Abstract

Background:

Serum Chromogranin A (CgA) is widely used as a biomarker for pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PanNETs). The aim of this study was to investigate the value of CgA as a diagnostic and prognostic marker for well-differentiated PanNETs.

Methods:

Patients with well-differentiated PanNET and a baseline CgA measurement, between 2011 and 2016 were reviewed. The diagnostic value was determined by comparing CgA values from patients with PanNETs to those with other pancreatic neoplasms and healthy controls. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to investigate the CgA prognostic significance.

Results:

Ninety-nine patients met inclusion criteria. As a diagnostic marker, CgA had a sensitivity of 66%, specificity of 95%, and overall accuracy of 71%. The use of PPIs was associated with a higher CgA level (p=0.015). When excluding patients on PPIs, CgA accuracy in distinguishing PanNETs from other pancreatic neoplasms was 66%, the sensitivity and specificity were 60% and 75% respectively. Elevated CgA (p=0.004), Ki67% (p<0.001), tumor grade (p<0.001) and stage of disease (p=0.036) were associated with disease-specific survival.

Conclusion:

CgA has a limited role as a diagnostic biomarker for well-differentiated PanNETs. An elevated CgA level may have prognostic value but its role should be further investigated with respect to other known pathological factors.

Introduction

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PanNETs) are the second most frequent neoplasm of the pancreas with an annual incidence rate of 0.8 per 100,000 people(1). The majority of these tumors are well-differentiated, but only a small proportion release active hormones that result in a specific clinical syndrome. Most PanNETs (75–80%) are thus non-functioning tumors, and are usually detected at an advanced stage (2–5). In recent years, small non-functional PanNETs have been increasingly diagnosed due to the widespread use of high-resolution cross-sectional imaging(1,6). Most of these small tumors are low-grade neoplasms and are increasingly being managed with radiological surveillance protocols rather than surgical resection(6). Even these small non-functioning lesions are presumed to have metastatic potential,and therefore a non-invasive tumor marker would be clinically relevant for both diagnosis and prognosis.

Chromogranin A (CgA) is the most commonly measured circulating biomarker for the diagnosis and follow up of PanNETs (7,8). CgA is a glycoprotein that belongs to the chromogranin family. The protein is stored in the secretory granules of normal neuroendocrine cells and it can be measured in serum or plasma (5,9,10). Several studies have suggested CgA is a reliable diagnostic biomarker for PanNETs, and that its value may correlate with tumor grade, stage of disease and the overall liver metastatic burden(10–13). A few reports have also suggested that CgA may be useful as a prognostic marker for both progression-free and overall survival, and a useful clinical tool in monitoring therapeutic response (10,11,14–16). However, emerging data have raised concerns about the clinical relevance of CgA, curbing the enthusiasm for its use as a biomarker. The major limitation of CgA is its lack of specificity as it is elevated in other medical conditions such as renal failure, non-neuroendocrine neoplasms, and in patients taking proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs)(12,17). In addition, CgA can be normal in small and localized PanNETs, non-functioning tumors, insulinomas, and in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN-1) (18–23). Finally, interpreting CgA values can be challenging due to the lack of standardization among available assays and measurements across different laboratories.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the performance characteristics of serum CgA assessed by a single assay as a diagnostic and prognostic biomarker for PanNETs. Recently, a study from Memorial Sloan Kettering demonstrated that well-differentiated PanNETs consist of a wide spectrum of neoplasms that include both low-grade and high-grade tumors. In particular, those with a proliferative index >20%, have different clinical and radiographic features and a distinct prognosis and response to treatment from poorly-differentiated neoplasms(24). To avoid therefore biases caused by the differences in the underlying tumor biology, we reviewed retrospectively our cases and included only patients with well-differentiated tumors. We evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of CgA comparing patients affected by well-differentiated PanNET with a pool of healthy volunteers and with patients affected by other pancreatic neoplasms. In addition, we investigated the prognostic value of CgA baseline measurement for prediction of disease-specific survival (DSS).

Methods

Study Population and data collection

The study protocol was approved by the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK) Institutional Review Board. The MSK pancreatic database was then queried for patients who had a serum CgA measurement between 2011 and 2016. We limited the study to this period since MSK employed an electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (ECLIA) before 2011and subsequently has adopted an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Nowadays, the ECLIA is no longer available on the market, so it was not possible to use ECLIA on our healthy population and evaluate its diagnostic value.We retrospectively reviewed clinical, radiological and pathological reports of all patients selected for the study. Patients were included if they had a baseline CgA measurement and a diagnosis of well-differentiated PanNET defined by pathology report. Patients with a diagnosis of poorly-differentiated PanNET were excluded. To evaluate the diagnostic performance of serum CgA, we recruited a cohort of 21 healthy controls. All healthy participants gave written consent for validation studies. The healthy controls were eligible blood donors with normal liver biochemistry and renal function with no malignant disease. Finally, we retrospectively collected data of 48 patients with pancreatic lesions other than PanNET (pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PDAC) n=36, acinar cell carcinoma (ACC) n=2, solid pseudo-papillary neoplasm (SPN) n=3, metastatic renal clear cell carcinoma (mRCC) n=2, serous cystadenoma n=3, pancreatic sarcoma (PS) n=1, anaplastic carcinoma (AC) n=1) who had undergone CgA serum measurement during the same time period and who were not taking PPIs.

Serum CgA was measured by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) with a normal range ≤15 ng/ml performed by a commercial kit (Quest Diagnostics, San Juan Capistrano, CA, USA). Elevated baseline CgA serum level was defined as any value greater than the upper limit of normal (ULN) per the ELISA (>15 ng/ml) assays.

PanNETs were classified and graded according to the 2010 World Health Organization (WHO) classification of the exocrine and endocrine neoplasms of the pancreas(25). Tumor stage was defined according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) definitions(26). Patient followed-up duration was calculated from the date of the first counseling at MSK until the date of death or date of last known follow-up.

Statistical Analysis

The Receiver-operating characteristics (ROC) curve and the area under the curve (AUC) were calculated to define the ability of serum CgA to discriminate between PanNETs and healthy controls and other pancreatic neoplastic diseases. The optimal cut-off was defined as the point on the ROC curve which corresponds to the Youden index. Continuous variables were reported as median and interquartile range (IQR), while categorical variables were presented as absolute numbers and percentages. Comparative analysis between groups was conducted using χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables and Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitneycontinuous variables. Associations between patient’s characteristics and CgA>ULN were assessed by univariate analysis and multivariate logistic regression analysis. The univariate survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan-Meier method for categorical variables and by Cox proportional hazards regression model for continuous variables model. Significance level (p) <0.05 was considered statistically significant in a two-tailed analysis. Statistical analysis was performed using the IBM SPSS v.25 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) software package and GraphPad Prism 7.01 (Graph-Pad Software Inc) was used to generate graphs.

Results

Patient characteristics

During the study period, there were 99 patients identified with pathologic diagnosis of PanNET and a baseline CgA measurement. The median age at diagnosis was 59 years (IQR 16) and 55 were male. The tumors were functioning in 7 cases and among those, 3 were insulinomas, 3 gastrinomas and 1 was a vipoma. Overall, 7 patients had MEN 1 syndrome and developed PanNETs. Stage I disease was present in 23 patients, 8 patients had stage II disease, 6 patients had stage III disease, and 62 patients had stage IV disease. Overall, 34 patients were taking PPIs at the time of CgA measurement. None of the 99 patients had a significantly increased serum creatinine value; the maximum creatinine value observed was 1.7 mg/dl (creatinine clearance 1.2 mg/dl) and the median value for the entire cohort was 0.8 mg/dl (IQR 0.2).

Diagnostic Value

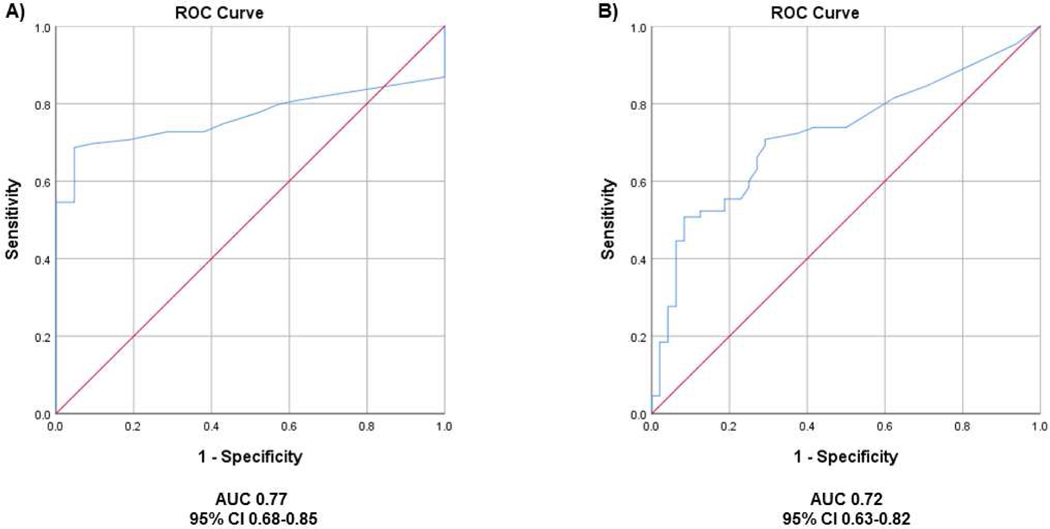

The ROC curve obtained for all patients with a diagnosis of PanNET (n=99) and the healthy controls (n=21) (Figure 1A) had an AUC of 0.77. The Youden index demonstrated an optimal cut-off of 14 ng/ml to discriminate between patients with PanNETs and healthy controls. However, because this result was consistent with the cut-off of 15 ng/ml provided by the commercial kit, we decided to use this value for further analysis. We found that the referral range of 15 ng/ml had a sensitivity of 66%, a 95% specificity, an overall accuracy of 71%. Treatment with PPIs was associated with an elevated CgA level (median 60 ng/ml IQR 204 vs. 44 ng/ml IQR 149, p=0.015), and the exclusion of these patients (n=34) from the analysis led to a reduction of referral range sensitivity to 60% and of diagnostic accuracy to 68%, with an AUC of 0.71. No variations in specificity were observed.

Figure 1.

Chromogranin A diagnostic value. (A) ROC curve obtained with 99 patients with PanNET and 21 healthy controls. (B) ROC obtained with 65 patients with PanNET not taking PPI and 48 patients with non-neuroendocrine pancreatic neoplasms

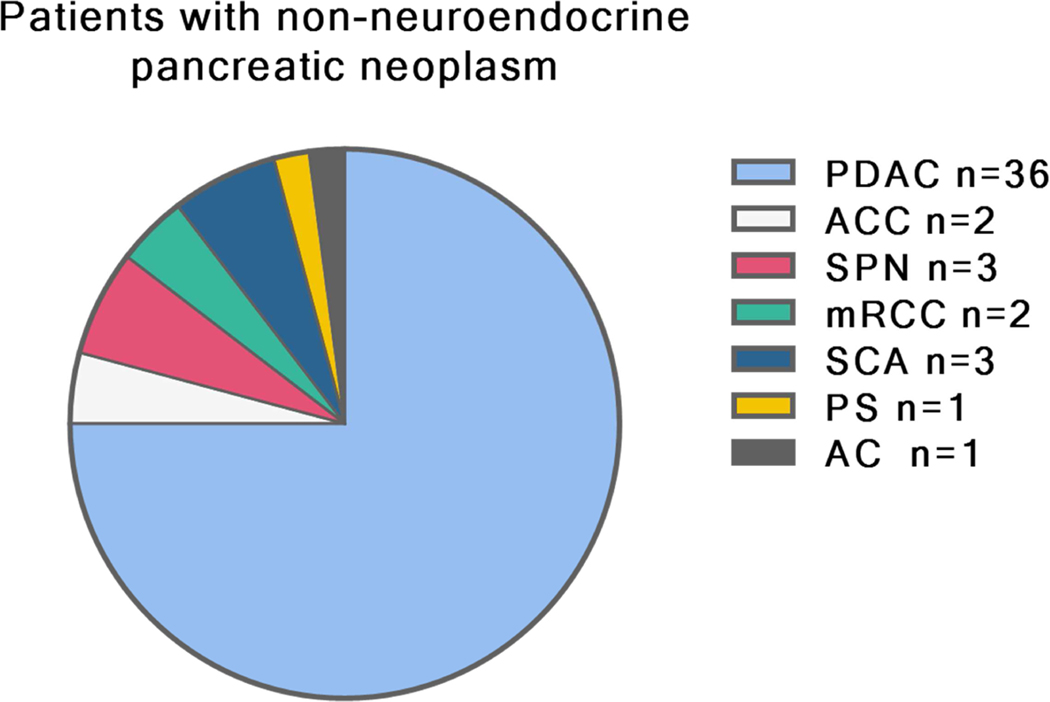

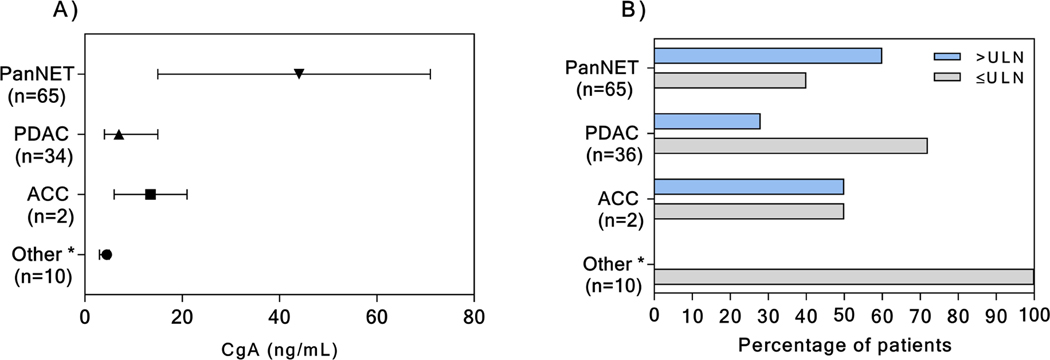

We next investigated the ability of serum CgA in discriminating between PanNETs (not taking PPIs) and other pancreatic lesions (Figure 2). In this instance, when compared to patients with other pancreatic neoplasms, the CgA specificity, the sensitivity, and the diagnostic accuracy, at the referral range were further reduced to 75%, 60%, and 66% respectively, with an AUC of 0.72 (Figure 1B). Serum CgA level was elevated in 10/36 patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PDAC), and in 1 patient with acinar cell carcinoma (ACC) (Figure 3). Details on the pathology of the other pancreatic neoplasms are shown in Figure 2. In none of these other cases, was the serum CgA value increased (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Pathological diagnosis ofpatients with non-neuroendocrine pancreatic tumors.

*PDAC=pancreatic adenocarcinoma, ACC=acinar cella carcinoma, SPN=solid pseudo-papillary neoplasm, mRCC=metastatic renal clear cell carcinoma, SCA=serous cysticadenoma, PS=pancreatic sarcoma, AC=anaplastic carcinoma

Figure 3.

Median with 95% CI CgA serum value in patients with PanNET and with non-PanNET pancreatic tumors (A). Percentage of patients with CgA serum value upper the limit of normal (ULN) according to pathology (B).

*Other neoplasm includes: solid pseudo-papillary neoplasm (n=3), metastatic renal clear cell carcinoma (n=2), serous cystadenoma (n=3), pancreatic sarcoma (n=1), anaplastic carcinoma (n=1)

Serum CgA levels and clinical and pathological characteristics of patients

To investigate the relationship between CgA values and PanNETs clinical and pathological features, we excluded patients taking PPIs (n=34) removing the bias due to their influence on CgA levels. All cases of PanNETs arising in the context of a MEN-1 syndrome were associated with normal CgA levels (Table 1), whereas those thought to be sporadic PanNETs had an increased CgA in 39/60 cases. According to the WHO tumor grading, an increased CgA was identified in 7/19 of grade 1 (G1) cases, 22/35 of patients with grade 2 (G2) PanNETs, and 6/6 of patients with grade 3 (G3) lesions. With respect to disease stage, serum CgA was increased in 6/27 of patients with a localized disease (stage I-III) and in 33/38 of patients with stage IV disease. Median CgA value according to clinical and pathological features are shown on Table 2. Multivariate analysis found a CgA> ULN to be independently associated with stage IV disease only (OR=31, 95% CI 7 to 129, p<0.001).

Table 1.

Association of CgA pre-treatment value with clinical and pathological characteristics of 65 patients with diagnosis of PanNET not taking PPIs. ULN indicates upper limit of normal.

| CgA value | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | ≤ULN n=26 | >ULN n=39 | p |

| Male, n (%) | 16 (62) | 21 (54) | 0.614 |

| Age, mean (SD) | 52 (15) | 60 (15) | 0.017 |

| Functional, n (%) | 1.000 | ||

| Yes, | 1 (4) | 2 (5) | |

| No, | 25 (96) | 37 (95) | |

| Hereditary Syndrome, n (%) | 0.008 | ||

| Yes | 5 (19) | 0 (0) | |

| No | 21 (81) | 39 (100) | |

| Primitive Site, n (%) | 0.092 | ||

| Head | 13 (50) | 11 (28) | |

| Body | 7 (27) | 9 (23) | |

| Tail | 6 (23) | 19 (49) | |

| Primitive Tumor Size, median (IQR), cm | 3.0 (4) | 3.4 (3) | 0.142 |

| OctreoScan*, n (%) | 0.057 | ||

| Positive | 6 (67) | 31 (94) | |

| Negative | 3 (33) | 2 (6) | |

| Ki67 %**, median (IQR) | 4 (6) | 8 (14) | 0.072 |

| Grade***, n (%) | 0.017 | ||

| G1 | 12 (48) | 7 (20) | |

| G2 | 13 (52) | 22 (63) | |

| G3 | 0 (0) | 6 (17) | |

| AJCC Stage, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| I | 16 (62) | 2 (5) | |

| II | 3 (11) | 3 (8) | |

| III | 2 (8) | 1 (2) | |

| IV | 5 (19) | 33 (85) | |

Octreoscan performed on 42/65 patients,

Available for 50/65 patients,

Available for 60/65 patients

Table 2.

CgA values according to clinical and pathological characteristics of 65 patients with diagnosis of PanNET not taking PPIs.

| Variables | CgA value, ng/ml median (IQR) | p |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.715 | |

| Male | 110 (19–225) | |

| Female | 105 (40–369) | |

| Functional | 0.731 | |

| Yes | 62 (3-NA) | |

| No | 38 (5–149) | |

| Hereditary Syndrome | 0.009 | |

| Yes | 5 (3–7) | |

| No | 45 (9–173) | |

| Primitive Tumor Size | 0.007 | |

| ≤2 cm | 9 (3–50) | |

| >2cm | 57 (11–200) | |

| OctreoScan* | 0.038 | |

| Positive | 108 (29–250) | |

| Negative | 4 (3–122) | |

| Grade*** | 0.006 | |

| G1 | 9 (3–108) | |

| G2 | 44 (8–122) | |

| G3 | 215 (141–1425) | |

| AJCC Stage | <0.001 | |

| I | 5 (3–10) | |

| II | 18 (11–80) | |

| III | 4 (3-NA) | |

| IV | 108 (44–240) |

Octreoscan performed on 42/65 patients,

Available for 50/65 patients,

Available for 60/65 patients

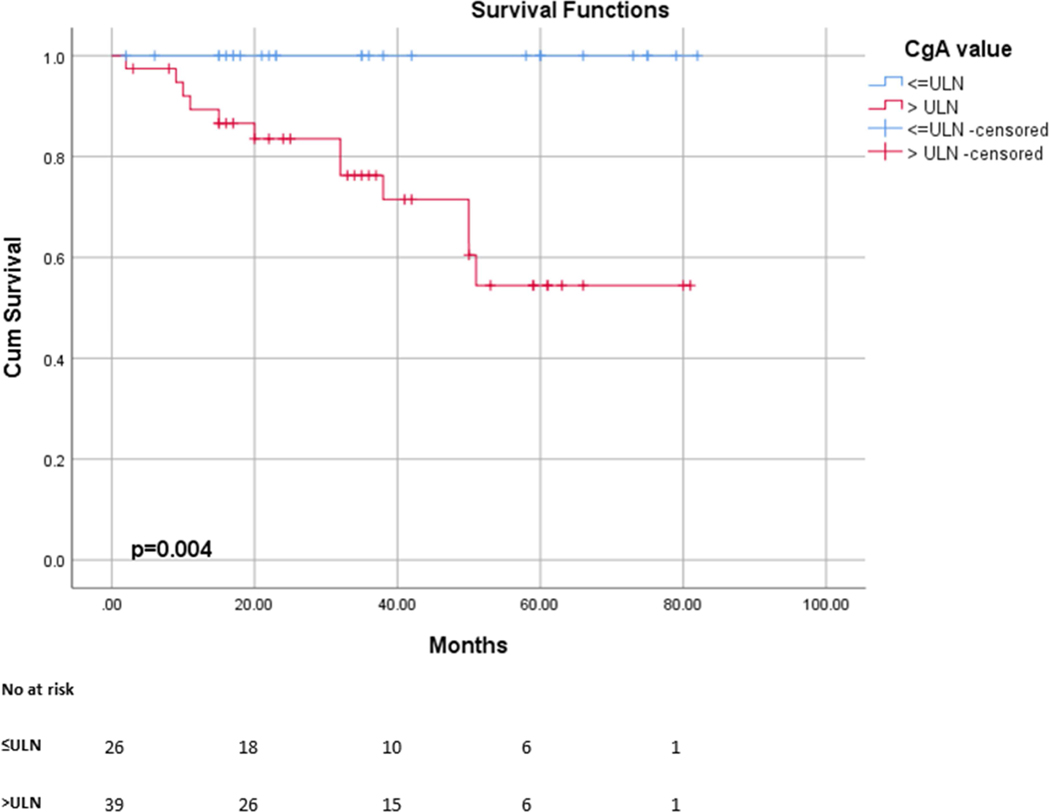

Prognostic value of disease-specific survival

Survival analysis was performed for the 65 patients with PanNET who were not taking PPIs at the time of CgA measurement. The median follow-up time was 35 months (IQR 42), and during the study period, 21 patients died of disease. According to the survival analysis, patients with a CgA>ULN had a significantly poorer survival than those with CgA within the referral range (3 years DSS 100% Vs 76%; OR=5.54, 95% CI 1.74 to 17.69, p=0.004) (Figure 4). Other predictors of shorter disease-specific survival were the WHO classification (G3, OR 6.79, 95% CI 2.66 to 17.35, P<0.001), Ki67% (OR 1.04, 95% 1.02 to 1.06, P<0.001) and AJCC stage of disease (Stage IV, OR 47.7, 95% CI 1.28 to 1781, p=0.036).

Figure 4.

Disease specific survival curve of patients based on CgA levels. Patients with high CgA level (>15 ng/ml) had a significantly poorer survival than patients with low CgA levels (≤15 ng/ml)

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the diagnostic and prognostic value of serum CgA in patients with well-differentiated pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. The results of this study suggest that serum CgA functions poorly as a diagnostic marker due to a low sensitivity. A recent expert consensus statement on neuroendocrine tumors reported that an optimal circulating biomarker should exhibit performance metrics that have a sensitivity higher than 80% and a specificity higher than 90%(17). In this study, we observed a 95% specificity of circulating CgA in discriminating PanNETs from healthy controls. However, this was not true when serum CgA levels were compared between patients with pancreatic neoplasms that were not endocrine tumors. Because several common medical conditions (renal failure, treatment with PPIs, and non-endocrine pancreatic neoplasia) may increase CgA levels, and because these conditions were not adequately controlled for in the present study, we feel that the upper limit of specificity of 95% is likely an overestimate (5,27–29).

The use of PPIs is known to be associated with elevated serum CgA levels which may persist for up to two weeks after the discontinuation of the medical therapy(5,30,31). PPIs decrease the gastric acidity, leading to an enhanced release of gastrin that promotes the hyperplasia of enterochromaffin-like cells and their synthesis of CgA, resulting in increased CgA serum levels(32,33). In our series, patients with PanNET taking PPIs had significantly increased levels of CgA compared to those that were not under PPI treatment, and their exclusion from the analysis led to a reduction in the sensitivity to 60%. However, none of the healthy controls were taking PPIs, and it was therefore not possible to investigate false positive rates due to PPI treatment. CgA specificity was assessed when PanNETs were compared to other pancreatic neoplasms. Abnormal CgA levels were present in about one-third of patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma, and in one patient with acinar cell carcinoma, reducing the test specificity from 95% to 75%. A recent study(19) that investigated the specificity of CgA in identifying PanNETs from other pancreatic tumors reported similar results showing comparable CgA levels among patients with PDAC and with PanNETs. However, our results did find a high positive predictive value of CgA in discriminating PanNETs from pancreatic neoplasms as solid pseudopapillary neoplasm, renal clear cell carcinoma metastasis, and non-neuroendocrine cystic neoplasia (Figure 3).

The primary concern regarding the use of serum CgA as a diagnostic test is its low sensitivity. The sensitivity reported in the literature ranges broadly between 27% and 63% according to the stage of disease, grade of differentiation, and the presence of a functional and/or hereditary syndrome(10,12,13,15). Previous studies(10,12,34) have suggested that high CgA levels may be associated with the presence of metastasis and the burden of liver disease. Surgical series suggest that the sensitivity of CgA is reduced when PanNETs are localized, with sensitivities ranging from 27–49% (15,18,19). Elevated CgA levels have been reported to be associated not only with the stage of disease, but also with increasing size of the primary tumor (15,19), and tumor grade (15). In this study, CgA failed as diagnostic biomarker in 40% of PanNETs. Increased serum CgA levels were present in less than a quarter of patients with stage I-III disease, whereas elevated CgA was an independent predictor of the presence of metastasis. Almost two-thirds of patients with G1 PanNETs had CgA levels within normal range, and tumors smaller than 2 cm had significantly lower CgA values than larger neoplasm, supporting the concern over the CgA role as biomarker for both early diagnosis and follow-up of small low-grade neoplasms enrolled in surveillance protocols. However, in this series 63% of G2 tumors and 100% G3 tumors presented with a baseline serum CgA value above the limit of normal, suggesting that CgA might have a role in detection and monitoring progression in these cases. Interestingly, in our series, none of the patients with MEN-1 syndrome had increased CgA values, further demonstrating its limitation in this setting. Although our numbers are too small to make any definitive conclusion, similar results have been reported in larger cohorts. In studies focusing on MEN-1 syndrome, CgA showed an AUC of only 0.48–0.59 for diagnosis of PanNET(35,36). This observation probably reflects the fact that PanNET in MEN-1 syndrome are more often of a lower grade, smaller and localized than in sporadic PanNET. As we showed in this study, patients having PanNET with these characteristics usually have CgA serum value within normal limits. Therefore, better and more reliable biomarkers other than CgA would be needed for early detection of neuroendocrine neoplasms and lifelong follow up in MEN-1 patients. (37).

Finally, we evaluated the prognostic value of an elevated baseline CgA. Currently, there is no consensus regarding CgA as a prognostic biomarker in well-differentiated PanNETs (17,38). A small study by Han et al. (10) included 43 metastatic well-differentiated PanNETs and observed that a baseline CgA>2.5 ULN was a predictor of overall survival. In addition, Shanahan et al(15) described a 5-year overall survival of 67% in patients with an elevated CgA compared to 100% 5-year survival in those with a normal value. Our data confirmed this trend, showing a significantly reduced DSS in patients with baseline elevated CgA. However, all of these series, including the present study, are retrospective and based on a limited number of patients, and on a small number of events, preventing a more in-depth analysis adjusted for possible confounders, such as the tumor grade and stage of the disease.

There are several limitations to this study. First, the retrospective nature of the study prevents us from exploring the dynamic variations of CgA during follow-up. Second, we were unable to compare different assays for CgA measurement. The accuracy of CgA has been reported to be associated with the assay employed, and different results are to be expected using different assays. Third, although our results suggest that elevated CgA has prognostic value, we cannot rule out the possibility of selection bias in that clinicians may be drawing CgA levels in patients with more advanced and worrisome disease (i.e. particularly in patients with advanced disease involving the bone which is harder to assess radiographically). Finally, our control population was truly “healthy”, and lacked some of the conditions that may confound the accuracy of CgA such as renal failure and PPI use. If these conditions had been present in the controls, then we would have expected our results to show an even further decrease in sensitivity and specificity.

In conclusion, the results of this retrospective study suggest that CgA has a limited role as a diagnostic biomarker for well-differentiated PanNET, especially in patients with localized disease. Our results show an elevated CgA level may have prognostic value with respect to disease-specific survival. However, this prognostic role should be further investigated in larger series with a longer follow-up and with respect to other pathological factors as the grade and the stage of the disease.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Dasari A, Shen C, Halperin D, Zhao B, Zhou S, Xu Y, et al. Trends in the Incidence, Prevalence, and Survival Outcomes in Patients With Neuroendocrine Tumors in the United States. JAMA Oncol. 2017;26(13):2124–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crippa S, Partelli S, Zamboni G, Scarpa A, Tamburrino D, Bassi C, et al. Incidental diagnosis as prognostic factor in different tumor stages of nonfunctioning pancreatic endocrine tumors. Surg (United States). 2014;155(1):145–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyar Cetinkaya R, Vatn M, Aabakken L, Bergestuen DS, Thiis-Evensen E. Survival and prognostic factors in well-differentiated pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2014;49(6):734–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zerbi A, Falconi M, Rindi G, Fave GD, Tomassetti P, Pasquali C, et al. Clinicopathological Features of Pancreatic Endocrine Tumors: A Prospective Multicenter Study in Italy of 297 Sporadic Cases. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(6):1421–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Modlin IM, Gustafsson BI, Moss SF, Pavel M, Tsolakis A V, Kidd M. Chromogranin A— Biological Function and Clinical Utility in Neuro Endocrine Tumor Disease. Annl Surg Oncol. 2010;17:2427–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sadot E, Reidy-Lagunes DL, Tang LH, Do RK, Gonen M, D’Angelica MI, et al. Observation versus Resection for Small Asymptomatic Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors: A Matched Case-Control Study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23(4):1361–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Falconi M, Eriksson B, Kaltsas G, Bartsch DK, Capdevila J, Caplin M, et al. ENETS Consensus Guidelines Update for the Management of Patients with Functional Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors and Non-Functional Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Neuroendocrinology. 2016. January 5;103(2):153–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kulke MH, Anthony LB, Bushnell ÞDL, Herder WW De, Goldsmith SJ, Klimstra DS, et al. NANETS G UIDELINES NANETS Treatment Guidelines of the Stomach and Pancreas. Pancreas. 2010;39(6):735–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cimitan M, Buonadonna A, Cannizzaro R, Canzonieri V, Borsatti E, Ruffo R, et al. Somatostatin receptor scintigraphy versus chromogranin A assay in the management of patients with neuroendocrine tumors of different types: Clinical role. Ann Oncol. 2003;14(7):1135–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Han X, Zhang C, Tang M, Xu X, Liu L, Ji Y, et al. The value of serum chromogranin A as a predictor of tumor burden, therapeutic response, and nomogram-based survival in well-moderate nonfunctional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors with liver metastases. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015. May;27(5):527–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Massironi S, Rossi RE, Casazza G, Conte D, Ciafardini C, Galeazzi M, et al. Chromogranin a in diagnosing and monitoring patients with gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms: A large series from a single institution. Neuroendocrinology. 2014;100:240–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hijioka M, Ito T, Igarashi H, Fujimori N, Lee L, Nakamura T, et al. Serum chromogranin A is a useful marker for Japanese patients with pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Cancer Sci. 2014;105(11):1464–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paik WH, Ryu JK, Song BJ, Kim J, Park JK, Kim YT, et al. Clinical usefulness of plasma chromogranin a in pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasm. J Korean Med Sci. 2013;28(5):750–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yao JC, Pavel M, Phan AT, Kulke MH, Hoosen S, St Peter J, et al. Chromogranin A and neuron-specific enolase as prognostic markers in patients with advanced pNET treated with everolimus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(12):3741–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shanahan MA, Salem A, Fisher A, Cho CS, Leverson G, Winslow ER, et al. Chromogranin A predicts survival for resected pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. J Surg Res. 2016;201(1):38–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rossi RE, Garcia-Hernandez J, Meyer T, Thirlwell C, Watkins J, Martin NG, et al. Chromogranin A as a predictor of radiological disease progression in neuroendocrine tumours. Ann Transl Med. 2015;3(9):118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oberg K, Modlin IM, De Herder W, Pavel M, Klimstra D, Frilling A, et al. Consensus on biomarkers for neuroendocrine tumour disease. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(9):e435–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jilesen APJ, Busch ORC, Van Gulik TM, Gouma DJ, Nieveen Van Dijkum EJM. Standard pre- and postoperative determination of chromogranin a in resectable non-functioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors - Diagnostic accuracy: NF-pNET and low tumor burden. Dig Surg. 2014;31(6):407–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jun E, Kim SC, Song KB, Hwang DW, Lee JH, Shin SH, et al. Diagnostic value of chromogranin A in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors depends on tumor size: A prospective observational study from a single institute. Surgery. 2017. July;162(1):120–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mirkin KA, Hollenbeak CS, Wong J. Impact of chromogranin A, differentiation, and mitoses in nonfunctional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors ≤2 cm. J Surg Res. 2017;211(717):206–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheng Y, Sun Z, Bai C, Yan X, Qin R, Meng C, et al. Serum chromogranin A levels for the diagnosis and follow-up of well-differentiated non-functioning neuroendocrine tumors. Tumor Biol. 2016;37(3):2863–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qiao XW, Qiu L, Chen YJ, Meng CT, Sun Z, Bai CM, et al. Chromogranin A is a reliable serum diagnostic biomarker for pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors but not for insulinomas. BMC Endocr Disord. 2014;14:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manta R, Nardi E, Pagano N, Ricci C, Sica M, Castellani D, et al. Pre-operative Diagnosis of Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors with Endoscopic Ultrasonography and Computed Tomography in a Large Series. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2016;25(3):317–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tang LH, Untch BR, Reidy DL, O’Reilly E, Dhall D, Jih L, et al. Well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors with a morphologically apparent high-grade component: A pathway distinct from poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(4):1011–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.The International Agency for Research on Cancer. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Digestive System. 4 edition. Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, Theise N, editor. World Health Organization; 2010. 418 p. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Edge SB, American Joint Committee on Cancer. AJCC cancer staging manual. Springer; 2010. 648 p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lawrence B, Gustafsson BI, Kidd M, Pavel M, Svejda B, Modlin IM. The Clinical Relevance of Chromogranin A as a Biomarker for Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2011;40(1):111–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Angelsen A, Syversen U, Haugen OA, Stridsberg M, Mjølnerød OK, Waldum HL. Neuroendocrine differentiation in carcinomas of the prostate: do neuroendocrine serum markers reflect immunohistochemical findings? Prostate. 1997. January 1;30(1):1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grabowski P, Schönfelder J, Ahnert-Hilger G, Foss HD, Stein H, Berger G, et al. Heterogeneous expression of neuroendocrine marker proteins in human undifferentiated carcinoma of the colon and rectum. Vol. 1014, Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2004. p. 270–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miki M, Ito T, Hijioka M, Lee L, Yasunaga K, Ueda K, et al. Utility of chromogranin B compared with chromogranin A as a biomarker in Japanese patients with pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2017;1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mosli HH, Dennis A, Kocha W, Asher LJ, Van Uum SHM. Effect of Short-Term Proton Pump Inhibitor Treatment and Its Discontinuation on Chromogranin A in Healthy Subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(9):E1731–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Waldum HL, Arnestad JS, Brenna E, Eide I, Syversen U, Sandvik AK. Marked increase in gastric acid secretory capacity after omeprazole treatment. Gut. 1996;39(5):649–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sanduleanu S, Stridsberg M, Jonkers D, Hameeteman W, Biemond I, Lundqvist G, et al. Serum gastrin and chromogranin A during medium- and long-term acid suppressive therapy: A case-control study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13(2):145–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arnold R, Wilke A, Rinke A, Mayer C, Kann PH, Klose KJ, et al. Plasma Chromogranin A as Marker for Survival in Patients With Metastatic Endocrine Gastroenteropancreatic Tumors. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6(7):820–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Qiu W, Christakis I, Silva A, Bassett RL, Cao L, Meng QH, et al. Utility of chromogranin A, pancreatic polypeptide, glucagon and gastrin in the diagnosis and follow-up of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 patients. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2016;85(3):400–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Laat JM, Pieterman CRC, Weijmans M, Hermus AR, Dekkers OM, de Herder WW, et al. Low accuracy of tumor markers for diagnosing pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(10):4143–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ito T, Igarashi H, Uehara H, Berna MJ, Jensen RT. Causes of death and prognostic factors in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1: A prospective study:Comparison of 106 men1/zollinger-ellison syndrome patients with 1613 literature men1 patients with or without pancreatic endocrine tumors. Med (United States). 2013;92(3):135–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kidd M, Bodei L, Modlin IM. Chromogranin A: any relevance in neuroendocrine tumors? Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2016. February;23(1):28–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]