Abstract

Heavy metals are ubiquitously present in nature, including soil, water, and thus in plants, thereby causing a potential health risk. This study has investigated the role and efficiency of the chickpea metallothionein 1 (MT1) gene against the major toxic heavy metals, i.e., As [As(III) and As(V)], Cr(VI), and Cd toxicity. MT1 over-expressing transgenic lines had reduced As(V) and Cr(VI) accumulation, whereas Cd accumulation was enhanced in the L3 line. The physiological responses (WUE, A, Gs, E, ETR, and qP) were noted to be enhanced in transgenic plants, whereas qN was decreased. Similarly, the antioxidant molecules and enzymatic activities (GSH/GSSG, Asc/DHA, APX, GPX, and GRX) were higher in the transgenic plants. The activity of antioxidant enzymes, i.e., SOD, APX, GPX, and POD, were highest in the Cd-treated lines, whereas higher CAT activity was observed in As(V)-L1 and GRX in Cr-L3 line. The stress markers TBARS, H2O2, and electrolyte leakage were lower in transgenic lines in comparison to WT, while RWC was enhanced in the transgenic lines, and the transcript of MT1 gene was accumulated in the transgenic lines. Similarly, the level of stress-responsive amino acid cysteine was higher in transgenic plants as compared to WT plants. Among all the heavy metals, MT1 over-expressing lines showed a highly increased accumulation of Cd, whereas a non-significant effect was observed with As(III) treatment. Overall, the results demonstrate that Arabidopsis thaliana transformed with the MT1 gene mitigates heavy metal stress by regulating the defense mechanisms in plants.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12298-021-01103-1.

Keywords: Arabidopsis thaliana, Chickpea, Heavy metals, Metallothionein, Oxidative stress, Transgenics

Introduction

Heavy metals are very potent environmental pollutants, and their exposure continues to grow in every part of the world (Jaishankar et al. 2014). Heavy metals of soil and water lead to a reduction in agricultural yield and elevate food contamination (Shahid et al. 2016). Heavy metals-mediated food toxicity causes several health risks. Mainly, three types of heavy metals, such as arsenic (As), chromium (Cr), and cadmium (Cd), contaminate the water and soil, which is very toxic to human health as well as plants (Lambert et al. 2000). Among these heavy metals, As is a non-threshold and ranked first as a carcinogenic heavy metal, poses a significant threat to plant and human health (Zhao et al. 2010). Groundwater is the primary source of As contamination in humans and plants (Norton et al. 2009). The contamination of As in the food chain is of worldwide concern and is not restricted within the national boundaries. In natural conditions, As abundantly occurs in the two inorganic forms, i.e., arsenite [As(III)] and arsenate [As(V)]. As(III) is more dominant under anoxic paddy fields and is readily taken up by the plants resulting in many fold higher toxicity than As(V). As(V) mainly enters in the root cells through high-affinity phosphate (PO43−) transporters while As(III) enters mainly through aquaporin channels (Ma et al. 2008; Muehe et al. 2014). Root cells are the first tissues to be exposed to As, where it inhibits root extension and proliferation. Arsenic is translocated from root to shoot, where it severely inhibits the growth and development of plants by arresting leaf expansion, reducing biomass, loss in reproductive potential, and subsequent fruit development (Garg and Singla 2011).

Chromium is the second most frequent metal contaminant in water, soil, and sediments, posing a serious environmental concern and human hazard. It is the 7th most abundant element of the earth's crust (Katz and Salem 1994). Cr(III) and Cr(VI) are the most stable types between different valence states. Cr(VI) is highly toxic to living organisms. Chromium is present in the hexavalent compounds commonly used in industry, tanning, and wood preservation. The anthropogenic activities have led to the extensive contamination of Cr, resulting in its increased bioavailability and mobility (Kotaś and Stasicka 2000). Chromium is mainly taken up by the sulfate and iron carriers (Shanker et al. 2005). Chromium is very toxic for plants and highly deleterious to their growth and development, which ultimately affects the total dry matter production (Peralta et al. 2001).

Cadmium (Cd) is one of the most toxic heavy metals, causing severe abnormalities in plants (Prasad 1995). Cadmium mainly gets accumulated in the grains of the plant. It is readily taken up by the root cells of the plant and transported from the root to the shoot, resulting in the alteration of the biochemical and physiological processes and thereby adversely affecting the growth and development of plants (Sgherri et al. 2001). Cadmium contamination has created an increasing challenge for environmental quality and food security (Shanying et al. 2017). In plants, Cd mainly blocks the synthesis of chlorophyll and photochemical reaction centers, of which PSII is the most affected by Cd toxicity (Kato and Shimizu 1987; Chugh and Sawhney 1999). Cadmium also damages lipids and proteins by generating deleterious reactive oxygen species [ROS] (Lesser 2006).

To counter heavy metal toxicity, the plant regulates the different defense mechanisms and other small molecules such as metallothioneins (MT), glutaredoxins (GRX), and phytochelatins. MTs are ubiquitous, low molecular weight, cysteine-rich metal-chelating proteins involved in the cellular metal homeostasis and their detoxification process, but their function(s) in abiotic stress tolerance, especially against heavy metals, are broadly unexplored (Cobbett and Goldsbrough 2002). MTs are classified into two classes i.e. class I and class II, class I is reported from mammals while class II is described in plants. Plant MTs are further divided into four types i.e. type I–IV. Plants MTs are reported to work with zinc transporters to regulate the homeostasis of cellular zinc, possibly by modulating the concentration of cellular zinc ions (Kimura and Kambe 2016). Potential exposure to heavy metals can change cellular zinc homeostasis. Toxic heavy metals can disrupt the normal biochemical as well as physiological functions of the plant. Several reports indicate that the plant MTs possibly function as efficient scavengers of reactive oxygen species (ROS) production when plants are exposed to the different biotic and abiotic stresses (Chandlee and Scandallios 1984; Chatthai et al. 1997). The ROS generated during abiotic stress is generally accompanied by increased activities of many antioxidants in plants, but it may also be regulated by MTs (Sairam et al. 2002). The role of MT in scavenging ROS against metal stress has yet to be deciphered. Koh and Kim (2001) have reported that MT can scavenge ROS by activating SOD by supplying metals like Cu or Zn. A study by Guo et al. (2003) has described in detail the tissue-specific expression of the Arabidopsis MT gene. The lack of MT modulates Cu level and distribution in parts of the plants (Benatti et al. 2014). Several studies have analyzed the expression of MT in plants against Cd toxicity. However, the role of plant MTs against other primary heavy metals such as As and Cr are still poorly understood. In a transcriptomic study of chickpea, the type I MT (MT1) was upregulated during drought stress and its role in the mitigation of ROS during drought was validated in Arabidopsis thaliana in our previous study (Dubey et al. 2019). Since ROS is the central stress molecule during abiotic/biotic stress and MTs are known to scavenge ROS during stress, it prompted us to validate chickpea MT1’s role under major heavy metals stresses.

In light of these findings, the present study was intended to investigate the following questions. Does MT1 efficiently provide tolerance against As and Cr as well? Whether MT1 efficiently regulates the antioxidant mechanisms and physiological performance against As and Cr in Arabidopsis. Our findings report a protective role of MT1 and therefore offer a genetic engineering strategy to improve safer crop production in the regions contaminated with several heavy metals.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

Arabidopsis thaliana ecotype Col-0 seeds were sown in plastic cups containing soilrite potting mixture, watered with Hoagland's solution, and vernalized in the dark at 4 °C for 48 h. After 48 h, seeds were grown in a 16/8 light/dark with 200 µmol s−1 m−2 intensity of photoperiod at 22 ± 0.05 °C. The shoot tips of 8–10 cm tall plants were used for floral dip transformation with chickpea with MT1 gene by following the protocol of Clough and Bent (1998). Three transgenic lines transformed with chickpea MT1 gene (L-1, L-2, and L-3) were screened and analyzed to assess metals stress tolerance at third-generation assuming homozygous transgenic plants. Five-day-old germinated plantlets (transgenic and WT) were transferred in cups filled with inert potting mix and irrigated with Hoagland’s medium for growth. After two weeks, fully grown seedlings (fully expanded leaf stage) were treated with aqueous solutions of heavy metals for one week. The concentration of metal treatment to the transgenic and their respective WT was abbreviated as arsenite [As (III) 25 µM], arsenate [As (V) 50 µM], Cadmium [Cd 500 µM] and Chromium [Cr (VI) 250 µM].

Gene cloning, construct design, Agrobacterium-mediated transformation and selection of the putative transgenic events of Arabidopsis thaliana

The construct for over-expression of chickpea MT1 gene was designed according to methods described previously (Fig. S1) (Dubey et al. 2019; Jyothishwaran et al. 2007). The (T1) plants were selected based on their resistance to kanamycin. Further, the transformation was verified by PCR using the chickpea MT1 gene-specific primers (Fig. S2). The plants were fully grown up to T3 generation to obtain the homozygous transgenic lines in the plant growth chamber. All the functional validation was done in the T3 plants.

Preparation of RNA and transcript analysis by qRT-PCR

The MT1 gene expression was performed by qRT-PCR using the total RNA extracted from the transgenic and WT Arabidopsis plant. The cDNA was synthesized from total RNA following the manufacturer’s method in the cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Scientific, USA). The housekeeping gene of Arabidopsis actin was used as a reference to calculate the relative expression. The relative expression of the MT1 was calculated by the 2−∆∆CT method (Livak and Schmittgen 2001). The sequences of oligos used in the present study are given in Table S1.

Quantification of bio-molecules and enzymatic assays of transgenic A. thaliana under metal stress

The total content of protein was estimated spectrophotometrically following the method of Bradford (1976) at 595 nm (Spectramax 340PC, Molecular Devices, USA). The total protein content was estimated using Bradford reagent determined by standard curve of bovine serum albumin (BSA). The estimation of cysteine was done spectrophotometically at 560 nm, based on the protocol by Gaitonde (1967). Enzymatic antioxidants (SOD, GPX, APX, Catalase, POD, GRX), was determined by following our earlier publication (Beauchamp and Fridovich 1971; Dubey et al. 2019). In brief, 300 mg of the leaf was ground in a chilled mortar and pestle and extracted in 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) containing 1 mM EDTA and 1% (w/v) polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP). The homogenate was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 15 min. For estimation of ascorbic acid, the method of Kampfenkel et al. (1995), while for GSH/GSSG measurement, Anderson (1985) method was followed. The TBARS was determined spectrophotometrically at 532 nm and 600 nm following the method of Hodges et al. (1999) and the amount was calculated by deducting the turbidity at 600 nm from absorbance at 532 nm. Hydrogen peroxide levels were estimated according to Velikova et al. (2000).

Measurement of physiological performance using Li-Cor

Physiological performance was observed by subjecting the leaves to a gas exchange system (Li-Cor 6400XT; Li-Cor, Inc., USA). The rate of airflow was constant, and the VPD (vapor pressure deficit) was lower than 2 kPa. The leaf temperature (T) was 25 °C, and the CO2 concentration was 400 µmol (CO2) mol−1 air). The relative humidity (RH) was 55–60%, were constant for all plants. The photosynthetic rate (A), water use efficiency (WUE), stomatal conductance (Gs), leaf transpiration (E), photochemical quenching (qP), non-photochemical quenching (qN), and electron transport rate (ETR) were recorded in the fully open leaves.

Analysis of the metal accumulation in transgenic and WT plants of Arabidopsis

The content of metals [As (III), As (V), Cd, Cr] was measured following the method of Mallick et al. (2013). The ~ 300 mg of dried plant biomass were digested using 3HNO3: H2O2 in a microwave digester (Mars 6 240/50, CEM, USA). The digested samples were filtered through Whatman filter paper no. 42 and dissolved in the Milli-Q water containing 0.1 N HNO3 and maintained the volume up to 15 ml. The accumulation of As (III), As (V), Cr (VI), and Cd were measured using Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS, Agilent 7500 cx) using argon to light the plasma.

Determination of relative conductivity (electrolyte leakage) and relative water content (RWC)

To measure relative conductivity (electrolyte leakage), the method developed by Bandurska (2000) was followed. In short, 100 mg leaves were cut into pieces and incubated into autoclaved water at room temperature for 3 h, and then conductivity was recorded by an electrolyte conductivity meter (Eutech PC700, Thermo Fisher Scientific™). The leaves were boiled at 70 °C for 20 min and then cooled at room temperature. Again, the electric conductivity was recorded, and the following formula was used to estimate the percentage of injury Index (I):

I (%) = C1/C2 × 100, where C1 and C2 are the conductivity of samples before and after boiling, respectively.

Relative water conductivity (RWC) was measured following the (Turner 1981; Lafitte 2002) method. In brief, the fresh weight (FW) of leaves was taken, and then they were incubated in water at room temperature for 6 h to become fully turgid, and then again, the weight (TW) was measured. The fully turgid leaves were then dried completely at 70 °C, and weight was recorded. The following equation was used to calculate the RWC:

Statistical analysis

All the values are the average of three replicates. Some values are presented as a percentage increase or decrease respective to WT plants. The significant differences were shown by using Duncan's Multiple Range Test (DMRT).

Results

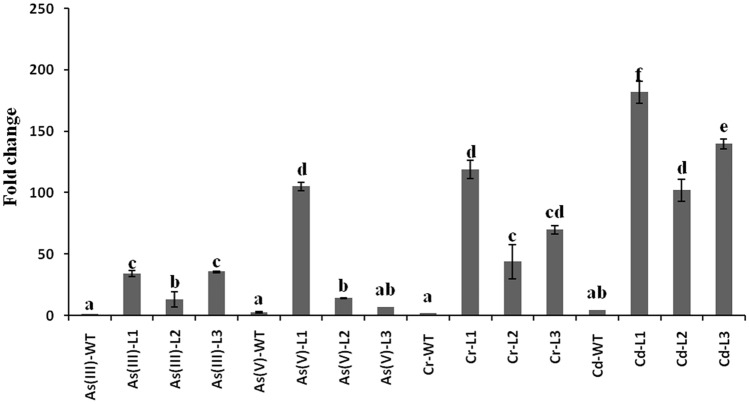

MT1 gene showed enhanced transcript level in transgenic plants against metals exposure

The transcript level of MT1 gene was enhanced in the over-expressing lines in comparison to WT plants against metals exposure. After AsIII treatment, the transcript level was found to be 40 fold higher in AsIII-L1 and AsIII-L3 transgenic lines while it was increased up to eightfold change in the L2 line compared to AsIII-WT (Fig. 1). Similarly, the transcript level was increased in all transgenic lines of As(V)-treated plants. The highest increase (105 fold change) was observed in the As(V)-L1 transgenic line. The transcript level was also significantly higher in transgenic lines of Cr exposed plants respective to its Cr-WT. It was highest (110 fold change) in the Cr-L1 line, while 40 and 60 fold change higher in Cr-L2 and Cr-L3 lines, respectively. Also, in Cd-treated plants, the transcript level was highest in the transgenic lines. The highest expression (190 fold change) was observed in the Cd-L1 line while 100 and 140 fold change in Cd-L1 and Cd-L2, respectively, compared to the Cd-WT plant. Overall, results exhibited that the Cd-L1 has highly increased the MT1 expression among all the metal exposures and lines.

Fig. 1.

The total transcript level of MT1 gene.Relative expression of MT1 gene in transgenic Arabidopsis under metal stress. The treatment abbreviation is treatment-genotype/line: Arsenite to WT (As(III)-WT); arsenate to WT (As(V)-WT), chromium to WT (Cr-WT); cadmium to WT (Cd-WT); arsenite to L1, L2,L3 (As(III)-L1, As(III)-L2, As(III)-L3); arsenate to L1, L2,L3 (As(V)-L1, As(V)-L2, As(V)-L3);chromium to L1, L2,L3 (Cr-L1, Cr-L2, Cr-L3);cadmium to L1, L2,L3 (Cd-L1, Cd-L2, Cd-L3).Significance of the mean values have been compared for each parameter separately (Duncan’s test, p < 0.05) where bars marked with same letters are not significantly different

Transgenic plants showed enhanced tolerant phenotype under metals stress

In this study, after one week of heavy metals stress treatment, the transgenic seeds showed enhanced seed germination efficiency while less germination rate was observed in WT seeds (Fig. 3S). The root lengths and biomass of the transgenic seedlings were observed to be enhanced compared to WT seedlings after six days of heavy metals stress treatment. The treatment of As(III) reduced the biomass in WT, while transgenic lines enhanced the biomass against As(III) treatment (Table 1). The transgenic line 3 (L3) showed the highest biomass (63%) as compared to the WT As(III). The root length of L1 was highest among all lines, and it was 93% higher as compared to WT (Fig. 4S). Similarly, the As(V) treatment reduced the biomass in WT while enhanced biomass in all the transgenic lines. The highest biomass (36%) and length (76%) were observed in As(V)-L2 line as compared to As(V)-WT. Likewise, Cr and Cd also reduced the biomass of WT, while increased biomass and lengths were observed in transgenic lines. The maximum biomass was observed in Cr-L2 (116%) and Cd-L2 (128%) while the lengths were also enhanced, which were 81% in Cr-L2 and 111% in Cd-L2 transgenic lines as compared to their respective WT.

Table 1.

Different levels of stress markers TBARS, H2O2, and morphological parameters (length and biomass) in wild-type and transgenic plants under different metal stresses

| Arabidopsis plants | Length (cm) | Fresh weight (mg) | TBARS (µmol g−1 FW) |

H2O2 (nmol g−1 FW) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| As(III)-WT | 3.33 ± 0.29a | 3.17 ± 0.29a | 12.26 ± 0.19d | 253.23 ± 31.78ab |

| As(III)-L1 | 6.40 ± 0.10d | 4.17 ± 0.29b | 10.31 ± 1.26c | 217.68 ± 38.67a |

| As(III)-L2 | 4.60 ± 0.17b | 4.50 ± 0.50b | 11.29 ± 1.22cd | 223.09 ± 29.39a |

| As(III)-L3 | 5.37 ± 0.32d | 5.17 ± 1.04c | 10.24 ± 0.25c | 220.75 ± 1.61a |

| As(V)-WT | 3.27 ± 0.40a | 4.77 ± 0.25a | 11.27 ± 0.26cd | 344.42 ± 22.69b |

| As(V)-L1 | 5.57 ± 0.25d | 6.00 ± 0.50c | 10.53 ± 0.46c | 226.71 ± 22.77a |

| As(V)-L2 | 5.77 ± 0.29d | 6.50 ± 0.50c | 8.56 ± 0.46a | 240.75 ± 3.23a |

| As(V)-L3 | 4.50 ± 0.50b | 5.83 ± 0.29b | 10.15 ± 1.29bc | 214.40 ± 68.34a |

| Cr(VI)-WT | 3.40 ± 0.17a | 3.17 ± 0.29a | 10.31 ± 0.22c | 608.51 ± 11.91d |

| Cr(VI)-L1 | 5.73 ± 0.12d | 5.33 ± 0.29c | 9.17 ± 0.76b | 367.18 ± 28.67b |

| Cr(VI)-L2 | 6.17 ± 0.58d | 6.87 ± 0.76cd | 9.53 ± 0.46b | 393.09 ± 24.39b |

| Cr(VI)-L3 | 5.83 ± 0.29d | 5.63 ± 1.04c | 10.06 ± 0.46b | 380.75 ± 1.61b |

| Cd-WT | 3.00 ± 0.50a | 3.67 ± 0.29a | 9.95 ± 1.09b | 444.12 ± 42.69c |

| Cd-L1 | 5.20 ± 0.50d | 6.50 ± 0.50d | 8.31 ± 0.12a | 338.71 ± 42.77b |

| Cd-L2 | 6.33 ± 0.76c | 8.40 ± 0.29d | 7.95 ± 1.09a | 340.75 ± 3.23b |

| Cd-L3 | 6.00 ± 0.40c | 8.00 ± 1.00d | 8.31 ± 0.32a | 314.40 ± 68.34b |

Significance of the mean values have been compared for each parameter separately (Duncan’s test, p < 0.05) where bars marked with different letters are significantly different

MT1 over-expression reduced the stress markers and increased the antioxidant molecules

Responses of metal exposure in WT and overexpressing lines were determined by evaluating the changes in biochemical parameters. The stress markers are substances that show toxicity inside the cells. One of the most crucial stress markers, i.e., thiobarbituric acid reactive substance (TBARS), was estimated, and an increased level was observed in all WT plants respective to their transgenic lines. In As(III) treated lines, the value of TBARS (12.26 µM g−1 FW) was highest in the WT, while it was decreased significantly in all transgenic lines, as compared to WT of Arabidopsis transformed with the MT1 gene (Table 1). The highest significant decrease (16.47% and 16%) in the TBARS level was observed in As(III)-L3 and As(III)-L1 lines. Similarly, the As(V)-WT showed a higher level of TBARS (11.27 µM g−1 FW) compared to As(V) treated all their transgenic lines. The lowest level (24%) was observed in As(V)-L2 line as compared to its respective WT control. The Cr treated transgenic lines also showed a lower level of TBARS as compared to Cr-WT. Lowest level (11%) was calculated in Cr-L1 line. however, their differences were insignificant. A similar pattern was observed in Cd-treated lines where L1–L3 shows a lower level of TBARS as compared to Cd-WT.

The level of ROS, i.e., hydrogen peroxide, was estimated and found that all respective WT treated with heavy metals exhibited a higher level of H2O2 in comparison to their transgenic lines (L1–L3) (Table 1). Most of the transgenic lines treated with As(III) showed lower content of H2O2 as compared to As(III)-WT. The least content was estimated in As(III)-L1 line, showed less toxicity (14%) of As(III) in transgenic plants as compared to As(III)-WT. Similar observations were recorded in the As(V)-treated transgenic lines, where, As(III)-L3 line showed the lowest (15%) level of H2O2 as compared to their its respective WT control. During Cr treatment, the reduction in the H2O2 level was very high and significant. Its level in WT was observed very high, while it was reduced (40%) in the Cr-L1 line of the transgenic plant. Transgenic lines treated with Cd showed a lower level of H2O2 as compared to their WT plants. The lowest level (29% less than WT) of H2O2 was observed in the Cd-L3 line in comparison to their WT.

The leakage of ions through the plasma membrane was observed as relative conductivity g−1 FW that shows the toxicity of metals in plant cells. The lower relative conductivity was observed in all transgenic lines compared to their respective WT under each heavy metal stress (Fig. S5A). The relative conductivity was lowest (31%) in As(III)-L3 in comparison to As(III)-WT. A similar leakage pattern was observed in all three lines of As(V) treated plants. The lowest (20%) leakage was observed in As(V)-L1 of the transgenic plant, as compared to its WT. The WT plants treated with Cr metal had an enhanced level of relative conductivity as compared to transgenic lines. Line L2 of Cr-treated plants showed the lowest (28%) relative conductivity as compared to WT. Likewise, WT of Cd-treated plants had a higher level of relative conductivity, while transgenic lines showed a lower level of relative conductivity; it was lowest in the Cd-L2, which is 18% lower than WT.

The relative water content in transgenic lines was higher as compared to WT. In As(III)-L1–L3, the percentage of RWC was higher in transgenic lines respective to WT. The highest increase was calculated in As(III)-L1 line (Fig. S5B). Similarly, the As(V) treated lines showed a higher percentage of RWC as compared to WT plants. The highest increase of 84.01% was observed in As(V)-L1 line, as compared to As(V)-WT (60.17%). Likewise, the RWC was highest in the Cr-L1 line (89.39%) compared to WT (61.18%). Cd treated lines also showed a higher percentage of RWC as compared to WT. The Cd-L1 showed the highest level of RWC (86.31%) compared to their WT (63.19%) plants.

Metal exposure triggers the formation of more reactive oxygen species (ROS), resulting in oxidative stress in plants. During oxidative stress, plant cells shift their reducing state to oxidizing state and thus synthesize the antioxidant molecules to reverse the state. Plants synthesize mainly two antioxidant molecules, i.e., Asc (ascorbate) and GSH (reduced glutathione), to maintain the reducing environment in the cell. Mainly two reducing equivalents are synthesized by plants for normal functioning of the cell i.e. ascorbate (Asc) and glutathione (GSH). The ratio of Asc/DHA and GSH/GSSG determines the level of oxidative stress in cells during metal exposure. A higher ratio indicates low stress while a low ratio indicates higher oxidative stress. In this work, the Asc/DHA (ascorbate/dehydroascorbate) ratio was enhanced in overexpressing lines and lower in WT. The ratio was higher in the treatments of As(III), As(V), Cr, and Cd as compared to WT plants (Table S2). This was highest (156%) in As(III)-L3 line compared to WT plants. Similarly, in the As(V)-treated lines, the As(V)-L2 line showed the highest ratio (79%) as compared to WT plants. Likewise, the ratio of Asc/DHA was increased (120%) in the Cr-L3 line of the transgenic plants. Similarly, the L1 line of Cd-treated plants showed the highest Asc/DHA ratio (171%) in comparison to WT plants. The other vital molecules of the cell responsible for maintaining the reducing environment of the cell, reduced to oxidized glutathione ratio (GSH/GSSH), were also estimated and found to be enhanced in all transgenic lines against every metal treatment. The As(III)-L1 showed an increased GSH/GSSG ratio (174%) among all As(III) treated lines as compared to As(III)-WT (Table S2). In the As(V)-treated plants, the As(III)-L1 showed the highest ratio (99%) as compared to their WT plant. Similarly, the Cr-L2 line showed the highest ratio (82%) compared to WT, while L3 of Cd-treated plants showed a maximum ratio (92%) compared to their Cd-WT.

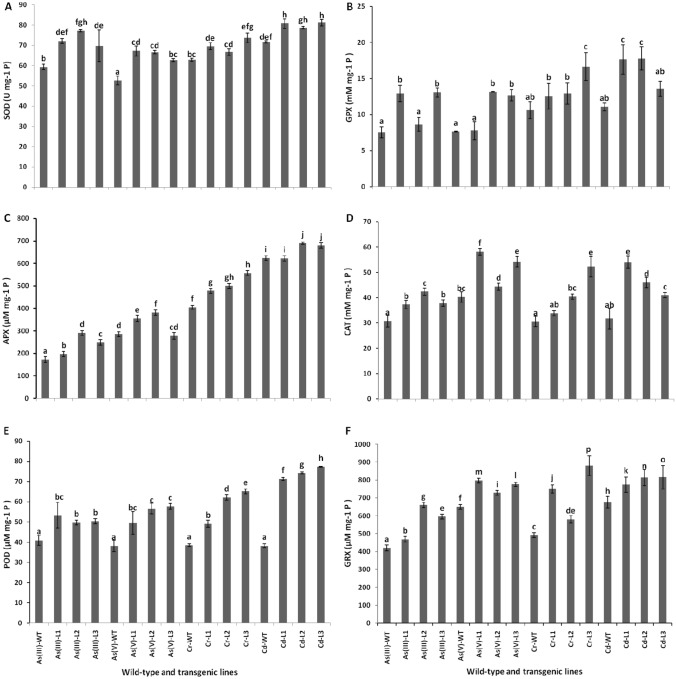

Transgenic plants showed increased antioxidant enzyme activities as compared to WT

Plants have a strong antioxidant tolerance mechanism to counter stress against biotic and abiotic factors. In this study, the activity of the antioxidant enzyme, i.e., SOD, was significantly enhanced (33 and 23%) in the As(III)-L1, L2, and L3, respectively, as compared to As(III)-WT (Fig. 2A). Similarly, compared to As(V)-WT, SOD was significantly enhanced in all three transgenic lines of the As(V)-treated plants. All the lines of Cr treated plants also exhibited increased SOD activity compared to their WT plants, except in L1. The activity of SOD was significantly higher in all lines of Cr treated plants as compared to WT. The activities of GPX were increased (71.35 and 73.20%) in L1 and L3 lines, respectively, as compared to As(III)-WT (Fig. 2B). Similarly, in As(V)-treated plants, L2 and L3 showed a significant increase in GPX activity (72.47 and 66%), as compared to their WT. Similar to the As treatments, the treatment of Cr significantly increased the activity of GPX in all the transgenic lines. The maximum significant increase of 57% was observed with the L3 as compared to its WT. Likewise, the activity of GPX was also increased in L1 (59%) and L2 (61%) against Cd treatment. Similar to the GPX activities, the APX activities were significantly increased in all lines of As(III) and As(V) treatments (Fig. 4C). The treatments of Cr and Cd also increased the APX activity in most of the lines. In Cr treated lines, the maximum activity (68%) was shown by the L1 line compared to WT control of Cr. Similarly, the Cd-treated lines also showed increased activity of APX. The maximum increase in APX activity (11%) was observed in the L2 line compared to its control. Another important antioxidant enzyme, i.e., CAT, showed higher activity in lines in comparison to their WT (Fig. 4D). Among all the lines and WT, the maximum activity of CAT was observed in As(V)-L1. Similarly, POD activity was also significantly higher in all the lines of the treatments as compared to their respective WT (Fig. 4E). The maximum POD activity was observed in all the lines of Cd-treated plants. The activity of GRX was also increased significantly in all the lines compared to their WT, which was highest in Cr-L3 (Fig. 4F). Overall, results indicated that the MT1 over-expressing lines significantly increased the antioxidant enzyme activities, where the activities of SOD, APX, GPX, and POD were highest in Cd-treated lines. However, the highest activity of CAT was observed in As(V)-L1 and GRX in Cr-L3.

Fig. 2.

Antioxidant enzyme activities in WT and transgenic Arabidopsis plants under different metal stresses. A SOD (U mg−1 P), B GPX (μM mg−1 P), C APX (μM mg−1 P), D CAT (μM mg−1 P), E POD (μM mg−1 P), F GRX (μM mg−1 P), Significance of the mean values have been compared for each parameter separately (Duncan’s test, p < 0.05) where bars marked with different letters are significantly different

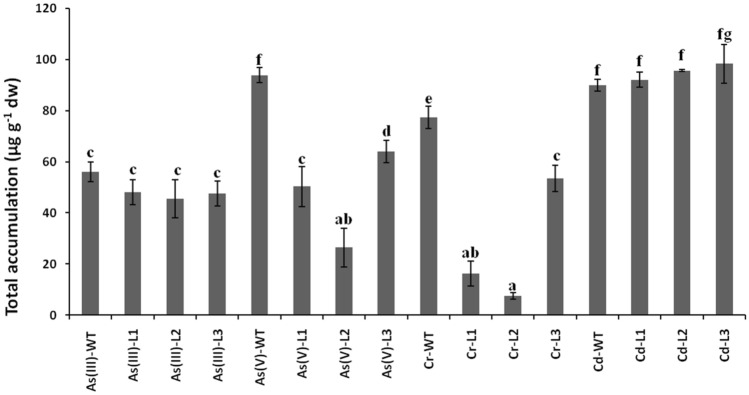

Fig. 4.

The total accumulation of heavy metals. Total accumulation of As(III), As(V), Cr(VI), and Cd in wild-type and transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana plants. Significance of the mean values have been compared for each parameter separately (Duncan’s test, p < 0.05) where bars marked with different letters are significantly different

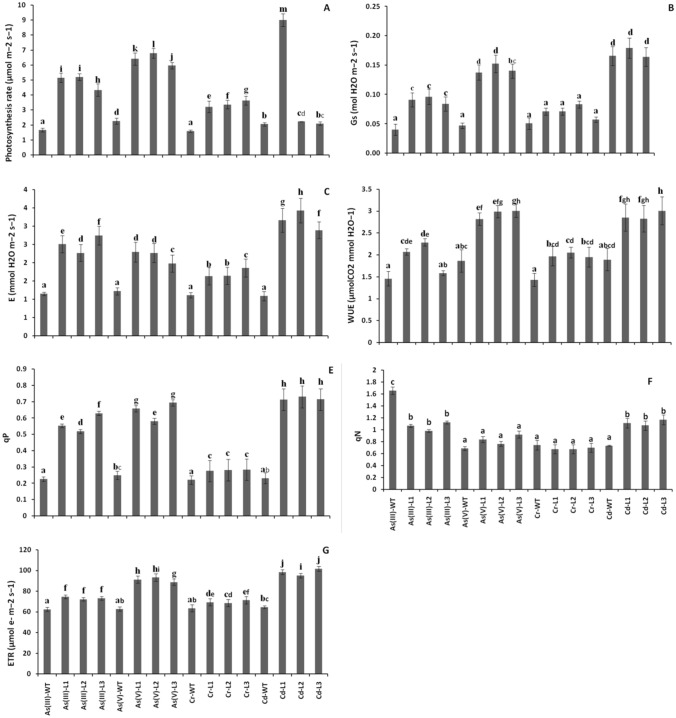

Transgenic Arabidopsis showed improved physiological performances under metal stress

Different environmental factors alter the physiological performance of plants. In the present study, the photosynthetic rate (A) of all the transgenic lines of the Arabidopsis plants was significantly increased against their respective WT exposed to heavy metals (Fig. 3A). Similarly, the stomatal conductance (G) was also significantly increased in all the transgenic lines against their respective WT treatments, except for Cr (Fig. 3B). The leaf transpiration (E), water use efficiency (WUE), and photochemical quenching (qP) were also increased in most of the treatment lines, as compared to their respective WT treatments (Fig. 3C–E). Among these parameters, Cd-treated transgenic lines showed the highest E and qP in the Arabidopsis plants. However, the non-photochemical quenching (qN) was significantly reduced in all the lines, as compared to their respective WT controls (Fig. 3F). On the other hand, all the transgenic lines showed an increased ETR with heavy metal treatment, as compared to their respective WT plants (Fig. 3G).

Fig. 3.

Physiological performance in transgenic lines and wild-type plants under metal stress. A Photosynthesis rate (A; µmol m−2 s−1), B Stomatal conductance (G; mol H2O m−2 s−1), C Leaf transpiration (E; mmol H2O m−2 s−1), D Water use efficiency (WUE; µmol CO2 mmol H2O−1), E Photochemical quenching (qP), F Non-photochemical quenching (qN), G Electron transport rate (ETR; µmol e− m−2 s−1)

Total accumulation of metals was affected by overexpression of MT1 gene in transgenic Arabidopsis lines

The accumulation of metals causes cellular toxicity. In our study, the As(III) accumulation was not significantly affected in transgenic lines (Fig. 4). However, the accumulation of As(V) was significantly increased in L2 and L3 in comparison to As(V)-WT. The Cr-treated transgenic lines showed a non-significant increase in L3 as compared to WT plants. All the transgenic lines of Cd-treated plants showed a significant increase in Cd accumulation compared to their WT. The maximum increased level of Cd accumulation was observed in transgenic L-3 line. Among all the heavy metal treatments, the transgenic lines highly increased the Cd accumulation, whereas the non-significant effect was observed with As(III).

Effect on cysteine: a stress-responsive amino acid

The sulfur-containing amino acid cysteine content was enhanced in overexpressing lines (Table S2), which was highest (96% higher with its control) in As(III)-L2 line. In the As(V)-treated lines, all the transgenic plants showed a higher content of cysteine as compared to As(V)-WT. The maximum content (74%) in comparison to WT was observed in As(V)-L2. The highest content of cysteine was observed in Cr treated transgenic lines, in which the Cr-L1 line showed the highest content (207%) as compared to WT plants. Similarly, the Cd-treated transgenic lines exhibited a higher level of cysteine in comparison to Cd-WT. The highest level (24.34%) was observed in Cd (L-2) line among all transgenic lines.

Discussion

In the environment, plants regularly interact with abiotic factors. Heavy metals, which are a notable environmental hazard (as edaphic pollutants), have a significant impact on the overall growth, metabolism, and eventually on the productivity of crops (Samuilov et al. 2016; Wani et al. 2018). Exposure to heavy metals in the plants causes oxidative stress leading to an alteration in molecular, biochemical, and physiological processes. Therefore, appropriate protective mechanisms to negate the toxic effects of these pollutants are essential for normal plant growth and development. In recent studies, different transgenic strategies have been used for the synthesis of metal chelators like phytochelatins, glutathione, organic acids, and MTs to enhance the plant tolerance against heavy metal stress (Kotrba et al. 2009; Sebastian et al. 2019). Among these metal chelators, MTs are involved in metal homeostasis because of their cysteine amino acids in their active sites. In animals, the role of MT is well defined, while in plants, its roles are still under investigation. MTs have been largely investigated against Cd toxicity, particularly in animal systems. Our study has tried to explore the specific role of the MT1 gene against four heavy metals [As (III), As (V), Cr (VI), and Cd].

Transgenic lines showed higher transcript level of MT1 gene against metal stress

The higher levels of the transcript of a gene in the cell indicate the pro-active role of the concerned gene for a specific function. In our study, a higher transcript level was observed in overexpression in response to heavy metals stress. The highest transcript level was observed against Cd toxicity, which shows its specificity towards Cd stress. However, its role against all combined major heavy metals stress is still to be investigated in plants. Apart from Cd, the presented study has also shown the higher transcript level of MT1 gene against different heavy metals; Cr(VI), As(III), and As(V), which indicates its involvement in the mitigation of toxicity by these metals. The order of transcript level was observed as Cd > Cr(VI) > As(V) > As(III), which shows the responsiveness of the MT1 gene to mitigate the stress of heavy metals. However, earlier studies indicate that plant MT1 is more specific against Cd (Zimeri et al. 2005; Yang et al. 2015; Li et al. 2016). In a study by Duan et al. (2019), the specificity of CsMT4 was reported against Cd metal toxicity in cucumber. In an earlier study, Pan et al. (2016) have also reported that Cd exposure regulates the expression of CsMTL2, while it remains unaffected by Zn exposure in cucumber plants.

Transgenic lines showed better phenotypic parameters against heavy metal stress

Abiotic and biotic stresses disrupt the cellular mechanisms as well as biochemical processes within the plant, leading to the alteration in growth and reduction in yield. In the present study, WT plants showed reduced length and biomass against heavy metal stress, while length and biomass were enhanced in the transgenic lines. In a study, Zhang et al. (2017) have reported that MT reduces cell death and enhances cell proliferation during Cd and Cu stress. Similarly, in our earlier study, MT1 was found to recover the growth of Arabidopsis plants against drought stress (Dubey et al. 2019). The accumulation of heavy metals leads to the inhibition of growth and development in plants. Heavy metals disrupt the biochemical as well as physiological processes required for the growth and development of plants. However, MT and other metalloproteinases are reported to be involved in the development of plants by regulating the process of metal homeostasis (Liu et al. 2017). MTs also chelate the heavy metals and sequester it into vacuoles of the plants, which reduce the toxicity and protect the related developmental factors (Clemens and Ma 2016). According to Anand et al. (2019) study, MT has a significant role in seed germination by regulating the signal transduction pathway in magneto primed tomato.

Over-expression of MT1 gene reduced the stress markers, enhanced antioxidants levels and cysteine content in the transgenic plants

The stress markers (TBARS, H2O2, and electrolyte leakage) are often enhanced during biotic and abiotic stresses. The abiotic factors such as heavy metals, drought, salinity, cold, and high light intensity induce the overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in plants. The generation of ROS disrupts the cellular biomolecules (lipids, nucleic acids, and proteins). The reaction of the reactive hydroxyl group with lipid bilayer leads to the oxidation of the membrane leading to the production of TBARS and thereby increasing the leakage of ions. Our study also showed a higher level of TBARS and electrolyte leakage in WT plants against heavy metal stress. However, the transgenic lines had reduced the level of TBARS and electrolyte leakage. Zhou et al. (2014) has reported that tobacco plants transformed with the MT gene reduce the TBARS level against Cd stress. MT defends cellular membrane injury by reacting with oxidant molecules using its sulfhydryl groups (Ruttkay-Nedecky et al. 2013). Simultaneously, MT also regulates the antioxidants to counter the oxidative stress induced by environmental factors. Metal exposure triggers the formation of more reactive oxygen species (ROS), resulting in oxidative stress in plants. During oxidative stress, plant cells shift their reducing state to the oxidizing state and thus synthesize antioxidant molecules to reverse the state. Plants synthesize mainly two antioxidant molecules i.e. Asc and GSH to maintain the reducing environment in the cell. The antioxidants serve as a strong defense mechanism in plants. In the antioxidant system, GSH and ascorbic acid play a vital role in maintaining the reducing environment of the cell against oxidative stress. GSH and ascorbic acid are also the co-substrates of the antioxidant molecules of enzymes, which directly reduce the level of ROS. In our study, Arabidopsis transformed with the MT1 gene exhibited a higher level of Asc/DHA and GSH/GSSG ratio against heavy metal stress. The higher level of Asc/DHA and GSH/GSSG ratio indicates that the cell is trying to sustain the reducing environment during oxidative stress (Foyer and Noctor 2011). Simultaneously, ascorbate and GSH dependent enzymes restrict the level of H2O2. As a ROS, H2O2 at higher levels causes large-scale cellular injury by reacting with biomolecules (Nakano and Asada 1981; Takeda et al. 1993; Kumar et al. 2016). The level of H2O2 was found to be higher in the WT while it was lower in overexpressing lines. The reduction of H2O2 may be due to the activation of antioxidant enzymes by MT1 gene. Some earlier studies have reported that the over-expression of the MT gene can regulate the activity of antioxidant enzymes in plants (Xue et al. 2009; Hassinen et al. 2011). The present study has also demonstrated the significant enhancement in the activity of antioxidant enzymes in plants transformed with the MT1 gene against all the heavy metal treatments. In the MT1 over-expressed lines, an increase in the activities of SOD, APX, GPX, and POD in Cd treated lines, whereas CAT was observed in As(V) and GRX in Cr treatment. Similarly, a study has also reported that tobacco plants over-expressing the SaMT2 gene enhance the activity of antioxidant enzymes to provide tolerance against Cd and Zn stress (Zhang et al. 2014).

Cysteine is a sulfur-containing amino acid that donates reduced sulfur to the essential biomolecules involved in defense mechanism and metal chelation (Ziller and Fraissinet-Tachet 2018). Simultaneously, cysteine and its derivatives play a vital role in maintaining cellular redox potential over the life cycle. During oxidative stress, the cell moves towards the oxidation state, where the cysteine-containing molecules such as GRX and GSH maintain the reducing environment of the cell (Dubey et al. 2016). In our study, the plants transformed with the MT1 gene significantly enhanced the cysteine content in the tissues against heavy metal stress. Plant MT is a cysteine-rich molecule involved in the tolerance mechanism (Grennan 2011). The over-expression of the MT1 gene might enhance the cysteine content to synthesize their MT proteins translated from its mRNA.

Transformation of Arabidopsis with MT1 gene enhanced the physiological responses

The physiological responses such as photosynthetic rate, photochemical quenching, non-photochemical quenching, and stomatal conductance vary according to environmental stresses. The alteration of physiological performance during stress can reduce the development and yield of plants. Several earlier studies have reported that the plants exposed to different stresses reduced their physiological performance (Shanying et al. 2017; Arbona et al. 2017; Szymańska et al. 2017). In our study, Arabidopsis plants transformed with the MT1 gene enhanced the A, G, E, WUE, qP and reduced the qN against heavy metal stress. The different stress factors disrupt the carbon metabolism in plants, which also limits the physiological responses of the plants (Lawlor and Cornic 2002). Heavy metal stress directly damages the chloroplast structure. The damage to the photosynthetic apparatus leads to a decline in the transpiration, assimilation rate, and intercellular CO2 (Bacelar et al. 2007). The factor restricting stress response may recover the physiological response in the plants. In our study, the physiological responses were enhanced by the transformation with the MT1 gene, indicating the involvement of the MT1 in the amelioration of heavy metal stress. In our research, contrary to the other physiological parameters, qN was found to be reduced in the transgenic lines. Non-photochemical quenching occurs to save the photosynthesis apparatus by inactivating the PSII (Linger et al. 2005). The accumulation of heavy metals damages the photosynthetic apparatus, and qN starts to prevent its damage by enhancing its levels (Hanaka et al. 2015). In our study, the lower qN in transgenic lines, as compared to WT plants treated with heavy metals, reveal the defense role of MT to save the photosynthetic apparatus from heavy metal toxicity.

Over-expression of MT1 gene alters heavy metal accumulation in Arabidopsis

Plants accumulate metals to deal with their biochemical as well as physiological functions (Emamverdian et al. 2015). Simultaneously, the root transportation system also accumulates unnecessary and toxic heavy metals such as Cd, As, Cr, Pd, which leads to cellular damage. The heavy metals accumulate in plants by selective or non-selective transporters, according to size and analogous to other metals (Hall 2002). The accumulation of metals is regulated by the threshold level of the metals and signal precursors. Sometimes the cellular components such as MT, GRX, and GABA also regulate the transportation of metals (Holmgren 1989; Verma et al. 2016; Kumar et al. 2016; Ziller and Fraissinet-Tachet 2018). In our study, the over-expression of the MT1 gene affected the accumulation in Arabidopsis after exposure to all major heavy metals. Amongst all the heavy metals viz. [As(III), As(V), Cr(VI), and Cd], the level of As(V) and Cd(VI) was significantly enhanced in most of the transgenic lines. The alteration of heavy metal accumulation might be due to the specificity of heavy metals and the involvement of the MT1 gene in the transportation system of the plant. A study has reported that Arabidopsis plants transformed with SsMT2 elevated the accumulation of Cd in the tissues, which was positively correlated with the expression of the MT gene (Jin et al. 2017). Another study has also shown that the mutant of Arabidopsis lacking MT1 gene expression reduced the accumulation of Cu by 30% compared to the WT plants (Guo et al. 2008). However, Zimeri et al. (2005) have reported that MT1 knockdown lines exhibited hypersensitivity towards Cd and reduced the level of As, Cd, and Zn, as compared to WT plants, whereas Cu and Fe accumulation were unaffected.

Conclusions

The study has explored the role of the MT1 gene against all major toxic heavy metals. The over-expressing lines showed enhanced tolerance against all the heavy metals. The defense system responsible for metal tolerance was elevated in the transgenic lines over-expressing MT1, compared to WT plants. The elevated physiological, as well as antioxidant parameters and lower level of stress markers in transgenic lines demonstrate the potential role of MT1 in heavy metal tolerance. Similarly, the sulfur-containing amino acid cysteine was higher in transgenic lines, suggesting that MT1 actively regulates the thiol-dependent mechanism to reduce the heavy metals toxicity in plants. Overall, the results indicated that the MT1 gene could be a potential candidate gene for the mitigation of heavy metals by plants.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The project supervisor (IS) and SKB, SM are very grateful to Director, CSIR-NBRI for infrastructure. CSIR, New Delhi and UGC, New Delhi is greatly acknowledged for research fellowships. CSIR-NBRI Manuscript Number: CSIR-NBRI_MS/2021/09/07.

Funding

The research work was supported by a research Grant (BSC 0204) from C.S.I.R., New Delhi, India.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Anand A, Kumari A, Thakur M, Koul A. Hydrogen peroxide signaling integrates with phytohormones during the germination of magnetoprimed tomato seeds. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-45102-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson ME. Determination of glutathione and glutathione disulfide in biological samples. Methods Enzymol. 1985;113:548–555. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(85)13073-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbona V, Manzi M, Zandalinas SI, Vives-Peris V, Pérez-Clemente RM, Gómez-Cadenas A (2017) Physiological, metabolic, and molecular responses of plants to abiotic stress. In: Stress signaling in plants: genomics and proteomics perspective, vol. 2. Springer, pp 1–35

- Bacelar EA, Moutinho-Pereira JM, Gonçalves BC, Ferreira HF, Correia CM. Changes in growth, gas exchange, xylem hydraulic properties and water use efficiency of three olive cultivars under contrasting water availability regimes. Environ Exp Bot. 2007;60(2):183–192. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2006.10.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bandurska H. Does proline accumulated in leaves of water deficit stressed barley plants confine cell membrane injury? I. Free proline accumulation and membrane injury index in drought and osmotically stressed plants. Acta Physiol Plant. 2000;22(4):409–415. doi: 10.1007/s11738-000-0081-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchamp C, Fridovich I. Superoxide dismutase: improved assays and an assay applicable to acrylamide gels. Anal Biochem. 1971;44(1):276–287. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(71)90370-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benatti MR, Yookongkaew N, Meetam M, Guo WJ, Punyasuk N, AbuQamar S, Goldsbrough P. Metallothionein deficiency impacts copper accumulation and redistribution in leaves and seeds of Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 2014;202(3):940–951. doi: 10.1111/nph.12718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72(1–2):248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandlee JM, Scandalios JG. Analysis of variants affecting the catalase developmental program in maize scutellum. Theor Appl Genet. 1984;69(1):71–77. doi: 10.1007/bf00262543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatthai M, Kaukinen KH, Tranbarger TJ, Gupta PK, Misra S. The isolation of a novel metallothionein-related cDNA expressed in somatic and zygotic embryos of Douglas-fir: regulation by ABA, osmoticum, and metal ions. Plant Mol Biol. 1997;34(2):243–254. doi: 10.1023/A:1005839832096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chugh LK, Sawhney SK. Photosynthetic activities of Pisum sativum seedlings grown in presence of cadmium. Plant Physiol Biochem. 1999;37(4):297–303. doi: 10.1016/S0981-9428(99)80028-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clemens S, Ma JF. Toxic heavy metal and metalloid accumulation in crop plants and foods. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2016;67:489–512. doi: 10.1146/annrev-arplant-043015-112301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough SJ, Bent AF. Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1998;16(6):735–743. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobbett C, Goldsbrough P. Phytochelatins and metallothioneins: roles in heavy metal detoxification and homeostasis. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2002;53(1):159–182. doi: 10.1146/annrev.arplant.53.100301.135154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan L, Yu J, Xu L, Tian P, Hu X, Song X, Pan Y. Functional characterization of a type 4 metallothionein gene (CsMT4) in cucumber. Hort Plant J. 2019;5(3):120–128. doi: 10.1016/j.hpj.2019.04.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dubey AK, Kumar N, Sahu N, Verma PK, Chakrabarty D, Behera SK, Mallick S. Response of two rice cultivars differing in their sensitivity towards arsenic, differs in their expression of glutaredoxin and glutathione-S-transferase genes and antioxidant usage. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2016;124:393–405. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2015.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubey AK, Kumar N, Kumar A, Ansari MA, Ranjan R, Meenakshi GA, Sahu N, Pandey V, Behera SK, Mallick S, Pande V, Sanyal I. Over-expression of CarMT gene modulates the physiological performance and antioxidant defense system to provide tolerance against drought stress in Arabidopsis thaliana L. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2019;171:54–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2018.12.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emamverdian A, Ding Y, Mokhberdoran F, Xie Y. Heavy metal stress and some mechanisms of plant defense response. Sci World J. 2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/756120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foyer CH, Noctor G. Ascorbate and glutathione: the heart of the redox hub. Plant Physiol. 2011;155(1):2–18. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.167569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaitonde MK. A spectrophotometric method for the direct determination of cysteine in the presence of other naturally occurring amino acids. Biochem J. 1967;104(2):627–633. doi: 10.1042/bj1040627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg N, Singla P. Arsenic toxicity in crop plants: physiological effects and tolerance mechanisms. Environ Chem Lett. 2011;9(3):303–321. doi: 10.1007/s10311-011-0313-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grennan AK. Metallothioneins, a diverse protein family. Plant Physiol. 2011;155(4):1750–1751. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.900407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo WJ, Bundithya W, Goldsbrough PB. Characterization of the Arabidopsis metallothionein gene family: tissue-specific expression and induction during senescence and in response to copper. New Phytol. 2003;1:369–381. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-8137.2003.00813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo WJ, Meetam M, Goldsbrough PB. Examining the specific contributions of individual Arabidopsis metallothioneins to copper distribution and metal tolerance. Plant Physiol. 2008;146(4):1697–1706. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.115782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall JÁ. Cellular mechanisms for heavy metal detoxification and tolerance. J Exp Bot. 2002;53(366):1–1. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/53.366.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanaka A, Maksymiec W, Bednarek W. The effect of methyl jasmonate on selected physiological parameters of copper-treated Phaseolus coccineus plants. Plant Growth Regul. 2015;77(2):167–177. doi: 10.1007/s10725-015-0048-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hassinen VH, Tervahauta AI, Schat H, Kärenlampi SO. Plant metallothioneins–metal chelators with ROS scavenging activity? Plant Biol. 2011;13(2):225–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1438-8677.2010.00398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges DM, DeLong JM, Forney CF, Prange RK. Improving the thiobarbituric acid-reactive-substances assay for estimating lipid peroxidation in plant tissues containing anthocyanin and other interfering compounds. Planta. 1999;207(4):604–611. doi: 10.1007/s004250050524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmgren A. Thioredoxin and glutaredoxin systems. J Biol Chem. 1989;264(24):13963–13966. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)71625-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaishankar M, Mathew BB, Shah MS, Gowda KR (2014) Biosorption of few heavy metal ions using agricultural wastes. J Environ Pollut Hum Health 2(1):1–6. 10.12691/jephh-2-1-1

- Jin S, Xu C, Li G, Sun D, Li Y, Wang X, Liu S. Functional characterization of a type 2 metallothionein gene, SsMT2, from alkaline-tolerant Suaeda salsa. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):1–1. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-18263-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jyothishwaran G, Kotresha D, Selvaraj T, Srideshikan SM, Rajvanshi PK, Jayabaskaran C. A modified freeze–thaw method for efficient transformation of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Curr Sci. 2007;93(6):770–772. [Google Scholar]

- Kampfenkel K, Van Montagu M, Inzé D. Extraction and determination of ascorbate and dehydroascorbate from plant tissue. Anal Biochem. 1995;225(1):165–167. doi: 10.1006/abio.1995.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato M, Shimizu S. Chlorophyll metabolism in higher plants. VII. Chlorophyll degradation in senescing tobacco leaves; phenolic-dependent peroxidative degradation. Can J Bot. 1987;65(4):729–735. doi: 10.1139/b87-097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Katz SA, Salem H. The biological and environmental chemistry of chromium. Weinheim: VCH Publishers; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kimura T, Kambe T. The functions of metallothionein and ZIP and ZnT transporters: an overview and perspective. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(3):336. doi: 10.3390/ijms17030336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh MJ, Kim HJ. The effect of metallothionein on the activity of enzymes involved in removal of reactive oxygen species. Bull Korean Chem Soc. 2001;22(4):362–366. [Google Scholar]

- Kotaś J, Stasicka ZJ. Chromium occurrence in the environment and methods of its speciation. Environ Poll. 2000;107(3):263–283. doi: 10.1016/S0269-7491(99)00168-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotrba P, Najmanova J, Macek T, Ruml T, Mackova M. Genetically modified plants in phytoremediation of heavy metal and metalloid soil and sediment pollution. Biotech Adv. 2009;27(6):799–810. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar N, Dubey AK, Jaiswal PK, Sahu N, Behera SK, Tripathi RD, Mallick S. Selenite supplementation reduces arsenate uptake greater than phosphate but compromises the phosphate level and physiological performance in hydroponically grown Oryza sativa L. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2016;35(1):163–172. doi: 10.1002/etc.3171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafitte R. Relationship between leaf relative water content during reproductive stage water deficit and grain formation in rice. Field Crops Res. 2002;76(2–3):165–174. doi: 10.1016/S0378-4290(02)00037-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert M, Leven BA, Green RM (2000) New methods of cleaning up heavy metal in soils and water. Environ Sci Technol Briefs Citiz 1–3.

- Lawlor DW, Cornic G. Photosynthetic carbon assimilation and associated metabolism in relation to water deficits in higher plants. Plant Cell Environ. 2002;25(2):275–294. doi: 10.1046/j.0016-8025.2001.00814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesser MP. Oxidative stress in marine environments: biochemistry and physiological ecology. Annu Rev Physiol. 2006;68:253–278. doi: 10.1146/annrev.physiol.68.040104.110001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li LS, Meng YP, Cao QF, Yang YZ, Wang F, Jia HS, Wu SB, Liu XG. Type 1 metallothionein (ZjMT) is responsible for heavy metal tolerance in Ziziphus jujuba. Biochem Mosc. 2016;81(6):565–573. doi: 10.1134/S000629791606002X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linger P, Ostwald A, Haensler J. Cannabis sativa L. growing on heavy metal contaminated soil: growth, cadmium uptake and photosynthesis. Biol Plant. 2005;49(4):567–576. doi: 10.1007/s10535-005-0051-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu SH, Zeng GM, Niu QY, Liu Y, Zhou L, Jiang LH, Tan XF, Xu P, Zhang C, Cheng M. Bioremediation mechanisms of combined pollution of PAHs and heavy metals by bacteria and fungi: a mini review. Bioresource Technol. 2017;224:25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2016.11.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma JF, Yamaji N, Mitani N, Xu XY, Su YH, McGrath SP, Zhao FJ. Transporters of arsenite in rice and their role in arsenic accumulation in rice grain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(29):9931–9935. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802361105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallick S, Kumar N, Singh AP, Sinam G, Yadav RN, Sinha S. Role of sulfate in detoxification of arsenate-induced toxicity in Zea mays L. (SRHM 445): nutrient status and antioxidants. J Plant Interact. 2013;8(2):140–154. doi: 10.1080/17429145.2012.734863. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muehe EM, Eisele JF, Daus B, Kappler A, Harter K, Chaban C. Are rice (Oryza sativa L.) phosphate transporters regulated similarly by phosphate and arsenate? A comprehensive study. Plant Mol Biol. 2014;85(3):301–316. doi: 10.1007/s11103-014-0186-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano Y, Asada K. Hydrogen peroxide is scavenged by ascorbate-specific peroxidase in spinach chloroplasts. Plant Cell Physiol. 1981;22(5):867–880. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a076232. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Norton GJ, Islam MR, Deacon CM, Zhao FJ, Stroud JL, McGrath SP, Islam S, Jahiruddin M, Feldmann J, Price AH, Meharg AA. Identification of low inorganic and total grain arsenic rice cultivars from Bangladesh. Environ Sci Technol. 2009;43(15):6070–6075. doi: 10.1021/es901121j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Y, Pan Y, Zhai J, Xiong Y, Li J, Du X, Su C, Zhang X. Cucumber metallothionein-like 2 (CsMTL2) exhibits metal-binding properties. Genes. 2016;7(12):106. doi: 10.3390/genes7120106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peralta JR, Gardea-Torresdey JL, Tiemann KJ, Gomez E, Arteaga S, Rascon E, Parsons JG. Uptake and effects of five heavy metals on seed germination and plant growth in alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) Bullet Environ Contamin Toxicol. 2001;66(6):727–734. doi: 10.1007/s00128-001-0069-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad MN. Cadmium toxicity and tolerance in vascular plants. Environ Exp Bot. 1995;35(4):525–545. doi: 10.1016/0098-8472(95)00024-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ruttkay-Nedecky B, Nejdl L, Gumulec J, Zitka O, Masarik M, Eckschlager T, Stiborova M, Adam V, Kizek R. The role of metallothionein in oxidative stress. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14(3):6044–6066. doi: 10.3390/ijms14036044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sairam RK, Rao KV, Srivastava GC. Differential response of wheat genotypes to long term salinity stress in relation to oxidative stress, antioxidant activity and osmolyte concentration. Plant Sci. 2002;163(5):1037–1046. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9452(02)00278-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Samuilov S, Lang F, Djukic M, Djunisijevic-Bojovic D, Rennenberg H. Lead uptake increases drought tolerance of wild type and transgenic poplar (Populus tremula x P. alba) overexpressing gsh 1. Environ Poll. 2016;216:773–785. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2016.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebastian A, Shukla P, Nangia AK, Prasad MN (2019) Transgenics in phytoremediation of metals and metalloids: from laboratory to field. In: Transgenic plant technology for remediation of toxic metals and metalloids. Academic Press, pp 3–22. 10.1016/B978-0-12-814389-6.00001-8

- Sgherri C, Milone MT, Clijsters H, Navari-Izzo F. Antioxidative enzymes in two wheat cultivars, differently sensitive to drought and subjected to sub-symptomatic copper doses. J Plant Physiol. 2001;158(11):1439–1447. doi: 10.1078/0176-1617-00543. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shahid M, Dumat C, Khalid S, Niazi NK, Antunes PM. Cadmium bioavailability, uptake, toxicity and detoxification in soil-plant system. Rev Environ Contamin Toxicol. 2016;241:73–137. doi: 10.1007/398_2016_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanker AK, Cervantes C, Loza-Tavera H, Avudainayagam S. Chromium toxicity in plants. Environ Int. 2005;31(5):739–753. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanying HE, Xiaoe YA, Zhenli HE, Baligar VC. Morphological and physiological responses of plants to cadmium toxicity: a review. Pedosphere. 2017;27(3):421–438. doi: 10.1016/S1002-0160(17)60339-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Szymańska R, Ślesak I, Orzechowska A, Kruk J. Physiological and biochemical responses to high light and temperature stress in plants. Environ Exp Bot. 2017;139:165–177. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2017.05.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda T, Nakano Y, Shigeoka S. Effects of selenite, CO2 and illumination on the induction of selenium-dependent glutathione peroxidase in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Sci. 1993;94(1–2):81–88. doi: 10.1016/0168-9452(93)90009-O. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turner NC. Techniques and experimental approaches for the measurement of plant water status. Plant Soil. 1981;58(1):339–366. doi: 10.1007/BF02180062. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Velikova V, Yordanov I, Edreva A. Oxidative stress and some antioxidant systems in acid rain-treated bean plants: protective role of exogenous polyamines. Plant Sci. 2000;151(1):59–66. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9452(99)00197-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Verma PK, Verma S, Pande V, Mallick S, Deo Tripathi R, Dhankher OP, Chakrabarty D (2016) Overexpression of rice glutaredoxin OsGrx_C7 and OsGrx_C2. 1 reduces intracellular arsenic accumulation and increases tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Front Plant Sci 7:740. 10.3389/fpls.2016.00740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wani W, Masoodi KZ, Zaid A, Wani SH, Shah F, Meena VS, Wani SA, Mosa KA. Engineering plants for heavy metal stress tolerance. Rend Lincei Sci Fis Nat. 2018;29(3):709–723. doi: 10.1007/s12210-018-0702-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xue T, Li X, Zhu W, Wu C, Yang G, Zheng C. Cotton metallothionein GhMT3a, a reactive oxygen species scavenger, increased tolerance against abiotic stress in transgenic tobacco and yeast. J Exp Bot. 2009;60(1):339–349. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ern291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang M, Zhang F, Wang F, Dong Z, Cao Q, Chen M. Characterization of a type 1 metallothionein gene from the stresses-tolerant plant Ziziphus jujuba. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16(8):16750–16762. doi: 10.3390/ijms160816750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Zhang M, Tian S, Lu L, Shohag MJ, Yang X. Metallothionein 2 (SaMT2) from Sedum alfredii Hance confers increased Cd tolerance and accumulation in yeast and tobacco. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(7):e102750. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Lv S, Xu H, Hou D, Li Y, Wang F. H2O2 is involved in the metallothionein-mediated rice tolerance to copper and cadmium toxicity. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(10):2083. doi: 10.3390/ijms18102083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao K, Liu X, Xu J, Selim HM. Heavy metal contaminations in a soil–rice system: identification of spatial dependence in relation to soil properties of paddy fields. J Hazard Mat. 2010;181(1–3):778–787. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2010.05.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou B, Yao W, Wang S, Wang X, Jiang T. The metallothionein gene, TaMT3, from Tamarix androssowii confers Cd2+ tolerance in tobacco. Intl J Mol Sci. 2014;15(6):10398–10409. doi: 10.3390/ijms150610398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziller A, Fraissinet-Tachet L. Metallothionein diversity and distribution in the tree of life: a multifunctional protein. Metallomics. 2018;10(11):1549–1559. doi: 10.1039/c8mt00165k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimeri AM, Dhankher OP, McCaig B, Meagher RB. The plant MT1 metallothioneins are stabilized by binding cadmiums and are required for cadmium tolerance and accumulation. Plant Mol Biol. 2005;58(6):839–855. doi: 10.1007/s11103-005-8268-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.