Abstract

Many older adults wish to age-in-place but do not have long-term care plans for when they may require more assistance. PlanYourLifespan.org (PYL) is an evidence-based tool that helps older adults understand and plan for their long-term care needs. We examined the long-term effects of PYL use on user perceptions and planning of long-term care services. Individuals who previously accessed PYL were invited to complete an online, nation-wide mixed methodology survey about end-user outcomes related to PYL. Among 115 completed surveys, users found PYL helpful with long-term planning for their future needs. Over half of website users reported having conversations with others because of PYL use. However, 40% of respondents reported not having a conversation with others about their plans; common themes for barriers to planning included procrastination and a lack of immediate support needs. Although PYL helps with planning, many people are still not communicating their long-term care plans.

Keywords: aging-in-place, older adults, advance care planning interventions, advance health events

Introduction

Aging-in-place is a priority for many older adults and planning for social support needs is critical to success (Gillsjo et al., 2011). Aging-in-place is defined as the ability to live in one’s own home and community safely, independently, and comfortably, regardless of age, income, or ability level (Centers for Disease Control, 2020). Older adults have to navigate resources to balance their age-related changes (e.g., worsening cognition, increasing disability) with their needs (Avery et al., 2010; Ball et al., 2004). The lifetime probability of becoming disabled in at least two activities of daily living or of being cognitively impaired is 68% for people age 65 and older (Yondorf, 2005). By 2050, the number of individuals using paid long-term care services in any setting will be close to 27 million people (Seplaki et al., 2014; Tang & Lee, 2010). Although many older adults will need support, prior research has shown that older adults may dismiss planning for their home support needs outright (e.g. I plan to die in my sleep before I ever need help) (Lindquist et al., 2016). A common fear observed among older adults is removal from their homes and placement in long-term care institutions (Ramirez-Zohfeld et al, 2016). The majority of older adults do not want to leave their homes and yet very few plan for needs that they may require to age-in-place safely.

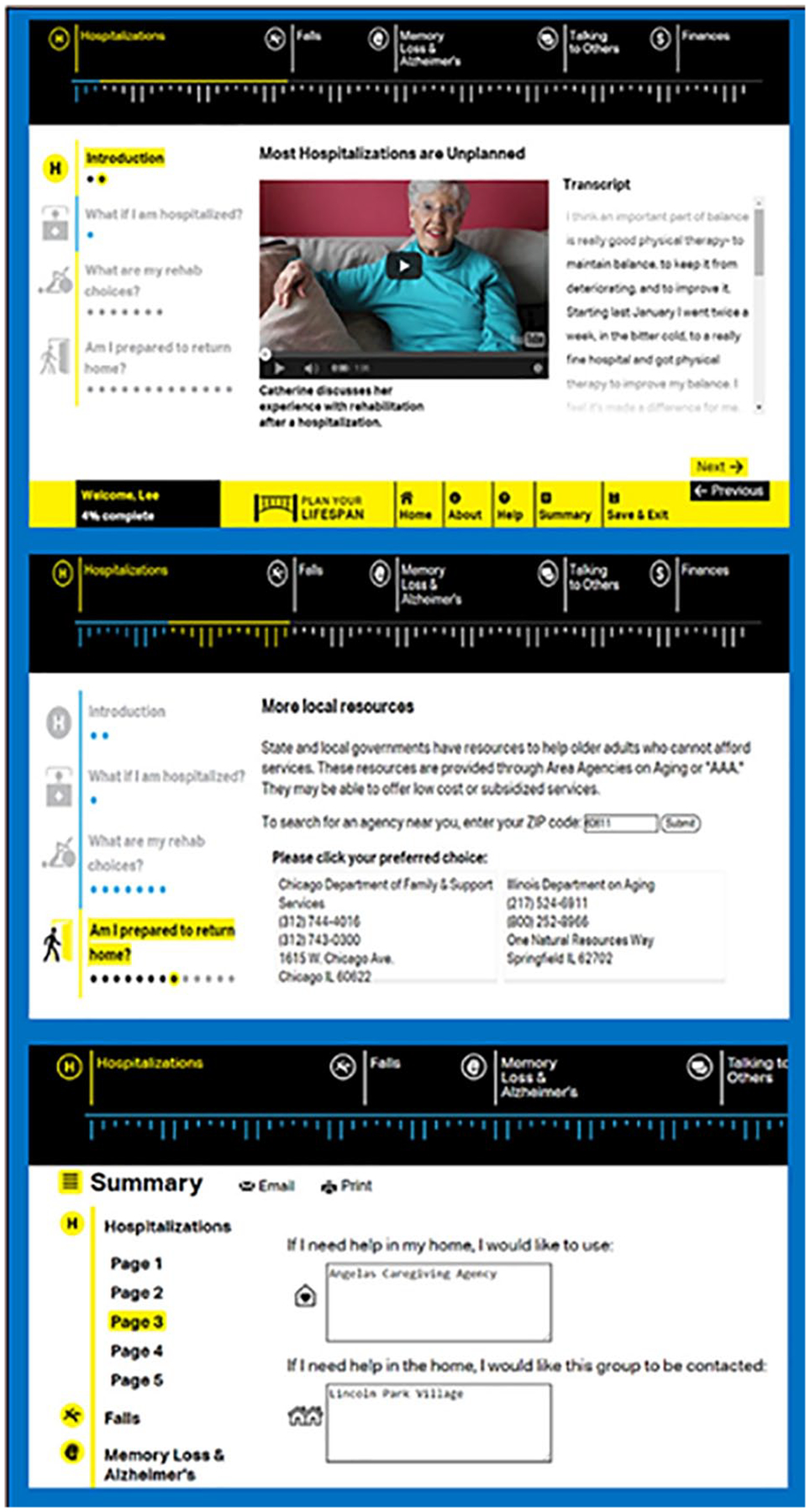

Through our previous research, we developed a web-based tool, PlanYourLifespan.org (PYL) (Figure 1), which facilitates decision-making and planning to age-in-place. PYL does not focus on planning for end-of-life, but rather the period 10–20 years before when older adults may require more assistance in the home (Lindquist et al., 2010). PYL educates on the health crises that often occur with older age and connects users to home-based resources available locally and nationally that can assist now or in the future (Lindquist et al., 2017). PYL was tested in a multisite randomized controlled trial of 385 community-dwelling older adults with a 3-month follow-up and was found to be significantly efficacious in improving decision-making behaviors toward aging-in-place options among older adults (Lindquist et al., 2010). With a 3-month follow-up, we were limited in determining how the decision-making plans of older adults ultimately translated into implementation and aging-in-place. Variability was also detected in how older adults made and communicated their decision-making goals toward aging-in-place.

Figure 1.

Snapshot of PlanYourLifespan.org.

A gap exists in how time affects planning and decisions about aging-in-place. We examined how older adults translated their plans into implementation as well as the impact that planning had on communication about these plans with others up to 5 years after their initial use of PYL. Closing these gaps is critical to assisting older adults and their loved ones in making choices about their aging-in-place futures.

Design and Methods

Study Population

Users who previously accessed PYL and registered with an email account were invited to participate in an online survey to ascertain specific end-user outcomes related to their use of the website. Email solicitation to participate was conducted in two waves: Wave 1 included PYL users who registered with an email address between September 2014 and June 2018. Wave 2 invited PYL users who registered between July 1, 2018 and January 31, 2019.

Data Sources and Measures

The online survey included questions related to the individual’s use of PYL, whether PYL affected their planning and aided in decision-making, and whom they shared PYL and their plans with. In addition, demographic information was collected. The survey was designed to take approximately 15–20 min to complete.

Analysis

Results.

Across both survey waves, a total of 2,280 survey invitations were sent out and 115 surveys were completed, with survey Wave 1 having a slightly higher response rate (5.2%) than survey wave 2 (3.9%). A majority of survey respondents were 55–75 years and older, with 20.6% (n = 15) being age 55–64 years old; 41.1% (n = 30) 65–74 years old, and 23.3% (n = 17) 75 years or older. Respondents were predominately female (76.7%, n = 56) and White (91.8%, n = 67). Most respondents had used PYL within the past 2 years, with 21.7% (n = 25) reporting having first used the website less than 6 months ago, 21.7% (n = 25) reported having first used the website 6–12 months ago, and 17.4% (n = 20) 1–2 years ago. Over half (57.9%, n = 73) have used PYL for themselves, and 15.9% (n = 20) reported using it for a loved one (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Individuals Completing Survey (n = 115).

| Characteristic Sex (n = 73) |

Percentage (n) |

|---|---|

| Female | 76.7% (56) |

| Male | 23.3% (17) |

| Age range (years, n = 73) | |

| 25–34 | 1.37% (1) |

| 35–44 | 4.11% (3) |

| 45–54 | 9.59% (7) |

| 55–64 | 20.55% (15) |

| 65–74 | 41.10% (30) |

| 75 and older | 23.29% (17) |

| Race (n = 115) | |

| White | 58.2% (67) |

| Black or African American | 0.02% (2) |

| Asian | 0.02% (2) |

| Prefer not to say/no response | 38.3% (44) |

| First use of PYL (n = 115) | |

| Less than 6 months | 21.74% (25) |

| 6–12 months | 21.74% (25) |

| 1–2 years | 17.39% (20) |

| 3–4 years | 6.09% (7) |

| More than 5 years | 1.74% (2) |

| Not sure | 31.30% (36) |

| Accessed PYL for: | |

| Yourself | 57.94% (73) |

| Loved one | 15.87% (20) |

| Client/customer of your workplace | 4.76% (6) |

| Other | 1.59% (2) |

| Not sure/don’t know | 19.84% (25) |

| Type of experienced health crisis | |

| Fall(s) | 9.73% (11) |

| Hospitalization | 7.96% (9) |

| Emergency department visit | 9.73% (11) |

| Skilled nursing facility stay | 0.88% (1) |

| Worsening memory loss | 3.54% (4) |

| None | 66.37% (75) |

Note. PYL = PlanYourLifespan.org.

Since accessing the PYL website, over 66% of survey respondents did not report any health crises. Eleven people reported having experienced a fall, and four people reported having worsening memory loss. Eleven people visited an emergency department, nine people had a hospitalization, and one person experienced a skilled nursing facility stay. Among those who experienced a health crisis and accessed PYL, they reported communicating with loved ones and making specific considerations for future planning, such as post-acute care and medication management. A few notable quotes are as follows:

Planning surgery and rehab—picking my own rehab facility and managing my medication

… put aging in perspective and made me think about the “bigger picture”

It helped all 5 siblings be realistic about risk, since some minimize problems and others are too anxious

People who used PYL but did not experience a health crisis also found the website helpful in making decisions about their future (43.6%, n = 44), as they felt that it was most helpful for long-term planning and organizing their goals and wishes for future care.

Forced me to be specific about decisions I might have to make in the future.

It helped me organize my thoughts, and prompted me to think about things I hadn’t considered.

It provided a clear process for considering each aspect of aging needs.

They also shared that PYL was helpful in planning for loved ones or assisting clients with plan creation.

… helped me to broach topic of managing my parents’ savings for their final years with my 4 older siblings

A few users found PYL useful for weighing post-acute care options, identifying community resources, and home safety considerations.

Learned what the different rehab options are, and was able to access the Medicare link that shows the different nursing home rehab options near me.

It identified being aware of rehab facilities before your need of one so that you can make an informed decision in a short period of time if necessary.

PYL also helped users identify resources. Some people focused on specific resources such as supportive living environments, fall prevention, and durable medical equipment. Others broached this subject more generally, describing that PYL served as a “checklist” for important considerations.

Looked into all senior options within the city.

Community/Group living arrangements

Resource lists and check lists were useful

Caused me to look at putting my name on list for continuing care facility

I am considering a chair lift for my house, my funeral arrangements, and will think about an assisted living space.

Over half of respondents (58.5%, n = 48) stated that since using PlanYourLifespan.org, they had had conversations with others about their future plans. The majority of individuals reported that they talked with their spouse/partner and/or adult children. Others shared that they had conversations with friends and siblings and one individual reported sharing this content with their financial planner. The content of the conversations appeared to mostly focus on future health care planning and living arrangements that provide greater levels of care:

Talked with family, friends, coworkers about the need to plan and the options within the city.

When to sell home or where to go for independent living with future options

Whether to stay in our home or move; downsizing; cremation

Spoke with my children about my estate and gave them copies of my estate plan.

PYL users who reported they had not yet had conversations since viewing the website (35.6%, n = 30) were asked why they had not done so. Reasons focused on procrastination and the lack of an immediate need for future care planning. Some noted that they were not interested in having these conversations and would enjoy the present instead.

It is a tough subject to bring up, especially since I am fortunate to be healthy and relatively young still. If I start to plan things so early, it may not be relevant anymore for if/when I need it in the future.

Seems that significant others have their life demands and want to deny the need for preplanning. As well I would rather look at other more appealing realities … like quality of life today.

I’m not old enough to make it feel necessary.

I just turned 67 and I’m married so I have less immediate worry about needing these services. But sooner or later, we ALL will need them!

Not a topic that has been particularly pressing, and I have lots of other things on my mind.

One person highlighted an important issue that likely affects a number of seniors—not having any relatives or next of kin to discuss long-term care needs with.

Alone, all relatives deceased; only have 2 friends I’m close to—seldom see them.

Discussion

Since its development in 2014, PlanYourLifespan.org has assisted older adults and their families in understanding and planning for their aging-in-place and long-term care needs. In this study, we examined the impact that PYL had on users up to 5 years after their initial website use. Survey results showed that most people found PYL helped them think through their long-term needs and concrete actionable plans. About half of the users reported having a health event since using PYL. Older adults noted that they used PYL to plan for posthospitalization needs (e.g., checklists, rehabilitation needs, identifying skilled nursing facility), to consider home remodeling, and alternatively, to place their names on waiting lists at older adult residential communities.

A key premise is the need to communicate these aging-in-place and long-term care plans with loved ones—as many of the loved ones will be implementing these plans in the event the older adult experiences a health crisis. Over half of PYL users reported having conversations with others about their future health plans, mostly discussing it with their spouse/partner and/or adult children. Other users (35.6%) made plans but had not communicated them to others. This provides an opportunity for further research—how to make discussing aging-in-place and long-term care needs easier and more engaging.

As with all studies, limitations existed. The survey was offered to all registered users over the past 5 years, online, and without compensation. The response rate was low and perhaps could be improved by offering compensation as well as providing other modality options to completing the survey. While there were a number of people who experienced a health event, there is the possibility that survey participants that had experienced a significant health crisis (e.g., worsening Alzheimer’s) were not able to complete the survey so we may be underreporting these events. With these individuals, we would also not be able to explain if PYL had affected their choices. The time span of 5 years may have also been an insufficient number of years for users to experience a support need and allow us to measure the impact PYL may have made. Several subjects stated that they were healthy and did not yet need to implement or communicate plans.

Those who did not communicate their plans with others because they were healthy identified the barrier of procrastination. Although people feel healthy, there may come a time when they need additional support in the home. Early planning and communication with others is paramount to enable personal aging-in-place and long-term care goals to be implemented. Determining how to overcome procrastination and encouraging planning prior to health crises are areas where further research needs to continue.

Conclusion

PlanYourLifespan.org continues to be helpful in assisting older adults and their families with understanding and planning for aging-in-place and long-term care needs. Several PYL users experienced health crises requiring support services and found PYL useful in implementing plans and communicating with loved ones. Further research is needed to determine how to overcome procrastination in communicating plans as well as continuing to examine the impact of PYL over a longer follow-up time period. This research provides further longitudinal evidence that PlanYourLifespan. org continues to be an effective patient-centered tool for planning for aging-in-place and long-term care needs.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported through a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Award (IH-12-11-4259).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer

Publisher's Disclaimer: All statements, including findings and conclusions, are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), its Board of Governors or Methodology Committee.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics Review

The Northwestern University Institutional Review Board approved this study (STU00080333).

References

- Avery E, Kleppinger A, Feinn R, & Kenny AM (2010). Determinants of living situation in a population of community-dwelling and assisted living-dwelling elders. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 11(2), 140–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball MM, Perkins MM, Whittington FJ, Connell BR, Hollingsworth C, King SV, Elrod CL, & Combs BL (2004). Managing decline in assisted living: The key to aging in place. Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences & Social Sciences, 59, S202–S212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control. (2020). Health places terminology. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyplaces/terminology.htm

- Gillsjo C, Schwartz-Barcott D, & von Post I (2011). Home: The place older adults cannot imagine living without. BMC Geriatrics, 11, Article 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindquist LA, Ramirez-Zohfeld V, Sunkara PD, Forcucci C, Campbell D, Mitzen P, & Cameron KA (2016). Advanced Life Events (ALEs) that impede aging-in-place among seniors. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 64, 90–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindquist LA, Ramirez-Zohfeld V, Sunkara PD, Forcucci C, Campbell DS, Mitzen P, Kricke G, & Cameron KA (2017). PlanYourLifeSpan.org—An intervention to help seniors make choices for their fourth-quarter of life: Results from the randomized clinical trial. Patient Education and Counseling, 100(11), 1996–2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindquist LA, Ramirez-Zohfeld V, Sunkara PD, Forcucci C, Campbell DS, Mitzen P, Kricke G, Seltzer A, Ramirez AV, & Cameron KA (2017). Helping seniors plan for posthospital discharge needs before a hospitalization occurs: Results from randomized control trial of planyourlifespan.org. Journal of Hospital Medicine, 12(11), 911–917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Zohfeld V, Cameron KA, Sunkara P, Forcucci C, Huisingh-Scheetz M, & Lindquist LA (2016). Fear of independence loss (FOIL): Older adult perceptions on refusal of home care. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 29, S97–S98. [Google Scholar]

- Seplaki CL, Agree EM, Weiss CO, Szanton SL, Bandeen-Roche K, & Fried LP (2014). Assistive devices in context: Cross-sectional association between challenges in the home environment and use of assistive devices for mobility. Gerontologist, 54, 651–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang F, & Lee Y (2010). Home- and community-based services utilization and aging in place. Home Health Care Services Quarterly, 29, 138–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yondorf B (2005). Aging in place: State policy trends and options. National Conference State Legislatures. [Google Scholar]