Significance

The motor cortex (MCX) and corticospinal tract are necessary for producing skilled movements. Whereas much is known about MCX plasticity and its role in acquiring and maintaining motor skills, much less is known about spinal circuit contributions. We investigate a spinal locus for corticospinal tract plasticity in anesthetized rats. We identify long-term potentiation (LTP) of the corticospinal tract monosynaptic excitatory synapse with spinal interneurons, as well as LTP of an oligosynaptic response in the wrist motor pool. Our findings are important for understanding the key structures for motor learning and motor recovery after injury and suggest that spinal circuits, which implement supraspinal control signals for muscle contraction, are capable of further modifying MCX actions in an activity-dependent manner.

Keywords: long-term potentiation, spinal cord, cortiospinal tract, theta burst stimulation, local field potentials

Abstract

Although it is well known that activity-dependent motor cortex (MCX) plasticity produces long-term potentiation (LTP) of local cortical circuits, leading to enhanced muscle function, the effects on the corticospinal projection to spinal neurons has not yet been thoroughly studied. Here, we investigate a spinal locus for corticospinal tract (CST) plasticity in anesthetized rats using multichannel recording of motor-evoked, intraspinal local field potentials (LFPs) at the sixth cervical spinal cord segment. We produced LTP by intermittent theta burst electrical stimulation (iTBS) of the wrist area of MCX. Approximately 3 min of MCX iTBS potentiated the monosynaptic excitatory LFP recorded within the CST termination field in the dorsal horn and intermediate zone for at least 15 min after stimulation. Ventrolaterally, in the spinal cord gray matter, which is outside the CST termination field in rats, iTBS potentiated an oligosynaptic negative LFP that was localized to the wrist muscle motor pool. Spinal LTP remained robust, despite pharmacological blockade of iTBS-induced LTP within MCX using MK801, showing that activity-dependent spinal plasticity can be induced without concurrent MCX LTP. Pyramidal tract iTBS, which preferentially activates the CST, also produced significant spinal LTP, indicating the capacity for plasticity at the CST–spinal interneuron synapse. Our findings show CST monosynaptic LTP in spinal interneurons and demonstrate that spinal premotor circuits are capable of further modifying descending MCX control signals in an activity-dependent manner.

Many studies of motor system plasticity have focused on the motor cortex (MCX), in part, because the cortical motor representation is modified extensively during development and maturity as motor skills are acquired (1, 2). Activity-dependent long-term modification of the efficacy of synaptic transmission in the MCX, such as long-term potentiation (LTP) produced by repetitive electrical stimulation (3–5), has received extensive investigation at the cellular and molecular levels and as a possible mediator of learning and maintaining motor skills (6). Local MCX synaptic responses can be enhanced after intermittent theta burst stimulation (iTBS) (4, 7), a high-frequency stimulation protocol that is known to produce LTP in many cortical regions (e.g., refs. 4 and 8). Using repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) to implement TBS in healthy human subjects, Huang et al. (4) demonstrated a persistent increase in MCX excitability after the stimulation stopped. rTMS and electrical iTBS produce similar effects in the rat, showing consistency across species (9–11).

However, that a muscle-evoked potential (MEP) is larger after a period of MCX iTBS provides no distinction between changes produced by local MCX circuits or to plasticity at other levels of the corticospinal motor circuit (12), especially distally at the corticospinal tract (CST)–spinal neuron synapse. Stimulation and skill-learning studies in animals and humans have revealed expansion of the MCX representation of the stimulated site (13, 14), but this too does not distinguish local from distant changes. Whereas much is known about MCX reorganization and local cortical synaptic changes underlying corticospinal system plasticity, less is known about the contribution of spinal motor circuits. The necessity for the corticospinal system in H-reflex modulation (15, 16) and the capacity for spike timing–dependent plasticity for enhancement of corticomotoneuronal responses (17) point to a spinal locus. Knowledge of a spinal locus for corticospinal system plasticity is necessary for understanding the key structures for motor learning and targets for neuromodulation to promote motor recovery after injury. It is important to know if spinal circuits, which implement supraspinal control signals for muscle contractions, may themselves modify the actions of the MCX.

In this study, we investigate a spinal locus for corticospinal system plasticity in anesthetized rats. The goal of this study is to determine whether there is LTP-like plasticity in the spinal cord after MCX iTBS and, in particular, at the level of CST synapses with spinal interneurons. In their seminal study, Asanuma and colleagues showed that MCX tetanic stimulation, which produced cortical LTP, potentiated spinal interneuronal postsynaptic responses (18). In a limited number of intracellular spinal interneuron recording, they showed posttetanic potentiation and, in some interneurons, LTP, in response to the tetanizing stimulus. This suggests that corticospinal system plasticity induced in cortex can potentiate its most distal synapses in the spinal cord, but many questions remain.

We used an approach to assess spinal plasticity by recording local field potentials (LFPs) simultaneously from 32 sites within the spinal gray matter in the same transverse plane. We combine high-resolution spatial recordings with experimental manipulations to dissect the contributions of local MCX circuits and the CST to spinal LTP. In this way, we capture the segmental representation of MCX and CST action before and after inducing LTP in the corticospinal system. We show LTP of both the mono- and oligosynaptic MCX responses after MCX iTBS. Spinal activation maps revealed “plasticity hotspots” in the region of dense CST terminations within the gray matter and outside this CST projection zone in the wrist motor pool. Our findings reveal LTP between the CST and spinal neurons across an extensive, segmental territory. This demonstrates that spinal motor circuits are capable of augmenting the plasticity of descending cortical signals in an activity-dependent manner for muscle-response production.

Results

Experimental Design.

In anesthetized rats, we recorded intraspinal LFPs using a 32-channel electrode array (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 A and B) in response to a three-pulse, supraspinal stimulus probe. The three-pulse stimulus probe did not, by itself, produce LTP (SI Appendix, Fig. S2B). Moreover, the LTP that we report below is not dependent on use of the three-stimulus probe, since we also observed comparable LTP using a single-stimulus probe (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). We stimulated either the wrist area of MCX or the pyramidal tract (PT) in the caudal medulla. MCX stimulation activates the CST as well as other cortical efferent pathways, including the indirect spinal projections (corticorubrospinal and corticoreticulospinal tracts). PT stimulation is more selective for the CST. Stimulus-evoked responses were recorded concurrently in the extensor carpi radialis (ECR) muscle to validate the association between spinal and muscle responses. To identify the location of recording sites in proximity to wrist motoneurons, we retrogradely labeled ECR motoneurons (see Fig. 1C). Evoked spinal responses were stable across a given experiment (SI Appendix, Fig. S2A) with LFPs showing minimal amplitude differences over a typical 20-min experiment. During this period, the animals anesthetic state remained stable. We first present results describing the basic topography of the evoked MCX responses, which establishes the baseline activation map of MCX responses in the cervical enlargement. This forms the basis for examining and interpreting LFP changes following MCX iTBS, after MK801, and with PT iTBS.

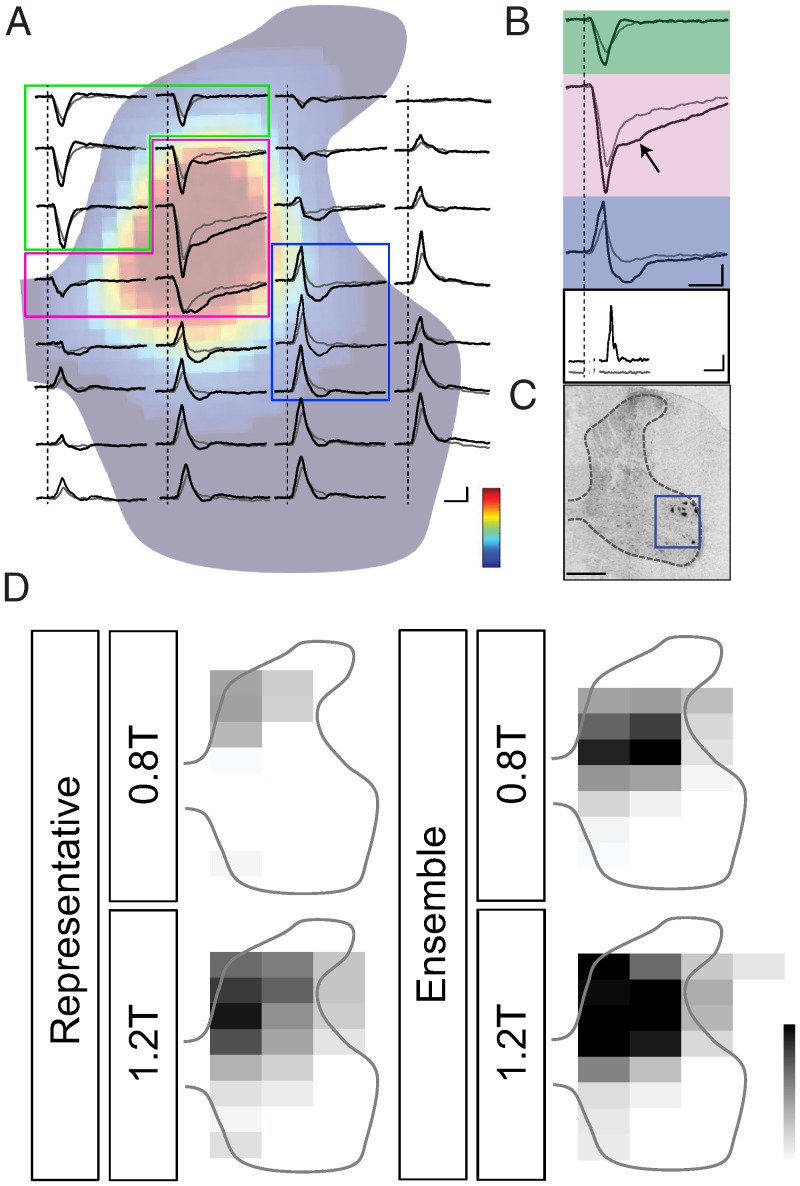

Fig. 1.

MCX-evoked spinal potentials in C6. (A) Recordings of averaged LFPs (n = 20 trials for each; probe stimulus, three pules with an interstimulus interval of 3.33 ms) at 0.8T (gray lines) and 1.2T (black lines) in one representative experiment. Tracers are overlaid on a heatmap of contralateral CST terminals in C6. Color scale: 0 to max (arbitrary units). Green, yellow, and blue show boundaries for the three regions of the spinal gray matter analyzed and shown in subsequent figures. The regions correspond to the dorsomedial dorsal horn and central zone of the dorsal horn and intermediate zone, which receive direct CST projections and display monosynaptic responses, and the region of the dorsolateral motor pool, which is outside the CST projection zone, and display an oligosynaptic response. (B). Enlargement of representative LFPs from each region (Top three; color coded) and concurrently recorded average ECR EMG (Bottom; gray, 0.8T and black, 1.2T). The vertical dotted line marks the onset of the probe stimulus (0 ms). Arrow in middle panel indicates a persistent negativity. Vertical dashed lines in A and B mark the onset of the MCX stimulus. Calibrations are the following: 100 µV, 10 ms (A); LFPs 200 µV, 10 ms (B); and EMG, 2 mV, 10 ms. (C) ECR motor neurons retrogradely labeled with CTB (rectangle). (Scale Bar, 0.5 mm.) Calibrations are the following: 100 µV, 20 ms (A); LFPs 200 µV, 20 ms (B); and EMG, 2 mV, 20 ms. (D) Grayscale heatmaps of integrated, raw LFP-negative voltages for 0.8T (Top) and 1.2T (Bottom) for representative (Left) and averaged (Right) responses of (n = 10) experiments. Gray scale calibrations are the following: 0 to max (−0.012 for representative and −0.005 for ensemble).

MCX Stimulation Evokes Mono- and Oligosynaptic Responses throughout the Cervical Gray Matter.

We first determined the topographic pattern of spinal cord responses following an MCX electrical stimulus (three pulses, interstimulus interval [ISI] = 3.3 ms) that was below threshold (T) for evoking an ECR MEP (0.8T; mean thresholds listed in SI Appendix, Table S3) and how this pattern changed when the stimulus intensity was increased to produce an electromyographic (EMG) response (1.2T). The initially negative (i.e., excitatory) monosynaptic field potentials (Fig. 1 A and B, green and magenta regions of interest [ROIs]) were recorded throughout wide areas of the dorsal horn and intermediate zone at 0.8T (laminae III to VI; Fig. 1A, gray traces). In this representative animal, there was a progressive reduction in the size of the initially negative response, with more ventral recording sites along a given electrode shank (medial and central electrode shanks; Fig. 1A). The distribution of the initially negative responses correspond to the distribution of CST cervical terminations (Fig. 1A, heatmap), which are densest centrally and medially in the dorsal horn and upper intermediate zone (corresponding to green- and magenta-colored sites; Fig. 1A). This field corresponds to the monosynaptic CST response recorded in other studies with PT stimulation (19). We also recorded this field with PT stimulation (see Fig. 4).

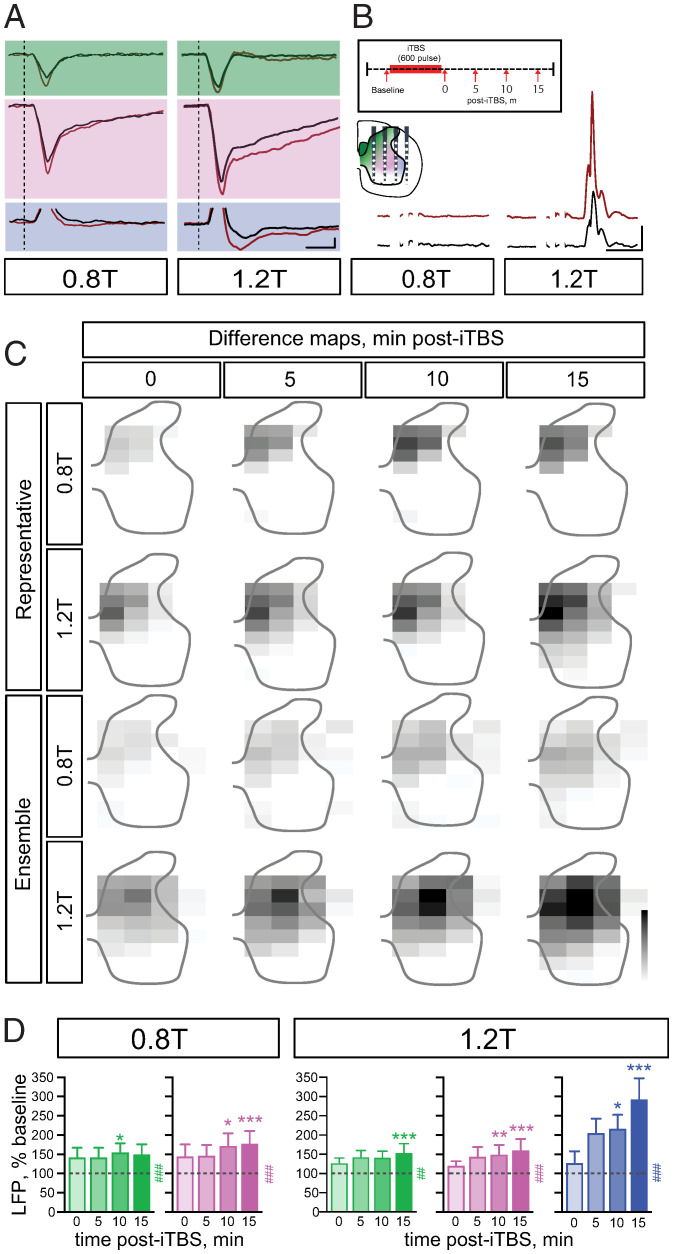

Fig. 4.

Intraspinal LFP potentiation in response to iTBS in medullary pyramid. (A) Representative example of concentric electrode track (diI) terminating in the medullary pyramid (PT). Dotted lines show the dorsal borders of the PT. (Scale Bar, 0.5 mm.) (B) Averaged intraspinal recordings (n = 20 stimulus repetitions) from the dorsomedial dorsal horn (green), central zone (magenta), and motor pool (blue) regions. (Top Inset) Recording schematic in relation to the three zones of interest. (Bottom Inset) EMG at baseline (black) and 15 min after iTBS. The dotted line represents the onset of the MCX probe stimulus (0 ms; three pulses, 3.33 ms ISI). Calibration is the following: LFP, 200 µV, 10 ms, EMG, 5 mV, 5 ms. (C) Difference activity heatmaps (i.e., between baseline pre-iTBS and post-iTBS at each time point) from a representative experiment (Top row) and average experiments (n = 5). Gray scale calibrations are the following: 0 to max, arbitrary units (−0.0025). (D) Integrated area of the negative LFPs as a percent of baseline for dorsomedial dorsal horn (green), central zone (magenta), and motor pool region (blue) ROIs at 1.2T (dotted line is at 100%; # indicates overall significance; and * indicates post hoc significance). LFP responses increased significantly in the dorsomedial dorsal horn (green) (Friedman statistic X2 = 9.75, P = 0.0302) at 10 min (131% ± 11.2, adjusted P = 0.02), in the central zone (magenta) (Friedman statistic X2 = 11.6, P = 0.0448) at 10 min (131.6% ± 10.7, adjusted P = 0.01) and 15 min (134% ± 10.34, adjusted P = 0.02), and in the motor pool region (blue) (Friedman statistic X2 = 11.52, P = 0.021) at 10 min (154.6% ± 36.46, adjusted P = 0.01) and 15 min (154.8% ± 28.99, adjusted P = 0.02). Error bars and values represent mean ± the SEM. Friedman test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons.

At the base of the dorsal horn and intermediate zone, the CST monosynaptic LFP inverted to an initially positive potential. The onset latency and time to peak of the positive response were the same as those of the initially negative responses. The most lateral electrode (No. 4) consistently showed a different pattern, with only initially positive responses that returned to baseline. The regions in which there was an initially positive response are largely devoid of CST termination in the rat. This initially positive response is the current source for the monosynaptic CST response (19–21).

The late negativity in the central parts of laminae IV to VII (Fig. 1B, magenta; see arrow) is within the densest CST termination field. This late response was always preceded by a very phasic, and typically large-amplitude, CST monosynaptic LFP. We refer to this late negativity within the CST termination field as an oligosynaptic excitatory synaptic response; however, it could be mediated by slow, inactivating ion channels associated with the glutamatergic monosynaptic CST response or slowly conducting CST monosynaptic response. Within the territory of the motor pools (Fig. 1 A and B, blue and Fig. 1C), at 0.8T, we observed only the positivity (monosynaptic response source) and its return to baseline.

In the same animal, at 1.2T (Fig. 1A, solid traces) the initially negative CST monosynaptic and later oligosynaptic excitatory responses increased in amplitude. Importantly, in the region of the dorsolateral motor pools, identified by the location of ECR motoneurons (Fig. 1C), recordings revealed the presence of a late negativity (Fig. 1 A and B, blue ROI). Based on several criteria—restricted anatomical localization, emergence at currents above wrist EMG threshold, presence with either MCX or PT stimulation (see Fig. 4C), and timing—we propose that this late negativity reflects di/oligosynaptic CST excitation of motoneurons. Medial to the dorsolateral motor pools in the intermediate zone, we also observed a late negativity that may reflect oligosynaptic interneuronal responses or motoneuronal responses from medially directed dendrites (22). Note that, in the dorsolateral motor pool region (23), the large and spatially diffused, initially positive response likely obscures the onset of the focal negativity (blue shading, ventral ROI). To summarize, phasic, monosynaptic, oligosynaptic, and late persistent responses have distinct localizations. The late motor pool response is only present at the suprathreshold current.

Segmental Representation of Muscle Recruitment.

The heat maps (Fig. 1D) plot integrated LFP-negative voltages from each electrode site in the array for the representative animal (A) and the ensemble (n = 10 rats). At 0.8T, the negative responses colocalize with the distribution of CST termination (Fig. 1A, heatmap and Fig. 1D and SI Appendix, Fig. S1). At 1.2T, the negative response territory both expands outside the CST termination field and becomes larger within the region of densest terminations. (Fig. 1D and Movie S1). Note that the dorsolateral ventral horn response is the late negativity in the region of wrist motoneurons [Fig. 1B (23)]. To summarize, MCX stimulation evoked monosynaptic excitatory responses within the CST termination field, with the largest responses localized to the region of densest terminations. Stimulation at a current that evoked an EMG response recruited an oligosynaptic response localized to the region of the dorsolateral motor pool.

MCX-Evoked Intraspinal Field Potentials Are Potentiated following iTBS.

We next examined the effects of iTBS on the MCX-evoked LFPs (Fig. 2A). Repeated testing to evoke responses using a triple-pulse stimulation protocol does not, by itself, lead to response potentiation (SI Appendix, Fig. S2B) and also is demonstrated in a prior study (24). EMG responses were qualitatively assessed for threshold and enhancement. iTBS produced MEP facilitation at all time points examined but only at the 1.2T current (Fig. 2B). The subthreshold stimulus did not evoke an MEP during the post-iTBS part of the experiment. LFP recordings from a representative animal (Fig. 2A, Top) reveal potentiation of the monosynaptic response at both 0.8T and 1.2T and the later oligosynaptic response, which potentiates more at the suprathreshold current. Spinal response enhancement was observed at all quantified time points, as well as at selected later time points (up to 30 min tested) but not quantified. Within the region of the dorsolateral motor pool (Fig. 2A, blue), we only observed potentiation of the late negative response at 1.2T. Moreover, potentiation was selective for the late negativity not the earlier positive current source. Thus, LFP enhancement in the region of the ECR motor pool is revealed only with the suprathreshold current, and this parallels EMG enhancement, which was only at 1.2T (Fig. 2B). iTBS did not bring the subthreshold spinal motor response above threshold, similar to human studies (e.g., refs. 25 and 26).

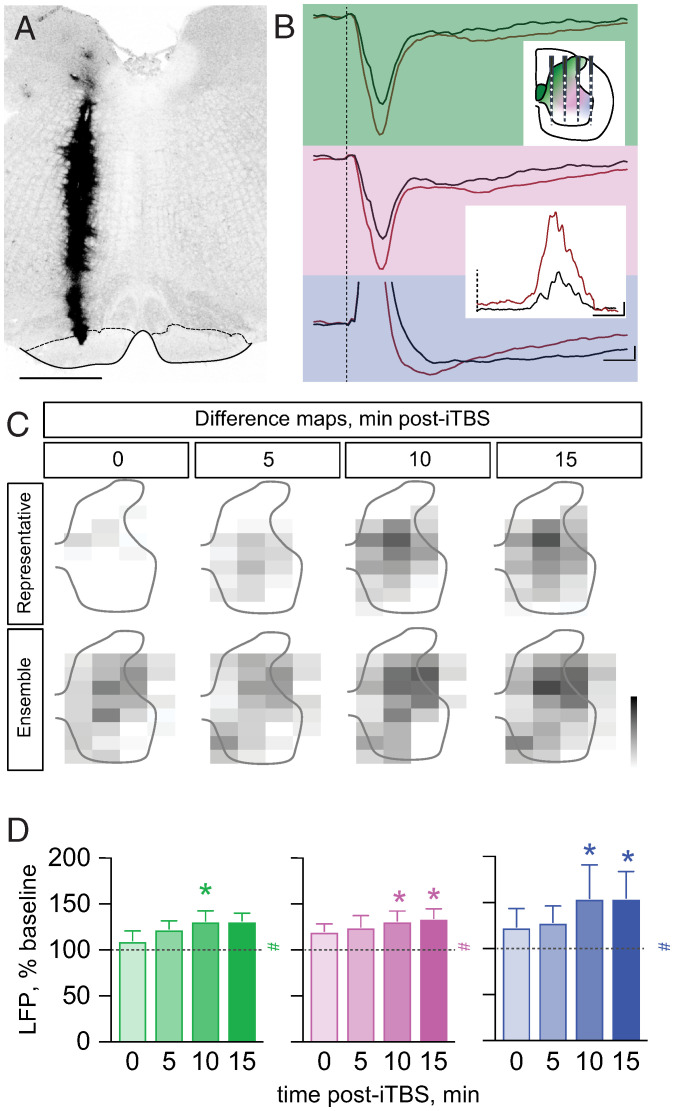

Fig. 2.

MCX iTBS-evoked spinal plasticity at C6. (A) Recordings of averaged LFPs (n = 20 trials for each; three pulses, 3.33 ms ISI) at baseline (black lines) and 15-min post-iTBS (red lines) from one representative experiment. Top traces (green) are from the dorsomedial dorsal horn, middle traces (magenta) from the central gray matter, and bottom traces (blue) from the motor pool region. (B) MEP potentiation after iTBS at 15-min poststimulation (baseline, black; 15 min, red). (Top Inset) Timeline for experiment (see Materials and Methods). (Bottom Inset) Schematic of electrode-recording array in relation to the three color-coded regions. Calibrations in A and B are the following: LFP, 200 µV, 20 ms; EMG, 2 mV, 10 ms. (C) Grayscale difference activity heatmaps (i.e., between baseline pre-iTBS and post-iTBS at each time point) at 0.8T (first and third rows) and 1.2T (second and fourth rows) in a representative experiment and average of all experiments (ensemble, n = 10 rats). Grayscale calibrations are the following: 0 to max, arbitrary units (representative, 0.8T; 0.005; 1.2T; −0.015 to 0 arbitrary units; ensemble −0.0025). (D) Integrated area of the negative LFPs as a percent of baseline for dorsomedial dorsal horn (green), central zone (magenta), and motor pool (blue) regions (Left, 0.8T; Right, 1.2T; dotted line is at 100%; # indicates overall significance; and * indicates post hoc significance). For 0.8T, LFP responses increased significantly in the dorsomedial dorsal horn (green) at 10 min (145.2% ± 23.88 adjusted P = 0.0436) and in the central zone (magenta) (Friedman statistic X2 = 28.97, P = 0.0003) at 10 min (172.8% ± 31.48, adjusted P = 0.0153) and at 15 min (178.5% ± 32.25, adjusted P = 0.001). For 1.2T, LFP responses increased significantly in the dorsomedial dorsal horn (green) (Friedman statistic X2 = 14.75, P = 0.0053) at 15 min (155% ± 22.43, adjusted P = 0.0007), in the central zone (magenta) (Friedman statistic X2 = 20.95 P < 0.0003) at 10 min (150% ± 24.17, adjusted P = 0.0059) and 15 min (161.6% ± 28.13, adjusted P < 0.0002), and in the motor pool region (blue) (X2 = 19.84, P < 0.0005) at 10 min (217% ± 35.73, adjusted P = 0.0187) and 15 min (293.7% ± 53.69, adjusted P = 0.0009). Error bars and values represent mean ± the SEM. Friedman test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons.

Spatial Representation of Potentiated Spinal Segmental Responses following iTBS.

To represent response potentiation development after iTBS, we constructed difference maps from the representative animal and the group (ensemble, n = 10) for each poststimulation recording time (Fig. 2C). Each recording location on the map plots the difference between baseline (pre-iTBS) LFP (as the integrated voltage negativity) and post-iTBS LFP for each time point. For the 0.8T stimulus, LFP enhancement was largely restricted to the CST termination region. At 1.2T, there was further enhancement in the dorsolateral motor pool region, as well as ventrally and medially in the ventral horn. We quantified response augmentation due to iTBS (Fig. 2D). Although there were effect size differences, significant LFP potentiation was observed for all three spinal ROIs (color coded; see Fig. 2B, spinal cord inset). Significant LFP enhancement of the early phase (onset to peak negativity) monosynaptic component also was observed (SI Appendix, Fig. S4A). Our findings show that MCX iTBS produces robust potentiation of both the monosynaptic and later oligosynaptic responses. Importantly, we also observed potentiation of the late negative field in the region of the dorsolateral motor pool.

MK801 Blocked Cortical but Not Spinal LTP.

MCX iTBS produces local LTP within MCX (27). To determine the extent to which spinal response enhancement depends on MCX LTP, we used the NMDA receptor antagonist MK801, locally applied to MCX, to attenuate or abrogate MCX LTP. We first confirmed that MCX iTBS produces potentiation of an evoked, local MCX field in our study (Fig. 3A). In the representative example, there was a 130% increase in peak-to-peak amplitude, similar to published reports (e.g., ref. 28) at 15-min post-iTBS. Across all experiments (n = 5), there was a 121% increase MCX LFP amplitude (Fig. 3B, artificial cerebral spinal fluid [ACSF]; gray bars). Local application of MK801, followed by a 30-min incubation period to penetrate the tissue, largely blocked MCX LFP potentiation in the representative example. LTP blockade was significant at 10- and 15-min post-iTBS. (Fig. 3B, black bars). ACSF had no effect on MCX LTP. We next determined the effect MK801 application had on spinal LTP induced by MCX iTBS. While abrogating cortical LTP, spinal LTP was reduced but remained significant and robust in all three ROIs. Cortical application of MK801 did not affect baseline LFP amplitude (SI Appendix, Fig. S5A) or integrated MEP responses (SI Appendix, Fig. S5B). The pharmacological blockade experiments suggest that a major site for plasticity after cortical iTBS is in the spinal cord and that spinal-level plasticity augments further LTP in MCX.

Fig. 3.

Intraspinal LFP potentiation after MCX iTBS is not blocked with MCX MK801 application. In all experiments, MK801 was administered and iTBS was applied 30 min later. Times shown are minutes post-iTBS. (A) iTBS produces local LFP potentiation (A, Top row), and local MK801 blocks this potentiation (A, Bottom row). Representative examples of MCX LFP potentiation with ACSF (Top row) and, for this example, partial blockade of the local MCX field potential potentiation with local application of MK801 (Bottom row). The gray shaded rectangles mark the sizes of the baseline MCX potential and the open rectangle, the potential measured 10 and 15 min after iTBS. Calibration is the following: 140 µV, 2 ms (Top), (Scale Bar, 63 µV, 2 ms) (Bottom). (B) Quantification of MCX LTP (n = 5 rats, ACSF; 6 rats, MK801 experiments), showing that iTBS produces local LTP (gray) and MK801 application prevents LTP (black; x2 = 13.66, P = 0.0034). Post hoc analysis of MK801 responses at 10 and 15 min are significantly less than with ACSF (adjusted P = 0.0225, 0.014, respectively) (Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparison). (C) Average intraspinal recordings of 20 frames in the dorsomedial dorsal horn (green), central zone (magenta), and motor pool region (blue). The dotted line represents the onset of probe stimulus (0 ms; three pulses, 3.33 ms ISI). Recordings at baseline (black) and 15 min (red) post-iTBS show poststimulation facilitation. (Inset) Concurrent EMG response at baseline and 15 min post-iTBS. Calibration is the following: LFP, 200 µV, 10 ms EMG, 5 mV, 5 ms. (D) Integrated area of the negative LFPs as a percent of baseline for dorsomedial dorsal horn (green), central zone (magenta), and motor pool region (blue) ROIs at 1.2T (dotted line is at 100%; # indicates overall significance; and * indicates post hoc significance). LFP responses increased significantly in the dorsomedial dorsal horn (green) (Friedman statistic X2 = 10.81, P = 0.028) at 15 min (134% ± 10, adjusted P = 0.0139), in the central zone (magenta) at 15 min (144.7% ± 26.02, adjusted P = 0.00352), and in the motor pool region (blue) (Friedman statistic X2 = 13.81, P = 0.079) at 15 min (185.9% ± 41.15, adjusted P = 0.0352). Error bars and values represent mean ± the SEM. Friedman test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons.

iTBS of PT Produces Spinal LTP.

Epidural electrical stimulation of MCX can activate multiple corticofugal projections, in particular, the direct corticospinal projection (i.e., the CST) and the indirect corticospinal projections, corticorubrospinal and corticoreticulospinal projections. Stimulation of the PT in the medulla primarily activates the CST projection, as the stimulation site is caudal to the red nucleus and most projections to the pontomedullary reticular formation. PT stimulation is commonly used as a way to preferentially activate the CST (e.g., ref. 19). MCX antidromic activation by PT stimulation did not produce LTP in MCX (18). We next determined if spinal LTP could still be achieved in the postsynaptic targets of the CST if we stimulate the PT directly using the same iTBS stimulation protocol used for MCX.

iTBS of the PT (Fig. 4A) produced MEP facilitation that persisted during the evaluation period (Fig. 4B, Inset), similar to what we observed following MCX iTBS and probing for LTP using three-pulse MCX stimulation. LFP recordings from a representative animal (Fig. 4B) showed potentiation, both in the dorsal horn and intermediate zone, as well as in the motor pool region. The difference maps (Fig. 4C) for the representative animal and ensemble (n = 5) show a similar pattern of dorsal monosynaptic negative responses, as we observed with MCX stimulation. Quantification revealed significant potentiation of the monosynaptic response in the dorsomedial, the central recording zone monosynaptic and oligosynaptic responses, and oligosynaptic dorsolateral motor pool region (Fig. 4D; mean threshold for PT experiments, 0.14 ± 0.01 mA). Similarly, significant LFP enhancement of the early monosynaptic component also was observed for PT stimulation (SI Appendix, Fig. S4B). Our findings show postsynaptic response potentiation at the level of the CST synapse with spinal interneurons, as well as oligosynaptic response potentiation.

Discussion

In contrast to the abundance of research on intrinsic plasticity in MCX (4, 25, 27), much less focus has been placed on whether the spinal neuronal response to CST activation can undergo plasticity. We delivered a brief bout of iTBS to MCX to produce corticospinal motor system plasticity LTP (4). MCX iTBS produced robust spinal LFP enhancement that remains after the blockade of MCX LTP. iTBS delivered to CST fibers in the PT also produced spinal LTP that was not different from the temporal pattern and spatial distribution of LTP produced by MCX iTBS but was smaller, which is likely due to the lack of an additive effect of local MCX LTP (see Spinal Representation of MCX- and PT-Induced LTP; SI Appendix, Fig. S6). Quantitatively, PT iTBS produced spinal LTP that is in line with reports of MEP facilitation in healthy humans after cortical iTBS (4); hippocampal slice studies, although the iTBS parameters were not identical to ours (29); and LTP at C-fiber dorsal horn synapses after tetanizing stimulation (30). Intriguingly, in progressive supranuclear palsy, LTP after MCX iTBS is elevated over healthy controls (31), suggesting normal limits to activity-dependent response augmentation. Our findings show robust CST spinal plasticity that can be further enhanced by local LTP in MCX, suggesting that the spinal cord can change the way descending MCX signals are processed in spinal premotor circuits.

The Segmental Representation of MCX Activation Is Dominated by the CST.

The MCX connects directly with the spinal cord via the CST and indirectly via brainstem relays in the red nucleus and reticular formation. In the context of the direct and indirect paths, how can their differential contributions to spinal plasticity after MCX stimulation be estimated? Whereas stimulation of the MCX could activate both the CST and brainstem projections, PT stimulation preferentially activates the CST. Additionally, PT lesion in the mouse eliminated the short-latency facilitation in forelimb muscles after MCX stimulation using stimulus-triggered averaging (32). This suggests that the initial response—despite a fast corticoreticulospinal conduction time associated with the indirect path in the rat (19) and cat (33)—is produced by the CST. Most studies only use PT stimulation to activate the spinal cord; here, we used both PT and MCX stimulation. MCX- and PT-evoked spinal LFPs had a similar topographic distribution of dorsal and intermediate negative responses (19). Moreover, regions with the highest CST termination density displayed the largest amplitude monosynaptic excitatory responses.

Our PT findings imply much less indirect path contributions to the segmental MCX response representation than for the direct CST, especially for the monosynaptic response (SI Appendix, Figs. S3 and S6). The rubrospinal tract’s cervical terminations are similar to those of the CST, suggesting similar spinal activation patterns. However, they are not likely to be effectively recruited by near-threshold MCX stimulation because corticorubral synapses on magnocellular red nucleus neurons are dendritically located with a slow rise time (34). By contrast, the dorsal negative CST monosynaptic response that inverted in the intermediate zone, like previous studies (19, 21, 35), is opposite the ventral negativity pattern following stimulation of the mesencephalic locomotor region (MLR) in the reticular formation, which mediates its spinal actions via the reticulospinal tracts (20).

At suprathreshold MCX currents, the response pattern expands into the ventral horn as a late negative LFP in the region of the wrist motor pools and medially adjoining sites. Although we used a triple-pulse stimulus with a short interpulse interval (36), this response also was observed with a single pulse, as was the late persistent dorsal response. Nevertheless, in addition to an oligosynaptic CST response, later events may also reflect indirect path contribution, including the motor pool response, since both the reticulo- and rubrospinal tracts have monosynaptic EPSPs with cervical motoneurons (37, 38). This cervical segmental representation to MCX activation provides a baseline for examining how spinal LTP can reshape the functional topography of descending CST signals.

Spinal Representation of MCX- and PT-Induced LTP.

We observed a significant enhancement of the monosynaptic MCX LFP, which we argue is localized predominantly to the CST–spinal interneuron synapse. If so, why does MCX iTBS produce substantially larger spinal LTP than PT iTBS, since both stimulation sites activate the CST pathway? An explanation is that MCX iTBS produces local LTP and efferent activity after iTBS is further enhanced by LTP at the CST–interneuron synapse. The observed magnitude of PT-induced spinal LTP is similar to MCX-induced spinal LTP after NMDA blockade (SI Appendix, Fig. S6). In the context of MCX neuromodulation to potentiate motor responses, the importance of MCX LTP is that, once produced, plasticity-inducing stimulation ought to be more effective in MCX because LTP will strengthen the same connections that are being activated to produce plasticity. Thus, MEP facilitation, the test probe for plasticity in human studies, can be mediated by local cortical circuits that respond to the stimulation with stronger activation of the MCX and its downstream targets. Well-documented MCX LTP (4, 25–27), together with our findings, strongly suggests that inducing plasticity in cortex not only leads to facilitation of descending signals, but those descending signals are further facilitated at the CST–spinal interneuron synapse.

Intraspinal contributions to LFP potentiation.

A late and persistent negative response was recorded within the dense central CST termination field after both PT and MCX stimulation. Its occurrence is not associated with an EMG response since it is evoked at both 0.8T and 1.2T; it was present with both the single-pulse (SI Appendix, Fig. S3) and the typical, triple-pulse probe stimulus. This response occurred during the late phase of the monosynaptic response and was consistently potentiated after iTBS. While presumed to be an oligosynaptic response that potentiates with the iTBS stimulation protocol, this could reflect activation of slow-conducting CST fibers or a slow-inactivating or persistent inward current, similar to what is reported for motoneurons (39).

A late phasic negative response in the wrist motor pool was recruited at 1.2T, emerging from the repolarizing phase of the positive-going source. Because of its suprathreshold recruitment current, as a percentage of baseline, it was larger than the dorsal monosynaptic response. There was a larger effect of NMDA blockade in MCX for this response than for the monosynaptic responses (SI Appendix, Fig. S6), which may reflect contributions by indirect brainstem pathways. Intriguingly, iTBS did not reduce EMG threshold and, accordingly, did not cause the emergence of the late negative ventral motor response at 0.8T. This is a consistent finding in the human literature, in which motor threshold remained stable after iTBS (25, 26) or after voluntarily increasing muscle tone (40). As in hippocampus, there may be differential regulation of baseline excitability and synaptic gain produced by LTP (41).

Functional and clinical implications.

Spinal premotor circuits can enhance descending MCX signals and change the way motoneurons are activated and, in turn, muscle contractions are produced. This does not diminish the role of MCX-intrinsic plasticity but, rather, stresses that the process of spinal circuit activation by the MCX is also under distal control at the level of the CST–interneuron synapse. The efficacy of CST synaptic connections with spinal circuits can be enhanced with noninvasive, cathodal, transspinal, direct current stimulation (9, 21, 42). And this approach strengthens MCX output after cervical spinal cord injury (42). The efficacy of long-term spinal neuromodulation to enhance functional outcomes after spinal cord injury, such as epidural stimulation, may tap into intraspinal plasticity like we observed in this study.

Materials and Methods

Animals.

All experiments were performed in accordance with the NIH’s Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (43). Care and treatment of the animals and procedures conformed to animal protocols approved by the City University of NY-Advanced Science Research Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. A total of 45 adult Sprague Dawley rats (250 to ∼320 g) provided data for this study (SI Appendix, Table S2). Rats were housed under a 12-h light/dark cycle in a pathogen-free area with ad libitum water and food. All surgeries were performed under general anesthesia (70 mg/kg ketamine, 6 mg/kg xylazine, intraperitoneal [i.p.]; discussed further under Anesthesia and Surgical Procedures) and aseptic conditions.

CST and CTB Tracing and Axon Labeling.

For CST tracing, under general anesthesia (70 mg/kg ketamine, 6 mg/kg xylazine, i.p.), a craniotomy (5 × 5 mm) was made over the distal forelimb area of MCX and biotinylated dextran amine (10,000 MW; Molecular Probes; 10% in 0.1M phosphate buffered saline [PBS]) was injected, as in our prior publications using a 2-wk survival time (9, 42) Rats were euthanized by an anesthetic overdose and perfused transcardially (300 mL saline followed by 500 mL 4% paraformaldehyde), and the cervical spinal cord sixth segment (C6) was removed and processed for tracer histochemistry. CST axon length was measured from regions of interest within the gray matter using an unbiased stereological estimate (Stereo Investigator; “Spaceball;” MBF Bioscience), similar to our earlier study (44). Measurements were made by laboratory personnel that were blind to the animal group. Regional CST axon length measurements for each section were exported to Matlab (The Math Works, Inc. MATLAB. Version 2019a). Custom Matlab scripts were written to generate a probability heatmap of local CST axon length, after correction for tracer efficacy (see Fig. 1A).

To label ECR motoneurons, we injected cholera toxin B (CTB) subunit (1% CTB, 10 µl; List Biologicals) unilaterally into the ECR using a Hamilton syringe using a 7-d survival time, similar to our previous study (45). CTB labeling was visualized using a primary antibody to CTB (goat anti-CTB; 1:1,000; List Biologicals), followed by an appropriate secondary antibody for immunofluorescence staining.

Anesthesia and Surgical Procedures.

Animals were anesthetized with a mixture of ketamine and xylazine (70 mg/kg ketamine, 6 mg/kg xylazine, i.p.). We chose this anesthesia protocol because, after completion of the surgical procedures, a single-ketamine supplement (50 mg/kg) results in stable anesthesia for at least the duration of a typical experiment (20 min). Importantly, this protocol does not significantly reduce MEP LTP produced by MCX iTBS compared with non-NMDA–blocking anesthetics (24). Rats were placed in a stereotaxic frame, with normal body temperature maintained with a circulating water bath–heating pad (37 °C). A craniotomy was made over the right forelimb representation area of MCX. The dura was partially removed, and a bipolar-stimulating electrode was placed epidurally over the distal forelimb area of the right MCX at a site that produced a small contralateral response in the ECR at the lowest threshold, as in our prior studies (45, 46). A laminectomy was made over C5 to C6, and the T1 vertebra was fixated with a spinal clamp. The overlying dura and arachnoid were cut at C6 and the pia microdissected to make a gap through which the electrode array was inserted. The anesthesia level was checked throughout the entire procedure by monitoring the breathing rate, the absence of vibrissae whisking, and the absence of hindlimb withdrawal to foot pinch.

MCX iTBS Stimulation.

iTBS was produced using a bipolar epidural–stimulating electrode (PlasticsOne, Inc), comprised of two stainless steel (0.005 in) wires that were bent to conform to the dural surface and partially deinsulated. The iTBS parameters were the same as previously used (9, 42): a burst of three pulses (ISI: 50 ms), repeated 10 times, for 2 s followed by 8 s off; this was repeated 20 times using a conventional pulse generator (A-M Systems; Model 3800). Stimulation intensity was adjusted to be 120% EMG threshold, which ensured activation from MCX to muscle for all stimulus presentations. In humans, changes in spinal excitability with MCX stimulation occurs with intensities of rTMS or electrical stimulation above threshold for evoking a motor response (47).

MCX Field Potential Recording and MCX NMDA Blockade.

To determine if spinal response enhancement is dependent, completely or partially, on MCX LTP, we used the glutamate NMDA receptor antagonist MK801 (300 mM; Tocris), compared with vehicle only (ACSF; Tocris) (48, 49). We followed a published protocol to ensure effective drug penetration, including a large craniotomy surface area that exceeded the forelimb representation of MCX (46), large drug concentration (48), and confirmed drug efficacy in layer 5 of MCX. The dura was partially removed so that the applied solutions could better penetrate into MCX to exert the maximal pharmacological effects. ACSF and MK801 (in ACSF) were warmed to 37 °C before applying to the pial surface. The compounds were allowed to incubate for 30 min before iTBS was administered. MCX field potentials were recorded using a monopolar microelectrode (EL3PT31.0H10; MicroProbes for Life Sciences, Inc), positioned between the two wires of the bipolar-stimulating electrode, and lowered to layer V (depth ∼1.5 mm from pial surface). A local reference electrode was placed on the dura. Baseline responses to MCX stimulation were obtained after applying the solution to the craniotomy and at all time courses following iTBS. In two experiments, we determined that MK801 did not alter baseline MCX excitability by recording evoked MCX LFPs to a single pulse and ECR MEP responses to MCX three-pulse stimulus probe at 1.2T before and after MK801 application (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). MCX LFP was measured as peak-to-peak amplitude (28).

Medullary Pyramid (PT) Stimulation.

PT stimulation was used to activate the CST relatively selectively (18). A concentric electrode (SSCEAX4-200; MicroProbes for Life Sciences, Inc.) was advanced to the target depth and adjusted to evoke a contralateral distal forelimb EMG response at the lowest current intensity (mean current, n = 5 rats; 0.14 ± 0.01 mA). In all experiments (n = 5), the concentric electrode was coated with 1,1′-Dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindocarbocyanine perchlorate (diI) to confirm the position of the electrode tip postmortem (see Fig. 4A). Our prior mouse study showed that PT transection eliminated short latency responses from wrist and biceps muscles, suggesting that stimulation at this site preferentially activates the direct CST pathway (32).

Multichannel Spinal Recording.

A four-shank silicon array (interrow electrode contact distance: 0.2 mm; intershank distance: 0.4 mm; NeuroNexus; A4 × 85mm-200–400-177-A32; SI Appendix, Fig. S1) was positioned 0.2 mm from the midline and inserted transversely into the left side of the spinal cord (contralateral to the cortical stimulation electrode) to a depth of 2 mm from the surface, as measured by initial pial contact with the electrode array. iTBS and the stimulus to probe response strength were performed using an epidural-stimulating electrode positioned over the wrist MCX (described under MCX iTBS Stimulation). Electrode positioning was carefully performed in all animals under a dissecting microscope to minimize interanimal electrode position differences and surface dimpling. We coated the array with a dye (diI; Molecular Probes; SI Appendix, Fig. S1) to identify its position postmortem (21). A unity gain head stage was connected via flexible cables to the spinal recording array; the wideband signals were amplified (1,000×) and low pass filtered (0.1 to 300 Hz) (OmniPlex-D system Plexon). The LFPs were digitized at a sampling frequency of 1 kHz and were notch filtered offline to remove 60 Hz noise (CED Inc; Spike) (21). We ensured that LFP recordings were not contaminated by muscle responses. The onset of ECR EMG responses occurred after the phasic portion of the LFPs; the mean latency was 13.44 ± 0.34 ms (n = 10 rats) (SI Appendix, Table S1). We verified that there was no EMG signal contamination in the LFP recordings. We attribute this to selective recordings of electrical signals from those neurons in close vicinity of each microelectrode on the silicon electrode array and proper grounding to eliminate/minimize contamination by EMG. Moreover, reafferent signals would have occurred only with suprathreshold stimulation, yet comparison of 0.8T and 1.2T showed no evidence for EMG signal contamination in the LFP recordings.

LFP Measurements and Criteria.

We recorded LFPs evoked by an MCX and PT stimulus probe, which was a train of three stimuli (biphasic pulses, 0.2 ms per phase, 0.5 Hz repetition rate, and 3 ms interstimulus interval for pulses). The three-stimulus probe did not, by itself, produce plasticity (SI Appendix, Fig. S2B) and, compared with a single-stimulus probe, enabled the use of lower currents (∼25% reduction). Moreover, the LTP that we report is not dependent on the use of the three-stimulus probe, since we also observed comparable LTP using a single-stimulus probe (SI Appendix, Fig. S3).

We characterized the LFPs based on their initial direction and relative times of occurrence. Negative LFPs, or current sinks, correspond to intracellularly recorded depolarizations (20). The descending CST volley is not present in the cervical enlargement in the rat, likely reflecting temporal dispersion of signals because of unmyelinated and thinly myelinated CST axons (19). In consequence, there is no reliable segmental delay measurement for rodents (19). Three classes of negative LFP were recorded from three ROIs. 1) Initially negative deflection with a single peak that returned to baseline (see Fig. 1 A and B, green ROI). This is a monosynaptic field because it was not preceded by any earlier field. The current source for this initially negative monosynaptic response is a broadly distributed, ventral, and lateral positive response, as reported in other studies (19–21). 2) Initially negative, monosynaptic deflection with a single peak, like the first LFP type, but was followed by a late negative plateau (see Fig. 1 A and B, magenta ROI). 3) Delayed negative deflection, which was consistently recorded in the ventral intermediate zone and lateral ventral horn. It was preceded by the monosynaptic source (see Fig. 1 A and B, blue ROI). Each LFP type was evoked by either MCX or PT stimulation but with a longer latency with MCX stimulation.

The negative/depolarizing LFPs for each recording channel of the array were measured as the negative area above the LFP voltage trace (between the stimulus onset, for 90 ms) using custom-written scripts in Spike2 (version 8; CED, Inc) and Matlab. This method permits the same analysis for initially negative, monosynaptic, and delayed responses (e.g., after preceding source positivity). The integral is also commonly used for spinal recordings (50). MCX/PT stimulation–evoked spinal LFPs from each recording site of the array (see Fig. 1A for MCX stimulation) were averaged (n = 20 trials). The stimulation parameters were kept the same before and after iTBS for each animal. LFP values were used for three purposes: 1) comparisons of raw traces and differential values (i.e., LFP post-iTBS minus LFP pre-iTBS); 2) for constructing two-dimensional, MCX-evoked spinal activity maps (see Fig. 1D; grayscale heatmaps) and difference maps (see Fig. 2C); and 3) raw voltage values were used to construct movies (Movies S1–S4) that represent time-varying LFP voltage values. Response maps were plotted using GraphPad Prism (version 8.0.1 for Mac OS X, GraphPad Software). Potentiation was expressed as the percent of baseline across the three ROIs (see Fig. 2D).

The period of time for the experiment—between finalizing electrode positions and stimulation parameters and completing the last test for LFP changes—was ∼20 min. Anesthesia supplementation was administered before initiating the experimental stimulation protocol. To verify that MCX-evoked LFPs remained stable during this period, we recorded responses immediately after an anesthesia supplement to a 1.2T stimulus separated by 20 min. Representative LFPs within a single-electrode track are shown for initial recordings (black) and 20 min later (gray; SI Appendix, Fig. S2A). We measured the onset latency (time when the voltage was >2 SDs below the computed baseline during the 10-ms period before the stimulus). The response latency and time to peak negativity for the two time points remained unchanged. There was a small reduction in the initial ventral positivity, which is the current source for the dorsal negativity. Although we often recorded for a period longer than 20 min, analyses were not performed because of the potential for lightening of the anesthesia level. Animals were euthanized thereafter and electrode locations verified.

LFP Movies.

We generated movie files to show the time-varying change in raw LFP amplitude after stimulation and during the time period following iTBS (Movies S1–S4). Raw LFP traces at each electrode site were averaged (10 ms before stimulus onset to 90 ms; n = 20 stimuli). Heat maps were constructed based on the integrated LFP values. In these movies, the peak source signal (positivity) is coded cyan and negativity red.

EMG Recording.

EMG responses (MEP) were recorded in the ECR using percutaneous nickel–chrome wire electrodes (deinsulated 1 mm from the tip), in response to trains of stimuli to the contralateral MCX and PT. Threshold is defined as the current amplitude that evoked responses in 50% of the trials that exceeded ∼0.05 mV (45). Current values used to study spinal and muscle responses were based on this threshold and were not changed throughout the experiment. Current thresholds for all experiments are summarized in SI Appendix, Table S3.

Statistical Analyses.

All data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism. Data were checked for normality using the Shapiro–Wilks test. To test the effects of iTBS on spinal LFPs at the different recording sites under the three experimental conditions (MCX iTBS, MCX iTBS + MK801, and PT iTBS), we analyzed data within three ROIs. LFP values as a percent of baseline for the three ROIs were tested using Friedman’s repeated measures ANOVA to examine the difference between all time courses versus baseline. The significant differences at each time point were tested by post hoc Dunn’s test. Kruskal–Wallis and post hoc Dunn’s multiple comparison tests were conducted to test for statistical significance in the percent of baseline peak-to-peak amplitude at 10 and 15 min, comparing MCX LFP with iTBS + ACSF and iTBS + MK801. Error bars indicate mean ± the SEM. P values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Xiuli Wu for histology. Research grants from the following funding agencies provided suppport for our experiments: NIH NINDS (2R01NS064004 to J.H.M.) and New York State Department of Health Spinal Cord Injury Board (C030606GG to J.H.M. and C30860GG to A.A.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2113192118/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability

All study data are included in the article and/or supporting information.

References

- 1.Kleim J. A., et al. , Cortical synaptogenesis and motor map reorganization occur during late, but not early, phase of motor skill learning. J. Neurosci. 24, 628–633 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chakrabarty S., Martin J. H., Postnatal development of the motor representation in primary motor cortex. J. Neurophysiol. 84, 2582–2594 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rioult-Pedotti M. S., Friedman D., Donoghue J. P., Learning-induced LTP in neocortex. Science 290, 533–536 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang Y.-Z., Edwards M. J., Rounis E., Bhatia K. P., Rothwell J. C., Theta burst stimulation of the human motor cortex. Neuron 45, 201–206 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iriki A., Pavlides C., Keller A., Asanuma H., Long-term potentiation in the motor cortex. Science 245, 1385–1387 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rioult-Pedotti M. S., Friedman D., Hess G., Donoghue J. P., Strengthening of horizontal cortical connections following skill learning. Nat. Neurosci. 1, 230–234 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suppa A., et al. , Ten years of theta burst stimulation in humans: Established knowledge, unknowns and prospects. Brain Stimul. 9, 323–335 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vékony T., et al. , Continuous theta-burst stimulation over the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex inhibits improvement on a working memory task. Sci. Rep. 8, 14835 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Song W., Amer A., Ryan D., Martin J. H., Combined motor cortex and spinal cord neuromodulation promotes corticospinal system functional and structural plasticity and motor function after injury. Exp. Neurol. 277, 46–57 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Funke K., Benali A., Modulation of cortical inhibition by rTMS - Findings obtained from animal models. J. Physiol. 589, 4423–4435 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benali A., et al. , Theta-burst transcranial magnetic stimulation alters cortical inhibition. J. Neurosci. 31, 1193–1203 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bestmann S., Krakauer J. W., The uses and interpretations of the motor-evoked potential for understanding behaviour. Exp. Brain Res. 233, 679–689 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nudo R. J., Milliken G. W., Jenkins W. M., Merzenich M. M., Use-dependent alterations of movement representations in primary motor cortex of adult squirrel monkeys. J. Neurosci. 16, 785–807 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ziemann U., Wittenberg G. F., Cohen L. G., Stimulation-induced within-representation and across-representation plasticity in human motor cortex. J. Neurosci. 22, 5563–5571 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolpaw J. R., Tennissen A. M., Activity-dependent spinal cord plasticity in health and disease. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 24, 807–843 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolpaw J. R., The negotiated equilibrium model of spinal cord function. J. Physiol. 596, 3469–3491 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nishimura Y., Perlmutter S. I., Eaton R. W., Fetz E. E., Spike-timing-dependent plasticity in primate corticospinal connections induced during free behavior. Neuron 80, 1301–1309 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iriki A., Keller A., Pavlides C., Asanuma H., Long-lasting facilitation of pyramidal tract input to spinal interneurons. Neuroreport 1, 157–160 (1990). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alstermark B., Ogawa J., Isa T., Lack of monosynaptic corticomotoneuronal EPSPs in rats: Disynaptic EPSPs mediated via reticulospinal neurons and polysynaptic EPSPs via segmental interneurons. J. Neurophysiol. 91, 1832–1839 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Noga B. R., et al. , Field potential mapping of neurons in the lumbar spinal cord activated following stimulation of the mesencephalic locomotor region. J. Neurosci. 15, 2203–2217 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song W., Martin J. H., Spinal cord direct current stimulation differentially modulates neuronal activity in the dorsal and ventral spinal cord. J. Neurophysiol. 117, 1143–1155 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Larkum M. E., Launey T., Dityatev A., Lüscher H. R., Integration of excitatory postsynaptic potentials in dendrites of motoneurons of rat spinal cord slice cultures. J. Neurophysiol. 80, 924–935 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McKenna J. E., Prusky G. T., Whishaw I. Q., Cervical motoneuron topography reflects the proximodistal organization of muscles and movements of the rat forelimb: A retrograde carbocyanine dye analysis. J. Comp. Neurol. 419, 286–296 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fujiki M., Kawasaki Y., Fudaba H., Continuous theta-burst stimulation intensity dependently facilitates motor-evoked potentials following focal electrical stimulation of the rat motor cortex. Front. Neural Circuits 14, 585624 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hasan A., et al. , Direct-current-dependent shift of theta-burst-induced plasticity in the human motor cortex. Exp. Brain Res. 217, 15–23 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Di Lazzaro V., et al. , Modulation of motor cortex neuronal networks by rTMS: Comparison of local and remote effects of six different protocols of stimulation. J. Neurophysiol. 105, 2150–2156 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Di Lazzaro V., et al. , The physiological basis of the effects of intermittent theta burst stimulation of the human motor cortex. J. Physiol. 586, 3871–3879 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu C.-W., Chiu W.-T., Hsieh T.-H., Hsieh C.-H., Chen J.-J. J., Modulation of motor excitability by cortical optogenetic theta burst stimulation. PLoS One 13, e0203333 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abraham W. C., Huggett A., Induction and reversal of long-term potentiation by repeated high-frequency stimulation in rat hippocampal slices. Hippocampus 7, 137–145 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu X. G., Sandkühler J., Long-term potentiation of C-fiber-evoked potentials in the rat spinal dorsal horn is prevented by spinal N-methyl-D-aspartic acid receptor blockage. Neurosci. Lett. 191, 43–46 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Conte A., et al. , Abnormal cortical synaptic plasticity in primary motor area in progressive supranuclear palsy. Cereb. Cortex 22, 693–700 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gu Z., et al. , Control of species-dependent cortico-motoneuronal connections underlying manual dexterity. Science 357, 400–404 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jankowska E., Stecina K., Cabaj A., Pettersson L.-G., Edgley S. A., Neuronal relays in double crossed pathways between feline motor cortex and ipsilateral hindlimb motoneurones. J. Physiol. 575, 527–541 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsukahara N., Fujito Y., “Synaptic plasticity in the red nucleus” in Neuronal Plasticity, Cottman C. W., Ed. (Raven Press, 1978), pp. 113–130. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chakrabarty S., Martin J. H., Postnatal development of a segmental switch enables corticospinal tract transmission to spinal forelimb motor circuits. J. Neurosci. 30, 2277–2288 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Illert M., Lundberg A., Tanaka R., Integration in descending motor pathways controlling the forelimb in the cat. 2. Convergence on neurones mediating disynaptic cortico-motoneuronal excitation. Exp. Brain Res. 26, 521–540 (1976). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Williams P. T. J. A., Kim S., Martin J. H., Postnatal maturation of the red nucleus motor map depends on rubrospinal connections with forelimb motor pools. J. Neurosci. 34, 4432–4441 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Riddle C. N., Baker S. N., Convergence of pyramidal and medial brain stem descending pathways onto macaque cervical spinal interneurons. J. Neurophysiol. 103, 2821–2832 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Theiss R. D., Kuo J. J., Heckman C. J., Persistent inward currents in rat ventral horn neurones. J. Physiol. 580, 507–522 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Devanne H., Lavoie B. A., Capaday C., Input-output properties and gain changes in the human corticospinal pathway. Exp. Brain Res. 114, 329–338 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carvalho T. P., Buonomano D. V., Differential effects of excitatory and inhibitory plasticity on synaptically driven neuronal input-output functions. Neuron 61, 774–785 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zareen N., et al. , Motor cortex and spinal cord neuromodulation promote corticospinal tract axonal outgrowth and motor recovery after cervical contusion spinal cord injury. Exp. Neurol. 297, 179–189 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.National Research Council, Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Academies Press, Washington, DC, ed. 8, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carmel J. B., Berrol L. J., Brus-Ramer M., Martin J. H., Chronic electrical stimulation of the intact corticospinal system after unilateral injury restores skilled locomotor control and promotes spinal axon outgrowth. J. Neurosci. 30, 10918–10926 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jiang Y.-Q., Zaaimi B., Martin J. H., Competition with primary sensory afferents drives remodeling of corticospinal axons in mature spinal motor circuits. J. Neurosci. 36, 193–203 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brus-Ramer M., Carmel J. B., Martin J. H., Motor cortex bilateral motor representation depends on subcortical and interhemispheric interactions. J. Neurosci. 29, 6196–6206 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Berardelli A., et al. , Facilitation of muscle evoked responses after repetitive cortical stimulation in man. Exp. Brain Res. 122, 79–84 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Harrison T. C., Ayling O. G. S., Murphy T. H., Distinct cortical circuit mechanisms for complex forelimb movement and motor map topography. Neuron 74, 397–409 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hasan M. T., et al. , Role of motor cortex NMDA receptors in learning-dependent synaptic plasticity of behaving mice. Nat. Commun. 4, 2258 (2013). Correction in: Nat. Commun. 4, 2831 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bączyk M., Jankowska E., Long-term effects of direct current are reproduced by intermittent depolarization of myelinated nerve fibers. J. Neurophysiol. 120, 1173–1185 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article and/or supporting information.