Significance

Liver accumulation represents a significant barrier in the development of therapeutically efficacious nanoparticle drug delivery systems. Using a series of lipid nanoparticles with distinct organ-targeting properties, we provide evidence for a plausible mechanism of action for nanoparticle delivery to non-liver tissues. Following intravenous injection, specific proteins in the blood are recruited to the nanoparticle’s surface based on its molecular composition and they endow it with a unique biological identity that governs its ultimate fate in the body. An innovative paradigm emerges from this mechanistic understanding of nanoparticle delivery—endogenous targeting—wherein the molecular composition of a nanoparticle is rationally engineered to interact with specific proteins in the blood to overcome liver accumulation and to target specific organs.

Keywords: lipid nanoparticles, mRNA delivery, gene editing, endogenous targeting

Abstract

Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) are a clinically mature technology for the delivery of genetic medicines but have limited therapeutic applications due to liver accumulation. Recently, our laboratory developed selective organ targeting (SORT) nanoparticles that expand the therapeutic applications of genetic medicines by enabling delivery of messenger RNA (mRNA) and gene editing systems to non-liver tissues. SORT nanoparticles include a supplemental SORT molecule whose chemical structure determines the LNP’s tissue-specific activity. To understand how SORT nanoparticles surpass the delivery barrier of liver hepatocyte accumulation, we studied the mechanistic factors which define their organ-targeting properties. We discovered that the chemical nature of the added SORT molecule controlled biodistribution, global/apparent pKa, and serum protein interactions of SORT nanoparticles. Additionally, we provide evidence for an endogenous targeting mechanism whereby organ targeting occurs via 1) desorption of poly(ethylene glycol) lipids from the LNP surface, 2) binding of distinct proteins to the nanoparticle surface because of recognition of exposed SORT molecules, and 3) subsequent interactions between surface-bound proteins and cognate receptors highly expressed in specific tissues. These findings establish a crucial link between the molecular composition of SORT nanoparticles and their unique and precise organ-targeting properties and suggest that the recruitment of specific proteins to a nanoparticle’s surface can enable drug delivery beyond the liver.

Nucleic acids that enable gene silencing (1, 2), expression (3–5), and editing (6–8) possess great potential for use as genetic medicines in multiple clinical settings including cancer (9, 10), inherited genetic disorders (11, 12), and infectious diseases (13–15). Due to the unfavorable pharmacokinetic properties of nucleic acids, viral and nonviral delivery approaches are used to facilitate nucleic acid delivery to target cells (16). Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) represent the most clinically mature nonviral platform for the safe and efficacious delivery of genetic medicines. Indeed, LNPs were an enabling technology for the US Food and Drug Administration approval of the first small interfering RNA (siRNA) drug, Onpattro, in 2018 (17) and the messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines currently being distributed for immunization against the SARS-CoV-2 virus, the causative agent of the COVID-19 pandemic (18, 19). Despite this progress, intravenously (IV) administered LNPs typically accumulate in the liver and are internalized by liver hepatocytes, thereby greatly limiting the scope of their therapeutic applications (20).

Recently, our laboratory overcame this challenge through the discovery of selective organ targeting (SORT), a strategy to rationally design nanoparticles for the extrahepatic delivery of mRNA and gene editing systems following IV administration (Fig. 1A and SI Appendix, Table S1) (21–24). Conventional LNPs are composed of four components: ionizable cationic lipids, amphipathic phospholipids, cholesterol, and poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) lipids (25, 26). We found that augmenting conventional four-component LNPs for mRNA delivery to the liver with a fifth component (termed a SORT molecule) can alter the LNPs’ in vivo organ-targeting properties and lead to the extrahepatic delivery of mRNA. The SORT strategy was generalizable to multiple classes of LNPs and SORT molecules. Lung-, liver-, and spleen-targeting SORT LNPs could deliver diverse cargoes (nucleic acids and proteins) to achieve gene expression and CRISPR/Cas-based gene editing in therapeutically relevant cell types, including epithelial cells, endothelial cells, B cells, T cells, and hepatocytes (21–24). However, the mechanism of action remains undefined. Understanding the mechanism which enables SORT is important for optimizing delivery to currently targetable organs as well as extending the SORT concept to other tissue and cell types. Moreover, mechanistic understanding would establish a biological rationale for overcoming the delivery barrier of liver accumulation that currently hampers IV administered nanoparticles (27).

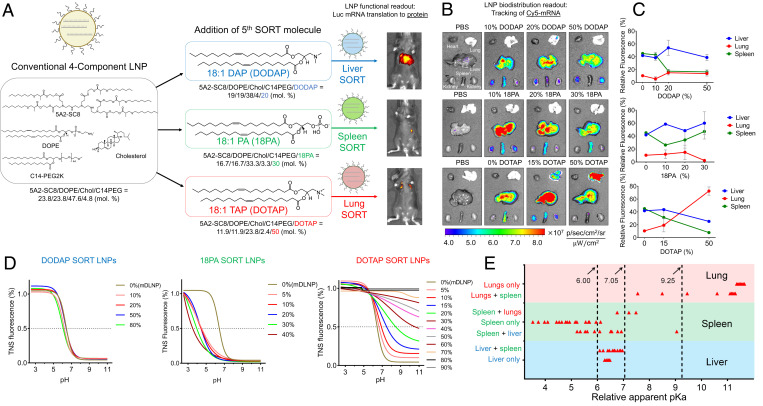

Fig. 1.

SORT nanoparticles for tissue-specific mRNA delivery have unique biodistribution and ionization behavior. (A) By adding a fifth, supplemental SORT molecule to a conventional, four-component LNP (mDLNP: 23.8 mol % 5A2-SC8, 23.8 mol % DOPE, 47.6 mol % cholesterol, and 4.8 mol % C14-PEG2K), the tissue-specific activity of delivered mRNA changes based on the chemical structure of the included SORT molecule. An ionizable cationic lipid (DODAP) enhances liver-specific mRNA translation (liver SORT: 19 mol % 5A2-SC8, 19 mol % DOPE, 38 mol % cholesterol, 4 mol % C14-PEG2K, and 20 mol % DODAP), an anionic lipid (18PA) results in spleen-specific mRNA translation (spleen SORT: 16.7 mol % 5A2-SC8, 16.7 mol % DOPE, 33.3 mol % cholesterol, 3.3 mol % C14-PEG2K, and 30 mol % 18PA), and a cationic quaternary ammonium lipid (DOTAP) results in lung-specific mRNA translation (lung SORT: 11.9 mol % 5A2-SC8, 11.9 mol % DOPE, 23.8 mol % cholesterol, 2.4 mol % C14-PEG2K, and 50 mol % DOTAP). (B) Ex vivo fluorescence of Cy5-labeled mRNA in major organs extracted from C57BL/6 mice IV injected with SORT LNPs that incorporate increasing percentages of different SORT molecules (0.5 mg/kg mRNA/body weight, 6 h). (C) Relative average Cy5 fluorescence measured in the liver, lung, and spleen as a function of SORT molecule percent inclusion (0.5 mg/kg mRNA/body weight, n = 2). SORT molecules promote mRNA biodistribution to target organs. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. (D) Representative TNS assay curves for determining the apparent pKa of SORT LNPs incorporating increasing percentages of ionizable cationic, anionic, or permanently cationic lipid SORT molecules. Apparent pKa was defined as the point at which 50% of TNS fluorescence was achieved. (E) LNPs were assigned a tissue specificity index based on the tissues in which functional luciferase mRNA was detected. Intermediate tissue specificity indexes represent LNPs in which mRNA activity was detected in multiple organs; these LNPs are plotted in the region of the organ for which higher activity was measured. For the 67 LNPs tested with the TNS assay, LNP apparent pKa was correlated with the specificity of luciferase mRNA tissue delivery.

Herein, we identify and study mechanistic factors which could explain the organ-targeting properties of SORT LNPs based on three established principles that define the efficacy of liver-targeting LNPs: biodistribution to the liver, an acid dissociation constant (pKa) near 6.4, and the adsorption of apolipoprotein E (ApoE) to the LNP surface (12, 28). We discovered that each of these three factors (organ level biodistribution, apparent pKa, and serum protein adsorption) are distinct for SORT LNPs and correlate with their tissue-targeting properties. Furthermore, we provide evidence of a three-step mechanism for the functional role of serum protein adsorption on tissue targeting that extends the scope and application of the endogenous targeting mechanism defined for four-component LNP delivery to liver hepatocytes (12, 28). First, desorption of PEG lipids on the LNP surface exposes underlying SORT molecules in the LNP. Next, distinct serum proteins recognize the exposed SORT molecules and adsorb to the LNP surface. Finally, surface-adsorbed proteins interact with cognate receptors expressed by cells in the target organs to facilitate functional mRNA delivery to those tissues.

The results indicate that the choice of SORT molecule governs which proteins most avidly adsorb to the LNP surface, impacting the ultimate biological fate of the LNP (29). We envision that this mechanistic understanding of SORT LNPs will enable their optimization for therapeutic applications in the lung, liver, and spleen and lay the foundation for extending the SORT platform to additional nanoparticle types, physiological tissues, and cell types. Furthermore, our findings suggest that endogenous targeting—that is, tuning a nanoparticle’s molecular composition such that it binds specific proteins in the serum to enable delivery to the target site—could be a generally useful strategy for engineering a wide array of nanomaterials capable of extrahepatic delivery.

Results

SORT Molecules Alter LNP Biodistribution.

mRNA therapeutics must overcome multiple barriers for intracellular delivery, as they do not readily diffuse through anionic cellular membranes and are susceptible to degradation by ribonucleases (RNases) in the blood (5). Ideally, LNPs will encapsulate and protect mRNA from enzymatic degradation, enable accumulation in the target organ, facilitate receptor-mediated endocytosis into cells, and release mRNA from endosomes into the cytosol to undergo translation into a functional protein (12). Through the development of SORT LNPs, we showed that the chemical identity and amount of SORT molecule added to a four-component LNP systematically alters tissue-specific protein expression following mRNA delivery (21). The inclusion of ionizable cationic lipids enhanced liver targeting, anionic lipids resulted in retargeting of delivery to the spleen, and permanently cationic lipids bearing a quaternary ammonium headgroup retargeted delivery to the lungs (Fig. 1A and SI Appendix, Table S1) (21). These experiments revealed how the choice of SORT molecule served as a design parameter to predictably dictate where mRNA would be translated to functional proteins in vivo (21) but did not elucidate the organs where SORT LNPs accumulated and the mechanism of how SORT molecules function. Biodistribution to the target organ should, in principle, be a requisite step for targeted delivery.

Therefore, we first investigated the biodistribution of mRNA encapsulated in SORT LNPs to determine if there was a correlation between the organs in which SORT LNPs accumulated and their tissue-specific mRNA activity. We formulated liver, lung, and spleen SORT LNPs as well as a representative four-component dendrimer LNP for mRNA delivery to the liver (mDLNP) (SI Appendix, Tables S1 and S7) to encapsulate Cy5-labeled mRNA following the identical protocols and formulation parameters used in our previous publications (11, 21). We administered each LNP IV to C57BL/6 mice and tracked the in vivo biodistribution of the Cy5 mRNA using fluorescence imaging. The organs were excised and imaged ex vivo 6 h postinjection (Fig. 1B). The average fluorescence produced by the liver, spleen, and lungs was quantified (Fig. 1C). The incorporation of the ionizable cationic lipid 1,2-dioleoyl-3-dimethylammonium-propane (DODAP) to mDLNP resulted in an increase in average Cy5 mRNA signal in the liver and a decrease of average Cy5 mRNA signal in the spleen, with optimal liver biodistribution at 20% inclusion of DODAP (Fig. 1 B and C). Meanwhile, increasing the percentage of anionic SORT molecule 18PA added to the LNP increased average Cy5 mRNA signal in the spleen (Fig. 1 B and C). Similarly, as the permanently cationic SORT molecule 1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane (DOTAP) was included in the LNP in increasing proportions, there was a progressive increase in Cy5 mRNA signal in the lungs (Fig. 1 B and C). Importantly, these tracking studies quantify where the SORT LNPs biodistribute but not where mRNA is translated to protein (functional delivery). These studies demonstrate that inclusion of a SORT molecule in mDLNP facilitates mRNA biodistribution to the target organ but is not sufficient to explain tissue-specific mRNA activity.

SORT Molecules Alter Apparent LNP pKa.

It is established that global/apparent pKa plays an important role in determining the potency of RNA delivery by LNPs. Indeed, siRNA delivery to liver hepatocytes strongly depends on LNP pKa, with a pKa of 6.2 to 6.4 being optimal for gene silencing; LNPs with a pKa outside of that narrow range were unable to functionally deliver siRNA to the liver (30). Based on the link between pKa and cellular delivery, we analyzed the apparent pKa of 67 different SORT LNPs (SI Appendix, Table S2), all of which were efficacious for tissue-specific mRNA delivery in vivo (21), using the 6-(p-toluidino)-2-naphthalenesulfonic acid (TNS) assay (Fig. 1 D and E and SI Appendix, Figs. S2 and S3). Because SORT involves the inclusion of additional charged lipids, the resulting TNS titration curves capture the ionization behavior of more complex mixed species LNPs. As the lower limit TNS fluorescence of 0% was not measured for some SORT LNPs over the pH range of buffers used in the TNS assay, we defined the apparent pKa as the pH at which 50% normalized TNS fluorescence signal is measured (Fig. 1D).

When plotting relative pKa with respect to tissue-specific activity, SORT LNPs grouped into defined ranges based on their organ-targeting properties (Fig. 1E). Confirming the literature precedent, all liver-targeting SORT LNPs had an apparent pKa within the well-established 6 to 7 range (30) (Fig. 1E). Surprisingly, all lung-targeting SORT LNPs had a higher apparent pKa (greater than 9) (Fig. 1E), while spleen-targeting LNPs had a lower pKa between 2 and 6 (Fig. 1E). This result contrasts with the dogma for conventional LNP delivery to the liver and contributes to the understanding of why SORT LNPs are unconventional and can enable extrahepatic delivery. It is important to note that the SORT LNPs tested here possess a similar, near neutral zeta potential surface charge (SI Appendix, Table S1). Thus, the addition of a SORT molecule to a multicomponent LNP alters its overall pKa that directly relates to the organ-targeting properties of the LNP.

PEG Lipid Desorption Contributes to Effective mRNA Delivery In Vivo.

Conventional four-component LNPs are known to enable functional RNA delivery into liver hepatocytes via an endogenous mechanism in which the desorption of PEG lipids from the LNP surface enables ApoE to bind the LNP; this subsequently enables receptor-mediated binding and uptake of the LNPs by the low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDL-R) (12). We hypothesized that SORT LNPs might operate by a similar mechanism in which 1) PEG lipid desorbs from the LNP to expose underlying SORT molecules, 2) distinct serum proteins recognize the exposed SORT molecules and adsorb to the LNP surface, and 3) these surface-adsorbed proteins interact with cognate receptors which mediate uptake of the LNPs by cells in target tissues (Fig. 2A). First, we established the role of the PEG–lipid component on mRNA delivery efficacy in vivo. LNPs incorporate a PEG lipid on the surface to promote colloidal stability (26). Because the PEG–lipid molecules are noncovalently incorporated into the LNP, they spontaneously desorb at a rate inversely proportional to the length of the PEG lipid’s hydrophobic anchor (31, 32). PEG lipids on the LNP surface can impair serum protein adsorption, resulting in reduced cellular targeting and delivery efficacy (31). The shedding of PEG lipid would be expected to expose the underlying SORT molecules for recognition by serum proteins, promoting their binding of the SORT LNP in the blood.

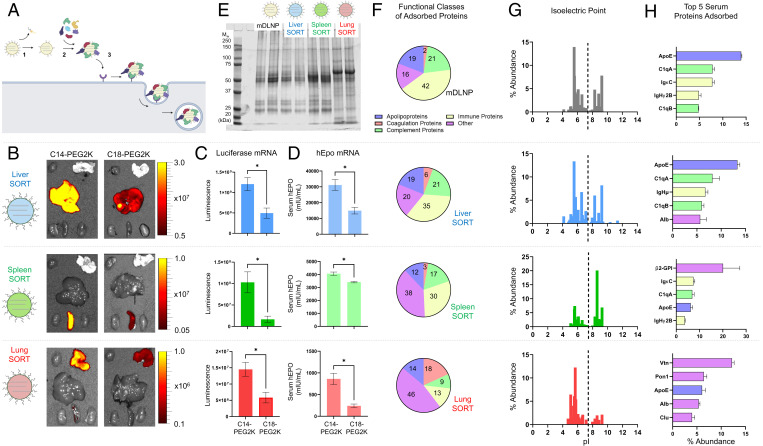

Fig. 2.

Multiple steps are involved in the mechanism of SORT LNP tissue targeting, including formation of unique protein coronas. (A) A proposed three-step endogenous targeting mechanism for tissue-specific mRNA delivery by SORT LNPs in which 1) PEG lipid desorption 2) enables distinct plasma proteins to bind SORT LNPs, 3) resulting in cellular internalization in the target tissues by receptor-mediated uptake. (B) Ex vivo bioluminescence of major organs excised from C57BL/6 mice IV injected with liver, spleen, and lung SORT LNPs incorporating either sheddable PEG lipids (C14-PEG2K) or less sheddable PEG lipids (C18-PEG2K) (0.1 mg FLuc mRNA/kg body weight, 6 h). Total luminescence produced by each organ is reduced when less sheddable PEG lipid is used, suggesting that PEG lipid desorption is a key process for efficacious mRNA delivery by SORT LNPs. (C) Quantification of total luminescence produced by functional protein translated from FLuc mRNA in target organs of C57BL/6 mice IV injected with liver, spleen, and lung SORT LNPs incorporating either C14- or C18-PEG2K (0.1 mg FLuc mRNA/kg body weight, 6 h). (D) ELISA quantification of serum hEPO in C57BL/6 mice treated with liver, spleen, or lung SORT LNPs encapsulating hEPO mRNA (0.1 mg hEPO mRNA/kg body weight, 6 h). Using a less-sheddable PEG reduces SORT LNP potency. (E) SDS–PAGE of the plasma proteins adsorbed to the surface of mDLNP, liver SORT, spleen SORT, and lung SORT LNPs. LNPs with different organ-targeting properties bind distinct plasma proteins. (F) The average abundance of proteins with distinct biological functions in the protein coronas of mDLNP and liver, spleen, and lung SORT LNPs. The choice of SORT molecule leads to large-scale differences in the functional ensemble of plasma proteins which bind the LNP. (G) Isoelectric point distribution for the most enriched proteins which constitute 80% of the protein corona of the LNPs. A SORT molecule’s headgroup structure influences the pI distribution of the protein corona. (H) The top five most abundant plasma proteins that bind different SORT LNPs (n = 3). The chemical structure of SORT molecule affects the number one plasma protein that is most highly enriched on the surface of SORT LNPs. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined using an unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test (*P < 0.05).

To functionally characterize the consequences of PEG lipid desorption on mRNA delivery, we measured the effects of substituting DMG-PEG2000 (C14-PEG2K), a methoxy PEG (mPEG) glyceride with 14-carbon-long alkyl tails, with DSG-PEG2000 (C18-PEG2K), an mPEG glyceride with 18-carbon-long alkyl tails, on the in vivo potency of SORT LNPs. C18-PEG2K is expected to be less sheddable from the LNP compared to C14-PEG2K due to its longer hydrophobic anchor (31, 32). First, we measured the effects of increasing the PEG lipid anchor length on the delivery of luciferase mRNA by injecting C57BL/6 mice IV at a dosage of 0.1 mg/kg mRNA and imaging organ luminescence ex vivo at a timepoint of 6 h postinjection (Fig. 2B). Switching to C18-PEG2K significantly reduced the total luminescence produced by luciferase mRNA translated into a functional protein in target organs when compared to C14-PEG2K for all SORT LNPs (Fig. 2C). To confirm these findings, we delivered human erythropoietin (hEPO) mRNA to target tissues in vivo using liver, spleen, or lung SORT LNPs incorporating either C14-PEG2K or C18-PEG2K. Because hEPO is a secreted protein, delivery efficacy can be readily quantified by measuring hEPO levels in the serum (21). We verified that serum hEPO concentration was lower in mice treated with C18-PEG2K SORT LNPs compared to those treated with C14-PEG2K SORT LNPs (Fig. 2D). Thus, we quantitatively confirmed that SORT LNPs which incorporate a PEG lipid with a longer hydrophobic anchor are less effective for mRNA delivery to target organs. These studies suggest that PEG lipid desorption is a necessary process for efficacious mRNA delivery to target tissues by SORT LNPs.

SORT Molecule Choice Influences LNP–Protein Interactions in the Serum.

The second step of the hypothesized endogenous targeting mechanism for SORT LNPs involves the adsorption of distinct proteins to the LNP surface to form unique protein coronas (Fig. 2A). Following PEG lipid desorption, serum proteins readily adsorb to the surface of IV administered LNPs, forming an interfacial layer known as the “protein corona” that defines their biological identity (29). Adsorption of ApoE has been shown to drive liver targeting of conventional four-component LNPs through binding of the LDL-R highly expressed on hepatocytes (28). Given the strikingly different organ-targeting capabilities of lung and spleen SORT LNPs, we hypothesized that the set of serum proteins that bind the LNPs would be distinct. We isolated the plasma proteins which bind mDLNP, liver SORT, spleen SORT, and lung SORT using differential centrifugation following ex vivo incubation with mouse plasma (33). Treating four-component mDLNP as the base liver-targeting LNP composition, we used sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) (SDS-PAGE) to qualitatively study how the choice of SORT molecule impacted which proteins adsorbed to five-component SORT LNPs (Fig. 2E). While the set of plasma proteins that adsorb to liver SORT looks qualitatively similar to that of mDLNP, the plasma proteins that bind SORT LNPs targeting extrahepatic organs are markedly distinct (Fig. 2E). In particular, a key band is highly enriched for spleen SORT at an Mw of 54 kDa, while a band near 65 kDa is highly enriched for lung SORT (Fig. 2E). Thus, adding a SORT molecule to mDLNP alters the composition of the protein corona in accordance with the SORT molecule’s chemical structure.

Unbiased mass spectrometry proteomics enabled identification and quantification of which proteins bind SORT LNPs in the plasma. We found that over 900 different proteins adsorbed to SORT LNPs, but nearly 98% of these proteins are present at an abundance of less than 0.1%. We anticipate that the most abundant proteins are the ones most likely to be functionally important; thus, we focused our subsequent analysis on the proteins that constitute the majority of the protein corona (80% abundance) for each LNP (SI Appendix, Tables S3–S6). First, we assessed the biological function of these highly abundant proteins. By clustering plasma proteins into the physiological classes of apolipoproteins, coagulation proteins, complement proteins, immune proteins, and other proteins (34), we discovered that the proportion of proteins in each class changed based on the choice of SORT molecule, suggesting that the inclusion of a SORT molecule results in large-scale differences in the ensemble of proteins which bind an LNP (Fig. 2F). The distinct functions of these proteins may play a role in shaping an LNP’s endogenous identity and subsequent fate in vivo.

To better understand what drives these large-scale differences in the functional composition of the protein corona, we studied how a SORT molecule’s chemical structure might affect which proteins bind to LNPs. While each SORT molecule shares a common hydrophobic scaffold that enables the molecule to self-assemble into the LNP, they are distinguished by the chemical structure and charge state of the headgroup. These molecular features may play a role in the differential enrichment of proteins with distinct characteristics, possibly through electrostatic forces which bring specific proteins into proximity of the SORT LNP to facilitate further protein–LNP interactions (34). A protein’s isoelectric point (pI) is defined as the pH at which the protein molecule bears no net charge, providing an estimate of a protein’s charge state in the physiological milieu. We determined the pI of the major proteins that bound mDLNP and each SORT LNP using the bioinformatics resource ExPASy (35). The inclusion of DODAP, an ionizable cationic lipid, to mDLNP did not greatly alter the pI distribution of the major proteins which bound the LNP (Fig. 2G). In contrast, the inclusion of 18PA, a lipid with an anionic headgroup, to mDLNP promoted the adsorption of plasma proteins with a pI greater than physiological pH (Fig. 2G), while the inclusion of DOTAP, a lipid with a cationic quaternary ammonium headgroup, in mDLNP favored the enrichment of proteins with a pI below physiological pH (Fig. 2G). Although all SORT LNPs bound proteins across a broad range of pIs, the nature of the headgroup of a chosen SORT molecule does affect which proteins adsorb to the LNP.

We further analyzed the five most abundant proteins in the protein corona of each LNP. It was discovered that the most highly enriched protein in each protein corona was unique based on the choice of SORT molecule (Fig. 2H). ApoE was the most highly enriched plasma protein for mDLNP, a conventional four-component LNP which targets the liver, on average composing 13.9% of mDLNP’s protein corona (Fig. 2H). This result agrees with the established role of ApoE in RNA delivery to the liver (28), supporting the validity of the experimental approach. Additionally, liver SORT most avidly bound ApoE at an average abundance of 13.3%, representing a 55-fold enrichment compared to native mouse plasma (Fig. 2H). In contrast, spleen SORT was most highly enriched in β2-glycoprotein I (β2-GPI) at an average abundance of 20.1% (125-fold higher than native mouse plasma) (Fig. 2H), while lung SORT was most highly enriched in vitronectin (Vtn) at an average abundance of 12.2% (108-fold higher than native mouse plasma) (Fig. 2H). Thus, SORT LNPs for extrahepatic mRNA most avidly bind proteins distinct from ApoE compared to mDLNP. Furthermore, there were additional distinctions in the top five plasma proteins bound to SORT LNPs in terms of individual molecular species as well as their physiological function (Fig. 2H). To further validate our findings, we examined the protein coronas formed around SORT LNPs in the plasma of an additional mouse strain and identified the same key proteins highly enriched in the protein coronas of SORT LNPs (SI Appendix, Tables S3–S6). Ultimately, SORT LNPs bind low-abundance serum proteins to form unique protein coronas with quantitatively distinct composition based on the nature of the incorporated SORT molecule, which may impact tissue-specific mRNA delivery.

Key Serum Proteins Define SORT LNP Cellular Targeting.

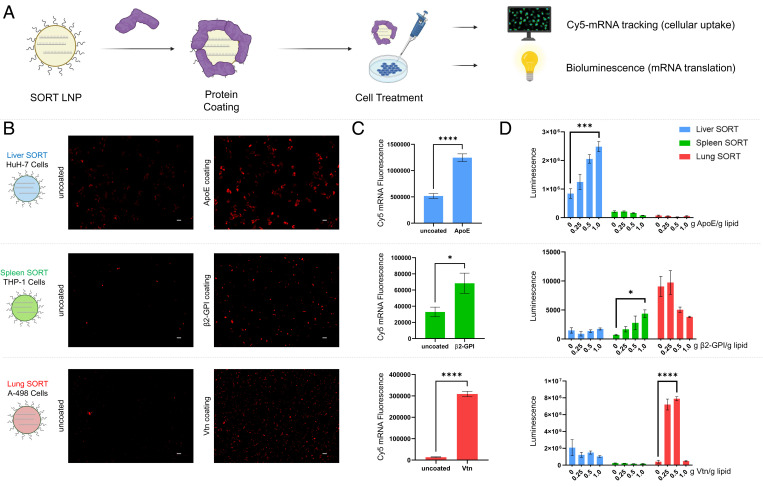

One mechanism by which surface-adsorbed proteins can endogenously target specific tissues is through interactions with cognate cellular receptors, resulting in receptor-mediated endocytosis of the LNP (36) (Fig. 2A). Having identified the serum proteins which most avidly bind SORT LNPs, we functionally characterized how these single proteins affect intracellular delivery of mRNA by SORT LNPs. We incubated all SORT LNPs with either ApoE, β2-GPI, or Vtn, the most highly enriched serum proteins discovered to associate with SORT LNPs in our proteomics studies and measured the effects of these single proteins on LNP uptake and mRNA delivery efficacy in vitro (Fig. 3A). First, we incubated SORT LNPs encapsulating Cy5 mRNA with ApoE and measured cellular uptake in HuH-7 and Hep G2 cells, two cell lines which highly express ApoE’s receptor, LDL-R. Intracellular accumulation of Cy5 mRNA was increased in HuH-7 and Hep G2 cells by a factor of 2.4 (Fig. 3 B and C) and 6.5 (SI Appendix, Fig. S3), respectively, when liver SORT LNPs were incubated with ApoE. Next, we examined THP-1 macrophages, a cell line known to interact with β2-GPI–bound particles containing anionic phospholipids (37), and found that incubation with β2-GPI enhanced Cy5 mRNA uptake of spleen SORT LNPs by a factor of 2.1 (Fig. 3 B and C). Finally, we examined A-498 and U-87 MG cells, which highly express Vtn’s receptor αvβ3 integrin. Incubation with Vtn increased cellular uptake of lung SORT LNPs at a factor of 23.2 (Fig. 3 B and C) and 4.2 (SI Appendix, Fig. S4) times greater than the uncoated LNPs. Thus, the choice of SORT molecule impacts which plasma proteins adsorb to the LNP surface, and these proteins likely interact with cognate receptors expressed by target cells to enhance cellular uptake, promoting intracellular mRNA delivery.

Fig. 3.

Distinct plasma proteins regulate SORT LNP uptake and efficacy in vitro. (A) SORT LNPs were preincubated with either ApoE, β2-GPI, or Vtn prior to treating relevant cell lines to measure cellular uptake (Cy5 mRNA tracking) or functional mRNA delivery (bioluminescence). (B) Representative images of cellular uptake of uncoated and coated SORT LNPs taken up by relevant cell types. Incubating a SORT LNP with the protein most avidly binds increases mRNA uptake in cell lines expressing the cognate receptor (250 ng mRNA per well, 1.5 h). (Scale bar: 50 µm.) (C) Quantification of Cy5 mRNA fluorescence in cells treated with uncoated or coated SORT LNPs (250 ng mRNA per well, 1.5 h, n = 10). Statistical significance was determined using an unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test (****P < 0.0001, *P < 0.05). (D) Activity of functional luciferase protein translated from mRNA delivered by uncoated or protein-coated SORT LNPs in relevant cell lines (25 ng mRNA, 24 h, n = 4). Statistical significance determined using one-way ANOVA with Brown–Forsythe test (****P < 0.0001, ***P < 0.001, *P < 0.05). Individual proteins exclusively bind to specific SORT LNPs and enhance mRNA delivery only to cell lines expressing the cognate receptor. Data are shown as mean ± SEM.

Having determined that key proteins can enhance cellular uptake by distinct receptors, we verified that these proteins improve functional mRNA delivery by measuring the activity of luciferase enzyme translated from mRNA delivered by uncoated and coated SORT LNPs in vitro. Additionally, we aimed to determine whether single protein coatings specifically enhanced the delivery of the individual formulations which most avidly bound those proteins. Cells were treated with liver, spleen, and lung SORT LNPs, encapsulating luciferase mRNA, that were incubated with increasing amounts of ApoE, β2-GPI, or Vtn (Fig. 3D). Luciferase activity was enhanced in HuH-7 and Hep G2 cells by ApoE-coated liver SORT LNPs, whereas luciferase activity in these cells was not improved by spleen or lung SORT LNPs preincubated with ApoE (Fig. 3D and SI Appendix, Fig. S3), suggesting that spleen and lung SORT LNPs do not efficiently bind ApoE and enter LDL-R–expressing cells. Thus, ApoE exclusively enhanced functional mRNA delivery by liver SORT LNPs in LDL-R–expressing cells. Similarly, incubating spleen SORT LNPs with β2-GPI exclusively enhanced functional mRNA delivery to THP-1 macrophages (Fig. 3D), while incubating lung SORT LNPs with Vtn exclusively enhanced functional mRNA delivery to A-498 and U-87 MG cells (Fig. 3D and SI Appendix, Fig. S4). Interestingly, incubating lung SORT LNPs at a ratio of 1.0 g Vtn/g total lipid resulted in diminished luciferase activity, suggesting that excess (free in media) Vtn may be inhibiting αvβ3 integrin to limit mRNA delivery. Collectively, these studies reveal that unique interactions between specific SORT molecules and individual serum proteins selectively promote SORT LNP targeting to distinct cell types by enhancing cellular uptake.

Extrahepatic mRNA Delivery by SORT LNPs Occurs through an ApoE-Independent Mechanism.

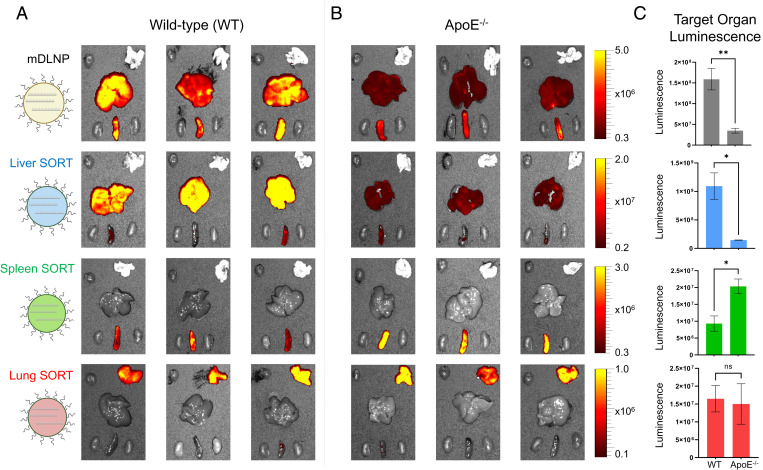

The adsorption of ApoE to the surface of conventional four-component LNPs is a crucial process necessary for highly efficacious RNA delivery to liver hepatocytes (28). mDLNP, which is a four-component LNP for mRNA delivery to the liver, avidly binds to ApoE in the serum. However, the addition of a SORT molecule to mDLNP alters which serum proteins adsorb to the LNP surface. The set of proteins which bind the LNP might play a role in defining the organ-targeting properties of SORT LNPs via an endogenous mechanism whereby surface-adsorbed proteins interact with cognate receptors expressed by cells in the target organ. Since lung and spleen SORT LNPs include molecules (DOTAP and 18PA, respectively) that are not common to conventional LNPs, we reasoned that differences in organ targeting could be driven by differences in protein corona composition. Genetically modified mice can be used to deplete key proteins from the serum, preventing their adsorption to the LNP surface and possibly impairing expected organ targeting. To evaluate the plausibility of an endogenous targeting mechanism in vivo, we investigated how the addition of a SORT molecule to a conventional four-component LNP impacts the functional role of ApoE on tissue-specific mRNA delivery using knockout mice.

We compared the delivery of luciferase mRNA by SORT LNPs to target organs in B6.129P2-Apoetm1Unc/J (ApoE−/−) mice, a genetic knockout model lacking ApoE expression, to wild-type (WT) C57BL/6 mice containing normal levels of ApoE in the serum. Luminescence was quantified to measure functional luciferase mRNA delivery to the target organs of each SORT LNP (Fig. 4). By eliminating ApoE from the serum, mDLNP exhibited significantly reduced mRNA delivery to the liver, with an average reduction of luciferase activity by 78% compared to WT C57BL/6 mice (Fig. 4). Liver SORT LNPs, which also bind ApoE selectively from the serum, maintain this dependence on ApoE for mRNA delivery to the liver: the knockout of ApoE significantly impaired liver targeting, with an average reduction in luciferase activity by 87% compared to WT C57BL/6 mice (Fig. 4). Thus, ApoE is indispensable for efficacious targeting of the liver by both mDLNP and liver SORT LNPs. In stark contrast, mRNA delivery by spleen SORT to the spleen was enhanced by a factor of 2.2 in ApoE−/− mice, suggesting that ApoE plays an antagonistic role in efficacious mRNA delivery to the spleen (Fig. 4). Tissue-specific mRNA delivery by lung SORT LNPs was not significantly different in ApoE−/− mice compared to WT mice, indicating that this serum protein is not functionally important for modulating lung targeting (Fig. 4). Together, these results indicate that mRNA delivery is no longer an ApoE-dependent process upon inclusion of either an anionic lipid or cationic lipid to mDLNP. Rather, spleen SORT and lung SORT LNPs can enable extrahepatic mRNA delivery via an ApoE-independent mechanism. It is plausible that other serum proteins, such as those identified in the proteomics study, may be responsible for endogenous targeting to the spleen and lungs in vivo.

Fig. 4.

Extrahepatic mRNA delivery occurs via an ApoE-independent mechanism. (A) Ex vivo bioluminescence produced by functional protein translated from FLuc mRNA in major organs excised from WT C57BL/6 mice IV injected with mDLNP or liver, spleen, or lung SORT LNPs (0.1 mg/kg FLuc mRNA, 6 h). The role of ApoE on SORT LNP efficacy varies based on the chemical structure of the included SORT molecule. (B) Ex vivo bioluminescence produced by functional protein translated from FLuc mRNA in major organs excised from ApoE−/− mice IV injected with mDLNP or liver, spleen, or lung SORT LNPs (0.1 mg/kg FLuc mRNA, 6 h). (C) Quantification of total bioluminescence produced by target organs excised from WT and ApoE−/− mice treated with mDLNP or liver, spleen, or lung SORT LNPs (0.1 mg/kg FLuc mRNA, 6 h, n = 3). Data are shown as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined using an unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test (**P < 0.01, *P < 0.05, ns, P > 0.05). Elimination of ApoE from the serum using genetic knockout results in a marked reduction of hepatic mRNA delivery by mDLNP and liver SORT LNPs. In contrast, spleen SORT LNPs have enhanced spleen targeting when ApoE is depleted from the serum, while the efficacy of lung SORT LNPs is unaffected by ApoE elimination.

Discussion

Clinical applications of genetic medicines are limited by the availability of efficacious carriers for the intracellular delivery of nucleic acid biomolecules to target tissues. Since IV administered LNPs have been limited to targeting liver hepatocytes to date, there is great need to develop drug delivery systems capable of extrahepatic targeting. Here, we identified mechanistic factors which underly the tissue-targeting properties of SORT LNPs for extrahepatic mRNA delivery. We found that a SORT molecule’s chemical structure uniquely impacts an LNP’s biodistribution, apparent pKa, and serum protein interactions. Furthermore, we provide evidence for a plausible endogenous targeting mechanism involving PEG lipid desorption, serum protein adsorption, and receptor binding followed by cellular uptake to possibly explain the organ-targeting profiles of SORT LNPs (Fig. 2A). Preferential uptake and activity of SORT LNPs likely occurs in the organs which highly express the relevant cellular receptors that favorably interact with serum proteins enriched at the surface of SORT LNPs. Although we cannot rule out additional mechanisms, we have identified multiple key factors which define the organ-targeting properties of SORT LNPs.

The proposed mechanism may have similarity with that of lipoproteins, which can be considered as a natural class of nanoparticles for physiological cholesterol transport through the blood. Acquisition of ApoE in the serum results in uptake of lipoproteins by liver hepatocytes through receptor-mediated endocytosis by LDL-R (38). This physiological function of ApoE is leveraged by DLin-MC3-DMA LNPs for siRNA delivery to the liver; by binding ApoE in the serum, these nanoparticles can endogenously target LDL-R highly expressed by liver hepatocytes (12, 28). The hypothesized mechanism we provide evidence for herein builds upon and extends the scope of this endogenous targeting concept. Importantly, SORT LNPs include classes of “out-of-the-box” supplemental molecules that can tune an LNP’s molecular composition to promote the binding of distinct protein species to the LNP, which are not typically observed in the protein corona, and enable mRNA delivery to cells and organs beyond liver hepatocytes. Because SORT LNPs include additional classes of molecules that have not been included in LNPs before, the SORT platform expands the toolbox of molecules available to control the protein corona without loss of efficacy. Although a static ex vivo incubation does not fully recapitulate the dynamic flow environment in which the protein corona is formed in vivo, studies have not identified significant differences in the relative abundance of the key proteins we discovered to associate with SORT LNPs during a static incubation versus a dynamic incubation (39–41).

It is known that the composition of the protein corona is influenced by a nanoparticle’s surface chemistry (29, 42, 43). Since SORT LNPs incorporate SORT molecules with distinct chemical structures, SORT LNPs likely have different surface chemistries underneath the PEG layer. The desorption of PEG lipid from the LNP unveils this surface, enabling specific plasma protein adsorption. It was recently shown that binding of ApoE induces rearrangement of lipids in DLin-MC3-DMA LNPs, promoting the migration of certain lipids from the core to the shell (44). These observations suggest that protein adsorption can alter the surface composition of SORT LNPs, possibly generating unique nanodomains which further promote the adsorption of distinct proteins to the LNP surface. The distinct surface chemistry of SORT LNPs can explain which specific proteins bind to the LNP. β2-GPI is known to interact with anionic phospholipids, including 18PA (45), and Vtn has been associated with DOTAP (46). Furthermore, ApoE, which facilitates liver targeting of LNPs, is highly enriched in liver SORT LNPs (28). These results further support the proteomics findings.

Understanding the molecular interactions of these individual proteins can illuminate why their enrichment might result in the observed organ-targeting properties of SORT LNPs. Interactions between ApoE and LDL-R drive hepatic accumulation of endogenous lipoproteins during cholesterol metabolism (38), possibly explaining why ApoE adsorption is a hallmark of many liver-targeting LNPs, including liver SORT. In a similar manner, Vtn could bind its cognate receptor, αvβ3 integrin, which is highly expressed by the pulmonary endothelium but not by liver cells or other vascular beds (47–49), providing a plausible explanation for why Vtn promotes lung specificity. Finally, β2-GPI can bind phosphatidyl serine, an anionic lipid exposed by senescent red blood cells to promote their filtration from the circulation in the spleen (50), suggesting how β2-GPI could be implicated in spleen SORT LNP targeting. These findings support the functional role of individual proteins on the organ-targeting properties of SORT LNPs. We acknowledge that the role of other highly enriched proteins in enhancing organ targeting, such as albumin for liver SORT (51), should not be discounted. Clusterin, highly enriched in lung SORT, could potentially play a role in evading the mononuclear phagocyte system to promote lung targeting (52, 53). Additionally, based on the key role of ApoE in driving liver targeting, the reduced binding of ApoE to spleen and lung SORT LNPs could promote extrahepatic mRNA delivery (54, 55), possibly because of the displacement of ApoE by apolipoprotein C (53), which is present in the protein coronas of spleen and lung SORT LNPs but not liver SORT (SI Appendix, Tables S4–S6).

Our proposed mechanism suggests that tuning the molecular composition of an LNP serves as a simple and effective method for manipulating the endogenous ligands which bind the nanoparticle and govern its subsequent biological fate. Our work clarifies that endogenous targeting via serum proteins acts as a targeting mechanism that can be generalized to other LNP systems besides those currently utilized for nucleic acid delivery to liver hepatocytes. With the key parameters for organ targeting identified, spleen and lung SORT LNPs may be further optimized for more efficacious tissue-specific delivery. Moving forward, the function of highly enriched serum proteins with respect to extrahepatic targeting in vivo should be further elucidated. Additionally, identifying SORT molecules that bind serum proteins distinct from those detailed within this manuscript may serve as a worthwhile strategy for the discovery of new LNPs which target other organs beyond the liver, spleen, and lungs. We view endogenous targeting, that is, engineering nanoparticle composition to facilitate interactions with distinct serum proteins and thereby tissue-specific delivery, as an effective and broad paradigm for designing nanoparticles of various material compositions to overcome liver accumulation and target extrahepatic organs.

Materials and Methods

Materials.

5A2-SC8 was synthesized and purified by following published protocols (25). DOTAP, 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphate (sodium salt) (18PA), DODAP, 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (DOPE), and 1,2-Distearoyl-rac-glycerol-methoxy(PEG MW 2000) (DSG-PEG2000) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids. Cholesterol, sucrose, SDS, and phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. DMG-PEG2000 was purchased from NOF America Corporation. The ReadyPrep 2-D Cleanup Kit, 12% Mini-PROTEAN TGX Precast Protein Gels, 2× Laemmli Buffer, and 10× Tris/Glycine/SDS were purchased from Bio-Rad. SimplyBlue Safe Stain, Pierce 660 nm Protein Assay Reagent, Ionic Detergent Compatibility Reagent for Pierce 660 nm Protein Assay Reagent, Hoechst 33342, Gibco VTN Recombinant Human Protein Truncated, and dynamic light scattering (DLS) Ultramicro cuvettes were purchased from Thermo Fisher. Innovative Research CD1 Mouse Plasma K2EDTA, Innovative Research C57BL/6 Mouse Plasma K2EDTA, Novus Biologicals Recombinant Human ApoE4 Protein, and R&D Systems Recombinant Mouse ApoH (β2-GPI) protein were purchased from Fisher Scientific. Pur-A-Lyzer Midi Dialysis Kits (MWCO, 3.5 kDa) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. CleanCap FLuc mRNA (5 moU), CleanCap Cyanine 5 FLuc mRNA (5 moU), and CleanCap EPO mRNA (5 moU) were purchased from TriLink BioTechnologies. D-Luciferin (sodium salt) was purchased from Gold Biotechnology. The hEPO enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit was purchased from Abcam. The ONE-Glo + Tox Luciferase Reporter assay kit was purchased from Promega Corporation. B6.129P2-Apoetm1Unc/J mice were acquired from the Jackson Laboratory.

Nanoparticle Preparation.

RNA-loaded LNP formulations were prepared using the ethanol dilution method. The mDLNP and the SORT formulations were developed and reported in our previous papers (11, 21, 22, 25). Unless otherwise stated, all lipids with specified molar ratios were dissolved in ethanol, and RNA was dissolved in 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 4.0). The two solutions were rapidly mixed at a ratio of 3:1 (mRNA:lipids, vol:vol) and then incubated for 10 min at room temperature. To prepare SORT LNP formulations containing anionic lipids, the anionic lipids were first dissolved in tetrahydrofuran and then mixed with other lipid components in ethanol. All formulations were named based on the additional lipids. All LNPs were prepared to have a 40:1 weight ratio of lipids to mRNA. To prepare mDLNP, a mixture of 23.8 mol % 5A2-SC8, 23.8 mol % DOPE, 47.6 mol % cholesterol, and 4.8 mol % DMG-PEG2K was dissolved in ethanol, then mixed with mRNA, and diluted in 10 mM, pH 4.0 citrate buffer at a volume ratio of 3:1 (mRNA:lipids). SORT LNPs were prepared by adding the SORT molecule to the lipid solution at a given mole %. To prepare liver SORT, a mixture of 19 mol % 5A2-SC8, 19 mol % DOPE, 38 mol % cholesterol, 4 mol % DMG-PEG2K, and 20 mol % DODAP was dissolved in ethanol, then mixed with mRNA, and diluted in 10 mM, pH 4.0 citrate buffer at a volume ratio of 3:1 (mRNA:lipids). To prepare spleen SORT, a mixture of 16.7 mol % 5A2-SC8, 16.7 mol % DOPE, 33.3 mol % cholesterol, 3.3 mol % C14-PEG2K, and 30 mol % 18PA in ethanol was prepared, then mixed with mRNA, and diluted in 10 mM, pH 3.0 citrate buffer at a volume ratio of 3:1 (mRNA:lipids). To prepare lung SORT, a mixture of 11.9 mol % 5A2-SC8, 11.9 mol % DOPE, 23.8 mol % cholesterol, 2.4 mol % C14-PEG2K, and 50 mol % DOTAP was prepared in ethanol, then mixed with mRNA, and diluted in 10 mM, pH 4.0 citrate buffer at a volume ratio of 3:1 (mRNA:lipids). After 10 min of mixing the mRNA and lipid solutions, the LNP formulations were diluted with 1× phosphate buffered saline (PBS) to 0.5 ng/µL mRNA for in vitro assays and characterization of physicochemical properties. For in vivo experiments, the formulations were dialyzed (Pur-A-Lyzer Midi Dialysis Kits, MWCO 3.5 kDa, Sigma-Aldrich) against 1× PBS for 2 h. Afterward, LNPs were diluted with PBS to a final volume of 250 µL/mouse for IV injections.

Characterization of mRNA Formulations.

Size distribution, polydispersity index, and zeta-potential were measured using DLS (Malvern MicroV model; He-Ne laser, λ = 632 nm). To measure the apparent pKa of mRNA formulations, the TNS assay was employed. mRNA formulations (60 µM total lipids) and the TNS probe (2 µM) were incubated for 5 min with a series of buffers containing 10 mM Hepes, 10 mM MES (4-morpholineethanesulfonic acid), 10 mM ammonium acetate, and 130 mM NaCl (the pH ranged from 2.5 to 11). The mean fluorescence intensity of each well (black-bottom 96-well plate) was measured by a Tecan plate reader with λEx = 321 nm and λEm = 445 nm, and data were normalized to the value of pH 2.5. Typically, the apparent pKa is defined by the pH at half-maximum fluorescence. Although this method was useful for estimating LNP global/apparent pKa for most all LNPs, it could not be used for SORT LNPs containing >40% permanently cationic lipid because these LNPs are always charged. Therefore, we instead estimated the relative pKa compared to base LNP formulation (no added SORT lipid) when 50% fluorescence normalized to the lowest fluorescence measurement was produced. This alternative calculation did not change the pKa for most LNPs but did allow the estimation of the pKa of SORT LNPs with >40% cationic lipid that agreed with experimental results for tissue-selective RNA delivery. Thus, we suggest that the standard TNS assay be used when LNPs contain a single ionizable cationic lipid and the alternative 50% normalized signal method be used for systems such as SORT that contain complex mixtures of multiple lipids harboring a variety of charge states.

In Vivo Luc mRNA Biodistribution.

All animal experiments were approved by the Institution Animal Care and Use Committees of The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center and were consistent with local, state, and federal regulations as applicable. C57BL/6 mice weighing 18 to 20 g were IV injected with various SORT LNPs containing Cy5 FLuc mRNA at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg mRNA. Ex vivo imaging (Cy5 channel) was performed 6 h postinjection. Average fluorescence of the liver, lung, and spleen were measured using Living Image Software (PerkinElmer) by drawing regions of interest around each organ. The relative fluorescence for each organ was calculated as the following:

PEG Lipid mRNA Delivery Efficacy.

C57BL/6 mice weighing 18 to 20 g were IV injected with liver, lung, and spleen SORT LNPs using either DMG-PEG2K or DSG-PEG2K as the PEG lipid component at a dose of 0.1 mg/kg (n = 3). LNPs encapsulated either FLuc mRNA or hEPO mRNA. For mice treated with FLuc mRNA, after 6 h, mice were injected with D-Luciferin (150 mg/kg, intraperitoneal [IP]) and imaged by an IVIS Lumina system (PerkinElmer). Total luminescence of target organs was quantified using Living Image Software (PerkinElmer). For mice treated with hEPO mRNA, blood was withdrawn retro-orbitally 6 h after, and serum was recovered. The serum concentration of hEPO was quantified using an ELISA kit (Abcam) to quantify mRNA delivery efficacy.

Isolation of Plasma Proteins Adsorbed to SORT LNPs.

SORT LNPs were prepared according to the previously described method and were diluted to a final lipid concentration of 1 g/L with 1× PBS. Mouse plasma was added to each LNP solution at a 1:1 volume ratio and incubated for 15 min at 37 °C. A 0.7-M sucrose solution was prepared by dissolving solid sucrose in MilliQ water. The LNP/plasma mixture was loaded onto a 0.7-M sucrose cushion of equal volume to the mixture and centrifuged at 15,300 g and 4 °C for 1 h. The supernatant was removed, and the pellet was washed with 1× PBS. Next, the pellet was centrifuged at 15,300 g and 4 °C for 5 min, and the supernatant was removed. Washing was performed twice more for a total of three washes. Following the final wash, the pellet was resuspended in 2 weight % SDS. Excess lipids were removed from each sample by following the protocol provided with the ReadyPrep 2-D Cleanup (Bio-Rad). The resulting pellet from the cleanup step was resuspended in 2× Laemmli buffer. The concentration of protein in each sample was quantified by Bradford Assay using the Pierce 660 nm Protein Assay Reagent mixed with Ionic Detergent Compatibility Reagent.

SDS–PAGE Characterization of Plasma Proteins.

Plasma proteins isolated from the surface of SORT LNPs were loaded onto a 10% Mini-PROTEAN TGX Precast Protein Gel at a volume of 10 µL and separated at 200 V. Proteins were visualized by staining the gel for 1 h with SimplyBlue Safe Stain. The gel was destained using deionized (DI) water overnight and imaged with a Licor Scanner the following day.

Preparation of Plasma Protein Samples for Mass Spectrometry.

Plasma proteins isolated from the surface of SORT LNPs were loaded onto a 12% Mini-PROTEAN TGX Precast Protein Gel at a volume of 10 µL and run into the gel 1 cm at 90 V. The gel was stained with SimplyBlue Safe Stain for 1 h to fix and visualize the proteins. After destaining for 1 h, the protein bands were excised using a sterile razor blade and sliced into 1-mm3 cubes. The cubes were added to a 1.5-mL tube that had been rinsed with 1:1 MilliQ water:Ethanol and stored at 4 °C until being submitted to the University of Texas Southwestern Proteomics Core for mass spectrometry analysis. For the CD-1 plasma samples, a Thermo Fusion Lumos mass spectrometer was used to identify the constituents of the protein corona. For the C57BL/6 samples, a Thermo QExactive HF mass spectrometer was used to identify the constituents of the protein corona. The identified proteins were ordered based on their abundance/Mw. For the proteins constituting 80% abundance of each protein corona, the proteins were grouped into functional classes based on information provided by the UniProt database. The pI of these proteins was computed using the bioinformatic resource ExPASy (35).

In Vitro Luciferase Delivery.

A-498, HuH-7, U-87 MG, or Hep G2 cells were seeded into white-bottom 96-well plates at a density of 1 × 104 cells per well and incubated at 37 °C overnight. Undifferentiated THP-1 cells were seeded into white-bottomed 96-well plates at a density of 2 × 104 cells per well and treated with 100 nM phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate overnight (to enable differentiation into macrophages). All cells were cultured in complete medium as recommended by the suppliers. Then, the old media was replaced with 100 μL media. After the formulation and dilution of SORT LNPs in 1× PBS, LNPs were incubated with 0, 0.25, 0.5, or 1.0 g protein/g total lipid of ApoE, β2-GPI, or Vtn by adding the selected protein directly to the LNP solution and incubating it with the LNPs for 15 min at 37 °C. Following incubation, each well was treated with 25 ng FLuc mRNA (n = 4). After 24 h, ONE-Glo + Tox kits were used for mRNA expression and cytotoxicity detection based on the standard protocol.

In Vitro Cellular Uptake.

A-498, HuH-7, U-87 MG, or Hep G2 cells were seeded into 12-well plates at a density of 1 × 105 cells per well and incubated at 37 °C overnight while undifferentiated THP-1 cells were seeded into 12-well plates at a density of 2 × 105 cells per well and treated with 100 nM of Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate overnight (to enable differentiation into macrophages). All cells were cultured in complete medium as recommended by the suppliers. Then, the old media was refreshed and cells treated with 250 ng Cyanine 5 FLuc mRNA encapsulated in SORT LNPs. LNPs were either uncoated, preincubated with 1.0 g protein/g total lipid ApoE, 1.0 g protein/g total lipid β2-GPI, or 0.25 g protein/g total lipid Vtn. A total of 90 min after treatment, cells were washed two times with 1× PBS and stained with Hoechst 33342 (0.1 mg ⋅ mL−1) for 10 min at 37 °C. Cells were washed twice more with PBS and then imaged by fluorescence microscopy (Keyence BZ-X800). Images were captured using a 10× magnification. All image settings were kept consistent for a single experiment. Cy5 fluorescence intensity was quantified using ImageJ software version 1.53c (NIH). Each treatment group was performed in duplicates, and five images were taken for each well.

ApoE Knockout Mouse Experiments.

SORT LNPs were prepared according to the previously described method. B6.129P2-Apoetm1Unc/J mice weighing 18 to 20 g were IV injected with mDLNP and liver, lung, and spleen SORT LNPs at a dosage of 0.1 mg/kg FLuc mRNA (n = 3). As a comparison, C57BL/6 mice weighing 18 to 20 g were IV injected with mDLNP and liver, lung, and spleen SORT LNPs at a dosage of 0.1 mg/kg FLuc mRNA (n = 3). After 6 h, mice were injected with D-Luciferin (150 mg/kg, IP) and imaged by an IVIS Lumina system (PerkinElmer). Total luminescence of target organs was quantified using Living Image Software (PerkinElmer).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

D.J.S. acknowledges grant support from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (SIEGWA18XX0), the NIH National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (R01 EB025192-01A1), the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (RP190251), and the American Cancer Society (RSG-17-012-01). We acknowledge the Southwestern Small Animal Imaging Shared Resource, which is supported in part by the Harold C. Simmons Cancer Center through a National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant (P30 CA142543). We acknowledge the University of Texas Southwestern Proteomics Core for its assistance with the mass spectrometry proteomics experiments. We especially thank Prof. Andrew Lemoff for insightful advice regarding mass spectrometry experiments. S.A.D. acknowledges financial support from the NIH Pharmacological Sciences Training Grant (GM007062) and the NIH Molecular Medicine Training Grant (GM109776). Cartoons for the figure were created using Biorender.com.

Footnotes

Competing interest statement: D.J.S., Q.C., and the Regents of the University of Texas System have filed patent applications related to this technology. D.J.S. is a cofounder of/consultant with ReCode Therapeutics, which has licensed intellectual property from the University of Texas Southwestern.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2109256118/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.

References

- 1.Whitehead K. A., Langer R., Anderson D. G., Knocking down barriers: Advances in siRNA delivery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 8, 129–138 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller J. B., Siegwart D. J., Design of synthetic materials for intracellular delivery of RNAs: From siRNA-mediated gene silencing to CRISPR/Cas gene editing. Nano Res. 11, 5310–5337 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sahin U., Karikó K., Türeci Ö., mRNA-based therapeutics—Developing a new class of drugs. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 13, 759–780 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hajj K. A., Whitehead K. A., Tools for translation: Non-viral materials for therapeutic mRNA delivery. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2, 17056 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kowalski P. S., Rudra A., Miao L., Anderson D. G., Delivering the messenger: Advances in technologies for therapeutic mRNA delivery. Mol. Ther. 27, 710–728 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doudna J. A., Charpentier E., Genome editing. The new frontier of genome engineering with CRISPR-Cas9. Science 346, 1258096 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sander J. D., Joung J. K., CRISPR-Cas systems for editing, regulating and targeting genomes. Nat. Biotechnol. 32, 347–355 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang H. X., et al. , CRISPR/Cas9-based genome editing for disease modeling and therapy: Challenges and opportunities for nonviral delivery. Chem. Rev. 117, 9874–9906 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ventura A., Jacks T., MicroRNAs and cancer: Short RNAs go a long way. Cell 136, 586–591 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kong N., et al. , Synthetic mRNA nanoparticle-mediated restoration of p53 tumor suppressor sensitizes p53-deficient cancers to mTOR inhibition. Sci. Transl. Med. 11, eaaw1565 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng Q., et al. , Dendrimer-based lipid nanoparticles deliver therapeutic FAH mRNA to normalize liver function and extend survival in a mouse model of hepatorenal tyrosinemia type I. Adv. Mater. 30, e1805308 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akinc A., et al. , The Onpattro story and the clinical translation of nanomedicines containing nucleic acid-based drugs. Nat. Nanotechnol. 14, 1084–1087 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pardi N., Hogan M. J., Porter F. W., Weissman D., mRNA vaccines—A new era in vaccinology. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 17, 261–279 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feldman R. A., et al. , mRNA vaccines against H10N8 and H7N9 influenza viruses of pandemic potential are immunogenic and well tolerated in healthy adults in phase 1 randomized clinical trials. Vaccine 37, 3326–3334 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kose N., et al. , A lipid-encapsulated mRNA encoding a potently neutralizing human monoclonal antibody protects against chikungunya infection. Sci. Immunol. 4, eaaw6647 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wei T., et al. , Delivery of tissue-targeted scalpels: Opportunities and challenges for in vivo CRISPR/Cas-based genome editing. ACS Nano 14, 9243–9262 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adams D., et al. , Patisiran, an RNAi therapeutic, for hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 379, 11–21 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baden L. R., et al. , COVE Study Group, Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 403–416 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Polack F. P., et al. , C4591001 Clinical Trial Group, Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 383, 2603–2615 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kulkarni J. A., Cullis P. R., van der Meel R., Lipid nanoparticles enabling gene therapies: From concepts to clinical utility. Nucleic Acid Ther. 28, 146–157 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheng Q., et al. , Selective organ targeting (SORT) nanoparticles for tissue-specific mRNA delivery and CRISPR-Cas gene editing. Nat. Nanotechnol. 15, 313–320 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wei T., Cheng Q., Min Y. L., Olson E. N., Siegwart D. J., Systemic nanoparticle delivery of CRISPR-Cas9 ribonucleoproteins for effective tissue specific genome editing. Nat. Commun. 11, 3232 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee S. M., et al. , A systematic study of unsaturation in lipid nanoparticles leads to improved mRNA transfection in vivo. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 60, 5848–5853 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu S., et al. , Membrane-destabilizing ionizable phospholipids for organ-selective mRNA delivery and CRISPR-Cas gene editing. Nat. Mater. 20, 701–710 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou K., et al. , Modular degradable dendrimers enable small RNAs to extend survival in an aggressive liver cancer model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 520–525 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheng X., Lee R. J., The role of helper lipids in lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) designed for oligonucleotide delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 99, 129–137 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang Y.-N., Poon W., Tavares A. J., McGilvray I. D., Chan W. C. W., Nanoparticle-liver interactions: Cellular uptake and hepatobiliary elimination. J. Control. Release 240, 332–348 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akinc A., et al. , Targeted delivery of RNAi therapeutics with endogenous and exogenous ligand-based mechanisms. Mol. Ther. 18, 1357–1364 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Monopoli M. P., Aberg C., Salvati A., Dawson K. A., Biomolecular coronas provide the biological identity of nanosized materials. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 779–786 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jayaraman M., et al. , Maximizing the potency of siRNA lipid nanoparticles for hepatic gene silencing in vivo. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 51, 8529–8533 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mui B. L., et al. , Influence of polyethylene glycol lipid desorption rates on pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of siRNA lipid nanoparticles. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2, e139 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilson S. C., et al. , Real time measurement of PEG shedding from lipid nanoparticles in serum via NMR spectroscopy. Mol. Pharm. 12, 386–392 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Docter D., et al. , Quantitative profiling of the protein coronas that form around nanoparticles. Nat. Protoc. 9, 2030–2044 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ban Z., et al. , Machine learning predicts the functional composition of the protein corona and the cellular recognition of nanoparticles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117, 10492–10499 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Artimo P., et al. , ExPASy: SIB bioinformatics resource portal. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, W597–W603 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lara S., et al. , Identification of receptor binding to the biomolecular corona of nanoparticles. ACS Nano 11, 1884–1893 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thiagarajan P., Le A., Benedict C. R., β(2)-glycoprotein I promotes the binding of anionic phospholipid vesicles by macrophages. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 19, 2807–2811 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mahley R. W., Apolipoprotein E: Cholesterol transport protein with expanding role in cell biology. Science 240, 622–630 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Amici A., et al. , In vivo protein corona patterns of lipid nanoparticles. RSC Adv. 7, 1137–1145 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pozzi D., et al. , The biomolecular corona of nanoparticles in circulating biological media. Nanoscale 7, 13958–13966 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Palchetti S., et al. , The protein corona of circulating PEGylated liposomes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1858, 189–196 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Walkey C. D., Chan W. C., Understanding and controlling the interaction of nanomaterials with proteins in a physiological environment. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 2780–2799 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang Y., Wu J. L. Y., Lazarovits J., Chan W. C. W., An analysis of the binding function and structural organization of the protein corona. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 8827–8836 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sebastiani F., et al. , Apolipoprotein E binding drives structural and compositional rearrangement of mRNA-containing lipid nanoparticles. ACS Nano 15, 6709–6722 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hammel M., et al. , Mechanism of the interaction of β(2)-glycoprotein I with negatively charged phospholipid membranes. Biochemistry 40, 14173–14181 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Caracciolo G., Pozzi D., Capriotti A. L., Cavaliere C., Laganà A., Effect of DOPE and cholesterol on the protein adsorption onto lipid nanoparticles. J. Nanopart. Res. 15, 1498 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Singh B., Fu C., Bhattacharya J., Vascular expression of the alpha(v)beta(3)-integrin in lung and other organs. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 278, L217–L226 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Couvelard A., et al. , Expression of integrins during liver organogenesis in humans. Hepatology 27, 839–847 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Simpson A., Horton M. A., Expression of the vitronectin receptor during embryonic development: An immunohistological study of the ontogeny of the osteoclast in the rabbit. Br. J. Exp. Pathol. 70, 257–265 (1989). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dinkla S., et al. , Phosphatidylserine exposure on stored red blood cells as a parameter for donor-dependent variation in product quality. Blood Transfus. 12, 204–209 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Miao L., et al. , Synergistic lipid compositions for albumin receptor mediated delivery of mRNA to the liver. Nat. Commun. 11, 2424 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schöttler S., et al. , Protein adsorption is required for stealth effect of poly(ethylene glycol)- and poly(phosphoester)-coated nanocarriers. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 372–377 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kowal R. C., et al. , Opposing effects of apolipoproteins E and C on lipoprotein binding to low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein. J. Biol. Chem. 265, 10771–10779 (1990). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang R., et al. , Helper lipid structure influences protein adsorption and delivery of lipid nanoparticles to spleen and liver. Biomater. Sci. 9, 1449–1463 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Parhiz H., et al. , PECAM-1 directed re-targeting of exogenous mRNA providing two orders of magnitude enhancement of vascular delivery and expression in lungs independent of apolipoprotein E-mediated uptake. J. Control. Release 291, 106–115 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.