Abstract

Previous work described Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato group DN127 as a new genospecies, Borrelia bissettii, and prompted the present study to identify the Borrelia spp. that exist in northern Colorado. To determine the genospecies present, we analyzed two specific intergenic spacer regions located between the 5S and 23S and the 16S and 23S ribosomal genes. Phylogenetic analysis of the derived sequences clearly demonstrated that these isolates, originating from rodents captured in the foothills of northern Colorado, diverged from B. burgdorferi sensu stricto by 5 to 5.5% and were members of the new genospecies B. bissettii.

Lyme disease is the most common vector-borne disease in the United States (1), and it causes a spectrum of clinical symptoms, including erythema migrans, migratory joint and muscle pain, debilitating malaise, neurologic symptoms, and chronic arthritis (9). The disease is caused by the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato, which is transmitted by Ixodes scapularis ticks in the eastern and upper midwestern United States and by Ixodes pacificus in the far western United States. At present, 10 different Borrelia species have been described within the B. burgdorferi sensu lato complex, with only 3 found in North America: B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, B. andersonii, and B. bissettii (9). Presently, B. burgdorferi sensu stricto is the only member of the complex known to be associated with Lyme disease in North America. Previous studies determined an enzootic cycle of B. burgdorferi in northern Colorado which is maintained by the Ixodes spinipalpis tick and its rodent hosts, Neotoma mexicana and Peromyscus difficilis (4). Tick and rodent isolates were characterized as B. burgdorferi sensu lato, based on PCR, restriction enzyme digestion, polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and immunoblotting analysis (4). Further examination of portions of the flagellin, the 66-kDa protein, and the outer surface protein A genes demonstrated that the Colorado strains were most similar to isolates from California (5). Subsequent work by Postic et al. proposed that some isolates in California were divergent enough to warrant classification as a new genospecies, B. bissettii. Postic et al. utilized two specific intergenic spacer regions to analyze the polymorphism of the California strains (6). These intergenic spacers lie between the 5S and 23S (rrf-rrl) and the 16S and 23S (rrl-rrs) ribosomal genes. Sequence analysis of these regions was found to be highly informative in differentiating the genospecies within the B. burgdorferi sensu lato complex (2). We took advantage of these regions to analyze rodent strains circulating in enzootic cycles in Colorado.

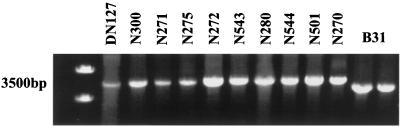

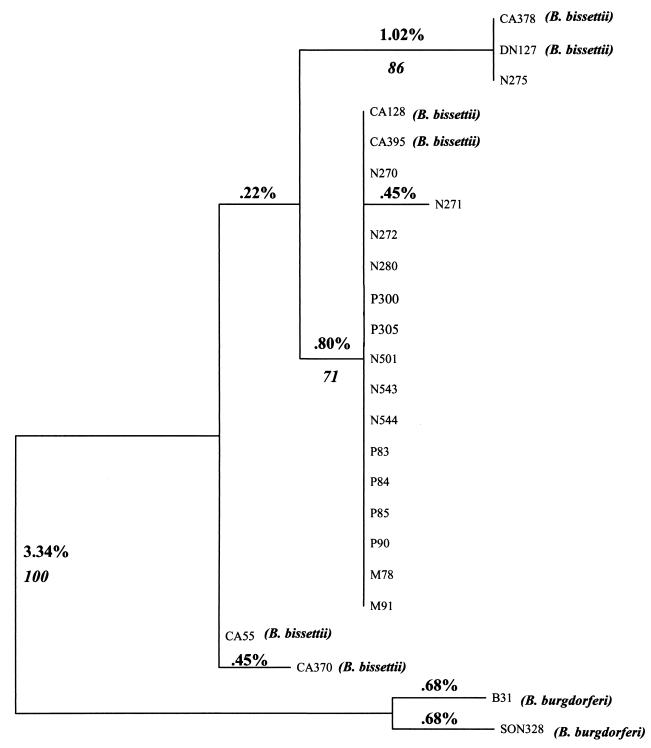

Borrelia was isolated from rodents captured in the foothills of northern Colorado, as previously described (4). The sites predominantly consisted of rock outcroppings with various low-lying brush and grasses, on an east-facing slope at an approximate elevation of 1,560 m. The rodent species examined included Neotoma mexicana, Peromyscus difficilis, Peromyscus maniculatus, and Microtus ochrogaster. I. spinipalpis larvae and nymphs were the only ticks found on captured rodents. The isolates chosen for analysis were representative of those cultured from 189 infected rodents. Borrelia strains were cultured from the rodents by ear tissue biopsies, as previously described (4), and stored at −70°C in 30% glycerol. All enzootic Colorado Borrelia cultures were passed by in vitro cultivation fewer than three times. Borrelial genomic DNA was extracted by using a DNA minikit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, Calif.), and amplification of the large spacer (rrl-rrs) region was achieved by using primers S15 (5′-GGGCCTTGTACACACCGCCC-3′) and INS4 (5′-AGCTCCTAGGCATTCACCAT-3′) (6). The PCR protocol utilized 2.5 μl of DNA added separately to a 50-μl reaction volume containing 1× PCR buffer (Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 2.5 U of Taq polymerase (Amplitaq; Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems), and 100 pmol of each primer. PCRs were run on a PE 2400 thermal cycler (Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems) with a protocol previously described by Postic et al. (6). Briefly, 30 amplification cycles were performed, including denaturation at 93°C for 15 s, simultaneous annealing and extension at 60°C for 8 min, and a final extension step at 60°C for 10 min. The amplicons were then visualized on an ethidium bromide-stained 0.6% SeaKem GTG (FMC BioProducts, Rockland, Maine) agarose gel. Amplification of the rrl-rrs region of representative samples of Borrelia spp. isolated from Colorado rodents generated a 3,500-bp product equivalent in size to that of the DN127 strain and approximately 250 bp larger than that generated by B. burgdorferi sensu stricto (Fig. 1). Previous work had demonstrated that gel migration of these rrl-rrs spacer PCR products distinguished sensu stricto strains from B. bissettii (6). To confirm these results, the small spacer (rrf-rrl) region was amplified by using primers A (5′-ATTACCCGTATCTTTGGC-3′) and D (5′-TCAATAAATGTTTGCTTCTC-3′) (6). Again, 2.5 μl of DNA was added separately to a 50-μl reaction volume prepared as described above, utilizing the protocol described previously by Postic et al. (6). The resulting 360-bp amplicons were gel purified and sequenced by using primers INS1 (5′-GAAAAGAGGAAACACCTGTT-3′) and INS4 (5′-AGCTCCTAGGCATTCACCAT-3′) (6). The sequencing reaction was prepared by adding 50 ng of purified amplicon and 3.2 pmol of primer to a dye terminator cycle sequencing reaction (Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems). Sample reactions were then analyzed in an ABI Prism 377 DNA sequencer (Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems). Reference sequences used to construct the phylogenetic tree were from CA378 (accession number AJ006367), CA55 (L30124), CA370 (AJ006364), CA128 (AJ006365), CA395 (AJ006363), B31 (L30127), and SON328 (AJ006512). Sequences were aligned with MegAlign (DNASTAR, Inc., Madison, Wis.) by using the Clustal algorithm, and aligned sequences were then transferred to PAUP (Sinauer Associates, Inc., Sutherland, Mass.) for phylogenetic analysis. To create trees, heuristic searches were performed using parsimony, likelihood, and distance methods. Trees generated by all three methods were equivalent in our studies. Furthermore, a bootstrap analysis was run with 500 replications. Phylogenetic analysis confirmed that all but one of the Colorado strains were identical to the CA395 and CA128 (Fig. 2) strains of Borrelia, which were classified as B. bissettii by Postic et al. (6). The remaining Colorado strain was most analogous with the DN127 strain, the prototypical B. bissettii isolate. The Colorado strains diverged from B. burgdorferi sensu stricto by 5.0 to 5.5%. Additionally, bootstrap analysis demonstrated that the Colorado strains clustered with DN127 and separately from B. burgdorferi sensu stricto in 100% of the generated trees.

FIG. 1.

PCR amplification of the rrl-rrs region, demonstrating a 3,500-bp amplicon for prototypical B. bissettii (strain DN127) and numerous Colorado strains, as designated. B31 = B. burgdorferi sensu stricto strain B31 (low passage).

FIG. 2.

Maximum-parsimony phylogenetic tree generated using PAUP. Branches indicate the percent divergence of the rrf-rrl sequence. Italicized numbers indicate parsimony bootstrap scores for the branch. N before numbers, Neotoma mexicana; P, Peromyscus (P. maniculatus, P300 and P305; P. difficilis, P83 to P85 and P90); M, Microtus ochrogaster.

Although Colorado isolates of Borrelia were previously described as B. burgdorferi sensu lato (4, 5), these strains had not been further characterized as to genospecies. This study established that Colorado strains of Borrelia fall into the genospecies designated B. bissettii. Phylogenetic analysis of the rrf-rrl spacer region demonstrated that Colorado strains diverge significantly from B. burgdorferi and cluster closely with B. bissettii. The size of the rrl-rrs spacer region, which previously had been shown to be an appropriate tool for distinguishing among Borrelia species (5, 6), also confirmed that these Colorado strains are most analogous with other B. bissettii strains. This updates an earlier study by Norris et al. (5), which concluded that Colorado strains are most similar to California strains. In addition, the present study identified previously undescribed rodent hosts for B. bissettii, including isolates derived from P. maniculatus (P300 and P305) and M. ochrogaster (M78 and M91) (Fig. 2). Isolates previously had been identified in I. scapularis, I. spinipalpis, and I. pacificus ticks (6). Moreover, B. bissettii has now been identified in widely dispersed geographical regions in the United States, including northern California, northern Colorado, New York, Georgia, and Florida (3, 6). B. bissettii is probably more widely distributed geographically than is now known, although further studies are needed to make this determination.

European DN127 type strains have been isolated from humans displaying clinical symptoms associated with Lyme borreliosis (7, 8). Additionally, different genospecies of Borrelia in Europe are associated with differing spectrums of clinical diseases (6). It is therefore possible that some cases of Lyme disease in the United States may be caused by B. bissettii. Thus, distinguishing human infections caused by B. burgdorferi sensu stricto from those caused by B. bissettii may lend insight into the reasons for the varied symptomatology seen in North America. Finding such a correlation between disease entities and genospecies may generate a better understanding of the pathology of Lyme borreliosis.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences of the rrf-rrl spacer regions have been submitted to GenBank and assigned accession numbers AF230079 to AF230094.

Acknowledgments

We thank D. Postic of the Pasteur Institute's Unité de Bactériologie Moléculaire et Médicale for helpful discussions regarding PCR protocols; R. Lane from the Department of Environmental Science, Policy and Management, Insect Biology Division, University of California, Berkeley, for contributing several reference strains; and W. Probert of the California State Department of Health for providing low-passage DN127 as a positive control for our analyses.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Lyme disease—United States. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1997;46:531–535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liveris D, Gazumyan A, Schwartz I. Molecular typing of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato by PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:589–595. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.3.589-595.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mathiesen D A, Oliver J H, Jr, Kolbert C P, Tullson E D, Johnson B J B, Campbell G L, Mitchell P D, Reed K D, Telford III S R, Anderson J F, Lane R S, Persing D H. Genetic heterogeneity of Borrelia burgdorferi in the United States. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:98–107. doi: 10.1093/infdis/175.1.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maupin G O, Gage K L, Piesman J, Montenieri J, Sviat S L, VanderZanden L, Happ C M, Dolan M, Johnson B J B. Discovery of an enzootic cycle of Borrelia burgdorferi in Neotoma mexicana and Ixodes spinipalpis from northern Colorado, an area where Lyme disease is nonendemic. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:636–643. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.3.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Norris D E, Johnson B J B, Piesman J, Maupin G O, Clark J L, Black W C. Population genetics and phylogenetic analysis of Colorado Borrelia burgdorferi. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;60:699–707. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.60.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Postic D, Ras N M, Lane R S, Hendson M, Baranton G. Expanded diversity among Californian Borrelia isolates and description of Borrelia bissettii sp. nov. (formerly Borrelia group DN127) J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:3497–3504. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.12.3497-3504.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strle F, Picken R N, Cheng Y, Cimperman J, Maraspin V, Lotric-Furlan S, Ruzic-Sabljic E, Picken M M. Clinical findings for patients with Lyme borreliosis caused by Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato with genotypic and phenotypic similarities to strain 25015. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:273–280. doi: 10.1086/514551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang G, van Dam A P, Dankert J. Phenotypic and genetic characterization of a novel Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato isolate from a patient with Lyme borreliosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3025–3028. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.9.3025-3028.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang G, van Dam A P, Schwartz I, Dankert J. Molecular typing of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato: taxonomic, epidemiological, and clinical implications. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12:633–653. doi: 10.1128/cmr.12.4.633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]