To the Editor:

Since March 2020, nephrologists have faced challenges owing to COVID-19: in dialysis delivery, higher rates of acute kidney injury, and increased mortality in patients with concomitant COVID-19 and kidney dysfunction.1 The impact of the pandemic on European nephrology residents’ emotional well-being and learning of theoretical knowledge and practical skills was not studied. This binational survey was created in May 2021 by the young Belgian and French nephrologists’ association (Club des Jeunes Néphrologues [Supplementary Figure S1]). Methods are detailed in the Supplementary Methods.S1

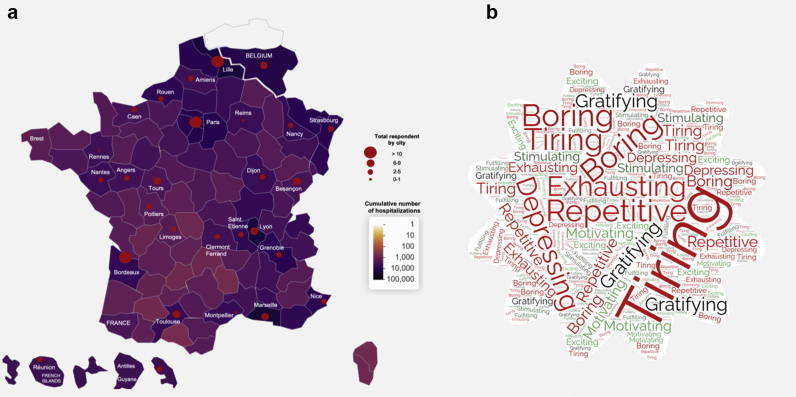

Our study included 133 nephrology residents: 125 from France and 8 from French-speaking Belgium. Participation was homogeneous on the territory and proportional to the cumulative hospitalization rate for COVID-19 (Figure 1a).

Figure 1.

(a) Correlation between the number of participants in the survey and the cumulative number of hospitalizations for COVID-19. The colored areas reveal the cumulative number of hospitalizations from March 15, 2020, to May 1, 2021, by territorial department (France: national data SIVIC data.gouv.fr & Laboratoire Icube CHRU Strasbourg, Dr. Fabacher et al./Belgium: national federal institute “Sciensano”), and the diameter of red dots is proportional to the number of participants. (b) Adjectives used by residents to characterize their work. Specific words used by residents to characterize the time-period, using the online software www.nuagedemots.fr revealing in visual form the frequency of the words used.

Survey results are presented in Table 1. Of the respondents, 75.9% considered their theoretical training negatively affected. Concerning learnings, kidney biopsy was the most affected procedure (36.1% of unsatisfied participants), 66.2% of the residents felt that they had acquired new knowledge outside nephrology, and 66.9% had improved capacity in palliative care.

Table 1.

Survey results

| Respondent information | |

| Nephrology residents | N = 133 |

| Age | 27 ± 2 |

| Country of origin | |

| France | 125 (94.0) |

| Belgium | 8 (6.0) |

| Sex, male | 70 (53.6) |

| Validated residency semesters (6 mo) | 5 ± 2 |

| Practical training | |

| Assignment | |

| COVID-19 medicine department | 69 (51.9) |

| Non–COVID-19 medicine department | 105 (78.9) |

| COVID-19 intensive care unit | 68 (51.1) |

| Non–COVID-19 intensive care unit | 29 (21.8) |

| Other | 11 (8.3) |

| % of time spent in COVID-19 unit | 16.7 ± 28.9 |

| Teaching of invasive procedures impacted: | |

| Venous catheter placement | 23 (17.3) |

| Arterial catheter placement | 22 (16.5) |

| Kidney biopsy | 48 (36.1) |

| Salivary gland biopsy | 29 (21.8) |

| Pleural puncture | 26 (19.5) |

| Ascites puncture | 30 (22.6) |

| Lumbar puncture | 29 (21.8) |

| Better communication with: | |

| Medical teams | 48 (36.1) |

| Paramedical teams | 54 (40.6) |

| Other specialists | 55 (41.4) |

| Patients | 52 (39.1) |

| Patients’ families | 58 (43.6) |

| Better management of palliative support | 89 (66.9) |

| Responsibilities | |

| Much less | 5 (3.8) |

| Rather less | 3 (2.3) |

| Same | 79 (59.4) |

| Rather more | 37 (27.8) |

| Much more | 9 (6.8) |

| Less bedside teaching | 64 (48.1) |

| Theoretical training | |

| Local theoretical formation negatively impacted | 106 (79.7) |

| Regional or national theoretical formation negatively impacted | 101 (75.9) |

| Online resources sufficient for training | |

| Not at all | 43 (32.3) |

| A little | 73 (54.9) |

| A lot | 15 (11.3) |

| Extremely | 2 (1.5) |

| Missing face-to-face format | |

| Not at all | 8 (6.0) |

| A little | 39 (29.3) |

| A lot | 54 (40.6) |

| Extremely | 32 (24.1) |

| Aspects of teaching impacted by videoconference format | |

| Interactivity | 96 (72.1) |

| Exchanges with the teacher | 80 (60.1) |

| Dynamism | 79 (59.4) |

| Ability to focus | 95 (71.4) |

| Regular bibliographic research about COVID-19 | 31 (23.3) |

| Less nephrology | 74 (55.6) |

| Acquisitions of new knowledge (other than nephrology) | 88 (66.2) |

| Mental health | |

| Happiness at work | |

| Not at all | 11 (8.3) |

| A little | 55 (41.3) |

| A lot | 64 (48.1) |

| Extremely | 3 (2.3) |

| Estimated weekly work hours | 61.5 ± 8.8 |

| Words that best describe the past year | |

| Repetitive | 99 (74.4) |

| Boring | 43 (32.3) |

| Depressing | 36 (27.1) |

| Tiring | 69 (51.9) |

| Exhausting | 37 (27.7) |

| Gratifying | 25 (18.8) |

| Stimulating | 17 (12.8) |

| Motivating | 19 (14.3) |

| Fulfilling | 4 (3.0) |

| Exciting | 6 (4.5) |

| Negative impact on the moral | |

| Not at all | 9 (6.7) |

| A little | 31 (23.3) |

| A lot | 57 (42.9) |

| Extremely | 36 (27.1) |

| Negative impact on the efficiency at work | |

| Not at all | 36 (27.1) |

| A little | 65 (48.9) |

| A lot | 25 (18.8) |

| Extremely | 7 (5.3) |

| Worrying about its own health | |

| Not at all | 72 (54.1) |

| A little | 53 (39.8) |

| A lot | 8 (6.0) |

| Extremely | 0 (0.0) |

| Worrying about the health of its relatives | |

| Not at all | 15 (11.3) |

| A little | 64 (47.4) |

| A lot | 49 (36.8) |

| Extremely | 6 (4.5) |

| Support from colleagues | 113 (85.0) |

| Support from relatives | 120 (90.2) |

The questions were organized in the following 4 categories: respondent information, theoretical training, practical training, and mental health (descriptive statistics).

Concerning well-being, there was a significant negative impact on global morale (42.9%; Figure 1b) and work efficiency (48.9%), but with preserved happiness at work. The residents were rather worried on the health of their relatives (88.7%) than their own (43.8%). They were mostly able to find support from their colleagues and relatives.

Overall, French-speaking nephrology residents were heavily involved in the management of the COVID-19 crisis, because of their transversality, frequent implication in other specialties (notably intensive care unit), and long cursus,2 with a significant impact on their mental health, theoretical learning, and practical knowledge of nephrology.

American nephrology fellows perceived less impact on their education,3 but adaptation to online teaching technologies seemed better than in our study. Furthermore, 42% reported an alteration of their quality of life and 33% a poorer work-life balance.3

In a recent previous study, only 34.4% of French residents considered the teaching of kidney biopsy to have been sufficient during their residency,4 and it therefore seems to worsen with the crisis.

This study alerts to the negative impact of the pandemic on the training of nephrology residents. Despite a significant increase in the physician’s workload,S2 maintaining quality training for their young colleagues must remain a priority.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the residents who responded to the survey. The authors warmly thank Rouba Kaedbey, a PhD student in architecture and urban planning, for the help concerning the map.

Author Contributions

Design: VM, MB, ASG, CL, and AH.

Recruitment: VM, ASG, CL, AB, AH, and MB.

Data analysis: VM and MB.

Writing (first draft): VM.

Writing (editing): ASG, CL, AB, AH, and MB.

Supervision: MB.

All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Figure S1. Club des Jeunes Néphrologues.

Supplementary Methods.

Supplementary References.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Club des Jeunes Néphrologues.

Supplementary Methods.

Supplementary Reference.

STROBE Statement (PDF).

References

- 1.Bruchfeld A. The COVID-19 pandemic: consequences for nephrology. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2021;17:81–82. doi: 10.1038/s41581-020-00381-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lohéac C., Maisons V., Bureau C., Bertocchio J.P. Amending of the 3rd cycle of medical studies in France: what the nephrologists stand for. Article in French. Nephrol Ther. 2020;16:50–58. doi: 10.1016/j.nephro.2019.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pivert K.A., Boyle S.M., Halbach S.M., et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on nephrology fellow training and well-being in the United States: a national survey. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;32:1236–1248. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2020111636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bobot M., Maisons V., Chopinet S., et al. National survey of invasive procedural training for nephrology fellows and residents in France: from bedside mentoring to simulation-based teaching. Clin Kidney J. 2021;14:445–447. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfaa111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Club des Jeunes Néphrologues.