Abstract

While social media are effective means of communicating with adverse customer emotions during a crisis, it remains unclear how tourism organisations can respond to pandemic crisis on social media to prevent negative aftermaths. Using a set-theoretical approach, we investigate how COVID-19 response strategies and linguistic cues of responses are intertwined to evoke positive emotions among consumers. This study entails a qualitative content analysis of tourism organisations' COVID-19 announcements and a social media analytics approach that captures consumers’ emotional reactions to these announcements via their Twitter replies. Our results extend some well-established findings in the tourism crisis literature by suggesting that combining innovative response strategy, argument quality, and assertive language can reinforce positive emotions during the COVID-19 crisis. Taking organisational characteristics into consideration, we suggest that young established hotels utilise innovative response strategies, whereas retrenchment response strategies for all types of restaurants should be avoided during the COVID-19 crisis.

Keywords: Coronavirus (COVID-19), Tourism crisis communication, Crisis response, Signalling theory, Consumer emotion, Social media analytics, Content analysis, fsQCA

1. Introduction

Coronavirus (COVID-19) has crippled many industries across the globe, especially the tourism industry. Most tourism destinations around the world have imposed restrictions on international travel, while 72% of the destinations put a complete halt to international tourism (UNWTO, 2020). Up to 50 million jobs were lost globally in 2020 as a result of lockdown in various regions (WTTC, 2020). These losses have affected all facets and actors of the tourism value chain, from destinations to service providers (e.g., airlines, hotels, and local restaurants) and from cultural tourism sites (museums) to tourism intermediaries (e.g., online travel agencies).

Following the launch of COVID-19 vaccines, consumer confidence has returned to its pre-COVID-19 level in the spring and summer of 2021 in many countries. As an example, UK consumers have been spending more on tourism and restaurants, with the number of “eating out” and “short holidays” increased by 50% and 24%, respectively, in comparison to the previous quarter (Q1 2021) (Deloitte, 2021). Most recently, nevertheless, responding to the new wave of restrictions on movement caused by the Omicron variant poses a new challenge to tourism organisations. To survive this pandemic and maintain a competitive position, hotels and restaurants must develop effective crisis communication strategies. Although prior research suggests that crisis communication through social media decreases negative customer reactions toward companies (Utz et al., 2013; Yuan et al., 2020), it remains unclear how tourism organisations can use social media to mitigate the negative outcomes of this global crisis.

Despite the existence of a wide range of literature regarding health-related crises using different theories, research designs and empirical settings (e.g. Lee & Chen, 2011; Novelli et al., 2018), the complexity of the COVID-19 crisis warrants revisiting crisis response strategies. Coronavirus pandemic has significantly changed service delivery and operation in tourism-related sectors. For instance, several hotel chains are revamping housekeeping operations and frontline service delivery, establishing new policies, and increasing customer trust to ensure that guests' health and safety are prioritised. In order to satisfy customer's expectations, a cohesive crisis response strategy, as well as an appreciation of linguistic cues, is essential. Furthermore, consumers expressing positive emotions can be used as a surrogate measure for managers to measure the success of crisis management (Argenti, 2020; Rocklage & Fazio, 2020; Wang et al., 2021). Consumers often express their emotions during a major crisis at their loved destination to demonstrate their support, closeness and to help its recovery (Filieri, Yen, & Yu, 2021).

In this study, consumer emotion is the primary outcome variable for two reasons. First, based on research on crisis management (Argenti, 2020; Wang et al., 2021), it is more likely that companies who are able to engage their customers on social media will survive during a crisis and remain competitive afterward (Yuan et al., 2020). Thus, it is crucial to understand consumer reaction to firms' crisis responses in times of crisis. Second, marketing literature suggests that consumers naturally express emotion when describing experiences with products, which is an integral part of the consumption experience (Filieri, 2016). Third, the situational crisis communication theory proposed by Coombs (2007) suggests that using effective response strategies can help alleviate the threat to the reputation of an organisation. Research on service failure and recovery on social media suggests that how a company responds (i.e. conversational human tone of voice) is particularly important to influence the perception of social media observers (Javornik et al., 2020), and it enhances consumers’ engagement and a more positive post-crisis perception (Yang et al., 2010).

In light of the significance of this topic and the gaps in research, we formulate the following research questions:

What are the most effective response strategies featured in social media posts to evoke positive consumers’ emotion during a major public health crisis?

And, do some linguistic cues in response strategies induce more positive emotions? If so, what are these combinations?

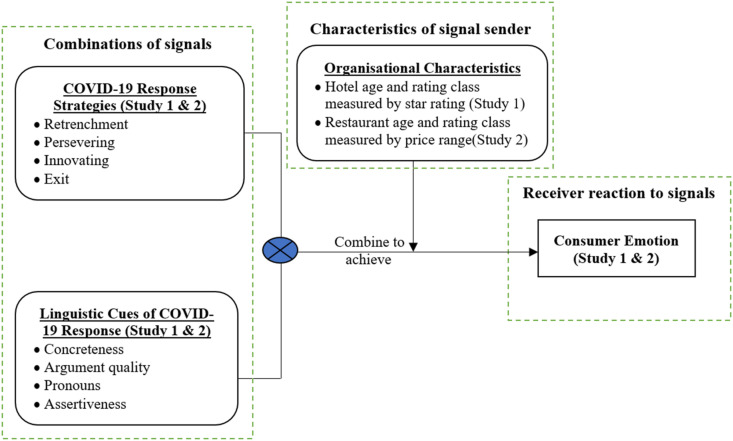

To answer these questions, underpinned by the complexity view of signalling theory, we aim to explain how linguistic cues and response strategies are combined to evoke positive consumer emotion regarding firms’ responses to the COVID-19 crisis. As per the signalling theory (Connelly et al., 2011), COVID-19 response strategies and linguistic cues are considered as the signal itself which affects the emotional reactions of its receivers. We propose a configurational model with a set of elements, including the COVID-19 response strategies of retrenchment, persevering, innovating, and exit (Wenzel et al., 2020) and linguistic cues (i.e. concreteness, argument quality, pronouns and assertiveness) that affect the manner in which individuals process COVID-19 responses. Furthermore, to better understand COVID-19 responses under different organisational characteristics such as star rating and firm age, we also consider the organisational characteristic as a contextual variable. This aims to provide tourism organisations with guidelines on crisis responses that best suit their unique organisational characteristics.

2. Theoretical background

2.1. Signalling theory - configurational effects among signals

Signalling theory posits that signals are observable attributes that can be used by individuals and organisations to communicate (Spence, 1973). Firms often use signals to provide information about the properties of products and services that are generally difficult to evaluate because of information asymmetries (Spence, 2002). Signalling theory defines signaller and receiver as two parties engaged in a signalling process that aims to reduce their information asymmetries (Connelly et al., 2011). Information asymmetry can be reduced by signals in different ways, depending on their signalling environments. Signalling theory provides the grounds to explain the various types of existing signals and the situations in which they are used (Filieri, Raguseo, & Vitari, 2021; Spence, 2002). This theory has been frequently used to study relationship recovery (Kharouf et al., 2020) organisational communication to customers (Wang et al., 2021), and to assess product quality signals in eWOM research (Filieri, Raguseo, & Vitari, 2021). In our study, signalling theory is applied to explain how tourism organisations (as signallers) utilise COVID-19 responses (as signals) posted on social media during the global pandemic crisis (as a signalling environment) to communicate with a wide range of consumers (as receivers). A COVID-19 response is regarded as a method for communicating the management's response to the crisis, such as explaining the causes of the crisis or providing efficient measures to ease consumer anxiety. When formulated properly, these responses can reduce negative feelings among customers following the public health crisis (Sigala, 2020).

Signalling theory research has evolved from focusing on a given signal to paying more attention to complex formulations and variations of the signal (Connelly et al., 2011). There has been little attention paid to the interaction of multiple signals in marketing literature. For instance, earlier work (e.g., Kirmani & Rao, 2000) conjectures that consumers are more likely to perceive a firm's signals as credible when it combines two distinct kinds of signals rather than bearing either of them separately. By empirically examining whether consumer's behaviour is influenced by the credibility and reliability of the combination of various types of signals, Basuroy et al. (2006) and Cox and Kaimann (2015) confirm Kirmani & Rao's conjecture. Basuroy et al. (2006) find that sales are positively affected by the interaction effect of signals (e.g., advertising expenditures and sequels). Likewise, multiple signals are taken into account by Cox and Kaimann (2015), showing that product reviews and a variety of quality signals (e.g., sequels, re-releases and mature age ratings) positively influence sales of video games. Recently, Wu and Reuer (2021) further argue that the interaction of signals determines the effectiveness of signals in facilitating desired outcomes.

The interaction of multiple signals can be also explained by configuration theory. A configuration refers to “a multidimensional constellation of the strategic and organisational characteristics of a business” (Vorhies & Morgan, 2003, p. 101). Configuration theory holds that businesses achieve their strategic goals and superior performance through the multiple, interdependent, mutually reinforcing configurations of organisational characteristics and business strategies (Meyer et al., 1993; Vorhies & Morgan, 2003). By extending prior studies examining the interaction effect of signals and configuration theory to our study's context, we explore how tourism organisations manage a portfolio of signals (i.e. a variety of strategies and linguistic cues of COVID-19 responses) and the interplay between different types of signals. More specifically, we develop our research model (see Fig. 1 ) by considering the organisational characteristics of tourism organisations in formulating crisis responses and the ways in which combinations of crisis response strategies and linguistic cues of responses may elicit positive emotions among consumers during the COVID-19 crisis.

Fig. 1.

Research model.

2.2. Crisis response strategy

A crisis response strategy is crucial for improving a firm's reputation and retaining customers (Coombs, 2007). Various strategies have been proposed in the crisis management literature to prevent, manage, and mitigate the negative effects of crises for firms. For example, research on service failures, such as product recalls and corporate reputation, provides insights into how firms can improve reputations and achieve positive consumer reactions (Hsu & Lawrence, 2016; Kharouf et al., 2020). Among the typology of crisis response strategies (e.g., Coombs, 2007; denial, diminishment, rebuilding, and bolstering), we selected Wenzel et al. (2020)'s four COVID-19 response strategies including retrenchment, perseverance, innovation, and exit, as they are specifically focused on responding to COVID-19, which is the perfect match for our research context.

Retrenchment strategies refer to a firm's “reductions in costs, assets, products, product lines, and overhead” in response to a crisis (Pearce & Robbins, 1994, p. 614). Companies use retrenchment strategies primarily to reduce costs through layoffs, product withdrawals, and asset reductions (Ndofor et al., 2013). This strategic response enables firms to focus on existing functions by reducing complexity and increasing transparency of behaviour (Benner & Zenger, 2016). Wenzel et al. (2020) contend that retrenchment strategies can be effective in companies facing crises as narrowing down costs can facilitate strategic renewal.

Persevering strategies refer to sustaining current activities in response to a crisis (Wenzel et al., 2020). When the status quo is maintained, a firm's ability to respond to crisis-related change in circumstances can be stabilised, thereby reducing the negative impact of crisis on the firm (Stieglitz et al., 2016). Prior research has indicated that customers' reactions to firms are greatly influenced by the persevering strategy adopted by firms. For example, in the economic crisis, Chakrabarti (2015) observed that firms with perseverance suffered fewer performance disruptions and were less likely to fail. The COVID-19 pandemic has prompted many tourism organisations to demonstrate their safe and comfortable ambiences, such as social distancing and timely customer services, as persevering responses to the pandemic. A survey conducted by Do et al. (2021) found that 25% tourism organisations had adopted a persevering strategy in response to COVID-19 and asserted this strategy enabled them to continue to build trust with customers while at the same time driving higher performance.

Innovating strategies refer to the “realisation of strategic renewal in response to crisis” (Wenzel et al., 2020, p. 11). Such responses suggest that firms are considering making use of the crisis to open up unthinkable or unfeasible business opportunities (Roy et al., 2018). As a result of the pandemic, firms are exploring new avenues for collaboration with customers, digitalising core competencies, shifting business models, and adding integrated resources to their customer databases (Seetharaman, 2020).

Exit strategies refer to the discontinuation of business activities, such as a temporary closure in the times of crisis (Wenzel et al., 2020). A crisis can cause unexpected devastation and challenges such as disrupted financial balance and untenable business models (Dahles & Susilowati, 2015; Seetharaman, 2020). Businesses that cease operations are able to retain some resources and build a better recovery after the crisis (Carnahan, 2017; Ren et al., 2019). Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, it is inevitable that many firms will close physical stores or discontinue normal services as directed by the government (Song et al., 2021). Besides reducing close contacts, this approach could also prevent the spread of the COVID-19 virus.

2.3. Linguistic cues

The way people process messages is influenced by linguistic cues, and the mode in which this processing occurs ultimately contributes to a change of attitude (Semin et al., 2005). To maximise the persuasive effect of the message, linguistic cues play an important role along with strategies that determine the content of a message (Pogacar et al., 2018). When transmitting a signal, the choice of linguistic cues can influence the receiver's perceptions and emotions. During a crisis, firms’ use of linguistic cues may affect how consumers perceive their announcements and their attitudes (Claeys & Cauberghe, 2014).

We conceptualise linguistic cues that frame response strategies in four dimensions: concreteness (Semin et al., 2005), argument quality (Briñol et al., 2012; Hoeken et al., 2020), pronouns (Sela et al., 2012) and assertiveness (Zemack-Rugar et al., 2017), which are based on a variety of literature in the fields of consumer behaviour, communication, and psychology. These four dimensions represent the dynamics of language use in sending different signals, and can be used to explicate the links between linguistic cues as signals being sent and customers’ emotions as reactions to the received signal.

Concreteness. The linguistic cue can be elaborated through the relative prominence of abstract versus concrete language in a message, by differentiating four levels of adjectives, state verbs, interpretive-action verbs and descriptive-action verbs, with a range from the most abstract to the most concrete (Semin et al., 2005). According to the linguistic category model proposed by Semin et al. (2005), interpretive-action verbs, state verbs and adjectives constitute the most abstract terms, while descriptive-action verbs are used to form the most concrete terms. The alternative context availability theory suggests that concrete words are easier to process and better support memory context than abstract words (Lydon et al., 2008). In times of crisis, the concreteness of language used in news and public announcements can affect consumer emotions (Borden & Zhang, 2019).

Argument quality. Argument quality refers to the degree to which a given argument persuades the audience that a given position is true. Conceptually it indicates the extent to which a persuasion process is conducted, and the motivation of the masses to scrutinise the claim (Briñol et al., 2012). The argument quality can be categorised into two types: strong arguments and weak arguments. Strong arguments are defined as “arguments evoking predominantly favourable thoughts when reflected upon”, whereas weak arguments “evoke mainly unfavourable thoughts” (Hoeken et al., 2020). Studies have demonstrated that the argument quality is shown to be an important linguistic device in determining whether a conclusion will be accepted and the persuasive power of information (Bhattacherjee & Sanford, 2006). Research on social media marketing communication suggests that the quality of arguments in marketing communication can affect customer attitudes toward brands (Chu & Kamal, 2008). Similarly, Chang et al. (2015) find that strong arguments tend to elicit favourable consumer responses, whereas weak arguments tend to generate negative consumer responses.

Pronouns. The manner in which pronouns are used affects the nature and quality of relationships between firms and their customers (Sela et al., 2012). First-person plural pronouns (e.g., “we” and “our”) indicate a closeness and community-based identity (Simmons et al., 2005), whereas first-person singular pronouns (e.g., “I") suggest an individuated identity and self-focus (Pennebaker et al., 2003). Specifically, closeness-implying pronouns can indicate a close relationship and shared identity and thus enhance persuasion, whereas second person and third-person pronouns (e.g., you and the brand) may emphasise consumer andbrand as separate entities (Sela et al., 2012).

Assertiveness. An assertive appeal is a type of linguistic device used for expressing a point of view clearly and directly, as in marketing communication (Kronrod et al., 2012a; Zemack-Rugar et al., 2017). Assertive language directs consumers and creates pressure for them to enact specific behaviours (Zemack-Rugar et al., 2017).

2.4. Organisational characteristics

Depending on nature of the business, size and geographic location, the duration and magnitude of the COVID-19 crisis impact may differ. When developing responses to the crisis, organisational characteristics should be considered as contextual variables, in order to understand how to formulate COVID-19 responses in a way that elicits positive consumer emotions under different organisational circumstances.

Firm age reflects brand image and influences firm performance (Li et al., 2020). Falk and Hagsten (2018) point out that young establishments may suffer from inexperience during a crisis, but they learn fast. This provides them with an opportunity to integrate into business practices and solutions. The COVID-19 pandemic has affected the working conditions and service operations of tourism workers, as well as the landscape of tourism. A significant amount of additional workload has been placed on the customer service departments of hotels and catering companies. The additional burden will be particularly detrimental to those that are relatively new and have little experience in dealing with the crisis.

Rating classification. The situational crisis communication theory proposed by Coombs (2007) suggests that customer perceptions of an organisation's crisis response are shaped by its reputational capital. This implies an organisation with a high prior reputation (e.g., five-star hotels or luxury restaurants) will have a favourable post-crisis reputation (Coombs, 2007). It is therefore important to consider different classes of restaurants and hotels since consumer expectations and perceptions of service quality differ between economy and luxury restaurants and hotels (Kim et al., 2019).

3. Method

3.1. Research setting and data

The purpose of this study is to evaluate the synergistic effects of crisis response strategies and linguistic cues on consumers' positive emotional states. The outcome variable in the study is consumers' sentiment scores, which represent their positive or negative emotions, in response to tourism organisations’ COVID-19 announcements posted on social media. The configurational elements, as independent variables, include eight categorical variables reflecting four types of response strategies and four types of linguistic cues in framing the COVID-19 responses. We test the configurational effects of these elements to understand their impacts on consumer emotions through using the fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA) approach.

We examine both the hotel (Study 1) and restaurant (Study 2) sectors in the UK, to leverage such configurational effects on the consumers’ emotional reactions. In Study 1, we firstly identified a list of UK hotels by adopting three criteria: 1) the company has more than 250 employees (i.e. non SMEs); 2) the hotel has an official Twitter account; and 3) hotels have posted at least one COVID-19 related tweets on their official account in the pandemic duration. After employing the selection criteria, a total number of 49 UK hotels were included in the research dataset. The data were collected with a coverage from March 1, 2020 (2 weeks before the official lockdown started on 16th March) to 31st July (before the ease of lock down and the Eat Out to Help Out scheme placed from 3rd to 31st August). A total number of 262 COVID-19 announcements for the UK hotels and 2953 consumer comments associated with these announcements were collected. We also provide an example below to show what information we have extracted from Twitter in this study (see Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

Example of extracting COVID-19 responses (tweets) and corresponding consumer comments (replies).

The purpose of Study 2 is to complement the results of Study 1 by further including the restaurant sector. In Study 2, we followed the same line of thought, identified a list of UK restaurants from the FAME database, and followed the three criteria as listed in Study 1 in company selection i.e. non-SMEs, with official Twitter accounts, and with COVID-19 tweets on their Twitter accounts. With a coverage from March 1, 2020 to July 31, 2020, a number of 47 companies were included, and their 211 associated Twitter announcements together with 12,252 consumer comments were collected.

3.2. Data analysis

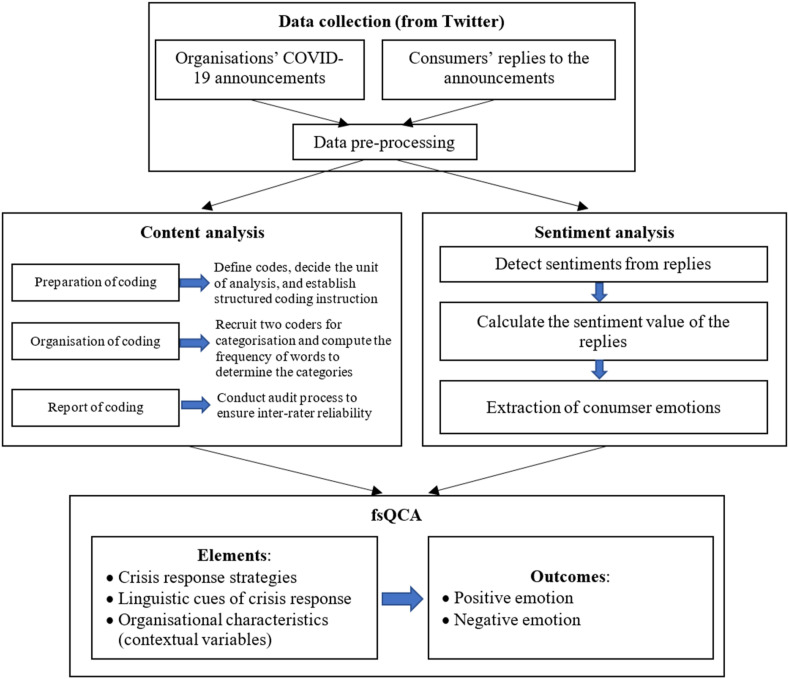

Fig. 3 demonstrates our data analysis procedures and explains how we integrate content analysis, sentiment analysis, and fsQCA in the analysis. The independent variables were measured through a three-step coding processes of content analysis on the tweets, and the outcome variable was measured using sentiment mining method to calculate the sentiment value of consumers’ replies.

Fig. 3.

Proposed framework integrating content analysis, sentiment analysis, and fsQCA.

3.2.1. Measurements

Crisis response strategy. Strategies in responding to crisis can be categorised into retrenchment, persevering, innovating and exit (Wenzel et al., 2020). We identify and categorise the strategies from the COVID-19 announcement through a rigours content analysis. Content analysis is considered as an appropriate approach to analyse documents or announcements with clear structures and flows, such as gaining insights from companies’ social media contents (Thomaz et al., 2017). Following the guidelines in the literature (Elo & Kyngäs, 2008), we use a three-step coding practice of preparing, organising and reporting to measure the four categories of response strategy.

The coding started with deciding the unit of analysis, the level of analysis and the purpose of evaluation (Elo & Kyngäs, 2008). We selected themes as the unit of analysis, looking primarily for the explanation or expression of a concept embodied in the tweet related to COVID-19 posted by tourism organisations. The level of analysis in this study is the restaurants and hotels that post their announcements on Twitter. The purpose of this coding process was to evaluate the different types of response strategy for each announcement.

We then established a structured coding instruction which guided and trained coders until they reached a specific level of reliability. Following suggestions from Krippendorff (2018), the coding instruction contains an outline, examples of the coding procedures, a general standard for data sheets administration and usage, and the definitions and examples of different types of response strategies (Krippendorff, 2018). Some confusions regarding classification were clarified and addressed by offering detailed descriptions and examples (see Appendix 1).

In the second step, we recruited two coders with substantial research experience to categorise the firms' responses to COVID-19 into relevant strategy category by using the dictionary of words established in the first step. We then computed the frequency proportion of words belonging to each strategy category divided by the total words of responses by using Kim and Kumar’s (2018) classification approach. An Excel table was provided to the coders to manage the responses extracted from Twitter.

In the final step, we conducted an audit process in order to improve the accuracy of classification (Krippendorff, 2018). Specifically, the two coders read the responses to COVID-19, computed and coded them by following the same coding process. The results of the two coders were compared. Initially, the two coders agreed on 89.5% of the classifications, which exceeded the recommended rate of 0.70 (Miles & Huberman, 1994). Further assessment was performed on particular responses where agreement could not be reached between the two coders. After discussions and debates, all the response classifications were agreed upon, and inter-rater reliability was ensured.

Linguistic cues of crisis response. Linguistic cues of crisis response can be categorised into concreteness, argument quality, pronouns and assertiveness. We used a similar three-step coding approach, as presented for response strategy, to categorise each announcement into abstration/concreteness (0 as low abstraction/high concreteness; 1 as high abstraction/low concreteness), argument quality (1 as strong argument provided; 0 as weak argument provided), pronouns (1 as community identity; 0 as individuated identity), and assertiveness (1 as assertive language used; 0 as non-assertive language used).

Concreteness. Abstraction and concreteness of language can be distinguished by four categories of interpersonal terms: descriptive-action verbs (DAV), interpretive-action verbs (IAV), state verbs (SV), and adjectives (AD). We examined how abstract versus concrete language evolved in COVID-19 announcements using a Linguistic Abstraction Index (LAI) (Semin et al., 2005; the equation is shown below). We first identified linguistic categories automatically by using IBM's Natural Language Processing. Two coders used the Classification Criteria for the Verb Classes (Semin & Fiedler, 1988) to distinguish DAV and IAV, and further used the Stative Verbs List1 to identify state verbs from other verb types. The index ranges from 1 to 4. Low concreteness (i.e. high abstraction) is defined as an index score above 2, while high concreteness (i.e. low abstraction) is defined as an index score below but including 2.

Where n1 = the number of DAV; n2 = the number of IAV; n3 = the number of SV; n4 = the number of AD.

Argument quality. To assess the quality of argument, we first learned from previous studies that have manipulated argument quality in their experiments (e.g., Raju et al., 2009). We then analysed argument quality using three criteria based on Toulmin's Model of Argument: evidence grounds, authority, and probability (Hoeken et al., 2020; Toulmin et al., 1984). An argument's ground refers to specific facts or evidence supporting a claim (Toulmin et al., 1984). Arguments that meet this criterion provide desirable outcomes or attributes that are supported by clear evidence. Argument authority is determined by how well a rational connection is made between argument and claim (Toulmin et al., 1984). This criterion helped us identify the weak arguments if the arguments failed to become relevant due to their lack of rational and logical connection to COVID-19 response strategies or because they had no effect on consumers' decisions (Chu & Kamal, 2008). Probability refers to the degree to which the argument's content can be accepted as true (Toulmin et al., 1984; Hoeken et al., 2020). If an argument meets the probability criterion, qualifiers and rebuttals are used to a greater extent, while words such as “may” and “probably” are used less (Boller et al., 1990). If a COVID-19 announcement has more high performance in three components (grounds, authority, probability), it is viewed as a strong argument.

Pronoun. In terms of pronoun, the two coders marked each COVID-19 announcement as community identity or individuated identity. The categorisations were based on the definitions and the following criterion: to identify community identity, we asked “does the announcement use plural pronouns or not?” and “does we, us, our, or ourselves present in the announcement?”

Assertiveness. Assertive language is determined when announcements 1) direct receivers to engage in specific behaviours (such as “Come and join us”); 2) use certain features in the communication to show confidence such as exclamatory mark and bold language; 3) use directional language (Zemack-Rugar et al., 2017). Based on the conceptual understanding, the two coders followed an audit process, as presented earlier in this section, to analyse the announcements. Specifically, the coders categorised each announcement on an individual basis to decide whether it belongs to assertive or non-assertive language usage. An Excel table was used to map the Tweet responses and their categorisation into assertiveness/non-assertiveness. After completion of individual coding, the results were compared with an agreement on 92% of the classifications, higher than the recommended rate of 0.70 (Miles & Huberman, 1994). Regarding the disagreed responses, further assessment and discussion were performed among the research team until reaching an acceptance among all the classifications.

Consumer emotion. Emotion is defined as “internal and subjective experience by an individual of a complex behaviour of physical and mental changes in reaction to some situation” (Batey, 2008, p. 25). A sentiment analysis of consumer comments on each COVID-19 announcement on Twitter was conducted, by using IBM Natural Language Processing, to identify consumer emotion based on how positive or negative their comment was. IBM Natural Language Processing could provide overall sentiment score on specific sentences (e.g., posts or replies on Twitter) ranging from 1 (extremely positive) to −1 (extremely negative) with a score of 0 representing neutral (Carvalho et al., 2019). As suggested in the product recall crisis literature (Hsu & Lawrence, 2016), the most market reaction occurs within six days after the product recall announcement date. We thus chose a 6-day as the time length to collect customer emotion to examine the combined effects of response strategy and linguistic cue within this time length. In total, the dataset of Study 1 contains 2953 online user comments regarding 262 COVID-19 announcements within 6 days were collected.

Organisational characteristics. Hotel and restaurant age is measured by the difference between the year of observation and year of business opening (Madanoglu & Ozdemir, 2016). In addition to firm age, we selected hotel and restaurant characteristics as a contextual variable and classified them into economy and luxury. Hotel class is measured by star rating (i.e. luxury hotels: 4/5 star and economy hotel: 1/2/3 star) (Kim et al., 2019). Restaurant class is measured by price range that can be found on the restaurant listings on Google review. Restaurants classified in the “£” and “££” pricing categories were assigned as Economy restaurants, while restaurants featured in the “£££” and “££££” were assigned as Luxury restaurants.

In Table 1 , we summarise the variables used in the study and their calibrations for fsQCA analysis.

Table 1.

Variables and their coding for fsQCA.

| Variables | Definition for coding | Role in theoretical model | Fuzzy set calibrations |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full membership | Crossover | Nonmembership | |||

| Consumer Emotion | Internal and subjective experience by an individual of a complex behaviour of physical and mental changes in reaction to some situation | Outcome variable | Sentiment value above 0.3 | Sentiment value between −0.3 and 0.3 | Sentiment value below −0.3 |

| Retrenchment | A COVID-19 announcement indicating a reduction in products or services | Relates to organisational level of the COVID-19 response strategy | 1 | – | 0 |

| Persevering | Firms announce that they will maintain as usual during COVID-19 crisis. | 1 | – | 0 | |

| Innovating | During COVID-19 crisis times, a firm's creative ways of displaying its products/services, or its new social practices that come along with it. | 1 | – | 0 | |

| Exit | Closing down or temporary closing of a business due to COVID-19 crisis. | 1 | – | 0 | |

| Abstraction/Concreteness | COVID-19 announcements with emphasis on particular activity that in general do not have positive or negative semantic valence. | Relates to organisational level of the linguistic cues of response | 1 (LAI score above 2 i.e. high abstraction/low concreteness) | – | 0) (LAI score below but including 2 i.e. low abstraction/high concreteness) |

| Argument Quality | Strong argument refers to firms' COVID-19 announcements with premised or evidence-based reasoning, while weak argument refers to those with absence of reasoning. | 1 | – | 0 | |

| Pronouns | The use of Pronoun is distinguished from firms' COVID-19 announcements with the use of plural pronouns to the use of singular pronouns. | 1 | – | 0 | |

| Assertiveness | Assertive language refers to firms' COVID-19 announcements that are confidence, forceful, or bold. | 1 | – | 0 | |

| Hotel age | Time difference between the year the hotel was founded and the year of retrieval (i.e. 2021) | Contextual variable (Study 1) | Determined by median split Young: ≤25; Old: > 25 |

||

| Star rating | Hotels are rated from Star 1 to Star 5 | Economy: 1/2/3 star; luxury: 4/5 star | |||

| Restaurant age | Time difference between the year the hotel was founded and the year of retrieval (i.e. 2021) | Contextual variable (Study 2) | Determined by median split Young: ≤23; Old: > 23 |

||

| Price range | Price are rated from £ to £££££ | Economy: £ and ££; luxury: £££ and ££££ | |||

3.2.2. fsQCA analysis

In model testing of complex phenomena (e.g., complexity of COVID-19 response), the fsQCA represents a powerful tool (Pappas, 2021). Based on Boolean algebra, this analytical approach uses an asymmetric method of thinking rather than a symmetric method (Park et al., 2020). FsQCA overcomes many of the drawbacks of conventional research, such as non-multicollinearity issues and normality issues arising from data. FsQCA uses a combination of indicators as causal recipes to predict the score of the desired outcome. Unlike the regression-based methods, fsQCA enable researchers to explain the existence of heterogeneity by considering the views of contrarian cases in the model testing of complex social phenomena that were overlooked in regression-based methods.

FsQCA approach is particularly suitable for this study since it allows for exploration of how various strategies and response framings can work together to produce more positive emotions as fuzzy-set outcomes (Fiss, 2011). In this study, fsQCA can help answer 1) Which of the theoretically possible configurations of COVID-19 response strategy and linguistic cues can be found in our data, and which cannot, 2) Which configurations are the most or least frequent in the data, and how often do cases appear in those configurations, and 3) What COVID-19 response strategies, or combinations of response strategies and linguistic cues, should be adopted in order for positive emotion to occur.

We followed Fiss (2011)'s three stages in the fsQCA analysis. We firstly calibrated measurements using membership scores in the first stage. Since all causal conditions are categorical data, they are transformed into crisp datasets in this study. For response strategies, the presence of all strategy-related conditions (retrenchment, persevering, innovating, and exit) is assigned a membership score (“1″), whereas the absence of these conditions is assigned a non-membership score (“0″). For linguistic cues, related conditions are categorical data, and membership or non-membership does not imply the condition's existence or absence, but rather its affiliation to respective categories. Specifically, for abstract/concrete response framing (noted as “AbsCon”), abstract frame is calibrated as 1 indicating the data is aligned with the use of abstract language frame, while concrete frame is calibrated as 0 indicating the data is aligned with the use of concrete language frame. Similarly, for argument quality framing (noted as “AQ”), strong argument frame is calibrated as 1 while weak argument frame is calibrated as 0. For the use of Pronoun (noted as “Pronoun”), frame with community identity is calibrated as 1 while frame with individuated identity is calibrated as 0. For the use of assertive language (noted as “Assertive”), assertive language frame is calibrated as 1 while non-assertive language frame is calibrated as 0. The outcome measurement of consumer emotion is regarded as fuzzy dataset, since it shows a varying degree to which consumers' emotional change towards the crisis response. We used Pineiro-Chousa et al. (2016)'s recommendations to assign full membership score to sentiment values above 0.3, full non-membership score to sentiment values below −0.3, and the crossover point to sentiment values around 0 (between −0.3 and 0.3).

The second stage consisted of reducing truth table rows according to conditions of 1) minimum number of cases required for an outcome (i.e. frequency threshold) and 2) minimum consistency level that represents that outcome (i.e. consistency threshold) (Ragin, 2008). Fiss (2007) notes that configuration with at least one case is considered as empirically pertinent, and Ragin (2008) argues that frequency threshold set as 1 is appropriate in small-N settings but should be set higher in large-N settings: for instance, Pappas et al. (2016) set 3 for a large dataset. Consistency indicates the degree to which cases under each combination of causal conditions are corresponded to the set theoretic relations in a solution (Rihoux & Ragin, 2008). As Ragin (2008) recommended, the minimum threshold as the lowest acceptable consistency for solutions is 0.75.

To address the problem of limited diversity in configurational analysis, the third stage involved reducing the truth table to a simplified combination through counterfactual analysis. (Ragin, 2008). In this study, both parsimonious and intermediated solutions are generated, and robustness analyses for the configurational results are conducted as detailed in the results sections.

4. Results of study 1 – the hotel sector

4.1. Configurations in the hotel sector

We firstly conducted a necessary condition test for the causal factors of response strategies and linguistic cues. A condition with its consistency that is above the typically used threshold (i.e. 0.75), is considered as a necessary condition (Ragin, 2008). According to the consistency value, non-retrenchment (0.81), non-exit (0.80), strong arguments (0.88) and assertive language usage in framing (0.83) qualify as necessary conditions. Therefore, these conditions are empirically valid and necessary for positive customer emotions in the hotel sector. In Appendix 2 we provide detailed results of the necessary condition tests.

Configurational solutions are presented in Table 2 in order to explicate multiple causal elements that lead to a high score of consumers’ positive emotions. We adopt the notation system established by Ragin and Fiss (2008) to express the configurations graphically, which allows to interpret the configuration structures, examine the simultaneous and systemically combination of elements, and explain the particular roles that each element plays in resulting positive consumer emotion (Park et al., 2017). Four configurations of response strategies and linguistic cues that consistently generate consumer positive emotions are depicted in the table, with each column representing a configuration of the eight elements. These configurations are also mapped into an ecology of configurations (Park et al., 2017) by using consistency, raw coverage and unique coverage. An explanation of detailed intermediate and parsimonious solutions is provided in Appendix 3.

Table 2.

Configurations sufficient for achieving positive emotion in the hotel sector.

| Solutions |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Configuration | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Strategy | ||||

| Retrenchment | ||||

| Persevering | ||||

| Innovating | ||||

| Exit | ||||

| Language | ||||

| AbsCon | ||||

| AQ | ||||

| Pronoun | ||||

| Assertive | ||||

| Consistency | 0.931 | 0.917 | 0.958 | 0.940 |

| Raw coverage | 0.215 | 0.248 | 0.296 | 0.151 |

| Unique coverage | 0.215 | 0.074 | 0.122 | 0.151 |

| Overall solution consistency | 0.923 | |||

| Overall solution coverage | 0.736 | |||

*Black circles indicate the presence of a condition, and circles with “X” indicate its absence. Large circles indicate core conditions; small ones, peripheral conditions. Blank spaces indicate “don’t care”.

S1 and S4 consist of innovating strategy, strong argument quality and assertive language cues as core elements, together with abstract language usage and pronoun of community identity as a peripheral element, respectively. However, innovating strategy is shown as absence in S2 and S3; these two solutions emphasise on strong argument quality (as a core) and pronoun of community identity (as a peripheral). The change of core conditions potentially implies that all strategies, apart from innovating, could reduce consumer's positive emotions. The absence of response strategy can be addressed via different pathways that emphasise the significance of linguistic cues.

S2 and S3 present pathways without innovating strategy, but instead, adopting persevering or null strategies as substitutive factors with similar structural configuration of linguistic cues. They both suggest the use of strong argument quality as a core condition, together with pronoun of social identity as a peripheral condition. This indicates that either adopting the strategy of retaining firms' status quo and their usual performance, or the strategy of not performing new actions, in combination with logically structured language that expresses the firms' confidence in their decisions is a potential pathway in gaining consumers’ understanding and positive emotions.

We further followed Douglas et al.’s (2020) approach to conduct analysis for negative emotions (i.e. ∼positive emotions or the absence of positive emotions). Pathways are found that lead to consumers' negative emotions and results are shown in Appendix 4. As demonstrated from the results, all solutions include abstract and ∼assertive language leading to negative emotions among consumers, which is consistent with results in Table 2.

The robustness of the fsQCA results was checked using three approaches including consistency threshold adjustment (Juntunen et al., 2019), sensitivity analysis for the crossover point (Park et al., 2020) and alternative measures (Lewellyn & Muller-Kahle, 2021). A detailed report of the results is presented in Appendix 5. The three analyses confirmed the robustness of the results.

4.2. Theoretical configurational propositions for particular hotel conditions

This study further develops an understanding of consumer emotion toward COVID-19 responses by using the contextual variables. To differentiate hotels, two contextual variables are selected: firm age and star rating. Via fsQCA analysis, we examine how all the causing elements combine together under the particular hotel conditions (i.e. old and economic hotels, young and economic hotels, old and luxury hotels, young and luxury hotels). We map configurations by using the Boolean expression (Ragin & Fiss, 2008) to explicate combinations between strategies and linguistic cues that lead to a high score of consumers’ positive emotions, as shown in Table 3 .

Table 3.

Solutions for achieving positive emotion in the hotel sector when considering contextual variables.

| Hotel Characteristics (Measured by star rating) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Economy (n = 25) | Luxury (n = 35) | ||

| Hotel Age | Old (n = 29) |

Solution 1: ∼Retrenchment*Innovating*∼Exit*AbsCon*AQ*∼Pronoun*Assertive Solution 2: Innovating*∼Exit*∼AbsCon*AQ*Pronoun*Assertive |

Solution 1: ∼Retrenchment*Persevering*∼Exit*∼AbsCon*AQ*Pronoun*Assertive Solution 2: ∼Retrenchment*∼Persevering*AQ*Pronoun*Assertive Solution 3: Innovating*∼Exit*∼AbsCon*AQ*Pronoun*Assertive |

| Young (n = 31) |

Solution 1: ∼Retrenchment*Innovating*∼Exit*AbsCon*AQ*∼Pronoun*Assertive Solution 2: ∼Retrenchment*Persevering*∼Exit*∼AbsCon*AQ*Pronoun Solution 3: Innovating*∼Exit*∼AbsCon*AQ*Pronoun*Assertive Solution 4: ∼Retrenchment*∼Innovating*∼AbsCon*AQ*Pronoun*Assertive |

Solution 1: ∼Retrenchment*Innovating*∼Exit*AbsCon*AQ*∼Pronoun*Assertive Solution 2: ∼Retrenchment*Persevering*∼Exit*∼AbsCon*AQ*Pronoun Solution 3: Innovating*∼Exit*AQ*Pronoun*Assertive Solution 4: ∼Retrenchment*∼AbsCon*AQ*Pronoun*Assertive |

|

Based on an analysis of the patterns of structures and constellations among old, young, luxury, and economic hotels, we propose an overarching proposition that applies to all types of hotels and emphasises the importance of argument quality as a type of linguistic cue in a crisis response. Across all four firm types, argument quality plays a key role in generating positive emotions, and different strategies can be employed according to the type of organisation. For instance, strong argument quality combined with either a non-retrenchment or innovating strategy may suffice for old firms, whilst strong argument quality coupled with an innovative strategy is effective for young companies. This is consistent with marketing and communication literature regarding the impact of argument quality on consumers (Bhattacherjee & Sanford, 2006; Chang et al., 2015). When presented with a message, strong arguments indicate higher persuasive power embedded in the message and can impact higher perceived usefulness and positive emotions toward the message and the brand.

Furthermore, the configurational approach implies that use of assertive language and strong argument quality when announcing strategies can generate more positive consumer reactions. During COVID-19, the hotel sector is one of those that is experiencing the most uncertainty and restrictions. Clear communication of the company's adopted strategy, backed by assertive and persuasive arguments, can help demonstrate the firm's proactive approach and ad hoc solutions during a crisis (Wong et al., 2021), which is crucial to improving consumer confidence and positive emotion towards the firm. Following this line of thought and based on the empirical results, we propose:

Proposition 1

For all hotels, regardless of the response strategy employed during a public health crisis, argument quality and assertiveness are sufficient to achieve more positive consumer emotions.

Our study shows that young hotels are often more likely to innovate if they do not exit the market (i.e. temporarily close). Young established hotels have a distinct disadvantage over older hotels that have already established routines and processes. New establishments may lack experience; however, they are more likely to learn quickly, which means they have a greater chance of incorporating novel practices and solutions (Falk & Hagsten, 2018). Therefore, innovative approaches in responding to the crisis demonstrate the young hotels’ ability to adapt their learning process and respond rapidly to various challenging situations. Therefore, we suggest:

Proposition 2

An innovative response strategy should be emphasised by young establishments in order to respond to public health crises more effectively.

5. Results of study 2 – the restaurant sector

5.1. Configurations in the restaurant sector

A necessary condition analysis is firstly conducted, with detailed results shown in Appendix 2. Non-retrenchment (0.86), innovating (0.77), non-exit (0.84), non-abstract information (0.72), strong argument quality (0.86), community-based identity use of pronoun (0.78), and assertive language in framing (0.91) are qualified for necessary conditions (above consistency threshold of 0.75).

The configuration results are presented in Table 4 . There are four configurations to achieve consumer positive emotions in the restaurant sector. The structure of the first two configurations is similar to that of S1 in the hotel sector. For S1 and S2, they both rely on an innovating crisis response strategy with avoidance of retrenchment and exit, and with a combination of strong argument and assertive language use. This demonstrates that during the pandemic, when firms decide neither retrench business nor exit the market, announcing an innovating strategy, together with strong argument and assertive language to emphasise the creative activities, can be useful in obtaining positive emotions among customers. Furthermore, S1 and S2 have a clear trade-off, with the use of abstract/concrete language and identity-based pronoun substituting for each other. Moreover, regardless of the response strategy employed during a public health crisis, S3 and S4 embrace the usage of high argument quality, community-based identity, and assertiveness (as a core condition). This indicates that these three conditions are more significant to explain response strategies during the pandemic.

Table 4.

Configurations for achieving positive emotion in the restaurant sector.

| Solutions |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Configuration | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Strategy | ||||

| Retrenchment | ||||

| Persevering | ||||

| Innovating | ||||

| Exit | ||||

| Language | ||||

| AbsCon | ||||

| AQ | ||||

| Pronoun | ||||

| Assertive | ||||

| Consistency | 0.943 | 0.917 | 0.980 | 0.971 |

| Raw coverage | 0.403 | 0.107 | 0.238 | 0.320 |

| Unique coverage | 0.223 | 0.107 | 0.058 | 0.141 |

| Overall solution consistency | 0.948 | |||

| Overall solution coverage | 0.709 | |||

*Black circles indicate the presence of a condition, and circles with “X” indicate its absence. Large circles indicate core conditions; small ones, peripheral conditions. Blank spaces indicate “don’t care”.

We also run the analysis for negative emotions (i.e. ∼ positive emotions or the absence of positive emotions) for the restaurant sector as shown in Appendix 4. It is notable that in S1 and S2 in Appendix 4, ∼ innovating strategy and ∼ argument quality (i.e. weak argument) are important elements to lead to negative emotions. In comparison with the S1 and S2 in Table 4–a combination between innovating strategy and strong argument quality contributing to positive consumers' emotions – results between the positive and negative emotion analyses are consistent. Furthermore, as Appendix 4 illustrates, ∼assertive language is a condition in resulting negative emotions, and reaffirms that respondance using assertive language are more likely to receive positive consumers’ emotions.

Similar to Study 1, we performed three robustness tests to confirm the robustness of configuration results, with results shown in Appendix 5. The results from both Study 1 (the hotel sector) and Study 2 (the restaurant sector) demonstrate that innovating strategy is essential in resulting positive consumer reactions. The two studies also reveal the synergistic effects of innovating strategy, strong argument quality and assertive emotion in achieving positive consumer reactions.

5.2. Theoretical configurational propositions for particular restaurant conditions

We have divided restaurant cases into four groups based on two contextual factors (firm age and price range): Old and Economy, Old and Luxury, Young and Economy, and Young and Luxury. Four truth table analyses are conducted with results presented in Table 5 .

Table 5.

Solutions for achieving positive emotion in the restaurant sector when considering contextual variables.

| Restaurant Characteristics (measured by price range) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Economy (n = 29) | Luxury (n = 7) | ||

| Restaurant Age | Old (n = 19) |

Solution 1: ∼Retrenchment*∼Persevering*AbsCon*AQ*Pronoun*Assertive Solution 2: ∼Retrenchment*Innovating*∼Exit*∼AbsCon*AQ*Pronoun*Assertive Solution 3: ∼Retrenchment*Persevering*Innovating*∼Exit*AbsCon*AQ*∼Pronoun*Assertive |

Solution 1: ∼Retrenchment*Innovating*∼Exit*∼AbsCon*∼Pronoun*Assertive Solution 2: ∼Retrenchment*Innovating*∼Exit*∼AbsCon*AQ*Pronoun Solution 3: ∼Retrenchment*Innovating*∼AbsCon*AQ*Pronoun*Assertive Solution 4: ∼Retrenchment*Persevering*Innovating*∼Exit*AbsCon *Pronoun*Assertive Solution 5: ∼Retrenchment*Persevering*∼Exit*∼AbsCon*AQ*Pronoun*Assertive |

| Young (n = 17) |

Solution 1: ∼Exit*∼AbsCon*AQ*Pronoun*Assertive Solution 2: ∼Retrenchment*Innovating*∼AbsCon*Pronoun*Assertive |

Solution 1: ∼Retrenchment*Innovating*∼AbsCon*AQ*Pronoun*Assertive Solution 2: Persevering*∼Exit*AbsCon*AQ*Pronoun*Assertive Solution 3: *∼Retrenchment*Persevering*Innovating*∼Exit*AbsCon*∼Pronoun*Assertive |

|

Two propositions are proposed to achieve positive consumer emotions across four types of organisations in the restaurant sector. First, an innovative response strategy appears to be an enabling condition for positive emotions, along with strong argument quality and assertiveness in linguistic cues. An innovative strategy seeks to engage in a new strategic renewal (Wenzel et al., 2020). In spite of the continuing uncertainty and complexity associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, there are also opportunities for restaurants to incorporate creative business strategies and activities, such as in-home recipes and a variety of delivery channels, to better adapt to the situation. It is evident from studies on crisis management that innovative strategies such as adopting new technologies can positively influence consumers’ emotions. (e.g., Crick & Crick, 2020).

Along with innovative response strategies, we have found that strong arguments and assertive language serve as conditions for reinforcing the impact of responses on consumer positive emotions. Nevertheless, in some consumer behaviour studies, assertive language appears to negatively influence consumer compliance (e.g. Zemack-Rugar et al., 2017). A possible explanation is that the effect of assertive language on consumer behaviour might be context dependent (Kronrod et al., 2012a). For example, Kronrod et al. (2012b) demonstrated that assertiveness appeal can be effective in resulting in customer satisfaction when involving hedonistic products or activities. During the pandemic, an announcement of innovative strategies in an assertive manner and with a clear focus by restaurants can be helpful to enhancing consumer confidence. Therefore, we propose:

Proposition 3

For all restaurants, using linguistic cues of argument quality and assertiveness to enhance an innovating response strategy can assist them in achieving positive consumer emotions during a public health crisis.

Secondly, the analysis reveals that retrenchment strategies, such as reduction of costs and narrowing of service channels, should be excluded from the configurational solutions. Despite the fact that literature suggests that during times of crisis, retrenchment strategies contribute to remain profitability (Wenzel et al., 2021), enable the company to rebound from recessions (Barker et al., 2001) and reduce work complexity (Benner & Zenger, 2016), downsizing and cost-saving initiatives can leave customers feeling uncertain (Habel & Klarmann, 2015; Homburg et al., 2012). Restaurants may reduce costs on business activities and menu choices, and limit serving lines to only allow take-away orders, but this can result in a decline in consumer satisfaction and an increase in anxiety towards the firm and the pandemic situation. Therefore, we suggest:

Proposition 4

A retrenchment response strategy should be avoided for all restaurants during a public health crisis.

6. General discussion

Using real-world data from the UK restaurant and hotel industries, this study empirically examines how response strategy, linguistic cues, and organisational characteristics interact to create positive emotional reactions. Our study is among the first to use the fsQCA method for offering new insights into the complicated formulation of crisis responses. Our results extend some well-established findings in the tourism crisis literature by suggesting that combining innovative response strategy, argument quality, and assertive language can reinforce positive emotions. In the following sections, we discuss the theoretical and practical implications.

6.1. Theoretical implications

This research contributes to the tourism crisis management in several ways. First, tourism organisations' crisis management initiatives involve readiness, response, and recovery (3Rs). The 3Rs are crucial in mitigating the negative consequences of the crisis for travel & tourism businesses, stakeholders and tourists’ well-being (Ritchie, 2008). Since it is likely that consumers will pay more attention to the actions tourism organisations take during a crisis, our study emphasises the importance of tourism organisations responding quickly in crisis situations. Thus, our results contribute to the understanding of how to craft crisis responses to achieve a positive consumer reaction.

Second, while conventional wisdom suggests that tourism crisis responses should define the crisis responsibly, explain its causes, provide appropriate warnings to tourists, and suggest how market uncertainty and consumer anxiety can be mitigated (Millar & Heath, 2003), we explain how this can be accomplished in a more nuanced way. For instance, our findings suggest that argument quality is sufficient for achieving more positive consumer emotions regardless which response strategy is adopted during a public health crisis. However, for young hotels, they should formulate responses in an innovating manner to facilitate consumers’ positive emotions when responding to a public health crisis on social media platforms.

Moreover, some solutions from fsQCA analysis suggest that response strategy merely plays a marginal role in achieving consumer positive emotion, especially for retrenchment and reserving strategies. For instance, our findings reveal that retrenchment response strategy should be avoided for all restaurants during a public health crisis. We suspect that this is due to COVID-19 information given from various sources (e.g., government authorities) are overwhelmed. Thus, providing tedious responses may lead to the perception of information overload or possibly create anxiety or stress for tourism consumers. As a result, we provide novel findings, compared to the findings of prior research (e.g., Novelli et al., 2018), suggesting that when formulating tourism crisis response, tourism practitioners should consider a shift in emphasis away from a response strategy per se towards focusing on linguistic cues and response framing. This is evident by a recent study undertaken by Wang et al. (2021) where it was found that consumer trustworthiness could significantly recover when firms frame their COVID-19 related tweets in an emotional way, regardless of what response strategy is used.

In addition, this study contributes to the signalling theory by exploring the configurational effects among signals and how they impact on signal receivers' emotions. In this regard, we confirm Kirmani and Rao’s (2000) conjecture of signalling theory by suggesting that consumers' positive emotions during the COVID-19 crisis may have resulted from a combination of various types of crisis responses. We also theorise how the signallers' characteristics influence the synergetic effectiveness of the signal on a specific signalling environment (i.e. social media environment). Considering the characteristics of signallers, we suggest specific combinations of signals to different types of signallers (such as young establishments and economic hotels) in order to formulate crisis responses. Thus, the configurational effect of signals advances our understanding of tourism crisis response as it not only investigates the direct impact of crisis response but also the conjunctural causation and the interaction effect of crisis response on consumer reactions.

6.2. Practical implications

Crisis management teams need to prepare to communicate in ways which ensure all consumers, and other stakeholders, fully understand the emerging situation. At the same time, further actions to return to normal operation start to take place at the recovery stage. Actions include minimising current damage and future risks to the organisation and its stakeholders, promulgating a well-structured recovery plan, implementing recovery strategies and monitoring their effectiveness on any functional aspect of the business. Outlining these actions with the appropriate response strategies will not only safeguard the health of customers and employees but also, help restore consumer confidence and reduce perceived risk. We suggest a crisis management team to develop the crisis communication by using bucket testing or scenario planning that allows them to better understand the effectiveness of potential crisis communication, and what will be happening and which actions to take next.

Derived from the fsQCA results, we summarise the managerial implication for hotels and restaurants and this guidance can be applied at the crisis recovery stage, shown in Table 6 .

Table 6.

A summary of managerial implications on COVID-19 responses for hotels and restaurants.

| Sectors | Managerial implications |

|---|---|

| Hotels |

|

| Restaurants |

|

7. Conclusion

Tourism practitioners have been rethinking the communication strategies for the post-COVID-19 period as adequate and relevant responses to customer concerns could stimulate their revisit intentions. In the global pandemic crisis context, this study provides actionable solutions to tourism organisations on how to formulate the announcements related to the pandemic crisis via social media platforms to elicit customers’ positive emotions. We further identify some promising research directions worthy of scholarly investigation.

First, tourism researchers are encouraged to further study what the effective communication methods (e.g., visual and audio communications) that could offer proper responses, in order to reduce tourism consumers' concerns and provide corrective and restorative guidance following a crisis. The exemplar research questions specific to this research direction are “How crisis response formulated in a visual or audio format can generate positive consumer reactions?”, “How can visualisation of crisis response ideally be implemented to benefit from consumer trust?” and “What are the visual or audio mechanisms in the marketing communication process that can induce tourism consumers’ revisit intention following a crisis event?”

Second, risk perception will vary towards different destinations (most versus less affected). Scholars could consider perception of risk to travel across most, and least, affected countries to disentangle the impact of crisis response on travellers' behavioural and emotional reactions. Furthermore, research could investigate other contextual variables for the crisis response-consumer reactions link, considering, for example, tourists' risk aversion, or other destination level factors, such as destination brand attachment, destination brand love and the like. The inclusion of these factors could improve understanding of the conditions that would mitigate, or heighten, travellers’ reactions toward crisis responses.

Third, responding rapidly to, and bouncing back from, such a large-scale crisis requires to involve tourism stakeholders such as online travel agents (OTAs). OTAs can speed up the recovery to help tourism organisations circulate crisis responses or marketing messages following a crisis. Thus, future research is encouraged to explore what the role of OTAs can play in response to global pandemic, and how tourism organisations cope with crisis with OTAs through coordination mechanisms.

Finally, the use of Twitter data alone may create limitations since Twitter may provide different insights from other social media platforms. Online reviews may not capture all corporate communication signals. Although some researchers have claimed that brand-related sentiment in user-generated content does not differ across social networking sites (Smith et al., 2012), future studies which investigate the effect of responses to public health crises on consumer sentiment across different social media platforms would be beneficial.

Authorship contributions

Shuyang Li (First author): Conceptualisation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, and Writing – original draft. Yichuan Wang (Second author & Corresponding author): Conceptualisation, Investigation, Validation, and Writing – original draft, and Supervision, Raffaele Filieri (third author): Writing- Reviewing and Editing, and Supervision. Yuzhen Zhu (fourth author): Formal analysis, Methodology, and Validation

Impact assessment

Many tourism practitioners are struggling to make appropriate responses to their consumers during COVID-19 outbreak. To address this challenge, we guide the different type of hotels and restaurants to develop the crisis communication in order to win consumer positive emotion through the appropriate response strategies and linguistic cues. This study is closely aligned with the latest UK Parliament's COVID-19 Area of Interests - communication strategy for public health messages. Specifically, the findings obtained from this study can contribute to the discussion of the key research question - “How do different approaches to communicating uncertainty affect people's likelihood to follow guidance?”. Extending from our findings, policy makers should consider the potential effect of linguistic cues when developing public health communication strategies shared in social media aimed at engaging citizens to follow measures and guidance.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Biographies

Dr. Shuyang Li is a Lecturer (Assistant Professor) in Information and Operations Management, and Programme Director for MSc Logistics and Supply Chain Management at the Sheffield University Management School, University of Sheffield. She received her PhD in Information Studies from the University of Sheffield. Her research interests include information systems, organisational digital transformation, impact of technologies and social media marketing. Her work has been published in British Journal of Management, Information Systems Frontiers, Technological Forecasting and Social Change, Industrail Marketing Management,Industrial Management and Data Systems, and others.

Dr. Yichuan Wang is an Associate Professor of Digital Marketing at the Sheffield University Management School, University of Sheffield, UK. He holds a PhD degree in Business & Information System from the Raymond J. Harbert College of Business, Auburn University, USA. His research focuses on examining the role of digital technologies and information systems in influencing business practices. His research has been published in the Tourism Management, Journal of Travel Research, Annals of Tourism Research, British Journal of Management, International Journal of Operations & Production Management, Information & Management, Industrial Marketing Management, and various IEEE Transactions. He sits in the editorial board of Journal of Business Research, Enterprise Information Systems, International Journal of Consumer Studies, and Computer & Electrical Engineering.

Dr. Raffaele Filieri is Professor of Digital Marketing in the Marketing Department at Audencia Business School, Nantes, France. His research interests include eWOM, social media marketing, online trust, online value co-creation, technology adoption and continuance intention, branding, and inter-firm knowledge management. His researches have appeared in Tourism Management, Annals of Tourism Research, Journal of Travel Research, Journal of Interactive Marketing, Journal of Business Research, Industrial Marketing Management, Psychology & Marketing; International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, International Journal of Hospitality Management, Information & Management, Transportation Research Part E; Information Technology & People; Computers in Human Behavior, Technological Forecasting & Social Change, International Journal of Information Management, Journal of Consumer Affairs, Expert System, Journal of Brand Management, Journal of Knowledge Management and many more.

Yuzhen Zhu is a PhD researcher in information systems field & organisation field. His PhD topic is focusing on the role of information communication technologies (ICTs) in the shaping of interorganisational knowledge exchange practices in the context of European Living Labs. Yuzhen's research interests relate to digital technologies for diverse contexts such as business, management, marketing, and (inter-)organisational collaborations.

Footnotes

No funding is received for this study.

A list of 56 stative verbs can be found at https://www.perfect-english-grammar.com/stative-verbs.html.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104485.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Argenti P.A. Communicating through the coronavirus crisis. Harvard Business Review. 2020 https://hbr.org/2020/03/communicating-through-the-coronavirus-crisis Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Barker V., Patterson P., Mueller G. Organizational causes and strategic consequences of the extent of top management team replacement during turnaround attempts. Journal of Management Studies. 2001;38(2):235–270. [Google Scholar]

- Basuroy S., Desai K.K., Talukdar D. An empirical investigation of signalling in the motion picture industry. Journal of Marketing Research. 2006;43(2):287–295. [Google Scholar]

- Batey M. Routledge; London: 2008. Brand meaning. [Google Scholar]

- Benner M.J., Zenger T. The lemons problem in markets for strategy. Strategy Science. 2016;1(2):71–89. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacherjee A., Sanford C. Influence processes for information technology acceptance: An elaboration likelihood model. MIS Quarterly. 2006;30(4):805–825. [Google Scholar]

- Boller G.W., Swasy J.L., Munch J.M. ACR North American Advances; 1990. Conceptualizing argument quality via argument structure. [Google Scholar]

- Borden J., Zhang X. Linguistic crisis prediction: An integration of the linguistic category model in crisis communication. Journal of Language and Social Psychology. 2019;38(5–6):650–679. [Google Scholar]

- Briñol P., McCaslin M.J., Petty R.E. Self-generated persuasion: Effects of the target and direction of arguments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2012;102(5):925–940. doi: 10.1037/a0027231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnahan S. Blocked but not tackled: Who founds new firms when rivals dissolve? Strategic Management Journal. 2017;38(11):2189–2212. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho A., Levitt A., Levitt S., Khaddam E., Benamati J. Off-the-shelf artificial intelligence technologies for sentiment and emotion analysis: A tutorial on using IBM Natural Language processing. Communications of the Association for Information Systems. 2019;44(1):43. [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabarti A. Organizational adaptation in an economic shock: The role of growth reconfiguration. Strategic Management Journal. 2015;36(11):1717–1738. [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y.T., Yu H., Lu H.P. Persuasive messages, popularity cohesion, and message diffusion in social media marketing. Journal of Business Research. 2015;68(4):777–782. [Google Scholar]

- Chu S.C., Kamal S. The effect of perceived blogger credibility and argument quality on message elaboration and brand attitudes: An exploratory study. Journal of Interactive Advertising. 2008;8(2):26–37. [Google Scholar]

- Claeys A.S., Cauberghe V. What makes crisis response strategies work? The impact of crisis involvement and message framing. Journal of Business Research. 2014;67(2):182–189. [Google Scholar]

- Connelly B.L., Certo S.T., Ireland R.D., Reutzel C.R. Signalling theory: A review and assessment. Journal of Management. 2011;37(1):39–67. [Google Scholar]

- Coombs W.T. Protecting organization reputations during a crisis: The development and application of situational crisis communication theory. Corporate Reputation Review. 2007;10(3):163–176. [Google Scholar]

- Cox J., Kaimann D. How do reviews from professional critics interact with other signals of product quality? Evidence from the video game industry. Journal of Consumer Behaviour. 2015;14(6):366–377. [Google Scholar]

- Crick J., Crick D. Coopetition and COVID-19: Collaborative business-to-business marketing strategies in a pandemic crisis. Industrial Marketing Management. 2020;88:206–213. [Google Scholar]

- Dahles H., Susilowati T.P. Business resilience in times of growth and crisis. Annals of Tourism Research. 2015;51:34–50. [Google Scholar]

- Do B., Nguyen N., D'Souza C., Bui H.D., Nguyen T.N.H. Strategic responses to COVID-19: The case of tour operators in Vietnam. Tourism and Hospitality Research. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- Elo S., Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. Journal Of Advanced Nursing. 2008;62:107–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk M., Hagsten E. Influence of local environment on exit of accommodation establishments. Tourism Management. 2018;68:401–411. [Google Scholar]

- Filieri R. What makes an online consumer review trustworthy? Annals of Tourism Research. 2016;58:46–64. [Google Scholar]

- Filieri R., Raguseo E., Vitari C. Extremely negative ratings and online consumer review helpfulness: The moderating role of product quality signals. Journal of Travel Research. 2021;60(4):699–717. [Google Scholar]

- Filieri R., Yen D.A., Yu Q. # ILoveLondon: An exploration of the declaration of love towards a destination on Instagram. Tourism Management. 2021;85:104291. [Google Scholar]

- Fiss P. Building better causal theories: A fuzzy set approach to typologies in organization research. Academy of Management Journal. 2011;54(2):393–420. [Google Scholar]

- Habel J., Klarmann M. Customer reactions to downsizing: When and how is satisfaction affected? Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science. 2015;43(6):768–789. [Google Scholar]

- Hoeken H., Hornikx J., Linders Y. The importance and use of normative criteria to manipulate argument quality. Journal of Advertising. 2020;49(2):195–201. [Google Scholar]

- Homburg C., Klarmann M., Staritz S. Customer uncertainty following downsizing: The effects of extent of downsizing and open communication. Journal of Marketing. 2012;76(3):112–129. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu L., Lawrence B. The role of social media and brand equity during a product recall crisis: A shareholder value perspective. International Journal Of Research In Marketing. 2016;33:59–77. [Google Scholar]

- Javornik A., Filieri R., Gumann R. “Don't forget that others are watching, too!” the effect of conversational human voice and reply length on observers' perceptions of complaint handling in social media. Journal of Interactive Marketing. 2020;50:100–119. [Google Scholar]

- Juntunen J.K., Halme M., Korsunova A., Rajala R. Strategies for integrating stakeholders into sustainability innovation: A configurational perspective. Journal of Product Innovation Management. 2019;36(3):331–355. [Google Scholar]

- Kharouf H., Lund D.J., Krallman A., Pullig C. A signalling theory approach to relationship recovery. European Journal of Marketing. 2020;54:2139–2170. [Google Scholar]

- Kim B., Kim S., King B., Heo C.Y. Luxurious or economical? An identification of tourists' preferred hotel attributes using best–worst scaling (BWS) Journal of Vacation Marketing. 2019;25(2):162–175. [Google Scholar]

- Kim K.H., Kumar V. The relative influence of economic and relational direct marketing communications on buying behavior in business-to-business markets. Journal of Marketing Research. 2018;55(1):48–68. [Google Scholar]

- Kirmani A., Rao A.R. No pain, no gain: A critical review of the literature on signalling unobservable product quality. Journal of Marketing. 2000;64(2):66–79. [Google Scholar]

- Kronrod A., Grinstein A., Wathieu L. Go green! Should environmental messages be so assertive? Journal of Marketing. 2012;76(1):95–102. [Google Scholar]