Abstract

A free-ranging lynx (Lynx lynx) was shot because of its abnormal behavior. Histopathological examination revealed a nonsuppurative meningoencephalitis. In situ hybridization, immunohistochemistry, and reverse transcriptase PCR analysis showed the presence of Borna disease virus infection in the brain. To our knowledge, this is the first confirmed case of Borna disease in a large felid.

Borna disease virus (BDV) is a neurotropic, nonsegmented RNA virus of negative polarity and so far the only member of the family Bornaviridae within the order Mononegavirales (12, 13). The host spectrum of BDV is very broad and includes horses, sheep, cattle, cats, rabbits, and ostriches (8, 22, 25, 32). Natural BDV infection in these species usually causes a severe neurological syndrome called Borna disease (BD), morphologically manifested as a nonsuppurative encephalomyelitis with a predilection for the limbic system, the basal ganglia, and the brain stem (15).

During the last decade, several reports concerning the existence of human BDV infections have been published. Findings of BDV-specific antibodies, BDV antigen, and BDV RNA in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) of patients with affective disorders and schizophrenia suggest a link between BDV and certain human neuropsychiatric diseases (7, 9, 19, 31, 33). In addition, isolation of BDV from the PBMCs of patients with psychiatric disorders was recently reported (10, 28). However, since evidence for a direct etiological role of BDV has not been presented to date, the importance of BDV in the pathogenesis of such diseases remains to be elucidated.

Since the source of human BDV infections is unknown, it is important to investigate the epidemiology of BDV. Its wide host range, as well as the high level of sequence homology between isolates from different animal species (5, 34), suggests the possibility that BD may be a zoonosis. Although a wildlife reservoir for BDV has been assumed to exist, formal evidence for this notion is still lacking. Here we report on a case of BD in a free-ranging Swedish lynx (Lynx lynx). To our knowledge, this is the first time that natural BDV infection has been detected in a wild felid.

An adult male lynx was shot in the county of Gävleborg, Sweden, on 3 July 1999 because of its abnormal behavior. The animal was found lying in the ventral position in high grass beside a path, close to a fence limiting a grazing pasture for sheep. It showed no reaction when it was first approached by a farmer and his livestock and later on by a hunter. A video recording was made by the hunter, showing a highly apathetic animal that had a staring, expressionless gaze and that was seemingly unaware of its environment.

The animal was shot in the head at close range and submitted within 2 days to the National Veterinary Institute for postmortem examination. The lynx was found to be emaciated and infested with a small number of ticks on the head and neck. The mandibular, cervical, and iliac lymph nodes were slightly enlarged. There was severe bullous pulmonary emphysema, multiple white-yellowish subpleural nodules along the dorsal side of the cranial and diaphragmatic lobes, and two minor dark red pneumonic foci in the left middle lobe. The stomach was empty. The contents of the small intestine were normal apart from a slight infection with ascarids. Except for slight lesions due to the shot, no macroscopic abnormalities were observed in the brain.

A small amount of blood could be collected from the main blood vessels and from the heart; it was stored at −80°C. Three ticks present on the head and neck were collected and stored at −80°C. The brain was removed intact and was divided into two halves by a longitudinal cut through the midline of the corpus callosum and the brain stem. One half was stored at −80°C for later determination of viral RNA by reverse transcriptase (RT) PCR. The other half was fixed in buffered 10% formalin and was cut into serial coronal sections that included the frontal cortex, basal ganglia, parietal cortex, thalamus, hippocampus, lateral cerebellar hemisphere, and pons. Samples of various internal organs were also divided into two parts, one of which was frozen at −80°C and the other of which was fixed in buffered 10% formalin. After the samples were embedded in paraffin, 4-μm-thick sections of the various brain regions as well as internal organs were cut and stained with hematoxylin-eosin (HE) and Giemsa for light microscopy.

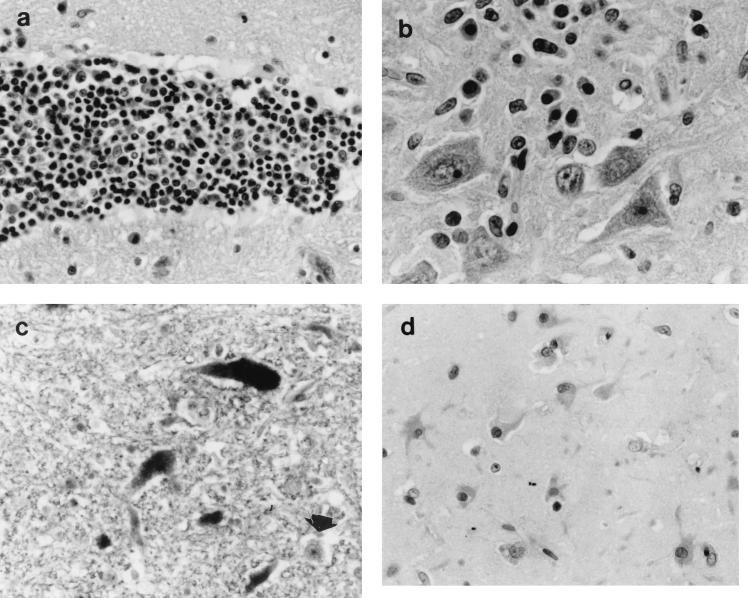

Histopathological examination revealed a suppurative bronchopneumonia in the left middle lobe. The multiple subpleural nodules observed macroscopically were found to be foci of foamy macrophages (endogenous lipid pneumonia). In the brain, a moderate to severe nonsuppurative meningoencephalitis was present in all sections, but predominantly in the basal ganglia, thalamus, and pons. The inflammatory reaction was characterized by mononuclear adventitial cuffing, neuronophagia, and scattered microglial nodules. Lymphocytes and plasma cells were observed in the neural parenchyma, sometimes close to neurons (Fig. 1a and b).

FIG. 1.

(a) Mononuclear adventitial cuff in the hippocampus. HE staining. Magnification, ×360. (b) Plasma cells in the vicinity of neurons in the hippocampus. HE staining. Magnification, ×576. (c) Neurons in the pons showing positive hybridization signals for BDV p24 (dark staining of nucleus and cytoplasm). The arrowhead points to a negative neuron. In situ hybridization with a digoxigenin-labeled cRNA probe (no counterstain). Magnification, ×360. (d) Astrocytes in the hippocampus showing positive immunostaining with a polyclonal antibody against BDV. APAAP method with hematoxylin as the counterstain. Magnification, ×360.

Since the histopathological picture in the brain was found to be strikingly similar to that observed in feline BD (21, 22, 24), we performed immunohistochemistry (IHC) and in situ hybridization (ISH) to check for intracerebral BDV infection. ISH was performed with paraffin-embedded sections from the brain (cerebellar hemisphere and pons) as described previously (1). In brief, a digoxigenin-labeled antisense cRNA probe specific for the BDV p24 gene was prepared by in vitro transcription from a 392-bp PCR fragment cloned from a cat with natural BD. Hybridization was performed in a humid chamber at 65°C overnight. Following the performance of washing steps and treatment with RNase A, detection was performed with an alkaline phosphatase-conjugated antidigoxigenin antibody and two color substrates, nitroblue tetrazolium and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate. After color development, the sections were mounted in glycerol-gelatin, without counterstaining.

Positive hybridization signals for BDV p24 were detected both in the nuclei and in the cytoplasms of numerous neurons and glial cells in the brain sections examined (Fig. 1c). There was a correlation between the presence of inflammatory lesions and positively labeled cells.

IHC for the detection of BDV antigen was likewise performed with paraffin-embedded sections of the brain (cerebellar hemisphere, pons, thalamus, hippocampus). After dewaxing and permeabilization with proteinase K (Boehringer Mannheim) at a concentration of 100 μg/ml at 37°C for 15 min, nonspecific protein binding was minimized by incubation for 30 min with 20% normal goat serum (Dakopatts) in 0.05 M Tris-buffered saline (pH 7.6). As the primary antibody, rabbit BDV-specific serum LL2 (20) was used. Sections were incubated with the primary antibody at various dilutions (1:100 to 1:500) overnight at 4°C. The alkaline phosphatase-antialkaline phosphatase (APAAP) method was used for immunostaining, with a mouse anti-rabbit antibody (Immunotech) used as the secondary antibody, a goat anti-mouse antibody (Immunotech) used as the bridging antibody, fast red used as the chromogen, and hematoxylin used as the counterstain.

The immunohistochemical staining followed a pattern similar to that determined from the ISH signals: positive labeling of neurons and glial cells in regions with inflammatory lesions (Fig. 1d). Positive immunostaining was observed predominantly in the cytoplasm, although small nuclear foci were sometimes labeled.

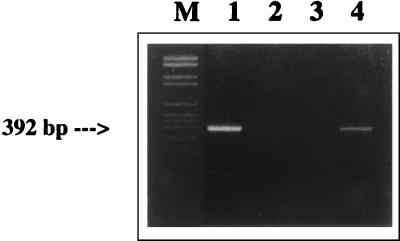

In order to confirm the results of ISH and IHC, we performed RT PCR with BDV-specific primers with two brain tissue samples (cerebral cortex, pons) and samples from the three ticks collected from the lynx. Total RNA was extracted with the Trizol reagent (Life Technologies), as recommended by the manufacturer. One microgram of total RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA with Superscript II (Life Technologies) by using oligo(dT)12–18 (Life Technologies) as a primer. The cDNA was amplified by a nested PCR as described previously (3). In brief, two sets of primers specific for a fragment of the BDV p24 gene were used: for the first round of PCR, 5′-TGA CCC AAC CAG TAG ACC A-3′ at nucleotides 1387 to 1405 and 5′-GTC CCA TTC ATC CGT TGT C-3′ at nucleotides 1865 to 1847; for the second round of PCR, 5′-TCA GAC CCA GAC CAG CGA A-3′ at nucleotides 1443 to 1461 and 5′-AGC TGG GGA TAA ATG CGC G-3′ at nucleotides 1834 to 1816. The samples were processed through 30 cycles during each round of PCR (94°C for 60 s, 58°C for 60 s, and 72°C for 60 s, with a final extension step of 10 min at 72°C) in a Perkin-Elmer Cetus DNA thermal cycler. The PCR products were visualized after electrophoresis in a 2% agarose gel by staining with ethidium bromide.

A fragment of the predicted size (392 bp) was obtained after the second round of PCR with both brain samples (Fig. 2, lane 4). No positive PCR products were obtained from the three ticks (Fig. 2, lane 2). The nested PCR product from the pons region was purified with the Wizard PCR purification kit (Promega) and was cloned into the pGEM-T vector (Promega). Both strands of three clones were sequenced with an automatic fluorescence-activated DNA sequencer. The sequence data were then analyzed with the MegAlign program of the DNA Star software package (DNA Star Inc.). A comparison was made between the sequence obtained from the lynx and the sequences of well-characterized BDV reference strains He/80 and BDV V. The sequences obtained from naturally infected cats and horses were also included in the analysis, as was a recent human isolate (RW98) (28).

FIG. 2.

Gel showing amplification of a 392-bp fragment following nested RT PCR. Lanes: M, molecular DNA marker (DNA VI; Boehringer Mannheim); 1, cerebral cortex from a Swedish domestic cat (cat O.436/92); 2, ticks collected from the diseased lynx; 3, water control; 4, pons from the diseased lynx.

The sequence from the lynx was found to be closely related to the BDV sequences previously obtained from naturally infected animals, as well as to the sequences of the two reference strains. A slightly higher degree of homology to BDV V than to He/80 was found (Table 1). Twelve and seven single-base differences compared to the sequences of He/80 and BDV V, respectively, were found. Most of these changes, however, were silent. An alignment of the predicted amino acid sequences showed two substitutions in the lynx sequence compared to the sequences of BDV V and He/80 (Table 1). The first one was from glutamine (Gln) to glutamic acid (Glu) at position 35 (corresponding to position 92 in the full-length protein); the second was from glutamic acid (Glu) to valine (Val) at position 102 (corresponding to position 159 in the full-length protein).

TABLE 1.

Lynx BDV p24 sequence compared to those of reference strains He/80 and BDV V and some p24 sequences from various hosts (cat, horse, human)

| Isolate | % Nucleic acid identity | % Amino acid identity | Positiona | Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| He/80 | 96.9 | 98.5 | 35 | Gln→Glu |

| 102 | Glu→Val | |||

| BDV V | 97.7 | 98.5 | See data for He/80 | See data for He/80 |

| Cat O.436/92b | 97.4 | 97.7 | 35 | Gln→Glu |

| 92 | Met→Thr | |||

| 102 | Glu→Val | |||

| Cat Ac | 96.2 | 96.2 | 14 | Asn→Ser |

| 16 | Glu→Gly | |||

| 35 | Gln→Glu | |||

| 46 | Arg→His | |||

| 102 | Glu→Val | |||

| Horse 1d | 96.4 | 96.9 | 35 | Gln→Glu |

| 46 | Arg→His | |||

| 92 | Met→Thr | |||

| 102 | Glu→Val | |||

| Wt1e | 96.2 | 98.5 | See data for He/80 | See data for He/80 |

| RW98f | 95.4 | 98.5 | See data for He/80 | See data for He/80 |

A comparison of the lynx sequence and two p24 sequences obtained from Swedish domestic cats with BD revealed the presence of three and five amino acid substitutions, respectively (Table 1). There were also several amino acid substitutions compared to the sequence obtained from a Swedish horse. In contrast, a relationship similar to that with He/80 and BDV V was found between the sequence from the lynx and a German equine isolate, as well as a human isolate (also from Germany) (Table 1). Overall, the phylogenetic analysis of the p24 sequence from the lynx confirmed previous observations of the high degree of sequence homology between BDV isolates from different animal species (34).

Finally, we tested blood obtained from the main vessels and the heart of the lynx for the presence of BDV-specific antibodies using an indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with recombinant BDV p24 and p40 proteins as described previously (3). Blood samples from two healthy lynx were analyzed simultaneously. All lynx samples were tested in duplicate wells in twofold dilutions from 1:5 to 1:80. Serum from a cat experimentally infected with BDV was used as a positive control.

No BDV-specific antibodies could be detected in any of the lynx blood samples. This may be due either to an insensitivity of the assay system (originally developed for the detection of BDV-specific antibodies in horses) or to a real absence of antibodies. It is known that horses that die of acute BD are sometimes seronegative, and even ponies intracranially inoculated with BDV may fail to develop antibodies (18). In addition, domestic cats with BD may frequently be seronegative or show very low titers (23).

We have previously shown that domestic cats in Sweden affected by a neurological disorder called staggering disease (renamed feline BD) are infected with BDV (1, 21, 23). Further evidence for the existence of feline BDV infections has been provided by independent research groups in Austria, Switzerland, Japan, and Great Britain (11, 26, 28, 30). In large felids, cases of nonsuppurative encephalomyelitis of unknown but presumed viral etiology have been reported from different parts of the world (14, 35). Although some of these cases share both clinical and histopathological features with BD, BDV has not been identified as the cause of the disease.

In this note we report for the first time a confirmed case of BD in a large felid, a lynx. Because it was a free-ranging animal, the duration of illness is unknown. However, the emaciated condition of the lynx suggests that it had been unable to hunt for food for several weeks. When it was found, the animal seemed incapable of movement. This could have been due either to paralysis or to general weakness. The absence of fear of strangers and the staring gaze are behavioral changes reminiscent of those observed in domestic cats with BD (21).

Histopathologically, the lesions in the brain are consistent with those previously described in feline BD (21, 22). A special feature of feline BD is the presence of plasma cells in close proximity to neurons (22, 24). This was also observed in the lynx, especially in the hippocampus (Fig. 1b). ISH and IHC confirmed the presence of BDV in numerous neurons and glial cells, as previously reported in cats and horses with BD (1, 4).

The lynx was found in a geographical area where cases of feline BD are known to occur (A.-L. Berg, unpublished data). Although the epidemiology of feline BD is largely unknown, some risk factors have been identified. In a previous case-control study, we showed that feline BD has a predominantly rural or woodland distribution, that affected cats are more likely to be males than females and are more likely to be intact than neutered, and that affected cats are more likely than not to have hunted mice (2). The identification of exposure to mice by hunting as a risk factor suggests the possibility that rodents may be subclinically infected and act as virus carriers.

In Fennoscandia, the lynx mainly feeds on hares and wild deers, but up to 12% of its diet is composed of rodents (6, 29). Recently, rodents have been implicated as a reservoir for orthopoxvirus and as a possible source of infection for predatory wild carnivores (37). Five of 17 (29%) free-ranging lynx from northern Sweden have shown positive reactions for antiorthopoxvirus antibodies, and predation on rodents and occasionally cats has been suggested as a potential route of infection (36). In Finland, domestic cats were indeed shown to represent 4 to 7.5% of the lynx diet in winter (29). Therefore, the possibility of an oral infection through predation must be considered in this case.

Speculation that an arthropod vector may act as a carrier of BDV has so far not been corroborated. The negative result of the tick analysis in the present study does not support this theory either, although it cannot be completely ruled out. An infection through direct contact is improbable: the lynx is a solitary animal, with intraspecific contacts between males and females mainly during the rutting season (in February and March) and between mother and kittens during the year following the birth (16, 17).

An autopsy study that included >400 animals showed that the most common causes of death in free-ranging Swedish lynx are traffic accidents and sarcoptic mange (M.-P. Degiorgis, C. Hård of Segerstad, C. Bröjer, A. Bignert, S. Bornstein, D. Christensson, D. Gavier-Widén, D. S. Jansson, and T. Mörner, unpublished data). The case reported here was the only case of BD detected in this set of autopsy study material, which suggests that BD is not a common disease in Swedish lynx. However, further serological investigations are necessary to assess the prevalence of BDV infection in this species.

In conclusion, the finding of BD in a free-ranging carnivore shows that the host spectrum of BDV is even wider than was previously thought. Attention should be paid to wild rodents as possible reservoirs of BDV. Many questions linger over the epidemiology of BDV: the fact that humans are infected from a still unknown source provides a strong incentive for further epidemiological studies.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequence data reported in this article have been deposited in the GenBank database under accession no. AF200463 (lynx, Sweden), AF201073 (domestic cat O.436/92, Sweden), and AF203970 (horse 1, Sweden).

Acknowledgments

We thank Karl-Gustav Andersson for communicating this interesting case of BD, Hans Hedblom for the video recording, and Hanns Ludwig, Berlin, Germany, for the kind gift of rabbit BDV-specific serum LL2.

Financial support from the Swedish Council for Forestry and Agricultural Research (SJFR), the Swedish branch of Hoechst, and the Swiss National Fund for Scientific Research is gratefully acknowledged.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berg A-L, Berg M. A variant form of feline Borna disease. J Comp Pathol. 1998;119:323–331. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9975(98)80054-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berg A-L, Reid-Smith R, Larsson M, Bonnett B. Case control study of feline Borna disease in Sweden. Vet Rec. 1998;142:715–717. doi: 10.1136/vr.142.26.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berg A-L, Dörries R, Berg M. Borna disease virus infection in racing horses with behavioral and movement disorders. Arch Virol. 1999;144:547–559. doi: 10.1007/s007050050524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bilzer T, Planz O, Lipkin W I, Stitz L. Presence of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and expression of MHC class I and MHC class II antigen in horses with Borna disease virus-induced encephalitis. Brain Pathol. 1995;5:223–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1995.tb00598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Binz T, Lebelt J, Niemann H, Hagenau K. Sequence analysis of the p24 gene of Borna disease virus in naturally infected horse, donkey and sheep. Virus Res. 1994;34:281–289. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(94)90128-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Birkeland K H, Myrberget S. The diet of the lynx Lynx lynx in Norway. Fauna Norv Ser A. 1980;1:24–28. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bode L. Human infections with Borna disease virus and potential pathogenic implications. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1995;190:103–130. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-78618-1_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bode L, Dürrwald R, Ludwig H. Borna virus infections in cattle associated with fatal neurological disease. Vet Rec. 1994;135:283–284. doi: 10.1136/vr.135.12.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bode L, Zimmermann W, Ferszt R, Steinbach F, Ludwig H. Borna disease virus genome transcribed and expressed in psychiatric patients. Nat Med. 1995;1:232–236. doi: 10.1038/nm0395-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bode L, Dürrwald R, Rantam F A, Ferszt R, Ludwig H. First isolates of infectious human Borna disease virus from patients with mood disorders. Mol Psychiatry. 1996;1:200–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bornand J V, Fatzer R, Melzer K, Gonin Jmaa D, Caplazi P, Ehrensperger F. A case of Borna disease in a cat. Eur J Vet Pathol. 1998;4:33–35. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Briese T, Schneemann A, Lewis A J, Park Y S, Kim S, Ludwig H, Lipkin W I. Genomic organization of Borna disease virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:4362–4367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.10.4362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cubitt B, Oldstone C, de la Torre J C. Sequence and genome organization of Borna disease virus. J Virol. 1994;68:1382–1396. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.3.1382-1396.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flir K. Encephalomyelitis bei Grosskatzen. Dtsch Tierärztl Wochenschr. 1973;80:401–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gosztonyi G, Ludwig H. Borna disease—neuropathology and pathogenesis. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1995;190:39–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haglund, B. 1966. De stora rovdjurens vintervanor I. Viltrevy 4.

- 17.Haller H, Breitenmoser U. Zur Raumorganisation der in den Schweizer Alpen wiederangesiedelten Population des Luchses (Lynx lynx) Z Säugetierkd. 1986;51:289–311. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Katz J B, Alstad D, Jenny A L, Carbone K M, Rubin S A, Waltrip R W., II Clinical, serologic, and histopathologic characterization of experimental Borna disease in ponies. J Vet Diagn Invest. 1998;10:338–343. doi: 10.1177/104063879801000405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kishi M, Nakaya T, Nakamura Y, Zhong Q, Ikeda K, Senjo M, Kakinuma M, Kato S, Ikuta K. Demonstration of human Borna disease virus RNA in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. FEBS Lett. 1995;364:293–297. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00406-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ludwig H, Furuya K, Bode L, Klein N, Dürrwald R, Lee D S. Biology and neurobiology of Borna disease viruses (BDV), defined by antibodies, neutralizability and their pathogenic potential. Arch Virol (Suppl) 1993;7:111–133. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-9300-6_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lundgren A-L. Feline non-suppurative meningoencephalomyelitis. A clinical and pathological study. J Comp Pathol. 1992;107:411–425. doi: 10.1016/0021-9975(92)90015-M. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lundgren A-L, Lindberg R, Ludwig H, Gosztonyi G. Immunoreactivity of the central nervous system in cats with a Borna disease-like meningoencephalomyelitis (staggering disease) Acta Neuropathol. 1995;90:184–193. doi: 10.1007/BF00294319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lundgren A-L, Zimmermann W, Bode L, Czech G, Gosztonyi G, Lindberg R, Ludwig H. Staggering disease in cats: isolation and characterization of the feline Borna disease virus. J Gen Virol. 1995;76:2215–2222. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-76-9-2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lundgren A-L, Johannisson A, Zimmermann W, Bode L, Rozell B, Muluneh A, Lindberg R, Ludwig H. Neurological disease and encephalitis in cats experimentally infected with Borna disease virus. Acta Neuropathol. 1997;93:391–401. doi: 10.1007/s004010050630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Malkinson M, Weisman Y, Ashash E, Bode L, Ludwig H. Borna disease in ostriches. Vet Rec. 1993;133:304. doi: 10.1136/vr.133.12.304-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakamura Y, Asahi S, Nakaya T, Bahmani M K, Saitoh S, Yasui K, Mayama H, Hagiwara K, Ishihara C, Ikuta K. Demonstration of Borna disease virus RNA in peripheral blood mononuclear cells derived from domestic cats in Japan. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:188–191. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.1.188-191.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nowotny N, Weissenböck H. Description of feline nonsuppurative meningoencephalomyelitis (“staggering disease”) and studies of its etiology. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1668–1669. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.6.1668-1669.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Planz O, Rentzsch C, Batra A, Batra A, Winkler T, Büttner M, Rziha H-J, Stitz L. Pathogenesis of Borna disease virus: granulocyte fractions of psychiatric patients harbor infectious virus in the absence of antiviral antibodies. J Virol. 1999;73:6251–6256. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.8.6251-6256.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pulliainen E, Lindgren E, Tunkkari P S. Influence of food availability and reproductive status on the diet and body condition of the European lynx in Finland. Acta Theriol. 1995;40:181–196. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reeves N A, Helps C R, Gunn-Moore D A, Blundell C, Finnemore P L, Pearson G R, Harbour D A. Natural Borna disease virus infection in cats in the United Kingdom. Vet Rec. 1998;143:523–526. doi: 10.1136/vr.143.19.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rott R, Herzog S, Fleischer B, Winokur A, Amsterdam J, Dyson W, Koprowski H. Detection of serum antibodies to Borna disease virus in patients with psychiatric disorders. Science. 1985;228:755–756. doi: 10.1126/science.3922055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rott R, Becht H. Natural and experimental Borna disease in animals. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1995;190:17–30. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-78618-1_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sauder C, Müller A, Cubitt B, Mayer J, Steinmetz J, Trabert W, Ziegler B, Wanke K, Mueller-Lantzsch N, de la Torre J C, Grässer F A. Detection of Borna disease virus (BDV) antibodies and BDV RNA in psychiatric patients: evidence for high sequence conservation of human blood-derived BDV RNA. J Virol. 1996;70:7713–7724. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.7713-7724.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schneider P A, Briese T, Zimmermann W, Ludwig H, Lipkin W I. Sequence conservation in field and experimental isolates of Borna disease virus. J Virol. 1994;68:63–68. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.1.63-68.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Truyen U, Stockhofe-Zurwieden N, Kaaden O R, Pohlenz J. A case report: encephalitis in lions. Pathological and virological findings. Dtsch Tierärztl Wochenschr. 1990;97:89–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tryland M, Sandvik T, Arnemo J M, Stuve G, Olsvik Ø, Traavik T. Antibodies against orthopoxviruses in wild carnivores from Fennoscandia. J Wild Dis. 1998;34:443–450. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-34.3.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tryland M, Sandvik T, Mehl R, Bennett M, Traavik T, Olsvik Ø. Serosurvey for orthopoxviruses in rodents and shrews from Norway. J Wild Dis. 1998;34:240–250. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-34.2.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]