Significance

Proteins are produced by ribosomes in the cell, and during this process, can begin to adopt their biologically active forms assisted by molecular chaperones such as trigger factor. This fundamental cellular mechanism is crucial to maintaining a functional proteome and avoiding deleterious misfolding. Here, we study how disordered nascent chains emerge from the ribosome exit tunnel, and find that interactions with the ribosome surface dominate their dynamics in vitro and in vivo. Moreover, we show that the types of amino acids that mediate such interactions are also those that recruit trigger factor. This lays the foundation to describe how nascent chains are handed over from the ribosome surface to chaperones during biosynthesis within the crowded cytosol.

Keywords: cotranslational folding, NMR spectroscopy, structural biology, alpha synuclein, in-cell NMR

Abstract

In the cell, the conformations of nascent polypeptide chains during translation are modulated by both the ribosome and its associated molecular chaperone, trigger factor. The specific interactions that underlie these modulations, however, are still not known in detail. Here, we combine protein engineering, in-cell and in vitro NMR spectroscopy, and molecular dynamics simulations to explore how proteins interact with the ribosome during their biosynthesis before folding occurs. Our observations of α-synuclein nascent chains in living Escherichia coli cells reveal that ribosome surface interactions dictate the dynamics of emerging disordered polypeptides in the crowded cytosol. We show that specific basic and aromatic motifs drive such interactions and directly compete with trigger factor binding while biasing the direction of the nascent chain during its exit out of the tunnel. These results reveal a structural basis for the functional role of the ribosome as a scaffold with holdase characteristics and explain how handover of the nascent chain to specific auxiliary proteins occurs among a host of other factors in the cytosol.

The ribosome, the macromolecular machine responsible for polypeptide synthesis, also acts as a universal hub to coordinate a range of cotranslational processes including processing, folding, and targeting (1). The structural bases of these auxiliary functions have been explored, although many questions remain open. An elongating nascent chain (NC) interacts with the interior of the narrow ribosomal tunnel (2) before emerging into the cytosol, where it continues to experience the influence of the ribosome through transient interactions with its outer surface. The negative electrostatic potential of the ribosome, originating from its RNA as well as the overall negatively charged surface-exposed residues of its proteins, can mediate NC interactions (3–5). These interactions can influence cotranslational folding processes, likely through the stabilization of the disordered conformations prevalent in incomplete polypeptide chains, and can even delay native structure formation (6–8) and molecular assembly of protein complexes (9). Once an NC is sufficiently emerged, its folding can also be assisted by ribosome-associated molecular chaperones, such as the trigger factor (TF) present within Escherichia coli, which is thought to facilitate this process by acting as a holdase (10).

We have previously initiated an investigation examining the molecular basis of NC interactions made with the ribosome surface by studying a biosynthetic snapshot of α-synuclein (αSyn) (4). αSyn, whose aggregation is a pathological hallmark of Parkinson’s disease (11) consists of an N-terminal, amphipathic region, which is predominantly positively charged due to a range of imperfect “KTKEGV” repeats, a central hydrophobic region, known as non-Aβ component (NAC), and a negatively charged C-terminal region (Fig. 1A). As an intrinsically disordered protein (IDP), αSyn allows an analysis at the residue-specific level of NC-ribosome interactions in the absence of complex folding processes (4). The abundance of lysine residues within its seven-repeat motif also offers the possibility to interrogate the impact of charge reversal on its properties. Using NMR spectroscopy, a powerful technique to characterize the conformational properties of an emerging NC (6, 12, 13), we determined at atomic resolution an NMR-restrained three-dimensional structural ensemble of this disordered ribosome-bound NC (RNC). Combined with a systematic analysis of the effects of electrostatic charge, aromaticity, and NC length, as underpinned by all-atom molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, we describe a residue-specific dissection of NC-ribosome interactions. We find, using a comparative analysis of NC-ribosome and RNC-TF interactions, that the ribosome shares characteristics that similarly define TF’s known holdase activity. Using in-cell NMR spectroscopy of live E. coli cells, we then show that NC interaction sites identified in purified RNCs in vitro are likely retained in actively translating RNCs in vivo. We thus conclude that during biosynthesis, positively charged and aromatic residues in emerging NCs are key signatures that can modulate interactions formed with the ribosome surface and during handover to auxiliary factors such as TF.

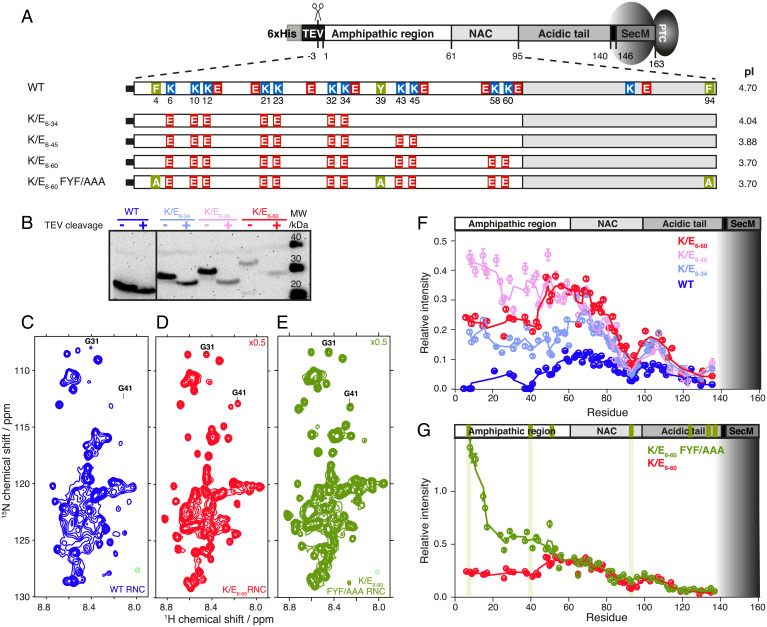

Fig. 1.

Charged and aromatic residues determine NC-ribosome interactions in αSyn. (A) Charge variants used to investigate the effects of electrostatic forces on NC interactions, highlighting the 11 Lys residues of the amphipathic region of αSyn (1 to 60) that were mutated to Glu residues. The K/E6–60 FYF/AAA variant has aromatic residues replaced with Ala. (B) Anti-SecM Western blot of the αSyn RNC mutants (before and after TEV protease cleavage). (C–E) 1H, 15N-SOFAST-HMQC spectrum of the WT αSyn RNC, K/E6–60 (scaled 0.5× relative to WT, red), and K/E6–60 FYF/AAA αSyn RNCs (scaled 0.5× relative to WT, green) at 700 MHz and 277 K. G31 and G41 are indicated as representative examples of the assigned resonances. (F) Cross-peak intensities of αSyn RNCs relative to the corresponding isolated protein in the presence of 70S ribosomes: WT (blue), K/E6–34 (light blue), K/E6–45 (pink), and K/E6–60 αSyn (red). Three-point moving averages are shown. The gray shaded area depicts the part of the RNC sequence confined within the ribosomal exit tunnel. (G) Same plot as F but showing K/E6–60 (red) and K/E6–60 FYF/AAA αSyn (green) RNCs. The positions of the aromatic residues within αSyn are indicated in green boxes on the top bar, and those mutated to Ala are indicated using additional vertical green lines.

Results

αSyn NC Interactions with the Ribosome Are Modulated by Charged and Aromatic Residues.

We set out to investigate the contribution of electrostatic forces in modulating ribosome-NC interactions using αSyn (4). The αSyn N-terminal amphipathic region is mildly basic through its imperfect KTKEGV repeats while the RNA-rich ribosome surface is highly negatively charged. Initially, we replaced 11 positively charged Lys (K) residues with negatively charged Glu (E) residues within the sequence of the N-terminal amphipathic region of αSyn (residues 1 to 61) (Fig. 1A and SI Appendix, Fig. S1A), reversing the net positive charge in the amphipathic region from +4 in WT αSyn to a net negative charge of −18 for K/E6–60 at physiological pH (Fig. 1A). Two intermediate variants, K/E6–34 (net charge −10) and K/E6–45 (net charge −14), were also investigated for the effects of local charge. 15N-labeled, SecM-arrested ribosome-NC complexes (RNCs) of the charge variants were generated in E. coli and purified to homogeneity (4, 14) (Fig. 1B). 1H,15N correlation SOFAST-HMQC spectra of the WT αSyn RNCs (4) as well as the variant RNCs K/E6–34, K/E6–45, and K/E6–60 showed narrowly dispersed resonances with negligible chemical shift perturbations relative to their corresponding isolated proteins. These results indicate that similar disordered states are accessible to the RNC charge variants relative to that of the WT (Fig. 1 C and D and SI Appendix, Fig. S1).

Next, the NMR signal intensities within these RNC spectra were used to probe NC-ribosome interactions (Fig. 1F). Transferred relaxation due to transient interactions with the large ribosome particle leads to attenuation of NMR signal intensities. At the N terminus within the amphipathic and NAC regions, increases in signal intensities were observed for the K/E6-34, K/E6-45, and K/E6-60 RNCs as compared to those of the WT αSyn RNC, while the most C-terminal residue observable, D135 (28 residues from the peptidyl transferase center [PTC]), remained unchanged. These data indicate that the dynamic character of the emerged NC sequence can be attenuated by the ribosomal surface in a residue-specific manner (Fig. 1 A and F) with the observed modulations originating from a repulsive electrostatic effect between the negatively charged ribosomal surface and segments of the negatively charged NC. For the region between residues E61-D135, which is beyond the sites of mutation, the magnitude of the intensity changes correlated with the progressive addition of negative charge to the αSyn NC (Fig. 1F). While the same effect was also observed within the N-terminal region, surprisingly, the N-terminal region of K/E6–60 RNC shows significantly lower average resonance intensities relative to K/E6–45 RNC (∼40% less, Fig. 1F), despite this pair of RNCs sharing the same sequence within their first 48 residues. These findings indicate that, despite its higher negative charge, the N-terminal region of the K/E6–60 variant is more motionally restricted relative to that of the K/E6–45 variant, implying that electrostatic interactions between positively charged NC residues and the largely negatively charged ribosome surface may not be the only factor responsible for modulating the dynamics of the disordered αSyn NC.

The sites that remained broadened within all the αSyn RNC variants correlated with segments containing aromatic residues present in the native sequence (F4, Y39, H50, F94, Y125, Y133, Y136, Fig. 1 A and G, green). We examined the extent to which three N-terminal aromatic residues with strongly broadened resonances (F4, Y39, F94) contributed to interactions with the ribosome surface by substituting these residues with Ala within a K/E6–60 background (Fig. 1 E and G). At the N terminus, the F4A and Y39A mutations in the K/E6–60 FYF/AAA RNC showed a dramatic effect on the intensity profile consistent with a major local disruption of these aromatic residue-mediated interactions with the ribosome surface. At the C terminus between residues E60 and D135, the FYF/AAA substitution showed only a very small increase in intensity localized around the F94A mutation site, and it is likely that the two flanking, positively charged residues K96 and K97 contribute to an attractive effect with the ribosome at this site (Fig. 1G and Identification of NC Interaction Sites on the Ribosome).

This residue-specific dissection of NC-ribosome interactions using the αSyn RNC scaffold demonstrates that an interplay exists between charge and aromaticity, which modulates the interaction propensities of NCs when bound to the ribosome.

Nascent Chain-Ribosome Interactions Persist During Elongation.

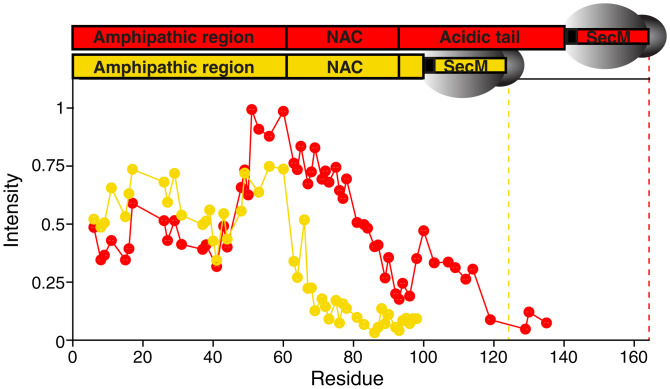

To investigate how interactions are formed with the ribosomal surface as an NC emerges progressively from the exit tunnel, we evaluated an earlier snapshot of biosynthesis in which only the first 100 residues are translated (denoted: 1–100 RNC) (SI Appendix, Fig. S2A). The resulting intensity profiles of a K/E6–60 1–100 RNC followed a similar trend to that of full-length K/E6–60 αSyn for the N-terminal residues 1 to 60 only (Fig. 2A and SI Appendix, Fig. S2 B–H), suggesting that the NC sequence, rather than the proximity to the ribosome, was the strongest determinant of interactions. Beyond this point, the intensity plots deviate significantly, where a progressive decrease in intensity was seen in the 1–100 RNC, suggesting that a decreased mobility toward the C terminus exists and is likely a result of NC tethering to the ribosome particle. Indeed, despite differences in their C-terminal sequences, both NCs were similarly affected by the confines of the exit tunnel, leading to strongly attenuated intensities up until ∼40 residues from the PTC. These results suggest that any ribosome tethering effects are largely sequence independent. Overall, we observe that, once the NC has sufficiently emerged to overcome the effects of both ribosome tunnel confinement and tethering, the amino acid sequence of the emerged segment, rather than its proximity to the ribosomal body, is the main determinant of ribosome interactions.

Fig. 2.

Length-dependence of αSyn NC interactions with the ribosome surface. (A) Comparison of the normalized 1H,15N-SOFAST-HMQC intensities (700 MHz, 277 K) of the full-length K/E6–60 RNC (red, containing αSyn residues 1 to 140) and the truncated K/E6–60 1–100 RNC (yellow). The dotted line indicates the most C-terminal residue in each construct.

Identification of NC Interaction Sites on the Ribosome.

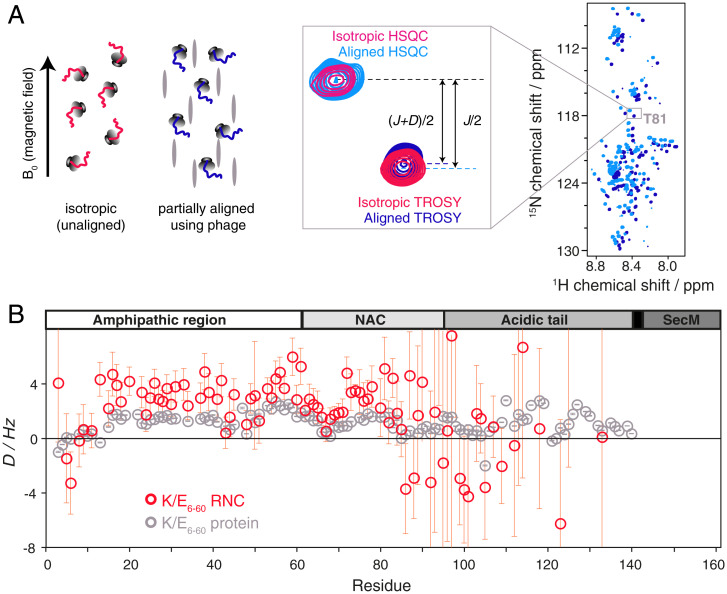

In order to provide a structural basis for these observed interactions (Fig. 1F), we measured NMR residual dipolar couplings (RDCs) for backbone amide resonances in the K/E6–60 RNC, a strategy also recently applied to the ribosome-bound multicopy bL12 stalk protein (15) that is responsible for binding GTPase translation factors such as elongation factor G. These RDCs depend on the average orientation of the N-H bond vector when aligned in an anisotropic medium and so contain both short-range and long-range structural information.

Following alignment of the K/E6–60 RNC in Pf1 phage, 85 RDCs could be determined for residues between V3 and Y133 (Fig. 3). Comparison of these RDCs with those measured for the isolated K/E6–60 protein in the same alignment medium reveals interesting similarities and differences that provide additional insights into the influence of the ribosome on the conformational and dynamic properties of the NC. The RDCs for residues in the N-terminal half of the protein show a similar overall profile for the NC and the free protein, characterized by small-magnitude and almost exclusively positive RDC values. Such RDC profiles are typical for IDPs (16) although the deviations from a smooth, featureless profile are indicative of conformational biases away from a truly random ensemble, for example, due to transient long-range interactions between different regions of the polypeptide chain. Some of the more prominent local features in the RDC profile of the isolated protein—such as the two dips centered on residues 44 and 67—are reproduced in the profile of the RNC, indicating that the conformational biases in the N-terminal region of the isolated protein are at least partially preserved in the NC. In contrast, however, the overall magnitude of the RDCs measured on the NC is noticeably larger than for the isolated protein (while the strength of alignment was slightly greater for the RNC, as reported by the 2H splittings, the relative increase in the magnitude of the RDCs in the N-terminal part of protein in its ribosome-bound form is significantly larger). This difference is due to the subtle influence of the ribosome on the conformational sampling of the polypeptide chain. The N-terminal part of the NC is sufficiently distant from the vestibule of the exit tunnel to assume that purely steric restrictions due to the presence of the ribosome core particle are likely negligible; hence, ribosome-induced perturbations to the conformational sampling of the NC can be attributed to the transient interactions between the NC and the surface of the ribosome. While the NMR signal intensities clearly show that these interactions between the NC and the ribosome are weaker for the K/E6–60 mutant than the wild-type protein, they still appear to be of sufficient strength to perturb the overall RDC profile relative to the isolated protein.

Fig. 3.

Orientational preferences of the K/E6–60 αSyn RNC from RDC measurements. (A) Schematic representation of the RDC experiments used to determine the orientational preferences of the RNC. Measurements are made on RNCs in both unaligned and partially aligned states with respect to the magnetic field of the NMR spectrometer using bacteriophage (represented as gray ovals). Overlay of the 1H,15N-HSQC and TROSY spectra of the K/E6–60 αSyn RNC (950 MHz, 277 K) aligned in the presence of 15.1 mg/mL−1 bacteriophage Pf1 (light blue/blue). A magnified view is centered on resonance T81 and additionally overlaid with unaligned (isotropic) spectra (magenta/red). The dipolar coupling D is inferred from the difference between the isotropic splittings (J-coupling only) and the partially aligned splittings (J+D). (B) N-HN RDCs measured on the K/E6–60 αSyn RNC (red) and on the isolated K/E6–60 protein (gray). Uncertainties are derived from 15N peak linewidths and signal-to-noise ratios (and hence are large for weak intensity, C-terminal RNC resonances).

Beyond residue 85, the RDCs of the NC begin to deviate more drastically from those of the isolated protein, with several residues of the NC showing negative RDCs. While the measurement uncertainties for the RDCs of these more C-terminal residues are inevitably larger than for those in the N-terminal half of the NC, the number of the residues showing negative RDCs is significant. The dominant factor governing the large deviations observed between the RDC profiles of the free protein and the NC is probably the steric influence of the ribosome on the conformational sampling of the NC, together with the effects of its C-terminal tethering the ribosome. Nevertheless, semispecific charge-mediated or aromatic interactions with the ribosome surface, as revealed in the N-terminal part of the NC, are likely to persist in the C-terminal part; as such, the overall observed RDC profile of the NC depends on a complex interplay of ribosome-mediated effects. However, the RDCs can be incorporated as experimental restraints within all-atom MD simulations to generate ab-initio the conformational ensemble of the NC.

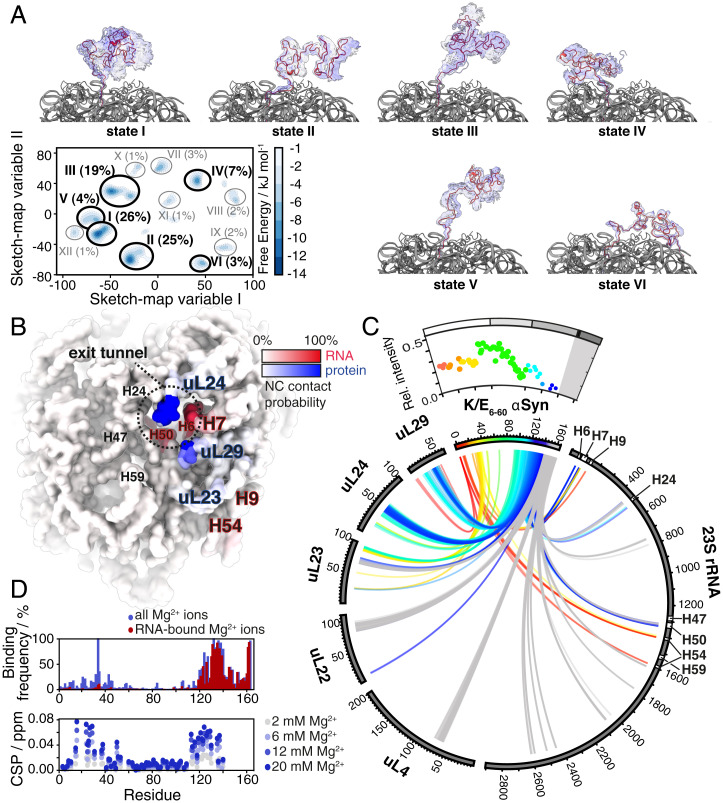

RDCs from 63 non overlapped peaks and spanning the sequence between Glu6-Gln109 were selected as structural restraints in all-atom MD simulations, employing a ribosome structural model comprised of the exit tunnel as well as the outer ribosome surface accessible to the NC (Fig. 4A and Methods). A well-tempered bias-exchange metadynamics scheme (17–19) with six replicas was used, with each sampling one unique collective variable (CV) (SI Appendix, Fig. S4A) for 325 ns, resulting in ∼2 µs of total MD simulation time. The resulting structural ensemble is in good agreement between back-calculated backbone amide chemical shifts with those derived experimentally (SI Appendix, Fig. S4B). Upon analysis of the entire trajectory, we find that the K/E6–60 αSyn NC samples a range of significantly disordered conformations (Fig. 4A) with very few intrachain contacts observed and mostly located within the hydrophobic NAC region (SI Appendix, Fig. S4C).

Fig. 4.

RDC-restrained all-atom MD simulation of an αSyn RNC. (A) Free energy landscape of the αSyn K/E6–60 RNC (represented in sketch-map variable space; see Methods); we also show the structures of the six most populated states in the landscape. (B) Surface map of the ribosome, highlighting the NC interaction sites according to binding frequency, with rRNA (red) and ribosomal proteins (blue). (C) Circular plot representing all interactions (defined as two atoms closer than 4.5 Å) between the αSyn K/E6–60 NC and the ribosome, rainbow-colored by primary sequence. The αSyn K/E6–60 RNC relative cross-peak intensities from NMR experiments (as in Fig. 1F) are shown above the circular plot for reference. (D, Top) Mg2+-bound population of the NC residues (defined using a 4.5 Å cutoff distance) in the MD trajectory. (D, Bottom) Chemical shift perturbations in the 1H,15N-SOFAST-HMQC of isolated K/E6–60 αSyn protein in the presence of Mg2+.

We then applied sketch-map analysis (20) to the NC trajectory in order to extract the most sampled and structurally distinct microstates from its complex free energy landscape (Fig. 4A) and describe their interactions with the ribosome as a representative behavior of the NC across the entire ensemble (Fig. 4 B and C and SI Appendix, Fig. S4C). We found that the 12 most sampled microstates are characterized by extensive structural heterogeneity (Fig. 4A) but nevertheless ones in which the αSyn NC is observed to bind to distinct sites on the ribosome.

Of the NC segment comprising residues 1 to 121, which extend well beyond the exit tunnel, we observed contacts with the ribosome in circa 7% of the conformations, with the most persistent of these localized to several ribosomal proteins, including uL29, uL24, and an unstructured C-terminal region of ribosomal protein uL23, as well as helices H7, H9, and H54 of the 23S ribosomal RNA (rRNA). Toward the C terminus, the NC segment comprising residues 122 to 130 is found in the immediate vicinity of the exit tunnel vestibule and therefore experiences an increased extent of contacts (ranging from 10% up to 70%) with the ribosome surface. These contacts center on ribosomal proteins uL24 and uL29 and 23S rRNA helices H7 and H50 (Fig. 4 B and C). Within the exit tunnel, the aSyn NC residues 131 to 140 interact extensively with several regions of the 23S rRNA and also with ribosomal protein uL23. Generally, we find that the αSyn segments that interact with the ribosome surface correspond well to those that report reductions in NMR intensities (Fig. 4C). The nature of these interactions is defined by charge-charge, polar, and hydrophobic contacts (SI Appendix, Fig. S4E), and their localization suggests that the NC preferentially exits the ribosome along a more protein-rich region of the exit port (Fig. 4B and SI Appendix, Fig. S4D).

Further inspection of the structures also revealed that in >6% of these conformations, charge interactions are observed between αSyn residues K96 and K97 with residues E59 and D17, respectively, of ribosomal protein uL24 (SI Appendix, Fig. S4E). This result may account for the absence of a major effect of the F94A mutation, which did not lead to a significant increase in the intensity profile of the αSyn mutant RNC, as described previously (Fig. 1G).

Moreover, the structures reveal that the highly negatively charged N-terminal and C-terminal segments of the NC associate with Mg2+ ions (Fig. 4D and SI Appendix, Fig. S4F), of which >170 encase the 70S E. coli ribosome particle (21). A structural analysis shows that NC-Mg2+ contacts occurred almost exclusively in a transient manner and are coordinated via water molecules, aside from a few exceptions such as Glu37 and Glu134, which were observed to bind Mg2+ directly. The majority of Mg2+ ions were found to mediate interactions formed between the NC and rRNA (e.g., Glu123 with rRNA A95) (SI Appendix, Fig. S4F) and to a lesser extent, also facilitated intra-NC interactions (e.g., between Leu8 and Glu10, SI Appendix, Fig. S4F). These same N-terminal and C-terminal regions of the αSyn K/E6–60 NC, seen to interact with Mg2+ also showed NMR chemical shift perturbations when Mg2+ ions were titrated into isolated αSyn K/E6–60 (Fig. 4D). These observations thus suggest a role for Mg2+ in mediating ribosome-NC interactions. Of the αSyn charge variants, the most negatively charged variant, K/E6–60, is likely to support such Mg2+-mediated interactions, which may go some way toward rationalizing why this NC gives rise to lower NMR intensities (i.e., interacts with the ribosome more) relative to the K/E6–45 RNC (Fig. 1F).

The Effect of TF on NC Interactions.

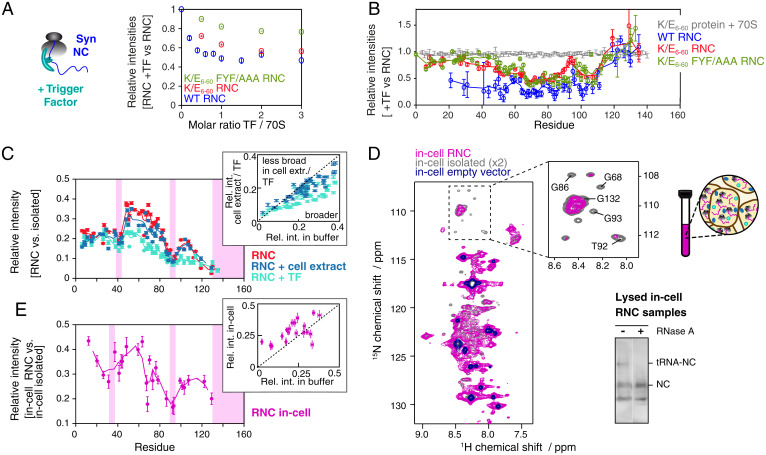

We explored NC handover between the ribosome surface and TF. We previously showed that TF addition to WT αSyn RNCs caused significant nonuniform reductions (10 to 70%) in the intensities of the αSyn cross-peaks (4). When TF was titrated into variant αSyn RNCs, decreases in 1H,15N-correlated NMR intensities were again observed for each αSyn RNC variant (Fig. 5 A and B and SI Appendix, Fig. S5 A and B). For all RNCs, only minimal perturbations are seen for the tunnel-emerged C-terminal region, consistent with about 45 residues from the PTC being necessary to make contact with the TF cradle (4, 22). For each of K/E6–60 RNC, 1–100 K/E6–60, and K/E6–60 FYF/AAA RNC, the perturbations observed were significantly more modest than for WT, indicative of a weaker interaction and consistent with reducing the number of basic and aromatic residues. In the full-length RNCs, the N-terminal regions (residues 1 to 45) appear to show only minor interactions, suggesting that they are located beyond the TF cradle. WT αSyn RNC, which contains the signature residues (basic and aromatic) consistent with previously described TF client features (23), appears to undergo more specific, albeit still very weak, interactions with the molecular chaperone (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Characterization of the structural properties of αSyn RNCs in a cellular context. (A) Variation in the intensity of the 1H,15N-amide signal of 70S and WT, K/E6–60, and K/E6–60 FYF/AAA αSyn RNCs as a function of the molar ratio of TF to ribosome. (B) Relative cross-peak intensities of the WT (blue), K/E6–60 (red), and K/E6–60 FYF/AAA (green) αSyn RNCs, as well as K/E6–60 protein (with ribosomes) in the presence of 1 mol equivalent TF vs. in the absence of TF (700 MHz, 277 K). Five-point moving averages are plotted. (C) Cross-peak intensities of αSyn K/E6–60 RNC in buffer (red), in 12.5 g/L cell extract (blue), with TF (cyan) relative to isolated αSyn K/E6–60 protein in the presence of 70S, in the presence of cell extract, and in the presence of 70S and TF, respectively. The sites of the strongest broadenings are indicated by pink shadings. The inset shows the correlation between relative cross-peak intensities (RNC relative to protein) in buffer and cell extract (blue) or TF (cyan). (D) 1H,15N-SOFAST-HMQC of E. coli cells expressed with 2H,15N-labeled arrest-enhanced αSyn K/E6–60 RNC (magenta), αSyn K/E6–60 protein (gray), and an empty vector (dark blue) (800 MHz, 298 K). Cross-peaks corresponding to in-cell background species are observed in the latter spectrum. Selected αSyn resonances displaying significant line broadening within the glycine region of the in-cell RNC are indicated in the inset. (Bottom Right) Anti-αSyn Western blot detecting the RNC species after NMR data acquisition and lysis of the in-cell NMR samples. The NC remained >40% bound to the ribosome after NMR data acquisition, although the disruptive nature of cell lysis procedures used to obtain this value imply that the attachment levels are likely to be significantly higher with the depicted in-cell NMR spectrum. (E) Cross-peak intensities of in-cell αSyn K/E6–60 RNC relative to in-cell αSyn K/E6–60 protein. The sites of the strongest broadenings are indicated. Inset shows correlation between relative cross-peak intensities (RNC versus protein) in buffer and in cell. Data are normalized according to αSyn concentration.

Nature of NC Interactions within Live Cells.

We examined the impact of a cytosolic environment on observable NC interactions by titrating purified E. coli cell extract (24) into samples of K/E6–60 αSyn RNC. The RNCs remained largely intact (Fig. 5C and SI Appendix, Fig. S5E) in the viscous solution (∼14 mg/mL RNC in 12.5 to 37.5 mg/mL cell extract) and gave rise to well-resolved resonances without significant chemical shift perturbations (<0.06 ppm) with progressive resonance broadening ranging from 30 to 50% seen for the majority of cross-peaks (SI Appendix, Fig. S5 F and G). The relative intensities were overall similar to those observed for RNCs in aqueous buffer and in the presence of TF but with subtle differences mostly localizing to the NAC region (Fig. 5C). These data show that TF exerts a specific effect on the NC that is distinct to the general crowding that is seen in cell extract.

Next, we studied actively translating K/E6–60 αSyn RNCs within live E. coli cells to examine the influence of a native cellular environment. Excellent quality NMR spectra of isolated WT αSyn have previously been obtained in both E. coli (25, 26) and mammalian cells (27, 28). Here, we produced an in-cell sample of uniformly 2H,15N-labeled K/E6–60 αSyn RNC using an optimized, arrest-enhanced variant of the SecM stalling motif to retain RNCs during real-time translation and improve the NC signal (SI Appendix, Fig. S5 I and J). We recorded 1H,15N-SOFAST-HMQC spectra (Fig. 5D) and interleaved these with one-dimensional (1D) 1H,15N-diffusion measurements (SI Appendix, Fig. S5K) to monitor cell leakage and ensure observation of exclusively intracellular species (25). The in-cell sample of K/E6–60 αSyn RNC gave rise to resolvable resonances (Fig. 5D) that could unambiguously be attributed to K/E6–60 αSyn (with chemical shift perturbations <0.06 ppm). Additionally, significantly sharper cross-peaks with higher signal intensity were also observed, overlaying closely with those obtained from an in-cell sample transformed with an empty vector. These signals arise due to the presence of high (millimolar) concentrations of small molecules such as metabolites, peptides, or free amino acids present in E. coli (29) and contrast against the significantly lower concentration of intracellular RNC (∼30 μM, SI Appendix, Fig. S5H).

To further ascertain that the observed cross-peaks originate from RNCs rather than released in-cell species, we produced an in-cell NMR sample of isolated K/E6–60 αSyn using identical expression conditions, and we compared the signal intensities of 29 well-resolved resonances in the in-cell RNC sample (Fig. 5E). We found significant variations in residue-specific signal attenuation that were significantly more pronounced than those observed for the in-cell RNC sample with a WT SecM sequence (whose weaker stalling motif results in more released NC species) (SI Appendix, Fig. S5 I and J), suggesting the detection of a significant population of intracellular, ribosome-bound K/E6–60 αSyn NCs. The in-cell RNC spectra show reasonably similar broadening patterns as those seen for αSyn K/E6–60 RNC in buffer, TF, and cell extract (Fig. 5 C and E, Insets). Moreover, broadened resonances were also localized to the regions around residue F94 and, to a lesser extent, around residue Y39, with the most extensive line broadenings observed at the C terminus of αSyn. NMR line broadening of released αSyn protein has been observed within both bacterial (26) and mammalian cells (27), and while it is therefore likely that some of the line broadenings observed here are caused by combination of macromolecular crowding and direct interactions with components of the cell, the NC resonance intensities reported here are relative to those of the isolated protein under identical conditions and should therefore significantly account for these effects. Moreover, the ribosome accounts for circa 30% of E. coli cellular mass and has been shown to dominate quinary interactions in several isolated protein in-cell studies (30), which are thought to have a potential regulatory role in modulating protein activity (31). These considerations, together with the very high local NC-ribosome concentrations experienced (6), support the notion that the line broadenings observed here are predominantly a result of ribosome interactions, in a manner similar to that observed in vitro: the NC-ribosome interactions likely persist in vivo.

Discussion

We have exploited the disordered nature of αSyn to investigate the sequence determinants of ribosome-NC interactions in the absence of complex folding events. NMR spectroscopy is uniquely able to describe such dynamics in exquisite detail, and through the use of RDC-restrained MD calculations, we have been able to describe some of the conformational preferences of a nascent polypeptide chain. In particular, we examined the impact of the ribosome surface on chain elongation and described how its conformational landscape is perturbed by the crowded, cytosolic environment into which it enters.

We expect that these observations will guide our understanding of the ubiquitous process by which all NCs explore their conformational landscape (32) in order to find their native states as the elongation process proceeds.

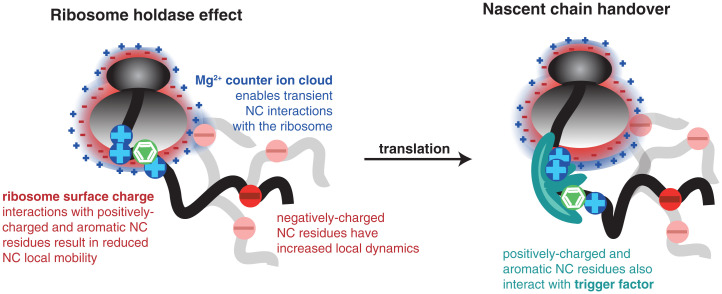

In the case of αSyn, the positively charged lysine residues within the N-terminal amphipathic region are attracted to the negatively charged ribosome surface, and systematic charge alterations of the αSyn NC rescue much of the signal broadening observed in NMR spectra as a result of local interactions. However, even αSyn NCs devoid of basic residues in the amphipathic region still experience motional restrictions at their N terminus, suggesting additional factors at play other than electrostatic interactions, as also observed for intrinsically disordered PIR NCs (33). We show that aromatic residues can create contacts with the ribosome, which is also a feature seen for an unfolded immunoglobulin NC (13). As aromatic residues in part drive hydrophobic collapse during folding and typically become buried within globular folds, the interactions described between aromatic residues and the ribosome surface suggest a mechanism for the latter to specifically sequester disordered states. Although not a common interaction, base stacking between RNA and aromatic ring side chains has been described (34), and it may be possible that a similar mechanism occurs with rRNA. Use of RDC-restrained MD calculations additionally permitted the dissection of the K/E6–60 NC and its ribosomal interactions. Despite exhibiting a highly dynamic ensemble, this NC emerges from the tunnel with a preferred directionality toward the protein-rich side of the ribosome surface at the exit port, close to the TF binding site, and in which Mg2+ ions contribute a role toward stabilizing contacts between the ribosome and negatively charged NC residues.

Our study reveals that the signature interaction motifs of molecular chaperones, including TF (23, 35) and DnaK (36), as well as of other ribosome-associated cellular factors (37) (i.e., both basic and aromatic residues) are also those mediating interactions with the ribosome surface. The NMR measurements of TF interactions with αSyn NCs in purified RNCs indicate that removal of basic and aromatic residues causes a reduction of interaction between TF and the NC. The NMR line broadenings observed here within αSyn RNCs show high similarity with the intensity profiles observed in αSyn in the presence of other chaperone systems such as HSC70 and Hsp90, with a pattern that reflects the canonical chaperone recognition motif (28) in αSyn. These observations support the notion that the ribosome itself might have a chaperoning role akin to a holdase and can hand over NC substrates to its auxiliary partners during synthesis (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

The ribosome surface acts as a molecular chaperone. Positively charged and aromatic residues within the NC interact with the highly negatively charged ribosome surface. Negatively charged regions create a repulsion with the ribosome surface and are highly dynamic. In some cases, negatively charged residues are seen to interact with the negatively charged ribosome surface via the Mg2+ ion shell surrounding the ribosome. The molecular chaperone, TF, also preferentially interacts with positively charged and aromatic residues within the NC. A handover from the ribosome surface to the molecular chaperone is likely to occur during NC elongation.

Within live E. coli cells, our NMR spectrum of the ribosome-bound αSyn NC remains closely similar to that of the RNC observed in reconstituted cytosol and that in vitro, suggesting little influence of the cellular structures or lipid membranes. We note that the patterns of NMR line broadenings identified in vitro have also been similarly observed for the released mature αSyn protein within bacterial (26) and mammalian cells (27); with the ribosome accounting for up to ∼37% in mass in rapidly dividing E. coli, interactions between the αSyn protein and ribosomes are likely to be at the origin of these effects. Moreover, with the aromatic residues F4 and Y39 also known to initiate lipid membrane interactions, and F4 in particular having a role in nucleating helix formation within the membrane (38), it is tempting to speculate an interplay between the handover from ribosome to chaperones and regulation of membrane association of αSyn.

Our data also reveal the ability to study RNCs in live cells, and that, at ∼2.3 MDa, is well beyond the molecular weight of any other system studied by in-cell NMR spectroscopy to date (39). We believe that these first direct structural observations of RNCs in cell will facilitate future investigations of cotranslational protein folding under increasingly more physiologically relevant conditions.

In conclusion, we have identified the sequence motifs that trigger the activity of the ribosome as a molecular chaperone that regulates the conformational properties of NCs. Our recent findings that ascribe a specific role to the ribosome in protecting aggregation prone nascent polypeptides from the competing misfolding processes (40) suggest that the molecular characterizations of ribosome interaction modes described here could be useful in the future in understanding disease-related processes.

Materials and Methods

Protein and RNC Production.

Site-directed mutagenesis was used to generate all modified αSyn constructs. Isolated proteins were expressed using uniform 15N or 15N,13C-labeling in BL21(DE3) E. coli cells and purified using standard procedures (41), with yields (∼14 mg/L) and purity (>95%) comparable to those of WT αSyn. TF was prepared from BL21(DE3) E. coli using nickel affinity chromatography followed by Tobacco Etch Virus (TEV) protease cleavage of the hexa-histidine tag and size exclusion chromatography as described previously (4). Uniformly 15N-labeled RNCs were generated in BL21(DE3) E. coli cells as described previously (14) with an additional TEV protease cleavage step to remove the H6-tag (4). NMR measurements were performed in Tico buffer (10 mM Hepes, 30 mM NH4Cl, 12 mM MgCl2, 5 mM EDTA, 0.1% protease inhibitors, SigmaFast), pH 7.0 (14).

Pf1 Phage and RNC Preparation for RDC Measurements.

Bacteriophage Pf1 (ASLA Biotech Ltd.) was centrifuged at 95,000 rpm for 1 h at 5 °C in a Beckman TLA-110 rotor and resuspended in Tico buffer. This procedure was repeated twice. The phage concentration was determined from the ultraviolet absorbance at 270 nm (ε = 2.25 mg ⋅ mL−1 ⋅ cm−1). The deuterium splitting was measured from the 1D 2H NMR spectrum to confirm the concentration of phage in the NMR sample and to verify the homogeneity of the aligned liquid-crystal phase (SI Appendix, Fig. S3A). Anisotropic RNC samples were initially recorded in the absence of phage to check sample integrity via 15N X-STE diffusion, then concentrated and mixed with phage.

Determination of RNC Integrity and NC Occupancy.

As described previously (14), the RNC sample integrity was determined using Western blots detecting the intact tRNA-bound form of NCs, and the NC occupancy was determined based upon a standard curve from isolated αSyn protein standards of known concentration using Western blots.

NMR Spectroscopy of RNCs.

All NMR data were acquired at 277 K, 700 MHz using a Bruker Avance III spectrometer (UCL) except for the RDC measurements, recorded at 277 K on a 950 MHz Bruker Avance III HD spectrometer (NMR Centre, Crick Institute), and the in-cell NMR measurements, recorded at 298 K on an 800 MHz Bruker Avance III spectrometer (UCL). All spectrometers were equipped with a TXI cryoprobe.

1H,15N-SOFAST-HMQC spectra (42) were recorded using nonuniform weighted sampling (43) with 1,024 complex points and a sweep width of 10,504 Hz in the 1H dimension, 122 complex points and a sweep width of 1,845 Hz in the 15N dimension, and a recycle time of 50 ms. 15N-edited X-STE diffusion measurements (44) were recorded using a diffusion delay of 100 ms, and bipolar trapezoidal gradient encoding pulses of a total length of 4 ms and strengths corresponding to 5% and 95% of the maximum gradient strength (0.56 Tm−1).

For RDC measurements, 15N-HSQC spectra were recorded using gradient coherence-order-selection and sensitivity enhancement (45, 46). 15N-TROSY-HSQC spectra were recorded using the Nietlispach TROSY implementation (47, 48), modified to incorporate band-selective Ha/Hb decoupling [using an IBurp1 shaped pulse (49), and centered at 3 ppm with a bandwidth (50% inversion) of 4.9 ppm (1,500 μs pulse length at 700 MHz)] during t1 (50), with a temperature compensation block during the recycle delay to match the 15N radio frequency power deposition with that of the 15N HSQC. In both experiments, water was preserved along the +z axis with a combination of water flip-back pulses and weak bipolar gradients during t1.

The backbone assignment spectra of αSyn K/E6–60 [HSQC, HNCO, HN(CA)CO, HN(CO)CACB, and intra-HNCACB spectra] were acquired using the band-selective excitation short-transient technique, modified to allow long 15N acquisition times by incorporation of semiconstant-time 15N chemical shift evolution. The 13C chemical shift evolution in the CACB-type experiments was implemented in a constant-time fashion. The data were recorded with nonuniform sampling in Topspin3 (typical fractional sampling ratios: 5 to 15%) and using the online schedule generator available at gwagner.med.harvard.edu/intranet/hmsIST/. The assignments have been deposited under Biological Magnetic Resonance Bank accession number 51049.

For in-cell samples, SOFAST-HMQC experiments were acquired with 256 complex points and a sweep width of 26 ppm in the indirect dimension and 1,024 complex points and a sweep width of 15 ppm in the direct dimension, corresponding to an acquisition time of ∼50 ms. To monitor cell leakage, 1D 15N SORDID diffusion experiments were interleaved between SOFAST-HMQC experiments and acquired with a diffusion delay of 300 ms, using gradient pulses of 4 ms and gradient strengths corresponding to 5% and 95% of the maximum gradient strength (0.56 Tm−1). No discernible changes were observed between in-cell spectra acquired during the course of NMR data acquisition. The NMR protocols used are described in detail in SI Appendix.

NMR Data Processing.

NMR data were processed and analyzed by NMRPipe (51), Sparky and CcpNmr (52) software packages, and the Azara package for RDCs (Azara v2.8).

Cross-peak intensities of the αSyn RNCs were reported relative to the corresponding isolated αSyn variant in the presence of an equimolar concentration of 70S ribosomes (recorded at 5 µM) (Fig. 1 F and G). The NC concentration was determined as described previously (14). For each residue, the relative intensities were calculated as

where INC/iso is the intensity of the NC/isolated protein, c is its concentration, and NS is the number of scans within the summed up two-dimensional (2D) 1H,15N correlation SOFAST-HMQC spectra. SEs were derived from the spectral noise and using standard propagation methods. In Fig. 5, the analogous strategy was applied to derive relative intensities in the presence versus in the absence of TF (Fig. 5B) or in cell (Fig. 5 C and E). In Fig. 2, absolute intensities of the full-length K/E6–60 RNC and its truncated version K/E6–60 1–100 RNC were plotted (as normalized by their concentration and number of scans).

For the RDC work, signal-to-noise ratios were calculated as the ratio of the peak height to the SD of the data points within a signal-free region. Linewidths were measured in CcpNmr Analysis. The uncertainties in peak positions depend on the accuracy of the peak-picking, which in turn depends on the signal-to-noise ratio and linewidth of the peaks. An empirical relationship between the peak position and the signal-to-noise ratio and peak linewidth was derived using a large set of simulated peaks with varying signal-to-noise ratios and linewidths:

| [1] |

where is the uncertainty of the peak position in hertz, is the linewidth (in hertz) and the is the signal-to-noise ratio. The RDC is calculated from four peak positions,

| [2] |

and hence the corresponding uncertainty (substituting Eq. 1 for each of the terms) is given by

Building the RNC Model.

The starting atomic model of the K/E6–60 αSyn RNC was built based on the structure obtained from MD flexible fitting (53) of the cryo-electron microscopy map of the SecM-stalled E. coli ribosome (54). The N terminus of the original structure of the SecM was extended with the K/E6–60 αSyn sequence using Swiss-PDB Viewer (55). Only the atoms surrounding the exit tunnel (within 25 Å from the NC) were used, as well as the region of the ribosome surface, which is accessible to the NC as determined from our previous coarse-grained study (4). Ribosome atoms were kept fixed during the simulation apart from those within the flexible loops and disordered tails of ribosomal proteins that line the exit tunnel and the ribosome surface.

MD Simulations.

MD simulations were performed in the AMBER03w force field (56) with the four-site TIP4P/2005 water model (57) successfully used in previous IDP simulations (58, 59). The simulation box consisted of 2,103,176 atoms, including 1 Cl− and 648 Mg2+ ions to neutralize the system. RDCs were applied as ensemble averaged structural restraints using the tensor-free Θ method (60). Simulations were run in GROMACS 5.0.4 (61) with Plumed 2.1 (62) libraries used to introduce RDC restraints and well-tempered bias-exchange metadynamics protocols. Bias was exchanged between six replicas, each sampling different CVs: three AlphaBeta CVs (applied to backbone angles and to angles χ1 and χ2 for hydrophobic and polar amino acids to enhance the side-chain packing search), AlphaRMSD (to evaluate α-helicity within the NC), and two Coordination Number CVs (measuring the number of hydrophobic contacts within the NC and the contacts between the NC and the ribosome surface). Electrostatic interactions above a cutoff of 0.9 nm were treated with the particle-mesh Ewald method (63), whereas for Lennard-Jones interactions, a 1.2 nm cutoff was used. Bond lengths were constrained with the LINCS algorithm (64), and the time step for the simulation was set to 2.0 fs. Exchange between replicas was attempted every 10 ps according to a replica-exchange scheme and well-tempered scheme (18), with a bias factor of 10 to rescale the added bias potential. The convergence of the simulation was assessed based on the free energy profiles calculated for each CV as an average over the last 100 ns of simulations (SI Appendix, Fig. S4A).

Trajectory Analysis.

The analysis of the metadynamics trajectory and the assignment of microstates was carried out in VMD software (65) using the METAGUI plugin (66) and Plumed 2.1 (62). The sketch-map algorithm (20) was used to generate low-dimensional representations of the MD trajectory described in the dihedral angle space. The obtained sketch-map coordinates were used to plot the 2D free energy landscape. Interactions between the NC and the ribosome were calculated from the trajectory using MDAnalysis python library (67) and represented using a circular plot generated with Circos (68). Chemical shifts were back-calculated using the ChemShift method (69). All other structural properties from the MD ensemble were calculated in VMD or using Python and the MDAnalysis library.

In-Cell NMR Samples.

Cell cultures of 2H,15N-labeled RNCs and isolated αSyn K/E6–60 (without His6 and TEV cleavage site) were produced using the high cell density growths as described for purified samples and in which the cells were progressively adapted into deuterated isotopes. After harvesting, the cell pellet was washed twice, each time by gently resuspending in in-cell NMR buffer (75 mM bis Tris propane, 75 mM Hepes, 25 mM MgCl2, pH 7.5) followed by centrifugation. The resulting pellet was resuspended as a 40% (wt/vol) slurry in in-cell NMR buffer, 10% (vol/vol) D2O, and 0.01% (vol/vol) DSS. Cell viability was monitored by plating colony tests, with no discernible difference between the NMR sample at the start and end of data acquisition. To minimize the population of intracellular, ribosome-released species, an arrest-enhanced stalling motif [based on SecM deriving from Mannheimia succiniciproducens (70)] was used for in-cell NMR measurements.

Preparation of Reconstituted Cytosol.

Lyophilized E. coli lysate was prepared based upon a previous protocol (71). A starter culture of BL21(DE3) cells in LB was used to inoculate 500 mL of MDG media (50 mM NH4Cl, 25 mM Na2HPO4, 5 mM Na2SO3, 4 g/L glucose, 2 g/L L-aspartic acid, pH 7.0, 2 mM MgSO4, 0.2% trace metals [100% trace metals: 50 mM FeCl2 (dissolved in 0.1 M HCl), 20 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MnCl2, 1 mM ZnSO4, 2 mM CoCl2, 2 mM CuCl2, 2 mM NiCl2, 2 mM Na2MoO4, 2 mM Na2SeO3, 2 mM H3BO3]). The cells were incubated for 18 h at 37 °C and harvested by centrifugation. The cell pellet was washed twice by resuspension in EM9 salts (25 mM Na2HPO4, 25 mM KH2PO4, 50 mM NaCl, pH 8.0) followed by centrifugation (4,000 rpm, 30 min, 4 °C). The cells were then resuspended in EM9 media (EM9 salts supplemented with 2.5 mM MgSO4, 100 μM CaCl, 2 g/L glucose, 0.25% BME vitamins [Sigma], and 0.0125% trace metals) containing isotopes (2 g/L 15NH4Cl) and 1 mM isopropyl ß-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside. After incubating for 10 min at 30 °C, rifampicin was added to 150 μg/L and the cells were incubated for 30 min at 30 °C. Cells were harvested and lysed in Tico buffer by French press, and then the cellular debris was pelleted. The supernatant was filtered (0.22 μm) and then lyophilized. The resulting powder was resuspended into Tico buffer, and the pH was adjusted to 7.0. The mixture was then lyophilized again in single-use aliquots and stored at −80 °C. The mass fraction of protein in the cell extract was determined by bicinchoninic acid assay and found to be 65.4 ± 7.5%, consistent with the protein content of E. coli cells (72).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank B. Bukau (Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg) for the kind gift of the anti-SecM antibody. We acknowledge technical assistance from Philip Lawler and thank Carlo Camilloni (University of Milano) for valuable insights and discussion on MD simulations setup. J.C. and T.W. acknowledge the use of the Advanced Research Computing High End Resource UK National supercomputing service (http://www.archer.ac.uk/). A.D. was supported by the Motor Neurone Disease Association. We acknowledge the use of the University College London Biomolecular NMR Centre. This work was supported by the Francis Crick Institute through provision of access to the Medical Research Council Biomedical NMR Centre. This work was supported by a Wellcome Trust Investigator award (to J.C., 206409/Z/17/Z).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2103015118/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.

References

- 1.Cassaignau A. M. E., Cabrita L. D., Christodoulou J., How does the ribosome fold the proteome? Annu. Rev. Biochem. 89, 389–415 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Voss N. R., Gerstein M., Steitz T. A., Moore P. B., The geometry of the ribosomal polypeptide exit tunnel. J. Mol. Biol. 360, 893–906 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fedyukina D. V., Jennaro T. S., Cavagnero S., Charge segregation and low hydrophobicity are key features of ribosomal proteins from different organisms. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 6740–6750 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deckert A., et al. , Structural characterization of the interaction of α-synuclein nascent chains with the ribosomal surface and trigger factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 5012–5017 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ellis J. P., Bakke C. K., Kirchdoerfer R. N., Jungbauer L. M., Cavagnero S., Chain dynamics of nascent polypeptides emerging from the ribosome. ACS Chem. Biol. 3, 555–566 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cabrita L. D., et al. , A structural ensemble of a ribosome-nascent chain complex during cotranslational protein folding. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 23, 278–285 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaiser C. M., Goldman D. H., Chodera J. D., Tinoco I. Jr., Bustamante C., The ribosome modulates nascent protein folding. Science 334, 1723–1727 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Waudby C. A., et al. , Systematic mapping of free energy landscapes of a growing filamin domain during biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, 9744–9749 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marino J., Buholzer K. J., Zosel F., Nettels D., Schuler B., Charge interactions can dominate coupled folding and binding on the ribosome. Biophys. J. 115, 996–1006 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoffmann A., et al. , Concerted action of the ribosome and the associated chaperone trigger factor confines nascent polypeptide folding. Mol. Cell 48, 63–74 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spillantini M. G., Goedert M., The alpha-synucleinopathies: Parkinson’s disease, dementia with Lewy bodies, and multiple system atrophy. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 920, 16–27 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Waudby C. A., Launay H., Cabrita L. D., Christodoulou J., Protein folding on the ribosome studied using NMR spectroscopy. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 74, 57–75 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cassaignau A., et al. , Interactions between nascent proteins and the ribosome surface inhibit co-translational folding. Nat. Chem., in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cassaignau A. M. E., et al. , A strategy for co-translational folding studies of ribosome-bound nascent chain complexes using NMR spectroscopy. Nat. Protoc. 11, 1492–1507 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang X., et al. , Probing the dynamic stalk region of the ribosome using solution NMR. Sci. Rep. 9, 13528 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sallum C. O., Martel D. M., Fournier R. S., Matousek W. M., Alexandrescu A. T., Sensitivity of NMR residual dipolar couplings to perturbations in folded and denatured staphylococcal nuclease. Biochemistry 44, 6392–6403 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laio A., Parrinello M., Escaping free-energy minima. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 12562–12566 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barducci A., Bussi G., Parrinello M., Well-tempered metadynamics: A smoothly converging and tunable free-energy method. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 020603 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.C. Camilloni, A. Cavalli, M. Vendruscolo, . Replica-averaged metadynamics. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 9, 5610–5617 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ceriotti M., Tribello G. A., Parrinello M., From the cover: Simplifying the representation of complex free-energy landscapes using sketch-map. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 13023–13028 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schuwirth B. S., et al. , Structures of the bacterial ribosome at 3.5 A resolution. Science 310, 827–834 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oh E., et al. , Selective ribosome profiling reveals the cotranslational chaperone action of trigger factor in vivo. Cell 147, 1295–1308 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patzelt H., et al. , Binding specificity of Escherichia coli trigger factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 14244–14249 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sarkar M., Smith A. E., Pielak G. J., Impact of reconstituted cytosol on protein stability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 19342–19347 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Waudby C. A., et al. , Rapid distinction of intracellular and extracellular proteins using NMR diffusion measurements. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 11312–11315 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Waudby C. A., et al. , In-cell NMR characterization of the secondary structure populations of a disordered conformation of α-synuclein within E. coli cells. PLoS One 8, e72286 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Theillet F.-X., et al. , Structural disorder of monomeric α-synuclein persists in mammalian cells. Nature 530, 45–50 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burmann B. M., et al. , Regulation of α-synuclein by chaperones in mammalian cells. Nature 577, 127–132 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Serber Z., Ledwidge R., Miller S. M., Dötsch V., Evaluation of parameters critical to observing proteins inside living Escherichia coli by in-cell NMR spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 8895–8901 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Breindel L., Yu J., Burz D. S., Shekhtman A., Intact ribosomes drive the formation of protein quinary structure. PLoS One 15, e0232015 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DeMott C. M., Majumder S., Burz D. S., Reverdatto S., Shekhtman A., Ribosome mediated quinary interactions modulate in-cell protein activities. Biochemistry 56, 4117–4126 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Waudby C. A., Dobson C. M., Christodoulou J., Nature and regulation of protein folding on the ribosome. Trends Biochem. Sci. 44, 914–926 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Knight A. M., et al. , Electrostatic effect of the ribosomal surface on nascent polypeptide dynamics. ACS Chem. Biol. 8, 1195–1204 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morozova N., Allers J., Myers J., Shamoo Y., Protein-RNA interactions: Exploring binding patterns with a three-dimensional superposition analysis of high resolution structures. Bioinformatics 22, 2746–2752 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tomic S., Johnson A. E., Hartl F. U., Etchells S. A., Exploring the capacity of trigger factor to function as a shield for ribosome bound polypeptide chains. FEBS Lett. 580, 72–76 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rüdiger S., Germeroth L., Schneider-Mergener J., Bukau B., Substrate specificity of the DnaK chaperone determined by screening cellulose-bound peptide libraries. EMBO J. 16, 1501–1507 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schibich D., et al. , Global profiling of SRP interaction with nascent polypeptides. Nature 536, 219–223 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lokappa S. B., et al. , Sequence and membrane determinants of the random coil-helix transition of α-synuclein. J. Mol. Biol. 426, 2130–2144 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Luchinat E., Banci L., A unique tool for cellular structural biology: In-cell NMR. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 3776–3784 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Plessa E., et al. , Nascent chains can form co-translational folding intermediates that promote post-translational folding outcomes in a disease-causing protein. Nat. Commun., in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hoyer W., et al. , Dependence of α-synuclein aggregate morphology on solution conditions. J. Mol. Biol. 322, 383–393 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schanda P., Kupče E., Brutscher B., SOFAST-HMQC experiments for recording two-dimensional heteronuclear correlation spectra of proteins within a few seconds. J. Biomol. NMR 33, 199–211 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Waudby C. A., Christodoulou J., An analysis of NMR sensitivity enhancements obtained using non-uniform weighted sampling, and the application to protein NMR. J. Magn. Reson. 219, 46–52 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ferrage F., Zoonens M., Warschawski D. E., Popot J.-L., Bodenhausen G., Slow diffusion of macromolecular assemblies by a new pulsed field gradient NMR method. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 2541–2545 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bodenhausen G., Ruben D. J., Natural abundance nitrogen-15 NMR by enhanced heteronuclear spectroscopy. Chem. Phys. Lett. 69, 185–189 (1980). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schleucher J., et al. , A general enhancement scheme in heteronuclear multidimensional NMR employing pulsed field gradients. J. Biomol. NMR 4, 301–306 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nietlispach D., Suppression of anti-TROSY lines in a sensitivity enhanced gradient selection TROSY scheme. J. Biomol. NMR 31, 161–166 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pervushin K., Riek R., Wider G., Wüthrich K., Attenuated T2 relaxation by mutual cancellation of dipole-dipole coupling and chemical shift anisotropy indicates an avenue to NMR structures of very large biological macromolecules in solution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 12366–12371 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Geen H., Freeman R., Band-selective radiofrequency pulses. J. Magn. Reson. 93, 93–141 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yao L., Ying J., Bax A., Improved accuracy of 15N-1H scalar and residual dipolar couplings from gradient-enhanced IPAP-HSQC experiments on protonated proteins. J. Biomol. NMR 43, 161–170 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Delaglio F., et al. , NMRPipe: A multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J. Biomol. NMR 6, 277–293 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vranken W. F., et al. , The CCPN data model for NMR spectroscopy: Development of a software pipeline. Proteins 59, 687–696 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gumbart J., Schreiner E., Wilson D. N., Beckmann R., Schulten K., Mechanisms of SecM-mediated stalling in the ribosome. Biophys. J. 103, 331–341 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bhushan S., et al. , SecM-stalled ribosomes adopt an altered geometry at the peptidyl transferase center. PLoS Biol. 9, e1000581 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Guex N., Peitsch M. C., SWISS-MODEL and the Swiss-PdbViewer: An environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis 18, 2714–2723 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Best R. B., Mittal J., Protein simulations with an optimized water model: Cooperative helix formation and temperature-induced unfolded state collapse. J. Phys. Chem. B 114, 14916–14923 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Abascal J. L. F., Vega C., A general purpose model for the condensed phases of water: TIP4P/2005. J. Chem. Phys. 123, 234505 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Knott M., Best R. B., A preformed binding interface in the unbound ensemble of an intrinsically disordered protein: Evidence from molecular simulations. PLOS Comput. Biol. 8, e1002605 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mittal J., Yoo T. H., Georgiou G., Truskett T. M., Structural ensemble of an intrinsically disordered polypeptide. J. Phys. Chem. B 117, 118–124 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Camilloni C., Vendruscolo M., A tensor-free method for the structural and dynamical refinement of proteins using residual dipolar couplings. J. Phys. Chem. B 119, 653–661 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.George Abraham B., et al. , Fluorescent protein based FRET pairs with improved dynamic range for fluorescence lifetime measurements. PLoS One 10, e0134436 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tribello G. A., Bonomi M., Branduardi D., Camilloni C., Bussi G., PLUMED 2: New feathers for an old bird. Comput. Phys. Commun. 185, 604–613 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 63.Essmann U., et al. , A smooth particle mesh Ewald method. J. Chem. Phys. 103, 8577–8593 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hess B., Bekker H., Berendsen H. J. C., Fraaije J. G. E. M., LINCS: A linear constraint solver for molecular simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 18, 1463–1472 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 65.Humphrey W., Dalke A., Schulten K., VMD: Visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 14, 33–38 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Biarnés X., Pietrucci F., Marinelli F., Laio A., METAGUI. A VMD interface for analyzing metadynamics and molecular dynamics simulations. Comput. Phys. Commun. 183, 203–211 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 67.Michaud-Agrawal N., Denning E. J., Woolf T. B., Beckstein O., MDAnalysis: A toolkit for the analysis of molecular dynamics simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 32, 2319–2327 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Krzywinski M., et al. , Circos: An information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res. 19, 1639–1645 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kohlhoff K. J., Robustelli P., Cavalli A., Salvatella X., Vendruscolo M., Fast and accurate predictions of protein NMR chemical shifts from interatomic distances. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 13894–13895 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cymer F., Hedman R., Ismail N., von Heijne G., Exploration of the arrest peptide sequence space reveals arrest-enhanced variants. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 10208–10215 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Smith M. T., Berkheimer S. D., Werner C. J., Bundy B. C., Lyophilized Escherichia coli-based cell-free systems for robust, high-density, long-term storage. Biotechniques 56, 186–193 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pedersen S., Bloch P. L., Reeh S., Neidhardt F. C., Patterns of protein synthesis in E. coli: A catalog of the amount of 140 individual proteins at different growth rates. Cell 14, 179–190 (1978). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.