Abstract

Background

Most people with acne are at risk of developing acne scars, but the impact of these scars on patients' quality of life is poorly researched.

Objective

To assess the perspective of patients with acne scars and the impact of these scars on their emotional well-being and social functioning.

Methods

A 60-minute interview of 30 adults with acne scars informed and contextualized the development of a cross-sectional survey of 723 adults with atrophic acne scars.

Results

The main themes identified in the qualitative interviews included acceptability to self and others, social functioning, and emotional well-being. In the cross-sectional survey, 31.6%, 49.6%, and 18.8% of the participants had mild, moderate, and severe/very severe acne scarring. The survey revealed that 25.7% of the participants felt less attractive, 27.5% were embarrassed or self-conscious because of their scars, 8.3% reported being verbally and/or physically abused because of their scars on a regular basis, and 15.9% felt that they were unfairly dismissed from work. In addition, 37.5% of the participants believed that their scars affected people's perceptions about them, and 19.7% of the participants were very bothered about hiding their scars daily. Moreover, 35.5% of the participants avoided public appearances, and 43.2% felt that their scars had negatively impacted their relationships.

Limitations

The temporal evaluation of the impact was not estimated.

Conclusion

Even mild atrophic acne scarring can evoke substantial emotional, social, and functional concerns.

Key words: acne scarring, atrophic scars, mixed methods, population-based survey, quality of life

Abbreviation used: SEM, standard error of the mean

Capsule Summary.

-

•

Atrophic acne scars can evoke substantial concerns, including acceptability to self and others, and impact social functioning and emotional well-being.

-

•

As acne scars result from a lack of acne control in the past, evidence-based data on the negative psychological sequelae from acne scars should be used in the quest to prevent scarring from acne.

-

•

Acne scarring can evoke substantial concerns, including acceptability to self and others, and impact social functioning and emotional well-being.

-

•

Preventive measures aimed at reducing the development of acne scarring are integral to prevent the associated debilitating psychosocial effects from acne scars.

Introduction

Facial acne scarring has been estimated to affect clinically 55% of patients with acne.1 These sequelae can be persistent and can be lifelong.2 Many studies have attempted to describe the psychosocial effects of acne, but few have explored the effects of acne scarring.3, 4, 5, 6

A mixed-methods approach with an explanatory sequential design was used to investigate the potential psychological and functional impact of acne scarring independent of active acne; first, qualitative exploratory data were collected, and findings were used to develop a quantitative survey adapted to the sample under study. The survey was, in turn, administered to a sample of a population of adults with atrophic acne scars in the absence of active acne on their faces.

Here we present the key aspects of the experience, perception, and attitude of those living with atrophic acne scars highlighted during the qualitative interviews when tested in a large survey to quantify the impact of acne scars on psychosocial well-being. The qualitative data were also used to provide context to numerical values derived from the quantitative survey, enhancing the relevance of the findings.

Materials and methods

This mixed-method study integrated the data from qualitative interviews and a quantitative survey of a large sample of individuals with facial atrophic acne scars. Both interviews and questionnaire surveys were conducted and administered in the native language of each country (ie, United States, Canada, Brazil, France, Italy, and Germany) from 2019 to 2020. The mixed-method study was conducted sequentially, with the qualitative part run before the quantitative one to inform the quantitative questionnaire design with the qualitative findings. The research complied with General Data Protection Regulation, all international/local data protection legislation, and Insights Association/European Society for Opinion and Marketing Research/European Pharmaceutical Market Research Association/British Healthcare Business Intelligence Association. All subjects provided informed consent before participation. The study received a favorable opinion from the Kantar Health internal institutional review board/ethics committee. Study design, data collection, data management, and analyses were conducted by Kantar Health.

The eligible participants were aged 18 to 55 years, with mild to severe facial atrophic acne scars. The participants' acne was to be clear (no active lesions) or almost clear (eg, a few scattered open or closed comedones and very few acne papules) during the 2 years before the survey. The presence and severity of acne were self-reported based on the self-rated Global Assessment.1 To help self-assessment of acne severity, photo scales and/or text descriptions were provided as examples of severity. The self-assessment of the Clinical Acne-Related Scars questionnaire was used to rate the severity of facial atrophic acne scars.7 Photographs of the different types of postacne scars were shown to patients in the quantitative survey to help the recognition of atrophic scars.

Qualitative survey procedures

Data collection

Thirty participants with facial atrophic acne scars were recruited following a purposeful sampling strategy for a 60-minute telephone semistructured interview conducted by qualitative researchers as previously described.8

Data analysis and interpretation

Qualitative data were descriptively analyzed using audio records and a content-analysis grid. Data were organized by themes in a content analysis format. Analyses that aimed at identifying emerging themes related to the overall quality of life were based on the grounded theory method. Data were coded in terms of basic psychosocial processes, based on how participants acted in response to different contexts. The local qualitative analyst did the first level of analysis, based on a content-analysis template to ensure homogeneity of the summarized findings. At a global level analysis, the 2 independent coordinating qualitative researchers integrated the local analysis with a focus on identifying and describing country similarities and differences in responses. Validation of findings included a craftsman approach that involves continually checking, questioning, and theoretically interpreting findings. The voices of participants were emphasized through verbatim quotes reported with the unfiltered wording of the participants. The study was designed and conducted in accordance with the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research requirements (Supplementary Material 1, available via Mendeley at https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/74jmrrhg9d/1).9

Quantitative survey procedures

Data collection

A cross-sectional, quantitative survey of an online respondent panel was conducted across 723 participants as previously described.10 The survey was developed following insights from the qualitative study (ie, exploratory sequential design). Clinical experts established the face and content validity of the survey (JT and BD). In addition, the following validated health-related quality of life scales were included: the Dermatology Life Quality Index, the Facial Acne Scar Quality of Life, and the Dysmorphic Concern Questionnaire.7,11,12 Linguistic translation into each country's local language was conducted in accordance with the conventional methodology (backtranslation was performed using TransPerfect).

Data analysis and interpretation

A quota sampling method based on geographical location was used to ensure that the sample of respondents was representative of the acne populations in the study countries. Age, sex, and country weighting adjustment were applied (Supplementary Material 1, available via Mendeley at https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/74jmrrhg9d/1). The country was modeled as the primary sampling unit to account for the clustering of data at the country level. Continuous variables were analyzed using the Student t test or with analysis of variance and expressed as the mean and standard error of the mean (SEM). Categorical variables were analyzed using the chi-square independence test and were expressed as frequencies. All tests were 2-tailed, and a value of P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Sample demographics and clinical characteristics

In total, 30 participants (5 per study country) were recruited for the qualitative interviews; 21 (70%) participants were aged 25 to 45 years. The majority (18/30, 60%) of the participants were women. At the time of the interview, the last episode of active facial acne lesion was 2 to 5 years ago for 23 of 30 (76.7%) participants and >5 years ago for 7 (23.3%) participants. Twenty-two (73.3%) participants had previously received a prescribed treatment for acne.

Of the 723 subjects who participated in the quantitative survey, 92 (12.7%), 512 (71.8%), and 112 (15.5%) were aged 18 to 24, 25 to 45, and 46 to 55 years, respectively, and 373 (51.6%) were women (Supplementary Table Ib, available via Mendeley at https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/74jmrrhg9d/1). Overall, 70% of the participants had acne diagnosis at a mean age of 16 years (SEM, 0.39), and 88% of the participants received the prescribed treatment for acne. The mean duration of acne was 10 years (SEM, 0.32). Overall, 81.2% of the participants reported having had their past acne under control, either totally (19.5%) or partially (61.7%). In total, 50.2% of the participants were informed of the risk of developing scars from acne during prior medical consultations and 67% discussed scar prevention strategies with physicians.

The participants started to experience atrophic acne scars at a mean age of 19.1 years (SEM, 0.39) and had scarring for a mean of 15.7 years (SEM, 0.35); 31.6%, 49.6%, and 18.8% participants had mild, moderate, and severe/very severe scarring, respectively. Increased scar severity was associated with lack of acne control in the past (P = .003) and longer acne duration (on average 11.6 years [SEM, 0.46] for patients with severe/very severe scarring and 9.6 years [SEM, 0.35] for patients with mild/moderate scarring [P = .007]). In total, 66.6% of the participants with atrophic scars had a family history of acne scarring. Irrespective of the severity of scarring, 42.9% had consulted a physician regarding their scars. For those receiving treatment for scars, the time elapsed between scar onset and treatment was 2 years (SEM, 0.26).

Impact of acne scars on health-related quality of life

Appearance and acceptability to self and others

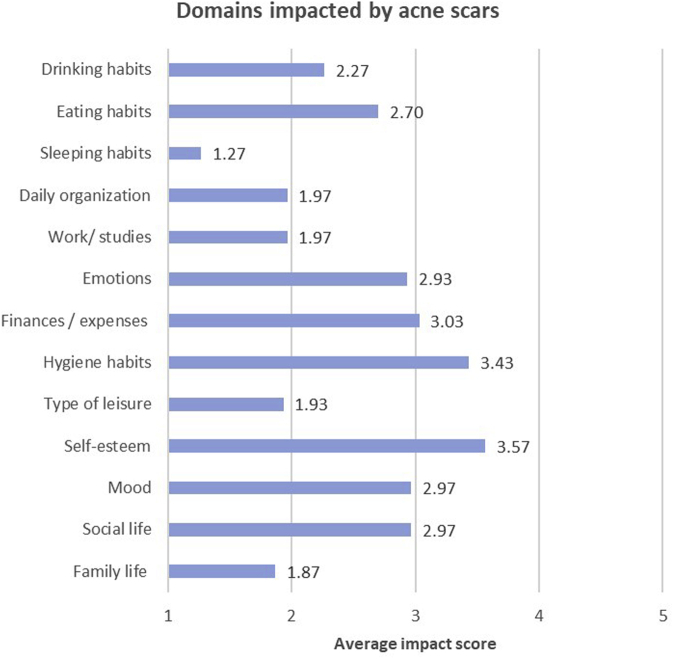

In the qualitative interviews, recurrent themes on the burden of atrophic acne scars were reduced self-esteem and self-consciousness, with self-esteem ranking the highest (Fig 1). The lexical fields of ugliness/beauty and themes such as the wish for the scars to disappear were commonly reported in the interviews.

Fig 1.

Domains affected by acne scars. Self-completion ranking exercise to score impact on a 5-point Likert scale where 1 indicates “no impact at all” and 5 indicates “extreme impact” before the qualitative interview (N = 30).

“It is not nice looking!” (A woman in France)

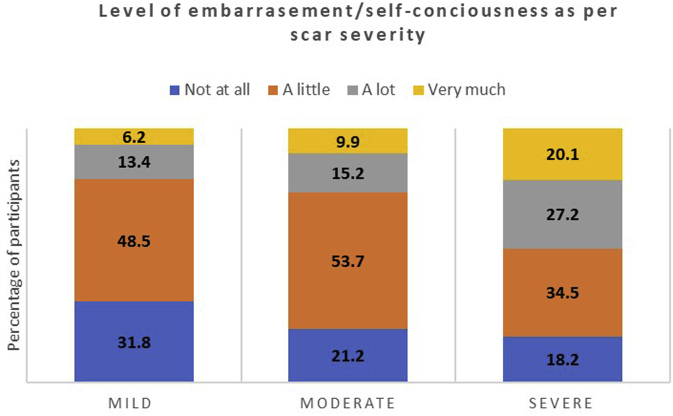

Many participants from the quantitative survey also reported being dissatisfied with the appearance of their atrophic acne scars; 51.8% felt unattractive because of their acne scars; 25.7% felt “extremely” or “much less” attractive than others. Both embarrassment/self-consciousness and level of bother related to the scar appearance increased with scar severity, and these feelings were still fairly common among participants with mild scarring (Fig 2). Embarrassment was also a recurring subtheme of the qualitative interviews: “But I'm not going to lie to you that to take a picture, depending on the light I'm embarrassed because I know they [acne scars] are very apparent.” (A woman in Brazil)

Fig 2.

Percentage of participants who felt embarrassed/self-conscious based on scar severity grade.

Some participants from the quantitative survey felt stigmatized by their scars; 32.9% reported being subject to people's negative comments due to their acne scars, 12.6% felt “a lot/very much” upset about them, and 8.3% reported to be verbally and/or physically abused because of their scars on a regular basis. More than 37.0% of the participants felt that scars affected people's perception of them. Stigmatization was also expressed by the qualitative survey participants: “The scars were for me the black dot on a white sheet. Everyone could see them and too many times the people just only see it, not all the rest.” (A woman in Italy)

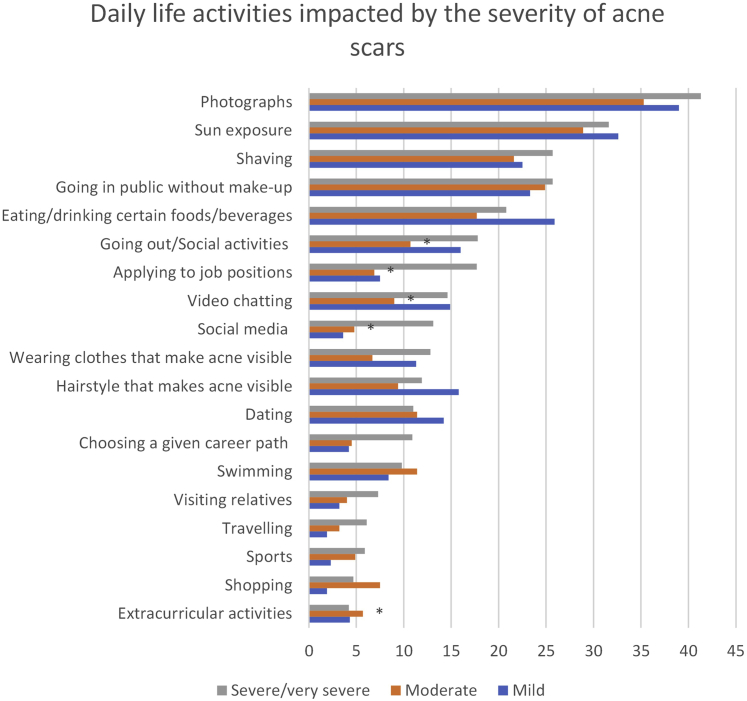

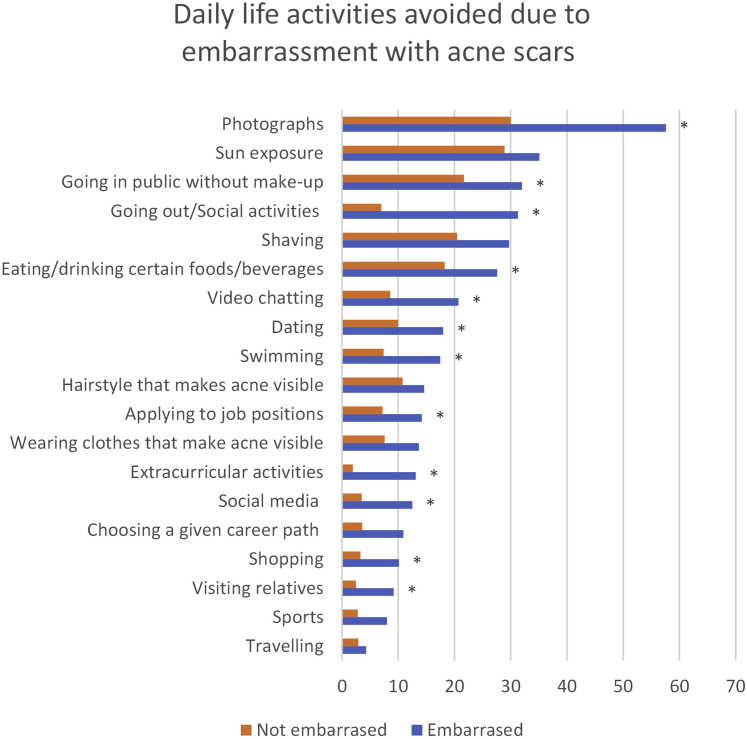

Considering atrophic acne scar appearance and the reactions of others, 19.7% from the quantitative survey felt “very” or “extremely” bothered and reported covering their scars with clothes, hairstyle, or makeup; 24.5% of the participants would not leave their homes without applying makeup (Fig 3). In both qualitative and quantitative studies, embarrassment was associated with behavioral change to camouflage the scars (Fig 4): “It's an issue leaving the house without makeup.” (A woman in Germany)

Fig 3.

Percentage of participants who avoided daily life activities because of their acne scars. ∗P<.05.

Fig 4.

Percentage of participants who avoided daily life activities due to embarrassment because of their acne scars. ∗P<.05.

Social functioning

Work life and leisure activities

Irrespective of the scar severity, 8.6% of the participants from the quantitative survey felt that their work life was “very much/extremely” affected, 15.9% felt that they have been unfairly dismissed from work or passed over for a job, and 6.6% reported frequent unfair treatment at work because of their scars.

Leisure activities such as sunbathing and swimming that exposed the scars were avoided by 30.6% and 10.2% of the participants, respectively (Fig 3). Overall, 35.5% of the participants stated that their scars prevented them from engaging in activities that they like to do. Similar reactions were expressed during qualitative interviews: “I wanted to do hot yoga as I could not put on anything to cover the scars and have to put my hair up so I cannot hide. I would be completely exposed.” (A woman in Canada)

Sociability and personal relationships

In the qualitative survey, participants scored the domain social life as 3 on a 5-point scale (where 5 means extremely impacted by scars) and expressed the negative impact of atrophic acne scars on their social lives using terms such as shame, insecurity, and discomfort. “It is always difficult for me to meet new people. I'm insecure. I continuously try to hide the scars wearing makeup.” (A woman in Italy)

Hygiene and eating habits were also impacted by scars and were scored 3 each.

The participants from the quantitative survey reported avoiding situations where they could be observed, such as going out in the public and participating in social activities (13.7%), social media (6.0%), and video chatting (11.9%) due to their acne scars. Overall, 43.2% of the participants felt that their scars had a negative impact on their relationships (Fig 3). “When he kissed me, he must see my scars, it must not be beautiful, I had no confidence in myself.” (A woman in France)

Daily life was also impacted, as participants reported adopting changes to limit exposure to risk factors for acne (Fig 3).

Emotional well-being

The appearance of scars, stigma from scars, and daily life restrictions experienced due to scars adversely affected the emotional well-being of the participants: It bothers me a lot and makes me sad.” (A woman in Brazil)

Irrespective of the scar severity, the participants in the quantitative survey felt “very much” or “extremely” sad (16.5%), annoyed (22.1%), and worried (24.9%) about the future development of their scars, as they realized that their scars may never completely disappear.

Over half (53.2%) of the participants in the quantitative survey thought that existing treatments/procedures to improve atrophic acne scars were problematic (expensive, long healing time, etc). “I made two or three laser therapeutic sessions in a medical/beauty salon. I was not so satisfied. I paid a lot, and I can't see an evident benefit” (A woman in Italy)

Overall, 36.2% reported having no control over their scars, and 28.4% felt that nothing could be done to improve the appearance of facial acne scars. “Nothing will really help the scars. It sucks if you have really bad scars. Let's do everything we can to treat the acne and prevent the scars.” (A woman in the USA)

Moreover, 75.8% indicated that even a minor improvement in scarring would be worthwhile.

The quantitative survey participants had a strong desire for scar prevention, and the majority (75.5%) reported any additional measures to their current acne management as valuable to prevent scarring: “Long term consequences are important. I wish I had learned about scars, how to prevent them, while the acne was occurring.” (A man in the USA)

“No advice given about scars. All doctors should tell you what's going on, explain it. I would try to prevent the scars, make sure I didn't have scars.” (A man in the USA)

Accordingly, in the quantitative survey, overall, 36.3% felt disappointed by their physicians' decisions regarding the care/management of their acne in the past, and 60.0% regretted their own decisions related to the past acne management; regret increased with acne scar severity (P = .108 and P = .0003 for the association between physician and subject regret, respectively, with scar severity).

“I really feel that the acne scars could be taken more into consideration by the dermatologist. I thought that I would be in good hands, but all I felt was alone and misunderstood.” (A woman in Germany)

Discussion

Over 25% of the participants with atrophic acne scars were highly embarrassed and self-conscious about their scarring. Consistent with the previous observations, even mild scarring was found to evoke substantial concerns.3 These results highlight the main areas of impact, including acceptability to self and others, social functioning, and emotional well-being. Over half of the participants indicated feeling less attractive than others, and over one-third reported their scars as highly bothersome. Stigmatization was also experienced as previously reported, and participants indicated that acne scars interfered with professional relationships and chances of employment.3 This observation is in line with research showing that those with acne scars are perceived differently by the society and that the presence of acne scars can negatively impact perceived attributes, skills, and prospects.13

Almost a quarter of the participants reported adopting coping behaviors such as hiding or covering their scars, which ultimately resulted in impaired social functioning; social dysfunction in relation to atrophic acne scars included concerns about social interactions with the opposite sex (12%) or public appearances (14%). Leisure activities were also negatively affected as a third of the participants avoided public appearances and refrained from engaging in activities they would otherwise have liked. Overall, dissatisfaction about the appearance of scars, stigmatization, and daily life restrictions were sources of worries, sadness, and/or frustration, which could explain, at least in part, the association between acne scarring and depression.13,14

In line with previous work, the risk of atrophic acne scarring increased with a lack of acne control in the past.2,7,15,16 Nevertheless, only 70% of the participants with acne scars had received a prior diagnosis of acne, 50% of the participants were never informed about the risk of scarring from acne, and 67% of those who were informed discussed prevention strategies with physicians. Given that half of the participants had concerns regarding the inconvenience of current therapies, prognosis, and management of the acne scars, most participants reported a strong desire for scar prevention and the majority reported any additional measures to their current acne management as valuable to prevent scarring.

The study used a combination of deductive and inductive methods for the initial item generation, and its content validity was assessed by 2 independent clinical experts. However, the construct validity and reliability of the survey were not assessed. Other potential limitations of this study are that the participants were required to willingly participate in the survey and complete it online and recruitment relied on self-reported scar severity, although as recently reported by others, the self-assessment may be seen as an advantage rather than a limitation.17

Conclusions

Atrophic acne scars exert a substantial negative impact on quality of life and functionality of affected individuals, and the psychological impact is potentially burdensome. Acne scar management remains challenging, and scars may remain an indelible and permanent feature after acne. Therefore, effective therapies aimed at reducing the development of acne scarring are integral to prevent the associated debilitating psychosocial effects that may arise from acne scars.

Conflicts of interest

Dr Tan has acted as a consultant for and/or received grants/honoraria from Bausch, Galderma, Pfizer, Almirall, Boots/Walgreens, Botanix, Cipher, Galderma, Novan, Novartis, Promius, SUN, and Vichy. Dr Beissert has acted as an advisor for AbbVie Deutschland GmbH & Co, Actelion Pharmaceuticals GmbH, Allmirall-Hermal GmbH, Amgen GmbH, Celgene GmbH, Galderma Laboratorium GmbH, Janssen-Cilag GmbH, Leo Pharma GmbH, Lilly Deutschland GmbH, Menlo Therapeutics, MSD Sharp & Dohme GmbH, Novartis Pharma GmbH, Pfizer Pharma GmbH, Sanofi-Aventis Deutschland GmbH, and UCB Pharma GmbH and has received speaker honorarium from Novartis Pharma GmbH, AbbVie, MSD, Pfizer, Janssen-Cilag, Roche-Posay, Actelion, GSK, BMS, Celgene, Allmirall, and Hexal-Sandoz. Dr Cook-Bolden has acted as an advisor, consultant, investigator, and/or speaker and has received grants/honoraria from Almirall, Cassiopea, Foamix Pharmaceuticals, Galderma, and Ortho Dermatologics. Dr Chavda is an employee of Galderma. Dr Harper has acted as an advisor, consultant, and/or speaker and has received honoraria from Almirall, BioPharmX, Cassiopeia, Cutanea, Cutera, Dermira, EPI Health, Galderma, LaRoche-Posay, Ortho Dermatologics, Sol-Gel Technologies, Sun, and Vyne. Dr Hebert has acted as an advisor, consultant, investigator, and/or speaker and has received grants/honoraria from Allergan, Cassiopea, Galderma, GSK, La Roche-Posay, Novan, Ortho Dermatologics, Ortho Dermatologics, Regeneron Sanofi, and Vyne. Dr Lain has acted as an advisor, consultant, investigator, and/or speaker and has received grants/honoraria from AbbVie, Aclaris Therapeutics Inc, Allergan Inc, Almirall, AstraZeneca, Athenix, Biopelle Inc, BioPharmX, Biorasi LLC, BMS, Brickell Biotech Inc, Cassiopea SpA, Celgene, Cellceutix, ChemoCentryx, Cutanea Life Sciences, Demira, Dow Pharmaceutical Sciences Inc, Dr Reddy's Laboratory, Eli Lilly and Company, Gage Development Company LLC, Galderma Laboratories L.P., Galderma, Hovione, Kadmon Corporation LLC, La Roche-Posay, Leo Pharma, MedImmune, Menlo Therapeutics, Moleculin LLC, Neothetics, Nielsen Holdings N.V, Novartis, Othro Dermatologics, Pfizer Inc, Promius Pharma LLC, Sebacia Inc, Sienna Labs Inc, SkinCeuticals LLC, Sol-Gel Technologies, UCB, and Valeant Pharmaceuticals North America LLC. Dr Layton has acted as an advisor, consultant, investigator, and/or speaker and has received grants/honoraria from Galderma, GSK, L'Oreal, La Roche-Posay, Origimm, Leo Pharma, and Proctor & Gamble. Dr Rocha has acted as an advisor and/or speaker and has received honoraria from Eucerin, Galderma, Johnson & Johnson, and Leo Pharma. Dr Weiss has acted as an advisor, consultant, investigator, and/or speaker and has received grants/honoraria from Almirall, Bausch, Cassiopea, Cutera, EPI Health, Foamix, Galderma, and Ortho Dermatologics. Dr Dréno has acted as an advisor, consultant, and/or speaker and has received honoraria from BMS, Galderma, La Roche-Posay, Merck Serono, Pierre Fabre, and Sanofi.

Acknowledgments

This research was sponsored by Galderma. Medical writing and editorial assistance was provided by Kantar Health (France) and funded by Galderma. Local specialized qualitative researchers conducted in-depth interviews. The authors thank the study participants for their participation in this study.

Footnotes

Funding sources: Supported by Galderma.

IRB approval status: Reviewed and approved by the Kantar Health internal institutional review board/ethics committee.

References

- 1.Tan J.K.L., Tang J., Fung K., et al. Development and validation of a comprehensive acne severity scale. J Cutan Med Surg. 2007;11(6):211–216. doi: 10.2310/7750.2007.00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Layton A.M., Henderson C.A., Cunliffe W.J. A clinical evaluation of acne scarring and its incidence. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19(4):303–308. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1994.tb01200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dréno B, Bettoli V, Torres Lozada V, Kang S. Paper presented at: 23rd European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV) Congress.October. 8-12; 2014. on behalf of the Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne. Evaluation of the prevalence, risk factors, clinical characteristics, and burden of acne scars among active acne patients who have consulted a dermatologist in Brazil, France and the USA. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fife D. Practical evaluation and management of atrophic acne scars: tips for the general dermatologist. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2011;4(8):50–57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tasoula E., Gregoriou S., Chalikias J., et al. The impact of acne vulgaris on quality of life and psychic health in young adolescents in Greece. Results of a population survey. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87(6):862–869. doi: 10.1590/S0365-05962012000600007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goodman G.J. Treating scars: addressing surface, volume, and movement to expedite optimal results. Part 2: more-severe grades of scarring. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38(8):1310–1321. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2012.02439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Layton A., Dréno B., Finlay A.Y., et al. New patient-oriented tools for assessing atrophic acne scarring. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2016;6(2):219–233. doi: 10.1007/s13555-016-0098-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tan JCR, Leclerc M, York J, Dréno B. Paper presented at: 29th European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV) Virtual Congress; October 29-31; 2020. The burden of acne scars: a qualitative study on patient experience. Vienna, Austria. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tong A., Sainsbury P., Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tan JCR, Le Calve P, Young R, Gaultier L, Dréno B. Paper presented at: 29th European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV) Virtual Congress; October 29-31; 2020. Impact of atrophic acne scars on quality of life. Vienna, Austria. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finlay A.Y., Khan G.K. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)–a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19(3):210–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1994.tb01167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oosthuizen P., Lambert T., Castle D.J. Dysmorphic concern: prevalence and associations with clinical variables. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1998;32(1):129–132. doi: 10.3109/00048679809062719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dréno B., Tan J., Kang S., et al. How people with facial acne scars are perceived in society: an online survey. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2016;6(2):207–218. doi: 10.1007/s13555-016-0113-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cotterill J.A., Cunliffe W.J. Suicide in dermatological patients. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137(2):246–250. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1997.18131897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tan J., Thiboutot D., Gollnick H., et al. Development of an atrophic acne scar risk assessment tool. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(9):1547–1554. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agrawal D.A., Khunger N. A morphological study of acne scarring and its relationship between severity and treatment of active acne. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2020;13(3):210–216. doi: 10.4103/JCAS.JCAS_177_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thomas C.L., Kim B., Lam J., et al. Objective severity does not capture the impact of rosacea, acne scarring and photoaging in patients seeking laser therapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(2):361–366. doi: 10.1111/jdv.13945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]