Summary

Background

National investigations on age-specific modifiable risk factor profiles for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and mortality are scarce in China, the country that is experiencing a huge cardiometabolic burden exacerbated by population ageing.

Methods

This is a nationwide prospective cohort study of 193,846 adults in the China Cardiometabolic Disease and Cancer Cohort Study, 2011-2016. Among 139,925 participants free from CVD at baseline, we examined hazard ratios and population-attributable risk percentages (PAR%s) for CVD and all-cause mortality attributable to 12 modifiable socioeconomic, psychosocial, lifestyle, and metabolic risk factors by four age groups (40-<55 years, 55-<65 years, 65-<75 years, and ≥75 years).

Findings

Metabolic risk factors accounted for 52·4%, 47·2%, and 37·8% of the PAR% for CVD events in participants aged 40-<55 years, 55-<65 years, and 65-<75 years, respectively, with hypertension being the largest risk factor. While in participants aged ≥75 years, lifestyle risk factors contributed to 34·0% of the PAR% for CVD, with inappropriate sleep duration being the predominant risk factor. Most deaths were attributed to metabolic risk factors (PAR% 25·3%) and lifestyle risk factors (PAR% 24·6%) in participants aged 40-<55 years, with unhealthy diet and diabetes being the main risk factors. While in participants aged ≥55 years, most deaths were attributed to lifestyle risk factors (PAR% 26·6%-41·0%) and socioeconomic and psychosocial risk factors (PAR% 26·1%-27·7%). In participants aged ≥75 years, lifestyle risk factors accounted for 41·0% of the PAR% for mortality, with inappropriate sleep duration being the leading risk factor.

Interpretation

We identified age-specific modifiable risk profiles for CVD and all-cause mortality in Chinese adults, with remarkable differences between adults aged ≥75 years and their younger counterparts.

Funding

National Natural Science Foundation of China.

Keywords: Age-specific risk profile, Modifiable risk factor, Cardiovascular disease, All-cause mortality

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

We searched PubMed for studies published until July 30, 2021, using the key terms “risk factor”, “Asians” (or “China”), and “cardiovascular” (or “mortality”), in combination with “age” or “elderly” or “older”. We also searched references listed in the identified papers. Previous studies, mainly from general population younger than 75 years, have associated several modifiable risk factors with increased risks of cardiovascular disease (CVD) or mortality. Because of the age-related alterations in cardiovascular structure and function, coupled with changes in lifestyle and metabolic status, the generalization of current evidence from younger adults may not be applicable to older adults. Therefore, identifying unique risk factor profiles for people of different age groups including population aged 75 years and older will help promote individualized management strategies to reduce the risk of CVD and mortality, which is imperative for countries like China that are experiencing great cardiometabolic burdens and unprecedented population ageing.

Added value of this study

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first and largest nationwide study to elucidate age-related disparities in the risks of CVD and all-cause mortality attributable to 12 modifiable socioeconomic, psychosocial, lifestyle, and metabolic risk factors in Chinese adults. In participants aged <75 years, metabolic factors accounted for 37·8% to 52·4% of CVD events, with hypertension being the largest risk factor. While in adults aged ≥75 years, lifestyle factors accounted for 34·0% of CVD events, and inappropriate sleep duration was the predominant risk factor. Age-specific risk factor profiles were also identified for all-cause mortality, with metabolic factors (PAR% 25·3%) and lifestyle factors (PAR% 24·6%) being the main risk factors in participants aged 40-<55 years and lifestyle factors (PAR% 26·6%-41·0%) and socioeconomic and psychosocial factors (PAR% 26·1%-27·7%) contributing the major PAR% in participants aged ≥55 years.

Implications of all the available evidence

Our findings highlight the importance of prioritizing age-specific risk profiles for precise and efficient prevention and control of CVD and mortality for countries like China that are encountering formidable health challenges and population ageing.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

Introduction

Globally, there were an estimated 485·6 million cases of cardiovascular disease (CVD), with the majority of CVD and deaths occurring in adults aged 75 years and older.[1,2] In China, CVD is the leading cause of mortality, accounting for more than 40% of deaths.[3,4] China has the largest older population (65 years and older) in the world, and the rapid and consistent increase in the ageing population has brought huge challenges to the prevention and control of CVD.[5,6] The Global Burden of Disease Study and the Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology Study have provided global estimates of the effect of multiple modifiable risk factors, individually or collectively, on CVD or mortality.[7,8] However, thorough data linking risk factors with CVD and mortality have been mostly derived from people younger than 75 years,[2,8] and uncertainty exists with regard to the consistency or variation in the impact of modifiable risk factors on CVD and mortality by different age groups. Importantly, age-related alterations in cardiometabolic functions and lifestyle behaviors may translate into different susceptibilities to CVD and mortality between older people and their younger counterparts.[2,5] Therefore, identifying unique risk factor profiles for people of different age groups including populations aged 75 years and older will help promote individualized management strategies to reduce the risk of CVD and mortality, which is imperative for countries like China that are experiencing great cardiometabolic burdens exacerbated by unprecedented population ageing.[9]

To this end, we quantified and compared the associations and population-attributable risks of common modifiable socioeconomic, psychosocial, lifestyle, and metabolic risk factors with the risks of CVD and all-cause mortality among adults of different age groups, with the group of adults aged 75 years and older as a significant population of interest.

Methods

Study design and participants

The China Cardiometabolic Disease and Cancer Cohort (4C) Study is a multicenter, population-based, prospective cohort study.[10,11] The baseline survey was conducted between 2011 and 2012, and 193,846 men and women aged 40 years and older were recruited from local resident registration systems of 20 communities from various geographic regions in China to represent the general population. Briefly, 20 communities were selected according to geographic region (Northeast, North, East, South Central, Northwest, and Southwest China), degree of urbanization (large and midsize cities, county seats, and rural townships), and economic development status (by gross domestic product of each province). Eligible men and women aged 40 years and older were identified from local resident registration systems. Trained community health workers visited eligible individuals’ homes and invited them to participate in the study. Those who agreed to participate and signed the informed consent were scheduled for a personal interview and a clinic visit within a week after the recruitment. The follow-up survey was conducted between 2014 and 2016, and 170,240 participants (87·8%) attended an in-person follow-up visit. Of 170,240 participants with follow-up data available, we excluded 11,590 participants with CVD at baseline and 18,725 participants with missing data on risk factors or covariates. Thus, 139,925 participants were included in the analysis for all-cause mortality. We further excluded 20,470 participants whose information on the ascertainment of CVD during follow-up was not available, and 119,455 participants were included in the analysis for CVD events (flowchart of study participants see Supplementary Figure 1). Baseline key characteristics of the study participants and those who were excluded from the analysis due to missing values of risk factors or covariates were similar. This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Ruijin Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University. All study participants provided written informed consent.

Data collection

At baseline and follow-up visits, data collection was performed in local community clinics by trained study personnel following standardized protocols. Standardized questionnaires were used to collect information on demographic characteristics, educational attainment, and lifestyle factors (smoking and drinking status and sleep duration). The 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire was applied to evaluate depression severity, and a score was calculated to make criteria-based diagnoses of depression.[12,13] The International Physical Activity Questionnaire was used to assess physical activity,[14] and metabolic equivalent was calculated to evaluate average weekly energy expenditure.[15] A validated food frequency questionnaire was used to collect habitual dietary intake by asking the consumption frequency and portion size of typical food items during the previous 12 months.[16] A healthy diet score was calculated on the basis of five healthy dietary behaviors: high consumptions of fruits and vegetables (≥4·5 cups/day), fish (≥two 3·5-oz servings/week), cereal grains (≥three 1-oz serving/day), and soy food (soy protein ≥25 g/day); low consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages (≤450 kcal/week). Each dietary behavior was scored as 1 for healthy and 0 otherwise, and individual component scores were summed to obtain a healthy diet score ranging from 0 to 5 points, with a higher score indicating a healthier diet. The food frequency questionnaire also collected alcohol intake including red wine, white wine, beer, and liquor. We multiplied the amount of alcohol in grams per specified portion size by consumption frequency per day, and summed all types of alcohol to estimate the total alcohol intake (g/day).

Height, body weight, and waist circumference were measured, and body mass index was calculated as body weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters. Three measurements of systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure obtained by an automated electronic device (OMRON Model HEM-752 FUZZY, Dalian, China) in a seated position after at least a 5-minute quiet rest were averaged for analysis.

All participants underwent a 2-hour, 75-gram oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) after an overnight fast of at least 10 hours, and blood samples were collected at 0 and 2 hours during the test. Fasting and 2-hour plasma glucose concentrations were measured locally using a glucose oxidase or hexokinase method within 2-hour after blood sample collection. Finger capillary whole blood samples were collected by the Hemoglobin Capillary Collection System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) and were shipped and stored at 2°C to 8°C until glycated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) was measured within 4-week after collection by high-performance liquid chromatography using the VARIANT II Hemoglobin Testing System (Bio-Rad Laboratories) at the central laboratory in the Shanghai Institute of Endocrine and Metabolic Diseases, which is certificated by the U.S. National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program and passed the Laboratory Accreditation Program of the College of American Pathologists.[10] Serum low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglycerides, total cholesterol, and creatinine were measured at the central laboratory using an auto-analyzer (ARCHITECT ci16200, Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, IL, USA). Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation.[17]

Definition of risk factors

We selected 12 common modifiable risk factors, including socioeconomic and psychosocial factors (low education and depression), lifestyle factors (smoking, high alcohol intake, physical inactivity, unhealthy diet, and inappropriate sleep duration), and metabolic factors (obesity, diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and chronic kidney disease [CKD]), based on the selection criteria: (1) compelling evidence, including but not limited to studies of Chinese population, was available on the presence and magnitude of their associations with CVD and mortality; (2) high likelihood of causality existed based on collective scientific knowledge; (3) they were relatively prevalent and had essential public health impacts; (4) they were potentially modifiable; and (5) data on risk factor exposure were available in the 4C Study. The selection rationale and definition of risk factors are presented in Supplementary Methods 1 and Supplementary Methods 2. We defined all individual risk factors as binary variables (risk and non-risk categories), with the risk category having the potential to be modified or improved towards a healthier direction. Regarding alcohol intake, moderate intake (5-15 g/day for women and 5-30 g/day for men) has been consistently associated with cardiovascular benefits in large cohort studies, but the associations between alcohol intake and some specific diseases such as cancers are in dose-response manners.[18] As current guidelines do not encourage a non-alcohol drinker to start drinking alcohol just for cardiovascular benefits, we combined moderate alcohol intake and none or low alcohol intake as a non-risk factor and defined high alcohol intake as a risk factor.

Ascertainment of cardiovascular events and mortality

CVD events were the composite of incident nonfatal or fatal CVD, including myocardial infarction, stroke, hospitalized or treated heart failure, and cardiovascular death. Myocardial infarction was defined as characteristic changes in troponin T and creatine-kinase-MB isoform levels, symptoms of myocardial ischemia, changes in electrocardiogram results, or a combination of them. Stroke was defined as a fixed neurological deficit at least 24 hours because of a presumed vascular cause. Heart failure was identified by hospitalization or an emergency department visit requiring treatment with infusion therapy and was defined as a clinical syndrome presenting with multiple signs and symptoms consistent with cardiac decompensation or inadequate cardiac pump function. Information on deaths and clinical outcomes were collected from local death registries of the National Disease Surveillance Point System and National Health Insurance System. The clinical outcome adjudication committee is composed of 10 blinded, unbiased experts in oncology, cardiology, neurology, and endocrine and metabolic diseases. Two members of the outcome adjudication committee independently verified each clinical event and assigned potential causes of death according to a standard clinical outcome adjudication procedure. Discrepancies were adjudicated by discussions involving other members of the committee.

Statistical analysis

Participants were divided into four age groups: 40-<55 years, 55-<65 years, 65-<75 years, and ≥75 years. Baseline characteristics were summarized as means with standard deviations (SDs) for continuous variables or numbers with percentages for categorical variables. Differences of characteristics between age groups were examined by one-way analysis of variance for continuous variables or Chi-square test for categorical variables.

Cox proportional hazards models were used to calculate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for CVD events and all-cause mortality associated with risk factors by age groups. Models were adjusted for sex, and individual risk factors were mutually adjusted. In the time-to-event analysis for CVD events, participants were censored at the date of CVD diagnosis, death, or the end of follow-up (Dec 31, 2016), whichever occurred first. In the time-to-event analysis for mortality, participants were censored at the date of death or the end of follow-up (Dec 31, 2016), whichever occurred first. Person-time was calculated from the enrollment date to the censoring date for each participant. We investigated multiplicative interactions of age with risk factors by including the product term in models to evaluate the variations in the associations of risk factors with CVD and mortality across different age groups.

We calculated the population-attributable risk percentage (PAR%) to assess the population-level risks of CVD and all-cause mortality attributable to risk factors following a well-developed method,[19,20] with adjustment for the same set of variables as the HR calculation (Supplementary Methods 3). The PAR% is an estimate of the proportion of incident cases in the study population during follow-up that hypothetically would have been avoided if no one in the population were exposed to specific risk factor(s).[19] Individual risk factor with a negative PAR% was not included in the models; the negative PAR% was truncated at a lower limit of 0, as this is the lowest threshold to determine an association with increased risk.[8]

HRs and PAR%s for CVD and mortality associated with individual and combination of risk factors also were analyzed in the overall participants, with additional adjustment for age. We did three further sensitivity analyses. First, we replicated age stratification analyses in men and women separately and added a three-way interaction between sex, age group, and risk factors of interest to the models to examine whether age-related variations in these associations differed by sex. Second, we analyzed associations of individual risk factors with CVD events and mortality by age groups of 40-<50 years, 50-<60 years, 60-<70 years, and ≥70 years to evaluate the stability of age-specific risk factor profiles for CVD and mortality. Third, we repeated age stratification analyses for different components of dyslipidemia. Statistical significance was assessed using a two-sided P value of <0·05. Statistical analyses were carried out using SAS software, version 9·4 (SAS Institute Inc).

Role of the funding source

The funding source had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or manuscript preparation. The corresponding authors had full access to all data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

Baseline characteristics of participants

The mean (SD) age of 139,925 participants was 56·4 (9·0) years, and 47,476 (33·9%) were men (Table 1). Compared with participants aged 40-<55 years, older participants had higher proportions of men; had lower educational attainment, lower severity of depression, and lower proportions of a healthy diet; were less likely to smoke or drink alcohol; were more likely to be physically active and have inappropriate sleep duration; and had poorer metabolic profiles including obesity, diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and CKD. During 3·8 years’ mean follow-up, we identified 2,975 CVD events (481 myocardial infarction, 1,688 stroke, 240 heart failure, and 638 cardiovascular deaths) and 2,154 all-cause mortality.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study participants by age groups

| Characteristic | Overall | Age group |

P value* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40-<55 years | 55-<65 years | 65-<75 years | ≥75 years | |||

| Number of participants | 139925 | 63053 | 52517 | 20854 | 3501 | |

| Age, year | 56·4 (9·0) | 48·5 (4·3) | 59·4 (2·8) | 69·1 (2·8) | 78·3 (3·3) | <0·001 |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||||

| Men | 47476 (33·9) | 18923 (30·0) | 18574 (35·4) | 8405 (40·3) | 1574 (45·0) | <0·001 |

| Women | 92449 (66·1) | 44130 (70·0) | 33943 (64·6) | 12449 (59·7) | 1927 (55·0) | |

| Socioeconomic and psychosocial factor | ||||||

| Education, n (%) | ||||||

| High school or further | 52280 (37·4) | 30067 (47·7) | 15492 (29·5) | 6019 (28·9) | 702 (20·1) | <0·001 |

| Less than high school | 87645 (62·6) | 32986 (52·3) | 37025 (70·5) | 14835 (71·1) | 2799 (80·0) | |

| Depression severity, n (%) | ||||||

| Minimal | 131773 (94·2) | 59278 (94·0) | 49454 (94·2) | 19698 (94·5) | 3343 (95·5) | <0·001 |

| Mild or greater | 8152 (5·8) | 3775 (6·0) | 3063 (5·8) | 1156 (5·5) | 158 (4·5) | |

| Lifestyle factor | ||||||

| Smoking, n (%) | ||||||

| Never | 113035 (80·8) | 51581 (81·8) | 41726 (79·5) | 16847 (80·8) | 2881 (82·3) | <0·001 |

| Former | 6608 (4·7) | 1962 (3·1) | 2899 (5·5) | 1490 (7·1) | 257 (7·3) | |

| Current | 20282 (14·5) | 9510 (15·1) | 7892 (15·0) | 2517 (12·1) | 363 (10·4) | |

| Alcohol intake, n (%) | ||||||

| None or low | 123074 (88·0) | 55607 (88·2) | 45898 (87·4) | 18444 (88·4) | 3125 (89·3) | <0·001 |

| Moderate | 3460 (2·5) | 1631 (2·6) | 1232 (2·4) | 514 (2·5) | 83 (2·4) | |

| High | 13391 (9·6) | 5815 (9·2) | 5387 (10·3) | 1896 (9·1) | 293 (8·4) | |

| Physical activity, n (%) | ||||||

| Active | 90726 (64·8) | 37105 (58·9) | 35826 (68·2) | 15309 (73·4) | 2486 (71·0) | <0·001 |

| Insufficiently active | 45392 (32·4) | 24171 (38·3) | 15306 (29·1) | 5004 (24·0) | 911 (26·0) | |

| Inactive | 3807 (2·7) | 1777 (2·8) | 1385 (2·6) | 541 (2·6) | 104 (3·0) | |

| Healthy diet score, n (%) | ||||||

| 0-3 | 118064 (84·4) | 52237 (82·9) | 44407 (84·6) | 18281 (87·7) | 3139 (89·7) | <0·001 |

| 4-5 | 21861 (15·6) | 10816 (17·2) | 8110 (15·4) | 2573 (12·3) | 362 (10·3) | |

| Sleep duration, n (%) | ||||||

| <6 hours/day | 13358 (9·6) | 5532 (8·8) | 5306 (10·1) | 2132 (10·2) | 388 (11·1) | <0·001 |

| 6-8 hours/day | 84936 (60·7) | 39016 (61·9) | 32265 (61·4) | 11914 (57·1) | 1741 (49·7) | |

| >8 hours/day | 41631 (29·8) | 18505 (29·4) | 14946 (28·5) | 6808 (32·7) | 1372 (39·2) | |

| Metabolic factor | ||||||

| Obesity, n (%) | 20932 (15·0) | 8985 (14·3) | 8067 (15·4) | 3354 (16·1) | 526 (15·0) | <0·001 |

| Obesity measurement | ||||||

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 24·6 (3·6) | 24·5 (3·6) | 24·7 (3·6) | 24·7 (3·7) | 24·2 (3·9) | <0·001 |

| Waist circumference, cm | 84·2 (9·9) | 82·7 (9·6) | 84·9 (9·8) | 86·3 (10·1) | 86·4 (10·6) | <0·001 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 32325 (23·1) | 9922 (15·7) | 13929 (26·5) | 7267 (34·9) | 1207 (34·5) | <0·001 |

| Glucose profile | ||||||

| Fasting glucose, mg/dL | 107·6 (29·5) | 104·2 (27·7) | 109·5 (30·3) | 112·4 (31·1) | 111·0 (31·8) | <0·001 |

| OGTT-2h glucose, mg/dL | 147·9 (68·1) | 135·7 (60·2) | 153·4 (70·7) | 167·4 (75·5) | 167·5 (74·1) | <0·001 |

| HbA1c, % | 6·0 (1·0) | 5·8 (0·9) | 6·1 (1·1) | 6·2 (1·1) | 6·2 (1·1) | <0·001 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 59402 (42·5) | 18627 (29·5) | 25272 (48·1) | 13095 (62·8) | 2408 (68·8) | <0·001 |

| Blood pressure | ||||||

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 132·3 (20·5) | 126·4 (18·3) | 134·9 (20·3) | 141·7 (21·1) | 146·4 (22·8) | <0·001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 78·2 (11·1) | 77·9 (11·2) | 79·0 (10·9) | 77·3 (11·0) | 74·8 (11·4) | <0·001 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 59216 (42·3) | 24580 (39·0) | 23854 (45·4) | 9332 (44·8) | 1450 (41·4) | <0·001 |

| Lipid profile | ||||||

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 111·0 (33·8) | 107·2 (33·1) | 114·3 (34·0) | 113·7 (34·0) | 114·3 (34·1) | <0·001 |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 51·9 (14·1) | 51·7 (14·1) | 52·0 (14·1) | 51·8 (14·2) | 52·8 (14·4) | <0·001 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 144·4 (109·0) | 140·7 (113·0) | 150·4 (109·7) | 143·4 (98·1) | 128·9 (78·8) | 0·001 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 191·6 (44·0) | 186·3 (43·6) | 196·3 (43·8) | 195·1 (44·0) | 195·3 (43·8) | <0·001 |

| CKD, n (%) | 2913 (2·1) | 342 (0·5) | 907 (1·7) | 1187 (5·7) | 477 (13·6) | <0·001 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1·73m2 | 94·1 (13·5) | 101·1 (11·0) | 91·3 (11·3) | 83·2 (12·5) | 75·6 (13·9) | <0·001 |

Values are mean (SD) or n (%). Percentages may not sum to 100% because of rounding. SI conversion factors: To convert fasting and OGTT-2h plasma glucose to mmol/L, multiply by 0·0555; HbA1c to proportion of total hemoglobin, multiply by 0·01; LDL, HDL, and total cholesterol to mmol/L, multiply by 0·0259; and triglycerides to mmol/L, multiply by 0·0113.

*P values are based on one-way analysis of variance for continuous variables or Chi-square test for categorical variables.

Abbreviations: CKD=chronic kidney disease; eGFR=estimated glomerular filtration rate; HbA1c=hemoglobin A1c; HDL=high-density lipoprotein; LDL=low-density lipoprotein; OGTT=oral glucose tolerance test.

Associations of risk factors with CVD and all-cause mortality by age groups

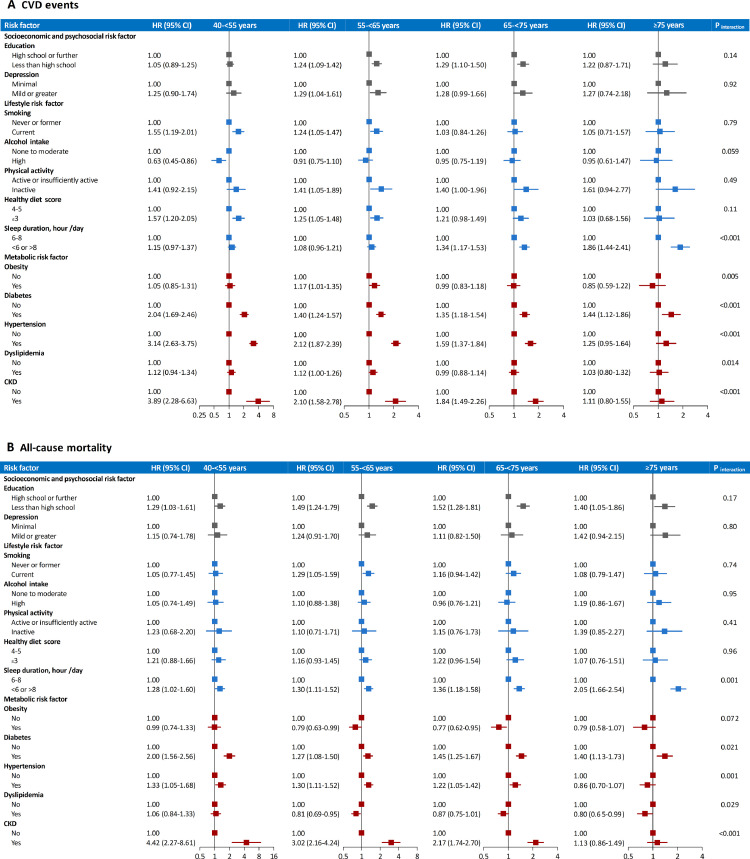

In the overall participants, the strongest risk factor associated with CVD was hypertension, followed by CKD, diabetes, physical inactivity, depression, unhealthy diet, low education, smoking, inappropriate sleep duration, and dyslipidemia (Supplementary Table 1). When stratified by age, multivariable-adjusted HR (95% CI) of CVD associated with inappropriate sleep duration was increased from 1·15 (0·97-1·37) in participants aged 40-<55 years to 1·86 (1·44-2·41) in participants aged ≥75 years (P[interaction]<0·001; Figure 1A). By contrast, CVD risks associated with several metabolic risk factors were diminished with age. In participants aged 40-<55 years, the HR (95% CI) of CVD was 2·04 (1·69-2·46) for diabetes, 3·14 (2·63-3·75) for hypertension, and 3·89 (2·28-6·63) for CKD; while in participants aged ≥75 years, the corresponding HRs (95% CIs) were 1·44 (1·12-1·86), 1·25 (0·95-1·64), and 1·11 (0·80-1·55), respectively (all P[interaction]<0·001). Similar but weaker interaction patterns were observed for obesity (P[interaction]=0·005) and dyslipidemia (P[interaction]=0·014). The borderline association between dyslipidemia and CVD among participants aged 55-<65 years might be driven by the effects of high low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and high total cholesterol (Supplementary Table 2). There were no substantial age-related variations in associations between other risk factors and CVD.

Figure 1.

Hazard ratio (95% CI) of CVD events and all-cause mortality associated with individual risk factors by age groups

A. CVD events; B. all-cause mortality. Models were adjusted for sex, and individual risk factors were mutually adjusted. P values for interaction between age group and each individual risk factor are for testing the variations in the associations of each individual risk factor with CVD events or all-cause mortality across different age groups. Abbreviations: CI=confidence interval; CKD=chronic kidney disease; CVD=cardiovascular disease; HR=hazard ratio.

Overall, the strongest risk factor for mortality was CKD, followed by low education, inappropriate sleep duration, diabetes, smoking, unhealthy diet, and hypertension (Supplementary Table 1). Of lifestyle factors, the association between inappropriate sleep duration and mortality was strengthened with age (40-<55 years: HR 1·28, 95% CI 1·02-1·60; ≥75 years: HR 2·05, 95% CI 1·66-2·54; P[interaction]=0·001; Figure 1B). Of metabolic factors, the HR (95% CI) of mortality associated with CKD was 4·42 (2·27-8·61) in participants aged 40-<55 years and 1·13 (0·86-1·49) in participants aged ≥75 years (P[interaction]<0·001). Diabetes (P[interaction]=0·021) and hypertension (P[interaction]=0·001) exhibited similar interaction patterns with age on mortality. The associations between different components of dyslipidemia and mortality were consistent with the main association between dyslipidemia and mortality across age groups (Supplementary Table 3). Other risk factors showed consistent associations with mortality by age groups.

Generally, the age-related variations in associations of risk factors with CVD events and all-cause mortality were similar between men and women, except that the age-related decrease in association between dyslipidemia and CVD (P for three-way interaction=0·034) was prominent in women but not in men (Supplementary Table 4), and the age-related increases in associations of low education (P for three-way interaction=0·032) and physical inactivity (P for three-way interaction=0·039) with mortality were prominent in women but not in men (Supplementary Table 5).

The original age-related association patterns of risk factors with CVD events and all-cause mortality were replicated by using age groups of 40-<50 years, 50-<60 years, 60-<70 years, and ≥70 years (Supplementary Table 6 and Supplementary Table 7).

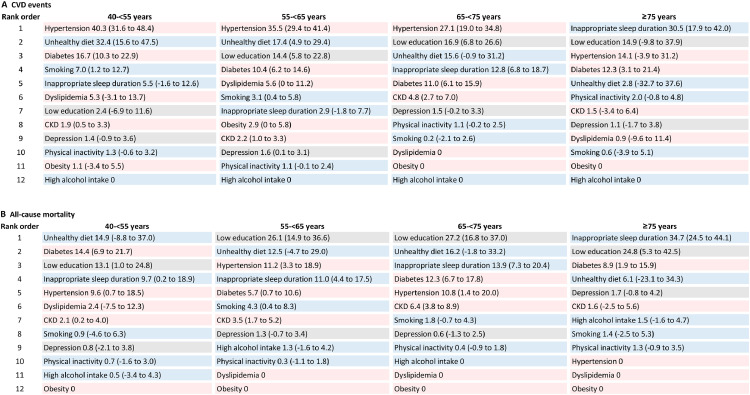

PAR%s for CVD and all-cause mortality associated with risk factors by age groups

Hypertension was the single largest risk factor (PAR% 30·7%, 95% CI 26·7%-34·7%) for CVD in the overall participants (Supplementary Table 8) and in participants aged 40-<75 years, accounting for 40·3% (95% CI 31·6%-48·4%), 35·5% (95% CI 29·4%-41·4%), and 27·1% (95% CI 19·0%-34·8%) of the PAR% in age groups of 40-<55 years, 55-<65 years, and 65-<75 years, respectively (Figure 2A). Unhealthy diet, diabetes, low education, and inappropriate sleep duration each contributed more than 10% of the PAR% in at least one age group of <75 years. In participants aged ≥75 years, inappropriate sleep duration was the largest risk factor for CVD (PAR% 30·5%, 95% CI 17·9%-42·0%); low education, hypertension, and diabetes also accounted for considerable proportions of the PAR% (12·3%-14·9%).

Figure 2.

Population-attributable risk percentage (95% CI) for CVD events and all-cause mortality associated with individual risk factors by age groups

A. CVD events; B. all-cause mortality. Models were adjusted for sex, and individual risk factors were mutually adjusted. Individual risk factors with a negative PAR% were not included in analyses; the negative PAR% was truncated at a lower limit of 0, as this is the lowest threshold to determine an association with increased risk. Grey box indicates socioeconomic and psychosocial risk factor, blue box indicates lifestyle risk factor, and pink box indicates metabolic risk factor. Abbreviations: CKD=chronic kidney disease; CVD=cardiovascular disease.

For mortality, the largest risk factor was low education (PAR% 22·0%, 95% CI 16·0%-27·7%) in the overall participants (Supplementary Table 8). In participants aged 40-<55 years, unhealthy diet, diabetes, and low education were the top three risk factors accounting for comparable PAR%s (13·1%-14·9%) for mortality (Figure 2B). The largest PAR% for mortality was attributed to low education in participants aged 55-<75 years (PAR% 26·1%-27·2%) and inappropriate sleep duration in participants aged ≥75 years (PAR% 34·7%, 95% CI 24·5%-44·1%).

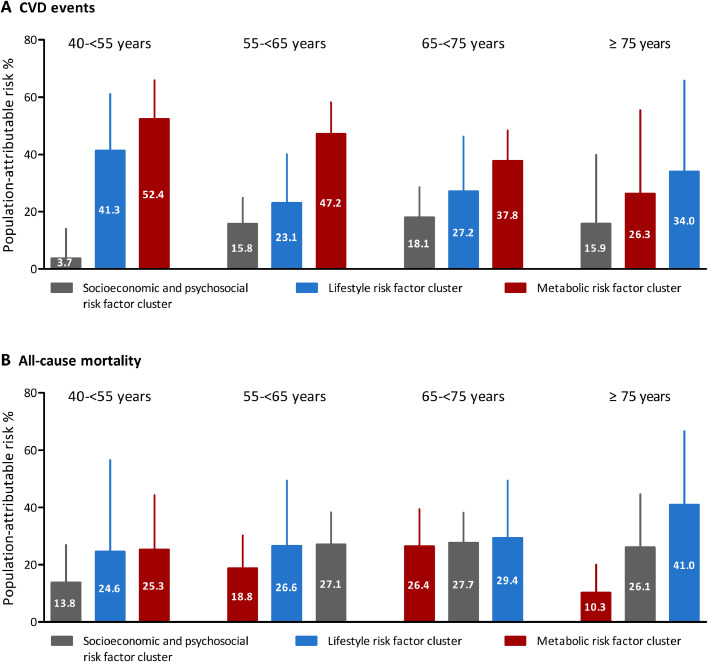

Collectively, metabolic risk factors accounted for 40.8% (95% CI 32·5%-48·5%) of the PAR% for CVD in the overall participants, followed by lifestyle risk factors (PAR% 27·9%, 95% CI 16·4%-38·7%) and socioeconomic and psychosocial risk factors (PAR% 14·0%, 95% CI 8·3%-19·5%; Supplementary Table 8). In participants younger than 75 years, the largest PAR% for CVD was attributed to the combination of metabolic factors, accounting for 52·4% (95% CI 35·6%-65·9%), 47·2% (95% CI 34·6%-58·2%), and 37·8% (95% CI 26·2%-48·4%) in age groups of 40-<55 years, 55-<65 years, and 65-<75 years, respectively (Figure 3A). In participants aged ≥75 years, the combination of lifestyle factors contributed to the largest PAR% (34·0%, 95% CI 1.2%-65.8%) for CVD.

Figure. 3.

Population-attributable risk percentage (95% CI) for CVD events and all-cause mortality associated with combinations of risk factors by age groups

CVD events; B. all-cause mortality. Models were adjusted for sex, and individual risk factors were mutually adjusted. Individual risk factors with a negative PAR% were not included in analyses; the negative PAR% was truncated at a lower limit of 0, as this is the lowest threshold to determine an association with increased risk. Abbreviations: CVD=cardiovascular disease.

Overall, lifestyle risk factors contributed to 29·3% (95% CI 14·8%-42·5%) of the PAR% for mortality, followed by socioeconomic and psychosocial risk factors (PAR% 22·8%, 95% CI 16·3%-29·1%) and metabolic risk factors (PAR% 14·1%, 95% CI 7·7%-20·3%; Supplementary Table 8). In participants aged 40-<55 years, metabolic factors and lifestyle factors accounted for most deaths with comparable PAR%s (25·3%-24·6%; Figure 3B). While in participants aged 55-<75 years, most deaths were attributed to lifestyle factors (PAR% 26·6%-29·4%) and socioeconomic and psychosocial factors (PAR% 27·1%-27·7%). Especially in participants aged ≥75 years, lifestyle factors accounted for the largest PAR% for mortality (PAR% 41·0%, 95% CI 6·9%-66·6%), followed by socioeconomic and psychosocial factors (PAR% 26·1%, 95% CI 5·5%-44·6%) and metabolic factors (PAR% 10·3%, 95% CI 0·4%-20·0%).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first and largest nationwide study elucidating age-specific modifiable risk factor profiles for CVD events and mortality in middle-aged and older Chinese population. In adults younger than 75 years, metabolic risk factors accounted for 37·8% to 52·4% of CVD cases, with hypertension being the leading risk factor. While in adults aged ≥75 years, lifestyle risk factors contributed to 34·0% of CVD cases, with inappropriate sleep duration being the predominant risk factor. Regarding all-cause mortality, in adults aged 40-<55 years, most deaths were attributed to metabolic risk factors (PAR% 25·3%) and lifestyle risk factors (PAR% 24·6%); the main risk factors were unhealthy diet, diabetes, and low education, with each accounting for over 10% of deaths. Lifestyle risk factors (PAR% 26·6%-41·0%) and socioeconomic and psychosocial risk factors (PAR% 26·1%-27·7%) were main contributors to mortality in adults aged 55 years and older. Especially in adults aged ≥75 years, inappropriate sleep duration and low education contributed to 34·7% and 24·8% of the PAR% for deaths, respectively. Several specific risk factors showed significant interactions with age: inappropriate sleep duration associated with greater hazards of CVD and mortality in older adults, while hypertension, diabetes, and CKD associated with greater hazards of CVD and mortality in younger adults.

Principal findings and comparison with other studies

Our findings in general population are in line with the Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology Study of adults aged 35-70 years that most CVD cases and deaths were attributed to metabolic risk factors and lifestyle risk factors, respectively.[8] By including population aged 75 years and older and from an age stratification perspective, we further elaborated on the heterogeneity of risk factor profiles for CVD and mortality in adults of different age groups, particularly emphasizing the importance of metabolic risk factors for younger adults and lifestyle risk factors for older adults in predicting, preventing and controlling of CVD and mortality.

The observed age-related risk factor profiles for CVD and mortality were largely driven by several specific risk factors. In this study, we identified hypertension and diabetes as leading metabolic risk factors for CVD and mortality in adults younger than 75 years. Hypertension and diabetes have been strongly associated with CVD and mortality,[7,8,21] and the prevalence of these two risk factors has reached an alarming level in China.[22,23] Moreover, although CKD contributed to modest PAR% for CVD and mortality due to its relatively low prevalence, CKD manifested the strongest association with CVD and mortality in adults younger than 75 years, in accordance with previous evidence that CKD was a robust risk factor for CVD and mortality, independent of conventional risk factors such as hypertension and diabetes.[24] The interaction findings that the excess risks of CVD and mortality associated with hypertension, diabetes, and CKD were diminished with age are intriguing. Previous studies also revealed a weak effect of blood pressures on CVD in population aged 65 years and older.[25,26] Potential explanations to these observations may be that metabolic disorders such as hypertension and diabetes are more strongly related to cardiovascular complications (stroke and coronary heart disease) which occur earlier than other cardiovascular consequences,[27] and the risks of CVD and all-cause mortality are especially prominent in younger-onset metabolic diseases.[28] Furthermore, the age-related decreases in the impact of metabolic factors could be partially influenced by selective survival, that is, persons who were more vulnerable to morbidities related to certain risk factors were less likely to survive into older age. However, we also observed age-related increases in the prevalence of these metabolic factors, as well as the amplified or consistent associations between other risk factors (e.g., low education and inappropriate sleep duration) and the outcomes according to age, indicating that selective survival is not the only explanation.

In addition to other widely researched lifestyle factors, emerging large longitudinal studies and meta-analyses have implicated that compared with sleeping 6-8 hours/day, both longer and shorter sleeping exhibited excess risks of major CVD and all-cause mortality.[29,30] A large prospective study also reported that the U-shaped association between sleep duration (shorter or longer versus 6-8 hours/day) and CVD was more prominent in older adults than in younger adults (cutoff at age 65 years).[31] Our study extended previous findings by providing new evidence that of all investigated modifiable risk factors, inappropriate sleep duration conferred the leading burden of CVD and mortality in adults aged 75 years and older.

In this study, the impact of low education on mortality and CVD persisted in middle-aged to older adults. Low education has been documented as a robust socioeconomic determinant to be most clearly associated with CVD and mortality, mainly through its broader influence on unhealthy behaviors and social disadvantages such as poor access to health care and social resources, throughout a person's life.[8,32] Thus, our findings suggest that even in older adults, strategies to improve education and to eliminate the adverse effect of low education are likely to mitigate some of the substantial excess burden of mortality and CVD.

High alcohol intake displayed no excess risk of CVD in all age groups in this study. The Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology Study also identified modest association of alcohol use with CVD, particularly in middle-income countries.[8] Previous cohort studies indicated that alcohol intake was inversely associated with non-fatal coronary heart disease,[33] and compared with moderate alcohol intake, high alcohol intake was associated with no excess risk of coronary heart disease and a lower risk of myocardial infarction.[34] These findings may be due to the considerable heterogeneity of associations with different CVD subtypes.[33,34] Besides, we focused on first-ever CVD events in this study, and therefore it is possible that heavy drinkers had experienced CVD or had initially presented with death before they were able to develop CVD. Additionally, obesity conferred no elevated risk of mortality in our analysis, which may be partly due to the “obesity paradox” phenomenon and the interactions between co-existing factors.[35,36]

Clinical implications

Our study illuminated the remarkable differences in modifiable risk profiles for CVD and mortality according to age, suggesting that the estimates generated from younger people may not apply to older people. The risk factor profiles behind different age strata may reflect varied pathophysiological mechanisms, and understanding these age difference patterns are important for future cardiovascular risk evaluation. Our estimates can be used to identify higher-risk people in different age groups to improve prediction precision for CVD and mortality. More importantly, our findings highlight the importance of formulating tailored, age-specific risk factor management strategies to effectively reduce the burden of CVD and mortality.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study included the large nationwide sample with broad age ranges, the comprehensive assessment of risk factors, and the well-validated definitions of CVD and mortality. Our study has limitations. First, the relatively short follow-up duration may limit the statistical power for CVD events and mortality. Second, although we have carefully controlled all risk factors of interest in the analyses and identified no substantial influence of sex on main findings, bias due to reverse causality or unmeasured confounding may exist. Besides, variables collected by questionnaires (e.g., dietary intake collected by the food frequency questionnaire) may be affected by recall bias. Third, some emerging modifiable environmental factors (e.g., ambient air pollution) were not included in the risk factor profile in this study. Therefore, the ranking order of the contributions of risk factors to CVD or mortality should only be interpreted within the scenario of this study. Fourth, in this study, the risk factors were evaluated only at baseline, and data on incident morbidities and therapies during the follow-up period were not available. Thus, changes in risk factors and incident morbidities, as well as related therapies during follow-up could not be accounted for in our analyses. More follow-ups in the future could provide important dynamic data for investigations on age-specific risk profiles for CVD and mortality.

Conclusions

This nationwide prospective cohort study provided novel insights into age-specific modifiable risk factor profiles for CVD events and all-cause mortality in Chinese adults. Our findings underline the importance of prioritizing age-specific risk profiles for precise and efficient prediction, prevention, and intervention of CVD and mortality in China, the country that is encountering formidable health challenges and population ageing.

Contributors

Conception and design: Drs Tiange Wang, Weiqing Wang, Yufang Bi, Lixin Shi, Jieli Lu, and Guang Ning.

Acquisition or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: Dr Tiange Wang.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Statistical analysis: Drs Tiange Wang and Zhiyun Zhao.

Obtained funding: Drs Tiange Wang, Weiqing Wang, Yufang Bi, Jieli Lu, and Guang Ning.

Supervision: Drs Weiqing Wang, Yufang Bi, Lixin Shi, Jieli Lu, and Guang Ning had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Final approval of the version to be published: All authors.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

Data sharing statement

The individual, de-identified participant data that underline the results reported in this Article (text, tables, figures, and appendices) are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author (Weiqing Wang; wqingw61@163.com) under certain conditions (with the consent of all participating centers and with a signed data access agreement).

Funding

This work was supported by the grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81970706, 82022011, 81730023, 81941017, 82070880), the National Key R&D Program of China (2017YFC1310700, 2018YFC1311800), National Science and Technology Major Project for “Significant New Drugs Development” (2017ZX09304007), the Shanghai Municipal Government (18411951800), the Shanghai Shenkang Hospital Development Center (SHDC12019101), the Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (DLY201801), and the Ruijin Hospital (2018CR002). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.lanwpc.2021.100277.

Contributor Information

Guang Ning, Email: gning@sibs.ac.cn.

Yufang Bi, Email: byf10784@rjh.com.cn.

Lixin Shi, Email: slx1962@medmail.com.cn.

Jieli Lu, Email: jielilu@hotmail.com.

Weiqing Wang, Email: wqingw61@163.com.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.GBD 2017 Causes of Death Collaborators Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392(10159):1736–1788. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32203-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rich MW, Chyun DA, Skolnick AH, et al. Knowledge Gaps in Cardiovascular Care of the Older Adult Population: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, and American Geriatrics Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(20):2419–2440. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou M, Wang H, Zhu J, et al. Cause-specific mortality for 240 causes in China during 1990-2013: a systematic subnational analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2016;387(10015):251–272. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00551-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou M, Wang H, Zeng X, et al. Mortality, morbidity, and risk factors in China and its provinces, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2019;394(10204):1145–1158. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30427-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Madhavan MV, Gersh BJ, Alexander KP, Granger CB, Stone GW. Coronary artery disease in patients ≥80 years of age. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(18):2015–2040. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.12.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; 2015. China country assessment report on ageing and health. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/194271. Accessed Mar 15, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 7.GBD 2019 Risk Factors Collaborators Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396(10258):1223–1249. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30752-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yusuf S, Joseph P, Rangarajan S, et al. Modifiable risk factors, cardiovascular disease, and mortality in 155722 individuals from 21 high-income, middle-income, and low-income countries (PURE): a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10226):795–808. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32008-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao D, Liu J, Wang M, Zhang X, Zhou M. Epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in China: current features and implications. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2019;16(4):203–212. doi: 10.1038/s41569-018-0119-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu J, He J, Li M, et al. Predictive Value of Fasting Glucose, Postload Glucose, and Hemoglobin A1c on Risk of Diabetes and Complications in Chinese Adults. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(8):1539–1548. doi: 10.2337/dc18-1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang T, Lu J, Shi L, et al. Association of insulin resistance and β-cell dysfunction with incident diabetes among adults in China: a nationwide, population-based, prospective cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8(2):115–124. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30425-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jha MK, Qamar A, Vaduganathan M, Charney DS, Murrough JW. Screening and Management of Depression in Patients With Cardiovascular Disease: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(14):1827–1845. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.01.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjöström M, et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35(8):1381–1395. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Leon AS, et al. Compendium of physical activities: classification of energy costs of human physical activities. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1993;25(1):71–80. doi: 10.1249/00005768-199301000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li YP, He YN, Zhai FY, et al. Comparison of assessment of food intakes by using 3 dietary survey methods. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2006;40(4):273–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(9):604–612. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.GBD 2016 Alcohol Collaborators Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2018;392(10152):1015–1035. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31310-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spiegelman D, Hertzmark E, Wand HC. Point and interval estimates of partial population attributable risks in cohort studies: examples and software. Cancer Causes Control. 2007;18(5):571–579. doi: 10.1007/s10552-006-0090-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hertzmark E, Wand H, Spiegelman D. The SAS PAR Macro. 2012. https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/donna-spiegelman/soft ware/par/. Accessed Jul 15, 2021.

- 21.Mahmood SS, Levy D, Vasan RS, Wang TJ. The Framingham Heart Study and the epidemiology of cardiovascular disease: a historical perspective. Lancet. 2014;383(9921):999–1008. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61752-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lu J, Lu Y, Wang X, et al. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in China: data from 1.7 million adults in a population-based screening study (China PEACE Million Persons Project) Lancet. 2017;390(10112):2549–2558. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32478-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li Y, Teng D, Shi X, et al. Prevalence of diabetes recorded in mainland China using 2018 diagnostic criteria from the American Diabetes Association: national cross sectional study. BMJ. 2020;369:m997. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sarnak MJ, Amann K, Bangalore S, et al. Chronic Kidney Disease and Coronary Artery Disease: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74(14):1823–1838. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.08.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tate RB, Manfreda J, Cuddy TE. The effect of age on risk factors for ischemic heart disease: the Manitoba Follow-Up Study, 1948-1993. Ann Epidemiol. 1998;8(7):415–421. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(98)00011-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Casiglia E, Mazza A, Tikhonoff V, et al. Weak effect of hypertension and other classic risk factors in the elderly who have already paid their toll. J Hum Hypertens. 2002;16(1):21–31. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fuchs FD, Whelton PK. High Blood Pressure and Cardiovascular Disease. Hypertension. 2020;75(2):285–292. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.119.14240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao M, Song L, Sun L, et al. Associations of Type 2 Diabetes Onset Age With Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality: The Kailuan Study. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(6):1426–1432. doi: 10.2337/dc20-2375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang C, Bangdiwala SI, Rangarajan S, et al. Association of estimated sleep duration and naps with mortality and cardiovascular events: a study of 116632 people from 21 countries. Eur Heart J. 2019;40(20):1620–1629. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yin J, Jin X, Shan Z, et al. Relationship of Sleep Duration With All-Cause Mortality and Cardiovascular Events: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(9) doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.005947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Strand LB, Tsai MK, Gunnell D, Janszky I, Wen CP, Chang SS. Self-reported sleep duration and coronary heart disease mortality: A large cohort study of 400,000 Taiwanese adults. Int J Cardiol. 2016;207:246–251. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosengren A, Smyth A, Rangarajan S, et al. Socioeconomic status and risk of cardiovascular disease in 20 low-income, middle-income, and high-income countries: the Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiologic (PURE) study. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7(6):e748–e760. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30045-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bell S, Daskalopoulou M, Rapsomaniki E, et al. Association between clinically recorded alcohol consumption and initial presentation of 12 cardiovascular diseases: population based cohort study using linked health records. BMJ. 2017;356:j909. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ricci C, Wood A, Muller D, et al. Alcohol intake in relation to non-fatal and fatal coronary heart disease and stroke: EPIC-CVD case-cohort study. BMJ. 2018;361:k934. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lavie CJ, Milani RV, Ventura HO. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: risk factor, paradox, and impact of weight loss. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53(21):1925–1932. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.12.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lavie CJ, Laddu D, Arena R, Ortega FB, Alpert MA, Kushner RF. Healthy Weight and Obesity Prevention: JACC Health Promotion Series. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(13):1506–1531. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.08.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.