Abstract

Chorioamnionitis or intra-uterine inflammation is a frequent cause of preterm birth. Chorioamnionitis can affect almost every organ of the developing fetus. Multiple microbes have been implicated to cause chorioamnionitis, but “sterile” inflammation appears to be more common. Eradication of micro-organisms has not been shown to prevent the morbidity and mortality associated with chorioamnionitis as inflammatory mediators account for continued fetal and maternal injury. Mounting evidence now supports the concept that the ensuing neonatal immune dysfunction reflects the effects of inflammation on immune programming during critical developmental windows, leading to chronic inflammatory disorders as well as vulnerability to infection after birth. A better understanding of microbiome alterations and inflammatory dysregulation may help develop better treatment strategies for infants born to mothers with chorioamnionitis.

Introduction

In 2015, 9.7% of all births in the US were preterm births,1 which contributed to 75% of perinatal mortality and 50% of the long-term morbidity.2 Chorioamnionitis triggers 40%−70% of prematurity, with the incidence higher for lower gestational ages.2–5 Acute chorioamnionitis or intra-uterine inflammation (IUI) implies that a pregnant woman has an inflammatory or an infectious disorder of the chorion, amnion, or both, which in turn, suggests that the mother and her fetus may be at an increased risk for developing serious complications.6 Robust maternofetal proinflammatory immune responses triggered in chorioamnionitis result in early pregnancy termination by spontaneous preterm birth to preserve the life of the mother, though at the expense of the vulnerable fetus.7

While microorganisms are frequently associated with chorioamnionitis, it can occur as “sterile” intra-amniotic inflammation in the absence of demonstrable microorganisms and is induced by danger signals released under conditions of cellular stress, injury, or death.8 Thus, acute chorioamnionitis is evidence of intra-amniotic inflammation and not necessarily intra-amniotic infection. Intra-amniotic infection and chorioamnionitis are commonly used interchangeably; however, these two conditions are not the same. Sterile inflammation (e.g. mediated via damage-associated molecular patterns or DAMPs),9 environmental pollutants,9–11 cigarette smoke,12 and other toxicants have also been implicated in chorioamnionitis. Sterile inflammation is more frequent than intra-amniotic infection (i.e. microbe-associated intra-amniotic inflammation) in patients with preterm labor with intact membranes, preterm premature rupture of membranes, and an asymptomatic short cervix.8,13–15 This inflammatory infiltrate is induced by the maternal inflammatory response from the intervillous space and decidua, as well as the fetal inflammatory response from the vessels of the umbilical cord and chorionic plate

The inflammatory complications associated with chorioamnionitis have been well described, and these effects may last into adulthood.16 Increasing evidence supports the concept that the ensuing neonatal immune dysfunction reflects the effects of inflammation on immune programming during critical developmental windows, leading to chronic inflammatory disorders as well as vulnerability to infection after birth.17

In this review, we discuss the microbiology and inflammatory pathways involved in chorioamnionitis followed by a brief discussion of the neonatal complications and management of chorioamnionitis.

Definitions & Staging of Chorioamnionitis

Clinical chorioamnionitis has been defined as a broad clinical syndrome with any combination of fever, maternal or fetal tachycardia, uterine tenderness, foul-smelling amniotic fluid, or elevated white blood cell (WBC) count. However, the presence of one (or even more than one) of these signs and symptoms does not necessarily indicate intra-uterine/intra-amniotic inflammation – or that histopathologic chorioamnionitis is present. In a study of patients with preterm clinical chorioamnionitis, 24% had no evidence of either intra-amniotic infection or intra-amniotic inflammation, and 66% had negative amniotic fluid cultures. Interestingly, only 12% of patients with acute histological chorioamnionitis at term had detectable microorganisms in the placenta.18 Patients without microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity or intra-amniotic inflammation had lower rates of adverse outcomes than those with microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity and/or intra-amniotic inflammation.19

The term chorioamnionitis has been loosely used to label a heterogeneous array of conditions characterized by infection and inflammation or both, with a consequent marked variation in clinical management for mothers with chorioamnionitis and their newborns. Due to the imprecise definition and to the variable clinical manifestations, the expert panel led by NICHD proposed to replace the term chorioamnionitis with a more general, descriptive term, “intrauterine inflammation or infection or both,” abbreviated as “Triple I.” The panel proposed a classification for Triple I and recommended approaches to evaluation and management of pregnant women and their newborns with a diagnosis of Triple I.20 In these guidelines, fever alone during labor is classified separately, because excluding fever as a prerequisite for the criteria of clinical chorioamnionitis increases sensitivity for the identification of neonatal sepsis.21 Suspected Triple I” is defined as fever with one or more of the following symptoms: leukocytosis, fetal tachycardia, or purulent cervical discharge. To be confirmed, “suspected Triple I” should be accompanied by evidence of amniotic fluid infection (e.g., positive gram stain for bacteria, low amniotic fluid glucose, high WBC count in the absence of a bloody tap, and/or positive amniotic fluid culture results) or histopathological infection/inflammation in the placenta, fetal membranes or the umbilical cord vessels.20

Histopathological chorioamnionitis is defined as diffuse infiltration of neutrophils into the chorioamniotic membranes.22 If it affects the villous tree, this represents acute villitis. Inflammatory processes involving the umbilical cord (umbilical vein, umbilical artery, and the Wharton’s jelly) are referred to as acute funisitis. These findings represent the histological evidence of the fetal inflammatory response syndrome (FIRS).23 Neutrophils are not normally present in the chorioamniotic membranes and migrate from the decidua into the membranes in cases of acute chorioamnionitis. Thus, the neutrophils infiltrating the choriodecidua are maternal in origin, while neutrophils in the amniotic fluid are mixture of fetal and maternal origin, and those infiltrating the umbilical cord are of fetal origin.24

Although several grading systems have been used to define the severity of chorioamnionitis, the criteria developed by Redline et al,22 and recommended by the Amniotic Fluid Infection Nosology Committee of the Perinatal Section of the Society for Pediatric Pathology, are the most widely accepted Herein, acute inflammatory lesions of the placenta are classified into two categories: maternal inflammatory response and fetal inflammatory response. The term stage (Stages 1 to 3) refers to the progression of the process based on the anatomical regions infiltrated by neutrophils; the term grade refers to the intensity of the acute inflammatory process at a particular site (Grade 1 to 3).

Microbiology of chorioamnionitis

Acute chorioamnionitis is often thought to be due to ascending infection - diffuse ascending colonization of the endometrial-chorionic potential space with extension into the fetal membranes, the amniotic fluid, and ultimately the fetus.25 This hypothesis was proposed as a result of the association of bacteria of the urogenital tract, such as Mycoplasma spp, Ureaplasma spp, and Group B Streptococcus (GBS), with chorioamnionitis, and with the colonization of placental/fetal membranes.13,26–31 Other organisms such as Gardenella vaginalis, E. coli, and fungi such as Candida have been associated with chorioamnionitis.3,32–34 Polymicrobial infection is seen in about 30% of the cases.35

However, the presence of bacteria is not necessarily indicative of infection. The vaginal microbiome changes during pregnancy.36 While currently controversial due to long staining evidence supporting sterility of the womb, evidence is mounting that the fetus does not exist in a sterile environment and the placental microbiome is likely similar to the oral microbiome.37 The presence of live microbes in fetal organs during pregnancy have broader implications toward the establishment of immune competency and priming before birth.38 The microbiome of the chorionamnion changes with chorioamnionitis to more urogenital and mouth-resembling commensal bacterial.30 Decreased Lactobacillus spp. with increased Ureaplasma spp. in the vagina predicts preterm birth.39,40 Animal studies support the correlation between Ureaplasma presence and preterm birth.41 The association between the placental and oral microbiomes provides a potential explanation for the presence of commensal oral bacteria (such as Streptococcus and Fusobacterium spp.) in chorioamnionitis via the hematogenous spread of bacteria during pregnancy into the amniotic cavity.42 Although the placental membrane microbiota are altered in histologic chorioamnionitis, there are no observable impacts with either betamethasone or antibiotic therapy.39 In addition, various TORCH pathogens, including Toxoplasma gondii, other (Listeria monocytogenes, Treponema pallidum, parvovirus, HIV, varicella zoster virus, among others), Rubella, Cytomegalovirus, and Herpesviruses 1 and 2, and more recently, Zika virus, as well as Plasmodium spp., have been implicated in chorioamnionitis.43–45 Intra-amniotic infection with fungi has also been found in women who become pregnant while using intrauterine contraceptive devices.46 In contrast to the ascending infections causing inflammation primarily in the choriodecidua and amnion, organisms invading through the hematogenous route cause inflammation primarily in the placental villi and intervillous space.47

Experimental evidence exists that bacteria can cross intact membranes, and rupture of the membranes is therefore not necessary for bacteria to reach the amniotic cavity.48 Thus, intra-amniotic infection has been documented in patients with preterm labor with intact membranes as well as in preterm premature rupture of the membranes and cervical insufficiency.13,25,49

Immunology/cytokines associated with chorioamnionitis

The inflammatory mediators during chorioamnionitis are implicated as causative agents of prematurity.50 Bacterial colonization of the amniotic fluid without inflammation is relatively benign. Intra-amniotic inflammation is associated with adverse perinatal outcomes whether or not microbes are detected.32 This implies that inflammation, regardless of etiology, is the primary driver of morbidity seen with chorioamnionitis.

Currently available therapies for chorioamnionitis and/or preterm labor rely on antibiotics, progesterone, and antenatal corticosteroids.20,51 However, these treatments are not generally effective, and there are many adverse effects.52,53 Antibiotics, often fail to prevent chorioamnionitis-associated morbidities,54,55 due to persistent inflammatory mediators that account for fetal and maternal injury.56 Exposure to chorioamnionitis activates the neonatal immune system in utero with potentially long-term health consequences.57

The amniotic membrane safeguards the maturing fetus against exposure to pathogenic organisms, while also providing an immunologically privileged site designed to protect the allogenic fetus from maternal rejection. Alteration in this safeguard mechanism leads to chorioamnionitis.58 Microbial invasion or introduction of inflammatory stimuli into the amniotic cavity induces a robust local inflammatory response. In the early stages of chorioamnionitis, maternal immune responses dominate, infiltrating the fetal membranes.16 The elevated gradient of chemokine concentrations that is established across the chorio-amniotic membranes and the decidua favors the diffuse infiltration of maternal neutrophils into the chorio-amniotic membranes.59 In the absence of microorganisms, danger signals released by cells under stress conditions or cell death can induce intra-amniotic inflammation.60,61 Conversely, infection without a fetal/maternal inflammatory response may not cause labor and preterm delivery.19 If the infectious or inflammatory process progresses, fetal leukocytes then infiltrate leading to a dramatic increase in the concentrations of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, IL-18 and chemokines such as well as chemokines such as IL-8, CXCL6, CXCL10.25 This condition is known as FIRS.7

FIRS has been classically defined by an elevated cord plasma IL-6 concentration which is a critical marker of intrauterine inflammation and a predictor of preterm birth.7,62 The prevalence of FIRS, defined by fetal plasma IL-6 level > 11 pg/mL, is about 50%, and these infants are at a higher rate of severe neonatal morbidity.7 Recently, IL-17A has also been shown to be a vital component in the initiation of FIRS and a potential contributor to the later development of chronic conditions caused by fetal exposure to in utero inflammatory and/or infectious processes.63,64 IL-17A is an important component of host immune responses that target and eliminate extracellular pathogens including Gram-positive, Gram-negative, and fungal microbes.65,66 Compared to adults, newborns have lower baseline levels of IL-17A, which may diminish their ability to generate proinflammatory immune responses and increase susceptibility to infection. IL-17A production is not dependent upon immune maturation or advancing gestational age.67 IL-17A is produced by T helper 17 (Th17) cells. Developmental deficiencies in Th17 arm are associated with an increased risk of systemic infection in premature neonates.67 Induction of Th17 cells from naïve helper T lymphocytes is triggered by IL-1β, IL-6, IL-21, and IL-23 in coordination with transforming growth factor (TGF)-β and RAR-related orphan receptor-γ. Low levels of TGF-β promote Th17 lymphocyte differentiation, whereas high levels stimulate the transcription factor forkhead box P3 (FOXP3) to generate regulatory T cells (Tregs). Treg cells are important in suppressing immune activity and maintenance of maternal-fetal tolerance.68 Because of their opposing immune responses, the Th17/Treg balance is vital for maintaining fetal immune homeostasis. Chorioamnionitis enhances Th17-like responses in preterm infants,69 and reduces the functionality of Tregs.70 However, further studies are needed to elucidate the role of IL-17A and TH17/Treg balance in chorioamnionitis.

Lastly, IL-1β is another important cytokine implicated in the pathogenesis of chorioamnionitis-mediated preterm birth in mice,71 rhesus monkeys,72 and humans.73 There have been several studies that have correlated the increase in IL-1β with preterm birth in humans as well as several animal species,25 and also with spontaneous delivery at term in humans.74 It is thought that IL-1β overproduction heralds labor, regardless of the presence of infection.75 Moreover, elevated IL-1β blood concentration in human neonates has been associated with preterm birth.76 IL-1β concentration and bioactivity increases in the amniotic fluid of women with preterm labor and infection, and elevated maternal plasma IL-1β are associated with preterm labor.77 IL-1 signaling mediates the initiation, amplification of inflammation, and regulation of survival and activity of neutrophils at the maternal-fetal interface during chorioamnionitis via the IRAK1 pathway.73 IRAK1, a downstream mediator in the Toll-like receptor (TLR) and IL-1R signaling pathways, has been recently identified as the critical mediator of inflammation-induced preterm birth.78 As such, IL-1β or IRAK1 may be a potential therapeutic target for chorioamnionitis and its associated morbidities.73,78

Extensive studies have been conducted to determine whether any of these inflammatory markers have diagnostic and prognostic value in cases of suspected intra-amniotic inflammation/infection. Meta-analyses have shown there is insufficient evidence to support the use of any inflammatory markers including IL-6 in maternal blood for diagnosis of chorioamnionitis in preterm premature rupture of membranes.79

Adverse outcomes:

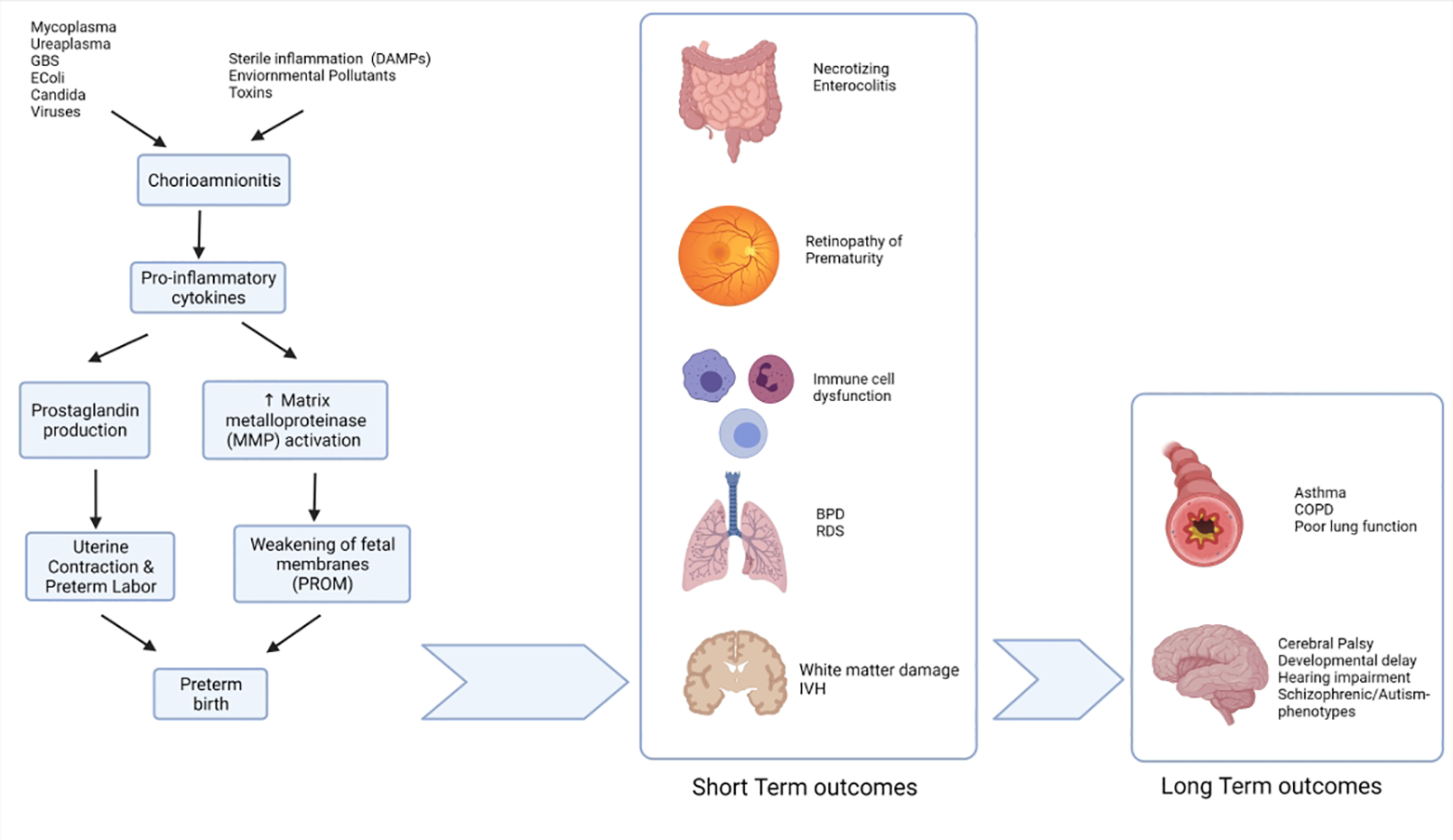

Chorioamnionitis is associated with an approximately 2 to 3.5-fold increased odds of neonatal adverse outcomes.80 These adverse outcomes include perinatal death, early-onset neonatal sepsis, septic shock, pneumonia, meningitis, intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH), cerebral white matter damage, and long-term disability including cerebral palsy, retinopathy of prematurity, necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) as well as morbidity related to preterm birth,81–86 (Fig 1). These outcomes are discussed in detail below:

-

Sepsis

Neonatal complications of include congenital sepsis, and infections such as pneumonia, dermatitis, and otitis media.21,87–90 In a recent meta-analysis, histological chorioamnionitis was associated with confirmed and any early-onset neonatal sepsis (unadjusted pooled ORs 4.42 [95% CI 2.68–7.29] and 5.88 [95% CI 3.68–9.41], respectively). Clinical chorioamnionitis was also associated with confirmed and any early-onset neonatal sepsis (unadjusted pooled ORs 6.82 [95% CI 4.93–9.45] and 3.90 [95% CI 2.74–5.55], respectively). Additionally, histologic and clinical chorioamnionitis were each associated with higher odds of late-onset sepsis in preterm neonates.81

In a large study multicenter, prospective surveillance for early-onset neonatal infections which included about 400,000 live births, 389 infants were diagnosed with early-onset sepsis, of whom 232 (60%) were exposed to clinical chorioamnionitis. 96% of preterm and 72% of term infants were not well-appearing. In contrast, only 29 cases (0.007%) of culture-positive infants were asymptomatic.91 Thus, few of the infants exposed to chorioamnionitis are infected and the infected preterm infants are generally symptomatic. Implementation of current clinical guidelines likely leads to exposure of large numbers of uninfected asymptomatic infants to antibiotics.

-

Respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) and bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD):

In chorioamnionitis, fetal breathing leads to mixing of fetal lung fluid with amniotic fluid resulting in potential lung exposure. Initial studies showed that ventilated preterm infants exposed to histologic chorioamnionitis had less RDS, but more BPD than infants not exposed to chorioamnionitis.92 Preterm infants exposed to histologic chorioamnionitis had decreased incidence of RDS, but histologic chorioamnionitis with isolation of Ureaplasma or Mycoplasma from cord blood did not correlate with a decreased risk of RDS.27 Prenatal exposure to high levels of TNFα in amniotic fluid as seen in chorioamnionitis predict RDS and prolonged postnatal ventilation, suggesting early and persistent lung injury from chorioamnionitis.93 On the contrary, Lahra et al. noticed a decreased RDS and BPD in those exposed to histological chorioamnionitis.94 Another large study in infants <28 weeks of gestation found no association between histologic chorioamnionitis, funisitis, or specific organisms and the initial oxygen requirements of the infants.95 Chorioamnionitis can alter the response to clinical outcomes. In a study of preterm infants with RDS, exposure to severe chorioamnionitis led to a poor response to surfactant, 96 possibly by altering lung surfactant lipid profiles.97

A meta-analysis of 244,000 infants concluded that chorioamnionitis increased the risk of BPD.84 However, reports from the Canadian Neonatal Network and by Laughon et al found no association of BPD with chorioamnionitis.87,95 It is possible that chorioamnionitis modulates the risk of having BPD by providing the first hit and the subsequent postnatal mechanical ventilation and oxygen exposure providing the second hit to develop BPD.98 Studies show that overall BPD risk was decreased in ventilated infants with chorioamnionitis, but increased in infants ventilated for more than 7 days or with postnatal sepsis.99 In another study, BPD was increased three-fold in infants positive for Ureaplasma or Mycoplasma.27 Thus, lung exposures to chorioamnionitis may result in variable effects on lung maturation, ranging from increased surfactant synthesis to lung injury from inflammation, depending on the organism and the duration of exposure. Lung inflammation caused by chorioamnionitis may promote progression toward BPD by interfering with multiple signaling pathways involved in lung development.98

In summary, BPD is a complex lung development/injury/repair syndrome with multiple postnatal factors contributing to its occurrence and progression. Chorioamnionitis may result in early respiratory advantage to preterm infants, but this advantage may be offset by increased risk of BPD. Some chorioamnionitis exposures may protect the infant from BPD by decreasing the severity of RDS (lung maturation) while other types of exposures may promote BPD by initiating a progressive inflammatory response.

-

Neurodevelopment

Multiple epidemiological studies have linked perinatal brain injury such as cerebral palsy, periventricular leukomalacia, and IVH with chorioamnionitis.100,101 Chorioamnionitis is associated with an increased incidence of speech delay and hearing loss at 18 months of corrected age in infants born very preterm.102 Chorioamnionitis has also been linked to various schizophrenia and autism-specific phenotypes.103

The association between clinical and/or histological chorioamnionitis and poor neurodevelopmental outcomes or death in newborns has been debated, with multiple positive and negative studies in the literature.85,86,104,105 This is likely due to varying definitions of chorioamnionitis and inappropriate adjustment for clinical factors that lie on the causal chain (eg. gestational age).106 In addition, animal models have consistently shown increased brain damage specifically in the white matter of the brain with chorioamnionitis.107,108

Inflammatory cytokines released during chorioamnionitis have been suggested as a possible cause of cerebral injury observed in human studies.109–111 These ranges from the direct effect on the cerebral vasculature causing cerebral hypoperfusion and ischemia to activation of microglia causing a direct toxic effect on oligodendrocytes and myelin via microglial production of proinflammatory cytokines, neuronal loss, and impaired neuronal guidance.112–114

-

Microbiome changes

In infants with chorioamnionitis and funisitis, stool samples collected on postnatal day 7 had a relative abundance of order Fusobacteria, genus Sneathia or family Mycoplasmataceae. Presence of these specific clades in fecal samples was associated with the higher risk of sepsis or death suggesting that specific alterations in the infant gastrointestinal microbiota induced by chorioamnionitis predispose to neonatal sepsis or death.115 In another study, Enterobacteriaceae relative abundance was higher in stool samples of infants exposed to choriomamnionits.70

-

Necrotizing enterocolits (NEC)

Meta-analyses have shown that clinical chorioamnionitis is significantly associated with NEC (12 studies; n = 22601; OR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.01–1.52; P = .04). In addition, histological chorioamnionitis with fetal involvement was highly associated with NEC (3 studies; n = 1640; OR, 3.29; 95% CI, 1.87–5.78; P ≤ .0001).116 Intrauterine exposure to inflammatory stimuli may switch innate immunity cells such as macrophages to a reactive phenotype (“priming”). Confronted with renewed inflammatory stimuli during labor or postnatally, such sensitized cells may exaggerate production of proinflammatory cytokines associated with NEC (two-hit hypothesis).117

-

Long-term programming – Barker Hypothesis

Barker et al. coined the fetal origins of adult disease hypothesis that later became known as the developmental origin of adult disease hypothesis. The unique characteristics of the fetal origin are (1) delayed onset of the insult phenotype much later, (2) the adverse effect from fetal exposure can last a lifetime for the affected individual, and (3) there is often a genetic reprogramming resulting from the prenatal exposure.118

Epigenetics describes how the environment interacts with the genome to produce heritable changes resulting in phenotypic variation without altering the DNA of the genome. Epigenetic processes include DNA methylation and demethylation and various post-translational processes. Studies have reported an association between DNA methylation changes of the imprinted gene PLAGL1 (pleomorphic adenoma gene-like 1 - associated with abnormal development and cancer) and chorioamnionitis.119 Other studies have found chorio mediated tissue-specific epigenetic modifications to the genes involved in Toll-like-receptor (TLR) signaling pathway.120 These deleterious effects in epigenetic programming may converge to induce inflammation, impair the immune system, and cause pathologic conditions lasting well into adulthood.

In a large retrospective study of 500,000 preterm infants, chorioamnionitis increased the risk of childhood asthma.121 Infants exposed to severe chorioamnionitis had increased cord blood IL-6 and greater pulmonary morbidity at age 6 to 12 months.122 Studies in preterm infants with chorioamnionitis has found higher IL-33 in maternal serum as well as in placental membranes.123,124 Unregulated IL-33 activity leads to activation of Th2 cells, mast cells, dendritic cells, eosinophils, and basophils, ultimately leading to increased expression of cytokines and chemokines that defines asthma disease.125 It is possible that this increased risk of asthma is due to altered Th2 immune cell development following in utero inflammation. Thus, chorioamnionitis can potentially influence the development and maturation of the neonatal immune system. This in utero exposure to chorioamnionitis may “prime” the developing immune system, even in the absence of infection. Such a “priming” results in a more activated and mature immunophenotype, potentially increasing the susceptibility of infants to later childhood diseases, altering their response to vaccination, or contributing to the development of immunopathological disorders.126

Fig 1:

Exposure to various microbes or sterile inflammation causing chorioamnionitis and release of various proinflammatory cytokines, which in turn causes preterm labor and/or premature rupture of membranes (PROM). These in turn lead to various short-term and long-term chorio mediated outcomes.

DAMP- damage-associated molecular patterns, BPD – Bronchopulmonary dysplasia, RDS – Respiratory distress. IVH – Intraventricular hemorrhage. COPD – Chronic Obstructive pulmonary disease.

Management

Because of the various adverse effects of chorioamnionitis as discussed above, the mere entry of chorioamnionitis in the patient’s record triggers a series of investigations and management decisions in the mother and the infant, irrespective of probable cause or clinical findings. To address these wide-ranging issues, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and American Academy of Pediatrics assembled a group of maternal and neonatal experts to formulate expert opinion on the management of chorioamnionitis.20

The term chorioamnionitis is commonly used to denote clinical suspicion of intra-uterine inflammation or infection even before any pathologic or laboratory evidence of infection or inflammation is uncovered. The findings of these tests are often not conclusive, and almost always not available until after the infant is delivered. In addition, the findings are also not always aligned with clinical signs. The term chorioamnionitis does not consistently convey the degree and severity of maternal or fetal illness leading to a clinical conundrum on how to appropriately treat the mother and infant. In addition, overexposure of newborns to broad-spectrum antibiotics pending exclusion of early-onset neonatal sepsis, or for “presumed” early-onset neonatal sepsis in the absence of a definitive diagnosis, has potential short- and long-term adverse effects such as higher risks of neonatal morbidity and mortality.127

Neonatal management of those born to chorioamnionitis

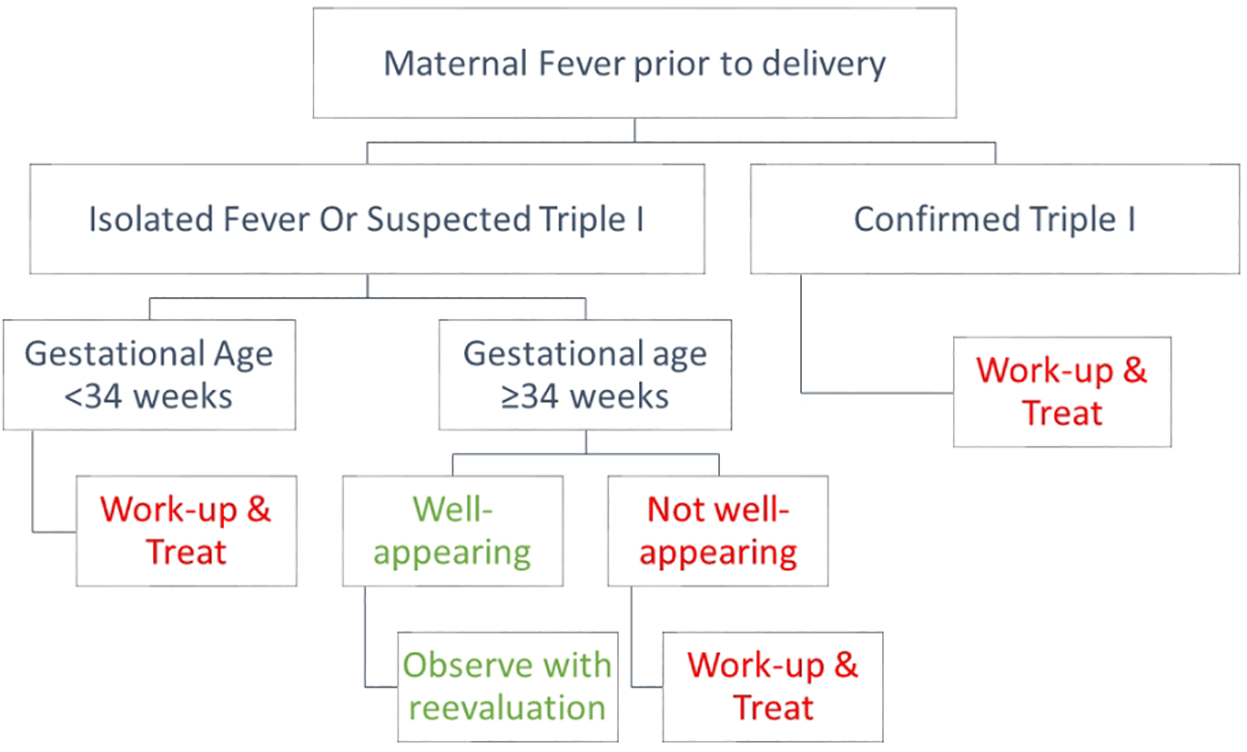

Neonatal management should be guided by the clinical category of isolated fever, suspected Triple I or confirmed Triple I, gestational age at birth, and clinical condition of the neonate (Fig 2).20

Fig 2:

Management algorithm of neonates exposed to chorioamnionitis.

(Suspected Triple I” is defined as fever with one or more of the following symptoms: leukocytosis, fetal tachycardia, or purulent cervical discharge. Confirmed Triple I should be accompanied by evidence of amniotic fluid infection).

Adapted from Higgins et. al (20)

Term and late preterm neonates:

Isolated maternal fever: Treatment is not beneficial for well-appearing term and late preterm neonates regardless of mother receiving antibiotics

Suspected Triple I: Clinical condition should guide care. The majority of well-appearing term and late preterm neonates who are asymptomatic can be closely observed without antibiotics. Using the sepsis calculator may help with the decision to treat or not to treat in such cases.128 The sepsis calculator has been able to decrease the use of antibiotics from 99.7% to 2.5% in babies exposed to chorioamnionitis.129 However, recent meta-analyses have shown that the probability of missing early-onset sepsis is higher in babies exposed to chorioamnionitis.130

Confirmed Triple I: Neonates should be treated according to current guidelines

Neonates born at <34 0/7 weeks of gestation

Isolated maternal fever: well-appearing preterm neonates can be observed if laboratory data is not favoring sepsis, but this recommendation is not evidence-based

Suspected or confirmed Triple I: neonates should be started on antibiotics as soon as cultures are obtained.

Duration of antibiotic therapy

There is a paucity of studies to guide clinical practice for the duration of antibiotics when cultures are negative. In most well-appearing infants, there is no compelling evidence that antibiotics need to be continued beyond 36–48 hours, especially when blood cultures are negative and regardless of how “abnormal” laboratory data are found in these newborns.20

Future studies

The gold standard used for the diagnosis of intra-amniotic infection/inflammation is amniotic fluid obtained by amniocentesis, which is not feasible in every case. Rapid point-of-care or near-patient testing to assess amniotic fluid for inflammatory markers may help identify patients with true intra-amniotic inflammation.131,132

In summary, chorioamnionitis exposure is common and is associated with many short-term and long-term morbidity. A better understanding of microbiome alterations and inflammatory dysregulation may help develop better treatment strategies for infants born to mothers with chorioamnionitis. To optimize outcomes, it is essential to define the consequences of chorioamnionitis in preterm infants and the underlying mechanisms by basic science and translational investigation followed by clinical research focused on important outcomes both in the NICU and in early childhood.

Funding:

The Lung Health Center Pilot Grant, The University of Alabama at Birmingham (VJ and KW)

The Kaul Pediatric Research Award, Children’s of Alabama (VJ and KW)

The NIH, NHLBI: K08 HL151907 (KW)

References:

- 1.Hamilton BE; Martin JA; Osterman MJK; Hyattsville M. Births: Preliminary Data for 2015. National Vital Statistics Reports. National Center for Health Statistics 65 (2016). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF, Iams JD & Romero R Epidemiology and Causes of Preterm Birth. Lancet 371, 75–84 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DiGiulio DB et al. Microbial Prevalence, Diversity and Abundance in Amniotic Fluid During Preterm Labor: A Molecular and Culture-Based Investigation. PLoS One 3, e3056 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldenberg RL, Hauth JC & Andrews WW Intrauterine Infection and Preterm Delivery. The New England journal of medicine 342, 1500–1507 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yoon BH et al. The Clinical Significance of Detecting Ureaplasma Urealyticum by the Polymerase Chain Reaction in the Amniotic Fluid of Patients with Preterm Labor. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 189, 919–924 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Higgins RD et al. Evaluation and Management of Women and Newborns with a Maternal Diagnosis of Chorioamnionitis: Summary of a Workshop. Obstet Gynecol 127, 426–436 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gomez R et al. The Fetal Inflammatory Response Syndrome. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 179, 194–202 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Romero R et al. Prevalence and Clinical Significance of Sterile Intra-Amniotic Inflammation in Patients with Preterm Labor and Intact Membranes. American journal of reproductive immunology : AJRI : official journal of the American Society for the Immunology of Reproduction and the International Coordination Committee for Immunology of Reproduction 72, 458–474 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nadeau-Vallee M et al. Sterile Inflammation and Pregnancy Complications: A Review. Reproduction 152, R277–R292 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bove H et al. Ambient Black Carbon Particles Reach the Fetal Side of Human Placenta. Nat Commun 10, 3866 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Familari M et al. Exposure of Trophoblast Cells to Fine Particulate Matter Air Pollution Leads to Growth Inhibition, Inflammation and Er Stress. PloS one 14, e0218799 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Menon R et al. Cigarette Smoke Induces Oxidative Stress and Apoptosis in Normal Term Fetal Membranes. Placenta 32, 317–322 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Romero R et al. A Novel Molecular Microbiologic Technique for the Rapid Diagnosis of Microbial Invasion of the Amniotic Cavity and Intra-Amniotic Infection in Preterm Labor with Intact Membranes. American journal of reproductive immunology : AJRI : official journal of the American Society for the Immunology of Reproduction and the International Coordination Committee for Immunology of Reproduction 71, 330–358 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Romero R et al. Sterile and Microbial-Associated Intra-Amniotic Inflammation in Preterm Prelabor Rupture of Membranes. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 28, 1394–1409 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Romero R et al. Sterile Intra-Amniotic Inflammation in Asymptomatic Patients with a Sonographic Short Cervix: Prevalence and Clinical Significance. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 28, 1343–1359 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kallapur SG, Presicce P, Rueda CM, Jobe AH & Chougnet CA Fetal Immune Response to Chorioamnionitis. Semin Reprod Med 32, 56–67 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olin A et al. Stereotypic Immune System Development in Newborn Children. Cell 174, 1277–1292 e1214 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roberts DJ et al. Acute Histologic Chorioamnionitis at Term: Nearly Always Noninfectious. PloS one 7, e31819 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oh KJ et al. Twenty-Four Percent of Patients with Clinical Chorioamnionitis in Preterm Gestations Have No Evidence of Either Culture-Proven Intraamniotic Infection or Intraamniotic Inflammation. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 216, 604 e601–604 e611 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higgins RD et al. Evaluation and Management of Women and Newborns with a Maternal Diagnosis of Chorioamnionitis: Summary of a Workshop. Obstet Gynecol 127, 426–436 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sung JH, Choi SJ, Oh SY, Roh CR & Kim JH Revisiting the Diagnostic Criteria of Clinical Chorioamnionitis in Preterm Birth. BJOG : an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology 124, 775–783 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Redline RW et al. Amniotic Infection Syndrome: Nosology and Reproducibility of Placental Reaction Patterns. Pediatr Dev Pathol 6, 435–448 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pacora P et al. Funisitis and Chorionic Vasculitis: The Histological Counterpart of the Fetal Inflammatory Response Syndrome. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 11, 18–25 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gomez-Lopez N et al. Are Amniotic Fluid Neutrophils in Women with Intraamniotic Infection and/or Inflammation of Fetal or Maternal Origin? American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 217, 693 e691–693 e616 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim CJ et al. Acute Chorioamnionitis and Funisitis: Definition, Pathologic Features, and Clinical Significance. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 213, S29–52 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Doyle RM et al. Term and Preterm Labour Are Associated with Distinct Microbial Community Structures in Placental Membranes Which Are Independent of Mode of Delivery. Placenta 35, 1099–1101 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goldenberg RL et al. The Alabama Preterm Birth Study: Umbilical Cord Blood Ureaplasma Urealyticum and Mycoplasma Hominis Cultures in Very Preterm Newborn Infants. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 198, 43 e41–45 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Randis TM et al. Group B Streptococcus Beta-Hemolysin/Cytolysin Breaches Maternal-Fetal Barriers to Cause Preterm Birth and Intrauterine Fetal Demise in Vivo. The Journal of infectious diseases 210, 265–273 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shurin PA, Alpert S, Bernard Rosner BA, Driscoll SG & Lee YH Chorioamnionitis and Colonization of the Newborn Infant with Genital Mycoplasmas. The New England journal of medicine 293, 5–8 (1975). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prince AL et al. The Placental Membrane Microbiome Is Altered among Subjects with Spontaneous Preterm Birth with and without Chorioamnionitis. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 214, 627 e621–627 e616 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Urushiyama D et al. Microbiome Profile of the Amniotic Fluid as a Predictive Biomarker of Perinatal Outcome. Sci Rep 7, 12171 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Combs CA et al. Amniotic Fluid Infection, Inflammation, and Colonization in Preterm Labor with Intact Membranes. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 210, 125 e121–125 e115 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maki Y, Fujisaki M, Sato Y & Sameshima H Candida Chorioamnionitis Leads to Preterm Birth and Adverse Fetal-Neonatal Outcome. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol 2017, 9060138 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.DiGiulio DB Diversity of Microbes in Amniotic Fluid. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 17, 2–11 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Romero R et al. Detection of a Microbial Biofilm in Intraamniotic Infection. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 198, 135 e131–135 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aagaard K et al. A Metagenomic Approach to Characterization of the Vaginal Microbiome Signature in Pregnancy. PloS one 7, e36466 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aagaard K et al. The Placenta Harbors a Unique Microbiome. Sci Transl Med 6, 237ra265 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mishra A et al. Microbial Exposure During Early Human Development Primes Fetal Immune Cells. Cell (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Prince AL The Placental Membrane Microbiome Is Altered among Subjects with Spontaneous Preterm Birth with and without Chorioamnionitis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 214 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.DiGiulio DB et al. Temporal and Spatial Variation of the Human Microbiota During Pregnancy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 112, 11060–11065 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Uchida K et al. Effects of Ureaplasma Parvum Lipoprotein Multiple-Banded Antigen on Pregnancy Outcome in Mice. Journal of reproductive immunology 100, 118–127 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fardini Y, Chung P, Dumm R, Joshi N & Han YW Transmission of Diverse Oral Bacteria to Murine Placenta: Evidence for the Oral Microbiome as a Potential Source of Intrauterine Infection. Infection and immunity 78, 1789–1796 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mysorekar IU & Diamond MS Modeling Zika Virus Infection in Pregnancy. The New England journal of medicine 375, 481–484 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arora N, Sadovsky Y, Dermody TS & Coyne CB Microbial Vertical Transmission During Human Pregnancy. Cell Host Microbe 21, 561–567 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sharma L & Shukla G Placental Malaria: A New Insight into the Pathophysiology. Front Med (Lausanne) 4, 117 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Qureshi F et al. Candida Funisitis: A Clinicopathologic Study of 32 Cases. Pediatr Dev Pathol 1, 118–124 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cappelletti M, Presicce P & Kallapur SG Immunobiology of Acute Chorioamnionitis. Front Immunol 11, 649 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Galask RP, Varner MW, Petzold CR & Wilbur SL Bacterial Attachment to the Chorioamniotic Membranes. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 148, 915–928 (1984). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Coultrip LL et al. The Value of Amniotic Fluid Interleukin-6 Determination in Patients with Preterm Labor and Intact Membranes in the Detection of Microbial Invasion of the Amniotic Cavity. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 171, 901–911 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Romero R, Dey SK & Fisher SJ Preterm Labor: One Syndrome, Many Causes. Science 345, 760–765 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chatterjee J, Gullam J, Vatish M & Thornton S The Management of Preterm Labour. Archives of disease in childhood Fetal and neonatal edition 92, F88–93 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lawn JE et al. Born Too Soon: Accelerating Actions for Prevention and Care of 15 Million Newborns Born Too Soon. Reprod Health 10 Suppl 1, S6 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Winer N et al. 17 Alpha-Hydroxyprogesterone Caproate Does Not Prolong Pregnancy or Reduce the Rate of Preterm Birth in Women at High Risk for Preterm Delivery and a Short Cervix: A Randomized Controlled Trial. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 212, 485 e481–485 e410 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Subramaniam A, Abramovici A, Andrews WW & Tita AT Antimicrobials for Preterm Birth Prevention: An Overview. Infectious diseases in obstetrics and gynecology 2012, 157159 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.van den Broek NR et al. The Apple Study: A Randomized, Community-Based, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Azithromycin for the Prevention of Preterm Birth, with Meta-Analysis. PLoS medicine 6, e1000191 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gravett MG et al. Immunomodulators Plus Antibiotics Delay Preterm Delivery after Experimental Intraamniotic Infection in a Nonhuman Primate Model. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 197, 518 e511–518 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Weitkamp JH et al. Histological Chorioamnionitis Shapes the Neonatal Transcriptomic Immune Response. Early human development 98, 1–6 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Spinillo A, Iacobone AD, Calvino IG, Alberi I & Gardella B The Role of the Placenta in Feto-Neonatal Infections. Early human development 90 Suppl 1, S7–9 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Romero R & Mazor M Infection and Preterm Labor. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology 31, 553–584 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Romero R et al. Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns (Damps) in Preterm Labor with Intact Membranes and Preterm Prom: A Study of the Alarmin Hmgb1. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 24, 1444–1455 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chen GY & Nunez G Sterile Inflammation: Sensing and Reacting to Damage. Nat Rev Immunol 10, 826–837 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Madsen-Bouterse SA et al. The Transcriptome of the Fetal Inflammatory Response Syndrome. American journal of reproductive immunology : AJRI : official journal of the American Society for the Immunology of Reproduction and the International Coordination Committee for Immunology of Reproduction 63, 73–92 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cua DJ & Tato CM Innate Il-17-Producing Cells: The Sentinels of the Immune System. Nat Rev Immunol 10, 479–489 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lawrence SM & Wynn JL Chorioamnionitis, Il-17a, and Fetal Origins of Neurologic Disease. American journal of reproductive immunology : AJRI : official journal of the American Society for the Immunology of Reproduction and the International Coordination Committee for Immunology of Reproduction 79, e12803 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Caron JE et al. Severely Depressed Interleukin-17 Production by Human Neonatal Mononuclear Cells. Pediatric research 76, 522–527 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Huang W, Na L, Fidel PL & Schwarzenberger P Requirement of Interleukin-17a for Systemic Anti-Candida Albicans Host Defense in Mice. The Journal of infectious diseases 190, 624–631 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schelonka RL et al. T Cell Cytokines and the Risk of Blood Stream Infection in Extremely Low Birth Weight Infants. Cytokine 53, 249–255 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Samstein RM, Josefowicz SZ, Arvey A, Treuting PM & Rudensky AY Extrathymic Generation of Regulatory T Cells in Placental Mammals Mitigates Maternal-Fetal Conflict. Cell 150, 29–38 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jackson CM et al. Pro-Inflammatory Immune Responses in Leukocytes of Premature Infants Exposed to Maternal Chorioamnionitis or Funisitis. Pediatric research 81, 384–390 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kamdar S et al. Perinatal Inflammation Influences but Does Not Arrest Rapid Immune Development in Preterm Babies. Nat Commun 11, 1284 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hirsch E, Filipovich Y & Mahendroo M Signaling Via the Type I Il-1 and Tnf Receptors Is Necessary for Bacterially Induced Preterm Labor in a Murine Model. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 194, 1334–1340 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sadowsky DW, Adams KM, Gravett MG, Witkin SS & Novy MJ Preterm Labor Is Induced by Intraamniotic Infusions of Interleukin-1beta and Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha but Not by Interleukin-6 or Interleukin-8 in a Nonhuman Primate Model. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 195, 1578–1589 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Presicce P et al. Il-1 Signaling Mediates Intrauterine Inflammation and Chorio-Decidua Neutrophil Recruitment and Activation. JCI Insight 3 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Romero R et al. Amniotic Fluid Interleukin-1 in Spontaneous Labor at Term. The Journal of reproductive medicine 35, 235–238 (1990). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nadeau-Vallee M et al. A Critical Role of Interleukin-1 in Preterm Labor. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 28, 37–51 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Skogstrand K et al. Association of Preterm Birth with Sustained Postnatal Inflammatory Response. Obstet Gynecol 111, 1118–1128 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Vitoratos N, Mastorakos G, Kountouris A, Papadias K & Creatsas G Positive Association of Serum Interleukin-1beta and Crh Levels in Women with Pre-Term Labor. Journal of endocrinological investigation 30, 35–40 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jain VG et al. Irak1 Is a Critical Mediator of Inflammation-Induced Preterm Birth. J Immunol 204, 2651–2660 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Etyang AK, Omuse G, Mukaindo AM & Temmerman M Maternal Inflammatory Markers for Chorioamnionitis in Preterm Prelabour Rupture of Membranes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Diagnostic Test Accuracy Studies. Syst Rev 9, 141 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Venkatesh KK et al. Association of Chorioamnionitis and Its Duration with Neonatal Morbidity and Mortality. J Perinatol 39, 673–682 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Beck C et al. Chorioamnionitis and Risk for Maternal and Neonatal Sepsis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Obstet Gynecol (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Villamor-Martinez E et al. Chorioamnionitis Is a Risk Factor for Intraventricular Hemorrhage in Preterm Infants: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Physiol 9, 1253 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Villamor-Martinez E et al. Chorioamnionitis as a Risk Factor for Retinopathy of Prematurity: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PloS one 13, e0205838 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Villamor-Martinez E et al. Association of Chorioamnionitis with Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia among Preterm Infants: A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Metaregression. JAMA Netw Open 2, e1914611 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Xing L et al. Is Chorioamnionitis Associated with Neurodevelopmental Outcomes in Preterm Infants? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Following Prisma. Medicine (Baltimore) 98, e18229 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Salas AA et al. Histological Characteristics of the Fetal Inflammatory Response Associated with Neurodevelopmental Impairment and Death in Extremely Preterm Infants. The Journal of pediatrics 163, 652–657 e651–652 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Soraisham AS et al. A Multicenter Study on the Clinical Outcome of Chorioamnionitis in Preterm Infants. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 200, 372 e371–376 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.De Felice C et al. Recurrent Otitis Media with Effusion in Preterm Infants with Histologic Chorioamnionitis--a 3 Years Follow-up Study. Early human development 84, 667–671 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kim YM et al. Dermatitis as a Component of the Fetal Inflammatory Response Syndrome Is Associated with Activation of Toll-Like Receptors in Epidermal Keratinocytes. Histopathology 49, 506–514 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Newton ER Chorioamnionitis and Intraamniotic Infection. Clin Obstet Gynecol 36, 795–808 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wortham JM et al. Chorioamnionitis and Culture-Confirmed, Early-Onset Neonatal Infections. Pediatrics 137 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Watterberg KL, Demers LM, Scott SM & Murphy S Chorioamnionitis and Early Lung Inflammation in Infants in Whom Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia Develops. Pediatrics 97, 210–215 (1996). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hitti J et al. Amniotic Fluid Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha and the Risk of Respiratory Distress Syndrome among Preterm Infants. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 177, 50–56 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lahra MM, Beeby PJ & Jeffery HE Maternal Versus Fetal Inflammation and Respiratory Distress Syndrome: A 10-Year Hospital Cohort Study. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 94, F13–16 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Laughon M et al. Patterns of Respiratory Disease During the First 2 Postnatal Weeks in Extremely Premature Infants. Pediatrics 123, 1124–1131 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Been JV et al. Chorioamnionitis Alters the Response to Surfactant in Preterm Infants. The Journal of pediatrics 156, 10–15 e11 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Giambelluca S et al. Chorioamnionitis Alters Lung Surfactant Lipidome in Newborns with Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Pediatric research (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Jobe AH Effects of Chorioamnionitis on the Fetal Lung. Clin Perinatol 39, 441–457 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Laughon MM et al. Prediction of Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia by Postnatal Age in Extremely Premature Infants. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 183, 1715–1722 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Wu YW & Colford JM Jr. Chorioamnionitis as a Risk Factor for Cerebral Palsy: A Meta-Analysis. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association 284, 1417–1424 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Pappas A et al. Chorioamnionitis and Early Childhood Outcomes among Extremely Low-Gestational-Age Neonates. JAMA pediatrics 168, 137–147 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Suppiej A et al. Neurodevelopmental Outcome in Preterm Histological Chorioamnionitis. Early human development 85, 187–189 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Meyer U, Feldon J & Dammann O Schizophrenia and Autism: Both Shared and Disorder-Specific Pathogenesis Via Perinatal Inflammation? Pediatric research 69, 26R–33R (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Shi Z et al. Chorioamnionitis in the Development of Cerebral Palsy: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. Pediatrics 139 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Maisonneuve E, Ancel PY, Foix-L’Helias L, Marret S & Kayem G Impact of Clinical and/or Histological Chorioamnionitis on Neurodevelopmental Outcomes in Preterm Infants: A Literature Review. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod 46, 307–316 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Thomas W & Speer CP Chorioamnionitis: Important Risk Factor or Innocent Bystander for Neonatal Outcome? Neonatology 99, 177–187 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Schmidt AF et al. Intra-Amniotic Lps Causes Acute Neuroinflammation in Preterm Rhesus Macaques. J Neuroinflammation 13, 238 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Gisslen T, Singh G & Georgieff MK Fetal Inflammation Is Associated with Persistent Systemic and Hippocampal Inflammation and Dysregulation of Hippocampal Glutamatergic Homeostasis. Pediatric research 85, 703–710 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kaukola T et al. Population Cohort Associating Chorioamnionitis, Cord Inflammatory Cytokines and Neurologic Outcome in Very Preterm, Extremely Low Birth Weight Infants. Pediatric research 59, 478–483 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Hansen-Pupp I et al. Inflammation at Birth Is Associated with Subnormal Development in Very Preterm Infants. Pediatric research 64, 183–188 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Galinsky R, Polglase GR, Hooper SB, Black MJ & Moss TJ The Consequences of Chorioamnionitis: Preterm Birth and Effects on Development. J Pregnancy 2013, 412831 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Yanowitz TD et al. Hemodynamic Disturbances in Premature Infants Born after Chorioamnionitis: Association with Cord Blood Cytokine Concentrations. Pediatric research 51, 310–316 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Leviton A & Gressens P Neuronal Damage Accompanies Perinatal White-Matter Damage. Trends Neurosci 30, 473–478 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Khwaja O & Volpe JJ Pathogenesis of Cerebral White Matter Injury of Prematurity. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 93, F153–161 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Puri K et al. Association of Chorioamnionitis with Aberrant Neonatal Gut Colonization and Adverse Clinical Outcomes. PloS one 11, e0162734 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Been JV, Lievense S, Zimmermann LJ, Kramer BW & Wolfs TG Chorioamnionitis as a Risk Factor for Necrotizing Enterocolitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. The Journal of pediatrics 162, 236–242 e232 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Garzoni L, Faure C & Frasch MG Fetal Cholinergic Anti-Inflammatory Pathway and Necrotizing Enterocolitis: The Brain-Gut Connection Begins in Utero. Front Integr Neurosci 7, 57 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Calkins K & Devaskar SU Fetal Origins of Adult Disease. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care 41, 158–176 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Liu Y et al. DNA Methylation at Imprint Regulatory Regions in Preterm Birth and Infection. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 208, 395 e391–397 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Lu L & Claud EC Intrauterine Inflammation, Epigenetics, and Microbiome Influences on Preterm Infant Health. Curr Pathobiol Rep 6, 15–21 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Getahun D et al. Effect of Chorioamnionitis on Early Childhood Asthma. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine 164, 187–192 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.McDowell KM et al. Pulmonary Morbidity in Infancy after Exposure to Chorioamnionitis in Late Preterm Infants. Ann Am Thorac Soc 13, 867–876 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Cekmez Y et al. Upar, Il-33, and St2 Values as a Predictor of Subclinical Chorioamnionitis in Preterm Premature Rupture of Membranes. J Interferon Cytokine Res 33, 778–782 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Topping V et al. Interleukin-33 in the Human Placenta. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 26, 327–338 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Borish L & Steinke JW Interleukin-33 in Asthma: How Big of a Role Does It Play? Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 11, 7–11 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Jackson CM et al. Pulmonary Consequences of Prenatal Inflammatory Exposures: Clinical Perspective and Review of Basic Immunological Mechanisms. Front Immunol 11, 1285 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Kuppala VS, Meinzen-Derr J, Morrow AL & Schibler KR Prolonged Initial Empirical Antibiotic Treatment Is Associated with Adverse Outcomes in Premature Infants. The Journal of pediatrics 159, 720–725 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Puopolo KM et al. Estimating the Probability of Neonatal Early-Onset Infection on the Basis of Maternal Risk Factors. Pediatrics 128, e1155–1163 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Money N, Newman J, Demissie S, Roth P & Blau J Anti-Microbial Stewardship: Antibiotic Use in Well-Appearing Term Neonates Born to Mothers with Chorioamnionitis. J Perinatol 37, 1304–1309 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Pettinger KJ, Mayers K, McKechnie L & Phillips B Sensitivity of the Kaiser Permanente Early-Onset Sepsis Calculator: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. EClinicalMedicine 19, 100227 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Musilova I et al. Vaginal Fluid Interleukin-6 Concentrations as a Point-of-Care Test Is of Value in Women with Preterm Prelabor Rupture of Membranes. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 215, 619 e611–619 e612 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Lee SM et al. A Transcervical Amniotic Fluid Collector: A New Medical Device for the Assessment of Amniotic Fluid in Patients with Ruptured Membranes. J Perinat Med 43, 381–389 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]