Abstract

Background

Feeding intolerance is a common clinical problem among preterm infants. It may be an early sign of necrotising enterocolitis, sepsis or other serious gastrointestinal conditions, or it may result from gut immaturity with delayed passage of meconium. Glycerin laxatives stimulate passage of meconium by acting as an osmotic dehydrating agent and increasing osmotic pressure in the gut; they stimulate rectal contraction, potentially reducing the incidence of feeding intolerance.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness and safety of glycerin laxatives (enemas/suppositories) for prevention or treatment of feeding intolerance in very low birth weight (VLBW) infants.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2015, Issue 4), MEDLINE, EMBASE and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL). We restricted our search to all randomised controlled trials and applied no language restrictions. We searched the references of identified studies and reviews on this topic and handsearched for additional articles. We searched the database maintained by the US National Institutes of Health (www.clinicaltrials.gov) and European trial registries to identify ongoing trials.

Selection criteria

We considered only randomised or quasi‐randomised controlled trials that enrolled preterm infants < 32 weeks' gestational age (GA) and/or < 1500 g birth weight. We included trials if they administered glycerin laxatives and measured at least one prespecified clinical outcome.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methods of The Cochrane Collaboration and its Neonatal Group to assess methodological quality of trials, to collect data and to perform analyses.

Main results

We identified three trials that evaluated use of prophylactic glycerin laxatives in preterm infants. We identified no trials that evaluated therapeutic use of glycerin laxatives for feeding intolerance. Our review showed that prophylactic administration of glycerin laxatives did not reduce the time required to achieve full enteral feeds and did not influence secondary outcomes, including duration of hospital stay, mortality and weight at discharge. Prophylactic administration of glycerin laxatives resulted in failure of fewer infants to pass stool over the first 48 hours. Included trials reported no adverse events.

Authors' conclusions

Our review of available evidence for glycerin laxatives does not support the routine use of prophylactic glycerin laxatives in clinical practice. Additional studies are needed to confirm or refute the effectiveness and safety of glycerin laxatives for prevention or treatment of feeding intolerance in VLBW infants.

Keywords: Humans; Infant, Very Low Birth Weight; Enema; Enema/methods; Enteral Nutrition; Enteral Nutrition/adverse effects; Gestational Age; Glycerol; Glycerol/therapeutic use; Laxatives; Laxatives/therapeutic use; Meconium; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Suppositories

Plain language summary

Glycerin laxatives for prevention or treatment of feeding intolerance in very low birth weight infants

Review question: Are glycerin laxatives (enemas/suppositories) safe and effective for prevention or treatment of feeding intolerance in very low birth weight (VLBW) infants?

Background: Preterm babies are at increased risk of feeding intolerance. Factors that contribute to feeding intolerance are many and include immature motility of the gut and increased viscosity of meconium. Enhancement of passage of the first stool (meconium) might enhance the ability of the preterm infant to tolerate feeds and might help reduce time spent receiving intravenous fluids.

Study characteristics: Our review identified three studies that addressed the use of glycerin suppositories to prevent feeding intolerance in preterm infants.

Key findings: We found that a glycerin enema given to preterm infants prophylactically did not shorten time to full feeding, nor did it decrease time to discharge. However, available data are too limited to allow a strong conclusion.

Conclusions: Our review of available evidence for glycerin laxatives does not support routine prophylactic use of glycerin laxatives in clinical practice. Additional studies are needed to confirm or refute the effectiveness and safety of glycerin laxatives for prevention or treatment of feeding intolerance in VLBW infants.

Background

Description of the condition

Feeding intolerance, a common clinical problem among preterm infants, occurs in all infants born before 29 weeks (Ringer 1996). It may be an early sign of necrotising enterocolitis (NEC), sepsis or other serious conditions, or it may result from gut immaturity. Feeding intolerance is the most important diagnostic feature of NEC (Bell 1978) and should be treated early to prevent its progression. Although it is a common problem, no definition of feeding intolerance has been universally accepted (Moore 2011), and current definitions are based on assessment of the quantity and colour of gastric residuals and associated clinical manifestations (Jadcherla 2002). Feeding intolerance usually manifests with gastric residuals, vomiting, abdominal distension and delay in passage of meconium (Newell 2000; Patole 2005). Factors that contribute to feeding intolerance include incompetent lower oesophageal sphincter, small gastric capacity and delayed gastric emptying time, intestinal hypomotility (Mansi 2011), immaturity of intestinal motor mechanisms (Newell 2000) and increased viscosity of meconium. Timing of the first and last meconium stools is critical for oral feeding tolerance and proper gastrointestinal function (Meetze 1993). Obstruction of deep intestinal segments by tenacious, sticky meconium frequently leads to gastric residuals, distended abdomen and delayed food passage (Weaver 1993). In contrast to term infants, many preterm infants pass their first meconium only after considerable delay ‐ up to 27 days (median 43 hours) (Meetze 1993; Wang 1994). Consequences of feeding intolerance include hyperbilirubinaemia, prolonged need for total parenteral nutrition (TPN), infection, liver damage secondary to TPN and prolonged stay in the hospital (Stoll 2002; Unger 1986). Therefore, the priority is to establish full enteral feeds as soon as possible in preterm infants (Kaufman 2003). In an observational study in 2007, Shim et al reported that routine use of glycerin enema in infants resulted in full enteral feeds earlier than in the control group (median 16.0 vs 22.9 days; P value < 0.001) with a hazard ratio (HR) of 2.9 (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.8 to 4.8). This difference was greater for infants with birth weight < 1000 g (median 17.3 vs 28.1 days; P value < 0.001). Investigators also reported that the rate of sepsis was lower for very low birth weight (VLBW) infants in the glycerin enema group than for those in the control group (7.7% vs 27.8%; P value = 0.02) (Shim 2007).

Description of the intervention

Glycerin laxatives in the form of enemas or suppositories are widely used in neonatal intensive care units (Zenk 1993). Glycerin suppositories contain purified water, sodium hydroxide and stearic acid and 90% glycerin. They act by virtue of the mildly irritant action of glycerol (BNF 2010) and are used to enhance bowel evacuation to prevent or manage feeding intolerance. Glycerin laxatives are administered per rectum manually. The safety of glycerin has been proved by long‐term clinical use (Shim 2007). It is relatively inexpensive and does not require a medical device for administration nor for close monitoring. Possible side effects of glycerin include local irritation and hyperosmotic damage to bowel epithelial cells, which may manifest as haematochezia, occult bleeding or even perforation.

How the intervention might work

Glycerin laxatives stimulate the passage of meconium by acting as an osmotic dehydrating agent and by increasing osmotic pressure in the gut; they stimulate rectal contraction as well. Through its osmotic effects, glycerin softens, lubricates and facilitates elimination of inspissated faeces (Gilman 1990).

Why it is important to do this review

In a recent review on glycerin use among preterm infants, review authors identified two studies: one randomised controlled trial (RCT) and one observational study. They concluded that evidence regarding effectiveness of glycerin laxatives for improving feeding intolerance in infants at ≤ 32 weeks' gestational age or weighing ≤ 1500 g at birth is inconclusive (Shah 2011). Despite widespread utilization of glycerin laxatives in VLBW infants, their effectiveness remains to be proved. Therefore, a critical review of the literature is needed to assess their effectiveness and safety in preventing or treating feeding intolerance among VLBW infants.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness and safety of glycerin laxatives (enemas/suppositories) for prevention or treatment of feeding intolerance in VLBW infants.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised or quasi‐randomised controlled trials undertaken to evaluate the effectiveness of glycerin laxatives for feeding intolerance in VLBW infants.

Types of participants

We included studies of VLBW infants (< 1500 g at birth) who received glycerin laxatives for preventing or treating feeding intolerance. We accepted all definitions of feeding intolerance.

For studies using gestational age only, we accepted ≤ 32 weeks as equivalent to VLBW infants.

For trials using glycerin for prevention of feeding intolerance, we accepted age of enrolment up to 72 hours of age.

For studies using glycerin for treatment of feeding intolerance, we included infants at any postnatal age.

Types of interventions

Studies compared administration of prophylactic or therapeutic glycerin laxatives versus placebo or no treatment in VLBW infants. For the purpose of this review, we accepted any dose, preparation or mode of administration of glycerin enemas/suppositories.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Time to full enteral feeds (days) (tolerating ≥ 120 mL/kg/d of enteral feeds with no additional IV fluids nor TPN).

Secondary outcomes

Duration of hospital stay (days).

Mortality (death during hospital stay).

Stage II or III NEC (per Bell's criteria) (Bell 1978).

Retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) (any stage) (ICCROP 2005).

Chronic lung disease (CLD) defined as need for ventilatory support or oxygen at 36 weeks post menstrual age (PMA).

Patent ductus arteriosus (PDA).

Intraventricular haemorrhage (IVH) (grade ≥ 2) (Papile 1978).

Passage of first stool > 48 hours after birth.

Weight at discharge home (g/d).

Late‐onset sepsis (positive blood or cerebrospinal fluid cultures beyond 72 hours of age) (Stoll 2004).

Duration of TPN (days).

Cholestasis (defined as serum conjugated bilirubin concentration > 1.0 mg/dL (17.1 micromol/L) with total serum bilirubin < 5.0 mg/dL (85.5 micromol/L) or > 20% of total serum bilirubin with total serum bilirubin > 5.0 mg/dL (85.5 micromol/L)) at any time during hospital stay.

Any reported adverse effects (e.g. diarrhoea, colonic perforation, malabsorption, rectal bleeding, rectal trauma).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We formulated a comprehensive and exhaustive search strategy in an attempt to identify all relevant studies, regardless of language or publication status (published, unpublished, in press or in progress). We searched the following databases: the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2015, Issue 4), MEDLINE (1950 to April 2015), EMBASE (1980 to April 2015) and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (1982 to April 2015). We restricted our search to all RCTs and applied no language restrictions. The search strategy included text/Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms (“preterm” OR “premature” OR “very low birth weight” OR “VLBW” OR “neonate” OR “newborn” OR “infan*”) AND (“Glycerin enema” OR “suppository” OR “glycerol”).

Searching other resources

We handsearched references from identified studies and reviews on this topic to look for additional articles. We searched the database maintained by the US National Institutes of Health (www.clinicaltrials.gov) and European trial registries to identify ongoing trials whose methods met the criteria for inclusion in this review and recorded these trials for use in future updates. We excluded the following types of articles: letters (without original data), editorials, reviews, lectures and commentaries.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Review authors independently (JA, VS) reviewed all identified citations (study titles and abstracts) retrieved by the search strategy for relevance to the topic of this review on the basis of study design, types of participants, interventions provided and outcome measures assessed. We removed duplicate trials and resolved disagreements or discrepancies by discussion and by consultation with a third review author (KA). We included reasons for exclusion of potentially relevant studies in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Data extraction and management

We designed a data extraction form, and review authors extracted data directly onto the form. Extracted data included authors and citation, study location, gestational age of participants, birth weight, postnatal age at enrolment, inclusion/exclusion criteria within each study, types and doses of glycerin laxatives used, sample size for intervention and control groups and outcomes data (effectiveness and adverse events). We resolved discrepancies involving data extraction by discussion and by decision of a third review author (KA).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed risk of bias of included studies using the method recommended by The Cochrane Collaboration (Higgins 2011). We requested additional information from trial authors as necessary to clarify methods and results. We assessed each study according to the following domains.

-

Sequence generation (Was the allocation sequence adequately generated?) might lead to selection bias (biased allocation to interventions) resulting from inadequate generation. We describe for each included study methods used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups. We assessed methods as:

low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table, computer random number generator);

high risk of bias (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth, hospital or clinic record number); or

unclear risk of bias.

-

Allocation concealment (Was allocation adequately concealed?) might lead to selection bias (biased allocation to interventions) resulting from inadequate concealment of allocations before assignment. We describe for each included study methods used to conceal the allocation sequence in sufficient detail and discuss whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during, recruitment, or changed after assignment. We assessed methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomisation, consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

high risk of bias (open random allocation, unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation, date of birth); or

unclear risk of bias.

-

Blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessors (Was knowledge of the allocated intervention adequately prevented during the study?) might lead to performance bias caused by knowledge of allocated interventions by participants and personnel during the study, or detection bias resulting from knowledge of allocated interventions by outcome assessors. We assessed methods as:

low risk of bias, high risk of bias, unclear risk of bias for participants;

low risk of bias, high risk of bias for personnel; or

unclear risk of bias for personnel.

-

Incomplete outcome data (Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed?) might lead to attrition bias associated with the quantity, nature or handling of incomplete outcome data. We categorised completeness as:

low risk: < 20% missing data;

high risk: ≥ 20% missing data; or

unclear risk.

-

Selective outcome reporting (Are reports of the study free of the suggestion of selective outcome reporting?) might lead to reporting bias resulting from selective outcome reporting. We describe for each included study how we examined the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we discovered. We assessed methods as:

low risk of bias (when it is clear that all of the study’s prespecified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest for the review have been reported);

high risk of bias (when not all of the study’s prespecified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not prespecified; outcomes of interest were reported incompletely and so cannot be used; or study failed to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported); or

unclear risk of bias.

-

Other sources of bias (Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at high risk of bias?). We describe for each included study important concerns that we have about other possible sources of bias. We assessed whether each study was free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias and determined:

low risk of other bias;

high risk of other bias; or

unclear risk of other bias.

We performed an overall assessment of each study on the basis of findings in these domains. Two review authors (JA, VS) assessed each domain according to preset criteria and judges studied as having "low risk of bias", "high risk of bias" or "unclear" (uncertain) risk of bias. We resolved discrepancies in judgement by discussion. Review authors were not blinded to study authors, locations of studies, author funding or study acknowledgements.

Measures of treatment effect

We calculated risk ratio (RR), risk difference (RD) and the number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) or the number need to treat for an additional harmful outcome (NNHB), along with the 95% confidence interval (CI) for dichotomous outcomes. For continuous outcomes, we expressed the treatment effect weighted mean difference (WMD), along with 95% CI.

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis is the participating infant for individually randomised trials and the neonatal unit (or subunit) for cluster‐randomised trials.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted the primary author of the study to request additional data when data were missing. Two review authors estimated values from the graphs when studies presented results graphically and it was not possible to reach study authors, or when study authors were contacted but did not provide original data. If the numbers were not similar, we presented results as descriptive data in the Results section. When results were provided as median and range, we converted data to mean and standard deviation using established methods (Hozo 2005). We conducted a sensitivity analysis to determine the impact of imputed data.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed between‐study heterogeneity using I‐squared (I2) and Chi2 statistics (Higgins 2003). We categorised I2 values in the following manner: less than 25%: not important; 25% to 49%: representing low heterogeneity; 50% to 74%: representing moderate heterogeneity; and 75% to 100%: representing high heterogeneity (Higgins 2011). If I2 values were greater than 75%, we considered the magnitude and accompanying P value in the overall interpretation. In addition, two or more review authors reassessed the included studies to determine whether qualitative differences leading to heterogeneity would prevent pooling of study results.

Assessment of reporting biases

We describe how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias. If the protocol was available, we compared outcomes in the protocol versus those in the published report. If the protocol was not available, we compared outcomes listed in the Methods section of the included article versus those reported in the Results. If study authors reported results that were not statistically significant but did not provide data, we believe that bias was likely. We planned to contact study authors to obtain additional information, but the data may be unreliable (Chan 2004).

We assessed methods as:

adequate (when it was clear that all of the study’s prespecified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest for the review had been reported);

inadequate (when not all of the study’s prespecified outcomes were reported; when one or more reported primary outcomes were not prespecified; when outcomes of interest were reported incompletely and so could not be used; or when the study failed to include results of a key outcome that were expected to be reported); or

unclear (information was insufficient to permit judgement).

Other sources of bias

For each included study, we describe our important concerns about other possible sources of bias (e.g. whether a potential source of bias was related to the specific study design, whether the trial was stopped early because of some data‐dependent process). We also assessed whether each study was free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias and assigned risk as yes, no or unclear. If needed, we explored the impact of the level of bias by undertaking sensitivity analyses.

Data synthesis

If appropriate, we performed meta‐analyses of pooled data while assuming a fixed‐effect model. We used Review Manager 5.3 software for statistical analysis (RevMan 2014), and for estimates of typical risk ratio and risk difference, we used the Mantel‐Haenszel method. For measured quantities, we used the inverse variance method.

We performed two primary comparisons.

Glycerin prophylaxis versus placebo or no treatment.

Glycerin treatment versus placebo or no treatment.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned subgroup analysis a priori and planned to stratify data using the following variables: birth weight (< 1000 g and 1000 to 1500 g), gestational age at birth (< 28 weeks and 28 to 32 weeks), age at first treatment, intervention preparation (enemas or suppositories) and other possible sources of heterogeneity.

Sensitivity analysis

We could not perform sensitivity analysis because we identified a limited number of studies for inclusion in this review.

Results

Description of studies

See the Characteristics of included studies tables.

Prevention of feeding intolerance

Participants

Three included studies (Haiden 2007; Khadr 2011; Shinde 2014) reported outcomes for 177 infants. The study by Haiden 2007 included infants at < 32 weeks' gestation and < 1500 g; the study by Khadr 2011 included infants at > 24 weeks' gestation and < 32 weeks' gestation; and the study by Shinde 2014 included infants between 1000 and 1500 g with gestational age between 28 and 32 weeks. All studies excluded infants with major dysmorphic features and major congenital anomalies such as gastrointestinal (GI) disorders. The study by Khadr 2011 also excluded infants with hypoxic‐ischaemic encephalopathy (HIE) (stage > 2). The study by Shinde 2014 also excluded infants with haemodynamic instability and features of shock.

Interventions

Included studies randomly assigned infants to different preparations and dosages of glycerin. Haiden 2007 used glycerin enema, and Khadr 2011 and Shinde 2014 used glycerin suppository. The dose for glycerin in the study by Haiden 2007 was 10 mL/kg saline containing 0.8 g/10 mL glycerin; Khadr 2011 used a 250‐mg glycerin suppository once daily for infants born between 240/7and 276/7 weeks, and two 250‐mg glycerin suppositories (500 mg) once daily for infants born between 280/7and 31 weeks6/7; and Shinde 2014 used 1 g of glycerin suppository once a day from day 2 to day 14 of life. In the study by Haiden 2007, infants received glycerin enema if they did not spontaneously pass meconium during the first 12 hours of life. A second enema was administered if the infant had not passed meconium during the 24 hours following the first enema. This process was continued until complete evacuation of meconium was achieved. In the study by Khadr 2011, the intervention group received glycerin suppository once daily per rectum for 10 days, commencing at 24 hours of age.

Control

In all trials, the control group received no intervention.

Outcomes

The primary outcome for Haiden 2007 was time when the last meconium was passed; for Khadr 2011 and Shinde 2014, the primary outcome was time to full enteral feeds. Secondary outcomes included feeding tolerance for Haiden 2007, and NEC, sepsis, feeding intolerance, mortality, PDA, IVH, ROP and bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) for Khadr 2011. Shinde 2014 provided time required to regain birth weight, age when weight of 1700 g was achieved, NEC, proportion of infants for whom feeds were withheld for any reason and age at time of discharge from the hospital.

Treatment of feeding intolerance

We found no studies that utilized glycerin for treatment of feeding intolerance.

Results of the search

Our search on 2015 April 1 yielded three randomised trials that met our inclusion criteria for prevention of feeding intolerance (Haiden 2007; Khadr 2011; Shinde 2014).

Included studies

We included the following studies: Haiden 2007, Shinde 2014 and Khadr 2011.

Excluded studies

We excluded three studies: Marcos 2013 because investigators used saline enema and combined it with rectal stimulation in the same group; Shim 2007 as a result of the observational nature of the study; and Wang 2008 as the intervention was a combination of glycerin enema and Golden diplococci.

Risk of bias in included studies

See Risk of bias in included studies tables.

Allocation

All studies (Haiden 2007; Khadr 2011; Shinde 2014) were at low risk of bias for random sequence generation. We scored the study by Haiden 2007 as having unclear risk and the study by Khadr 2011 as having low risk of allocation concealment.

Blinding

Haiden 2007 and Khadr 2011 were at high risk of performance bias, as blinding was not performed. Given that both studies were not applicable for independent outcome assessment, we could not evaluate risk of detection bias. Shinde 2014 used a sham procedure.

Incomplete outcome data

All studies (Haiden 2007; Khadr 2011; Shinde 2014) were at low risk of attrition bias.

Selective reporting

All studies (Haiden 2007; Khadr 2011; Shinde 2014) were at low risk of reporting bias.

Other potential sources of bias

All studies (Haiden 2007; Khadr 2011; Shinde 2014) were at low risk of other potential sources of bias.

Effects of interventions

Glycerin prophylaxis versus placebo/no intervention (Comparison 1)

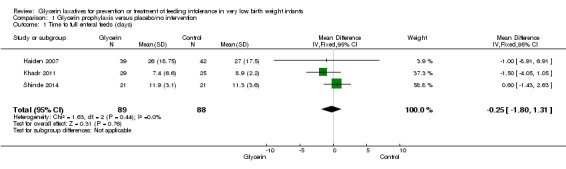

Time to full enteral feeds (days) (Outcome 1.1)

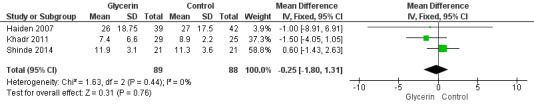

Figure 1: Three studies reported on this outcome (Khadr 2011; Haiden 2007; Shinde 2014). Investigators reported no statistically significant differences in time to full enteral feeds between the two groups (WMD ‐0.25, 95% CI ‐1.80 to 1.31; P value = 0.44).

1.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Glycerin prophylaxis versus placebo/no intervention, outcome: 1.1 Time to full enteral feeds (days).

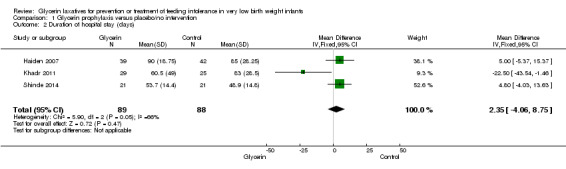

Duration of hospital stay (days) (Outcome 1.2)

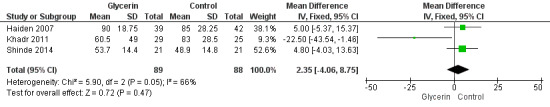

Figure 2: Three studies reported on this outcome (Khadr 2011; Haiden 2007; Shinde 2014). Researchers reported no statistically significant differences in duration of hospital stay between groups (WMD 2.35, 95% CI ‐4.06 to 8.75; P value = 0.05).

2.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Glycerin prophylaxis versus placebo/no intervention, outcome: 1.2 Duration of hospital stay (days).

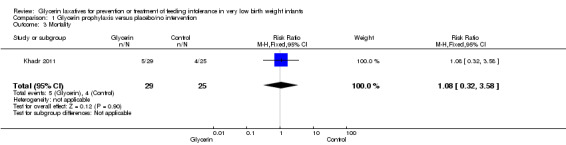

Mortality (Outcome 1.3)

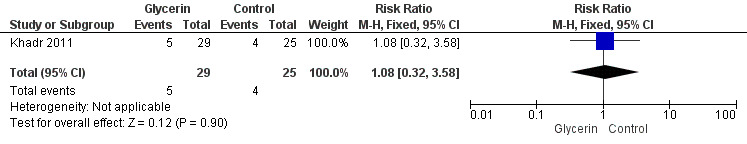

Figure 3: Only one study reported on this outcome (Khadr 2011) and described no statistically significant differences in mortality among study groups (RR 1.08, 95% CI 0.32 to 3.58; P value = 0.9).

3.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Glycerin prophylaxis versus placebo/no intervention, outcome: 1.3 Mortality.

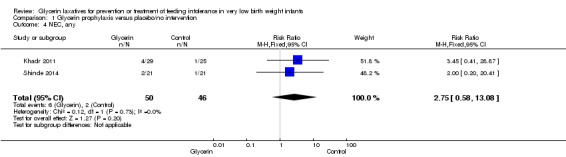

NEC (any stage) (Outcome 1.4)

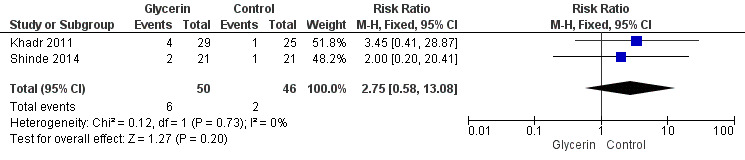

Figure 4: Only one study reported on this outcome (Khadr 2011) and described no statistically significant differences in NEC among study groups (RR 3.45, 95% CI 0.41 to 28.87; P value = 0.25).

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Glycerin prophylaxis versus placebo/no intervention, outcome: 1.4 Necrotising enterocolitis (NEC), any.

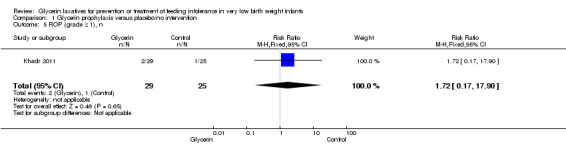

ROP (grade ≥1) (Outcome 1.5)

Only one study reported on this outcome (Khadr 2011) and described no statistically significant differences in ROP among study groups (RR 1.72, 95% CI 0.17 to 17.90; P value = 0.65).

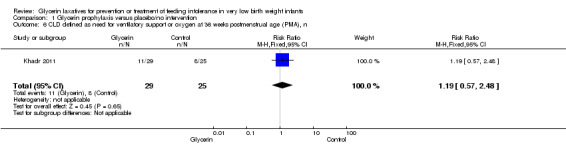

Chronic lung disease (CLD) defined as need for ventilatory support or oxygen at 36 weeks postmenstrual age (PMA) (Outcome 1.6)

Only one study reported on this outcome (Khadr 2011) and described no statistically significant differences in oxygen requirement at 36 weeks PMA among study groups (RR 1.19, 95% CI 0.57 to 2.48; P value = 0.65).

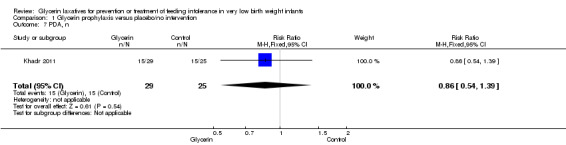

PDA (Outcome 1.7)

Only one study reported on this outcome (Khadr 2011) and described no statistically significant differences in PDA among study groups (RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.54 to 1.39; P value = 0.54).

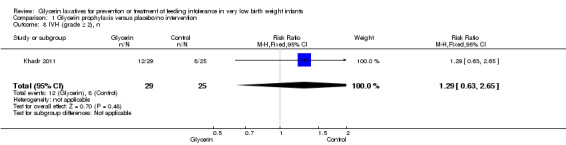

IVH (grade ≥2) (Outcome 1.8)

Only one study reported on this outcome (Khadr 2011) and described no statistically significant differences in IVH (grade ≥ 2) among study groups (RR 1.29, 95% CI 0.63 to 2.65; P value = 0.48).

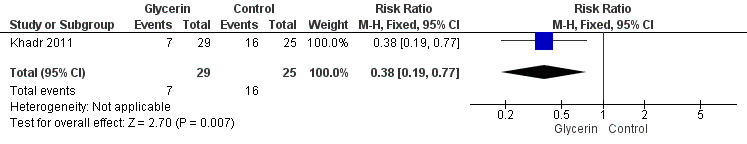

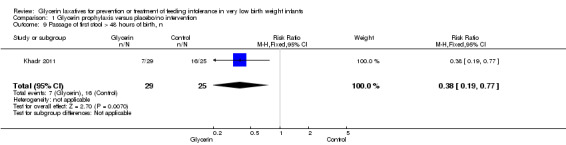

Passage of stool > 48 hours after birth (Outcome 1.9)

Figure 5: Only one study reported on this outcome (Khadr 2011). Investigators stated that administration of glycerin resulted in a significant improvement in stool passage over the first 48 hours in treated infants (RR 0.38, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.77; P value = 0.007).

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Glycerin prophylaxis versus placebo/no intervention, outcome: 1.9 Passage of first stool > 48 hours after birth, n.

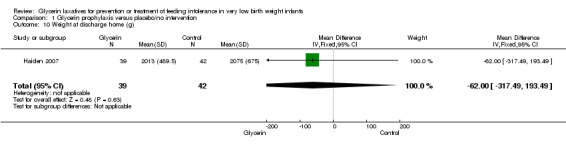

Weight at discharge home (g) (Outcome 1.10)

Only one study reported on this outcome (Haiden 2007) and described no statistically significant differences in weight at discharge home among study groups (MD ‐62.00, 95% CI ‐317.49 to 193.49; P value = 0.63).

Late‐onset sepsis (Outcome 1.11)

No included studies reported on this outcome.

Duration of total parenteral nutrition (TPN) (Outcome 1.12)

No included studies reported on this outcome.

Cholestasis at any time during hospital stay (Outcome 1.13)

No included studies reported on this outcome.

Adverse effects (Outcome 1.14)

No included studies reported side effects of treatment such as diarrhoea, rectal bleeding, dehydration or intestinal perforation.

Glycerin treatment versus placebo/no intervention (Comparison 2)

We found no studies eligible for this comparison.

Subgroup analysis

We could not perform subgroup analyses.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Our review summarises available evidence on efficacy and safety of glycerin laxatives for prevention or treatment of feeding intolerance in very low birth weight (VLBW) infants. We identified only three eligible trials that evaluated prophylactic use of glycerin laxatives and no eligible trials that evaluated therapeutic use of glycerin laxatives for feeding intolerance. We identified one ongoing study that is evaluating prophylactic use of glycerin suppositories for feeding intolerance and one that is assessing its therapeutic use for feeding intolerance; we will include them in future updates of this review. Our review showed that prophylactic administration of glycerin laxatives did not reduce time to full enteral feeds and did not influence other secondary outcomes, including duration of hospital stay, mortality, patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), intraventricular haemorrhage (IVH), necrotising enterocolitis (NEC), retinopathy of prematurity (ROP), bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) and weight at discharge home. Prophylactic administration of glycerin laxatives resulted in improved stool passage over the first 48 hours of life. Included trials reported no adverse effects.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The few included trials reported here did not allow us to address our objectives adequately. External validity of this review might be affected by differences in preparations and dosing regimens used and by variations in duration of the intervention under study. Along with passage of meconium, several factors can influence tolerance to feeds in the preterm host; therefore, healthcare providers may need to use a multi‐faceted approach when seeking to facilitate feeding tolerance.

Quality of the evidence

The validity of our review results is potentially compromised by the following: few studies addressing the topic of interest, limited sample size included in these studies (total of 177 infants from the three included studies) and use of different preparations and dosing regimens of the intervention under study (dose and duration of therapy may have been inadequate). Further, in Haiden 2007, protocol violations occurred in 23 participants (15 infants in the intervention group did not receive the enema, and eight in the control group did receive the enema). Study authors provided no explanation as to why protocol violations occurred, but they did state that additional infants were recruited to achieve the predetermined sample size. Even though study authors performed both intention‐to‐treat and per‐protocol analyses and reported no differences in outcomes, these events could have influenced outcomes. In Haiden 2007 and Khadr 2011, healthcare professionals and participants were not blinded, and this could have introduced bias.

Potential biases in the review process

This review utilised a very thorough and comprehensive search strategy. Review authors made every attempt to minimise the potential of publication bias. We included only randomised or quasi‐randomised controlled trials, and to minimise bias, review authors independently conducted all steps of this review.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Our review included three randomised controlled trials (Khadr 2011; Haiden 2007; Shinde 2014), in contrast to a recent review by Shah et al (Shah 2011), which included only one randomised controlled trial (Haiden 2007) and one observational study (Shim 2007). Our findings are consistent with those reported by Shah 2011: Evidence on prophylactic administration of glycerin laxatives to improve feeding intolerance in VLBW infants is inconclusive.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

We found insufficient evidence to support use of glycerin laxatives for prophylaxis or treatment of feeding intolerance in preterm infants.

Implications for research.

We recommend that additional studies should be performed to confirm or refute the effectiveness and safety of glycerin laxatives for feeding intolerance in VLBW infants.

Acknowledgements

None.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Glycerin prophylaxis versus placebo/no intervention.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Time to full enteral feeds (days) | 3 | 177 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.25 [‐1.80, 1.31] |

| 2 Duration of hospital stay (days) | 3 | 177 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.35 [‐4.06, 8.75] |

| 3 Mortality | 1 | 54 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.08 [0.32, 3.58] |

| 4 NEC, any | 2 | 96 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.75 [0.58, 13.08] |

| 5 ROP (grade ≥ 1), n | 1 | 54 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.72 [0.17, 17.90] |

| 6 CLD defined as need for ventilatory support or oxygen at 36 weeks postmenstrual age (PMA), n | 1 | 54 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.19 [0.57, 2.48] |

| 7 PDA, n | 1 | 54 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.86 [0.54, 1.39] |

| 8 IVH (grade ≥ 2), n | 1 | 54 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.29 [0.63, 2.65] |

| 9 Passage of first stool > 48 hours of birth, n | 1 | 54 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.38 [0.19, 0.77] |

| 10 Weight at discharge home (g) | 1 | 81 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐62.0 [‐317.49, 193.49] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Glycerin prophylaxis versus placebo/no intervention, Outcome 1 Time to full enteral feeds (days).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Glycerin prophylaxis versus placebo/no intervention, Outcome 2 Duration of hospital stay (days).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Glycerin prophylaxis versus placebo/no intervention, Outcome 3 Mortality.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Glycerin prophylaxis versus placebo/no intervention, Outcome 4 NEC, any.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Glycerin prophylaxis versus placebo/no intervention, Outcome 5 ROP (grade ≥ 1), n.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Glycerin prophylaxis versus placebo/no intervention, Outcome 6 CLD defined as need for ventilatory support or oxygen at 36 weeks postmenstrual age (PMA), n.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Glycerin prophylaxis versus placebo/no intervention, Outcome 7 PDA, n.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Glycerin prophylaxis versus placebo/no intervention, Outcome 8 IVH (grade ≥ 2), n.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Glycerin prophylaxis versus placebo/no intervention, Outcome 9 Passage of first stool > 48 hours of birth, n.

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Glycerin prophylaxis versus placebo/no intervention, Outcome 10 Weight at discharge home (g).

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Haiden 2007.

| Methods | Open randomised controlled trial | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: birth weight ≤ 1500 g and GA ≤ 32 weeks. Infants were further stratified according to GA (< 28 weeks or ≥ 28 weeks) Exclusion criteria: Infants with major congenital malformations and known gastrointestinal abnormalities |

|

| Interventions | Intervention group: Infants who failed to spontaneously pass meconium in the first 12 hours of life received a glycerin enema (10 mL/kg saline containing 0.8 g/10 mL glycerin). A urinary catheter (CH 8) lubricated with petrolatum was inserted into the rectum (2 cm in infants < 1000 g and 3 cm in infants weighing 1000 to 2000 g) to administer the enema. A second enema was administered if the infant failed to pass meconium during the 24 hours following the enema. This procedure was repeated until complete evacuation of meconium was achieved, defined as passage of 2 stools without macroscopic evidence of meconium within 24 hours Control group: No intervention was performed |

|

| Outcomes | Primary: time when the last meconium was passed Secondary: feeding tolerance |

|

| Notes | Austria | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Block randomly assigned |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Not blinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | |

| Other bias | Low risk | |

Khadr 2011.

| Methods | Open randomised controlled trial | |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria: inborn preterm infants between 240/7 and 316/7 weeks' gestation Exclusion criteria: infants with major dysmorphic features, structural gastrointestinal anomalies or hypoxic‐ischaemic encephalopathy > stage 2 |

|

| Interventions | Intervention group: Infants received a 250‐mg glycerin suppository once daily if born between 240/7 and 27 6/7 weeks, or two 250‐mg glycerin suppositories (500 mg) once daily if born between 280/7 and 316/7 weeks. Suppositories were administered daily for a total of 10 days, commencing at 24 hours of age Control group: Infants received no intervention |

|

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: time to full enteral feeds from commencement of enteral feeds (days) Secondary outcomes: NEC, sepsis, feeding intolerance, mortality, PDA, IVH, ROP, BPD |

|

| Notes | Study was conducted in Wishaw General Hospital, in Lanarkshire, UK ISRCTN47065764 Eudract_number: 2005‐000302‐31 |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | A set of study numbers and treatment allocation cards were generated by a research nurse at the beginning of the study. Each study number was paired with a treatment card, sealed in an opaque envelope and stratified by gestational age (240/7 to 27 6/7 and 280/7 to 316/7 weeks). The envelopes were then shuffled and stacked by gestational age before the study commenced |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Used consecutive sealed envelopes |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Not blinded |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | |

| Other bias | Low risk | |

Shinde 2014.

| Methods | Randomised controlled trial | |

| Participants | Setting: level III neonatal unit from Mumbai, India Participants: 50 very low birth weight (birth weight between 1000 and 1500 g) preterm (gestational age between 28 and 32 weeks) neonates randomly assigned to glycerin suppository (n = 25) or no intervention (n = 26) |

|

| Interventions | Glycerin suppository (1 g) once a day from day 2 to day 14 of life, or no suppository, along with intermittent oral feeds and standardised care | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: time required to achieve full enteral feeds (180 mL/kg/d) | |

| Notes | Results: Baseline characteristics of neonates such as gestational age, birth weight, gender and age at the time of introduction of feeds were comparable among groups. Mean (SD) duration to reach full enteral feed was 11.90 (3.1) days in the glycerin suppository group and was not significantly different (P value = 0.58) from mean duration in the control group (11.33 (3.57) days). The glycerin suppository group regained birth weight 2 days earlier than the control group, but this difference was not significant (P value = 0.16). Researchers reported no significant differences in duration of hospital stay or occurrence of necrotising enterocolitis among study groups Conclusions: Once‐daily application of glycerin suppository does not accelerate achievement of full feeds in preterm very low birth weight neonates |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | |

| Other bias | Low risk | |

Abbreviations: BPD = bronchopulmonary dysplasia. GA = gestational age. IVH = intraventricular haemorrhage. NEC = necrotizing enterocolitis. PDA = patent ductus arteriosus. ROP = retinopathy of prematurity.

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Marcos 2013 | Investigators studied saline enema and rectal stimulation in the same group |

| Shim 2007 | Observational study |

| Wang 2008 | Investigators studied glycerin enema and golden diplococci in the same group |

Characteristics of ongoing studies [ordered by study ID]

Almahmoud 2014.

| Trial name or title | Glycerin Suppositories for Treatment of Feeding Intolerance in Preterm Infants |

| Methods | Single‐centre randomised controlled clinical trial |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria

|

| Interventions | Glycerin group (GG) will receive the 0.5 suppository (700 mg) twice daily for 48 hours. We will use the rounded part and will discard the other part, then will hold the baby's buttocks for 2 minutes to ensure its delivery Rectal stimulation group (SG) will receive soft cotton swab inserted to around 3 cm. Stick will press against rectal wall in all directions for 2 minutes twice daily over 48 hours. Ky gel will be used to lubricate the stick while minimising direct friction to rectal wall Control group (CG) will receive routine neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) medical care with no specific intervention for the infant. Research nurse will use sham placebo twice daily by opening the diaper to blind the team for 2 minutes |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome

Secondary outcomes

|

| Starting date | 2014 |

| Contact information | Latifa Almahmoud latifa369@yahoo.com |

| Notes | NCT02149407 |

Khadawardi 2013.

| Trial name or title | Efficacy of Prophylactic Glycerin Suppositories for Feeding Intolerance in Very Low Birth Weight Preterm Infants: A Randomised Trial |

| Methods | Multi‐centre randomised controlled clinical trial |

| Participants | Inclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria

|

| Interventions |

|

| Outcomes | Primary outcome

Secondary outcomes

|

| Starting date | 2013 |

| Contact information | Emad Khadawardi |

| Notes | Saudi Arabia NCT01799629 |

Differences between protocol and review

None.

Contributions of authors

All review authors contributed to the idea and design of the research, to protocol development and to writing of this review. JA and VS searched the literature and extracted data. JA, AA and KA analysed the data. JA wrote the manuscript, which was reviewed by all review authors.

Sources of support

Internal sources

No sources of support supplied

External sources

-

Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, USA.

Editorial support of the Cochrane Neonatal Review Group has been funded with Federal funds from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, USA, under Contract No. HHSN275201100016C

Declarations of interest

None to declare.

New

References

References to studies included in this review

Haiden 2007 {published data only}

- Haiden N, Jilma B, Gerhold B, Klebermass K, Prusa A, Kuhle S, et al. Small volume enemas do not accelerate meconium evacuation in very low birth weight infants. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition 2007;44(2):270–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Khadr 2011 {published data only}

- Khadr S, Ibhanesebhor S, Rennix C, Fisher H, Manjunatha C, Young D, et al. Randomized controlled trial: impact of glycerin suppositories on time to full feeds in preterm infants. Neonatology 2011;100(2):169–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Shinde 2014 {published data only}

- Shinde S, Kabra NS, Sharma SR, Avasthi BS, Ahmed J. Glycerin suppository for promoting feeding tolerance in preterm very low birthweight neonates: a randomized controlled trial. Indian Pediatrics 2014;51(5):367‐70. [PUBMED: 24953576] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Marcos 2013 {published data only}

- Marcos M, Bueno M, Sanjose B, Gil M, Parada I, Amo P. Randomized controlled trial of prophylactic rectal stimulation and enemas on stooling patterns in extremely low birth weight infants. Journal of Perinatology 2013;33(11):858‐60. [PUBMED: 23907087] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Shim 2007 {published data only}

- Shim SY, Kim HS, Kim DH, Kim EK, Son DW, Kima B, et al. Induction of early meconium evacuation promotes feeding tolerance in very low birth weight infants. Neonatology 2007;92(1):67‐72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wang 2008 {published data only}

- Wang G, Li H, Huang Y, Huang C, Tan H. Effect of early intervention with glycerine enema and golden diplococci on feeding intolerance in very low birth weight infants. Journal of Applied Clinical Pediatrics 2008;14:1110‐1, 1135. [Google Scholar]

References to ongoing studies

Almahmoud 2014 {unpublished data only}

- Glycerin Suppositories for Treatment of Feeding Intolerance in Preterm Infants. Ongoing study 2014.

Khadawardi 2013 {unpublished data only}

- Efficacy of Prophylactic Glycerin Suppositories for Feeding Intolerance in Very Low Birth Weight Preterm Infants: A Randomised Trial. Ongoing study 2013.

Additional references

Bell 1978

- Bell MJ, Ternberg JL, Feigin RD, Keating JP, Marshall R, Barton L, et al. Neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. Therapeutic decisions based upon clinical staging. Annals of Surgery 1978;187(1):1‐7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

BNF 2010

- Paediatric Formulary Committee. BNF for Children 2010–2011. London: BMJ PublishingGroup, 2010. [Google Scholar]

Chan 2004

- Chan AW, Hróbjartsson A, Haahr MT, Gøtzsche PC, Altman DG. Empirical evidence for selective reporting of outcomes in randomized trials: comparison of protocols to published articles. JAMA 2004;291(20):2457‐65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gilman 1990

- Gilman AF, Rall WT, Nies AD, Taylor P. Goodman and Gilman's The Pharmacologic Basis of Therapeutics. New York: McGraw‐Hill Companies, 1990. [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2003

- Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta‐analyses. British Medical Journal 2003;327(7414):557–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2011

- Higgins JPT, Green S. The Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. www.cochrane‐handbook.org.

Hozo 2005

- Hozo SP, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Medical Research Methodology 2005;5:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

ICCROP 2005

- International Committee for the Classification of Retinopathy of Prematurity. The International Classification of Retinopathy of Prematurity revisited. Archives of Ophthalmology 2005;123(7):991‐9. [PUBMED: 16009843] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jadcherla 2002

- Jadcherla SR, Kliegman RM. Studies of feeding intolerance in very low birth weight infants: definition and significance. Pediatrics 2002;109(3):516‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kaufman 2003

- Kaufman SS, Gondolesi GE, Fishbein TM. Parenteral nutrition associated liver disease. Seminars in Neonatology 2003;8(5):375–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mansi 2011

- Mansi Y, Abdelaziz N, Ezzeldin Z, Ibrahim R. Randomized controlled trial of a high dose of oral erythromycin for the treatment of feeding intolerance in preterm infants. Neonatology 2011;100(3):290‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Meetze 1993

- Meetze WH, Palazzolo VL, Bowling D, Behnke M, Burchfield DJ, Neu J. Meconium passage in very low birth weight infants. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition 1993;17(6):537–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moore 2011

- Moore TA, Wilson ME. Feeding intolerance: a concept analysis. Advances in Neonatal Care 2011;11:149–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Newell 2000

- Newell SJ. Enteral feeding of the micropremie. Clinics in Perinatology 2000;27(1):221–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Papile 1978

- Papile LA, Burstein J, Burstein R, Koffler H. Incidence and evolution of subependymal and intraventricular hemorrhage: a study of infants with birth weights less than 1,500 gm. Journal of Pediatrics 1978;92(4):529‐34. [PUBMED: 305471] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Patole 2005

- Patole S. Strategies for prevention of feed intolerance in preterm neonates: a systematic review. Journal of Maternal‐Fetal and Neonatal Medicine 2005;18(1):67‐76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

RevMan 2014 [Computer program]

- The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager (RevMan). Version 5.3. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014.

Ringer 1996

- Ringer SA, Nurko S, Fournier K, Stark AR. Feeding intolerance in infants 24 to 29 weeks gestation: incidence and presentation. Pediatric Research 1996;39:319. [Google Scholar]

Shah 2011

- Shah V, Chirinian N, Lee S, EPIQ Evidence Review Group. Does the use of glycerin laxatives decrease feeding intolerance in preterm infants?. Paediatrics & Child Health 2011;16(9):e68‐70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Stoll 2002

- Stoll BJ, Hansen N, Fanaroff AA, Wright LL, Carlo WA, Ehrenkranz RA, et al. Late‐onset sepsis in very low birth weight neonates: the experience of the NICHD Neonatal Research Network. Pediatrics 2002;110(2 Pt 1):285‐91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Stoll 2004

- Stoll BJ, Hansen N, Adams‐Chapman I, Fanaroff AA, Hintz SR, Vohr BR, et al. Neurodevelopmental and growth impairment among extremely low birth‐weight infants with neonatal infection. Journal of the American Medicine Association 2004;292(19):2357‐65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Unger 1986

- Unger A, Goetzman BW, Chan C, Lyons AB 3rd, Miller MF. Nutritional practices and outcome of extremely premature infants. American Journal of Diseases of Children 1986;140(10):1027‐33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wang 1994

- Wang PA, Huang FY. Time of the first defecation and urination in very low birth weight infants. European Journal of Pediatrics 1994;153(4):279–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Weaver 1993

- Weaver LT, Lucas A. Development of bowel habit in preterm infants. Archives of Disease in Childhood 1993;68(3):317–20. [PUBMED: 8466270] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Zenk 1993

- Zenk KE, Koeppel RM, Liem LA. Comparative efficacy of glycerin enemas and suppository chips in neonates. Clinical Pharmacy 1993;12(11):846–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]