Abstract

Background

Beta‐blocker therapy has a proven mortality benefit in patients with hypertension, heart failure and coronary artery disease, as well as during the perioperative period. These drugs have traditionally been considered contraindicated in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Objectives

To assess the effect of cardioselective beta‐blockers on respiratory function of patients with COPD.

Search methods

A comprehensive search of the Cochrane Airways Group Specialised Register (derived from systematic searches of CENTRAL, MEDLINE, EMBASE and CINAHL) was carried out to identify randomised blinded controlled trials from 1966 to August 2010. We did not exclude trials on the basis of language.

Selection criteria

Randomised, blinded, controlled trials of single dose or longer duration that studied the effects of cardioselective beta‐blockers on the forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) or symptoms in patients with COPD.

Data collection and analysis

Two independent reviewers extracted data from the selected articles, reconciling differences by consensus. Two interventions studied were the administration of beta‐blocker, given either as a single dose or for longer duration, and the use of beta2‐agonist given after the study drug.

Main results

Eleven studies of single‐dose treatment and 11 of treatment for longer durations, ranging from 2 days to 16 weeks, met selection criteria. Cardioselective beta‐blockers, given as a single dose or for longer duration, produced no change in FEV1 or respiratory symptoms compared to placebo, and did not affect the FEV1 treatment response to beta2‐agonists. Subgroup analyses revealed no significant change in results for those participants with severe chronic airways obstruction, those with a reversible obstructive component, or those with concomitant cardiovascular disease.

Authors' conclusions

Cardioselective beta‐blockers, given to patients with COPD in the identified studies did not produce adverse respiratory effects. Given their demonstrated benefit in conditions such as heart failure, coronary artery disease and hypertension, cardioselective beta‐blockers should not be routinely withheld from patients with COPD.

Keywords: Humans; Adrenergic beta‐Antagonists; Adrenergic beta‐Antagonists/therapeutic use; Forced Expiratory Volume; Pulmonary Disease, Chronic Obstructive; Pulmonary Disease, Chronic Obstructive/drug therapy; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Are cardioselective beta‐blockers a safe and effective treatment in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease?

Long term treatment with beta‐blocker medication reduces the risk of death in patients with high blood pressure, heart failure and coronary artery disease. But patients who have both COPD and cardiovascular disease sometimes do not receive these medicines because of fears that they may worsen the airways disease. This review of data from 22 randomised controlled trials on the use of cardioselective (heart‐specific) beta‐blockers in patients with COPD demonstrated no adverse effect on lung function or respiratory symptoms compared to placebo. This finding was consistent whether patients had severe chronic airways obstruction or a reversible obstructive component. In conclusion, cardioselective beta‐blockers should not be withheld from patients with COPD.

Background

Beta‐adrenergic blocking agents, or beta‐blockers, are indicated in the management of angina pectoris, myocardial infarction, hypertension, congestive heart failure, cardiac arrhythmia and thyrotoxicosis, as well as to reduce complications in the perioperative period (Beattie 2008; Doughty 1997; Fitzgerald 1991; Freemantle 1999; Heidenreich 1999; IPPSH 1985; JNC 1997; Jones 1980; Kendall 1997; Klein 1994; Koch‐Weser 1984; Lechat 1998; Mangano 1996; McGory 2005; Steinbeck 1992; Wadworth 1991). Despite clear evidence of their effectiveness and mortality benefit, clinicians are often hesitant to administer beta‐blockers in the presence of a variety of common conditions for fear of adverse reactions (Chafin 1999; Egred 2005; Gottlieb 1998; Kennedy 1995; Viskin 1996). Review articles and practice guidelines have often listed asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) as contraindications to beta‐blocker use, citing cases of acute bronchospasm occurring during non‐cardioselective beta‐blocker use (Belli 1995; Craig 1996; JNC 1997; Kendall 1997; O'Malley 1991; Tattersfield 1986; Tattersfield 1990). Cardioselective beta‐blockers, or beta1‐blockers, have over 20 times greater affinity for beta‐1 receptors as for beta‐2 receptors, and theoretically should have significantly less risk for bronchoconstriction (Wellstein 1987).

A Cochrane review demonstrated that cardioselective beta1‐blockers, given to patients with mild to moderate reversible airway disease, do not produce clinically significant adverse respiratory effects (Salpeter 2002). The study was not designed to make recommendations about people with significant chronic airway obstruction because only a few COPD patients met the reversibility criteria for the study. Patients with COPD are at greater risk of ischemic heart disease than asthmatics, so would benefit from the use of beta‐blockers. However, they also have more severe airways obstruction, so may be more sensitive to small changes in FEV1 due to beta‐blockade.

Objectives

To evaluate the effect of cardioselective beta1‐blockers on respiratory function in patients with COPD, as assessed by FEV1 and the incidence of symptoms. Another objective was to evaluate the FEV1 response to beta2‐agonists for those patients treated with beta1‐blockers as compared to placebo.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

A search was performed to identify all relevant published clinical trials that address the effects of cardioselective beta‐blockers on airway function in patients with COPD. Trials were included if they: (1) reported FEV1 measured at rest, either as litres or as a percent of the normal predicted value at baseline and follow‐up, or reported symptoms for study drug and placebo, (2) were randomised, controlled, and single or double‐blinded, and (3) included only subjects with COPD, demonstrated by a baseline FEV1 of < 80% normal predicted value, or as defined by the guidelines of the American Thoracic Society (ATS 1995). Cross‐over trials were considered to be randomised if different interventions were administered in random order. Controlled trials were those with placebo or comparative controls.

The decision was made to evaluate only cardioselective beta1‐blockers in this study as these are the ones most frequently used in clinical practice. Studies were included only if participants had documented COPD, in order to evaluate the effect of cardioselective beta‐blockers in patients with chronic airway obstruction. Only blinded studies were included in order to decrease the risk of reporting bias that is inherent in unblinded studies. It was decided a priori to data extraction that comparative trials studying FEV1 treatment effects of cardioselective beta‐blockers without placebo controls would be included as long as they compared various interventions in a blinded randomised manner. Sensitivity analysis was performed to evaluate the effect of including these studies. For studies that evaluated symptoms, only those that have placebo controls for comparison to active treatment were included.

Types of participants

Participants studied were those with COPD, defined as a disease state with chronic airway obstruction according to the guidelines of the ATS (ATS 1995), or with a baseline FEV1 of less than 80% normal predicted value. Participants were not included or excluded on the basis of reversibility of their airway obstruction.

Types of interventions

The main intervention studied was the use of intravenous or oral cardioselective beta‐blockers versus placebo or other interventions, given either as a single dose or for an extended period. A second intervention studied was the administration of a beta2‐agonist, either intravenously or by inhalation, given after the study medication or placebo. For single‐dose trials the beta‐agonist was given one hour after the administration of an intravenous agent, and three to six hours after an oral agent was given.

Types of outcome measures

Two investigators (SS, TO) independently extracted data on three outcomes: (1) the change in FEV1 from baseline in response to study group or placebo, (2) FEV1 response to beta2‐agonist administered after placebo or study drug, and (3) reported symptoms during the trial, such as wheezing, dyspnea, or COPD exacerbation, for study drug or placebo.

For single‐dose trials of oral medications the FEV1 measurements were recorded from one to six hours after drug administration, with all trials measuring FEV1 at least three hours after treatment was given. When intravenous medications were used, the FEV1 was measured repeatedly for one hour after the treatment was given. For trials using beta2‐agonists, FEV1 measurements were taken 10 minutes after intravenous beta‐agonist and 20‐30 minutes after inhalation of the agent.

Respiratory symptoms were measured according to a self‐reporting system used for each trial, and were reported as the number of patients with symptoms. For single‐dose trials respiratory symptoms were described as wheezing, dyspnea or breathlessness. For trials of longer duration patients were to record symptoms such as acute shortness of breath, increased respiratory symptoms, asthma attacks or COPD exacerbations.

Search methods for identification of studies

Two investigators (SS, TO) jointly developed search strategies, with the help of an information service librarian and the Cochrane Airways Group Trial Search Co‐ordinator. A search was performed using the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and the Cochrane Airways Group Specialised Register to identify blinded controlled trials on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The Specialised Register is derived from systematic searches of bibliographic databases including CENTRAL, MEDLINE, EMBASE and CINAHL, and hand‐searching of respiratory journals and meeting abstracts (please see the Airways Group Module for further details). All records in the Specialised Register coded as 'COPD' were searched using the following terms:

(adrenergic* and antagonist*) or (adrenergic* and block*) or (adrenergic* and beta‐receptor*) or (beta‐adrenergic* and block*) or (beta‐blocker* and adrenergic*) or (blockader* or Acebutolol or Alprenolol or Atenolol or Betaxolol or Bisoprolol or Bupranolol or Butoxamine or Carteolol or Celiprolol or Dihydroalprenolol or Iodocyanopindolol or Labetalol or Levobunolol or Metipranolol or Metoprolol or Nadolol or Oxprenolol or Penbutolol or Pindolol or Practolol or Propranolol or Sotalol or Timolol)

This search was adapted for use in CENTRAL and combined with the Airways Group 'COPD' search (see Appendix 1). The most recent searches were conducted in August 2010.

Trials were not excluded on the basis of language. The search was further augmented by scanning references of identified articles or reviews, and of abstracts at clinical symposia.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two investigators (SS, TO) independently evaluated studies for inclusion and the observed percentage agreement between raters was calculated. Studies were evaluated if they gave intravenous or oral cardioselective beta‐blockers, either as a single dose or for an extended period.

Data extraction and management

Two independent reviewers (SS, TO) extracted data from the selected articles, reconciling differences by consensus. Only published data from the trials were included in the analysis. No attempts were made to contact the original authors to verify the data or obtain more information, as most of the trials were small and published several years ago. Data from single‐dose trials and those of longer duration were analysed separately.

Measures of treatment effect

The baseline FEV1 used for single‐dose trials was that measured on the study day prior to the administration of study drug. For longer‐duration trials baseline FEV1 measurements were taken prior to the initiation of treatment. For all trials in which more than one FEV1 measurement was reported after administration of the study drug the lowest FEV1 was used for the analysis.

To estimate the net treatment effect, the ratio of the lowest measured FEV1 value seen after study drug to baseline FEV1 were measured for both placebo and active treatment, and recorded as the percent change from baseline. The treatment response was then compared to the placebo response. For those studies without placebo controls (see Characteristics of included studies) the treatment response for each intervention was measured and the placebo response was estimated from the available placebo‐controlled trials. Sensitivity analysis was performed to evaluate the effect of including these trials.

Results for respiratory symptoms were measured as a risk difference, by subtracting the number of participants with symptoms in the placebo group from the number of those with symptoms in the treatment group. The risk differences were then pooled using the fixed‐effects model for dichotomous outcomes.

Dealing with missing data

For those trials that did not report the standard deviation (SD) for the distribution of study results, the average SD was obtained from the available information and calculated separately for placebo and treatment responses. This pooled SD was used for all trials that did not provide SD data (see Characteristics of included studies). Sensitivity analyses were performed to evaluate the effect of including these trials, by using the lowest and highest available SD in place of the pooled SD, and also by excluding these trials from the analysis.

Assessment of heterogeneity

In order to test for heterogeneity between studies, the chi‐squared was calculated for the assumption of homogeneity, with the statistical significance set at p ≤ 0.1.

Data synthesis

The net treatment effects for each of the FEV1 analyses were recorded as the mean percent change from baseline with SD, and pooled to get a weighted average of the study means using the random‐effects model for continuous outcomes (DerSimonian‐Laird method) (DerSimonian 1986). Confidence intervals (CI) with 95% significance were obtained for the pooled study means. The random‐effects model was used as there was evidence of potential inter‐study heterogeneity in some of the analyses. The results using the random‐effects model were then compared to that using the fixed‐effects model for continuous outcomes (Mantel‐Haenszel method) (Mantel 1959; Yusuf 1985).

In order to evaluate the response to beta2‐agonist given after active treatment or placebo, the new baseline used was the FEV1 taken after study drug but prior to beta‐agonist. The net treatment effect was estimated by calculating the ratio of FEV1 measured after agonist to the new baseline for both placebo and active treatment, and then comparing the treatment‐agonist response to the placebo‐agonist response.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

A subgroup analysis was performed to evaluate the response of patients with severe COPD, as defined by a mean baseline FEV1, for the group, of less than 1.4 litres or less than 50% normal predicted value. Another subgroup analysis evaluated the treatment response of participants known to have reversible airway obstruction, documented by an increase in FEV1 of at least 15% to beta‐agonist stimulation. A third analysis evaluated the response for those known to have comorbid cardiovascular conditions such as hypertension, angina or heart failure.

In each of the analyses that demonstrated evidence for inter‐study heterogeneity, a sensitivity analysis was performed to evaluate potential reasons for the variance.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The database search identified 287 potentially relevant articles. After review of the articles and bibliographies, 44 trials of beta‐blockers in patients with COPD were found. Of these, 22 met inclusion criteria: 11 gave information on single‐dose studies (Adam 1982; Anderson 1980; Beil 1977; Dorow 1986b; Sinclair 1979;Macquin‐Mavier 1988; McGavin 1978Perks 1978; Schanning 1976; Sorbini 1982von Wichert 1982; ), and 11 provided data on treatment of longer duration (Butland 1983; Chang 2010; Dorow 1986a; Fenster 1983; Fogari 1990; Hawkins 2009; Lammers 1985a; Ranchod 1982; Tivenius 1976; van der Woude 2005; Wunderlich 1980). Two new trials have been added to this update (Hawkins 2009; Chang 2010). Inter‐rater agreement for study eligibility was 95%. Of the single‐dose trials, four provided appropriate FEV1 data and nine provided placebo controls for symptom analysis. Of the trials of longer duration, seven were used for FEV1 analysis and ten for symptoms. The FEV1 response to beta2‐agonists were recorded in two single‐dose trials (Adam 1982; Sinclair 1979) and in three longer duration trials (Fogari 1990; Hawkins 2009; van der Woude 2005).

See Characteristics of included studies for details of studies meeting the eligibility criteria of this review.

Excluded studies

Trials were excluded for the following reasons: eight trials evaluated nonselective beta‐blockers only (Addis 1976; Anavekar 1982; Chester 1981; George 1983; Meier 1966a; Nordstrom 1975; Ulmer 1976; Wettengel 1970), one study was a duplicate trial (Meier 1966b), two studies were not randomised (Abraham 1981; Quan 1983), five were not blinded (Camsari 2003; Dal Negro 1981; Dal Negro 1986; Dorow 1984; Dorow 1986c), two did not provide FEV1 data or placebo‐controls (Clague 1984; Jabbour 2010), and four were reviews of other trials (Johnsson 1976; Lois 1997; Lois 1999; van Herwaarden 1983).

Risk of bias in included studies

Most of the studies evaluated were small cross‐over trials that included a wash‐out period between treatment groups. Many were performed 20 or 30 years ago, and the randomisation process was not described in detail. Some of the trials were single‐blind instead of double‐blind. Some of the trials did not have placebo controls or provide individual study SDs for the FEV1 treatment effect, and one study merely evaluated different doses of a single drug compared to baseline controls. Sensitivity analyses were performed to evaluate the effect of including these trials.

Effects of interventions

Cardioselective beta‐blockers included in the study were atenolol, metoprolol, bisoprolol, practolol, celiprolol and acebutolol (See Table 1, Beta‐blocker Categories).

1. Beta‐blocker Categories.

| Nonselective (‐ ISA) | Nonselective (+ISA) | Selective (‐ISA) | Selective (+ ISA) |

| Propranolol | Oxprenolol | Atenolol | Celiprolol (+ alpha block) |

| Timolol | Pindolol | Metoprolol | Acebutolol |

| Nadolol | Dilevalol | Bisoprolol | Xamoterol |

| Sotolol (antiarrhythmic) | Prenalterol | Practolol | |

| Ibutomide (+ alpha block) | Labetolol (+ alpha block) | Esmolol | |

| Pafenolol | |||

| Tolamolol | |||

| Bevantolol (+ alpha agonist) |

Single‐Dose Treatment Results:

Eleven studies on single‐dose treatment included 131 patients, 80% of whom were men. There was an average of 11.9 patients per study, and the dropout rate was 1.5%. From the available information the mean age of participants was 53.8 (+/‐ 11.1) years. These baseline characteristics were the same for the placebo and treatment groups because all of the trials were crossover by design. The baseline FEV1 measured in the treatment group was 1.64 (+/‐ 0.63) litres, and in the placebo group was 1.66 (+/‐ 0.64) litres.

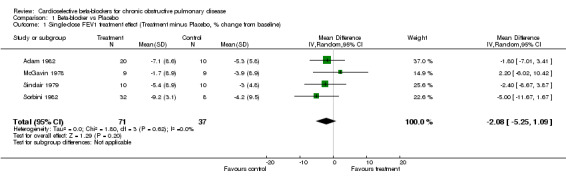

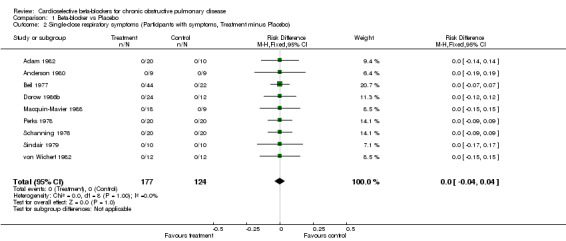

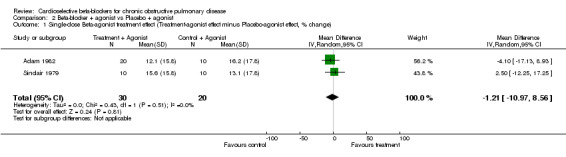

Single doses of cardioselective beta‐blockers were not associated with a change in FEV1 compared to placebo or to baseline controls with a mean difference (MD) of ‐2.08% (95% CI ‐5.25 to 1.09). No increase in respiratory symptoms were seen for beta1‐blockers compared to placebo in any of the trials, with a risk difference (RD) of 0.0% (95%CI ‐0.04 to 0.04). In the two trials that measured response to inhaled beta2‐agonist after treatment and after placebo (Adam 1982; Sinclair 1979), there was no significant change in the net treatment effect (MD ‐1.21%; 95% CI ‐10.97 to 8.56).

Longer Duration Treatment Results:

Data from 11 studies involving 185 participants and 1,436 patient‐weeks were evaluated for treatment effects of longer duration ranging from 2 days to 16 weeks, with a mean trial duration of 5.3 weeks. There was an average of 16.8 participants in each study (78% of whom were men), with a 4.5% dropout rate. The average baseline FEV1 in the treatment group was 1.81 (+/‐ 0.72) litres, and for the placebo group was 1.80 (+/‐ 0.73) litres.

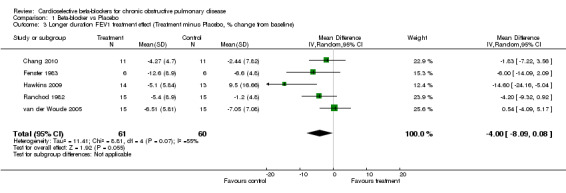

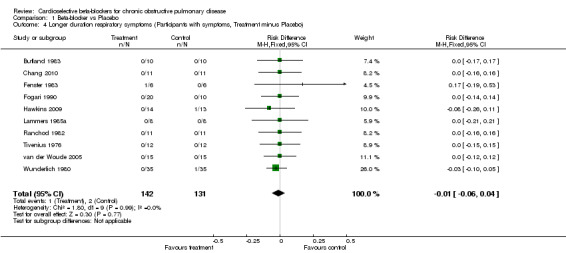

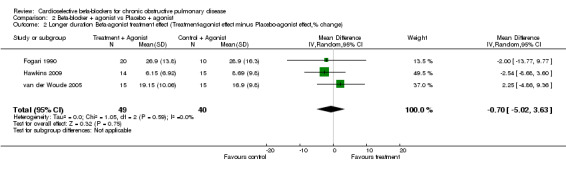

When cardioselective beta‐blockers were compared to placebo, there was no significant change in FEV1 treatment effect (MD ‐2.73; 95% CI ‐6.03 to 0.57) or respiratory symptoms (RD ‐0.01; 95% CI ‐0.06 to 0.04). In the three trials that measured FEV1 response to inhaled beta2‐agonist after treatment and placebo (Fogari 1990; Hawkins 2009; van der Woude 2005), there was no significant difference in the net treatment effect after treatment compared to placebo (MD ‐0.70; 95% CI ‐5.02 to 3.63).

Two new trials have been added to this update (Hawkins 2009; Chang 2010). One trial (Hawkins 2009) showed a statistically significant reduction in FEV1 for treatment compared with placebo (MD ‐14.6%; 95% CI ‐24.16 to ‐5.04). In this trial, the placebo group had a 10% increase in FEV1 over the course of the study, possibly because the baseline FEV1 before treatment was lower in the placebo group (1.26 L) compared with the treatment group (1.37 L). Treatment had no effect on respiratory symptoms or response to subsequent beta2‐agonists. The other trial added to this update (Chang 2010) found no significant effect of treatment on FEV1, respiratory symptoms or bronchodilator response. No other trial in the meta‐analysis showed significant results for FEV1 treatment effect, symptoms, or beta2‐agonist response.

Inter‐study Heterogeneity:

There was minimal inter‐study variance in the measurement of FEV1 for single‐dose studies (p = 0.62), or for respiratory symptoms in single‐dose studies (p = 1) and longer‐duration trials (p = 0.99). For these analyses, the results were the same whether the fixed‐effect model or the random‐effects model were used.

There was evidence for potential inter‐study heterogeneity in the measurement of FEV1 in studies of longer duration (p = 0.07). The results for this analysis were similar when using the random‐effects model (MD ‐2.73; 95% CI ‐6.03 to 0.57) or the fixed‐effects model (MD ‐2.34; 95% CI ‐4.71 to 0.02). One of the trials in this analysis (Hawkins 2009) showed a statistically significant reduction in FEV1 for treatment compared with placebo. When this trial was removed from the analysis, there was no evidence of inter‐study heterogeneity among the remaining trials (p = 0.54).

Subgroup Analyses:

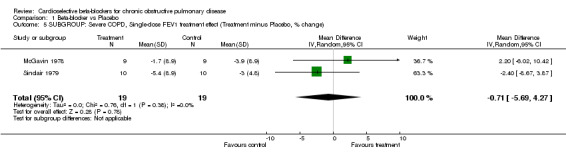

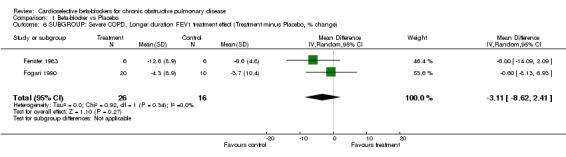

In order to evaluate the effect of treatment in patients with severe chronic airways obstruction, six trials that demonstrated an average baseline FEV1 of < 1.4 litres or < 50% normal predicted values were analysed separately (Butland 1983; Fenster 1983; Fogari 1990; McGavin 1978; Sinclair 1979; Wunderlich 1980). When the analysis was limited to those with severe obstruction there still was no significant difference in FEV1 treatment effect for single‐dose trials (MD ‐0.71; 95% CI ‐5.69 to 4.27) or for longer‐duration trials (MD ‐3.11; 95% CI ‐8.62 to 2.41), and there was no increase in symptoms in any of these trials.

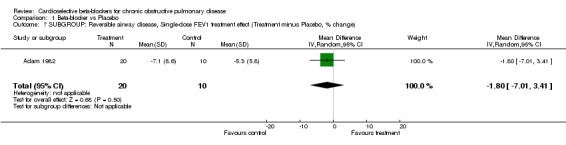

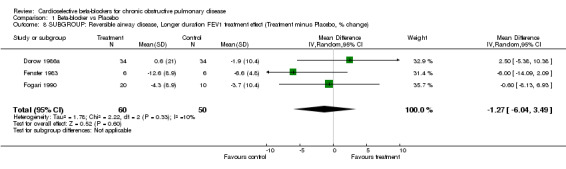

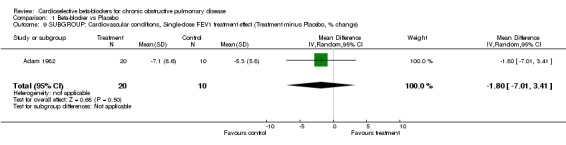

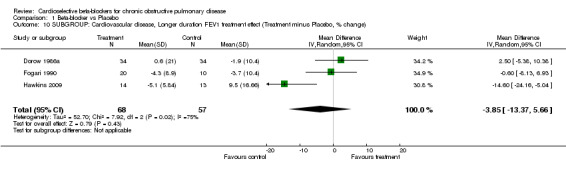

Another subgroup analysed patients who had COPD with a reversible component, as demonstrated by an improvement in FEV1 of at least 15% after beta2‐agonists (Adam 1982; Dorow 1986a; Dorow 1986b; Fenster 1983; Fogari 1990; Macquin‐Mavier 1988; von Wichert 1982). When these seven trials were analysed separately, there still was no significant change in FEV1 seen in single‐dose trials (MD ‐1.80; 95% CI ‐7.01 to 3.41) or those of longer duration (MD ‐1.27; 95% CI ‐6.04 to 3.49), and no increase in symptoms were found in any study.

In eight of the trials, all participants had comorbid cardiovascular conditions such as hypertension, angina or heart failure (Adam 1982; Anderson 1980; Hawkins 2009; Macquin‐Mavier 1988; Perks 1978; Tivenius 1976; von Wichert 1982; Wunderlich 1980). When only these trials were included in the analysis, there was no significant FEV1 treatment effect seen for single‐dose studies (MD ‐1.80; 95% CI ‐7.01 to 3.41) or for those of longer duration (MD ‐3.85; 95% CI ‐13.37 to 5.66). No respiratory symptoms were seen in the treatment group in any of the studies.

Sensitivity Analyses:

A sensitivity analysis was performed to evaluate the effect on FEV1 of including studies that did not provide placebo controls (McGavin 1978; Sorbini 1982). When only placebo‐controlled trials were included in the analysis for single‐dose treatment (Adam 1982; Sinclair 1979) there was no significant change in any of the results, with less than 1% absolute difference in FEV1 treatment effect. All seven of the longer‐duration trials of FEV1 provided placebo controls, although 2 of these did not provide data on the baseline FEV1 prior to placebo administration (Dorow 1986a; Fogari 1990). When these trials were excluded, there was less than 2% absolute change in FEV1 treatment effect (MD ‐4.00%; 95%CI ‐8.09 to 0.08).

Another sensitivity analysis evaluated the effect of including trials that did not provide study SDs for the FEV1 treatment effect (Fenster 1983; Fogari 1990; Ranchod 1982; McGavin 1978; Sinclair 1979). Excluding trials that did not provide SD data did not significantly effect the results for single‐dose trials (MD ‐3.01%; 95%CI ‐7.12 to 1.09), or for those of longer duration (MD 2.48%; 95%CI ‐8.11 to 3.14). Another analysis was performed by replacing the pooled SD with the lowest and highest available SD. For the single‐dose trials and longer duration trials, the difference in results between the highest and lowest SD was not significantly different, with an absolute change in FEV1 of less than 1%.

Discussion

Summary:

This meta‐analysis pooled 22 randomised, blinded controlled trials on the use of cardioselective beta‐blockers in patients with COPD. These trials demonstrated that cardioselective beta‐blockers, given as a single dose or for longer durations, produced no significant change in FEV1 or respiratory symptoms compared to placebo, and did not effect the FEV1 treatment response to beta2‐agonists. These findings were unchanged in subgroup analyses of COPD patients with FEV1 < 1.4 litres or < 50 % normal predicted values, or for those with a reversible obstructive component (FEV1 increase of > 15% to beta2‐agonists). In addition, beta‐blockers were found to be well tolerated in trials that evaluated patients with comorbid cardiovascular conditions such as hypertension, angina and heart failure. The findings of this analysis are supported by the results of another meta‐analysis that demonstrated that cardioselective beta‐blockers given to patients with reversible airway disease did not produce clinically significant adverse respiratory effects (Salpeter 2002).

In one of the 22 trials, beta‐blocker treatment resulted in a small reduction in FEV1 compared with placebo, without affecting respiratory symptoms or bronchodilator response (Hawkins 2009). In this trial, a four‐month course of bisoprolol in patients with moderate to severe COPD and concomitant symptomatic heart failure was associated with a non‐significant trend towards improved quality of life and functional status compared with placebo. Another trial reported a reduction in peak flow rate for beta‐blocker treatment compared with placebo, but did not provide sufficient FEV1 data to be included in the analysis (Butland 1983). In this trial, atenolol and metoprolol treatment in patients with severe COPD (FEV1 < 30% normal predicted values) increased exercise tolerance due to a reduction in heart rate, oxygen consumption, and minute ventilation, without affecting respiratory symptoms. None of the other trials in the analysis found a treatment effect on FEV1, respiratory symptoms or bronchodilator response. This indicates that small reductions in airflow that may be seen with cardioselective beta‐blockers do not pose clinical problems. In fact, treatment still results in improvements in exercise tolerance and functional status, as has been consistently shown with beta‐blocker treatment in cardiac disease (Abdulla 2006; Hulsmann 2001; Poulsen 2000).

Limitations of the Review:

This meta‐analysis has several limitations, some that are similar to those found with most meta‐analyses (Ionnidis 1999). The analysis only reports on published literature and is therefore subject to publication bias. Most of the studies were small and 80% of the participants were men. The randomisation process was not well delineated in many of the studies and some were single‐blinded rather than double‐blinded. A few studies did not have placebo controls, and many did not provide individual study standard deviations for FEV1 treatment effects. However, sensitivity analyses were performed to evaluate the effect of including these trials and the results were found to be consistent throughout, due to the relatively homogeneous nature of the individual trial results.

Generalisability and Applicability of Results:

This current meta‐analysis indicates that the use of cardioselective beta‐blockers is safe in patients who have COPD, with or without a reversible component. Treatment was also found to be safe for a subgroup of patients with concomitant angina, ischemic heart disease, congestive heart failure or hypertension. These findings are consistent with other studies that have investigated the use of beta‐blockers in patients with COPD and concomitant hypertension or cardiac disease and have found that these medicines were well tolerated, without any worsening of respiratory symptoms or FEV1 (Camsari 2003; Chen 2001; Falliers 1985; Formgren 1976; George 1983; Jabbour 2010; Krauss 1984; Mooss 1994; Quan 1983). Observational studies have evaluated beta‐blocker use in patients with COPD and concomitant cardiac disease and have showed a significant reduction in total mortality for those treated with beta‐blockers compared to those who were not (Au 2004; Gottlieb 1998; Van Gestel 2008). Other studies have shown that beta‐blocker use in patients with COPD are associated with a significant reduction in COPD exacerbations and COPD deaths (Dransfield 2008; Rutten 2010), possibly as a result of improved myocardial and ventilatory efficiency.

The standard of care in the 1980s and 1990s was to avoid the use of beta‐blockers in patients with reactive or obstructive airway disease (Belli 1995; JNC 1997; O'Malley 1991; Tattersfield 1986; Tattersfield 1990). This reluctance to use beta‐blockers was based on case reports of acute bronchospasm in patients with reversible airway disease precipitated by high doses of non‐cardioselective beta‐blockers (Anderson 1979; McNeill 1964; Raine 1981; Zaid 1966). Only a small fraction of patients with heart disease who would benefit from beta‐blockers were being given this treatment (Krumholz 1998; Sial 1994; Soumerai 1997; Wang 1998). A study by Heller and colleagues published in 2000 showed that COPD and asthma were the comorbidities most commonly associated with beta‐blockers being withheld in elderly patients after a myocardial infarction (Heller 2000). More recently, evidence of the safety of beta‐blockers in obstructive airways disease has been accumulating, but still there is significant underutilization of beta‐blockers in patients with concomitant COPD and cardiac disease (Egred 2005).

Cardioselective beta‐blockers such as atenolol, bisoprolol and metoprolol are at least 20 times more potent at blocking beta‐1 receptors than beta‐2 receptors (Wellstein 1987). The studies in this meta‐analysis gave doses of beta‐blockers ranging from therapeutic to supra‐therapeutic doses, those that are not generally used for initiation of treatment. For example, subjects were given single doses of metoprolol or atenolol ranging from 50 to 200 mg, without a clinically apparent effect on respiratory function.

The cardioselective beta‐blockers used in this trial included those with and without intrinsic sympathomimetic activity. In the single‐dose trials that measured FEV1 treatment effect, only beta1‐blockers without intrinsic sympathomimetic activity were studied, so these could not be compared to those with sympathomimetic activity. In the longer duration trials, when cardioselective beta‐blockers with intrinsic sympathomimetic activity (acebutolol and celiprolol) were compared to those without activity (atenolol and metoprolol), there was no significant change in FEV1 treatment effect. Of note, the cardiovascular benefits seen with beta‐blockers appear to be lost when intrinsic sympathomimetic activity is present (Wadworth 1991).

Due to the proven mortality benefit of beta‐blockers in numerous conditions, many of the other relative or absolute contraindications traditionally listed for beta‐blockers have been questioned and disproved, including impaired left ventricular function, peripheral vascular disease, diabetes mellitus, depression, and advanced age (Beto 1992; Bright 1992; Gottlieb 1998; Jonas 1996; Kjekshus 1990; Krumholz 1999; Lechat 1998; Opie 1990; Radack 1991; Rosenson 1993; Wicklmayr 1990). This meta‐analysis suggests that cardioselective beta‐blockers can safely be given to patients with COPD, even for those with a reversible component or with severe baseline obstruction. It is clear from this evidence that the proven benefit of cardioselective beta‐blocker treatment far outweighs the risks in these patients, as found in the studies identified in this review.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Beta‐blocker treatment reduces mortality in patients with cardiovascular disease. The available data from controlled trials indicate that cardioselective beta‐blocker use in patients with COPD has no significant adverse effects on FEV1, respiratory symptoms or response to beta2‐agonists, even for those with severe chronic airways obstruction.

Implications for research.

From the accumulated evidence we have now, it is apparent that patients with COPD should not be excluded from future beta‐blocker trials so that the treatment effect can be studied in this substantial population.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 11 August 2016 | Amended | New study (Mainguy 2010) identified involving 27 participants. Has been added to Studies awaiting classification and will be incorporated in to a future update as it is believed it would not currently impact on conclusions significantly. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 2000 Review first published: Issue 2, 2001

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 11 October 2010 | New search has been performed | New literature search. Two new trials added (Hawkins 2009 and Chang 2010). |

| 4 July 2005 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Christopher Cates and Steve Milan for their guidance with this review, Emma Welsh and Toby Lasserson for their technical and editorial assistance, and Karen Blackhall and Liz Arnold for coordinating the trials search.

Appendices

Appendix 1. CENTRAL database search strategy for COPD

#1 MeSH descriptor Lung Diseases, Obstructive, this term only #2 MeSH descriptor Pulmonary Disease, Chronic Obstructive explode all trees #3 (emphysema*) #4 (chronic* near/3 bronchiti*) #5 (obstruct*) near/3 (pulmonary or lung* or airway* or airflow* or bronch* or respirat*) #6 (COPD) #7 (COAD) #8 (COBD) #9 (AECB) #10 (#1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9)

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Beta‐blocker vs Placebo.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Beta‐blocker vs Placebo, Outcome 1 Single‐dose FEV1 treatment effect (Treatment minus Placebo, % change from baseline).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Beta‐blocker vs Placebo, Outcome 2 Single‐dose respiratory symptoms (Participants with symptoms, Treatment minus Placebo).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Beta‐blocker vs Placebo, Outcome 3 Longer duration FEV1 treatment effect (Treatment minus Placebo, % change from baseline).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Beta‐blocker vs Placebo, Outcome 4 Longer duration respiratory symptoms (Participants with symptoms, Treatment minus Placebo).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Beta‐blocker vs Placebo, Outcome 5 SUBGROUP: Severe COPD, Single‐dose FEV1 treatment effect (Treatment minus Placebo, % change).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Beta‐blocker vs Placebo, Outcome 6 SUBGROUP: Severe COPD, Longer duration FEV1 treatment effect (Treatment minus Placebo, % change).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Beta‐blocker vs Placebo, Outcome 7 SUBGROUP: Reversible airway disease, Single‐dose FEV1 treatment effect (Treatment minus Placebo, % change).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Beta‐blocker vs Placebo, Outcome 8 SUBGROUP: Reversible airway disease, Longer duration FEV1 treatment effect (Treatment minus Placebo, % change).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Beta‐blocker vs Placebo, Outcome 9 SUBGROUP: Cardiovascular conditions, Single‐dose FEV1 treatment effect (Treatment minus Placebo, % change).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Beta‐blocker vs Placebo, Outcome 10 SUBGROUP: Cardiovascular disease, Longer duration FEV1 treatment effect (Treatment minus Placebo, % change).

Comparison 2. Beta‐blocker + agonist vs Placebo + agonist.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Single‐dose Beta‐agonist treatment effect (Treatment‐agonist effect minus Placebo‐agonist effect, % change) | 2 | 50 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.21 [‐10.97, 8.56] |

| 2 Longer duration Beta‐agonist treatment effect (Treatment‐agonist effect minus Placebo‐agonist effect,% change) | 3 | 89 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.70 [‐5.02, 3.63] |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Beta‐blocker + agonist vs Placebo + agonist, Outcome 1 Single‐dose Beta‐agonist treatment effect (Treatment‐agonist effect minus Placebo‐agonist effect, % change).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Beta‐blocker + agonist vs Placebo + agonist, Outcome 2 Longer duration Beta‐agonist treatment effect (Treatment‐agonist effect minus Placebo‐agonist effect,% change).

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Adam 1982.

| Methods | Trial design: Double‐blind, placebo‐controlled cross‐over. | |

| Participants | Country: Australia. Setting: clinic. Treatment N: 20 Placebo N: 10 Age: 65.1. Sex: unclear. Inclusion: Hypertension with COPD on clinical grounds. | |

| Interventions | Treatment: Single‐dose metoprolol 100mg PO, atenolol 100mg. Comparison: placebo | |

| Outcomes | Outcomes: FEV1 3.5 hours after drug, symptoms | |

| Notes | Nonselectives studied: labetalol, propranolol | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Anderson 1980.

| Methods | Trial design: Double‐blind, placebo‐controlled cross‐over | |

| Participants | Country: Wales. Setting: clinic. Treatment N: 9 Placebo N: 9. Age: 59. Sex: unclear. Inclusion: Hypertension or angina with chronic bronchitis, PEFR < 70% predicted | |

| Interventions | Treatment: Single‐dose metoprolol 100 mg PO, Comparison: placebo | |

| Outcomes | Outcomes: peak flows measured from 15 to 180 minutes after drug, and symptoms | |

| Notes | Nonselective studied: propranolol | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

Beil 1977.

| Methods | Trial design: Double‐blind, placebo‐controlled cross‐over | |

| Participants | Country: Germany. Setting: clinic. Treatment N: 44. Placebo N: 22. Age: 26‐75. Sex: 82% males. Inclusion: chronic obstructive disease on clinical grounds, in remission phase | |

| Interventions | Treatment: Single‐dose atenolol 100mg, Comparison: placebo | |

| Outcomes | Outcomes: Airway resistance, thoracic gas volume, pulse, blood pressure, and symptoms | |

| Notes | Nonselective studied: propranolol | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Butland 1983.

| Methods | Trial design: Double‐blind placebo‐controlled cross‐over | |

| Participants | Country: United Kingdom. Setting: hospital. Treatment N: 24. Placebo N: 12. Age: 61. Sex: 83% male. Inclusion: Emphysema with severe airway obstruction, FEV1 <1 L. | |

| Interventions | Treatment: 4 weeks duration metoprolol 100mg/day PO, atenolol 100mg/day. Comparison: 4 weeks placebo. Single dose study not placebo controlled, excluded from symptom analysis | |

| Outcomes | Outcomes: FEV1 measured with exercise, excluded from analysis. Symptoms | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Chang 2010.

| Methods | Trial design: Double‐blind placebo‐controlled cross‐over | |

| Participants | Country: New Zealand. Setting: outpatient. Treatment N: 11. Placebo N: 11. Age: 65. Sex: 83% male. Inclusion: Moderate COPD | |

| Interventions | Treatment: 7‐10 days metoprolol 95 mg/day, and open‐label metoprolol 190 mg/day Comparison: 7‐10 days placebo |

|

| Outcomes | FEV1, exercise capacity, salbutamol response curve | |

| Notes | Nonselective studied: propranolol | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Dorow 1986a.

| Methods | Trial design: Single‐blind + double‐blind placebo‐controlled cross‐over | |

| Participants | Country: Germany. Setting: University clinic. Treatment N: 34. Placebo N: 34. Age: unclear. Sex: unclear. Inclusion: Hypertension with reversible bronchial obstruction, FEV1 40‐70% predicted, with > 15% increase with beta‐agonist | |

| Interventions | Treatment: 12 weeks celiprolol 200‐600 mg/day PO. Comparison: 4 weeks placebo | |

| Outcomes | Outcomes: FEV1 measured at baseline, 4 weeks, 8 weeks. Note: Baseline FEV1 not recorded prior to placebo. Symptoms measured as change in number from baseline of incidents and days observed, so excluded from analysis | |

| Notes | Other comparison studied: chlorthalidone | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

Dorow 1986b.

| Methods | Trial design: Double‐blind, placebo‐controlled cross‐over | |

| Participants | Country: Germany. Setting: University clinic. Treatment N: 24. Placebo N: 12. Age: 46. Sex: 92% male. Inclusion: COPD clinically stable with reversible component, FEV1 > 15% increase with beta‐agonist, and angina | |

| Interventions | Treatment: Single‐dose bisoprolol 20 mg PO, atenolol 100mg. Comparison: placebo | |

| Outcomes | Airway resistance, blood pressure, pulse. FEV1 reported in graph form, excluded from analysis. Symptoms. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Fenster 1983.

| Methods | Trial design: Single‐blind placebo‐controlled cross‐over | |

| Participants | Country: USA. Setting: Pulmonary clinic. Treatment N: 6. Placebo N: 6. Age: 48.6. Sex: 33% male. Inclusion: COPD with FEV1 < 60% predicted, reversible with > 15% increase with beta‐agonist. | |

| Interventions | Treatment: 1 week metoprolol, 200 mg/day PO. Comparison: 1 week placebo | |

| Outcomes | Outcomes: FEV1 at baseline, day 2, 5. Symptoms | |

| Notes | No FEV1 standard deviations recorded. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

Fogari 1990.

| Methods | Trial design: Single‐blind, placebo‐controlled cross‐over | |

| Participants | Country: Italy. Settling: University clinic.Treatment N: 20. Placebo N: 10. Age: 57. Sex: 100% male. Inclusion: Hypertension, and reversible COPD with FEV1 < 70%, >15% increase with beta‐agonist | |

| Interventions | Treatment: 1 week atenolol 100 mg/day PO, celiprolol 200 mg/day. Comparison: 2 weeks placebo | |

| Outcomes | Outcomes: FEV1 measured at baseline and 1 week, symptoms. Note: Baseline FEV1 not recorded prior to placebo. | |

| Notes | Nonselective studied: oxprenolol, propranolol. No FEV1 standard deviations recorded. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

Hawkins 2009.

| Methods | Trial design: double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial | |

| Participants | Country: United Kingdom. Settling: Outpatient.Treatment N: 14. Placebo N: 13. Age: 70.7. Sex: 70% male. Inclusion:Stable symptomatic congestive heart failure and moderate to severe COPD | |

| Interventions | Treatment: 4 months duration bisoprolol, dose titrated to tolerance Comparison: 4 months duration placebo |

|

| Outcomes | FEV1, FEV1 response to salbutamol. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Lammers 1985a.

| Methods | Trial design: Single‐blind + double‐blind placebo‐controlled cross‐over | |

| Participants | Country: Netherlands. Setting: outpatient clinic. Treatment N: 8. Placebo N: 8. Age: 52.7+/‐ 0.4. Sex: 88% male. Inclusion: Hypertension and COPD according to ATS guidelines. | |

| Interventions | Treatment: 4 weeks metoprolol 100mg BID PO. Comparison: 4 weeks placebo | |

| Outcomes | FEV1 measured in graph form at baseline, 2, 4 weeks, excluded from analysis. Symptoms | |

| Notes | Nonselective studied: pindolol | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

Macquin‐Mavier 1988.

| Methods | Trial design: Double‐blind, placebo‐controlled cross‐over | |

| Participants | Country: France. Setting: laboratory. Treatment N: 18. Placebo N: 9. Age: 38. Sex: 55% male. Inclusion: Smokers with chronic reversible airway obstruction, with FEV1 < 70% predicted, > 20% increase with beta‐agonist. | |

| Interventions | Treatment: Single‐dose bisoprolol 10 mg PO, acebutolol 100 mg. Comparison: placebo. | |

| Outcomes | Specific airway conductance at baseline and each week. Symptoms | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

McGavin 1978.

| Methods | Trial design: Double‐blind cross‐over with baseline controls. No placebo | |

| Participants | Country: United Kingdom. Setting: Hospital. Treatment N: 9. Placebo N: 0. Inclusion: Chronic airways obstruction with breathlessness, average FEV1 40% predicted. Response to propranolol excluded. | |

| Interventions | Treatment: Single dose metoprolol 100 mg PO. Comparison: propranolol (excluded) | |

| Outcomes | Outcomes: FEV1 measured at baseline, 1, 6 hours after drug. Symptoms excluded, because no placebo. | |

| Notes | Nonselective studied: propranolol. No FEV1 standard deviations recorded. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Perks 1978.

| Methods | Trial design: Double‐blind, placebo‐controlled cross‐over | |

| Participants | Country: United Kingdom. Setting:hospital. Treatment N: 20. Placebo N: 10. Age: 56.5, Sex: 80% male. Inclusion: Angina or hypertension with chronic airways obstruction on clinical grounds, some reversible. | |

| Interventions | Treatment: Single‐dose atenolol 50 + 100 mg PO, Comparison: placebo | |

| Outcomes | FEV1 measurement in graph form at baseline, 15 minutes, then every hour for 3 hours, excluded from analysis. Symptoms | |

| Notes | Nonselective studied: oxprenolol | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Ranchod 1982.

| Methods | Trial design: Double‐blind placebo‐controlled cross‐over | |

| Participants | Country: South Africa. Setting: University clinic. Treatment N: 15. Placebo N: 15. Age: 39. Sex: unclear. Inclusion: Cigarette smokers with chronic bronchitis on clinical grounds with mild airflow obstruction, no reversibility. | |

| Interventions | Treatment: 1 week atenolol 100 mg/day PO. Comparison: placebo | |

| Outcomes | FEV1 at baseline, 120 minutes, 7 days, symptoms | |

| Notes | Nonselective studied: propranolol. No FEV1 standard deviations recorded. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Schanning 1976.

| Methods | Trial design: Double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, cross‐over | |

| Participants | Country: Norway. Setting: unclear. Treatment N: 20. Placebo N: 20. Age: 53.0. Sex: 85% male. Inclusion: Chronic obstructive lung disease on clinical grounds, stable phase. | |

| Interventions | Treatment: Single‐dose practolol 15 mg IV, Comparison: placebo IV | |

| Outcomes | Outcomes: FEV1 measured at baseline and during 10 and 15 minutes of exercise, excluded from analysis. Symptoms | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Sinclair 1979.

| Methods | Trial design: Double‐blind, placebo‐controlled cross‐over | |

| Participants | Country: Scottland. Setting: laboratory. Treatment N: 10. Placebo N: 10. Age: 63. Sex: unclear. Inclusion: Chronic bronchitis, FEV1 < 70% predicted | |

| Interventions | Treatment: Single‐dose Metoprolol 0.12mg/kg IV. Comparison: placebo IV. | |

| Outcomes | Outcomes: FEV1 measured at baseline, every 15 minutes for 1 hour, symptoms | |

| Notes | Nonselective studied: propranolol. No FEV1 standard deviations recorded. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Sorbini 1982.

| Methods | Trial design: Double‐blind cross‐over with baseline controls. No placebo | |

| Participants | Country: Italy. Setting: unclear. Treatment N: 32. Placebo N: 0. Inclusion: Chronic obstructive lung disease or asthma on clinical grounds, with long history of attacks, now in remission phase. | |

| Interventions | Treatment: Single‐dose metoprolol 50mg PO, 100mg, 150mg, 200 mg. Comparison: none | |

| Outcomes | Outcomes: FEV1, forced vital capacity, pulse, airway resistance, peak flow at baseline, every hour for 3 hours, 6 hours. Symptoms excluded because no placebo | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Tivenius 1976.

| Methods | Trial design: Double‐blind placebo‐controlled cross‐over | |

| Participants | Country: Sweden. Setting: lung clinic. Treatment N: 12. Placebo N: 12. Age: 53. Sex: 92% male. Inclusion: COPD on clinical grounds, recovering from acute exacerbation. | |

| Interventions | Treatment: 2 days metoprolol 50 mg TID PO, Comparison: placebo | |

| Outcomes | Outcomes: FEV1, forced vital capacity, pulse, blood pressure measured at 2 hours and 2 days, reported without baseline, excluded from analysis. Symptoms | |

| Notes | Nonselective studied: propranolol | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

van der Woude 2005.

| Methods | Trial design: Double‐blind, placebo‐controlled cross‐over | |

| Participants | Country: Netherlands Setting: Single center Treatment N: 15 Placebo N: 15 | |

| Interventions | Treatment: 4 days metoprolol 100 mg PO BID and celiprolol 200 mg PO BID. Comparison: 4 days Placebo | |

| Outcomes | Outcomes: FEV1 baseline, after treatment and 30 minutes after formoterol, and PC20 | |

| Notes | Nonselective studied: propranolol | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

von Wichert 1982.

| Methods | Trial design: Double‐blind, placebo‐controlled cross‐over | |

| Participants | Country: Germany. Setting: University clinic. Treatment N: 12. Placebo N: 12. Age: 45‐55. Sex: 83% male. Inclusion: Reversiblle chronic airways obstruction with chronic bronchitis according to WHO, >15% with beta‐agonist, positive acetylcholine test. | |

| Interventions | Treatment: Single‐dose metoprolol 100 mg PO. Comparison: placebo | |

| Outcomes | Outcomes: Total airway resistance measured at baseline, 90 minutes, after beta‐agonist. Symptoms | |

| Notes | Nonselective studied: pinpolol | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Wunderlich 1980.

| Methods | Trial design: Double‐blind placebo‐controlled cross‐over | |

| Participants | Country: Germany. Settting: clinic. Treatment N: 35. Placebo N: 35. Age: 61.9. Sex: 69% male. Inclusion: Hypertension or ischemic heart disease and COPD, on clinical grounds. | |

| Interventions | Treatment: 2 days metoprolol 100mg BID PO. Comparison: 2 days placebo | |

| Outcomes | Outcomes: FEV1, forced residual capacity, airway resistance, pulse, blood pressure measured at baseline and every day for 2 days, measured in graph form so excluded from analysis. Symptoms | |

| Notes | Nonselective studied: propranolol | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Abraham 1981 | Not randomized |

| Addis 1976 | No cardioselective blocker |

| Anavekar 1982 | No cardioselective blocker |

| Camsari 2003 | Not blinded |

| Chester 1981 | No cardioselective blocker |

| Clague 1984 | No FEV1 data or placebo‐controls |

| Dal Negro 1981 | Not blinded |

| Dal Negro 1986 | Not blinded |

| Dorow 1984 | Not blinded |

| Dorow 1986c | Not blinded |

| George 1983 | No cardioselective blocker |

| Jabbour 2010 | No placebo, and no baseline FEV1 off beta‐blocker |

| Johnsson 1976 | Review |

| Lois 1997 | Review |

| Lois 1999 | Review |

| Meier 1966a | No cardioselective blocker |

| Meier 1966b | Duplicate of 1986a |

| Nordstrom 1975 | No cardioselective blocker |

| Quan 1983 | Not randomized |

| Ulmer 1976 | No cardioselective blocker |

| van Herwaarden 1983 | Review |

| Wettengel 1970 | No cardioselective blocker |

Characteristics of studies awaiting assessment [ordered by study ID]

Mainguy 2010.

| Methods | Randomized, double‐blinded, cross‐over study |

| Participants | 27 participants with moderate to severe COPD |

| Interventions | Bisoprolol or placebo given for 2 weeks |

| Outcomes | mean baseline FEV1 is 1.4 L |

| Notes | Qualify for subgroup analysis of severe COPD due to mean baseline FEV1 being 1.4 L |

Contributions of authors

Shelley Salpeter: Developed review protocol, search strategy, trial selection, data extraction and analysis, and manuscript preparation. For the addition of two trials in the 2010 update; data extraction and analysis, statistical management, manuscript preparation and management of Revman protocol.

Thomas Ormistion: Search strategy, trial selection, data extraction, manuscript preparation.

Edwin Salpeter: Prof. Salpeter died November 2008, prior to the preparation of the 2010 update.

His contributions from 2001 ‐ 2005 were: Development of review protocol, data analysis, statistical management, manuscript preparation, for the 2002 review and the 2005 update.

Sources of support

Internal sources

Santa Clara Valley Medical Center, USA.

External sources

Garfield Weston Foundation, UK.

Declarations of interest

None

Edited (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Adam 1982 {published data only}

- Adam WR, Meagher EJ, Barter CE. Labetalol, beta blockers, and acute deterioration of chronic airway obstruction. Clinical and experimental hypertension. Part A, Theory and Practice 1982;4(8):1419‐28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Anderson 1980 {published data only}

- Anderson G, Jariwalla AG, Al‐Zaibak M. A comparison of oral metoprolol and propranolol in patients with chronic bronchitis. The Journal of International Medical Research 1980;8(2):136‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Beil 1977 {published data only}

- Beil M, Ulmer WT. Effects of a new cardioselective beta‐adrenergic blocker (atenolol) on airway resistance in chronic obstructive disease [Wirkung eines neuen kardioselektiven Betablockers (Atenolol) auf den Stromungswiderstand bei chronisch obstruktiven Atemwegserkrankungen]. Arzneimittel‐Forschung 1977;27(1):419‐22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Butland 1983 {published data only}

- Butland RJ, Pang JA, Geddes DM. Effect of beta‐adrenergic blockade on hyperventilation and exercise tolerance in emphysema. Journal of Applied Physiology 1983;54(5):1368‐73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Chang 2010 {published data only}

- Change CL, Mills GD, McLachlan JD, Karalus NC, Hancox RJ. Cardio‐selective and non‐selective beta‐blockers in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: effects on bronchodilator response and exercise. Internal Medicine Journal 2010;40:193‐200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dorow 1986a {published data only}

- Dorow P, Clauzel AM, Capone P, Mayol R, Mathieu M. A comparison of celiprolol and chlorthalidone in hypertensive patients with reversible bronchial obstruction. Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology 1986;8(Suppl 4):S102‐S4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dorow 1986b {published data only}

- Dorow P, Bethge H, Tonnesmann U. Effects of single oral doses of bisoprolol and atenolol on airway function in nonasthmatic chronic obstructive lung disease and angina pectoris. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 1986;31(2):143‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Fenster 1983 {published data only}

- Fenster PE, Hasan FM, Abraham T, Woolfenden J. Effect of metoprolol on cardiac and pulmonary function in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Clinical Cardiology 1983;6(3):125‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Fogari 1990 {published data only}

- Fogari R, Zoppi A, Tettamanti F, Poletti L, Rizzardi G, Fiocchi G. Comparative effects of celiprolol, propranolol, oxprenolol, and atenolol on respiratory function in hypertensive patients with chronic obstructive lung disease. Cardiovascular Drugs and Therapy 1990;4(4):1145‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hawkins 2009 {published data only}

- Hawkins NM, MacDonald MR, Petrie MC, Chalmers GW, Carter R, Dunn FG, McMurray JJV. Bisoprolol in patients with heart failure and moderate to severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized controlled trial. European Journal of Heart Failure 2009;11:684‐690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lammers 1985a {published data only}

- Lammers JW, Folgerin HT, Herwaarden CL. Ventilatory effects of long‐term treatment with pindolol and metoprolol in hypertensive patients with chronic obstructive lung disease. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 1985;20(3):205‐10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Macquin‐Mavier 1988 {published data only}

- Macquin‐Mavier I, Roudot‐Thoraval F, Clerici C, George C, Harf A. Comparative effects of bisoprolol and acebutolol in smokers with airway obstruction. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 1988;26(3):279‐84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

McGavin 1978 {published data only}

- McGavin CR, Williams IP. The effects of oral propranolol and metoprolol on lung function and exercise performance in chronic airways obstruction. British Journal of Diseases of the Chest 1978;72:327‐32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Perks 1978 {published data only}

- Perks WH, Chatterjee SS, Croxson RS, Cruilshank JM. Comparison of atenolol and oxprenolol in patients with angina or hypertension and co‐existent chronic airways obstruction. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 1978;5:101‐6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ranchod 1982 {published data only}

- Ranchod A, Keeton GR, Benatar SR. The effect of beta‐blockers on ventilatory function in chronic bronchitis. South African Medical Journal 1982;61(12):423‐4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schanning 1976 {published data only}

- Schanning J, Vilsvik JS. Beta1‐blocker (Practolol) and exercise in patients with chronic obstructive lung disease. Acta Medica Scandinavica 1976;199:61‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sinclair 1979 {published data only}

- Sinclair DJ. Comparison of effects of propranolol and metoprolol on airways obstruction in chronic bronchitis. British Medical Journal 1979;1(6157):168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sorbini 1982 {published data only}

- Sorbini CA, Grassi V, Tantucci C, Todisco T, Motolese M, Verdecchia P. Acute effects of oral metoptolol on ventilatory function in patients with chronic obstructive lung disease. Acta Therapeutica 1982;8:5‐16. [Google Scholar]

Tivenius 1976 {published data only}

- Tivenius L. Effects of multiple doses of metoprolol and propranolol on ventilatory function in patients with chronic obstructive lung disease. Scandinavian Journal of Respiratory Diseases 1976;57(4):190‐6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

van der Woude 2005 {published data only}

- Woude HJ, Zaagsma J, Postmas DS, Winter TH, Julst M, Aalbers R. Detrimental effects of beta‐blockers in COPD. A concern for nonselective beta‐blockers. Chest 2005;127(3):818‐24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

von Wichert 1982 {published data only}

- Wichert P. Reversibility of bronchospasm in airway obstruction. American Heart Journal 1982;104:446‐50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wunderlich 1980 {published data only}

- Wunderlich J, Macha HN, Wudicke H, Huckauf H. Beta‐adrenoceptor blockers and terbutaline in patients with chronic obstructive lung disease. Effects and interaction after oral administration. Chest 1980;78(5):714‐20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Abraham 1981 {published data only}

- Abraham TA, Hasan FM, Fenster PE, Marcus FI. Effect of intravenous metoprolol on reversible obstructive airways disease. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics 1981;29(5):582‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Addis 1976 {published data only}

- Addis GJ, Thorp JM. Effects of oxprenolol on the airways of normal and bronchitic subjects. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 1976;9:259‐63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Anavekar 1982 {published data only}

- Anavekar SN, Barter C, Adam WR, Doyle AE. A double‐blind comparison of verapamil and labetalol in hypertensive patients with coexisting chronic obstructive airways disease. Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology 1982;4(Suppl):S374‐7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Camsari 2003 {published data only}

- Camsari A, Arikan S, Avan C, Kaya D, Pekdemir H, Cicek D, Kiykim A, Sezer K, Akkus N, Alkan M, Aydogu S. Metoprolol, a beta‐1 selective blocker, can be used safely in corornary artery disease patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Heart Vessels 2003;18:188‐192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Chester 1981 {published data only}

- Chester EH, Schwartz HJ, Fleming GM. Adverse effect of propranolol on airway function in nonasthmatic chronic obstructive lung disease. Chest 1981;79:540‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Clague 1984 {published data only}

- Clague HW, Ahmad D, Carruthers SG. Influence of cardioselectivity and respiratory disease on pulmonary responsiveness to beta‐blockade. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 1984;27(5):517‐23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dal Negro 1981 {published data only}

- Dal Negro R, Turco R. Changes in alveolar ventilation distribution due to beta antagonists induced by four different drugs in patients with chronic obstructive lung disease. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, Therapy and Toxicology 1981;19:234‐5. [Google Scholar]

Dal Negro 1986 {published data only}

- Dal Negro RW, Zoccatelli O, Pomari C, Trevisan F, Turco P. Respiratory effects of four adrenergic blocking agents combined with a diuretic in treating hypertension with concurrent chronic obstructive lung disease. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacology Research 1986;6(4):283‐9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dorow 1984 {published data only}

- Dorow P, Tonnesmann U. Dose‐response relationship of the beta‐adrenoceptor antagonist bisoprolol in patients with coronary heart disease and chronic obstructive bronchitis. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 1984;27:135‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dorow 1986c {published data only}

- Dorow P, Schiess W. Bopindolol, pindolol, and atenolol in patients with chronic obstructive lung disease. Klinische Wochenschrift 1986;64(8):366‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

George 1983 {published data only}

- George RB, Manocha K, Burford JG, Conrad SA, Kinasewitz GT. Effects of labetalol in hypertensive patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chest 1983;83(3):457‐60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jabbour 2010 {published data only}

- Jabbour A, Macdonald PS, Keough AM, Kotlyar E, Mellenkjaer S, Coleman CF, Elsik M, Krum H, Hayward CS. Differences between beta‐blockers in patients with chronic heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2010;44:1780‐1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Johnsson 1976 {published data only}

- Johnsson G. Use of beta‐adrenergic blockers in combination with beta‐stimulators in patients with obstructive lung disease. Drugs 1976;11(Suppl 1):171‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lois 1997 {published data only}

- Lois M, Honig E. Beta‐blockade post‐MI: safe for patients with asthma or COPD?. The Journal of Respiratory Diseases 1997;18(6):568‐91. [Google Scholar]

Lois 1999 {published data only}

- Lois M, Roman J, Honig E. Using beta‐blockers for CHF in patients with COPD. The Journal of Respiratory Diseases 1999;20(1):31‐43. [Google Scholar]

Meier 1966a {published data only}

- Meier VJ, Lydtin H, Zollner N. [On the effect of adrenergic beta‐receptor‐blocking agents on the ventilatory function in obstructive lung diseases]. Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift 1966;91(4):145‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Meier 1966b {published data only}

- Meier J, Lydtin H, Zollner N. The action of adrenergic beta‐receptor blockers on ventilatory functions in obstructive lung diseases. German Medical Monthly 1966;11(1):1‐3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Nordstrom 1975 {published data only}

- Nordstrom LA, MacDonals F, Gobel FL. Effect of propranolol on respiratory function and exercise tolerance in patients with chronic obstructive lung disease. Chest 1975;67(3):287‐92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Quan 1983 {published data only}

- Quan SF, Fenster PE, Hanson CD, Coaker LA, Basista MP. Suppression of atrial ectopy with intravenous metoprolol in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients. Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 1983;23(8‐9):341‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ulmer 1976 {published data only}

- Ulmer I, Lanser K. Propranolol and Pindolol in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [Propranolol und Pindolol bei chronisch‐obstruktiver Atemwegserkrankung.]. Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift 1976;101(48):1765‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

van Herwaarden 1983 {published data only}

- Herwaarden CL. Beta‐adrenocepptor blockade and pulmonary function in patients suffering from chronic obstructive lung disease. Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology 1983;5(Suppl 1):S46‐50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wettengel 1970 {published data only}

- Wettengel R, Fabel H. Effect of different beta‐receptor blocking agents on ventilation in obstructive respiratory tract disease. Comparative studies [Wirkung verschiedener beta‐Rezeptoren‐Blocker auf die Ventilation bei. Vergleichenden Untersuchungen]. Deutsch Medizinische Wochenschrift 1970;95(36):1816‐21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies awaiting assessment

Mainguy 2010 {published data only}

- Mainguy V, Girard D, Saey D, Milot J, Maltais F, Provencher S. Effects of cardioselective beta‐blockers on dynamic hyperinflation and on exercise tolerance in moderate‐to‐severe copd [Abstract]. Canadian Respiratory Journal [Revue canadienne de pneumologie] 2010;8(2):e27. [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Abdulla 2006

- Abdulla J, Kober L, Christensen E, Torp‐Pedersen C. Effect of beta‐blocker therapy on functional status in patients with heart failure ‐ a meta‐analysis. European Journal of Heart Failure 2006;8(5):522‐31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Anderson 1979

- Anderson EG, Calcraft B, Jariwalla AG, Al‐Zaibak M. Persistent asthma after treatment with beta‐blocking agents. British Journal of Diseases of the Chest 1979;73(4):407‐8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

ATS 1995

- American Thoracic Society. Standards for the diagnosis and care of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. American Thoracic Society. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 1995;152(5 Pt 2):S77‐121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Au 2004

- Au DH, Bryson CL, Fan US, Udris EM, Curtis JR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD. Beta‐blockers as single‐agent therapy for hypertension and the risk fo mortality among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. American Journal of Medicine 2004;117:925‐931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Beattie 2008

- Beattie WS, Wijeysundera DN, Karkouti K, McCluskey S, Tait G. Does tight heart rate control improve beta‐blocker efficacy? An updated analysis of the noncardiac surgical randomized trials. Cardiovascular Anesthesiology 2008;106:1039‐1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Belli 1995

- Belli G, Topol EJ. Adjunctive pharmacologic strategies for acute MI. Contemporary Internal Medicine 1995;7(8):51‐9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Beto 1992

- Beto JA, Bansal VK. Quality of life in treatment of hypertension: A meta‐analysis of clinical trials. American Journal of Hypertension 1992;5(3):125‐33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bright 1992

- Bright J, Everitt DE. Beta‐blockers and depression: Evidence against an assoication. JAMA 1992;267(13):1783‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Chafin 1999

- Chafin CC, Soberman JE, Demirkan K, Self T. Beta‐blockers after myocardial infarction: Do benefits ever outweigh risks in asthma?. Cardiology 1999;92:99‐105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Chen 2001

- Chen J, Radford MJ, Wang Y, Marciniak TA, Krumholz HM. Effectiveness of beta‐blocker therapy after acute myocardial infarction in elderly patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or asthma. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2001;37:1950‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Craig 1996

- Craig T, Richerson HB, Moeckli J. Problem drugs for the patient with asthma. Comprehensive Therapy 1996;22(6):339‐44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

DerSimonian 1986

- DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta‐analysis in clinical trials. Controlled Clinical Trials 1986;7:177‐88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Doughty 1997

- Doughty RN, Rodgers A, Sharpe N, MacMahon S. Effects of beta‐blocker therapy on mortality in patients with heart failure. European Heart Journal 1997;18(4):560‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dransfield 2008

- Dransfield MT, Rowe SM, Johnson JE, Bailey WC, Gerald LB. Use of beta‐blockers and the risk of death in hospitalized patients with acute exacerbations of COPD. Thorax 2008;63:301‐305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Egred 2005

- Egred M, Shaw M, Mohammad B, Waitt P, Rodrigues E. Under‐use of beta‐blockers in patients with ischemic heart disease and comcomitant chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. QJM 2005;7:493‐397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Falliers 1985

- Falliers CJ, Vrchota J, Blasucci DJ, Maloy JW, Medakovic M. The effects of treatments with labetalol and hydrochlorothiazide on ventilatory function of asthmatic hypertensive patients with demonstrated bronchosensitivity to propranolol. Journal of Clinical Hypertension 1985;1(1):70‐9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Fitzgerald 1991

- Fitzgerald J. The applied pharmacology of beta‐adrenoceptor antagonist (beta‐blockers) in relation to clinical outcomes. Cardiovascular Drugs and Therapy 1991;5:561‐76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Formgren 1976

- Formgren H. The effect of metoprolol and practolol on lung function and blood pressure in hypertensive asthmatics. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 1976;3:1007‐14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Freemantle 1999

- Freemantle N, Cleland J, Young P, Mason J, Harrison J. Beta blockade after myocardial infarction: systematic review and meta regression analysis. BMJ 1999;318:1730‐7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gottlieb 1998

- Gottlieb SS, McCarter RJ, Vogel RA. Effect of beta‐blockade on mortality among high‐risk and low‐risk patients after myocardial infarction. New England Journal of Medicine 1998;339(8):489‐97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Heidenreich 1999

- Heidenreich PA, McDonald KM, Hastie T, Fadel B, Lee BK, Hlatky MA. Meta‐analysis of trials comparing beta‐blockers, calcium antagonists, and nitrates for stable angina. JAMA 1999;281(20):1927‐36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Heller 2000

- Heller DA, Ahern FM, Kozak M. Changes in rates of beta‐blocker use between 1994 and 1997 among elderly survivors of acute myocardial infarcion. American Heart Journal 2000;140:663‐71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hulsmann 2001

- Hulsmann M, Sturm B, Pacher R, Berger R, Bojic A, Frey B, Stanek B. Long‐term effect of atenolol on ejection fraction, symptoms, and exercise variables in patients with advanced left ventricular dysfunction. Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation 2001;20(11):1174‐80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ionnidis 1999

- Ionnidis JP, Lau J. Pooling research results: benefits and limitations of meta‐analysis. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality Improvement 1999;25(9):462‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

IPPSH 1985

- The IPPPSH Collaborative Group. Cardiovascular risk and risk factors in a randonized trial of treatment based on the beta‐blocker oxprenolo: The Internation Prospective Primary Prevention Study in Hypertension (IPPPSH). Journal of Hypertension 1985;3:379‐92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

JNC 1997

- JNC VI. The sixth report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Archives of Internal Medicine 1997;157:2413‐46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jonas 1996

- Jonas M, Reicher‐Reiss H, Boyko V, Shotan A, Mandelzweig L, Goldbourt U, et al. Usefulness of beta‐blocker therapy in patients with non‐insulin‐dependent diabetes mellitus and coronary artery disease. American Journal of Cardiology 1996;77:1273‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jones 1980

- Jones M, John R, Jones G. The effect of oxprenolol, acebutolol and propranolol on thyroid hormones in hyperthyroid subjects. Clinical Endocrinology 1980;13:343‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kendall 1997

- Kendall MJ. Clinical relevance of pharmacokinetic differences between beta blockers. American Journal of Cardiology 1997;80(9B):15J‐9J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kennedy 1995

- Kennedy HL, Rosenson RS. Physician use of beta‐adrenergic blocking therapy: A changing perspective. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 1995;26(2):547‐52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kjekshus 1990

- Kjekshus J, Gilpin E, Cali G, Blackey AR, Henning H, Ross J. Diabetic patients and beta‐blockers after acute myocardial infarction. European Heart Journal 1990;11:43‐50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Klein 1994

- Klein I, Becker DV, Levey GS. Treatment of hyperthyroid disease. Annals of Internal Medicine 1994;121(3):281‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Koch‐Weser 1984

- Koch‐Weser J. Beta‐adrenergic blockade for survivors of acute myocardial infarction. New England Journal of Medicine 1984;310:830‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Krauss 1984