Abstract

Introduction

The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to investigate the efficacy and safety of emergent transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) in patients with decompensated aortic stenosis (AS) by comparing the clinical outcomes with the patients who had received the elective TAVI.

Methods

By searching PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane databases, we obtained the studies comparing the clinical outcomes of emergent TAVI and elective TAVI. Finally, 14 studies were included.

Results

A total of 14 eligible articles with 73,484 patients were included in this meta-analysis. Emergent TAVI was associated with a higher mortality during hospitalization (HR 2.09, 95% CI [1.39 to 3.14]), 30 days (HR 2.29, 95% CI [1.69 to 3.10]), and 1 year (HR 1.96, 95% CI [1.55 to 2.49]). Consistently, the incidence of acute kidney injury (AKI) (RR 2.48, 95% CI [1.85 to 3.32]), dialysis (RR 2.37, 95% CI [1.95 to 2.88]), bleeding (RR 1.62, 95% CI [1.27 to 2.08]), major bleeding (RR 1.05, 95% CI [1.00 to 1.10]), and 30-day rehospitalization (RR 1.30, 95% CI [1.07, 1.58]) were more common in patients receiving emergent TAVI. No statistical differences were found in the occurrence rate of vascular complications (RR 1.11, 95% CI [0.90, 1.36]), major vascular complications (RR 1.14, 95% CI [0.52, 2.52]), permanent pacemaker (PPM) placement (RR 1.05, 95% CI [0.99, 1.11]), cerebrovascular events (RR 1.11, 95% CI [0.98, 1.25]), moderate to severe paravalvular leakage (PVL) (RR 1.23, 95% [CI 0.94 to 1.61]), and device success (RR 0.99, 95% CI [0.97, 1.01]).

Conclusion

Emergent TAVI is associated with some postoperative complications and increased mortality compared with elective TAVI. Emergent TAVI should be implemented cautiously and individually.

1. Introduction

Aortic stenosis (AS) is one of the commonest valvular heart diseases, and its prevalence increased markedly with population aging [1, 2]. A conservative, multicenter registry reported that the 1-year mortality in the patient with severe AS and heart failure that treated conservatively could go as high as 40%, which was about 3 times that of patients without heart failure [3]. However, there were no guidelines to explicitly recommend the treatment of acute decompensated AS. TAVI provided a less invasive option for AS, which had comparable and sometimes superior results to surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR), while there were no recommendations for TAVI to treat acute decompensated AS. Recently, several studies reported the application of emergent TAVI in acute decompensated AS. Therefore, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to panoramically and quantitatively investigate the efficacy and safety of emergent TAVI by comparing the outcomes with elective TAVI in order to comprehensively illustrate the clinical outcomes of emergent TAVI.

2. Methods

The present systematic review and meta-analysis was performed in conformity to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement.

2.1. Registration

Our systematic review was registered online in INPLASY (registration number: 202140050, https://inplasy.com/inplasy-2021-4-0050/).

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

The inclusion criteria in this meta-analysis were ① reporting outcome indicators for both emergent TAVI and elective TAVI; ② randomized clinical trials and prospective/retrospective cohort studies; and ③ presenting the specific number or incidence of outcome indicators or displayed the survival curve. The exclusion criteria included ① non-English literature; ② repetitive published literature; ③ research that cannot extract or transform key data; and ④ certain publication type (e.g., case reports, reviews, meta-analysis, editorials, guidelines, and letters).

Our primary outcomes were mortality within hospitalization, 30 days, and 1 year after TAVI. The secondary outcomes included device success; rehospitalization within 30 days after TAVI; and procedural-related complications including acute kidney injury (AKI), the need for dialysis, bleeding, moderate to severe paravalvular leakage (PVL), vascular complications, permanent pacemaker (PPM) implantation, and cerebrovascular events including TIA and stroke, as defined in the original studies. When information about the outcome of interest is unavailable, this study was not analyzed for this endpoint.

2.3. Data Sources and Study Selection

A literature search of Embase, PubMed, and Cochrane Library was performed using following search strategies: ((emergent OR emergency OR urgent OR emergently OR urgently) AND (elective OR electively OR nonurgent) AND (Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation OR Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement Implantation OR TAVI OR TAVR)) OR eTAVI OR eTAVR. We also reviewed corresponding references of retrieved studies to identify relevant clinical trials that were neglected. The time interval of the search was from Jan. 2009 to Apr. 2021. The PRISMA diagram displays the process for the filtration and selecting of references.

2.4. Data Extraction and Quality Evaluation

Two researchers (SRC and LJL) independently screened literatures and extracted data. If under the circumstance of disagreement, it shall be settled through discussion or negotiation with a third party. After excluding the obviously unrelated articles, further read abstract and the full text to determine if they meet the inclusion criteria. If there were lack of information, researchers tried to contact the author as far as possible to acquire the relevant data. Data extraction included but was not limited to ① basic information of included studies: research topic, first author, published journal, etc.; ② baseline characteristic and intervention measure of research objects; ③ key element of bias risk assessment; and ④ outcome indicators concerned. If mortality or the number of deaths were not presented directly, the digitizing software Engauge Digitizer 4.1 was used to gain information from survival cure. The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) was used to estimate the quality of included observational studies.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Stata 15.1 software was used for statistical analysis. The risk ratio (RR) or hazard ratio (HR) was used as the statistic of effect analysis. The random effect model was used for meta-analysis. Heterogeneity was evaluated by calculating I2 statistic as well as its P value. Heterogeneity was appraised by the Galbraith radial plot, cumulative analysis, and sensitivity analysis. Meta-regression was also used to analyze the contribution of the remaining characteristics of each study to heterogeneity. A two-sided P value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

2.6. Publication Bias Analysis

The funnel plot was drawn and intuitively judged for the main outcome measures. If the distribution was a left-right symmetrical inverted funnel, it indicates that there was no remarkable publication bias in the study. Begg's rank correction test and Egger's linear regression were performed, and P < 0.05 indicates that there might be publication bias.

3. Results

3.1. Literature Search and Eligible Studies

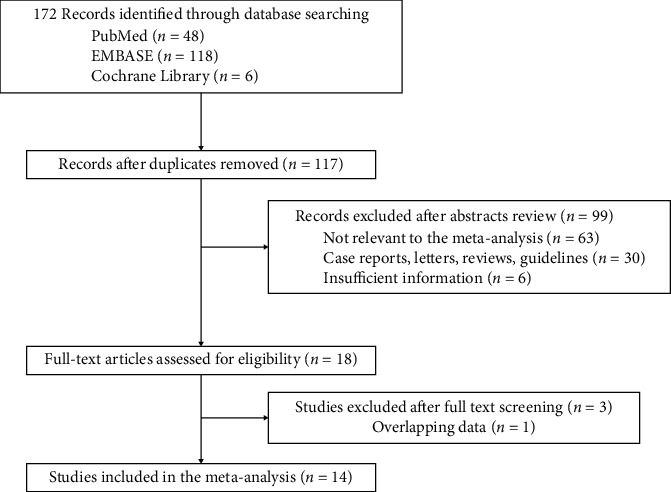

The selection process details are illustrated in Figure 1. We initially retrieved a total of 172 citations from Cochrane Library, Embase, and PubMed, 55 of which were duplicated and removed and a total of 99 publications were excluded behind screening abstracts and titles. After reading the full text and excluding overlapping data, 14 retrospective cohort studies were finally included in our meta-analysis. The characteristics of the 14 studies and NOS assessments are summarized in Table 1. A range of 5–9 stars was gained, which indicates median to high methodological quality of the included studies. The baseline of the included overall studies is shown in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the identification process for eligible studies.

Table 1.

Characteristics and methodological quality assessments.

| Newcastle–Ottawa scale | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Year | Location | Study design | Study period | Outcomes | Selection | Comparability | Outcome |

| Alnasser, S. et al | 2014 | Canada | Prospective cohort study | 2009–2014 | ②④⑤⑦⑨⑩⑪⑭ | ★★★★ | ★☆ | ★★★ |

| Landes, U. et al | 2016 | Israel | Prospective cohort study | 2008.11–2015.4 | ①④⑥⑦⑧⑨⑩⑪⑫⑬⑭ | ★★★★ | ★☆ | ★★★ |

| Frerker, C. et al | 2016 | Germany | Cohort study | 2008.8–2013.9 | ①③④⑥⑧⑨⑩⑪⑫⑭ | ★★★★ | ★☆ | ★★☆ |

| Angeras, O. et al | 2017 | Sweden | Cohort study | 2008.5–2016.12 | ①③ | ★★☆★ | ☆☆ | ★★☆ |

| Kolte, D. et al | 2018 | USA | Retrospective cohort study | 2011.11–2016.6 | ①②③④⑤⑥⑧⑩⑪⑫⑭ | ★★★★ | ★★ | ★★☆ |

| Pino, J.E. et al | 2018 | USA | Retrospective cohort study | — | ①③ | ★★★★ | ☆☆ | ★★☆ |

| Ichibori, Y. et al | 2019 | USA | Retrospective cohort study | 2014.4–2017.3 | ①②③④⑥⑧⑨⑩⑪⑬⑭ | ★★★★ | ★☆ | ★★☆ |

| Elbaz-Greener, G. et al | 2019 | Canada | Retrospective cohort study | 2010.4–2016.3 | ①④⑤⑥⑦⑩⑪⑬ | ★★★★ | ★☆ | ★★★ |

| Elbadawi, A. et al | 2020 | USA | Retrospective cohort study | 2011–2014 | ②④⑤⑥⑨⑩⑪ | ★★★★ | ★★ | ★☆★ |

| Chen, K. et al | 2020 | USA | Retrospective cohort study | 2012.4–2017.7 | ①③⑤⑨⑩⑪⑬ | ★★★★ | ★☆ | ★★☆ |

| Bianco, V. et al | 2020 | USA | Retrospective cohort study | 2011–2018 | ①③⑤⑩⑪⑬⑭ | ★★★★ | ★★ | ★★★ |

| Enta, Y. et al | 2020 | Japan | Retrospective cohort study | 2013.10–2016.7 | ①②③④⑤⑥⑧⑩⑪⑫⑭ | ★★★★ | ★☆ | ★★★ |

| Berkovitch, A. et al | 2020 | Israel | Prospectively cohort study | — | ②③ | ★★☆★ | ★☆ | ★★☆ |

| Kabahizi, A. et al | 2021 | UK | Retrospective cohort study | 2007–2019 | ①②③④⑥⑧⑩⑫⑭ | ★★★★ | ★☆ | ★★★ |

Outcomes: ① 30-day mortality; ② in-hospital mortality; ③ one-year mortality; ④ AKI; ⑤ new dialysis; ⑥ major bleeding; ⑦ major and minor bleeding; ⑧ major vascular complication; ⑨ major and minor vascular complications; ⑩ PPM placement; ⑪ cerebrovascular events; ⑫ device success; ⑬ rehospitalization; ⑭ moderate to severe PVL.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of patients in the emergent TAVI group and elective TAVI group.

| Study | Sample size | Age, y | Female sex | STS score | Diabetes mellitus | Hypertension | Smoke | COPD | Chronic kidney injury | Dialysis-dependent | Previous stroke or TIA | Previous myocardial infarction | Previous CABG | Atrial fibrillation | Previous PCI | Peripheral vascular disease | NYHA functional class III/IV | Aortic valve area | Mean transvalvular aortic pressure gradient | LVEF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Landes, U. et al | Elective TAVI 342 | 82.1 ± 6.2 | 192 | 7.3 ± 4.5 | 111 | 314 | — | 73 | 103 | — | 61 | 29 | 68 | 106 | — | 54 | 325 | 0.63 ± 0.18 | 51 ± 18 | — |

| Emergent TAVI 27 | 80.1 ± 9.7 | 15 | 9.7 ± 6.1 | 13 | 25 | — | 5 | 15 | — | 8 | 4 | 6 | 12 | — | 6 | 27 | 0.59 ± 0.19 | 52 ± 8.8 | — | |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Kolte, D. et al | Elective TAVI 36,090 | 83.3 ± 7.4 | 17474 | 6.45 ± 3.7 | 12690 | 32477 | 1672 | — | — | 1195 | 7520 | 8253 | 10212 | 14664 | 12531 | 10948 | 28641 | — | — | 57.7 ± 11.1 |

| Emergent TAVI 3952 | 83.3 ± 7.4 | 1902 | 12.5 ± 7.6 | 1557 | 3608 | 231 | — | — | 300 | 887 | 1323 | 1000 | 2002 | 1395 | 1302 | 3656 | — | — | 49.8 ± 17.1 | |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Ichibori, Y. et al | Elective TAVI 369 | 81.6 ± 8.5 | 188 | 6.4 ± 3.6 | 160 | — | 17 | 97 | — | 12 | 55 | 85 | 100 | 135 | 148 | 74 | 268 | 0.74 ± 0.18 | 40.8 ± 15.5 | 53.6 ± 12.9 |

| Emergent TAVI 78 | 80.8 ± 9.6 | 38 | 7.4 ± 4.3 | 35 | — | 6 | 16 | — | 8 | 16 | 19 | 14 | 36 | 27 | 15 | 60 | 0.65 ± 0.17 | 42.5 ± 16.9 | 48.2 ± 15.5 | |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Frerker, C. et al | Elective TAVI 744 | 80 ± 7 | 395 | — | 219 | 620 | — | 120 | 283 | — | 101 | — | — | 320 | — | 166 | — | 0.8 ± 0.3 | 38.4 ± 15.6 | 52.4 ± 13.2 |

| Emergent TAVI 27 | 78 ± 9 | 15 | — | 11 | 22 | — | 6 | 17 | — | 4 | — | — | 14 | — | 9 | — | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 35.1 ± 16.8 | 39.5 ± 15.4 | |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Elbadawi, A. et al | Elective TAVI 10,121 | 80.6 ± 8.85 | 4768 | — | 3699 | 7978 | 2987 | — | 3792 | — | — | 1354 | 2237 | — | 2027 | 2968 | — | — | — | — |

| Emergent TAVI 10089 | 81.0 ± 9.05 | 5072 | — | 3470 | 7826 | 2413 | — | 4207 | — | — | 1230 | 1897 | — | 1713 | 2953 | — | — | — | — | |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Alnasser, S. et al | Elective TAVI 152 | 83 ± 7 | — | 8.6 ± 4.7 | 42 | 132 | — | — | — | 5 | — | 37 | 48 | 25 | — | 19 | 139 | 0.59 ± 0.18 | 51.8 ± 15.6 | 55.0 ± 10.7 |

| Emergent TAVI 52 | 85.75 ± 5.19 | — | 7.1 ± 4.9 | 15 | 42 | — | — | — | 3 | — | 21 | 15 | 9 | — | 9 | 52 | 0.65 ± 0.16 | 49.0 ± 16.7 | 49.9 ± 13.8 | |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Elbaz-Greener, G. et al | Elective TAVI 1741 | 81.9 ± 7.2 | 804 | — | 780 | 1644 | — | 618 | 168 | 51 | — | — | 424 | 442 | 617 | 94 | — | — | — | — |

| Emergent TAVI 429 | 81.3 ± 8.9 | 192 | — | 211 | 395 | — | 159 | 75 | 22 | — | — | 97 | 137 | 121 | 25 | — | — | — | — | |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Chen, K. et al | Elective TAVI 463 | 85.3 ± 5.9 | 192 | 5.4 ± 2.8 | 158 | 414 | 14 | 174 | — | — | 46 | 136 | 109 | 218 | — | 120 | 376 | 0.64 ± 0.22 | 44.4 ± 11.2 | 55.6 ± 14.9 |

| Emergent TAVI 139 | 84.9 ± 6.7 | 59 | 7 ± 3.2 | 54 | 128 | 5 | 50 | — | — | 17 | 43 | 37 | 66 | — | 28 | 120 | 0.64 ± 0.22 | 46.4 ± 12.7 | 50 ± 15 | |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Bianco, V. et al | Elective TAVI 946 | 82.6 ± 6.7 | 484 | — | 387 | 844 | 54 | 77 | — | 32 | 222 | 348 | 245 | 388 | 327 | 345 | 680 | — | 48.5 ± 13.4 | — |

| Emergent TAVI 247 | 81.3 ± 8.9 | 116 | — | 109 | 220 | 28 | 35 | — | 22 | 56 | 118 | 72 | 120 | 91 | 83 | 231 | — | 49.3 ± 18.3 | — | |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Enta, Y. et al | Elective TAVI 1526 | 84.3 ± 5.0 | 1075 | 6.8 ± 3.4 | 401 | 1203 | 37 | 282 | — | — | 211 | 103 | 111 | 308 | 404 | 219 | 740 | 0.64 ± 0.17 | 50.5 ± 18.0 | 58.5 ± 11.9 |

| Emergent TAVI 87 | 84.9 ± 7.0 | 61 | 14.3 ± 9.6 | 29 | 65 | 7 | 15 | — | — | 20 | 13 | 9 | 31 | 27 | 27 | 77 | 0.56 ± 0.15 | 50.2 ± 20.0 | 47.9 ± 16.1 | |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Kabahizi, A. et al | Elective TAVI 975 | 82.0 ± 2.1 | 455 | 4.56 ± 2.69 | 176 | — | — | 198 | 121 | 16 | — | — | 140 | 187 | — | 229 | — | — | — | — |

| Emergent TAVI 182 | 80.1 ± 7.0 | 77 | 5.79 ± 4.13 | 40 | — | — | 34 | 34 | 3 | — | — | 22 | 42 | — | 42 | — | — | — | — | |

STS: Society of Thoracic Surgeons Cardiac Surgery Risk Models, COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention, NYHA: New York Heart Association, LVEF: left ventricular ejection fractions, CABG: coronary artery bypass graft, TIA: transient ischemia attack. Continuous variables were expressed as means ± SD.

3.2. Outcomes

3.2.1. Mortality

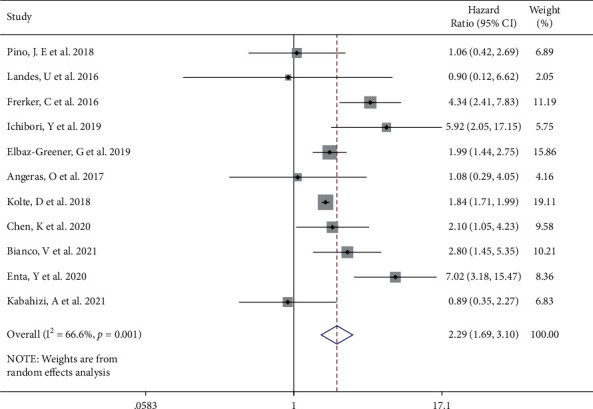

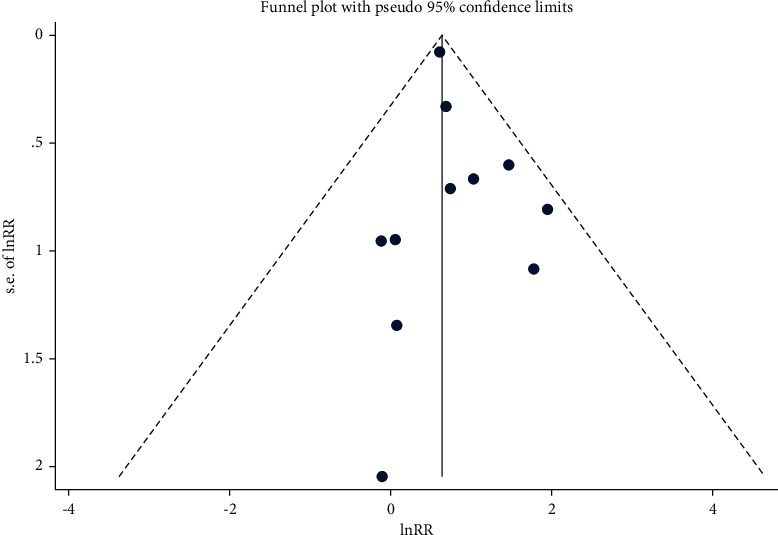

A total of 11 [4–14] studies reported all-cause 30-day mortality after TAVI in the emergent TAVI group and the elective TAVI group. The heterogeneity test (I2 = 66.6%, Q test P=0.001, Figure 2) indicated the significant heterogeneity between the selected literatures. The random effect model was used for combining the results. Emergent TAVI had significant higher 30-day mortality than elective TAVI (HR 2.29, 95% CI [1.69 to 3.10], Figure 2). The Galbraith radial plot (Supplemental Figure S1(a)) and cumulative meta-analysis (Supplemental Figure S1(b)) did not find a clear source of heterogeneity. Through sensitivity analysis of 11 literatures, we found that the research of Kolte et al. [10] might have an impact on heterogeneity (Supplemental Figure S1(c)). After deleting this study, the other 10 literatures showed the same trend as before, but there was still strong heterogeneity (Supplemental Figure S1(d)). Univariate meta-expression showed the sample size, gender, age, and basic health status of patients could not explain the source of heterogeneity (Supplemental Table 1). Besides, no evidence of publication bias was found according to funnel plots (Begg's test P=0.876 and Egger's test P=0.339, Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Forest plot showing the 30-day mortality of the emergent TAVI increased. CI, confidence interval.

Figure 3.

Funnel plot analysis of publication bias.

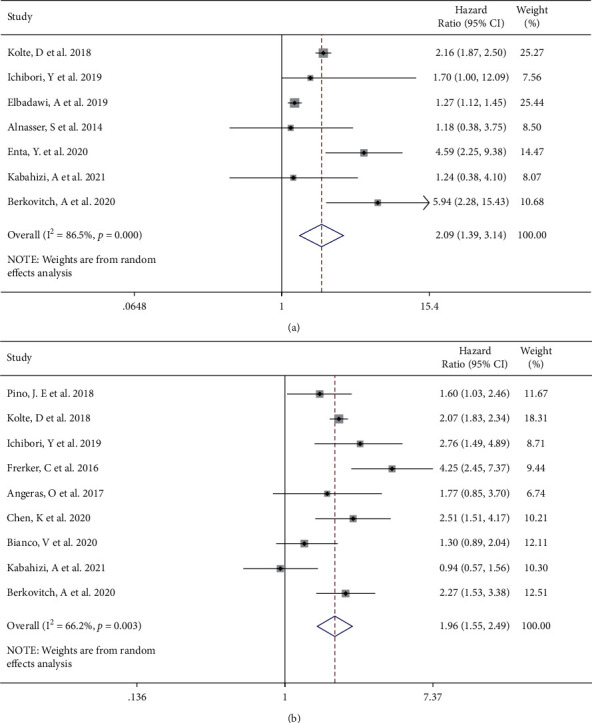

With regard to mortality during hospitalization and one year after TAVI, there were 7 [8, 10, 13–17] and 9 [4, 8, 10, 11, 13, 17] studies describing the pertinent data, respectively. A significant difference was noted between emergent and elective TAVI on the mortality at hospitalization (emergent vs selective, HR 2.09, 95% CI [1.39 to 3.14], I2 = 86.5%, Q test P < 0.001, Figure 4(a)) and 1 year (HR 1.96, 95% CI [1.55 to 2.49], I2 = 66.2%, Q test P=0.003, Figure 4(b)) in the random effect model. Cumulative meta-analysis and sensitivity analysis suggested the research of Elbadawi et al. [15] contributed to heterogeneity in the mortality at hospitalization (Supplemental Figures S2(a) and S2(b)). After excluding the study, emergent TAVI was still considered to have higher in-hospital mortality (emergent vs selective, HR 2.48, 95% CI [1.58 to 3.91], I2 = 52.2%, Q test P=0.063, Supplemental Figure S2(c)). Meta-regression did not find factors that might influence the results, in the case of sufficient original data support (Supplemental Table. 2). No exact source of heterogeneity was found in the Galbraith radial plot, cumulative meta-analysis, sensitivity analysis, and meta-regression of mortality at 1 year (Supplemental Figures S2(d)–S2(f), Supplemental Table 3). Begg's test and Egger's test for hospitalization mortality (Begg's test P=0.707, Egger's test P=0.483) and 1 year mortality (Begg's test P=0.602, Egger's test P=0.827) indicating no publication bias exist.

Figure 4.

Forest plot showing a higher incidence of in-hospital (a) and 1-year (b) mortality of the emergent TAVI group. CI, confidence interval.

3.2.2. Procedural Complications

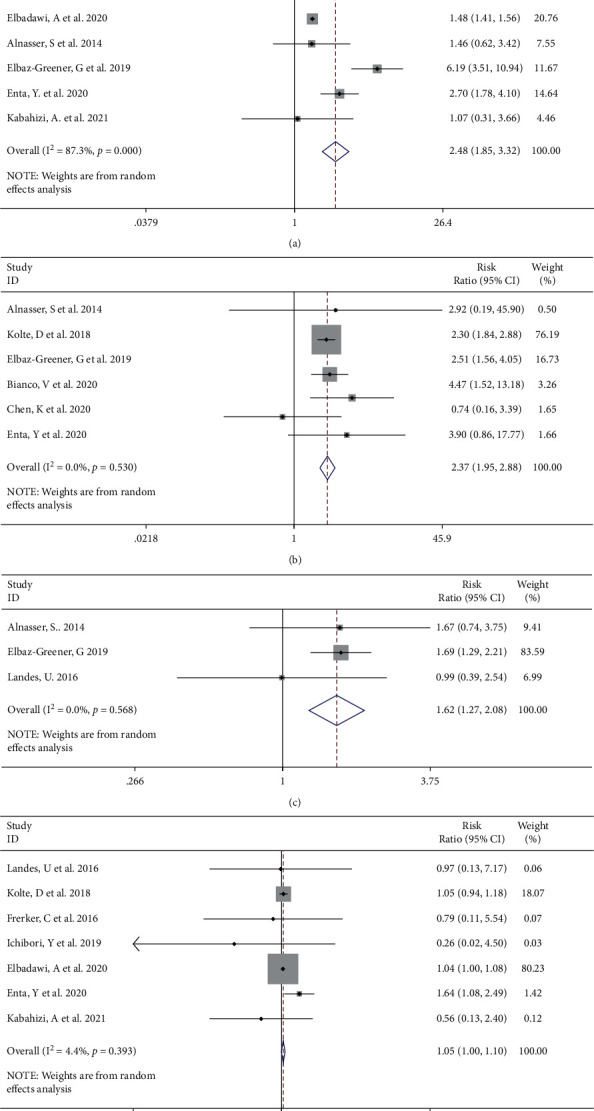

A variety of postoperative complications have been described in multiple studies. A total of 9 [4, 8, 10, 12–16] and 7 [6, 7, 9, 10, 14–16] studies investigated AKI and the need for dialysis after emergent TAVI. A random effect meta-analysis confirmed a statistically significant difference in opposition to the emergent TAVI from the aspects of AKI (RR 2.48, 95% CI [1.85 to 3.32], I2 = 87.3%, Q test P < 0.001, Figure 5(a)). After sensitivity analysis, we found that the study of Elbadawi et al. [15] had an impact on heterogeneity (Supplemental Figure S3(a)). After removing this study, the trend of effect quantity combined by meta-analysis did not change (Supplemental Figure S3(b)). In the aspect of dialysis, through sensitivity analysis, we found that the study of Elbadawi et al. [15] was a source of heterogeneity (Supplemental Figure S3(c)), so the observation was deleted. There was no statistical heterogeneity in the remaining studies (I2 = 0%, P=0.530); meta-analysis showed that emergent TAVI was inferior in the occurrence of dialysis (emergent vs selective, HR 2.37, 95% CI [1.95 to 2.88], Figure 5(b)). The prevalence rates of bleeding [9, 12, 16] (RR 1.62, 95% CI [1.27 to 2.08], I2 = 0.0%, Q test P=0.568, Figure 5(c)) and major bleeding [4, 8, 10, 12–15] (RR 1.05, 95% CI [1.00 to 1.10], I2 = 4.4%, Q test P=0.393, Figure 5(d)) were aggravated to a certain extent in the emergent TAVI group. Egger's test displayed evidence of the publication bias for AKI (P=0.034). The trim-and-fill analysis simulated and added 3 missing studies (RR 1.663, 95% CI [1.222, 2.261]). Begg's test and Egger's test found no evidence of publication bias for dialysis (Begg's test P=0.548, Egger's test P=0.397) and major bleeding (Begg's test P=0.548, Egger's test P=0.986).

Figure 5.

Forest plot showing the incidence of AKI (a), dialysis (b), bleeding (c), and major bleeding (d) increased in the emergent TAVI group. CI, confidence interval.

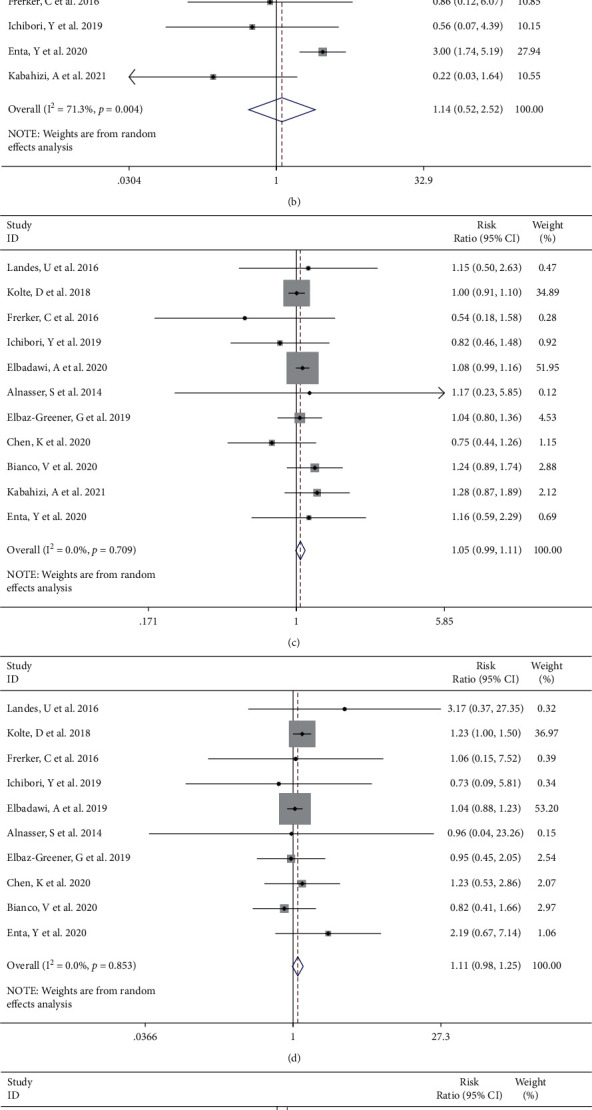

Compared with those patients underwent elective TAVI, the emergent TAVI group showed no significant statistical difference in the incidence of vascular complications [4, 6, 8, 12, 15, 16] from random effects (RR 1.11, 95% CI [0.90 to 1.36], I2 = 15.1%, Q test P=0.317, Figure 6(a)). There was no significant difference from random effects in major vascular complications between two groups (RR 1.14, 95% CI [0.52 to 2.52], I2 = 71.3%, Q test P=0.004, Figure 6(b)). After removing one study with high heterogeneity through sensitivity analysis, the trend of the results did not change, and there was no decrease in heterogeneity (Supplemental Figures S3(d) and S3(e)). Consistently, there was no significant difference in the rates of PPM placement [4, 6, 10, 12–16] (RR 1.05, 95% CI [0.99 to 1.11], I2 = 0.0%, Q test P=0.709, Figure 6(c)) and cerebrovascular events [4, 6, 10, 12, 14–16] (RR 1.11, 95% CI [0.98 to 1.25], I2 = 0.0%, Q test P=0.853, Figure 6(d)). Moderate to severe PVL was described in 8 [4, 7, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16] studies. There was no statistically significant difference in opposition to the emergent TAVI group (RR 1.23, 95% CI [0.94 to 1.61], I2 = 18.1%, Q test P=0.287, Figure 6(e)). Egger's test and Begg's test suggested no evidence of publication bias for vascular complications (Egger's test P=0.089, Begg's test P=1.000), major vascular complications (Begg's test P=1.000, Egger's test P=0.558), PPM placement (Begg's test P=0.533, Egger's test P=0.666), cerebrovascular events (Begg's test P=0.592, Egger's test P=0.683), and moderate to severe PVL (Begg's test P=0.532, Egger's test P=0.907).

Figure 6.

Forest plot showing there was no significant difference in vascular complications (a), major vascular complications (b), PPM placement (c), cerebrovascular events (d), and moderate to severe PVL (e) between the emergent TAVI group and elective TAVI group. CI, confidence interval.

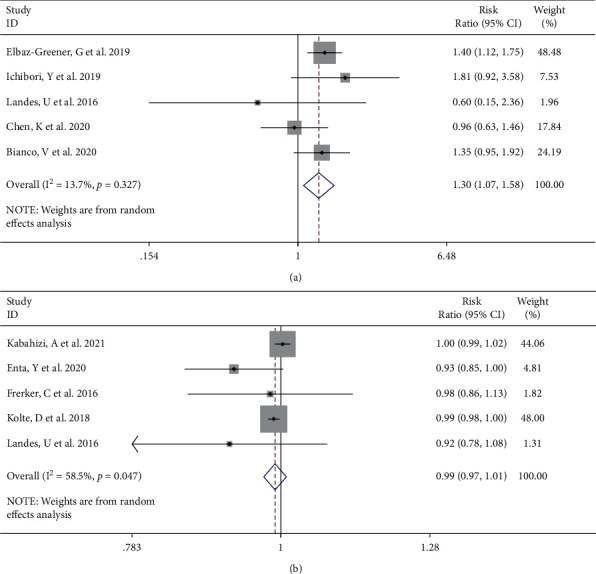

The need for rehospitalization was described in 5 [6, 9, 12] studies. We found that emergent TAVI was associated with negative prognosis in terms of rehospitalization rate (RR 1.30, 95% CI [1.07 to 1.58], I2 = 13.7%, Q test P=0.327, Figure 7(a)). There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups in comparison of device success [4, 10, 12–14] (RR 0.99, 95% CI [0.97 to 1.01], I2 = 58.5%, Q test P=0.047, Figure 7(b)). Sensitivity analysis did not show a contribution to heterogeneity reduction (Supplemental Figures S3(f) and S3(g)).

Figure 7.

Forest plot showing rehospitalization rate (a) and device success (b) between the emergent TAVI group and elective TAVI group. CI, confidence interval.

4. Discussion

Main results of our systematic review and meta-analysis were as follows: (1) emergent TAVI was associated with higher incidence of 30-day, in-hospital, and 1-year mortality; and (2) in terms of postoperative adverse events, emergent TAVI had higher rates of AKI, dialysis, bleeding, and major bleeding. On the contrary, vascular complications, major vascular complications, PPM, cerebrovascular events, and moderate to severe PVL were comparable between emergent TAVI and elective TAVI.

Management of patients with acute decompensated AS remains challenging. Patients with acute decompensated aortic stenosis were usually not recommended for SAVR because of the high risk [10]. Standard medical therapy and balloon aortic valvuloplasty (BAV) alone was associated with various harmful outcomes after one year [18]. In this context, emergent TAVI and emergent BAV as the “bridge” for TAVI/SAVR have become the few optional strategies [19]. More and more studies have been proposed to investigate the safety and efficacy of emergent TAVI by comparing with elective TAVI conducted at the same time. The mortality after emergent TAVI reported in these original studies showed inconsistent trends. Our study pooled data derived from 14 articles finding the emergent TAVI in decompensated AS had higher risk for mortality before discharge and within 30 days and 1 year, in comparison with those stable AS undergoing elective TAVI. This reflects that emergent TAVI does not show absolute advantage in acute decompensation scenarios, although, in terms of some postoperative complications, emergent TAVI can achieve similar results as elective TAVI. As a more rapid and convenient rescue measure, BAV is also used as a buffer for decision-making, allowing patients to be reassessed in a more stable situation [20]. According to a recent single-center cohort study [21], there was no significant difference in 1-year mortality between patients receiving emergent TAVI and patients receiving TAVI or SAVR after emergent BAV. Further research should be conducted to individualize perioperative management to identify situations in which emergency TAVI benefits more and situations in which expanded use of BAV is warranted. Nowadays, the indications of TAVI are expanding [22] and TAVI is growing rapidly worldwide [23]. This may lead to longer wait times for TAVI patients to undergo surgery and greater risk for interval decompensation [6]. These findings emphasize the importance of optimizing the time from diagnosis to surgery, timely and correctly identifying the proneness of decompensated AS, and avoiding undesirable intervention conditions.

Our study showed that the incidence of bleeding and major bleeding after emergent TAVI increased, and major bleeding or life-threatening bleeding was associated with significant increase in the 30-day mortality [24]. The higher prevalence of bleeding might be explained by the high incidence of atrial fibrillation (AF) at baseline [25, 26] and higher incidence of AKI after emergent TAVI [27]. The increased incidence of baseline atrial fibrillation may be related to left ventricular pressure overload caused by AS [28]. Antithrombotic regimens, commonly administered to patients with atrial fibrillation, might be a crucial cause of the increased bleeding after TAVI [29]. Actually, a large proportion of patients required mechanical circulatory support and/or mechanical ventilation at the time of TAVI [30], which complicated the use of antithrombotic agents and increased the occurrence rate of bleeding.

The present study established that AKI and dialysis were more common after emergent TAVI. It was concerned that AKI and dialysis after TAVI impaired both early (in-hospital and 30-day) and late survival [27, 31, 32]. The risk factors of AKI were multifactorial. We observed preoperative risk factors [33] such as elevated baseline creatine and higher STS score in emergent TAVI patients. Patients with emergent TAVI might receive CT angiography and cardiac catheterization within a short time before surgery [10]. And contrast medium was considered an important factor of renal injury during TAVI [34]. Bleeding and postprocedural AR, which were more common in emergent TAVI patients, were also reported to be associated with AKI after TAVI [35]. There were no consensuses on AKI prevention in the TAVI patients. Furosemide-induced diuresis with matched isotonic intravenous hydration by the RenalGuard system is the effective device to reduce the happening of AKI in TAVI [36]. It helps to shorten the contact time between contrast medium and tubular cells without overloading the patient's volume [37]. There were also some case reports of patients who underwent TAVI with minimal contrast media during intraoperative and preoperative preparation. Arrigo et al. [38] carried out TAVI with the single contrast injection to ensure correct position of the pigtail catheter at the level of annulus. Then, the pigtail served as a marker for valve deployment. In a case report of Higuchi et al. [39], the valve was positioned using the calcified valve as a landmark, in which no contrast medium was used during TAVI. Although these individual cases cannot be generalized to all patients due to their limitations, they also provide ideas for preventing AKI in high-risk TAVI patients.

There are some limitations in our study. Firstly, some of our results had significant heterogeneity. Although we have used a variety of methods, we still cannot find the exact source of heterogeneity in some parts. Besides, our sensitivity analysis still demonstrated the robustness of a substantial part of our result. These parts of the results should be treated dialectically. Secondly, the studies in our meta-analysis were retrospective or prospective observational design. Confounding factors that were not included in the study cannot be excluded. Thirdly, despite our efforts to exclude overlapping data, there may still be overlapping data in our study due to inclusion of TVT studies. Finally, some abstracts were excluded due to the inability to obtain computable data, which had no definite impact on our study.

5. Conclusions

This meta-analysis investigated the differences in postoperative mortality and perioperative events between emergent and elective TAVI patients. Our study demonstrated that emergent TAVI was associated with increased 30-day, in-hospital, and 1-year mortality. Emergent TAVI increased the incidence of AKI and dialysis, bleeding, and major bleeding after TAVI; however, vascular complications, major vascular complications, PPM placement, cerebrovascular events, and moderate to severe PVL did not increase. The current results show that emergent TAVI is not able to achieve the same excellent results as elective TAVI. In the case of emergency, the decision-making of emergency TAVI should be individualized to avoid the occurrence of complications that may lead to the poor prognosis of emergent TAVI.

Acknowledgments

The study has received funding from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 11902211 accorded to Junli Li) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81900348 accorded to Yanbiao Liao).

Contributor Information

Yanbiao Liao, Email: liaoyanbiao@foxmail.com.

Mao Chen, Email: hmaochen@foxmail.com.

Data Availability

The figures and tables data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contributions

Ruochen Shao and Junli Li have contributed equally to this work.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure S1: Galbraith radial plot (a), cumulative meta-analysis (b), and sensitivity analysis (c) showing the contribution of results from the 11 studies to heterogeneity. Forest plot showing the 30-day mortality after removing an article with heterogeneity (d). Supplemental Figure S2: Cumulative meta-analysis (a) and sensitivity analysis (b) showing the contribution of results from the 7 studies to heterogeneity. Forest plot showing the in-hospital mortality after removing an article with heterogeneity (c). Galbraith radial plot (d), cumulative meta-analysis (e), and sensitivity analysis (f) showing the contribution of results from the 9 studies to heterogeneity. Supplemental Figure S3: Sensitivity analysis (a) showing the contribution of results from the 9 studies to heterogeneity. Forest plot showing the incidence of AKI after removing an article with heterogeneity (b). Sensitivity analysis (c) showing the contribution of results from the 7 studies to heterogeneity. Sensitivity analysis (d) showing the contribution of results from the 6 studies to heterogeneity. Forest plot showing the incidence of major vascular complications after removing an article with heterogeneity (e). Sensitivity analysis (f) showing the contribution of results from the 5 studies to heterogeneity. Forest plot showing the incidence of device success after removing an article with heterogeneity (g). Supplemental Table 1: Univariate meta-regression on 30-day mortality of emergent TAVI and selective TAVI. Supplemental Table 2: Univariate meta-regression on mortality during hospitalization of emergent TAVI and selective TAVI. Supplemental Table 3: Univariate meta-regression on 1-year mortality of emergent TAVI and selective TAVI. .

References

- 1.Bocchino P. P., Angelini F., Alushi B., et al. Transcatheter aortic valve replacement in young low-risk patients with severe aortic stenosis: a review. Frontiers in cardiovascular medicine . 2020;7 doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2020.608158.608158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hu P., Liu X.-B., Liang J., et al. A hospital-based survey of patients with severe valvular heart disease in China. International Journal of Cardiology . 2017;231:244–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.11.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nagao K., Taniguchi T., Morimoto T., et al. Acute heart failure in patients with severe aortic stenosis- insights from the CURRENT AS registry. Circulation Journal . 2018;82(3):874–885. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-17-0610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frerker C., Schewel J., Schlüter M., et al. Emergency transcatheter aortic valve replacement in patients with cardiogenic shock due to acutely decompensated aortic stenosis. EuroIntervention . 2016;11(13):1530–1536. doi: 10.4244/eijy15m03_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pino J. E., Sundaravel S., Ramos-Tuarez F., et al. Outcomes in patients with acutely decompensated heart failure undergoing emergent transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Catheterization and Cardiovascular Interventions . 2018;91:S203–S4. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen K., Polcari K., Michiko T., et al. Outcomes of urgent transcatheter aortic valve replacement in patients with acute decompensated heart failure: a single-center experience. Cureus . 2020;12(9) doi: 10.7759/cureus.10425.e10425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bianco V., Habertheuer A., Kilic A., et al. Urgent transcatheter aortic valve replacement may be performed with acceptable long-term outcomes. Journal of Cardiac Surgery . 2021;36(1):206–215. doi: 10.1111/jocs.15195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ichibori Y., Li J., Patel T., et al. Short-Term and long-term outcomes of patients undergoing urgent transcatheter aortic valve replacement under a minimalist strategy. Journal of Invasive Cardiology . 2019;31(2):E30–E36. doi: 10.25270/jic/18.00221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elbaz-Greener G., Yarranton B., Qiu F., et al. Association between wait time for transcatheter aortic valve replacement and early postprocedural outcomes. J Am Heart Assoc . 2019;8(1) doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.010407.e010407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kolte D., Khera S., Vemulapalli S., et al. Outcomes following urgent/emergent transcatheter aortic valve replacement: insights from the STS/ACC TVT registry. JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions . 2018;11(12):1175–1185. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2018.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Angeras O., Petursson P., Gabel J., et al. Short and long term prognosis of patients undergoing urgent TAVI. European Heart Journal . 2017;38:p. 673. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx504.p3295. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Landes U., Orvin K., Codner P., et al. Urgent transcatheter aortic valve implantation in patients with severe aortic stenosis and acute heart failure: procedural and 30-day outcomes. Canadian Journal of Cardiology . 2016;32(6):726–731. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2015.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kabahizi A., Sheikh A. S., Williams T., et al. Elective versus urgent in-hospital transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Catheterization and Cardiovascular Interventions . 2021;98(1):170–175. doi: 10.1002/ccd.29638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Enta Y., Miyasaka M., Taguri M., et al. Patients’ characteristics and mortality in urgent/emergent/salvage transcatheter aortic valve replacement: insight from the OCEAN-TAVI registry. Open Heart . 2020;7(2) doi: 10.1136/openhrt-2020-001467.e001467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elbadawi A., Elgendy I. Y., Mentias A., et al. Outcomes of urgent versus nonurgent transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Catheterization and Cardiovascular Interventions . 2020;96(1):189–195. doi: 10.1002/ccd.28563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alnasser S., Peterson M. D., Sharma S. S., Cheema A. Safety and efficacy of urgent transcatheter aortic valve replacement in patients admitted with decompensated heart failure. Journal of the American College of Cardiology . 2014;64(11):p. B202. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.07.762. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berkovitch A., Segev A., Finkelstein A., et al. Procedural and remote outcome among patients undergoing urgent trans-catheter aortic valve implantation. European Heart Journal . 2020;41(SUPPL 2):p. 2586. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/ehaa946.2586. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leon M. B., Smith C. R., Mack M., et al. Transcatheter aortic-valve implantation for aortic stenosis in patients who cannot undergo surgery. New England Journal of Medicine . 2010;363(17):1597–1607. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1008232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kornowski R. Appraisal of urgent transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Catheterization and Cardiovascular Interventions . 2020;96(1):196–197. doi: 10.1002/ccd.29075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bongiovanni D., Kühl C., Bleiziffer S., et al. Emergency treatment of decompensated aortic stenosis. Heart . 2018;104(1):23–29. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2016-311037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ali N., Patel P., Wahab A., et al. A cohort study examining urgent and emergency treatment for decompensated severe aortic stenosis. Journal of Cardiovascular Medicine . 2021;22(2):126–132. doi: 10.2459/jcm.0000000000001112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rahhab Z., El Faquir N., Tchetche D., et al. Expanding the indications for transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Nature Reviews Cardiology . 2020;17(2):75–84. doi: 10.1038/s41569-019-0254-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cubero-Gallego H., Dam C., Meca J., Avanzas P. Transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR): expanding indications to low-risk patients. Annals of Translational Medicine . 2020;8(15):p. 960. doi: 10.21037/atm.2020.03.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Borz B., Durand E., Godin M., et al. Incidence, predictors and impact of bleeding after transcatheter aortic valve implantation using the balloon-expandable Edwards prosthesis. Heart . 2013;99(12):860–865. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2012-303095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huczek Z., Kochman J., Grygier M., et al. Pre-procedural dual antiplatelet therapy and bleeding events following transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) Thrombosis Research . 2015;136(1):112–117. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2015.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang J., Yu W., Jin Q., et al. Risk factors for post-TAVI bleeding according to the VARC-2 bleeding definition and effect of the bleeding on short-term mortality: a meta-analysis. Canadian Journal of Cardiology . 2017;33(4):525–534. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2016.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ma M., Gao W.-d., Gu Y.-F., Wang Y.-S., Zhu Y., He Y. Clinical effects of acute kidney injury after transcatheter aortic valve implantation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Internal and Emergency Medicine . 2019;14(1):161–175. doi: 10.1007/s11739-018-1935-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tarantini G., Mojoli M., Urena M., Vahanian A. Atrial fibrillation in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation: epidemiology, timing, predictors, and outcome. European Heart Journal . 2017;38(17):1285–1293. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Czerwińska-Jelonkiewicz K., Witkowski A., Dąbrowski M., et al. Antithrombotic therapy - predictor of early and long-term bleeding complications after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Archives of Medical Science . 2013;9(6):1062–1070. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2013.39794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang H., Kovach C. P., Bell S., et al. Outcomes of emergency transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Journal of Interventional Cardiology . 2019;2019 doi: 10.1155/2019/7598581.7598581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haase-Fielitz A., Altendeitering F., Iwers R., et al. Acute kidney injury may impede results after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Clinical Kidney Journal . 2020;14(1):261–268. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfaa179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sgura F. A., Arrotti S., Magnavacchi P., et al. Kidney dysfunction and short term all-cause mortality after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. European Journal of Internal Medicine . 2020;81:32–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2020.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ram P., Mezue K., Pressman G., Rangaswami J. Acute kidney injury post-transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Clinical Cardiology . 2017;40(12):1357–1362. doi: 10.1002/clc.22820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adachi Y., Yamamoto M., Shimura T., et al. Late adverse cardiorenal events of catheter procedure-related acute kidney injury after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. The American Journal of Cardiology . 2020;133:89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2020.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liao Y.-b., Deng X.-x., Meng Y., et al. Predictors and outcome of acute kidney injury after transcatheter aortic valve implantation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. EuroIntervention . 2017;12(17):2067–2074. doi: 10.4244/eij-d-15-00254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barbanti M., Gulino S., Capranzano P., et al. Acute kidney injury with the RenalGuard system in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement: the PROTECT-TAVI trial (PROphylactic effecT of furosEmide-induCed diuresis with matched isotonic intravenous hydraTion in transcatheter aortic valve implantation) JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions . 2015;8(12):1595–1604. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2015.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morcos M., Burgdorf C., Vukadinivikj A., et al. Kidney injury as post-interventional complication of TAVI. Clinical Research in Cardiology . 2021;110(3):313–322. doi: 10.1007/s00392-020-01732-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arrigo M., Maisano F., Haueis S., Binder R. K., Taramasso M., Nietlispach F. Transcatheter aortic-valve implantation with one single minimal contrast media injection. Catheterization and Cardiovascular Interventions . 2015;85(7):1248–1253. doi: 10.1002/ccd.25799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Higuchi R., Tobaru T., Hagiya K., et al. Renoprotective transcatheter aortic valve implantation without contrast media. International Heart Journal . 2018;59(6):1469–1472. doi: 10.1536/ihj.17-588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure S1: Galbraith radial plot (a), cumulative meta-analysis (b), and sensitivity analysis (c) showing the contribution of results from the 11 studies to heterogeneity. Forest plot showing the 30-day mortality after removing an article with heterogeneity (d). Supplemental Figure S2: Cumulative meta-analysis (a) and sensitivity analysis (b) showing the contribution of results from the 7 studies to heterogeneity. Forest plot showing the in-hospital mortality after removing an article with heterogeneity (c). Galbraith radial plot (d), cumulative meta-analysis (e), and sensitivity analysis (f) showing the contribution of results from the 9 studies to heterogeneity. Supplemental Figure S3: Sensitivity analysis (a) showing the contribution of results from the 9 studies to heterogeneity. Forest plot showing the incidence of AKI after removing an article with heterogeneity (b). Sensitivity analysis (c) showing the contribution of results from the 7 studies to heterogeneity. Sensitivity analysis (d) showing the contribution of results from the 6 studies to heterogeneity. Forest plot showing the incidence of major vascular complications after removing an article with heterogeneity (e). Sensitivity analysis (f) showing the contribution of results from the 5 studies to heterogeneity. Forest plot showing the incidence of device success after removing an article with heterogeneity (g). Supplemental Table 1: Univariate meta-regression on 30-day mortality of emergent TAVI and selective TAVI. Supplemental Table 2: Univariate meta-regression on mortality during hospitalization of emergent TAVI and selective TAVI. Supplemental Table 3: Univariate meta-regression on 1-year mortality of emergent TAVI and selective TAVI. .

Data Availability Statement

The figures and tables data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.