a champion must emerge to lead the way. The ongoing COVID‐19 pandemic and political changes due to the 2020 elections can open a window of opportunity to unite stakeholders to achieve comprehensive policy change.

The 2000 surgeon general's report identified the state of oral health in America as an issue of major concern, highlighting significant disparities among vulnerable populations and associations with overall health and social determinants. Subsequently in “A Call to Action” issued by the Surgeon General in 2003, one of the five suggested actions was to promote collaborations among dental, medical, and public health communities to effect policy change. 1 In the intervening years, many stakeholder groups devoted significant resources to enhance the nation's oral health. Many of these efforts focused on policy reforms and demonstration projects that would enable better integration of oral health with the health system. In 2018, the Roundtable on Health Literacy of the National Academies of Science and Medicine (NASEM) convened a workshop on integrating oral and general health. 2

A decade after the 2000 Surgeon General's report, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) was signed into law by the Obama administration. While the law was wide in scope, it maintained the division between medicine and dentistry and did little to reform oral health policies. Health policy experts have long called for expanding oral health services, bridging the divide between medicine and dentistry, and improving the current dental workforce model. 3 The Surgeon General's new report, to be released in 2020/2021, is also expected to focus on the integration of oral health and to stress the importance of changes in the oral health delivery system.

The novel coronavirus (COVID‐19) pandemic has brought primary and preventive care in the United States nearly to a halt and revealed persistent disparities in access to care. 4 The response to COVID‐19, however, offers an opportunity to transition oral health from its self‐imposed silo to a fully integrated component of the US health education, delivery, and finance systems. It is time for the oral health community to align its stakeholders and demand policy change that integrates oral health into our public and private health insurance systems as part of a comprehensive package of benefits that is consistent and sustainable for all.

Similarly, the results of the 2020 presidential and congressional elections are instrumental in shaping the health care agenda for the near future. Any policy reform, according to John Kingdon, comes about when problems, politics, and policies connect, helped by the consistent efforts of stakeholders and advocates. In this perspective, we look at the evolution of oral health policy, specifically in the past 20 years and highlight the current state of stakeholder activity through a map of their involvement in expanding coverage, integrating oral and medical care delivery, and improving the dental workforce. Moreover, we argue that the COVID‐19 pandemic has been a major disruption to the health system. Coupled with changes in the political landscape, it could provide a window of opportunity for comprehensive dental reform if stakeholders coalesce to demand action.

Stakeholder Involvement and Oral Health Reform

Oral Health Coverage

Stakeholder groups at the state and federal levels have attempted a piecemeal expansion of oral health coverage. Most of these attempts at policy change have focused on particular populations rather than universal reform. Some groups have thus made small steps forward, but the lack of a unified strategy among the stakeholders has allowed disparities to grow for others.

Medicaid, CHIP, and Health Exchanges

Because pediatric dental benefits are mandatory for Medicaid, children have better rates of dental coverage than adults do. For example, in 2016, 10% of children had no dental coverage, compared to 26% of adults between the ages of 18 and 64. 5 In 2009, the Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP) added a dental benefit to its portfolio of benefits in direct response to the death of Deamonte Driver and the failure of the health system for vulnerable children. 6 Pediatric dental benefits were also added as one of the ten essential health benefits (EHB) in health exchanges created by the Affordable Care Act. However, because the dental plans are not offered in conjunction with medical plans, consumers are not obligated or mandated to purchase them, affecting their uptake 5 Other inclusions in the exchanges, such as the dependent coverage provision for private insurance plans, while not mandated for dental plans, had a positive spillover effect on access to care for adults 26 years and younger who might receive coverage as part of a family plan. 7 As of July 2020, 47 states offered some adult dental benefit in Medicaid, but the coverage differs by state and may be severely limited or restricted to emergency services only. In addition, those states that expand Medicaid may choose not to expand dental services to their adult populations. 8 Medicaid coverage for dental services has also been prone to cuts in times of fiscal austerity. For example, adult dental benefits were cut back in California and Massachusetts following the US Great Recession of 2007‐2009. 9

National organizations have advocated for either offering more benefits in current Medicaid dental programs and/or expanding eligibility to additional populations. Advocacy for expanded coverage in Medicaid may be considered a state focus, although some national consumer health advocacy groups, such as Families USA and Community Catalyst, have been active in this area as well. 10 , 11 Similarly, the Children's Dental Health Project (CDHP) was instrumental in adding dental provisions to CHIP, making dental benefits as one of the ten essential health benefits, and prioritizing Medicaid coverage for pregnant women. 12 The DentaQuest Partnership for Oral Health Advancement (DentaQuest [recently renamed CareQuest Institute for Oral Health]) and Henry Schein Cares (the foundation arm of a dental insurance company and a health care products distributor, respectively) support these and other organizations’ efforts to expand Medicaid dental services. 13 A grant‐making goal for DentaQuest in 2020 was the expansion of publicly sponsored dental benefits at both the state and federal levels. 14

Medicare

A third of all Medicare enrollees receive limited dental benefits through Part C supplemental plans. Even so, access to dental benefits for older adults is limited, as dental services are not included in the federally sponsored Medicare Parts A or B programs. 15 The dental exclusion provision in Medicare Parts A and B bars payment when the primary purpose of the dental work pertains to the teeth and supporting structures. While providers may be reimbursed for dental procedures considered “medically necessary” (e.g., radiation therapy of the jaw), implementation of the provision is inconsistent and limited in scope and delivery. 16 Efforts have been made to include oral health services in Medicare law, most recently by including dental services in Part B as proposed by the late Rep. Elijah E. Cummings, called “Lower Drugs Cost now,” which won House approval in December 2019, though it is not expected to be advanced in the US Senate. 17

Championing the inclusion of oral health in Medicare involves a diverse group of organizations with expertise in legal and consumer advocacy, policy think tanks, and grant making. Families USA collaborated with Justice in Aging, the Medicare Rights Center, and the Center for Medicare Advocacy in a campaign to include a dental benefit in Medicare Part B. 18 Justice in Aging, a legal advocacy group fighting senior poverty, and the Center for Medicare Advocacy have been involved with designing what a potential dental benefit in Medicare might look like and how to legislate these services into the Medicare law. 19 Families USA has been active in communicating consumers’ oral health needs to Medicare to highlight the barriers to access for this population. 11 More recently, Families USA, along with AARP, Center for Medicare Advocacy, and other leading national organizations, has founded the Medicare Oral Health Coalition. 20 Besides their advocacy and grants for Medicaid dental benefits, DentaQuest and Henry Schein Cares have supported research, advocacy, and grassroots mobilization for a Medicare dental benefit. 14 , 21 The American Dental Hygienists Association (ADHA) has also been a vocal proponent of this work. 22

A parallel movement supports including dental services in Medicare for individuals with a medical necessity. A “medical necessity” is defined as a condition such as diabetes mellitus, heart disease, dementia, and stroke. Research has shown that regular periodontal cleanings for individuals with systemic conditions like diabetes may result in lower health care costs. 23 The Santa Fe Group (a think tank focused on improving overall health through oral health) and Pacific Dental Services (PDS) have lobbied Congress and garnered ideological support from 80 organizations, including the American Medical Association (AMA), for a dental benefit to be included in Medicare. 26 These efforts resulted in a joint statement in 2018 that was supported by major foundations like DentaQuest, Arcora, Henry Schein Cares, and the Dental Trade Alliance (DTA). 27 The National Association of Dental Plans (NADP), a voice of the dental benefit industry, has also publicly advocated for various models to include dental benefits in Medicare. 28

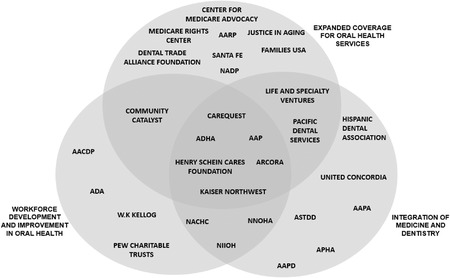

Adding a dental benefit to Medicare as either a basic package of preventive dental services or a set of dental services based on medical necessity has significant intellectual and financial support. Figure 1 shows a stakeholder map of the various organizations involved in expanding coverage for dental services.

Figure 1.

Organizations Categorized by 3 Topic Areas in National Oral Health Reform

Abbreviations: ADHA, American Dental Hygienists Association; AAP, American Academy of Pediatrics; AACDP, American Association of Community Dental Programs; ADA, American Dental Association; NADP, National Association of Dental Plans; NACHC, National Association of Community Health Centers; NNOHA, National Network of Oral Health Access; NIIOH, National Interprofessional Initiative on Oral Health; ASTDD, Association of State and Territorial Dental Directors; AAPA, American Academy of Physician Assistants; APHA, American Public Health Association; AAPD, American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry.

Integration of Medicine and Dentistry

The historical separation of medicine and dentistry has roots in the origin of the dental profession. Currently, this separation persists in medical and dental systems in education, delivery of care, and reimbursement. Since the 2000 Surgeon General's report, policy changes have been initiated to bridge the divide and promote integration between the two systems.

Changes in Payment and Delivery of Dental Care

In 2001, the George W. Bush administration increased community health center funding and encouraged the construction of new or the expansion of existing dental clinics. 29 The National Network for Oral Health Access (NNOHA), an organization representing safety‐net oral health providers, and the National Association of Community Health Centers worked to integrate dental services in community health centers through colocation, bidirectional referrals, integration of medical records, and comprehensive care management. 30 , 31 The Association of State and Territorial Dental Directors, along with the National Association of Chronic Disease Directors, disseminated resources on clinical integration from state dental programs. 32 Some delivery organizations, like Pacific Dental Services and Kaiser Northwest, are also working toward clinical integration in their settings. 33 , 34

In the early 2000s, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) actively engaged in experiments to improve health outcomes through innovations in care delivery and payment systems. The CMS State Innovation Models program enabled states to try different types of pilots, which evolved into accountable care organizations providing value‐based care with enhanced access to dental care. 35

Research on the cost and health impacts of these pilot programs has been funded by entities such as the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), the Agency for Health Research and Quality, and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. 36 Third‐party payers have begun to study the impact of integrated care. A 2014 study, funded by United Concordia using claims data suggested that integrating medical and dental care could save as much as $2,800 annually for Type 2 diabetics in the United States. 37 A wave of new benefits programs was designed by third parties hoping to improve health and reduce overall health expenditures by better integration of medical and dental care. 38 Further research is needed on the effectiveness of these plans.

Integration of Oral Health in Medical Education

The faculty at academic institutions and nonprofits like the National Interprofessional Initiative on Oral Health (NIIOH), funded by DentaQuest and Arcora, worked with the American Academy of Physician Assistants to educate providers on team‐based care in a patient's health home. Online curricula such as Smiles for Life have evolved to help oral health and primary care teams navigate interprofessional practices. 39 Similarly, the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry has collaborated with the American Academy of Pediatrics’ Oral Health Chapters to increase providers’ oral health education and create policy statements and related resources. 40

While stakeholder groups were coalescing to expand benefits, provider organizations were piloting ways to integrate medical and dental care and found promising evidence of improved health and lower costs. Although providers and payers have advocated for this change, they have not been united in their efforts. Figure 1 depicts the advocacy groups, professional associations, payers, and delivery organizations working on different facets of integration between medicine and dentistry.

Workforce Improvement and Development

According to the Health Resources and Services Administration, approximately 56 million Americans live in areas with a shortage of dental health professionals. 41 The data suggest that dental supplies, while adequate, are poorly distributed, resulting in a lack of access for people who need dental care the most: the poor, the elderly, rural residents, and racial and ethnic minorities. 42 Furthermore, many dentists choose to not treat Medicaid patients. 43 Because traditional models of care will not alleviate many of these barriers, the dental profession has started to create space for mid‐level providers, community dental health team members, and an expanded scope of practice for existing providers.

Dental Therapy

Mid‐level providers, known as “dental therapists,” provide preventive, restorative, and minor surgical procedures under the direct or indirect supervision of dentists. As of April 2020, 11 states had passed laws permitting the practice of dental therapy, and several states are actively considering legislation to authorize dental therapists. As part of its dental campaign, the Pew Charitable Trusts (PEW), an independent, nonprofit organization, has been leading and funding these efforts. 44 In this work, they have collaborated with other national organizations like Community Catalyst 45 and NNOHA. 46 Many national organizations have petitioned to legislate and operationalize dental therapists around the country. For example, NNOHA has encouraged pilots to study the efficacy of dental therapists in their settings. 47 The W.K. Kellogg Foundation has funded organizing and advocacy work by Community Catalyst and other training programs for dental therapy, 45 , 48 and the American Association of Community Dental Programs has used its annual symposium to promote dental therapy. 49 Additonaly, Community Catalyst co‐chairs a national coalition to garner support for dental therapy, along with other organizations like the National Indian Health Board Tribal Oral Health Initiative and The National Coalition of Dentists for Health Equity. 50

Expanded Role for Dental Hygienists

Dental hygienists are advocating for greater practice autonomy in several states. 51 There is significant variation across states in scope of practice of the dental hygiene profession. For example, dental hygienists have considerable independence in some states (e.g., Colorado) but are more constrained in others (e.g., Georgia). 52 Several states more recently have also expanded the scope of dental hygienists to use silver diamine fluoride (SDF) in community settings as a noninvasive method to control dental caries. 53 The American Dental Hygienists Association (ADHA) is at the forefront of expanding the roles and duties of dental hygienists across the 50 states and has undertaken legislative advocacy at the state and federal levels to provide dental hygienists more autonomy and to encourage integration of dental hygienists in innovative practice settings. 54 The ADHA, partnering with PEW, has also been a vocal supporter of dental therapy legislation in many states, including proposals that utilize the current dental hygiene infrastructure to develop a dental therapy program. 55 , 56

Community Dental Health Coordinator

In 2006, the American Dental Association (ADA) launched the Community Dental Health Coordinator (CDHC) program to provide community‐based prevention and care coordination for underserved communities. The ADA has championed this cause by helping train graduates in all 50 states and advocating for this model with primary care associations and third‐party payers. 57 The NNOHA has collaborated with the ADA to pilot the CDHC model in its network of community health centers. 58

Greater Participation from Primary Care Providers

The medical community has been encouraged by advocates to include oral health competencies in training and practice. For example, physicians can be reimbursed for putting fluoride varnish on teeth 59 and pilots are under way to encourage primary care providers to apply silver diamine fluoride as a preventive measure against caries. 60 Changes are needed, however, in the education, delivery, and reimbursement for these services. The promotion of interprofessional education and the expansion of primary care providers and oral health professionals who can address shortages in rural and other areas are increasing. These stakeholders and those working toward transforming oral health policies regarding benefits and service delivery should join forces to effect change at the national level in a meaningful and uniform way (see Figure 1).

A Road Map for Change

Though many organizations are working to reform national oral health policies, there is no clear leader or crosscutting agenda, and without them, no significant and sustainable policy change is likely. National consumer and aging organizations like Families USA, Center for Medicare Advocacy, Justice in Aging, and Medicare Rights Center 18 , 20 have been working to include a broad dental benefit in Medicare to provide access for older adults. However, a coalition of national presence has not actively lobbied for changes in Medicaid to require coverage of dental services for low‐income adults under the age of 65. Currently, Medicaid's dental coverage for low‐income adults is an option for state governments, resulting in a network of widely varied benefits on a state‐by‐state basis rather than nationally. 8 Even though state‐level advocates have been able to incrementally defend or expand dental benefits in their states, and DentaQuest has taken a leading role in advocating for legislation to expand dental benefits in all states, 14 a prominent national stakeholder coalition is also needed to champion this cause.

The dental therapy movement has gained support from multiple consumer advocates and foundations (PEW, Community Catalyst, and W.K. Kellogg Foundation) promoting access for underserved populations. 44 , 45 , 48 , 50 Although they have had some success, the movement has stalled at the state level because of state dental practice acts, payment policies, and opposition from organized dentistry. While initiatives aim to expand access by changing public benefits programs and offering innovative practice models, they have been unable to transcend silos to achieve consensus. Perhaps national diverse stakeholders, including consumer advocates, providers, and industry, need to, and have been unable to agree on, a common agenda.

The oral health stakeholder landscape is dynamic in both good and not‐good ways. For example, Oral Health America, the leading oral health advocacy organization established in 1955, ceased operation in early 2019. 61 Other organizations, such as CDHP, have been subsumed under larger organizations. 62 The resulting void may be filled by other entities, but the unsettled landscape, absent a dominant leader, hinders effective stakeholder mobilization on reform. A national champion that spans the policy spectrum is needed to drive these coalitions forward to effect meaningful change.

Lessons from the ACA

These structural barriers to effective advocacy are significant. Lessons from the legislative process leading to passage of the ACA may be instructive. Between 2008 and 2010, key reformers and advocates made a strategic choice to work with, rather than against, health system stakeholders such as the pharmaceutical industry and hospital and physician associations. 63 Critics of the 1993/1994 Clinton health reform effort cite the lack of support by key stakeholders as key to its failure. 64 In the legislative process for the ACA, major interest groups that had opposed past health reforms supported the bill. The American Medical Association, for example, which had opposed health reform, including the 1965 creation of Medicare and Medicaid, softened its stance during the Clinton era and fully supported passage of the ACA in 2010. 65

The American Dental Association (ADA) has unparalleled control over the licensure and regulation of dental care delivery, and its opposition to reform dampens the pace and enthusiasm to achieve progress. Also, major dental trade organizations (National Association of Dental Plans and Dental Trade Alliance), while involved in advocacy for coverage expansion, are not seen as leaders in this arena. The ADA has long and actively opposed reform of oral health coverage. In 1965, the ADA joined the AMA in opposing health legislation under the Social Security Act. 66 More recently, in contrast to other professional organizations like the American Dental Hygienists Association, the ADA opposed proposals to include an oral health benefit in Medicare. 67 In a letter in October 2019 to the House Ways and Means Committee, the ADA indicated an interest in working with Congress on an oral health policy for Medicare, but it has not publicly aligned itself with other advocacy groups active in this area. 68

The ADA and state dental associations oppose legislation to expand dental teams to include mid‐level providers such as dental therapists and advanced dental hygiene practitioners. 69 , 70 An example of this opposition can be found in 2006 when the ADA and the Alaska Dental Society filed a lawsuit against the Alaska Native Tribal Consortium, alleging that the first dental therapists certified by the Community Health Aide Program were practicing without a license. 71 The ADA's opposition reflects the feelings of its primary constituents. That is, many of the members of the largest professional association representing American dentists may oppose coverage, delivery, and workforce reform.

Some experts argue that the ADA, as an organization representing the dental profession, has the strongest ethical mandate to advance oral health, 72 particularly given the recent social unrest and increasing disparities during the COVID‐19 pandemic. The ADA could also engage in state and national debates about workforce models, benefits, and training. The pandemic has revealed the importance of public health and disparities in the United States, as vulnerable communities are suffering disproportionately from the virus. 73 The pandemic, along with the accompanying economic downturn and the 2020 national elections, could be an opportunity for oral health reform.

Potential Policy Window: COVID‐19 and the 2020 Elections

In mid‐April 2020, the ADA reported that approximately 19% of dental offices were closed and that 76% were open for emergency care only. 74 Although many began to reopen or expand care by July, as of mid‐April 2021, the ADA reported that nearly 40% of dental practices nationally are seeing lower patient volumes. 75 The pandemic has proved that dentistry, like other parts of the US health system, is not immune to external shocks. As a result, the ADA adopted a policy in October 2020 calling dentistry an “essential health service.” This policy, according to the ADA, is intended to make sure that patients have access to dental care when they need it, whether during the pandemic or a future crisis. 76

Deeming dental care as “essential” while failing to remove barriers to access displays the paradoxical nature of the ADA's position. The COVID‐19 pandemic is said to be the most unequal in modern US history and especially hurts low‐wage minority workers. 77 The downturn has further increased disparities in access to dental care. 78 Accordingly, organized dentistry must start to ask tough questions to find a more sustainable model to finance and deliver its services. Massive increases in unemployment and the loss of employer‐provided dental insurance caused by the pandemic demonstrate the need to expand public benefits for dental coverage. Although the closures of dental clinics and the loss of business were not related to the current delivery and financing of care, alternative payment models might have reduced the financial shock in a business model that so heavily relies on volume of services. This shows that in the future, growing numbers of dental practices can no longer rely on fee‐for‐service payments for profitable returns, thereby motivating public policymakers to be more open to efforts to seek alternative payment models of value‐based care. Expanding the workforce to mid‐level providers will not only help increase access to dental care but also allow practices reeling from financial losses to do so in a cost‐effective manner. Similarly, teledentistry, much like telemedicine, is here to stay. Teledentistry can provide continuity of care and triage patients to offices while optimizing providers’ time by matching patients’ needs to providers’ skills. 79

As dental clinics reopen post‐COVID‐19, they are testing for COVID‐19 and dentists can administer vaccines in multiple states. 80 , 81 This is an opportunity for dental and medical practices to collaborate to integrate care, and to stimulate integration of electronic health records and new referral pathways. In 2008, the Federation of American Hospitals, a national trade organization of for‐profit hospitals, supported and invested in health care reform because of the uncompensated care burden borne by hospitals. Universal coverage made good business sense to them. 65 Similarly, now the very constituents represented by organized dentistry, suffering from business losses, need to support reforms. The ADA plus dental trade organizations (NADP and DTA) can lead the way in lobbying for legislation and joining resources with foundations, payers, and advocacy groups active across the coverage, delivery, and workforce arenas (see Figure 1).

Based on the John Kingdon model, policy change occurs when problems, policies, and political streams converge at an opportune time. Accordingly, this pandemic presents a watershed moment for oral health stakeholders to support bold and comprehensive changes in how dental care is accessed and delivered. It also should cause dentists and the ADA to reconsider their past positions. The opportunities for innovation provided by the COVID‐19 crisis, along with changes in the political landscape, could connect these streams and lead to a shift in the status quo.

The implications of the 2020 national elections on such a policy change are uncertain. Because the Democrats hold majorities in both the House and Senate, we can expect moves toward more‐universal health coverage. Progressive legislators in the past have championed comprehensive oral health reform. Senator Bernie Sanders (I‐VT) cosponsored the Comprehensive Dental Reform Act in 2015, including amendments to Medicare and Medicaid, and adding oral health as an essential health benefit while expanding the role of mid‐level dentistry providers. 82 He also included comprehensive dental care in his Medicare for All plan. 83 While that legislation will not become reality anytime soon, the Democratic Party's health care agenda seems open to oral health reform and may become more expansive with time. Stakeholders need a unified coalition led by the ADA, dental trade organizations, and consumers to be responsive to upcoming changes and to ensure that oral health is well represented in future health care reform discussions.

Conclusion

While stakeholders work in disparate segments of oral health reform, COVID‐19 is forcing all of them to reimagine health care delivery. Patients, providers, and payers must work together to guarantee that all communities have access to care at the right time in the right way. Now is the moment to leverage the energy and resources of stakeholders who have been working on access, education, care delivery, and benefits to create a new paradigm for oral health in the United States. For comprehensive reform to succeed, the ADA needs to harness its energy at state and national levels to align and lead the different national stakeholder coalitions to advocate for policy changes. If the ADA does not take charge, change may continue to be slow and incremental. It is then even more imperative that other stakeholders unite under a singular agenda and continue pushing for reform that will enable access to essential oral health services for all Americans.

Funding/Support: None.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: All authors completed the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interes. Mr. Fuccillo reported that he is the vice president of the Santa Fe Group. Mr. Fuccillo is also a consultant and senior advisor to the CEO at the DentaQuest Partnership for Oral Health Advancement (recently renamed CareQuest Institute for Oral Health) and previously served as the chief mission officer and president at the DentaQuest Partnership for Oral Health Advancement.

Acknowledgments: We wish to thank the Harvard School of Dental Medicine Initiative to Integrate Oral Health and Medicine for its support. We also thank Dr. Calvin Rhoads and Ms. Maya Kiel for their research assistance. Finally, we thank Dr. Steven Geiermann for critically reviewing the manuscript.

References

- 1. US Department of Health and Human Services . National Call to Action to Promote Oral Health: a Public‐Private Partnership. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research; Spring; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Atchison KA, Rozier RG, Weintraub JA. Integration of oral health and primary care: Communication, coordination and referral. NAM Perspectives. 2018. 10.31478/201810e [DOI]

- 3. McDonough, JE . Might oral health be the next big thing? Milbank Q. 2016;94(4):720‐723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mehrotra A, Chernew M, Linetsky D, Hatch H, Cutler D. The impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on outpatient visits: a rebound emerges. New York, NY: Commonwealth Fund; 2019. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/2020/apr/impact‐covid‐19‐outpatient‐visits. Accessed June 22, 2019.

- 5. Children's Dental Health Project . Progress to build on: recent trends on dental coverage access. 2018. https://www.cdhp.org/blog/557‐progress‐to‐build‐on‐recent‐trends‐on‐dental‐coverage‐access. Accessed June 17, 2020.

- 6. Iglehart J. Dental coverage in SCHIP: the legacy of Deamonte Driver. Health Affairs Blog. January 30, 2009. 10.1377/hblog20090130.000496. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shane DM, Ayyagari P. Spillover effects of the affordable care act? Exploring the impact on young adult dental insurance coverage. Health Serv Res. 2015;50(4):1109‐1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Center for Health Care Strategies . Medicaid adult dental benefits: an overview. 2019. https://www.chcs.org/media/Adult‐Oral‐Health‐Fact‐Sheet_091519.pdf. Accessed June 17, 2020.

- 9. Snyder A, Kanchinadam K. Adult dental benefits in Medicaid: recent experiences from seven states. Portland, ME: National Academy for State Health Policy; 2015. https://www.nashp.org/adult‐dental‐benefits‐in‐medicaid‐recent‐experiences‐from‐seven‐states/. Accessed June 17, 2020.

- 10. Community Catalyst . Dental access project. 2020. https://www.communitycatalyst.org/initiatives‐and‐issues/initiatives/dental‐access‐project. Accessed June 17, 2020.

- 11. Families USA . Share your oral health story. 2020. https://familiesusa.secure.force.com/stories/yourstory?category=dental. Accessed June 17, 2020.

- 12. Edelstein B. More than 22 years of success & gratitude. 2019. https://www.cdhp.org/blog/699‐more‐than‐22‐years‐of‐success‐gratitude. Accessed June 22, 2020.

- 13. Children's Dental Health Project. Topics and resources. 2013. https://www.cdhp.org/resources/169‐about‐the‐children‐s‐dental‐health‐project. Accessed June 17, 2020.

- 14. CareQuest Institute for Oral Health. 2020 funding announcement. 2020. https://www.carequest.org/about/news/2020‐funding‐announcement%C2%A0. Accessed April 21, 2021.

- 15. Willink A, Reed NS, Swenor B, Leinbach L, DuGoff EH, Davis K. Dental, vision, and hearing services: access, spending, and coverage for Medicare beneficiaries. Health Aff. (Project Hope). 2020;39(2):297‐304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Center for Medicare Advocacy . Legal memorandum: statutory authority exists for Medicare to cover medically necessary oral health care. 2019. https://medicareadvocacy.org/medicare‐info/dental‐coverage‐under‐medicare/. Accessed June 17, 2020.

- 17. Library of Congress. H.R.3 , Elijah E. Cummings Lower Drug Costs Now Act. 2020. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th‐congress/house‐bill/3/text. Accessed June 17, 2020.

- 18. Families USA . Joint letter: consumer advocacy organizations urge senate to consider medical dental coverage following the passage of H.R.3. 2019. https://www.familiesusa.org/wp‐content/uploads/2019/12/Group‐Letter_Senate‐Medicare‐dental_final.pdf. Accessed July 17, 2020.

- 19. Justice in Aging . Adding a dental benefit to Medicare part B: frequently asked questions. 2019. https://www.justiceinaging.org/wp‐content/uploads/2019/11/Adding‐a‐Dental‐Benefit‐to‐Medicare‐Part‐B‐FAQs.pdf. Accessed June 17, 2020.

- 20. Families USA . Medicare oral health coalition. 2021. https://familiesusa.org/our‐work/medicare‐oral‐health‐coalition/. Accessed April 21, 2021.

- 21. Oakes D, Monopoli, M. Medicare dental benefit will improve health and reduce health care costs. Health Affairs Blog. February 28, 2019. 10.1377/hblog20190227.354079. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. American Dental Hygienists’ Association . Medicare dental bill introduced. 2019. https://www.adha.org/medical‐dental‐bill‐introduced. Accessed June 17, 2020.

- 23. Elani HW, Simon L, Ticku S, Bain PA, Barrow J, Riedy CA. Does providing dental services reduce overall health care costs? A systematic review of the literature. J Am Dent Assoc. 2018;149(8):696‐703.e692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. ProPublica . Lobbying by Santa Fe Group. 2020. https://projects.propublica.org/represent/lobbying/r/301024257. Accessed June 20, 2020.

- 25. ProPublica . Lobbying by Pacific Dental Services. 2020. https://projects.propublica.org/represent/lobbying/r/300943317. Accessed June 20, 2020.

- 26. Community statement on Medicare coverage for medically necessary oral and dental health therapies. 2018. https://dentallifeline.org/blog/dln‐joins‐80‐organizations‐in‐support‐of‐medicare‐coverage‐for‐medically‐necessary‐oral‐and‐dental‐health‐therapies/. Accessed June 22, 2020.

- 27. Santa Fe Group . Sponsors and supporters. 2020. https://santafegroup.org/about‐us/consensus‐statements/. Accessed April 20, 2021.

- 28. National Association of Dental Plans . Dental plans leaders urge congress to improve access to dental coverage via Medicare and marketplaces. 2019. https://www.globenewswire.com/news‐release/2019/06/05/1864863/0/en/Dental‐Plans‐Leaders‐Urge‐Congress‐to‐Improve‐Access‐to‐Dental‐Coverage‐via‐Medicare‐and‐Marketplaces.html. Accessed June 22, 2020.

- 29. Shi L, Lebrun LA, Tsai J. Assessing the impact of the Health Center Growth Initiative on health center patients. Public Health Rep. 2010;125(2):258‐266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. National Association of Community Health Centers. NACHC oral health activities. 2019. http://www.nachc.org/wp‐content/uploads/2019/03/Oral‐Health‐Activites‐One‐pager.pdf. Accessed June 17, 2020.

- 31. National Network for Oral Health Access. Program and initiatives. 2013. https://www.nnoha.org/programs‐initiatives/ipohccc/. Accessed June 17, 2020.

- 32. National Association of Chronic Disease Directors. NACDD's partnership with the association of state and territorial dental directors promotes oral health and chronic disease integration efforts. 2018. Accessed June 17, 2020.

- 33. Wright K. 2015 national Medicaid and CHIP oral health symposium . 2015. https://www.medicaiddental.org/files/FINAL%20Session%209‐%20Serota%20&%20Wright%20%20%20.pdf. Accessed June 22, 2020.

- 34. This Week in Health IT. Dental/medical integration with pacific dental leadership Steve Thorne and Dan Burke. 2020. https://www.thisweekhealth.com/dental‐medical‐integration‐with‐pacific‐dental‐leadership‐stephen‐thorne‐and‐dan‐burke/. Accessed June 22, 2020.

- 35. Chazin, S , Crawford, M. Oral health integration in statewide delivery system and payment reform. 2016. https://www.chcs.org/media/Oral‐Health‐Integration‐Opportunities‐Brief‐052516‐FINAL.pdf. Accessed June 17, 2020.

- 36. Many foundations award grants in oral health. Health Aff. (Project Hope). 2016;35(12):2340‐2341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jeffcoat MK, Jeffcoat RL, Gladowski PA, Bramson JB, Blum JJ. Impact of periodontal therapy on general health: evidence from insurance data for five systemic conditions. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(2):166‐174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Life and Specialty Ventures . Leading the charge to integrate dental and medical coverage. 2020. https://www.lsvusa.com/what‐we‐do/dental/thought‐leadership/. Accessed June 22, 2020.

- 39. National Interprofessional Initiative on Oral Health. Partners. 2020. http://www.niioh.org/content/partners. Accessed August 3, 2020.

- 40. American Academy of Pediatrics . Chapter oral health advocates. 2020. https://www.aap.org/en‐us/advocacy‐and‐policy/aap‐health‐initiatives/Oral‐Health/Pages/Chapter‐Oral‐Health‐Advocates.aspx. Accessed June 17, 2020.

- 41. Kaiser Family Foundation . Dental care health professional shortage areas (HPSAs). 2019. https://www.kff.org/other/state‐indicator/dental‐care‐health‐professional‐shortage‐areas‐hpsas/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D. Accessed June 17, 2020.

- 42. Doescher M, Keppel, GA . Dentist Supply, Dental Care Utilization, and Oral Health Among Rural and Urban U.S Residents. Seattle, WA: WWAMI Rural Health Research Center, University of Washington; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Patrick DL, Lee RS, Nucci M, Grembowski D, Jolles CZ, Milgrom P. Reducing oral health disparities: a focus on social and cultural determinants. BMC Oral Health. 2006;6(Suppl. 1):S4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pew Charitable Trusts . Dental therapy timeline. 2020. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research‐and‐analysis/data‐visualizations/2020/dental‐therapy‐timeline‐2020. Accessed June 17, 2020.

- 45. Community Catalyst . A sample dental therapy curriculum for community colleges. 2017. https://www.communitycatalyst.org/resources/publications/document/CommunityCatalyst_DT_Report.pdf. Accessed June 17, 2020.

- 46. Pew Charitable Trusts . Utilizing dental therapists in FQHCs. 2016. http://www.nnoha.org/download/utilizing‐dental‐therapists‐in‐fqhcs/. Accessed June 17, 2020.

- 47. National Network for Oral Health Access . Employing dental therapists in an FQHC: a NNOHA promising practice. 2016. http://www.nnoha.org/nnoha‐content/uploads/2018/05/Promising‐Practice‐West‐Side‐Community‐Health‐Services‐Junee‐2017_VN‐pt.pdf. Accessed June 17, 2020.

- 48. Oral health care: what foundations are supporting Health Aff. (Project Hope). 2019;38(5):872‐873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. American Association of Community Dental Programs. A call to action for community‐based oral health programs. 2018. https://www.aacdp.com/meetings/2018/index.html. Accessed June 22, 2020.

- 50. National Partnership for Dental Therapy . About the partnership. 2021; https://dentaltherapy.org/about/about‐the‐partnership. Accessed April 21, 2021.

- 51. Catlett A. Attitudes of dental hygienists towards independent practice and professional autonomy. J Dent hyg. 2016;90(4):249‐256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. American Dental Hygienists’ Association . Dental hygiene practice act overview: permitted functions and supervision levels by state. 2020. https://www.adha.org/resources‐docs/7511_Permitted_Services_Supervision_Levels_by_State.pdf. Accessed June 22, 2020.

- 53. American Dental Hygienists’ Association. State specific information on silver diamine fluoride. 2020. https://www.adha.org/resources‐docs/Silver_Diamine_Fluoride_State_by_State_Information.pdf. Accessed November 20, 2020.

- 54. American Dental Hygienists’ Association . Advocacy. 2020. https://www.adha.org/advocacy. Accessed June 22, 2020 .

- 55. American Dental Hygienists’ Association . Innovative workforce models. 2020. https://www.adha.org/workforce‐models‐adhp. Accessed June 22, 2020 .

- 56. Health Care for All . Who supports dental therapist legislation? 2018. https://www.hcfama.org/resources/who‐supports‐dental‐therapist‐legislation. Accessed June 22, 2020 .

- 57. American Dental Association . Community dental health coordinators provide solutions now. 2020. https://www.ada.org/~/media/ADA/Public%20Programs/Files/ADA_CDHC_Flyer_Infographic_Jan2020.pdf?la=en. Accessed November 20, 2020 .

- 58. National Network of Oral Health Access . Workforce and staffing. Operations Manual for Health Center Oral Health Programs. 2011. https://www.nnoha.org/nnoha‐content/uploads/2013/08/OpManualChapter5.pdf. Accessed June 22, 2020 .

- 59. Isong IA, Silk H, Rao SR, Perrin JM, Savageau JA, Donelan K. Provision of fluoride varnish to Medicaid‐enrolled children by physicians: the Massachusetts experience. Health Serv Res. 2011;46(6pt1):1843‐1862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. American State and Territorial Dental Directors . Silver diamine fluoride (SDF) fact sheet. 2017. https://www.astdd.org/www/docs/sdf‐fact‐sheet‐09‐07‐2017.pdf. Accessed June 22, 2020 .

- 61. Oral Health America . Oral health America. 2018. http://oralhealthamerica.org/. Accessed June 22, 2020 .

- 62. Children's Dental Health Project . CDHP's transition. 2019. https://www.cdhp.org/transition. Accessed June 22, 2020 .

- 63. Oberlander J. Long time coming: why health reform finally passed. Health Aff. (Project Hope). 2010;29(6):1112‐1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Skocpol T. The rise and resounding demise of the Clinton plan. Health Aff. (Project Hope). 1995;14(1):66‐85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. McDonough JE. Inside National Health Reform. Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Waldman HB. The response of the dental profession to change in the organization of health care—a commentary. Am J Public Health. 1973;63(1):17‐20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Ganski K. Discussion abounds on adding dental benefit in Medicare. 2018. https://www.ada.org/en/publications/ada‐news/2018‐archive/september/discussion‐abounds‐on‐medicare. Accessed June 22, 2020 .

- 68. American Dental Association . ADA letter on Medicare dental benefit. 2019. https://www.ada.org/~/media/ADA/Advocacy/Files/191619_ADALetteronMedicareDentalBenefit_WandM_sig.pdf?la=en. Accessed November 21, 2020 .

- 69. American Dental Association. ADA responds to news coverage of dental therapists. 2017. https://www.ada.org/en/press‐room/news‐releases/2017‐archives/february/ada‐responds‐to‐news‐coverage‐of‐dental‐therapists. Accessed July 7, 2020 .

- 70. Bersell HC. Access to oral health care: a national crisis and call for reform. J Dent Hyg. 2017;91(1):6‐14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Cladoosby B. Indian country leads national movement to knock down barriers to oral health equity. Am J Public Health Pract. 2017;107(Suppl.1):S81‐S84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Moeller J, Quinonez CR. Dentistry's social contract is at risk. J Am Dent Assoc. 2020;151(5):334‐339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Dorn AV, Cooney RE, Sabin ML. COVID‐19 exacerbating inequalities in the US. Lancet. 2020;395(10232):1243‐1244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. ADA Health Policy Institute. COVID‐19: economic impact on dental practices. 2020. https://surveys.ada.org/reports/RC/public/YWRhc3VydmV5cy01ZjBjNzZlNTQ1MDE1YzAwMGZlMjQ4ZjUtVVJfNWlJWDFFU01IdmNDUlVO. Accessed July 7, 2020 .

- 75. ADA Health Policy Institute . COVID‐19: economic impact on dental practices. 2020. Update. https://www.ada.org/~/media/ADA/Science%20and%20Research/HPI/Files/Practice‐Panel‐Wave‐24‐core‐report.pdf?la=en. Accessed April 20, 2021 .

- 76. American Dental Association . ADA: dentistry is essential health care. 2020. https://www.ada.org/en/publications/ada‐news/2020‐archive/october/ada‐dentistry‐is‐essential‐health‐care. Accessed November 21, 2020.

- 77. Krawczyk K. Washington Post analysis reveals coronavirus recession is “most unequal” in history. The Week. September 30, 2020. https://theweek.com/speedreads/940835/washington‐post‐analysis‐reveals‐coronavirus‐recession‐most‐unequal‐history. Accessed November 21, 2020.

- 78. Burgette JM, Weyant RJ, Ettinger AK, Miller E, Ray KN. What is the association between income loss during the COVID‐19 pandemic and children's dental care? J Am Dent Assoc. 2021;152(5):369‐376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Glassman P. Improving oral health using telehealth‐connected teams and the virtual dental home system of care: program and policy considerations. Boston, MA: DentaQuest Partnership for Oral Health Advancement; 2019. https://www.dentaquestpartnership.org/system/files/DQ_Whitepaper_Teledentistry%20%289.19%29.pdf. Accessed June 22, 2020 .

- 80. American Dental Association . New ADA toolkit offers guidance for providing COVID‐19 testing in dental practices. 2020. https://www.ada.org/en/publications/ada‐news/2020‐archive/october/new‐ada‐toolkit‐offers‐guidance‐for‐providing‐covid‐19‐testing‐in‐dental‐practices. Accessed April 21, 2021 .

- 81. American Dental Association. COVID‐19 vaccine regulations for dentists map. 2021; https://success.ada.org/en/practice‐management/patients/covid‐19‐vaccine‐regulations‐for‐dentists‐map. Accessed April 21, 2021.

- 82. Library of Congress. S.570 , Comprehensive Dental Reform Act of 2015. 2020. https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th‐congress/senate‐bill/570. Accessed November 21, 2020 .

- 83. Library of Congress. S.1129 , Medicare for All Act of 2019 . 2020. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th‐congress/senate‐bill/1129/text. Accessed November 21, 2020 .