Abstract

Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) are serious adverse cutaneous drug reactions, characterized by epidermal detachment and mucous membrane involvement. SJS/TEN is more common in female patients, with unique findings in the ocular and vulvar regions. Early recognition and intervention, as well as long-term follow-up, are crucial to prevent devastating scarring and sequelae. This review examines the vulvar and ocular manifestations of SJS/TEN and describes the current treatment recommendations for female patients, requiring close consultation and collaboration among dermatology, ophthalmology, and gynecology.

Keywords: Stevens–Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, cutaneous drug eruption, vulvar involvement, ocular-surface, dry eye

What is known about this subject in regard to women and their families?

• Stevens–Johnson's syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermic necrolysis (TEN) are more common in women.

• Long-term sequelae can profoundly affect vaginal and ocular surface health, including vision loss and dry eye syndrome.

What is new from this article as messages for women and their families?

• Early intervention with a multidisciplinary approach, including dermatology, ophthalmology, and gynecology, is crucial to reduce scarring and improve outcomes and the quality of life of female patients with SJS and TEN.

• Long-term follow-up with dermatology, ophthalmology, and gynecology is also necessary in female survivors of SJS/TEN because of ongoing chronic inflammation and the higher risk for ocular surface disease and gynecologic neoplasias.

• Sex-related differences in ocular surface may predispose women to more severe ocular complications in SJS/TEN, and future studies are needed to investigate the inflammatory response of female survivors with SJS/TEN.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

Introduction

Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) are immune-mediated, life-threatening, adverse drug reactions, characterized by epidermal and mucous membrane detachment. The incidence of SJS/TEN ranges from 1.6 to 9.2 cases per million per year in the United States, and the mortality rate can approach 15% to 49%, making early intervention vital (Seminario-Vidal et al., 2020).

Several manuscripts from around the world suggest that SJS/TEN is more common in female than male patients, with an incidence ranging from 52% to 68% (Hsu et al., 2016; Kannenberg et al., 2012; Micheletti et al., 2018; Saka et al., 2013; Sekula et al., 2011; Sunaga et al., 2020). The prevalence of vulvovaginal involvement in women with SJS/TEN is as high as 70%, but may be underestimated because of the focus on critical care in the early phase of the illness or the sensitive nature of examination of the genitourinary area (Kaser et al., 2011; Meneux et al., 1998).

Several retrospective studies on ocular SJS/TEN report that female patients are more commonly affected (Cabañas Weisz et al., 2020; Kohanim et al., 2016b; Power et al., 1995; Saka et al., 2019; Sotozono et al., 2015). The severity of ocular disease in women with SJS/TEN has not been well studied, partly because the results are often presented as one group, but a few reports indicate that women have worse disease. Kim et al. (2015) reported that female sex was the strongest prognostic factor for the severity of chronic ocular-surface complications and worse final vision in survivors with SJS/TEN. Also, in a retrospective study on the ocular sequelae of SJS/TEN, 64% to 67% of patients with severe or very severe ocular disease were female (Sotozono et al., 2015). More recent studies report an association between female sex and worse final vision in patients with chronic ocular complications in SJS/TEN or higher rates of lid-related keratopathy in adult female patients with SJS (Hall et al., 2021; Shanbhag et al., 2020c).

These findings highlight the need for more sex-specific studies in SJS/TEN to investigate whether the known structural differences in the female ocular surface predisposes women to post-SJS/TEN complications, such as dry eye disease, which affects 59% of survivors (Gueudry et al., 2009; Matossian et al., 2019; Nelson et al., 2017). Women have greater expression of the transglutaminase 1 gene, which plays a role in surface keratinization, as well as lower conjunctival goblet cell numbers and more meibombian gland dysfunction, all contributing to the loss of homeostasis of the tear film and dry eye symptoms (Connor et al., 1999; Sullivan et al., 2017; Viso et al., 2012). Other risk factors, such as menopause, hormone replacement therapy, and autoimmune diseases, also play a role (Clayton, 2018; Nelson et al., 2017; Vehof et al., 2020).

The pathogenesis of ocular SJS/TEN disease severity and dry eye in female survivors is likely due to a combination of sex-specific predisposition for ocular-surface inflammation and chronic sequelae, such as keratinization and cicatricial changes (Iyer et al., 2020; Kohanim et al., 2016a; Lekhanont et al., 2019a; Matossian et al., 2019; Singh et al., 2021b; 2021c; Sotozono et al., 2018; Sullivan et al., 2017). Despite the existing knowledge gap concerning the female inflammatory response in SJS/TEN, abatement of the acute phase is known to lead to improved long-term outcomes (Gregory, 2011; Kohanim et al., 2016a; Saeed and Chodosh, 2016; Shanbhag et al., 2020a). This review will focus on the pathophysiologic changes and therapies in vulvovaginal and ocular mucosal surface involvement of SJS/TEN and provide recommendations for the management of SJS/TEN.

Vulvovaginal involvement in SJS/TEN

Women with vulvovaginal SJS/TEN experience significant pain and morbidity and have the potential for long-term complications, especially when not recognized and treated early in the course of disease. This section reviews the gynecologic surface anatomy and the pathophysiology and guidelines for treatment of the vulvovaginal involvement in SJS/TEN.

Gynecologic anatomy

Several anatomic structures make up the external part of the female genitalia, collectively called the vulva. The vulva protects a woman's sexual organs, urethral orifice, and vagina. The skin of the mons pubis, labia, clitoris, and perineum is derived from the embryonic ectoderm and has a keratinized, stratified, squamous structure with sweat glands, sebaceous glands, and hair follicles (Jones, 1983).

Vagina

The vagina is of mesodermal origin and has nonkeratinized squamous epithelium that is responsive to ovarian steroid hormone cycling, which changes with menopause (Nauth, 1993). Lactic acid–producing Lactobacillus species predominate in the vaginal flora of healthy women protecting against pathogenic organisms and inflammatory conditions (Marshall and Tanner, 1981; Van De Wijgert et al., 2014). Therefore, vaginal biome dysbiosis is associated with an increased risk of infection and inflammation (van de Wijgert and Jespers, 2017).

Urethra

The urethra is a tubular structure approximately 3 cm in length and is the distal portion of the urinary tract. The urethra is situated in the vulva, anterior to the vaginal introitus. An epithelial, lamina propria, and muscular layer surrounds the urethral lumen, with adipose and loose fibroconnective tissue separating the urethra from the anterior vagina (Mahoney et al., 2017; Mazloomdoost et al., 2017).

Acute gynecologic involvement in SJS/TEN and management

Acute vulvar SJS/TEN lesions can affect both the keratinized and nonkeratinized epithelia and are typically erosions and ulcerations, with bullae rarely seen. Patients may experience pain, swelling, and dysuria. When the vagina is involved, there is erosive and extensive vaginitis with purulent blood-stained vaginal discharge, although at times there may be no discharge or symptoms and a high index of suspicion is necessary. Without treatment, the time to resolution of the vulvovaginal lesions ranges from 7 to 56 days (Meneux et al., 1998).

Vulvar examination

The importance of a daily total body skin examination, inclusive of the vulvar mucosa, perineum, perianal skin, and anus, cannot be overstated. This examination is noninvasively accomplished by having the patient draw her heels up toward her buttocks and allow the knees to drop to the sides, or the patient may lie on her side, top knee slightly bent and in front of the bottom leg, with the buttocks spread by the examiner. Such examination should be completed daily until discharge because delayed mucosal inflammation is possible, as are side effects from medical management, such as vaginal candidiasis.

Although a speculum examination would reveal the extent and location of vaginal ulceration and desquamation, such an examination is painful and often distressing for the patient. Experts have suggested assuming there is vaginal involvement in such cases, especially when the vaginal introitus is involved (O'Brien et al., 2019).

Management of acute SJS/TEN

To date, there have been no prospective clinical trials to study the treatment and supportive care of women with vulvovaginal SJS/TEN; recommendations rely on expert opinion from dermatologists and gynecologists (Emberger et al., 2006; Meneux et al., 1998; O'Brien et al., 2019). The goals of therapy should be to protect vaginal function by decreasing adhesion formation and agglutination, as well as limiting metaplastic and potentially neoplastic changes in affected tissue. Mainstays of care include the insertion of a Foley catheter, topical application of corticosteroids, menstrual suppression, and vaginal dilator physical therapy, as described in detail in Table 1 and Figure 1 (Kaser et al., 2011; O'Brien et al., 2019).

Table 1.

Medical management of and gynecologic procedures in acute vulvovaginal SJS/TEN

| Medical management of acute vulvovaginal SJS/TEN | |

|---|---|

| General care |

|

| Urethral erosions and/or dysuria |

|

| Vulvar erosions (Fig. 1) |

|

| Vulvar pain |

|

| Intravaginal erosions Speculum examination may be too painful for patient; thus, vaginal involvement can often be assumed when vulvar erosions are present |

|

| Menstrual suppression |

|

| Gynecologic procedures in acute vulvovaginal SJS/TEN | |

|---|---|

| Vaginal dilation therapy |

|

SJS, Stevens–Johnson syndrome; TES, toxic epidermal necrolysis.

Fig. 1.

Photograph of dilation therapy during re-epithelialization, 12 days after admission for toxic epidermal necrolysis. In this case, a vaginal ultrasound endocavity probe cover containing rolled 4 × 4 gauze pads was used to create a soft, flexible dilator for this virginal woman with a history of tampon use.

Subacute vulvovaginal SJS/TEN

Follow-up with gynecology is necessary after hospital discharge to manage subacute vulvovaginal SJS/TEN inflammation and monitor for any evolving side effects from medications. Rates of follow up with gynecology after discharge have not been well studied, but likely are reflective of the low rates of gynecologic consultation in the hospital phase.

Chronic vulvovaginal sequelae of SJS/TEN

Although chronic urogenital compilations are less common than at other mucosal sites, several chronic manifestations are well described, including anatomic alterations, physiologic changes, dysthesia, and psychosocial impairments (Emberger et al., 2006; Wilson and Malinak, 1988).

Scar tissue and stenosis

Mucosal erosions promote adhesions of the vagina or labia, and the resultant scar formation may lead to vaginal synechiae, loss of vulvar tissue architecture (agglutination), fusion of the anatomic structures of the vulva, and stenosis or occlusion of the vagina and urethra (De Jesus et al., 2012; Hart et al., 2002). Possible sequelae from obstructed urinary stream and menstrual egress include urinary retention, recurrent cystitis, postvoid dribbling, hematocolpos, hematometra, and endometriosis (Meneux et al., 1998; Van Batavia et al., 2017).

Metaplasia

Metaplastic cervical or endometrial epithelium in the vaginal wall has been described in multiple case reports after SJS/TEN in adults. This is thought to result from p63 suppression in the basal cells of the vaginal and cervical epithelium in SJS/TEN, which allows for vaginal squamous epithelium to be replaced by glandular epithelium (Noël et al., 2005). Vulvovaginal adenosis has the potential to transform into squamous cell, mucinous, and clear cell carcinoma of the vagina (Ghosh and Cera, 1983; Kranl et al., 1998; Scurry et al., 1991). The risk of vulvovaginal metaplasia and neoplasia in SJS/TEN survivors has not been studied to date (Emberger et al., 2006). SJS/TEN survivors with persistent gynecologic symptoms or lesions should undergo punch biopsy of the vulva and vagina and have close observation with colposcopy if the biopsy is positive for adenosis (Kaser et al., 2011).

Genital symptoms in survivors of SJS/TEN

Sexual dysfunction secondary to SJS/TEN is likely more common than reported in the literature. There are no published studies reporting sexual function in survivors of SJS/TEN, although several case reports and patient focus groups mention dyspareunia, chronic pruritus and pain, and vulvodynia as sequelae (Meneux et al., 1998; Petukhova et al., 2016). Other genital sequelae include functional dryness, tissue fragility, and bleeding (Chang et al., 2020). Early return to sexual intercourse after re-epithelialization (or dilator therapy in patients not sexually active) and referrals to pelvic floor physical therapy can help with vulvodynia, dyspareunia, vaginismus, or involuntary contracture of musculature, as well as improve pelvic floor muscle tone (Kaser et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2016; O'Brien et al., 2019).

Ocular considerations in SJS/TEN

The ocular surface is affected in 46% of 88% of all patients with SJS/TEN. Late ocular complications of SJS/TEN are associated with the severity of ocular disease in the acute phase (Power et al., 1995; Sotozono et al., 2007; 2015; Yoshikawa et al., 2020b). Progression of SJS/TEN ocular-surface inflammation can lead to severe dryness, ulceration, scar tissue formation, and keratinization of the ocular surface, affecting long-term visual outcomes and quality of life in these patients (Gueudry et al., 2009; Power et al., 1995; Tougeron-Brousseau et al., 2009). Therefore, early recognition of ocular involvement and implementation of targeted treatment are essential to downregulate inflammation and prevent sequelae (Gregory, 2011; Kohanim et al., 2016a; Saeed and Chodosh, 2016; Saeed et al., 2020). This is particularly important for female patients because they have a higher risk for dry eye disease and may be more susceptible for chronic ocular-surface disease in SJS/TEN (Matossian et al., 2019; Smith et al., 2007; Sullivan et al., 2017).

Ocular-surface anatomy

Table 2 describes the ocular-surface components in health along with pathophysiologic changes observed in patients with SJS/TEN. The ocular surface consists of the eyelids, meibomian glands (MG), conjunctiva, cornea, main and accessory lacrimal glands (LG), and tear film (TF). All elements of the ocular surface are interconnected and contribute to its health, maintenance, and repair (Biber, 2013; Craig et al., 2017). The eyelids provide protection; house the MGs, which release tear-stabilizing lipid into the TF; and spread the TF over the surface to avoid premature evaporation. With every blink, the TF lubricates the surface and distributes nutrients (Willcox et al., 2017). The human TF proteome also contains 1800 different proteins, including immunoglobulins, cytokines, growth factors (GF), neuropeptides, lysozyme, and matrix-metallopeptidases to protect and maintain the ocular surface (Willcox et al., 2017). The corneal epithelium is continuously supplied by limbal stem cells (LSCs) residing at the corneal margin and depends on GF for repair (Holland et al., 2013). Finally, the conjunctiva, a mucosal surface, is a protective barrier that covers the entire ocular surface (except for the cornea) and is severely affected in SJS/TEN (Harvey et al., 2013).

Table 2.

Ocular-surface components in health and SJS/TEN

| Components of ocular surface | Function | SJS/TEN-related damage | Previous studies |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Eyelids Meibomian gland orifices at lid margin |

|

|

|

|

Conjunctiva Goblet cells (embedded in conjunctiva) Accessory lacrimal glands Lymphoid tissue layer in lamina propria: Resident immune cells: T cells (CD3+), macrophages (CD68+), natural killer cells, IgA-producing plasma cells and mast cells Conjunctiva-associated lymphoid tissue is part of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue, and lymphoid follicles are predominantly in tarsal conjunctiva (Hingorani et al., 1997; Knop and Knop, 2000) Innate Immune system |

|

|

|

|

Cornea Epithelium Corneal nerve plexus Limbal stem cells (at the corneal margins) |

|

|

|

|

Tear film Lipid layer Aqueous layer Mucin layer Lacrimal glands Main Accessory lacrimal glands |

|

|

|

IL, interleukin; SJS, Stevens–Johnson syndrome; TES, toxic epidermal necrolysis

Ocular-surface changes in SJS/TEN

Ocular-surface homeostasis is disrupted in ocular SJS/TEN, and inflammation ranges from mild conjunctivitis to suppurative membranous conjunctivitis, often followed by fibrosis (Kohanim et al., 2016a). Ocular disease severity is considered the primary risk factor for long-term complications in SJS/TEN, and the goal of ocular therapy is to treat inflammation aggressively and as early as possible to prevent scarring and chronic inflammatory changes (Gregory, 2011; Kohanim et al., 2016a; Thorel et al., 2020).

Acute ocular involvement and management in SJS/TEN

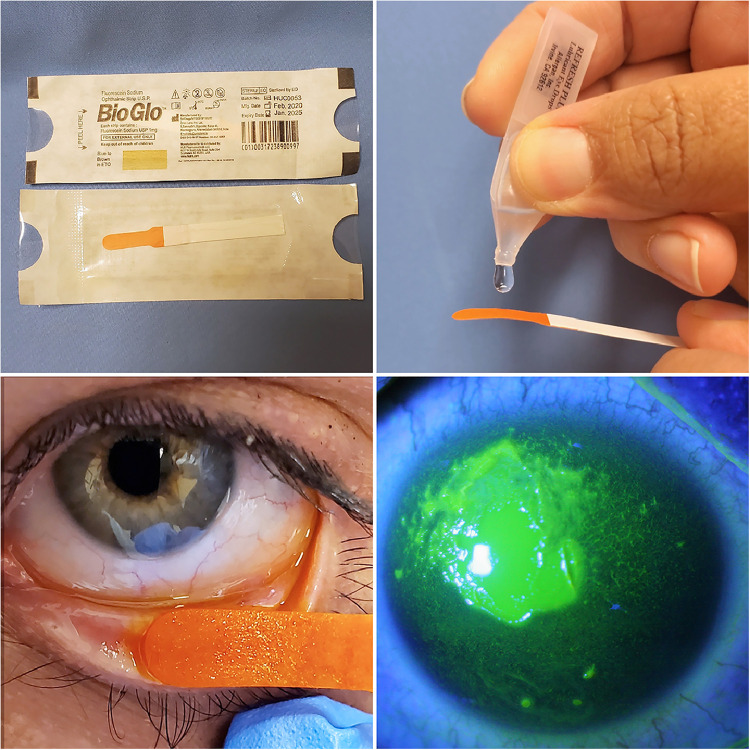

The first sign of acute ocular involvement within 1 to 5 days is conjunctival hyperemia. Once conjunctivitis occurs, medical management should be initiated, and the ocular surface should be examined daily for epithelial defects, which can be visualized with nontoxic fluorescein stain for grading and can be performed at bedside (Table 3; Fig. 2). Persistence of epithelial defects poses a risk for infection and scarring (Gregory, 2016). Treatment is advanced based on disease severity, as outlined in Table 3 (Gregory, 2016; Power et al., 1995; Thorel et al., 2020).

Table 3.

Grading and treatment guidelines in acute ocular Stevens–Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis (adapted from Gregory, 2016)

| Before grading, flush ocular surface with balanced salt solution or 0.9% saline solution to clear mucus. Always evert upper and lower lid to examine the palpebral conjunctiva for inflammation. For fluorescein staining, touch inside of lower lid briefly with fluorescein strip and have patient blink or open and close lids manually (Fig. 2). | |

|---|---|

| Grade | Treatment |

| Mild | |

| Conjunctival hyperemia only No fluorescein staining |

Preservative-free artificial tears Close daily observation |

| Moderate | |

| Lid margin fluorescein stain <1/3 of length Conjunctival hyperemia Conjunctival fluorescein stain <1 cm Corneal punctate staining, but no defects |

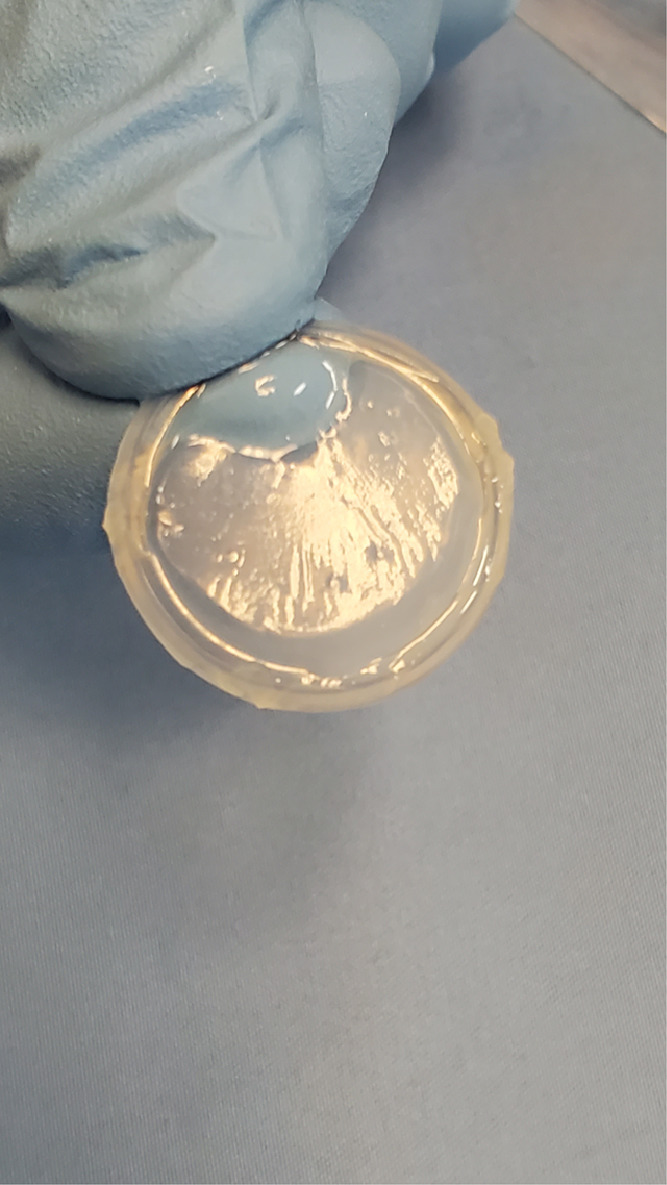

Preservative-free artificial tears every hour Broad-spectrum antibiotic drop (e.g., moxifloxacin) 4 × /day Topical prednisolone acetate 1% drops 4 × /day Consider bedside amnionic membrane disc insertion to reduce inflammation (Fig. 3) |

| Severe | |

| Lid margin fluorescein stain >1/3 of length Conjunctival yellow membranes or peelable pseudo membranes Conjunctival fluorescein stain >1 cm Corneal epithelial defect any size |

Same as above + amnionic membrane transplant to cover complete ocular surface, including lid margins |

| Very severe | |

| Same as severe + >1/3 of lid margin and >1 eye lid affected Conjunctival fluorescein stain multiple areas Corneal epithelial defects any size |

Same as above + may need repeat amnionic membrane transplant within 1-2 weeks |

Fig. 2.

Fluorescein staining of the ocular surface. A sterile fluorescein strip is moistened with artificial tears or saline solution and then used to touch the lower lid conjunctiva to release fluorescein. After a few blinks, the ocular surface is evaluated for epithelial defects on the conjunctiva and cornea (bottom right) using a blue light filter. The fluorescein stain is not toxic to the surface.

Medical management

Medical treatment of acute ocular involvement in SJS /TEN is directed toward aggressively reducing inflammation with systemic immunosuppression and/or topical steroid therapy depending on the severity of the disease. Sotozono et al. (2009) reported that early topical steroid use resulted in significantly better visual outcomes in a study of 94 patients with SJS. Additionally, aggressive hourly topical lubrication with preservative-free artificial tears is necessary to dilute the concentrations of proinflammatory agents and support epithelial healing (Jain et al., 2016).

Once membranous conjunctivitis occurs or the corneal and/or conjunctival surface develop epithelial defects, then additional, more aggressive intervention with amnionic membrane tissue (AMT), which contains anti-inflammatory components and growth factors, is necessary to control inflammation.

Ocular procedures in acute SJS/TEN

A commercially available cryopreserved human AMT suspended over a ring (Prokera-Slim Corneal Bandage, Biotissue Inc., Miami, FL) can be inserted at bedside or the clinic to protect the cornea or help heal epithelial defects (Fig. 3). The ring is replaced if the AMT dissolves and inflammation persists. Although easy to use, the AMT ring does not cover the entire ocular surface and may not prevent symblepharon (adhesion of conjunctival surfaces) formation in noncovered areas (Shay et al., 2010).

Fig. 3.

Commercially available amnionic membrane disc suspended over a ring (Prokera Slim, Biotissue, Miami, FL) can be inserted into (and removed from) the inflamed eye at bedside or the clinic.

In severe cases, early application of AMT with cryopreserved tissue (Amniograft, Biotissue Inc.) is recommended to completely cover the ocular surface from above the lid margins inside the lids and over the cornea. This procedure can be performed at bedside or in the operating room and can be repeated every 14 days until the inflammation resolves (Gregory, 2011; Ma et al., 2016; Saeed et al., 2020; Shay et al., 2009). Several case series have shown that early intervention with AMT (preferably within 5 days of onset of symptoms) can abate symblepharon formation and fornix foreshortening, promote epithelial healing, and result in good visual outcomes (Araki et al., 2009; Gregory, 2016; Hsu et al., 2012; Kohanim et al., 2016a; Shammas et al., 2010; Shanbhag et al., 2020b; Shay et al., 2010). Therefore, early consultation with ophthalmology is strongly recommended.

Subacute ocular SJS/TEN

The subacute stage of the disease is characterized by chronic inflammation, severe dryness, and eyelid inflammation (Gurumurthy et al., 2018; Jain et al., 2016). Aggressive lubrication, fitting with a fluid-filled scleral contact lens to protect the cornea, and meticulous eyelid hygiene are important to avoid mechanical shearing and further damage to the ocular surface (Di Pascuale et al., 2005; Tougeron-Brousseau et al., 2009). Importantly, Yoshikawa et al. (2020a) reported progression of chronic disease in 33.3% of the eyes of patients with SJS/TEN followed over 5 years. This finding underscores the importance of early referral to an ophthalmologist for long-term management of inflammation, dry eye disease, and vision preservation in patients with SJS/TEN.

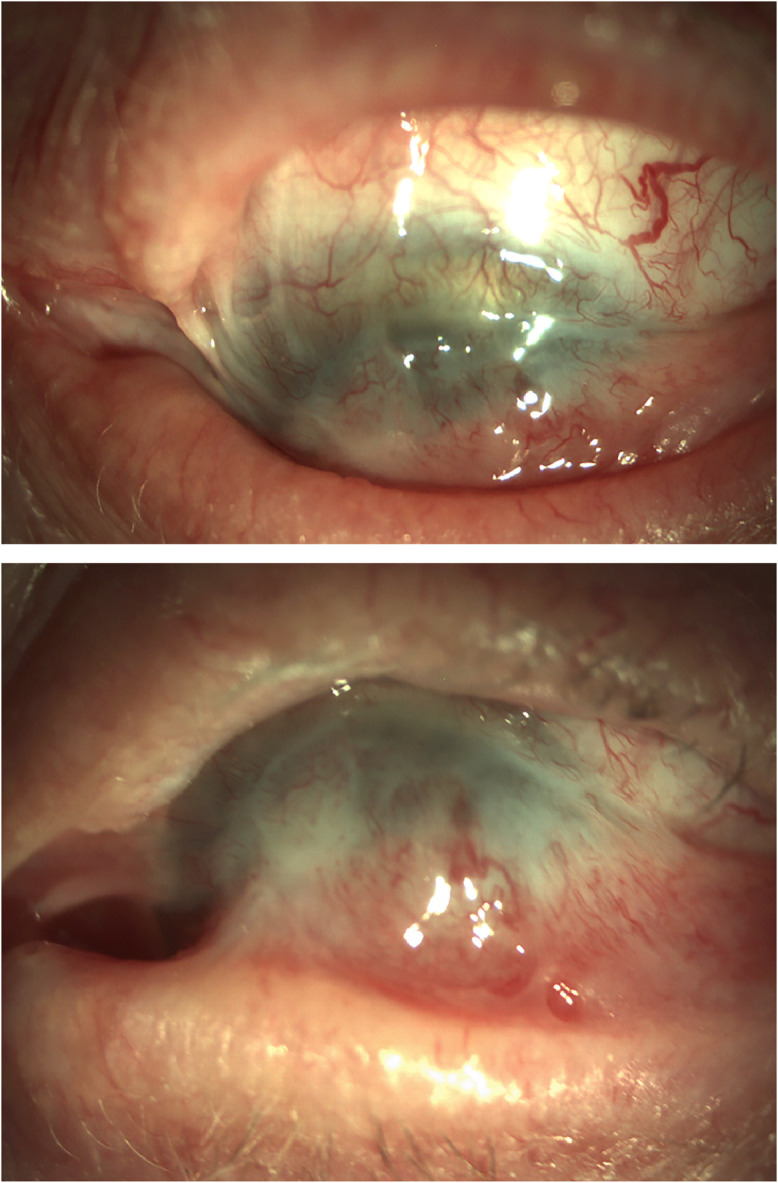

Chronic ocular sequelae of SJS/TEN

Chronic profibrotic inflammation starts approximately 8 weeks after initial onset and is observed in 35% to 50% of patients with SJS/TEN. Chronic cicatricial changes include symblepharon formation, trichiasis, eyelid margin rotation, and keratinization in up to 70% of patients, loss of MG in up to 79% of patients, scarring of LG ductules, loss of accessory LG, loss of mucin-producing goblet cells, loss of GF, abnormal corneal nerves, and LSC deficiency with inability to regenerate the corneal epithelium, resulting in loss of vision (Di Pascuale et al., 2005; Gurumurthy et al., 2018; Iyer et al., 2020; Kohanim et al., 2016b; Lekhanont et al., 2019; Nelson and Wright, 1984; Singh et al., 2021a; Sotozono et al., 2018; Ueta, 2018; Ueta and Kinoshita, 2010; Vera et al., 2009; Williams et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2016; Yoshikawa et al., 2020a; Fig. 4). Visual rehabilitation in these patients encompasses multiple surgeries, including removal of keratinization and salivary gland, mucous membrane, LSC, and corneal transplantations (Kohanim et al., 2016a; Lopez-Garcia et al., 2011).

Fig. 4.

(A) Symblepharon formation in a patient with chronic Stevens–Johnson syndrome showing conjunctivalization of the cornea, scarring, and loss of inferior conjunctival fornix. (B) Loss of motility on upward gaze (photograph courtesy of Dr. Joseph Pasternak).

End-stage SJS/TEN results in corneal blindness and a long process of ocular-surface reconstruction with implantation of a keratoprosthesis. However, the prognosis for good vision and prosthesis retention after surgery in patients with SJS/TEN is lower compared with other severe ocular-surface diseases (Sayegh et al., 2008).

Conclusion

The vulvovaginal and ocular mucosal surfaces are affected in the majority of female patients with SJS/TEN. Prevention of mucosal scarring is essential for the quality of life of survivors. Early and daily examination, grading, aggressive treatment of the vulva and ocular surface, as well as long-term follow-up of female patients with SJS/TEN with a dermatologist, ophthalmologist, and gynecologist are necessary to treat ongoing chronic progressive mucosal surface inflammation, minimize devastating long-term sequelae, and monitor for gynecologic neoplasia.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Funding

This work was supported by the Division of Intramural Research of the National Eye Institute.

Study approval

The author(s) confirm that any aspect of the work covered in this manuscript that has involved human patients has been conducted with the ethical approval of all relevant bodies.

Disclosures

[HP] The opinions and assertions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Uniformed Services University or the Department of Defense. Neither I nor my family members have a financial interest in any commercial product, service, or organization providing financial support for this research. This work was prepared by a military or civilian employee of the US Government as part of the individual’s official duties and therefore is in the public domain and does not possess copyright protection (public domain information may be freely distributed and copied; however, as a courtesy it is requested that the Uniformed Services University and the author be given an appropriate acknowledgement).

References

- Araki Y, Sotozono C, Inatomi T, Ueta M, Yokoi N, Ueda E, et al. Successful treatment of Stevens–Johnson syndrome with steroid pulse therapy at disease onset. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;147:1004–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.12.040. e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Batavia JP, Chu DI, Long CJ, Jen M, Canning DA, Weiss DA. Genitourinary involvement and management in children with Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Pediatr Urol. 2017;13 doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2017.01.018. 490.e1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biber JM. Classification of ocular surface disease, 2nd ed. In: Holland EJ, Mannis MJ, Lee BW, editors. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier; 2013. pp. 35–44.

- Cabañas Weisz LM, Miguel Escuredo I, Ayestarán Soto JB, García Gutiérrez JJ. Toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN): Acute complications and long-term sequelae management in a multidisciplinary follow-up. J Plast Reconstr Aesthetic Surg. 2020;73:319–327. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2019.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang WC, Abe R, Anderson P, Anderson W, Ardern-Jones MR, Beachkofsky TM, et al. SJS/TEN 2019: From science to translation. J Dermatol Sci. 2020;98:2–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2020.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton JA. Dry eye. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(23):2212–2223. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1407936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor C, Flockencier L, Hall C. The influence of gender on the ocular surface. J Am Optom Assoc. 1999;70:182–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig JP, Nelson JD, Azar DT, Belmonte C, Bron AJ, Chauhan SK, et al. TFOS DEWS II report executive summary. Ocul Surf. 2017;15:802–812. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2017.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jesus LE, Dekermacher S, Manhães CR, Faria LM, Barros ML. Acquired labial sinechiae and hydrocolpos secondary to Stevens–Johnson syndrome. Urology. 2012;80:919–921. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2012.06.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Pascuale MA, Espana EM, Liu DTS, Kawakita T, Li W, Gao YY, et al. Correlation of corneal complications with eyelid cicatricial pathologies in patients with Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis syndrome. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:904–912. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emberger M, Lanschuetzer CM, Laimer M, Hawranek T, Staudach A, Hintner H. Vaginal adenosis induced by Stevens–Johnson syndrome. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:896–898. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.01586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh TK, Cera PJ. Transition of benign vaginal adenosis to clear cell carcinoma. Obstet Gynecol. 1983;61:126–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory DG. New grading system and treatment guidelines for the acute ocular manifestations of Stevens–Johnson syndrome. Ophthalmology. 2016;123:1653–1658. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.04.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory DG. Treatment of acute Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis using amniotic membrane: A review of 10 consecutive cases. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:908–914. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gueudry J, Roujeau JC, Binaghi M, Soubrane G, Muraine M. Risk factors for the development of ocular complications of Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:157–162. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2009.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurumurthy S, Iyer G, Srinivasan B, Agarwal S, Angayarkanni N. Ocular surface cytokine profile in chronic Stevens–Johnson syndrome and its response to mucous membrane grafting for lid margin keratinisation. Br J Ophthalmol. 2018;102:169–176. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2017-310373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall LN, Shanbhag SS, Rashad R, Chodosh J, Saeed HN. The effects of systemic cyclosporine in acute Stevens–Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis on ocular disease. Ocul Surf. 2021;19:128–132. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2020.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart R, Minto C, Creighton S. Vaginal adhesions caused by Stevens–Johnson syndrome. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2002;15:151–152. doi: 10.1016/s1083-3188(02)00146-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey TM, Fernandez AGA, Patel R, Goldman D, Ciralsky J. Elsevier; Amsterdam, Netherlands: 2013. Conjunctival anatomy and physiology. [Google Scholar]

- Holland EJ, Mannis MJ, Lee WB. Ocular surface disease: Cornea, conjunctiva and tear film. Cornea. 2013:1–452. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu DY, Brieva J, Silverberg NB, Silverberg JI. Morbidity and mortality of Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in United States adults. J Invest Dermatol. 2016;136:1387–1397. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2016.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu M, Jayaram A, Verner R, Lin A, Bouchard C. Indications and outcomes of amniotic membrane transplantation in the management of acute Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: A case-control study. Cornea. 2012;31:1394–1402. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31823d02a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer G, Srinivasan B, Agarwal S. Ocular sequelae of Stevens–Johnson syndrome. Cornea. 2020;39:S3–S6. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000002532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain R, Sharma N, Basu S, Iyer G, Ueta M, Sotozono C, et al. Stevens–Johnson syndrome: The role of an ophthalmologist. Surv Ophthalmol. 2016;61:369–399. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2016.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones IS. A histological assessment of normal vulval skin. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1983;8:513–521. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1983.tb01818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannenberg SMH, Jordaan HF, Koegelenberg CFN, Von Groote-Bidlingmaier F, Visser WI. Toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens–Johnson syndrome in South Africa: A 3-year prospective study. QJM. 2012;105:839–846. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcs078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaser DJ, Reichman DE, Laufer MR. Prevention of vulvovaginal sequelae in Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2011;4:81–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DH, Yoon KC, Seo KY, Lee HS, Yoon SC, Sotozono C, et al. The role of systemic immunomodulatory treatment and prognostic factors on chronic ocular complications in Stevens–Johnson syndrome. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:254–264. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohanim S, Palioura S, Saeed HN, Akpek EK, Amescua G, Basu S, et al. Stevens–Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis-A comprehensive review and guide to therapy I. Ocul Surf. 2016;14:2–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2015.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohanim S, Palioura S, Saeed HN, Akpek EK, Amescua G, Basu S, et al. Acute and chronic ophthalmic involvement in Stevens–Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis-A comprehensive review and guide to therapy II. Ocul Surf. 2016;14:168–188. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2016.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranl C, Zelger B, Kofler H, Heim K, Sepp N, Fritsch P. Vulval and vaginal adenosis. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:128–131. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HY, Walsh SA, Creamer D, Lebargy F, Wolkenstein P, Gisselbrecht M, et al. Vulval adenosis associated with toxic epidermal necrolysis (multiple letters) Br J Dermatol. 2016;153:1387–1397. [Google Scholar]

- Lekhanont K, Jongkhajornpong P, Sontichai V, Anothaisintawee T, Nijvipakul S. Evaluating dry eye and meibomian gland dysfunction with meibography in patients with Stevens–Johnson syndrome. Cornea. 2019;38:1489–1494. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000002025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Garcia JS, Rivas Jara L, Garca-Lozano CI, Conesa E, De Juan IE, Murube Del Castillo J. Ocular features and histopathologic changes during follow-up of toxic epidermal necrolysis. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:265–271. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma KN, Thanos A, Chodosh J, Shah AS, Mantagos IS. A novel technique for amniotic membrane transplantation in patients with acute Stevens–Johnson syndrome. Ocul Surf. 2016;14:31–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2015.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney C, Smith A, Marshall A, Reid F. Pelvic floor dysfunction and sensory impairment: Current evidence. Neurourol Urodyn. 2017;36:550–556. doi: 10.1002/nau.23004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall W, Tanner J. Puberty, 2nd ed. In: Davis J, editor. Science Foundation Pediatrics. London, United Kingdom: Heinemann; 1981.

- Matossian C, McDonald M, Donaldson KE, Nichols KK, Maciver S, Gupta PK. Dry eye disease: Consideration for women's health. J Womens Health. 2019;28:502–514. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2018.7041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazloomdoost D, Westermann LB, Mutema G, Crisp CC, Kleeman SD, Pauls RN. Histologic anatomy of the anterior vagina and urethra. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2017;23:329–335. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0000000000000387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meneux E, Wolkenstein P, Haddad B, Roujeau JC, Revuz J, Paniel BJ. Vulvovaginal involvement in toxic epidermal necrolysis: A retrospective study of 40 cases. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:283–287. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(97)00596-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micheletti RG, Chiesa-Fuxench Z, Noe MH, Stephen S, Aleshin M, Agarwal A, et al. Stevens–Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis: A multicenter retrospective study of 377 adult patients from the United States. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138:2315–2321. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2018.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nauth H. Dekker; New York, NY: 1993. Vulvovaginitis. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson JD, Craig JP, Akpek EK, Azar DT, Belmonte C, Bron AJ, et al. The tear film and ocular surface society (TFOS) dry eye workshop (DEWS) II: Introduction. Ocul Surf. 2017;15:269–275. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2017.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson JD, Wright JC. Conjunctival goblet cell densities in ocular surface disease. Arch Ophthalmol. 1984;102:1049–1051. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1984.01040030851031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noël JC, Buxant F, Fayt I, Debusschere G, Parent D, McKenna DB, et al. Vulval adenosis associated with toxic epidermal necrolysis (multiple letters) Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:457–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien KF, Bradley SE, Mitchell CM, Cardis MA, Mauskar MM, Pasieka HB. Vulvovaginal manifestations in Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: Prevention and treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019:191–192. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petukhova TA, Maverakis E, Ho B, Sharon VR. Urogynecologic complications in Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: Presentation of a case and recommendations for management. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:202–205. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2016.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power WJ, Ghoraishi M, Merayo-Lloves J, Neves RA, Foster CS. Analysis of the acute ophthalmic manifestations of the erythema multiforme/Stevens–Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis disease spectrum. Ophthalmology. 1995;102:1669–1676. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(95)30811-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeed HN, Bouchard C, Shieh C, Phillips E, Chodosh J. Highlights from the 2nd biennial Stevens–Johnson syndrome symposium 2019: SJS/TEN from science to translation. Ocul Surf. 2020;18:483–486. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2019.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeed HN, Chodosh J. Immunologic mediators in Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Semin Ophthalmol. 2016;31:85–90. doi: 10.3109/08820538.2015.1115255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saka B, Akakpo AS, Teclessou JN, Mahamadou G, Mouhari-Toure A, Dzidzinyo K, et al. Ocular and mucocutaneous sequelae among survivors of Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in Togo. Dermatol Res Pract. 2019;2019 doi: 10.1155/2019/4917024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saka B, Barro-Traoré F, Atadokpédé FA, Kobangue L, Niamba PA, Adégbidi H, et al. Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in sub-Saharan Africa: A multicentric study in four countries. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:575–579. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2012.05743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayegh RR, Ang LPK, Foster CS, Dohlman CH. The Boston keratoprosthesis in Stevens–Johnson Syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;145:438–444. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scurry J, Planner R, Grant P. Unusual variants of vaginal adenosis: A challenge for diagnosis and treatment. Gynecol Oncol. 1991;41:172–177. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(91)90280-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekula P, Liss Y, Davidovici B, Dunant A, Roujeau JC, Kardaun S, et al. Evaluation of SCORTEN on a cohort of patients with Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis included in the RegiSCAR study. J Burn Care Res. 2011;32:237–245. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e31820aafbc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seminario-Vidal L, Kroshinsky D, Malachowski SJ, Sun J, Markova A, Beachkofsky TM, et al. Society of Dermatology Hospitalists supportive care guidelines for the management of Stevens–Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis in adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1553–1567. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.02.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shammas MC, Lai EC, Sarkar JS, Yang J, Starr CE, Sippel KC. Management of acute Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis utilizing amniotic membrane and topical corticosteroids. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;149:203–213. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2009.08.040. e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanbhag SS, Chodosh J, Fathy C, Goverman J, Mitchell C, Saeed HN. Multidisciplinary care in Stevens–Johnson syndrome. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2020;11:1–17. doi: 10.1177/2040622319894469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanbhag SS, Hall L, Chodosh J, Saeed HN. Long-term outcomes of amniotic membrane treatment in acute Stevens–Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis. Ocul Surf. 2020;18:517–522. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2020.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanbhag SS, Shah S, Singh M, Bahuguna C, Donthineni PR, Basu S. Lid-related keratopathy in Stevens–Johnson syndrome: Natural course and impact of therapeutic interventions in children and adults. Am J Ophthalmol. 2020;219:357–365. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2020.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shay E, Khadem JJ, Tseng SCG. Efficacy and limitation of sutureless amniotic membrane transplantation for acute toxic epidermal necrolysis. Cornea. 2010;29:359–361. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181acf816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shay E, Kheirkhah A, Liang L, Sheha H, Gregory DG, Tseng SCG. Amniotic membrane transplantation as a new therapy for the acute ocular manifestations of Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Surv Ophthalmol. 2009;54:686–696. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S, Ali MJ, Mittal V, Brabletz S, Paulsen F. Immunohistological study of palpebral lobe of the lacrimal gland in severe dry eyes secondary to Stevens–Johnson syndrome. Curr Eye Res. 2021;46:789–795. doi: 10.1080/02713683.2020.1836227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S, Jakati S, Shanbhag SS, Elhusseiny AM, Djalilian AR, Basu S. Lid margin keratinization in Stevens–Johnson syndrome: Review of pathophysiology and histopathology. Ocul Surf. 2021;21:299–305. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2021.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S, Mishra DK, Shanbhag S, Vemuganti G, Singh V, Ali MJ, et al. Lacrimal gland involvement in severe dry eyes after Stevens–Johnson syndrome. Ophthalmology. 2021;128:621–624. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JA, Albenz J, Begley C, Caffery B, Nichols K, Schaumberg D, et al. The epidemiology of dry eye disease: Report of the epidemiology subcommittee of the international Dry Eye WorkShop (2007) Ocul Surf. 2007;5:93–107. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70082-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotozono C, Ang LPK, Koizumi N, Higashihara H, Ueta M, Inatomi T, et al. New grading system for the evaluation of chronic ocular manifestations in patients with Stevens–Johnson syndrome. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:1294–1302. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotozono C, Ueta M, Koizumi N, Inatomi T, Shirakata Y, Ikezawa Z, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis with ocular complications. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:685–690. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.12.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotozono C, Ueta M, Nakatani E, Kitami A, Watanabe H, Sueki H, et al. Predictive factors associated with acute ocular involvement in Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;160:228–237. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2015.05.002. e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotozono C, Ueta M, Yokoi N. Severe dry eye with combined mechanisms is involved in the ocular sequelae of SJS/TEN at the chronic stage. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018;59 doi: 10.1167/iovs.18-24019. DES80–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan DA, Rocha EM, Aragona P, Clayton JA, Ding J, Golebiowski B, et al. TFOS DEWS II sex, gender, and hormones report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15:284–333. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2017.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunaga Y, Kurosawa M, Ochiai H, Watanabe H, Sueki H, Azukizawa H, et al. The nationwide epidemiological survey of Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in Japan, 2016–2018. J Dermatol Sci. 2020;100:175–182. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2020.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorel D, Ingen-Housz-Oro S, Royer G, Delcampe A, Bellon N, Bodemer C, et al. Management of ocular involvement in the acute phase of Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: French national audit of practices, literature review, and consensus agreement. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2020;15:259. doi: 10.1186/s13023-020-01538-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tougeron-Brousseau B, Delcampe A, Gueudry J, Vera L, Doan S, Hoang-Xuan T, et al. Vision-related function after scleral lens fitting in ocular complications of Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;148:852–859. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2009.07.006. e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueta M. Results of detailed investigations into Stevens–Johnson syndrome with severe ocular complications. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018;59 doi: 10.1167/iovs.17-23537. DES183–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueta M, Kinoshita S. Ocular surface inflammation mediated by innate immunity. Eye Contact Lens. 2010;36:269–281. doi: 10.1097/ICL.0b013e3181ee8971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vehof J, Snieder H, Jansonius N, Hammond CJ. Prevalence and risk factors of dry eye in 79,866 participants of the population-based Lifelines cohort study in the Netherlands: Prevalence and risk factors of dry eye. Ocul Surf. 2020;19:83–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2020.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vera LS, Gueudry J, Delcampe A, Roujeau JC, Brasseur G, Muraine M. In vivo confocal microscopic evaluation of corneal changes in chronic Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Cornea. 2009;28:401–407. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31818cd299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viso E, Rodríguez-Ares M, Abelenda D, Oubiña B, Gude F. Prevalence of asymptomatic and symptomatic meibomian gland dysfunction in the general population of Spain. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:2601–2606. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-9228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van De Wijgert JHHM, Borgdorff H, Verhelst R, Crucitti T, Francis S, Verstraelen H, et al. The vaginal microbiota: What have we learned after a decade of molecular characterization? PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Wijgert JHHM, Jespers V. The global health impact of vaginal dysbiosis. Res Microbiol. 2017;168:859–864. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2017.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willcox MDP, Argüeso P, Georgiev GA, Holopainen JM, Laurie GW, Millar TJ, et al. TFOS DEWS II tear film report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15:366–403. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2017.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams GP, Tomlins PJ, Denniston AK, Southworth HS, Sreekantham S, Curnow SJ, et al. Elevation of conjunctival epithelial CD45INTCD11b+CD16+CD14- neutrophils in ocular Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54:4578–4585. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-11859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson EE, Malinak LR. Vulvovaginal sequelae of Stevens–Johnson syndrome and their management. Obstet Gynecol. 1988;71:478–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang CW, Cho YT, Chen KL, Chen YC, Song HL, Chu CY. Long-term sequelae of Stevens–Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2016;96:525–529. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa Y, Ueta M, Fukuoka H, Inatomi T, Yokota I, Teramukai S, et al. Long-term progression of ocular surface disease in Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Cornea. 2020;39:745–753. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000002263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa Y, Ueta M, Nishigaki H, Kinoshita S, Ikeda T, Sotozono C. Predictive biomarkers for the progression of ocular complications in chronic Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Sci Rep. 2020;10:18922. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-76064-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]