Abstract

Toxin-specific enzyme immunoassays, cytotoxicity assays, and PCR were used to analyze 48 toxin A-negative, toxin B-positive Clostridium difficile isolates from various geographical sites around the world. All the isolates were negative by the TOX-A TEST and positive by the TOX A/B TEST. A deletion of approximately 1.7 kb was found at the 3′ end of the toxA gene for all the isolates, similar to the deletion in toxinotype VIII strains (e.g., C. difficile serotype F 1470). Additional PCR analysis indicated that the toxin B encoded by these isolates contains sequence variations downstream of the active site compared to the sequence of reference strain VPI 10463. This variation may extend the glucosylation spectrum to Ras proteins, as observed previously for closely related lethal toxin from Clostridium sordellii and toxin B from toxin A-negative, toxin B-positive strain F 1470. Toxin A-negative, toxin B-positive isolates have recently been associated with disease in humans, and they may be more common than was previously supposed.

Clostridium difficile is a major cause of nosocomial antibiotic-associated diarrhea (AAD) and colitis (22, 24). Symptoms of the disease range from mild diarrhea to fulminant pseudomembranous colitis (PMC). C. difficile is responsible for about 25% of cases of AAD diagnosed in the United States, although nearly all cases of the severe form of the disease are caused by C. difficile. The organism produces two toxins, termed A and B, that are responsible for the intestinal damage that occurs during infection. Strains of C. difficile that do not produce the toxins are not pathogenic (11).

Until recently, it was thought that all toxigenic strains associated with disease produced both toxins and that toxin A was required to produce the initial damage to the intestine (23). In 1991 and 1992 a strain that produced toxin B but no detectable toxin A was characterized (3, 21, 27). The strain, CCUG 8864, was shown to carry a large deletion in the toxA gene. Despite the absence of toxin A, CCUG 8864 causes disease in animal models. Furthermore, toxin B from this strain is weakly enterotoxic in rabbit intestinal loops and 10-fold more lethal than toxin B from strain VPI 10463. These findings suggested that strains that do not produce toxin A may still be capable of causing AAD. In 1993, serotype F strains were characterized as a second type of toxin A-negative, toxin B-positive (A−/B+) C. difficile (7). They were negative by toxin A-specific enzyme immunoassays (EIAs) but produced toxin B. Studies with serotype F strains (e.g., strain F 1470) indicated that they were not virulent in animal models. Serotype F strains are commonly isolated from asymptomatic children, further suggesting that they do not cause disease.

Rupnik et al. (26) recently characterized 10 toxinotypes (toxinotypes I to X) on the basis of deletions or additions within various regions of the toxin genes or other regions of the toxigenic element (also termed PaLoc) of C. difficile (14, 25). Of the 219 isolates characterized by Rupnik et al. (26), 47 contained variations in the toxin genes compared to the genes of reference strain VPI 10463. All the toxinotypes except toxinotype VIII and toxinotype X (of which CCUG 8864 is the only known strain) reacted in a toxin A-specific EIA. Of significance, 25 of the 47 defective strains were toxinotype VIII. A similar frequency of isolates with a deletion similar to that found in the toxA gene of toxinotype VIII was reported by Kato et al. (20). Others have also reported a relatively high frequency of C. difficile isolates with this characteristic deletion (4). Recently, A−/B+ isolates of C. difficile were implicated in an outbreak of AAD in Canada, and some patients developed PMC (1; M. Alfa, D. Lyerly, L. Neville, S. Moncrief, A. Al-Barrak, A. Kabani, B. Dyck, K. Olekson, and J. Embil, Abstr. 99th Annual Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology 1999, abstr. L-7, p. 440, 1999). Although further epidemiological studies are needed, it now appears that A−/B+ strains may be more common than was initially thought.

Toxic activity in a culture filtrate from toxinotype VIII strain F 1470 produces a cytopathic effect more closely resembling the effect of Clostridium sordellii lethal toxin (LT) (13; Alfa et al., Abstr. 99th Gen. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol. 1999). In addition, toxin B from F 1470 has a spectrum of glucosylation activity similar to that of LT, which, in addition to the Rho proteins, includes the Ras proteins as substrates (13, 16, 17, 18). In the case of LT, a region of the toxin just downstream of the active site has been associated with the ability to recognize Ras as a substrate (16). In our study, we show that isolates from around the world that are negative by toxin A-specific EIAs but that are positive for toxin B are genetically similar and resemble toxinotype VIII. In addition to a large deletion in the repeat region of the toxin A gene, PCR analysis revealed that the region that encodes the toxin B substrate recognition domain is similar among all toxinotype VIII isolates and may extend the spectrum of glucosylation to the Ras proteins.

C. difficile isolates were grown in dialysis sac cultures in brain heart infusion (BHI) medium for 72 h as described previously (22). Culture filtrates of C. difficile A−/B+ isolates (Table 1) were analyzed for immunoreactivity and the presence of cytotoxicity. Immunoreactivity was measured by an EIA specific for toxin A (TOX-A TEST; TechLab, Inc., Blacksburg, Va.) and a second EIA that detects toxin B in addition to toxin A (TOX A/B TEST; TechLab, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Titers were recorded as the reciprocal of the highest dilution with an A450 of 0.2 or greater. C. difficile strains of various phenotypes with respect to toxin production were included in the study as controls. Most previous biological and molecular characterization of the toxins has been done with reference strain VPI 10463, which produces large amounts of both toxins. VPI 11186 is a nontoxigenic strain and is completely missing the toxigenic element that encodes toxins A and B. F 1470 and CCUG 8864 represent the two known toxinotypes (VIII and X, respectively) that produce toxin B but that are not reactive in toxin A-specific EIAs. Culture filtrates from all A−/B+ isolates failed to react in the TOX-A TEST, whereas VPI 10463 had a titer of 105. CCUG 8864 also did not react in the TOX-A TEST. Culture filtrates from all the A−/B+ isolates reacted in the TOX A/B TEST, with titers ranging from 101 to 103. F 1470 had a titer of 102. CCUG 8864 and VPI 10463 each had a titer of 105. The culture filtrate of nontoxigenic strain VPI 11186 failed to react in either test.

TABLE 1.

C. difficile A−/B+ isolates used in the study

| Source | Location | Isolate(s) |

|---|---|---|

| M. Alfa and J. Embil | Canada | A 35533-9, A 35352-6, A 36060-9, A 35757-5, A 35089-1, A 36285-2, A 33479-8G, A 29090, A 30102, A 30103, A 30107, A 30112, A 35473 |

| J. Brazier | Wales, United Kingdom | R 7404, R 8721, R 9117, R 9624, R 10214, R 10627, R 10726, R 11092 |

| D. Craft | Chapel Hill, N.C. | TL 1321, TL 1334 |

| M. Delmee | Belgium | F 1470 (control), F 5768, F 6058, F 22484, IS F 37, IS F 73, F 43853, X 5036, X 20822, X 23682, X 23747, X 34084 |

| S. Johnson and S. Sambol | Chicago, Ill. | CF 2 |

| N. Kato | Japan | GAI 95600, GAI 95601, GAI 95602, GAI 95603, GAI 95604, GAI 95605, GAI 95606 |

| D. Turgeon | Seattle, Wash. | 101 C |

| TechLab | Various locations in the United States | TL 457, MLR, CRW, J 1165 W |

Culture filtrates from all 48 A−/B+ isolates had cytotoxic activity against CHO-K1 cells, with titers ranging from 103 to 105. F 1470 had a cytotoxicity titer of 105. VPI 10463 and CCUG 8864 had cytotoxicity titers of 105 and 106, respectively. The cytotoxic activities of A−/B+ isolates were neutralized by C. difficile VPI 10463 antisera as well as VPI 10463 toxin B-specific antibody.

The primers used to amplify regions of the toxin genes, along with their locations and the predicted sizes of the amplicons, are shown in Table 2. PCRs were performed with Ready to Go PCR Beads purchased from APBiotech (Piscataway, N.J.). Primers were from Gibco BRL Life Technology (Rockville, Md.). C. difficile isolates were grown on BHI plates overnight at 37°C in an anaerobic atmosphere by using oxygen-absorbent AnaeroGen (Oxoid, Ogdensburg, N.Y.) in a plastic anaerobic jar. For each reaction a single colony was placed into 100 μl of sterile deionized water. The tube was placed at 95°C for 5 min. Lysed cells were stored at −20°C until use. PCRs were performed in 25-μl volumes containing 10 μl of template DNA and each primer at a concentration of 1 μM. The annealing temperature varied according to the melting temperatures of the primers. PCRs were performed with denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, followed by 30 to 45 cycles with annealing for 1 min and elongation for 1 to 2 min at 72°C. All of the A−/B+ isolates and VPI 10463 were positive for CdB1, CdB4, CdB5, CdA1, and CdA2 reactions. Collectively, the results indicate that the entire toxB gene, as well as the region of the toxA gene upstream of the repeating units, is present in all of the A−/B+ clinical isolates. CCUG 8864 was negative for the CdA2 reaction.

TABLE 2.

Primers used for PCR analysis of C. difficile toxin genes

| PCR | Primers | Target gene | Location | Sequence | Amplicon size (kb) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CdB1 | B1F | toxB | 1–24 | ATGAGTTTAGTTATTAGAAAACAG | 1.79 |

| B1789R | 1769–1789 | CTAATTTTATCTCCTTGTAAC | |||

| CdB2 | TYBsrF | toxB | 927–948 | GATTTTTGGGAAATGACAAAG | 0.56 |

| TYBsrR | 1467–1487 | GCTTCTATCAAATGGATATTC | |||

| CdB3 | FBsrF | toxB | 931–948 | GTAGATTGGGAAGAGATG | 0.56 |

| FBsrR | 1475–1494 | CTCAGATGACAATATAGAAG | |||

| CdB4 | B4537F | toxB | 4537–4559 | TTGAAAGATGTCAAAGTTATAAC | 0.86 |

| B5394R | 5374–5394 | CAGGTACATCTTGTTTATCAC | |||

| CdB5 | B4162F | toxB | 4162–4183 | GAGATTAATTTTTCTGGTGAGG | 1.82 |

| B5984R | 5962–5984 | TCCTTTTTGCATAACTCCATCAG | |||

| CdA1 | A1F | toxA | 1–24 | ATGTCTTTAATATCTAAAGAAGAG | 1.77 |

| A1769R | 1749–1769 | TCATCTCCTTGTAACTGTATG | |||

| CdA2 | A4570F | toxA | 4570–4591 | TAACAGGAAAATACTATGTTG | 0.81 |

| A5382R | 5362–5382 | CATTATATATCCTAATGATAG | |||

| CdA3 | A5514F | toxA | 5514–5534 | TTCATTATTCTATTTTGATCC | 2.66 |

| AE5DR | 8158–8178 | TAATTTCTTAGTAGCACAGGA | |||

| CdA4 | A6007F | toxA | 6007–6027 | GCTATTGCCTTTAATGGTTAT | 1.18 |

| A7186R | 7166–7186 | CATTAATACTTGTATAACCAG |

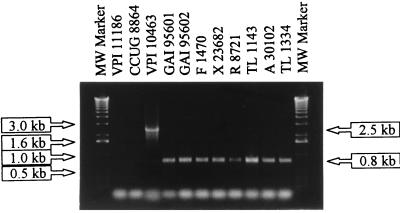

Primers for the CdA3 PCR flank the repeating units and were designed to analyze this region of the toxA gene. PCR CdA3 of VPI 10463 yielded an amplicon of the predicted size (approximately 2.5 kb) (Fig. 1). In contrast, all A−/B+ isolates yielded smaller identical products of 0.8 kb. The reaction products from representative isolates are shown in Fig. 1. These findings demonstrate that for all the isolates approximately 1.7 kb of DNA in the repeating units region has been deleted compared to the sequence of VPI 10463. To further verify that this region was missing from the variant isolates, primers designed to anneal to points that flank the two major PCG-4-binding epitopes were used for the CdA4 PCR (12). VPI 10463 but none of the A−/B+ isolates yielded the predicted PCR product of 1.2 kb (data not shown). CCUG 8864 did not react with either CdA3 or CdA4.

FIG. 1.

CdA3 PCR analysis of the repeating units of representative A−/B+ isolates GAI 95601, GAI 95602, F 1470, X 23682, R 8721, TL 1143, A 30102, and TL 1334. Results for control strains VPI 11186 (nontoxigenic), CCUG 8864 (toxinotype X, A−/B+ strain), and VPI 10463 (toxin A-positive and toxin B-positive reference strain) are also shown. Faint bands (primer dimers) at the bottom of the gel were present in all PCRs with these primers. MW marker, molecular size marker.

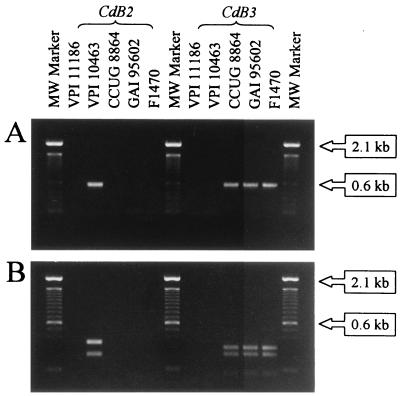

The primers for the CdB2 and CdB3 PCRs were designed to amplify a region of the toxB gene just downstream of the region that encodes the DXD (amino acids 286 to 288, VPI 10463 toxin B) active-site motif (5, 15). This region has been implicated in the recognition of Ras proteins by C. sordellii toxin LT that is closely related to toxin B (16). The sequence of strain F 1470 contains considerable divergence from VPI 10463 toxin B in this region (2, 9, 25). CdB2 primers were based on the sequence of VPI 10463, while CdB3 primers were based on the sequence of F 1470 (2, 9). Primers with sequences that matched the VPI 10463 sequence amplified a fragment of the predicted size for VPI 10463 but did not yield any product for any of the A−/B+ isolates (Fig. 2A). Conversely, the primers whose sequences were based on the F 1470 sequence amplified all the variant isolates (representative PCRs are shown in Fig. 2A), whereas no reaction was produced with VPI 10463. As predicted from the sequences of VPI 10463 and F 1470, digestion of PCR products with the restriction enzyme PsiI resulted in a pattern for the CdB2 PCR fragment from VPI 10463 different from that for CdB3 PCR fragments from A−/B+ isolates (Fig. 2B). Toxinotype X strain CCUG 8864 produced the same results as toxinotype VIII isolates with the CdB2 and CdB3 reactions and PsiI digestion.

FIG. 2.

(A) CdB2 and CdB3 PCRs of the toxin B gene downstream of the active-site motif. Representative A−/B+ isolates GAI 95602 and F 1470 are shown, along with control strains VPI 11186 (nontoxigenic), VPI 10463 (toxin A-positive, toxin B-positive reference strain), and CCUG 8864 (toxinotype X, A−/B+ strain). (B) CdB2 and CdB3 PCR products digested with PsiI. MW marker, molecular size marker.

In this study, we showed that a number of A−/B+ isolates from around the world were identical by PCR analysis with a series of primers designed to analyze various regions of both toxin genes. In particular, similar to the results of Rupnik et al. (26) and Kato et al. (19). a large region, was of toxin A repeating units from missing all A−/B+ isolates. This region encodes the epitopes for the monoclonal antibody used in toxin A-specific EIAs, suggesting a possible reason for the lack of reactivity (8, 12). Eichel-Streiber et al. (10), on the other hand, recently identified a nonsense mutation introduced at amino acid position 47 of the toxin A gene of strain F 1470 and two other A−/B+ strains that abrogated production of a functional toxin A. Furthermore, despite the large deletion, the repeating-unit region of F 1470 reacted with monoclonal antibody TTC8 (specific for the repetitive region of toxin A) when the region was expressed as a recombinant protein in Escherichia coli. This suggests that the lack of immunoreactivity in toxin A-specific EIAs is due to truncation by the nonsense mutation near the beginning of the toxin A gene.

The enzymatic domain at the 5′ end of the toxin B genes from A−/B+ strains F 1470 and CCUG 8864 has been sequenced (9, 25). Each of the strains is nearly identical to the other strain; however, their toxin B sequences vary considerably from the VPI 10463 toxin B sequence. The sequence variations are most striking in the region just downstream from the putative glucosylation active-site (DVD) motif (5). This region is associated with the extended spectrum of glucosylation by related toxin LT produced by C. sordellii (16). In addition to the Rho protein, LT glucosylates the Ras proteins (13, 17, 18). Toxins B from F 1470 and CCUG 8864 also glucosylate Ras, and it has been suggested that they represent hybrid toxins (6). In our study, we used primers based on the F 1470 toxB sequence to amplify this region in A−/B+ isolates. All the A−/B+ isolates yielded amplification products of similar sizes and gave similar patterns by restriction digestion with PsiI. VPI 10463, on the other hand, did not yield a PCR product with these primers. Conversely, primers whose sequences are based on a similar region of VPI 10463 toxB amplified VPI 10463 but none of the A−/B+ isolates. The sequence variations of the A−/B+ isolates suggest that they may glucosylate Ras proteins in addition to the Rho protein, as observed for F 1470. The effect of this variation on the pathogenesis of infections with A−/B+ isolates remains to be determined. Toxin B from CCUG 8864 is weakly enterotoxic in rabbit ileal loop assays. Studies on the enterotoxic activities of toxins B from toxinotype VIII strains have not been reported. Further studies on the biological properties of toxins B from toxinotype VIII strains, particularly their enterotoxic activities, are needed.

Acknowledgments

The C. difficile isolates used in this study were generously provided by Michelle Alfa and John Embil, Department of Microbiology, St. Boniface General Hospital, Winnipeg, Ontario, Canada; Jon Brazier, Anaerobe Reference Unit, Department of Medical Microbiology and Public Health Laboratory, University Hospital of Wales, Cardiff, United Kingdom; David Craft, Clinical Microbiology and Immunology Labs, University of North Carolina Hospital, Chapel Hill; Michelle Delmee, Microbiology Unit, Catholic University of Louvain, Brussels, Belgium; Haru Kato and Naoki Kato, Institute of Anaerobic Bacteriology, Gifu University School of Medicine, Gifu, Japan; Stuart Johnson and Susan Sambol, Department of Medicine, Veterans Affairs Chicago Health Care System, Lakeside Division, Northwest University Medical School, Chicago, Ill.; and David Tergin, Department of Laboratory Medicine, University of Washington.

REFERENCES

- 1.Al-Barrak A, Embil J, Dyck B, Olekson K, Alfa M, Kabani A. An outbreak of toxin A-negative, toxin B-positive Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea in a Canadian tertiary-care hospital. Can Communic Dis Rep. 1999;25:65–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barroso L A, Wang S Z, Phelps C J, Johnson J L, Wilkins T D. Nucleotide sequence of Clostridium difficile toxin B gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:4004. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.13.4004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borriello S P, Wren B W, Hyde S, Seddon S V, Sibbons P, Krishna M M, Tabaqchali S, Manek S, Price A B. Molecular, immunological, and biological characterization of a toxin A-negative, toxin B-positive strain of Clostridium difficile. Infect Immun. 1992;60:4192–4199. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.10.4192-4199.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brazier J S, Stubbs S L, Duerden B I. Prevalence of toxin A negative/toxin B positive Clostridium difficile strains. J Hosp Infect. 1999;42:248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Busch C, Hofmann F, Selzer J, Munro S, Jeckel D, Aktories K. A common motif of eukaryotic glycosyltransferases is essential for the enzyme activity of large clostridial toxins. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:19566–19572. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.31.19566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaves-Olarte E, Low P, Freer E, Norlin T, Weidmann M, von Eichel-Streiber C, Thelestam M. A novel cytotoxin from Clostridium difficile serotype F is a functional hybrid between two other large clostridial toxins. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:11046–11052. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.16.11046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Depetrie C, Delmee M, Avesani V, L'Haridon R, Roels A, Popoff M, Corthier G. Serogroup F strains of Clostridium difficile produce toxin B but not toxin A. J Med Microbiol. 1993;38:434–441. doi: 10.1099/00222615-38-6-434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dove C H, Wang S-Z, Price S B, Phelps C J, Lyerly D M, Wilkins T D, Johnson J L. Molecular characterization of the Clostridium difficile toxin A gene. Infect Immun. 1990;58:480–488. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.2.480-488.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eichel-Streiber C V, Meyer zu Heringdorf D, Habermann E, Sartingen S. Closing in on the toxic domain through analysis of a variant Clostridium difficile cytotoxin B. Mol Microbiol. 1995;17:313–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17020313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eichel-Streiber C V, Zec-Pirant I, Grabnar M, Rupnik M. A nonsense mutation abrogates production of a functional enterotoxin A in Clostridium difficile toxinotype VIII strains of serogroups F and X. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;178:163–168. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13773.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fluit A D C, Wolfhagen M J H M, Verdonk G P H T, Janse M, Torensma R, Verhoef J. Nontoxigenic strains of Clostridium difficile lack the genes for both toxin A and toxin B. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:2666–2667. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.11.2666-2667.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frey S, Wilkins T D. Localization of two epitopes recognized by monoclonal antibody PCG-4 on Clostridium difficile toxin A. Infect Immun. 1992;60:2488–2492. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.6.2488-2492.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Genth H, Hofmann F, Selzer J, Rex G, Aktories K, Just I. Difference in protein substrate specificity between hemorrhagic toxin and lethal toxin from Clostridium sordellii. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;229:370–374. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hammond G A, Johnson J L. The toxigenic element of Clostridium difficile strain 10463. Microb Pathog. 1995;19:203–213. doi: 10.1016/s0882-4010(95)90263-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hofmann F, Busch C, Prepens U, Just I, Aktories K. Localization of the glucosyltransferase activity of Clostridium difficile toxin B to the N-terminal part of the holotoxin. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:11074–11078. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.17.11074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hofmann F, Busch C, Aktories K. Chimeric clostridial cytotoxins: identification of the N-terminal region involved in protein substrate recognition. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1076–1081. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.3.1076-1081.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hofmann F, Rex G, Aktories K, Just I. The ras-related protein Ral is monoglucosylated by Clostridium sordellii lethal toxin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;227:77–81. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Just I, Selzer J, Hofmann F, Green G A, Aktories K. Inactivation of Ras by Clostridium sordellii lethal toxin-catalyzed glucosylation. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:10149–10153. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.17.10149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kato H, Kato N, Katow S, Maegawa T, Nakamura S, Lyerly D M. Deletions in the repeating sequences of the toxin A gene of toxin A-negative, toxin B-positive Clostridium difficile strains. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;175:197–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kato H, Kato N, Wantabe K, Iwai N, Nakamura H, Yamamoto T, Suzuki K, Kim S-M, Chong Y, Wasito E. Identification of toxin A-negative, toxin B-positive Clostridium difficile by PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2178–2182. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.8.2178-2182.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lyerly D M, Barroso L A, Wilkins T D, Depitre C, Corthier G. Characterization of a toxin A-negative, toxin B-positive strain of Clostridium difficile. Infect Immun. 1992;60:4633–4639. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.11.4633-4639.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lyerly D M, Krivan H C, Wilkins T D. Clostridium difficile: its disease and toxins. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;1:1–18. doi: 10.1128/cmr.1.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lyerly D M, Saum K E, MacDonald D K, Wilkins T D. Effects of Clostridium difficile toxins given intragastrically to animals. Infect Immun. 1985;47:349–352. doi: 10.1128/iai.47.2.349-352.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lyerly D M, Wilkins T D. Clostridium difficile. In: Blaser M J, Smith P D, Ravdin J I, Greenberg H B, Guerrant R L, editors. Infections of the gastrointestinal tract. New York, N.Y: Raven Press; 1995. pp. 867–891. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rupnik M, Braun V, Soehn F, Janc M, Hofstetter M, Laufenberg-Feldmann R, von Eichel-Streiber C. Characterization of polymorphisms in the toxin A and B genes of Clostridium difficile. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;148:197–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb10288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rupnik M, Avesani V, Janc M, von Eichel-Streiber C, Delmee M. A novel toxinotyping scheme and correlation of toxinotypes with serogroups of Clostridium difficile isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2240–2247. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.8.2240-2247.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Torres J F. Purification and characterization of toxin B from a strain of Clostridium difficile that does not produce toxin A. J Med Microbiol. 1991;34:40–44. doi: 10.1099/00222615-35-1-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]