Abstract

Adequate adherence to direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) for hepatitis C virus (HCV) is critical to attaining sustained virologic response (SVR). In this PREVAIL study’s secondary analyses, we explored the association between self-reported and objective DAAs adherence among a sample of people who inject drugs (PWID) receiving medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) (N = 147). Self-reported adherence was recoded 3 times during treatment (weeks 4, 8 and 12) using a visual analog scale (VAS), whereas objective adherence was collected continuously during treatment using electronic blister packs. Participants who reported being perfectly adherent had significantly higher blister pack adherence in each period (weeks 4, 8 and 12; ps < .05) and over the 12-week study (p < .001) compared to those who reported being non-perfectly adherent. Whites were more likely to report perfect adherence (91.7%) than Blacks (48.7%), Latinos (52.2%) and other (75.0%) race groups. Participants who reported recent use of cocaine (63.9%) or polysubstance use (60.0%) and those who had a positive result for cocaine (62.8%) were more likely to be non-perfectly adherent, although none of these factors were associated with blister pack adherence. This study showed that the VAS could serve as a reliable option for assessing DAAs adherence among PWID on MOUD. The implementation of VAS may be an ideal option for monitoring adherence among PWID on MOUD, especially in clinical settings with limited resources. PWID on MOUD who are Black or other races than White, as well as those who report recent cocaine or polysubstance use may require additional support to maintain optimal DAA adherence.

Keywords: direct-acting antiviral, hepatitis C virus, medications for opioid use disorder, people who inject drugs, self-reported Adherence

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Adequate adherence to direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) for hepatitis C virus (HCV) is critical to attaining sustained virologic response (SVR). Poor medication adherence can lead to negative health effects, including treatment failure and accelerated liver disease progression.1 Given the importance of adequate adherence to HCV medication, it is imperative to adequately measure and monitor patients’ adherence to medication.

Earlier studies conducted among people who inject drugs (PWID) and people receiving medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) have used various instruments to assess adherence to DAAs, including objective behavioural (eg electronic blister packs, electronic drug monitoring and pill count) and self-reported (eg visual analog scales (VAS), questionnaires) instruments. Behavioural instrument measurements are highly accurate2 and the most common approaches for determining adherence to DAAs in clinical trials conducted among PWID on a opioid agonist therapy (OAT) clinic setting.2–4,4 However, these instruments may not be practical in real-world settings due to the high cost, time consumption and complexity in managing data. Self-reported instruments, in contrast, may serve as a practical option for measuring HCV medication adherence in both clinical practice and research. Major advantages include ease of implementation, minimal work burden and low cost.5 Additionally, self-reported measurements of adherence deliver real-time information, which allows immediate actions to increase adherence and, therefore, can maximize the likelihood of SVR achievement. Thus, it is important to determine the extent to which the subjectively measured self-reported adherence reliably reflect medication adherence objectively measured by the behavioural instruments.

Studies in the DAA era have demonstrated that adherence among PWID receiving MOUD is high, including among those with recent injecting or drug use.6 Although these findings are promising, there are patients who show poor adherence patterns. Results from studies that have explored adherence among HCV patients that included PWID on MOUD have shown that suboptimal adherence to DAAs is associated with unstable housing, current depression, first missed dose within 4 weeks after treatment initiation, and both recent alcohol use and stimulant injecting.2–4,7,8 As is detailed above, most studies explored correlates of adherence based on behavioural instruments (ie electronic blister pack, pill count and medication dispensation data), with only one study that examined correlates of self-reported adherence.7 Furthermore, in the majority of these studies only a part of the sample was people receiving MOUD (7%–83%) or were PWID (38%–100%). To our knowledge, no study has focused on exploring self-reported adherence and its correlates in a sample of PWID on MOUD.

This study aimed at (1) establishing association between subjective self-reported HCV medication adherence through VAS and objective medication adherence measured through electronic blister packs among PWID maintained on MOUD (including people actively using drugs); and (2) identifying factors associated with perfect self-reported adherence.

2 |. METHODS

2.1 |. Participants

Participants were HCV-infected PWID receiving MOUD enrolled in the PREVAIL study, a randomized clinical trial aimed at exploring the effectiveness of three models of HCV care (NCT01857245).9 Participants were deemed eligible if they met the following criteria (1) were aged ≥ 18 years; (2) had HCV genotype 1, (3) were able to speak English or Spanish, (4) were psychiatrically stable, (4) agreed to receive HCV treatment on-site in their OAT programme and (5) were HCV treatment naïve (or treatment experienced with interferon-based regimens after December 2014).

2.2 |. Parent Clinical Trial: The PREVAIL study

In the PREVAIL study, Participants were randomized to self-administered individual treatment (SIT), group treatment (GT) or directly observed therapy (DOT). Participants randomized to SIT received all their medication packaged in 7-day blister packs from Opioid Treatment Programmes (OTP) clinic staff member and self-administered medications at home. Participants in the GT condition, in addition to self-administering medications at home, attended to weekly group support meetings. Participants in the DOT condition attended to their OTP clinic for in-person observation of medication ingestion which was linked to OTP visits. This intervention was considered modified DOT as not all doses were observed. The non-observed doses were dispensed in electronic blister packs as take-home doses for self-administration. Research visits were conducted at baseline, every 4 weeks during the first 12 weeks of treatment, at the end of treatment, and up to 24 weeks after treatment completion. Participants received the following HCV regimens: telaprevir, pegylated interferon and ribavirin (TVR/IFN/RBV); sofosbuvir, pegylated interferon and ribavirin (SOF/IFN/RBV); sofosbuvir and ribavirin (SOF/RBV); or a combination DAA regimen of sofosbuvir and simeprevir (SOF/SMV) or sofosbuvir/ledipasvir (SOF/LDV). Full study methodology has been described in detail elsewhere.9

2.3 |. Measures

At baseline, we collected information regarding sociodemographic characteristics (eg gender, age and ethnicity/race), recent alcohol and drug use (Addiction Severity Index-Lite),10 depressive symptoms (Beck Depression Inventory II),11 opiate withdrawal (Subjective Opiate Scale)12 and quality of life (EQ-5D-3L).13 Human Immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and diagnosis of a psychiatric or physical condition were obtained through chart review. Recent use of drugs (benzodiazepines, cocaine and opiates) was determined through urine test screening (American Biomedica Corporation, Kinderhook, NY).

Self-reported adherence was recoded 3 times during treatment (weeks 4, 8 and 12) using a VAS item “how much of your pills have you taken in the past 30 days?”. Participants were asked to estimate along a continuum from 0% to 100% on a visual scale. This measure of adherence was dichotomized into perfect adherence (ie response of 100% of doses taken) vs. non-perfect adherence (ie response of < 100% of doses taken).

Objective adherence was collected continuously during treatment using electronic blister packs. Blister pack data was used to calculate weekly (total doses removed every 7 days/7 days) adherence rates.

2.4 |. Data analysis

Participants who reported perfect adherence throughout the first 12 weeks of study (perfect group) and those who reported less than perfect adherence (non-perfect group) were compared on objective adherence rates through the first 12 weeks of study and baseline characteristics. For continuous variables, non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis tests were used to compare participants’ baseline characteristics between the perfect group and non-perfect self-report group. For categorical variables, chi-squared tests were used to compare participants baseline characteristics between the perfect group and non-perfect self-report group. Exact tests were performed to account for categorical variables with small cell counts. ANOVA was used to compare participants’ baseline characteristics on average blister pack adherence through the first 12 weeks. To assess whether differences between perfect and non-perfect self-report groups on blister pack adherence are confounded by differences in baseline characteristics, linear regression models were conducted to estimate the difference in blister pack adherence between perfect and non-perfect groups while adjusting for each baseline characteristic variable (one at a time).

Additional analyses compared perfect and non-perfect self-reported adherence and blister pack adherence at each 4-week interval using Kruskal–Wallis tests. Adjusted negative binomial regression was used to compare the perfect and non-perfect groups on average blister pack adherence throughout the 12-week study, incorporating age, race, gender and between-group baseline differences as covariates. The outcome, blister pack adherence, was inverted to meet distributional requirements. Thus, the results for negative binomial regression are to be interpreted as the effects of self-report on blister pack non-compliance.

Finally, to explore the association between SVR and both self-reported and blister pack adherence, we conducted t-tests comparing self-reported and blister pack adherence rates among those who achieved SVR (n = 139) and those who did not achieve SVR (ie treatment failures; n = 8). Statistical analyses were conducted using R, version 3.5.1.

3 |. RESULTS

Of the 150 PWID who initiated HCV treatment, three participants were excluded due to not having available adherence data leaving a final sample of 147 PWID. Briefly, participants were on average 51.4 (SD = 10.6) years old. The majority were male (64.6%) and Latino (62.6%). Forty-one per cent had less than high school education, 36.1% were married/living with a partner, 38.4% lived in marginalized housing, and 47.6% were unemployed. Average self-reported and blister pack adherence across treatment weeks was 94.9% and 78.2%, respectively (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the overall sample (N = 147) and by their self-reported adherence to DAAs

| Self-Reported Adherence |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Total (N = 147) | Non-Perfect (n = 66) | Perfect (n = 81) | p |

| Self-reported Adherencea | 94.9(11.5) | 88.5(14.9) | 100(0) | <.001 |

|

| ||||

| Blister pack Adherencea | 78.2 (17.3) | 73.2 (18.4) | 82.2 (15.3) | <.001 |

|

| ||||

| Agea | 51.4 (10.6) | 50.5 (11.2) | 52.1 (10.1) | .55 |

|

| ||||

| Race | .03 | |||

| Black/African American | 39 (26.5) | 20 (51.3) | 19 (48.7) | |

| White | 12 (8.16) | 1 (8.33) | 11 (91.7) | |

| Latino | 92 (62.6) | 44 (47.8) | 48 (52.2) | |

| Other race | 4 (2.72) | 1 (25.0) | 3 (75.0) | |

|

| ||||

| Gender | 1.00 | |||

| Male | 95 (64.6) | 43 (45.3) | 52 (54.7) | |

| Female | 52 (35.4) | 23 (44.2) | 29 (55.8) | |

|

| ||||

| Marital Status | .95 | |||

| Married/living with partner | 53 (36.1) | 24 (45.3) | 29 (54.7) | |

| Widowed/separated/divorced | 34 (23.1) | 16 (47.1) | 18 (52.9) | |

| Other marital status | 60 (40.8) | 26 (43.3) | 34 (56.7) | |

|

| ||||

| Education | .66 | |||

| Some high school or less | 61 (41.5) | 29 (47.5) | 32 (52.5) | |

| HS graduate/GED equivalent | 58 (39.5) | 25 (43.1) | 33 (56.9) | |

| Some college or more | 28 (19.0) | 12 (42.9) | 16 (57.1) | |

|

| ||||

| Employment Status | .30 | |||

| Employed | 13 (8.84) | 7 (53.8) | 6 (46.2) | |

| Unemployed | 70 (47.6) | 27 (38.6) | 43 (61.4) | |

| Disabled or retired | 57 (38.8) | 27 (47.4) | 30 (52.6) | |

| Other employment status | 7 (4.76) | 5 (71.4) | 2 (28.6) | |

|

| ||||

| Living Situation | .75 | |||

| Marginalized Housing | 53 (38.4) | 25 (47.2) | 28 (52.8) | |

| Institution (halfway house) | 8 (5.80) | 3 (37.5) | 5 (62.5) | |

| Own/Rents apartment, house or room | 69 (50.0) | 30 (43.5) | 39 (56.5) | |

| Other | 8 (5.80) | 5 (62.5) | 3 (37.5) | |

|

| ||||

| Psychiatric Conditions | ||||

| Depression | .14 | |||

| No | 75 (51.0) | 29 (38.7) | 46 (61.3) | |

| Yes | 72 (49.0) | 37 (51.4) | 35 (48.6) | |

| Anxiety | .27 | |||

| No | 106 (72.1) | 51 (48.1) | 55 (51.9) | |

| Yes | 41 (27.9) | 15 (36.6) | 26 (63.4) | |

| Bipolar | 1.00 | |||

| No | 126 (85.7) | 57 (45.2) | 69 (54.8) | |

| Yes | 21 (14.3) | 9 (42.9) | 12 (57.1) | |

| Psychosis | 1.00 | |||

| No | 141 (95.9) | 63 (44.7) | 78 (55.3) | |

| Yes | 6 (4.08) | 3 (50.0) | 3 (50.0) | |

| OCD | 1.00 | |||

| No | 146 (99.3) | 66 (45.2) | 80 (54.8) | |

| Yes | 1 (0.68) | 0.0 (0.0) | 1 (100) | |

| PTSD | .77 | |||

| No | 134 (91.2) | 61 (45.5) | 73 (54.5) | |

| Yes | 13 (8.84) | 5 (38.5) | 8 (61.5) | |

|

| ||||

| Physical Conditions | ||||

| Cirrhosis | .85 | |||

| No | 106 (72.1) | 47 (44.3) | 59 (55.7) | |

| Yes | 41 (27.9) | 19 (46.3) | 22 (53.7) | |

| HIV | .49 | |||

| No | 126 (85.7) | 55 (43.7) | 71 (56.3) | |

| Yes | 21 (14.3) | 11 (52.4) | 10 (47.6) | |

|

| ||||

| Quality of Life | ||||

| Mobility | .25 | |||

| No problems | 76 (51.7) | 38 (50.0) | 38 (50.0) | |

| Some/many problems | 71 (48.3) | 28 (39.4) | 43 (60.6) | |

| Self-care | 1.00 | |||

| No problems | 125 (85.0) | 56 (44.8) | 69 (55.2) | |

| Some/many problems | 22 (15.0) | 10 (45.5) | 12 (54.5) | |

| Usual Activities | .62 | |||

| No problems | 78 (53.1) | 37 (47.4) | 41 (52.6) | |

| Some/many problems | 69 (46.9) | 29 (42.0) | 40 (58.0) | |

| Pain/discomfort | .44 | |||

| No problems | 35 (23.8) | 18 (51.4) | 17 (48.6) | |

| Some/many problems | 112 (76.2) | 48 (42.9) | 64 (57.1) | |

| Anxiety/Depression | .73 | |||

| No problems | 49 (33.3) | 23 (46.9) | 26 (53.1) | |

| Some/many problems | 98 (66.7) | 43 (43.9) | 55 (56.1) | |

| Depressive Symptoms | .25 | |||

| ≤ 13 | 73 (49.7) | 29 (39.7) | 44 (60.3) | |

| >13 | 74 (50.3) | 37 (50.0) | 37 (50.0) | |

| Subjective opiate withdrawal | .49 | |||

| Mild withdrawal | 108 (74.0) | 50 (46.3) | 58 (53.7) | |

| Moderate withdrawal | 24 (16.4) | 8 (33.3) | 16 (66.7) | |

| Severe withdrawal | 14 (9.59) | 7 (50.0) | 7 (50.0) | |

|

| ||||

| Past 30 days use | ||||

| Self-reported use of alcohol | .15 | |||

| No | 101 (68.7) | 41 (40.6) | 60 (59.4) | |

| Yes | 46 (31.3) | 25 (54.3) | 21 (45.7) | |

| Self-reported use alcohol (to intoxication) | .44 | |||

| No | 112 (76.2) | 48 (42.9) | 64 (57.1) | |

| Yes | 35 (23.8) | 18 (51.4) | 17 (48.6) | |

| Self-reported use of heroin | 1.00 | |||

| No | 119 (81.0) | 53 (44.5) | 66 (55.5) | |

| Yes | 28 (19.0) | 13 (46.4) | 15 (53.6) | |

| Self-reported use of methadone | .45 | |||

| No | 1 (0.68) | 1 (100) | 0.0 (0.0) | |

| Yes | 146 (99.3) | 65 (44.5) | 81 (55.5) | |

| Self-reported use of other opiates | .84 | |||

| No | 115 (78.2) | 51 (44.3) | 64 (55.7) | |

| Yes | 32 (21.8) | 15 (46.9) | 17 (53.1) | |

| Self-reported use of barbiturates | .22 | |||

| No | 141 (95.9) | 65 (46.1) | 76 (53.9) | |

| Yes | 6 (4.08) | 1 (16.7) | 5 (83.3) | |

| Self-reported use of sedatives | .15 | |||

| No | 116 (78.9) | 56 (48.3) | 60 (51.7) | |

| Yes | 31 (21.1) | 10 (32.3) | 21 (67.7) | |

| Self-reported use of cocaine | .01 | |||

| No | 111 (75.5) | 43 (38.7) | 68 (61.3) | |

| Yes | 36 (24.5) | 23 (63.9) | 13 (36.1) | |

| Self -reported use of cannabis | .72 | |||

| No | 103 (70.1) | 45 (43.7) | 58 (56.3) | |

| Yes | 44 (29.9) | 21 (47.7) | 23 (52.3) | |

| Self-reported use of hallucinogens | .06 | |||

| No | 142 (96.6) | 66 (46.5) | 76 (53.5) | |

| Yes | 5 (3.40) | 0.0 (0.0) | 5 (100) | |

| Self -reported use of inhalants | 1.00 | |||

| No | 146 (99.3) | 66 (45.2) | 80 (54.8) | |

| Yes | 1 (0.68) | 0.0 (0.0) | 1 (100) | |

| Self-reported polysubstance use | .05 | |||

| No | 112 (76.2) | 45 (40.2) | 67 (59.8) | |

| Yes | 35 (23.8) | 21 (60.0) | 14 (40.0) | |

|

| ||||

| Urine Drug Screen | ||||

| Any Drugs | .19 | |||

| No | 76 (51.7) | 30 (39.5) | 46 (60.5) | |

| Yes | 71 (48.3) | 36 (50.7) | 35 (49.3) | |

| Opioids/oxycodone | .25 | |||

| No | 110 (74.8) | 46 (41.8) | 64 (58.2) | |

| Yes | 37 (25.2) | 20 (54.1) | 17 (45.9) | |

| Cocaine | .01 | |||

| No | 104 (70.7) | 39 (37.5) | 65 (62.5) | |

| Yes | 43 (29.3) | 27 (62.8) | 16 (37.2) | |

| Benzodiazepines | .81 | |||

| No | 127 (86.4) | 58 (45.7) | 69 (54.3) | |

| Yes | 20 (13.6) | 8 (40.0) | 12 (60.0) | |

Note:: Variables reported as mean (M) and (SD), otherwise as N (%).

Boldface indicates statistical significance (P<.05).

Variables may not add to N due to missing data.

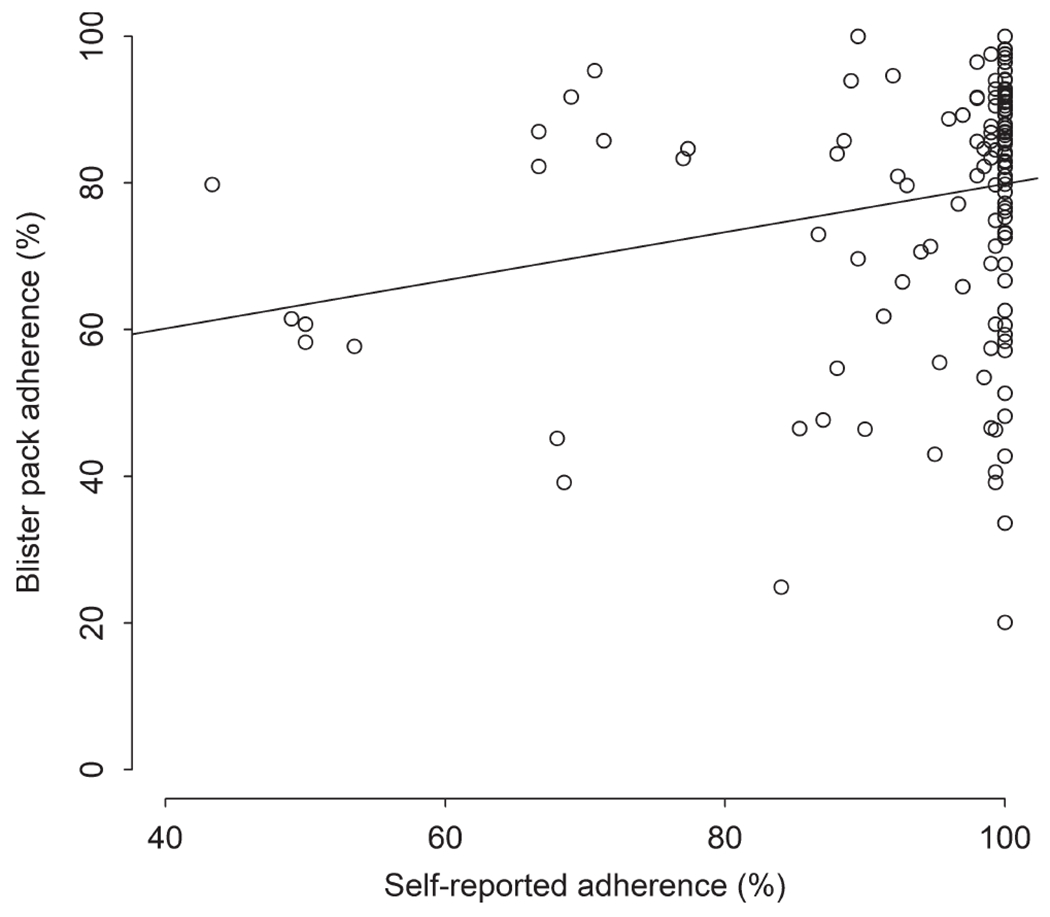

Fifty-five per cent of the participants (81/147) reported being perfectly adherent to the HCV medication and 44.9% (66/147) reported non-perfectly adherent (Table 1). Blister pack adherence was 73.2% among those who reported non-perfect adherence, and 82.2% among those who reported perfect adherence (p < .001). Spearman’s correlation coefficient showed a positive significant association between both measures of adherence, r = 0.29, p < .001 (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Patient self-reported adherence compared with blister pack data

Whites were more likely to report perfect adherence (91.7%) than individuals who were Black (48.7%), Latino (52.2%) and Other (75.0%), p = .03. Participants who reported recent use of cocaine (63.9%, p = .01) or polysubstance use (60.0%, p = .05), and those who had a positive result for cocaine (62.8%, p = .01) were more likely to be non-perfectly adherent (Table 1).

Table S1 shows results exploring the association between baseline factors and blister pack adherence. The only factor associated with objective adherence was depressive symptoms. More specifically, we found that those participants with scores ≤ 13 on the BDI-II had higher adherence rates compared to those with BDI scores >13 (82.0% vs 74.3%, p = .01).

When comparing perfect and non-perfect groups on objective blister pack adherence, while adjusting for each variable in Table 1/Table S2 (one at a time), regression models showed that the differences between perfect and non-perfect groups were significant across variables with differences ranging from 8.6% and 9.4%. The results of these regression analyses are presented in Table S2 and provide evidence that the difference between self-report groups (9%) was not confounded by differences in baseline characteristics.

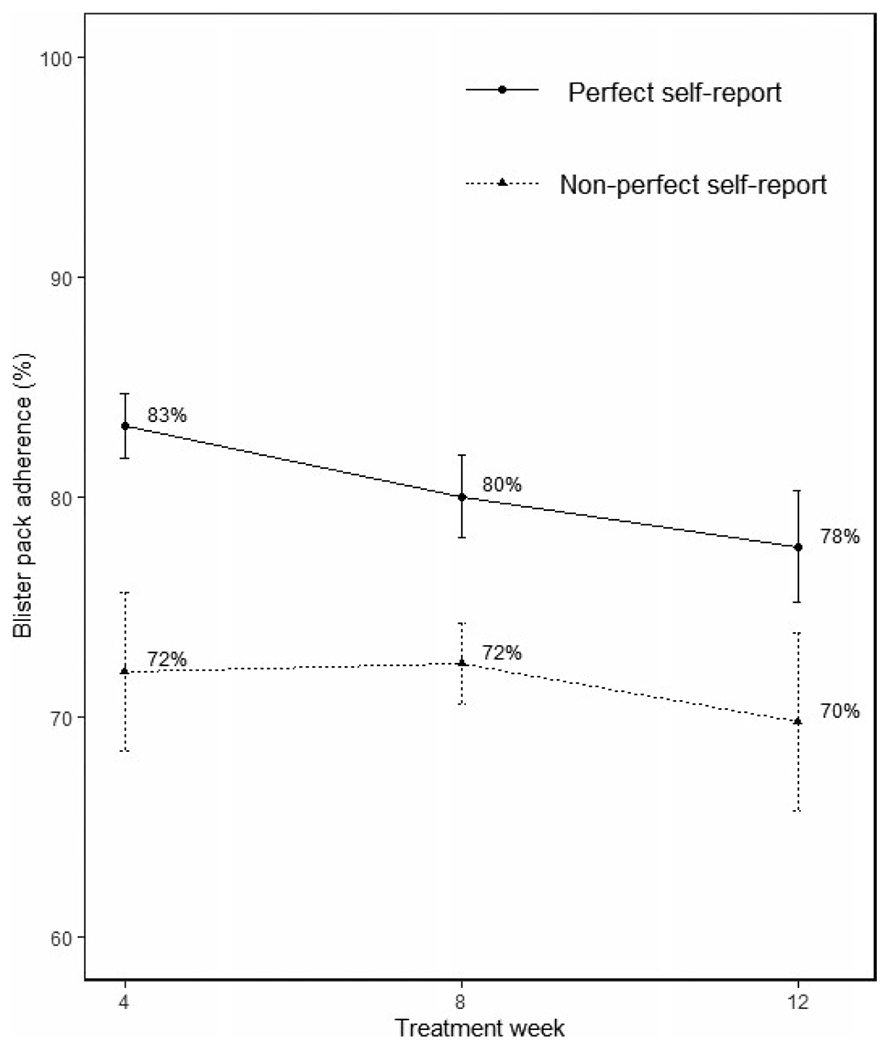

When comparing perfect self-reported vs blister pack adherence at each 4-week treatment (Figure 2), we found that the perfect group had significantly higher blister pack adherence in each period (week 4: difference = 11%, p = .004; week 8: difference = 8%, p = .031; week 12: difference = 8%, p = .021). Adjusted negative binomial regression concluded the perfect group missed 52% less days of blister pack compared to the non-perfect group (p = .003).

FIGURE 2.

Blister pack adherence as a function of perfect vs non-perfect self-reported adherence. Perfect and non-perfect groups significantly different at all treatment weeks (week 4: P=.004; week 8: P =.031; week 12: P =.021)

Finally, we compared both self-reported and blister pack adherence among those who achieved SVR (n = 139) and those who failed HCV cure (n = 8). We found that blister pack adherence was higher among those who achieved SVR (79.2%, SD = 16.2) than those who failed to achieve SVR (61.0%, SD = 27.1%; P = .10). We also found that self-reported adherence was higher among those who achieved SVR (95.0%, SD = 11.5) than those who failed to achieve SVR (92.4%, SD = 11.4%; P= .55). However, between-group differences were not statistically significant.

3.1 |. Discussion

In this secondary analysis from the PREVAIL Study, we explored correlates of perfect self-reported adherence based on VAS among PWID with recent drug use who are receiving MOUD; and examined the reliability of a self-reported measure of adherence to DAAs objectively measured by electronic blister pack. We highlight three major findings: (1) perfect self-reported adherence is a good indicative of greater blister pack adherence measurements; (2) being Black or other races than White, recent cocaine or polysubstance use, and urine positive for cocaine at baseline were associated with non-perfect self-reported adherence; and (3) high adherence to DAAs measured both by self-reported and behavioural instruments was observed.

We found that perfect DAA adherence among PWID on MOUD as measured by a VAS was congruent with an objective, behavioural measure of adherence (blister pack) in terms that individuals who reported perfect adherence also showed greater adherence in blister pack data. Recent studies have demonstrated that self-reported measures of DAA adherence provide similar results to behavioural measures, including pill counts and pharmacy dispensing, among people infected with HCV, some of which being PWID.5,14 This study contributes to the existing literature on the utility of self-reported measures as an indicator of adherence and expands these findings among PWID maintained on MOUD with recent drug use and by using a more accurate measure of objective adherence (ie electronic blister packs). The availability of both brief and reliable instruments of assessing DAAs adherence among HCV-infected patients could be useful for both clinical practice and research studies, and may hold particular promise for clinical settings with limited resources or in rural areas. Overall, our results evidence that the VAS provides adherence data that is reliable and useful in clinical trials involving HCV-infected PWID on MOUD. Future studies should explore whether the VAS can be utilized as a practical and reliable measure of DAAs adherence in real-world clinical settings.

Another important finding was that being Black, Latino or Other race than White was associated with non-perfect self-reported adherence. Non-White or Black race has been shown to be associated with poor self-reported adherence to DAA medication among HCV-infected individuals with recent drug use in the past year.15 Our finding is novel in the context that our study included PWID with active drug use and receiving MOUD. The association between non-perfect adherence and Black race is somewhat puzzling. However, we surmise that low perfect self-reported adherence observed among Blacks may be related to the fact that Blacks typically show lower levels of trust towards to health care providers and medications.16–18 In this regard, there is previous evidence indicating that Black who do not trust their providers are more likely to not be adherent to their prescribed medication for other health conditions including hypertension, bowel disease.19–21 as well as adherence to treatment protocols (eg routine checkups or tests) and preventive services.16,22 As such, our finding may be alarming as poorer adherence among Blacks can lead to reduced likelihood of achieving SVR, a population who already present lower SVR rates relative to Whites.6,23 Furthermore, Blacks and people with other non-White ethnicities represent the highest prevalence of individuals infected with HCV in the United States24 and not effectively treating this portion of population may impede our efforts to eradicate HCV in the country. Overall, this finding may underline the need for implementing culturally appropriate components that are tailored for non-White communities in order to achieve health equality and reduce health disparities in the context of HCV treatment. Perhaps one potential approach could be the implementation of models of care that encourage and improve rapport between patients and providers through patient-centred care. In addition to the race, we found that recent cocaine or polysubstance use, and urine positive for cocaine at baseline were associated with non-perfect self-reported adherence. This finding is consistent with earlier studies that have shown that recent stimulant injection was associated with nonadherence among PWID, people receiving MOUD or both.2,4 These results, however, should not be interpreted to mean that recent drug use has an impact on other HCV outcomes. In fact, there is recent evidence indicating that PWID on MOUD with suboptimal objective adherence are able to achieve SVR in the DAA era.25 Finally, it is also important to note that overall adherence rates were high, but most participants did not have perfect blister pack adherence. Thus, our results may alternatively suggest that Blacks and people who reported recent drug use provide a more accurate estimate of adherence than patients of other races or those who did not report recent drug use. A potential explanation may be related to the nature of the adherence assessment. Self-report information is susceptible to social desirability bias which could make some individuals provide adherence information that they think is more desirable or acceptable. Our finding may indicate that that Blacks and individuals who voluntarily admitted their drug use may be less influenceable to social desirability bias.

Lastly, our finding of very high adherence among PWID with recent and active drug use receiving MOUD treatment as measured both by self-reported and behavioural measures is consistent with earlier studies.2,4 It is noteworthy that these studies included PWID with recent injection drug use and people on MOUD and the concurrence of both conditions (recent injection and MOUD) was present only in a portion of the sample. It is also important to highlight that studies involving analyses of adherence among PWID, either receiving or not receiving MOUD, including the current study, are clinical trials within controlled settings and highly protocolized procedures. So, the methods followed in these studies could have contributed to an adherence facilitation strategy. It is imperative in future research to explore DAAs adherence in real-world clinical practice settings among typical PWID patients in order to determine if these findings are generalizable to PWID on MOUD populations. Taken together, our finding in addition with earlier literature further evidences that concerns about suboptimal adherence among PWID on MOUD should not be considered by health care providers to withhold HCV treatment in this population.

Several limitations should be noted. First, self-reported adherence was measured every 4 weeks whereas blister pack adherence was measured weekly. Second, all patients did not receive the same combination of HCV medication. It should be mentioned that the parent study did not find differences in HCV treatment outcomes as a function of the DAA regimen.9 Third, only a small (8.1%) percentage of participants were White or Black which limits our ability to further explore racial/ethnic disparities in DAAs adherence.

In summary, the VAS was a reliable option for assessing DAA adherence among PWID on MOUD. The implementation of VAS may be a practical option for monitoring adherence among PWID on MOUD, especially in clinical settings with limited resources or in rural areas. PWID on MOUD who are Black or other races than White, as well as those who report recent cocaine use or polysubstance use may require additional support to maintain optimal DAA adherence.

Supplementary Material

FUNDING INFORMATION

This work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse [R01DA034086] and Gilead Sciences [IN-337-1779].

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

AHL is a consultant/advisor and has received research grants from AbbVie, Gilead Sciences and Merck Pharmaceuticals.

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1.Benítez-Gutiérrez L, Barreiro P, Labarga P, et al. Prevention and management of treatment failure to new oral hepatitis C drugs. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2016;17:1215–1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cunningham EB, Hajarizadeh B, Amin J, et al. Adherence to once-daily and twice-daily direct acting antiviral therapy for hepatitis C infection among people with recent injection drug use or current opioid agonist therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:e115–e124. 10.1093/cid/ciz1089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown A, Welzel TM, Conway B, et al. Adherence to pan-genotypic glecaprevir/pibrentasvir and efficacy in HCV-infected patients: a pooled analysis of clinical trials. Liver Int. 2020;40:778–786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cunningham EB, Amin J, Feld JJ, et al. Adherence to sofosbuvir and velpatasvir among people with chronic HCV infection and recent injection drug use: The SIMPLIFY study. Int J Drug Policy. 2018;62:14–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fernández C, de Sevilla MÁ, Gallego Úbeda M, et al. Measure of adherence to direct-acting antivirals as a predictor of the effectiveness of hepatitis C treatment. Int J Clin Pharm. 2019;41:1545–1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benhammou JN, Dong TS, May FP, et al. Race affects SVR12 in a large and ethnically diverse hepatitis C-infected patient population following treatment with direct-acting antivirals: Analysis of a single-center Department of Veterans Affairs cohort. Pharmacol Res Perspect. 2018;6:e00379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mason K, Dodd Z, Guyton M, et al. Understanding real-world adherence in the directly acting antiviral era: a prospective evaluation of adherence among people with a history of drug use at a community-based program in Toronto, Canada. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;47:202–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Read P, Gilliver R, Kearley J, et al. Treatment adherence and support for people who inject drugs taking direct-acting antiviral therapy for hepatitis C infection. J Viral Hepat. 2019;26:1301–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akiyama MJ, Norton BL, Arnsten JH, Agyemang L, Heo M, Litwin AH. Intensive models of Hepatitis C care for people who inject drugs receiving opioid agonist therapy: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Inter Med. 2019;170:594–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McLellan AT, Cacciola JS, Zanis D. The Addiction Severity Index-Lite. Center for the Studies on Addiction. University of Pennsylvania/Philadelphia VA Medical Center. 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown G. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Handelsman L, Cochrane KJ, Aronson MJ, Ness R, Rubinstein KJ, Kanof PD. Two new rating scales for opiate withdrawal. Am J Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 1987;13:293–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brooks R EuroQol: the current state of play. Health Policy. 1996;37:53–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burton MJ, Voluse AC, Patel AB, Konkle-Parker D. Measuring adherence to hepatitis C direct-acting antiviral medications: using the VAS in an HCV treatment clinic. South Med J. 2018;111:45–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Serper M, Evon DM, Stewart PW, et al. Medication non-adherence in a prospective, multi-center cohort treated with Hepatitis C direct-acting antivirals. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;35:1011–1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Musa D, Schulz R, Harris R, Silverman M, Thomas SB. Trust in the health care system and the use of preventive health services by older black and white adults. Am J Public Health. 2009;9:1293–1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shoff C, Yang T-C. Untangling the associations among distrust, race, and neighborhood social environment: a social disorganization perspective. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74:1342–1352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Armstrong K, McMurphy S, Dean LT, et al. Differences in the patterns of health care system distrust between blacks and whites. J Gen Inten Med. 2008;23:827–833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abel W, Efird J. The association between trust in health care providers and medication adherence among black women with hypertension. Front Public Health. 2013;1:66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cuffee YL, Hargraves JL, Rosal M, et al. Reported racial discrimination, trust in physicians, and medication adherence among inner-City African Americans with hypertension. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(11):e55–e62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nguyen GC, LaVeist TA, Harris ML, Datta LW, Bayless TM, Brant SR. Patient trust-in-physician and race are predictors of adherence to medical management in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:1233–1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Malley AS, Sheppard VB, Schwartz M, Mandelblatt J. The role of trust in use of preventive services among low-income African-American women. Prev Med. 2004;38:777–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Su F, Green PK, Berry K, Ioannou GN. The association between race/ethnicity and the effectiveness of direct antiviral agents for hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology. 2017;65:426–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bradley H, Hall EW, Rosenthal EM, Sullivan PS, Ryerson AB, Rosenberg ES. Hepatitis C virus prevalence in 50 US states and DC by Sex, birth cohort, and race: 2013–2016. Hepatol Commun. 2020;4:355–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Norton BL, Akiyama MJ, Agyemang L, Heo M, Pericot-Valverde I, Litwin AH. Low adherence achieves high HCV cure rates among people who inject drugs treated with direct-acting antiviral agents. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020;7:ofaa377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.