Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the most common form of dementia, currently affects 40–50 million people worldwide. Despite the extensive research into amyloid β (Aβ) deposition and tau protein hyperphosphorylation (p-tau), an effective treatment to stop or slow down the progression of neurodegeneration is missing. Emerging evidence suggests that ferroptosis, an iron-dependent and lipid peroxidation-driven type of programmed cell death, contributes to neurodegeneration in AD. Therefore, how to intervene against ferroptosis in the context of AD has become one of the questions addressed by studies aiming to develop novel therapeutic strategies. However, the underlying molecular mechanism of ferroptosis in AD, when ferroptosis occurs in the disease course, and which ferroptosis-related genes are differentially expressed in AD remains to be established. In this review, we summarize the current knowledge on cell mechanisms involved in ferroptosis, we discuss how these processes relate to AD, and we analyze which ferroptosis-related genes are differentially expressed in AD brain dependant on cell type, disease progression and gender. In addition, we point out the existing targets for therapeutic options to prevent ferroptosis in AD. Future studies should focus on developing new tools able to demonstrate where and when cells undergo ferroptosis in AD brain and build more translatable AD models for identifying anti-ferroptotic agents able to slow down neurodegeneration.

Keywords: neurodegeneration, iron dysregulation, glutathione, lipid peroxidation, amyloid β

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most prevalent age-related neurodegenerative disorder, affecting over 44 million people worldwide (Gaugler et al., 2016). In AD, formation of amyloid β (Aβ) plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) are associated with progressive cortical and hippocampal neuronal dysfunction and death (Dugger and Dickson, 2017). Many cell death mechanisms have been studied in AD pathology. The aggregation of Aβ was linked with caspase-9 and caspase-3-dependant apoptosis in neurons (Obulesu and Lakshmi, 2014), autophagy deficiency (Li and Sun, 2017), necrosis (Tanaka et al., 2020) and microglia-dependant activation of inflammasome pathway (Heneka et al., 2018). Despite extensive research into main hallmarks and molecular pathways of cell death in AD, many degenerative processes cannot be explained by these mechanisms alone, resulting in failure of over 200 AD drugs trials aiming at these targets over the past decade (Yiannopoulou et al., 2019).

In addition to apoptosis and necrosis, ferroptosis, an iron dependent and lipid-peroxidation driven cell death (Dixon, 2017), seems to be associated with AD (Hambright et al., 2017). Ferroptosis, the process increasing with aging (Zhou et al., 2020), is morphologically, genetically, and biochemically different from other types of cell death (Dixon et al., 2012). Its hallmarks, such as increased iron levels and oxidative stress, have been long noted in the AD brain (Praticò et al., 2001; Praticò and Sung, 2004; Castellani et al., 2007; Derry et al., 2020). It has been shown that formation of Aβ plaques and NFTs is related to iron overload in AD models and post mortem tissue (Yamamoto et al., 2002; Peters et al., 2018). Moreover, iron levels positively correlate with cognitive decline in human subjects (Ayton et al., 2017), and glutathione peroxidase (GPx4, also known as GPX4), the critical regulator of ferroptosis, is protective in AD mice model (Yoo et al., 2010).

Human genome-wide association studies (GWAS) support these results by showing a relation between the risk of developing AD and GPX4 polymorphism (Karch et al., 2016; da Rocha et al., 2018). Moreover, PSEN1/2 mutations identified in Alzheimer patients affected the hypoxic response in mouse embryonic fibroblasts by regulating hypoxia inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α), a driver of vulnerability to ferroptosis in cancer (Kaufmann et al., 2013; Zou et al., 2019). These results suggest that higher risk of developing AD is associated with deregulation of ferroptosis-related proteins, and thus ferroptosis inhibitors may have a therapeutic potential in AD (Weiland et al., 2019). However, the underlying mechanism of ferroptosis in AD, and whether ferroptosis happens at the onset, during or as a consequence of AD remains to be established.

Our aim is to examine the potential of ferroptosis inhibition as a therapeutic strategy for AD. We will first recapitulate ferroptosis pathway and its relation to AD, identify which ferroptosis-related genes are differentially expressed in AD and lastly, discuss the therapeutic options to prevent ferroptosis in AD.

Processes Involved in the Underlying Pathway of Ferroptosis

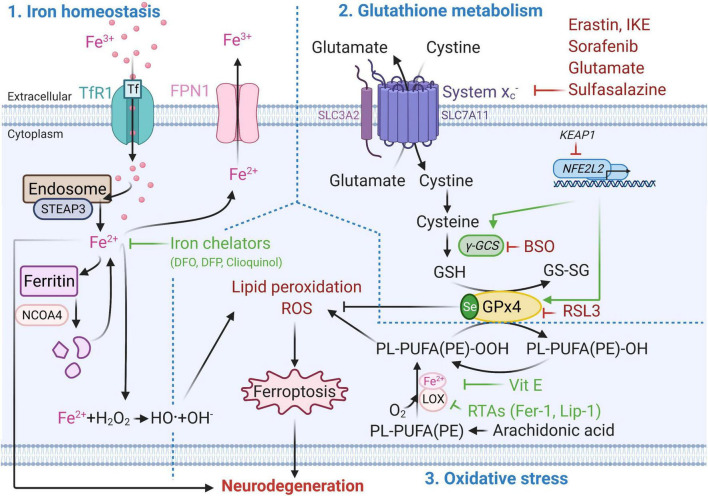

Ferroptosis mechanism can be divided into three parts: (1) iron homeostasis, (2) glutathione (GSH) metabolism and (3) oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation (Figure 1). Disruption of one or more of these mechanisms can induce lipid peroxidation-driven ferroptotic cell death.

FIGURE 1.

Molecular mechanisms of ferroptotic cell death. Metabolic pathways such as iron metabolism (left), cysteine and glutathione metabolism (top right), and polyunsaturated fatty acid metabolism (bottom right) play an essential role in the ferroptotic pathway. Well established ferroptosis inducers and inhibitors and their mode of action are depicted in red and green respectively. BSO, Buthionine sulphoximine; DFO, Deferoxamine; DFP, Deferiprone; Fe2 +, Ferrous iron; Fe3 +, Ferric iron; FPN1, Ferroportin; GPx4, Glutathione peroxidase 4; GSH, Glutathione (reduced glutathione form); GS-SG, Glutathione disulfide (oxidized glutathione form); Keap1, Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1, LOX, Lipoxygenase; NCOA4, Nuclear receptor co-activator 4; NFE2L2, nuclear factor E2 related factor 2 encoding for Nrf2; PL-PUFA(PE)-OH, Polyunsaturated-fatty-acids (phosphatidylethanolamine)-reduced; PL-PUFA(PE)-OOH, Polyunsaturated-fatty-acid-containing-phospholipid hydroperoxides; ROS, Reactive oxygen species; RSL3, (1S,3R)-methyl-2-(2-chloroacetyl)-2,3,4,9-tetrahydro-1-[4-(methoxycarbonyl)phenyl]-1H-pyrido [3,4-b]indole-3-carboxylic acid; RTAs, Radical-trapping antioxidants; Se, Selenocysteine; STEAP3, Six-Transmembrane Epithelial Antigen Of Prostate 3; xCT subunit of system xc–, Glutamate/cystine antiporter system; TfR1, Transferrin 1 receptor; Vit E, Vitamin E; γ-GCS, Gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase. This figure was created using Biorender.

Iron Homeostasis

Iron homeostasis plays a key role in ferroptosis (Yan and Zhang, 2020). Iron can enter the cell via transferrin 1 receptor (TfR1, also known as TFR1) and be reduced from ferric (Fe3+) to ferrous (Fe2+) form via metalloreductase STEAP3 in the endosome (Zhang et al., 2012). In this form, iron can be stored in ferritin, or exported from the cell via ferroportin (FPN1) (Chang, 2019). Ferritin degradation via the nuclear receptor coactivator 4 (NCOA4) contributes to ferroptosis by increasing the free intracellular iron levels (Hou et al., 2016). Excessive intracellular iron accumulation can lead to generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and oxidative stress via the Fenton reaction (Ward et al., 2014). Iron accumulation-induced ROS, such as superoxide anion (O2-•) and hydroxyl radical (•OH), possess an unpaired electron at their outer orbit which allows them to react with all cellular components including proteins, lipids and nucleic acid. This results in lipid peroxidation, oxidative damage to membranes and other lipid-containing molecules, and ultimately to cellular damage and ferroptotic cell death (Aprioku, 2013).

Glutathione Metabolism

On the other hand, inhibition of glutamate/cystine antiporter (system xc–, xc-, with xCT as the functional subunit of system xc–) and depletion of GSH cause inactivation of GPx4, the critical antioxidant enzyme and regulator of ferroptosis (Seibt et al., 2019). This can lead to ferroptotic cell death through increased lipid peroxidation and accumulation of ROS (Wang et al., 2020). GPx4 reduces hydroperoxides of polyunsaturated-fatty-acid-containing-phospholipids (PL-PUFA(PE)-OOH) to polyunsaturated-fatty-acids (phosphatidylethanol amine)-reduced (PL-PUFA(PE)-OH) (Seibt et al., 2019). GPx4 uses GSH as a reducing substrate and converts it into oxidized form, also referred to as glutathione disulphide (GS-SG) (Cozza et al., 2017). Apart from nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2, coded by NFE2L2 gene) (Habib et al., 2015), the xCT mRNA can be positively regulated by the activation of transcription factor 4 (ATF4) under oxidative stress (Sato et al., 2004), while its negative regulation by p53 results in cysteine deprivation and increased susceptibility to ferroptosis (Jiang et al., 2015).

Oxidative Stress and Lipid Peroxidation

Oxidative stress occurs due to the imbalance between generation of free radicals and the ability to neutralize or eliminate them through antioxidants (Birben et al., 2012). One of the main drivers of ferroptosis is ROS-mediated lipid peroxidation, which can result in oxidative stress (Kuang et al., 2020). Inhibition of GPx4 and decrease in GSH levels lead to activation of 12/15-lipoxygenase (12/15-LOX, which is the protein product of the ALOX15 gene). The association of Fe2+ with lipoxygenases (LOX, a dioxygenase containing non-heme iron) can lead to oxygenation of polyunsaturated-fatty-acids (PUFA), such as arachidonic acid present in phospholipids, and trigger lipid peroxidation-induced ferroptosis (Kagan et al., 2017). The LOX nomenclature is defined by the specific site of their oxygenation product: in humans there are six LOX isoforms 15-LOX-1, 15-LOX-2, 12-LOX-1, 12-LOX-2, E3-LOX, and 5-LOX, of which 12/15-LOX (15-LOX) are the most abundant. 12/15-LOX are considered as one of the key regulators of ferroptotic cell death (Yang et al., 2016; Kagan et al., 2017). Although, this has been supported by the findings that pharmacological inhibition of 15-LOX-1 exerts a cytoprotective effect (Seiler et al., 2008; Eleftheriadis et al., 2016), some off-target effects of lipoxygenase inhibitors have also been reported (Shah et al., 2018).

In addition to iron accumulation-induced generation of ROS, mitochondria also contribute to ROS production. Electrons leak from complex I and III of the electron transport chain (ETC) located on the inner membrane of mitochondria (Zhao et al., 2019). This can result in the formation of ROS such as O2-• and hydrogen peroxides (H2O2), and potentially can lead to loss of mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) (Gao et al., 2019). Reduced ΔΨm was associated with ferroptosis and involves different regulatory mechanisms than apoptosis (Kuang et al., 2020). GSH depletion-induced activation of 12/15-LOX can increase cytosolic Ca2+ via both (1) the import from the extracellular compartment and (2) release from mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum (Maher et al., 2018). Decrease in GSH levels can also lead to dysregulation of Ca2+ transport in and out of mitochondria by voltage dependant anion channels (VDAC) and mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter (MCU) (Zorov et al., 2014; DeHart et al., 2018). This results in mitochondrial Ca2+ overload and collapse of the mitochondrial function which activates Ca2+-dependant proteases (Zorov et al., 2014; DeHart et al., 2018; Marmolejo-Garza and Dolga, 2021). Consequently, ROS-induced transactivation of BH3 interacting-domain death agonist (BID) to mitochondria and Ca2+overload-induced translocation of apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF) from mitochondria to the nucleus causes the cell to die (Neitemeier et al., 2017). This caspase-independent process is accompanied by mitochondrial fragmentation and enlarged cristae (Dixon et al., 2012). The rescue of mitochondria (Jelinek et al., 2018), decrease of mitochondria-associated endoplasmic reticulum membranes (MAMs) interaction (Guo et al., 2019) and small conductance calcium-activated potassium (KCa2/SK) channel activation have the potential to protect from ferroptotic cell death (Krabbendam et al., 2020).

Contributions of Ferroptosis to Alzheimer’s Disease

Iron Homeostasis

Advanced age is associated with iron dysregulation affecting most of our organs (Xu et al., 2012; Picca et al., 2019). Many studies show that iron dysregulation can also contribute to AD pathology (Bush, 2013; Nuñez and Chana-Cuevas, 2018). With aging, iron deposits in the brain (Acosta-Cabronero et al., 2016), which can increase the formation of Aβ plaques (Becerril-Ortega et al., 2014) and tau hyperphosphorylation in AD transgenic mouse brain (Guo et al., 2013). Imaging and histological experiments support this by showing increased iron deposition in AD-specific brain regions (Altamura and Muckenthaler, 2009; Bush, 2013; Apostolakis and Kypraiou, 2017; Lee and Lee, 2019). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies revealed increased iron levels in the putamen, pulvinar thalamus, red nucleus, hippocampus, and temporal cortex of AD patients (Langkammer et al., 2014). Later, quantitative susceptibility mapping showed higher iron levels in caudate and putamen nucleus of AD patients than in controls. Interestingly, the increased iron level in the left caudate nucleus correlated with the degree of cognitive impairment (Du et al., 2018). Finally, higher iron levels in the frontal cortex were associated with AD severity (Bulk et al., 2018b). This evidence suggested that iron contributes to AD pathology and presented an important avenue for therapy development (Masaldan et al., 2019).

Glutathione Metabolism

Ferroptosis can be induced by compounds interfering with system xc–, such as erastin, which induces cysteine deprivation, GSH depletion, endoplasmic reticulum stress, and cell death (Dixon et al., 2012, 2014; Sato et al., 2018). System xc– can also be inhibited by adding small concentrations of sorafenib (Lachaier et al., 2014), glutamate (Jiang et al., 2020) and sulfasalazine (Yu et al., 2019) to the extracellular compartment. Inhibition of gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase (γ-GCS) by buthionine sulphoximine (BSO) results in GSH depletion and can lead to ferroptosis (Griffith, 1982). Irreversible and direct inhibition of GPx4 by the (1S,3R)-RSL3 (RSL3), causes the production of polyunsaturated-fatty-acid-containing-phospholipid hydroperoxides, which leads to lipid peroxidation and ferroptotic cell death (Liang et al., 2019). In addition to pharmacological compounds, genetic modifications targeting regulators of the system xc– can induce ferroptosis. The Gpx4BI-KO mouse was generated by a conditional deletion of Gpx4 in forebrain neurons by administration of tamoxifen. In this mouse model, 75–85% decrease of Gpx4 was shown to induce hippocampal neuronal loss, lipid peroxidation, neuroinflammation and spatial learning deficits (Hambright et al., 2017). Similarly, the knockout of Gpx1, facilitated memory impairment induced by β-Amyloid in mice (Joo et al., 2020). The Western blot analysis of AD post mortem brain tissue revealed enhanced expression of the light-chain subunit of the xCT (Ashraf et al., 2020). These results suggest that impaired GSH metabolism might play a role in ferroptosis during AD pathology (Ashraf et al., 2020).

Oxidative Stress and Lipid Peroxidation

The brain is the most vulnerable organ to oxidative stress. It represents only 2% of the body but uses 20% of the total oxygen supply (Sokoloff, 1999). Oxidative stress plays a key role in AD pathology by initiating the generation and enhancing of both Aβ plaques and hyperphosphorylation of Tau (p-Tau) (Huang et al., 2016; Nassireslami et al., 2016). Oxidative stress can be enhanced in AD via metal accumulation. In addition to iron, the Aβ precursor protein (APP) has a high affinity to binding zinc and copper at the N terminal metal-binding sites (Barnham et al., 2003). Additionally, high concentrations of these metals were also found in Aβ plaques in mouse and human brain (Plascencia-Villa et al., 2016; James et al., 2017). As copper is the potent mediator of •OH, and the binding of zinc leads to production of toxic Aβ and further uncontrolled zinc release, these metals can contribute to the increase of oxidative stress in AD (Strozyk et al., 2009). Post mortem tissue from AD patients shows higher levels of oxidized bases in the frontal, parietal and temporal lobes compared to control subjects (Wang et al., 2005), which correlates with imbalanced levels of copper, zinc and iron (Deibel et al., 1996). Other studies have shown higher level of lipid peroxidation, in diseased regions of AD brain compared to controls (Montine et al., 1998; Lovell et al., 2001; Bradley-Whitman and Lovell, 2015). These results support that oxidative stress might be an important factor contributing to the development and progression of AD (Zhao and Zhao, 2013).

Differential Expression of Ferroptosis-Related Genes in Alzheimer’s Disease

Many AD differentially expressed genes (DEGs) have been identified in animal and human studies. Using available RNAseq datasets of AD mouse models, AD patients and age-matched controls, we analyzed which of the 44 ferroptosis-related genes are differentially expressed in AD (Supplementary Table 1). To this end, we analyzed the expression of ferroptosis-related genes in one mouse [Alzmap (Chen et al., 2020)] and three human datasets of AD-DEGs [scREAD (Mathys et al., 2019), ACTA (Gerrits et al., 2021), AMPA-AD (Wan et al., 2020)]. All four datasets were available to the public and compared the gene expression between cell types, stages of disease progression and gender.

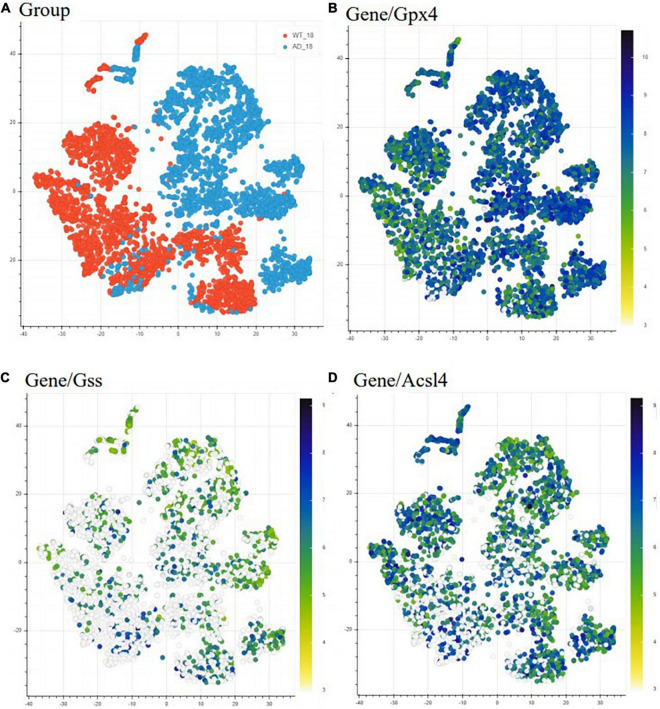

We first used the Alzmap gene retrieving function to make a qualitative assessment of the expression of three representative ferroptosis-related genes. We included (i) Gpx4, as it can suppress phospholipid peroxidation, an important process during ferroptosis, (ii) Gss, as it can facilitate the production of GSH, and (iii) Acsl4 for its role in supporting the incorporation of long PUFAs into lipid membranes, a process associated with ferroptosis (Figure 2). We choose t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (TSNE) statistical method to visualize the representative genes in a high-dimensional dataset (Figure 2). However, Alzmap website offers other modes of analysis and visualization tools such as the principal component analysis (PCA) and uniform manifold approximation and projections for dimension reduction (UMAP). The distribution and visualization of the chosen genes might render different output since these methods of visualization and reduction tools are based on specific clustering algorithms, i.e., unsupervised linear dimensionality reduction and data visualization technique for very high dimensional data for PCA, while t-SNE is based on a non-linear statistical method, calculating the similarity probability score in a low dimensional space. Therefore, visualization of genes could appear to render various outcomes. The alterations observed in the ferroptosis-related genes generated by Alzmap are purely based on a qualitative assessment. These data can be freely accessible on the https://alzmap.org/website.

FIGURE 2.

Differential expression of ferroptosis related genes in AD mice model compared to WT mice. Heatmap representing the difference in expression of ferroptosis-related genes between 18 months old WT (orange) and AD mice (light blue) (A). The heatmap depicts gene expression from low/white to high/dark blue. Each point indicates one spatial transcriptomic spot defining one tissue domain on the slide. Glutathione peroxidase 4 (Gpx4) is upregulated with pathology (B), while glutathione synthase (Gss) (C) and acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member (Acsl4) (D) are downregulated with the pathology. This data is freely accessible online, Alzmap (Chen et al., 2020).

In the Alzmap study, one left and one right hemisphere was collected for each experimental group and analyzed according to the spatial transcriptomic manual (Stockholm, Sweden) (Ståhl et al., 2016) using Fiji groovy script package (Chen et al., 2020). Our analysis revealed Gpx4 upregulation and Gss and Acsl4 downregulation in AppNL-G-F knock-in AD mice compared to WT mice. Although this analysis shows that these ferroptosis-related genes are differentially expressed in AppNL-G-F knock-in AD mice, it is known that downregulation of Gpx4 and upregulation of Acsl4 can induce ferroptosis (Dixon et al., 2012). Our observation from the TSNE analysis can be explained by cells trying to increase resistance against ferroptosis by increasing the generation of antioxidants (from the observation of increased Gpx4) and depleting the substrates for lipid peroxidation (as Acsl4 gene expression was found decreased) (Stockwell et al., 2017).

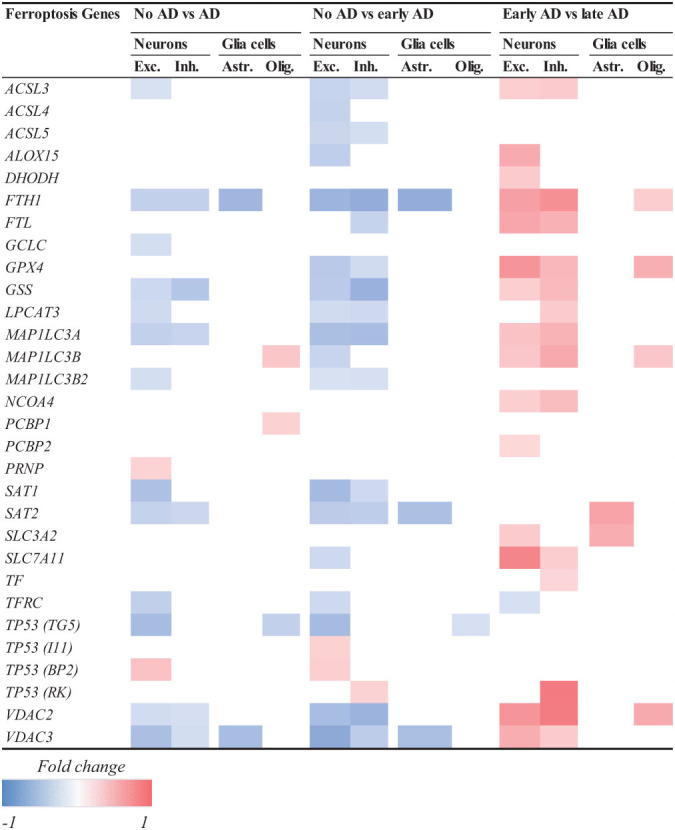

In the second study containing the scREAD dataset (Mathys et al., 2019), 48 participants were divided into early and late stage groups based on nine clinical pathological traits. Data was acquired by single-nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNAseq)-based differential expression analysis and assessed by Wilcoxon rank-sum test and false discovery rate (FDR) multiple-testing correction (Mathys et al., 2019). Our analysis revealed that ferroptosis-related genes in excitatory neurons from human brains are mostly downregulated at an early clinical stage of AD, while they are upregulated at a later clinical stage of the disease relative to early stage (Table 1). The same was observed with inhibitory neurons, astrocytes and glia cells. For instance, genes which are important for ferroptosis resistance [e.g., ACSL3, ferritin heavy chain (FTH1), GPX4, GSS and voltage-dependent anion channel 2 and 3 (VDAC2/3)] are downregulated in an early stage of AD pathology but upregulated at later AD stage. This could imply that ferroptosis already happens at early stages of the diseases. The shift from downregulation to upregulation at later stages can be explained by cells trying to compensate and rescue the ferroptotic cell death by increasing the expression of antioxidant proteins and enzymes. Furthermore, the observation that neurons show a higher number of ferroptosis DEGs in AD than astrocytes and oligodendrocytes suggests that ferroptosis affects neurons and glia cells differently (Kim et al., 2021). Although it seems from this dataset that ferroptosis gene expression changes primarily in neurons, it might be because glia cells were not primarily sorted out in this study. Therefore, next we analyzed a dataset that specifically looked at glia cells.

TABLE 1.

Log2-fold change of ferroptosis-related DEGs related to AD.

|

Decreased (blue) and increased (red) expression of ferroptosis-related genes in neurons (Exc, Excitatory and Inh, Inhibitory) and glia cells (Ast, Astrocytes and Olig, Oligodendrocytes) in AD brain. White space corresponds to unchanged gene expression. Participants were divided into early and late stage groups based on 9 clinico-pathological traits. Early AD is associated with decrease and late AD with increase in ferroptosis-related gene expression.

bACSL3, Long-chain-fatty-acid-CoA ligase 3; ACSL4, Long-chain-fatty-acid-CoA ligase 4; ACSL5, Long-chain-fatty-acid-CoA ligase 5; ALOX15, coding for arachidonate 15-lipoxygenase/15-lipoxygenase-1; DHODH, Dihydroorotate dehydrogenase; FTH1, Ferritin heavy chain; FTL, Ferritin light chain; GCLC, Glutamate-cysteine ligase catalytic subunit; GPx4, Glutathione peroxidase 4; GSS, Glutathione synthetase; LPCAT3, Lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 3; MAP1LC3A, Microtubule associated protein 1 light chain 3 Alpha; MAP1LC3B, Microtubule associated protein 1 light chain 3 Beta; MAP1LC3B2, Microtubule associated protein 1 light chain 3 Beta 2; NCOA4, Nuclear receptor coactivator 4; PCBP1, Poly(rC)-binding protein 1; PCBP2, Poly(rC)-binding protein 2; PRNP, prion protein; SAT1, Spermidine/spermine N1-acetyltransferase 1; SAT2, Spermidine/spermine N1-acetyltransferase 2; SLC11A2, Solute carrier family 11 member 2; TF, Transferrin; TFRC, Transferrin receptor; TP53BP2, Tumor protein p53 binding protein, 2; TP53I11, TP53 inducible protein; TP53RK, TP53 regulating kinase; TP53TG5, Tumor protein 53 target 5; VDAC2, Voltage-dependent anion channel 2; VDAC3, Voltage-dependent anion channel 3.

The criteria to determine if the change of the gene was significant included the false discovery rate (FDR)-corrected p < 0.01 in a two-sided Wilcoxon-rank sum test, absolute log2 > 0.25, and FDR-corrected P < 0.05 in a Poisson mixed model. Data was analyzed based on Mathys et al. (2019).

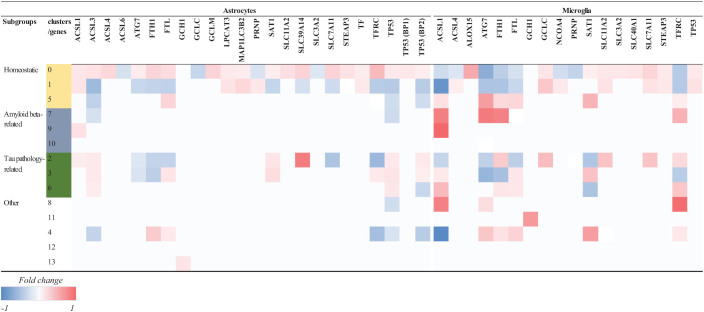

To further investigate how ferroptosis could affect glia cells in AD, we looked at the difference in expression of ferroptosis-related genes in microglia between control and AD brains containing only amyloid-β plaques in the occipital cortex (OC) and both amyloid-β and tau pathology in the occipitotemporal cortex (OTC) (Gerrits et al., 2021). In this study, the differential expression analysis was performed using a logistic regression and adjusted p-value below 0.05 was used to determine the significance (Gerrits et al., 2021). Microglia belonging to different subclusters (homeostatic, Aβ-related = AD1 and tau-related = AD2) showed changes in the expression of ferroptosis-related genes between AD and control subjects (Table 2). Microglia affected by Aβ pathology alone, or the combination of Aβ and tau pathology showed more DEGs than cells in the homeostatic subcluster. Microglia in the Aβ-related subcluster showed increase in the expression of ferroptosis-related genes, while microglia in tau pathology-related subcluster showed decrease in the expression of these genes. As the presence of tau pathology in OC is typical for later stages of the diseases, these results could suggest that there seem to be a difference between the expression of ferroptosis-related genes between early and late stages of AD. However, whether glia cells die via ferroptotic cell death at later stages of AD should be investigated further.

TABLE 2.

Log-fold change of ferroptosis-related DEGs in glia cells in AD.

Data in this table represent the Log-fold change per gene per subcluster. Decreased (blue) and increased (red) expression of ferroptosis-related genes in microglia nuclei isolated from CTR and AD brain tissues. Microglia were clustered into 13 subclusters, that were categorized as follows: 1. homeostatic, 2. Aβ-plaque associated (-AD1) and 3. Tau-associated (AD2), and other subclusters were related to pro-inflammatory responses, cellular stress and proliferation. White space corresponds to unchanged gene expression. ACSL, Long-chain-fatty-acid–CoA ligase; ALOX15, coding for Arachidonate 15-lipoxygenase/15-lipoxygenase-1; ATG, Autophagy related gene; FTH1, Ferritin heavy chain; FTL, Ferritin light chain; GCH1, Guanosine triphosphate cyclohydrolase-1; GCLC, Glutamate-cysteine ligase catalytic subunit; HMOX1, Heme oxygenase 1; NCOA4, Nuclear receptor coactivator 4; SAT1, Spermidine/spermine N1-acetyltransferase; SLC, Solute carrier family; STEAP3, STEAP3 Metalloreductase, TFRC, Transferrin receptor; TP53, tumor protein 53. The differential expression analysis was performed using a logistic regression from which we included ferroptosis-related genes with an adjusted p-value < 0.05. Differential gene expression results were extracted from supplementary table 2 from Gerrits et al. (2021).

ACSL, Long-chain-fatty-acid—CoA ligase; ALOX15, coding for Arachidonate 15-lipoxygenase/15-lipoxygenase-1; ATG, Autophagy related gene; FTH1, Ferritin heavy chain; FTL, Ferritin light chain; GCH1, Guanosine triphosphate cyclohydrolase-1; GCLC, Glutamate-cysteine ligase catalytic subunit; GCLM, Glutamate-cysteine ligase modifier subunit; LPCAT3, Lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 3; MAP1LC3B2, Microtubule associated protein 3 light chain 2 Beta; NCOA4, Nuclear receptor coactivator 4; PRNP, Prion protein; SAT1, Spermidine/spermine N1-acetyltransferase; SLC, Solute carrier family; STEAP3, STEAP3 Metalloreductase, TF, Transferrin; TFRC, Transferrin receptor; TP53, tumor protein 53.

The differential expression of genes was determined using a ‘chisq.test’ function in R and ‘anova_test’ function from the rstatix package (Moran’s I test, q-value < 0.05). Data was analyzed based on Gerrits et al. (2021).

Previous analysis of the whole brain human DEGs in AD revealed more AD-DEGs in women than men (Wan et al., 2020). To see whether this is also specifically true for ferroptosis-related genes, we analyzed the 44 ferroptosis-related genes in the AMPA-AD dataset where AD-DEGs were compared between genders (Table 3). The sample size included 478 AD (female: 318, male: 160) and 300 control (female: 148, male: 152) cases on which sex-stratified meta-analysis (Wan et al., 2020). Our analysis revealed three downregulated genes in both men and women while only GSS was downregulated in both. Only one gene, Cytochrome B-245 Beta Chain (CYBB), was upregulated in men while eleven genes were upregulated in women (Table 3). The analysis of the dataset available in this study indicates that like AD-DEGs, ferroptosis-related genes seem to be more differentially expressed in women than men. Finally, nine of the 44 ferroptosis-related genes were not differentially expressed in any of the analyzed datasets (Supplementary Table 1).

TABLE 3.

Comparison of ferroptosis-related DEGs in AD between genders.

| Men | Women | |

| Downregulated | GSS, SLC11A2, TFRC | GSS, MAP1LC3A, VDAC3 |

| Upregulated | CYBB | ACSL1, ALOX15B, FTL, HMOX1, NCOA4, SLC7A11, STEAP3, TF, TP53BP2, TP53I3, TP53RK |

ACSL1, Long-chain-fatty-acid-CoA ligase 1; ALOX15, Arachidonate 15-lipoxygenase/15-lipoxygenase-1; CYBB, Cytochrome B-245 Beta chain; FTL, Ferritin light chain; GSS, Glutathione synthetase; HMOX1, Heme oxygenase 1; MAP1LC3A, Microtubule associated protein 1 Light chain 3 Alpha; NCOA4, Nuclear receptor coactivator 4; SLC11A2, Solute carrier family 11 member 2; SLC7A11, Solute carrier family 7 member 11; STEAP3, STEAP3 Metalloreductase; TF, Transferrin; TFRC, Transferrin receptor; TP53BP2, Tumor protein p53 binding protein, 2; TP53I3, TP53 inducible protein; TP53RK, TP53 regulating kinase; VDAC3, Voltage-dependent anion channel 3.

The differentially expressed genes were determined as those with FDR P < 0.05 using weighted fixed/mixed effect linear models using the ‘voom-limma’ R package. Data was analyzed based on Wan et al. (2020).

Inhibition of Ferroptosis to Treat Alzheimer’s Disease

An increasing amount of literature suggests that anti-ferroptotic therapies may be efficient in AD (Ashraf et al., 2020; Li et al., 2020; Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Characteristics of included articles assessing therapeutic options to prevent ferroptosis in AD stratified by mechanisms involved in ferroptosis.

| Author (year) | AD model |

Compound | Administration |

Positive effect |

|||||||

| Species | Sex | Age (year) | Form | Time (months) | Amount | Aβ | pTau | Inflamation | Cognition | ||

| Iron homeostasis | |||||||||||

| Adlard et al., 2011 | Tg2576 mice | ♀ | 1.2 | PBT2 | o | 0.4 | 30 mg/kg/d | NR | NR | NR | Y |

| Adlard et al., 2008 | Tg2576 and APP/PS1 mice | ♂, ♀ | 1.5–1.8 | PBT2 | o | 0.4 | 30 mg/kg/d | Y | Y | NR | Y |

| Cherny et al., 2001 | Tg2576 mice | ♂, ♀ | 1.75 | PBT1 | o | 2 | 2 mg/kg/d | Y | NR | NR | Y |

| Crouch et al., 2011 | Aβ-induced SH−SY5Y cells | NA | NA | PBT2 | NA | 1 h | 10–20 μM | Y | NR | NR | NA |

| Fine et al., 2012 | TgP301L mice | NR | 0.7 | DFO | in | 5 | 3 × 2.4 mg/w | Y | NR | Y | Y |

| Grossi et al., 2009 | TgCRND8 mice | ♂, ♀ | 0.3 | PBT1 | o | 1.2 | 30 mg/kg/d | Y | NR | Y | Y |

| Guo et al., 2015 | APP/PS1 mice | ♂ | 0.5 | DFO | in | 3 | 200 mg/kg/2d | Y | NR | NR | NR |

| Guo et al., 2013 | APP/PS1 mice | ♂ | 0.5 | DFO | in | 3 | 200 mg/kg/2d | NR | Y | NR | NR |

| McLachlan et al., 1993 | AD patients | ♂, ♀ | 80 | DFO | im | 24 | 300 mg/d/5d/w | NR | NR | NR | Y |

| McLachlan et al., 1991 | AD patients | ♂, ♀ | 80 | DFO | im | 24 | 300 mg/d/5d/w | NR | NR | NR | Y |

| Ritchie et al., 2003 | AD patients | NR | NR | PBT1 | o | 8.3 | 300–750mg/d | Y | NR | NR | Y |

| Glutathione metabilism | |||||||||||

| Dumont et al., 2009 | Tg19959 mice | NR | 0.1 | CDDO-MA | o | 3 | 800 mg/kg chow | Y | NR | Y | Y |

| Fragoulis et al., 2017 | APP/PS1 mice | NR | 0.5 | Methysticin | o | 6 | 6 mg/kg/w | N | NR | Y | Y |

| Kanninen et al., 2009 | APP/PS1 mice | ♂ | 0.75 | LV-Nrf2 | icv | NA | 2-μL | Y | NR | Y | Y |

| Kerr et al., 2017 | ArcAβ42 flies | ♂, ♀ | 7d | LiCl | o | NA | 100 mM | Y | NR | NR | NR |

| Kim et al., 2013 | Aβ-induced ICR mice | ♂ | 0.4 | SFN | ip | 4d | 30mg/kg/d | N | NR | NR | Y |

| Lipton et al., 2016 | hAPP-J20 and 3xTg mice | NR | 0.3–0.5 | CA | in | 3 | 2 × 10mg/kg/w | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Nassireslami et al., 2016 | Aβ-induced wistar rats | ♂ | NR | SA | icv | NA | 5–100 nM | Y | NR | Y | Y |

| Wang et al., 2016 | APP/PS1 mice | ♂ | 0.3 | Dl-NBP | o | 5 | 60 mg/kg/d | Y | NR | NR | Y |

| Oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation | |||||||||||

| Adair et al., 2001 | AD patients | NR | NR | NAC | NR | 6 | 50 mg/kg/day | NR | NR | NR | N |

| Ates et al., 2020 | APPswe/PS1ΔE9 mice | ♂ | 0.75 | CMS121 | o | 3 | 34 mg/kg/d | NR | NR | Y | Y |

| Aβ-induced MC65 cells | NA | NA | CMS121 | NA | NR | NR | Y | NR | NR | NA | |

| Cong et al., 2019 | Aβ-induced SH−SY5Y cells | NA | NA | Chal.14a-c | NA | NA | 25μM | Y | NR | NR | NA |

| Fu et al., 2006 | Aβ-induced kunming mice | ♂ | 0.3 | NAC | ip | 7d | 50–200 mg/kg/d | Y | NR | NR | Y |

| McCaddon and Davies, 2005 | AD patients | ♂ | 65 | NAC | o | NR | 600 mg/d | NR | NR | NR | Y |

| Remington et al., 2009 | AD patients | NR | NR | NAC | o | 6–9 | 600 mg/d | NR | NR | NR | Y |

| Zhang et al., 2018 | P301S mice | ♀ | 0.4 | LA | ip | 2.3 | 3–10 mg/kg/d/5d/w | NR | Y | Y | Y |

| Zhang et al., 2017 | 3xTg mice | ♂, ♀ | 0.7 | Se-Met | o | 3 | 6 μg/ml | NR | Y | NR | Y |

| Sripetchwandee et al., 2016 | Wistar rats on HI diet | ♂ | 0.2 | DFO | ip | 2 | 75-mg/kg/d | Y | Y | NR | NR |

| NAC | 2 | 100 mg/kg/d | |||||||||

Articles are sorted in alphabetical order and from more to less recent.

(hAPP)-J20; mouse expressing the human amyloid precursor protein, 3xTg AD; mutant mouse with PS1M146V gene, APP/PS1; [B6C3-Tg(APPswe,PSEN1 dE9)85Dbo/J], APPswe/PS1ΔE9; transgenic mice express a mouse/human chimeric APPswe and a mutant human presinilin 1 (PS1ΔE9), ArcAβ42; Aβ42-expressing drosophila, CA; carnosic acid, Chal. 14a-c; Chalcones 14a, DFO, deferoxamine, FASN; fatty acid synthase, HI; high iron, LA; α-Lipoic acid, LV-Nrf2; human Nrf2 lentiviral vector, LiCl; lithium, N; no, NA; not applicable, NR; not reported, P301S; [B6C3-Tg (Prnp-MAPT*P301S) PS19 Vle/J], PBT1; clioquinol, SA; sodium arsenite, SFN; sulforaphane, SH-SY5Y; human neuroblastoma cells, Se-Met; selenomethionine, Tg2576; mouse line encoding human APP695 with Lys670-Asn and Met671-Leu mutations, Y; yes, d; day, icv; intracerebroventricular, im; intramuscular, in; intranasal, ip; intraperitoneal, o; oral, w; week, y; year.

Iron Homeostasis

Our transcriptomic analysis revealed that FTH1, component responsible for iron storage, is differentially expressed in early and late stages of AD. Furthermore, excessive iron deposition in specific brain areas contributes to AD pathology (Antharam et al., 2012; Moon et al., 2016). Therefore, an increased interest in the development of therapeutic strategies targeting iron has emerged in the past years. In animal models, DFO treatment decreased AD hallmarks, iron overload, iron-induced kinase activity [cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (CDK5), glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β)], mitochondrial dysfunction, synaptic loss, and neuronal damage (Fine et al., 2012; Guo et al., 2013, 2015; Sripetchwandee et al., 2016). DFO increased expression of transferrin receptor (TfR1) and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), leading to reduced iron-induced memory deficits in rodents (Fine et al., 2012; C. Guo et al., 2013, 2015; Sripetchwandee et al., 2016). In a clinical trial, DFO slowed down the progression of AD in patients (McLachlan et al., 1991, 1993). However, the dosing regimens need to be standardized before DFO could be implemented in the clinical setting (Farr and Xiong, 2021). In addition, to reduce DFO-related cytotoxicity and prolong its presence into circulation, new DFO component-containing nanogels were proposed as promising alternatives for iron-chelation in AD (Wang et al., 2018). Besides AD, DFO alone or co/treatment with ferrostatin (Fer-1, inhibitor of lipid peroxidation) also improved α-synuclein-induced pathology in a PD animal model (Febbraro et al., 2013). PBT1, a drug inhibiting zinc and copper ions from binding to Aβ, reduced Aβ deposition, attenuated astrogliosis and prevented memory impairment in AD animal models AD (Cherny et al., 2001; Grossi et al., 2009). In pilot-phase 2 clinical trial, PBT1 reduced Aβ plasma levels and, when looked specifically on severely affected AD patients, PBT1 was able to slow down the clinical decline (Ritchie et al., 2003). PBT2, a second-generation 8-hydroxyquinoline analog produced as a successor to clioquinol, induced GSK3β phosphorylation and prevented formation of Aβ in neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells (Crouch et al., 2011). In animal models of AD, PBT2 induced Aβ plaque degradation, decreased p-tau, rescued decreased spine density, increased brain-levels of BDNF and improved cognitive performance (Adlard et al., 2008, 2011). PBT2 was also assessed in a phase 2 clinical trial, where it lead to reduced levels of Aβ in cerebrospinal fluid and improved executive function compared to placebo (Lannfelt et al., 2008). However, PBT2 did not show any significant effect on cognition. Currently, deferiprone (DFP), a compound that alleviates symptoms related to PD pathology (Devos et al., 2014; Grolez et al., 2015; Gutbier et al., 2020), is evaluated a in phase 2 randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial with AD patients (NCT03234686). As previously reported, iron chelators can attenuate symptoms and slow down the progression of AD, which shows the potential for novel therapeutic approaches (Nuñez and Chana-Cuevas, 2018).

Glutathione Metabolism

The revealed differential gene expression of GPX4 and GSS suggests that modifying the expression or/and the activity of these gene-encoded proteins might be beneficial to treat AD. The expression of GPx4 can be directly upregulated by α-Lipoic acid (LA) (Zhang et al., 2018). LA treatment on P301S Tau transgenic mice enhanced the activity of system xc–, GPx4, superoxide dismutase 1 (Sod1), CDK5, GSK3β, TfR1 and FPN1 (Zhang et al., 2018). LA reduced the hippocampal levels of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), interleukin 1β (IL-1β), as well as the calcium (Ca2+) content, p-tau, calpain1 levels, and synaptic loss. As a result, these processes led to enhanced memory function (Zhang et al., 2018). Apart from LA, GPx4 can be activated in an indirect manner through Nrf2. Nrf2 plays an important role in neurodegeneration and ferroptosis by regulating a wide range of genes (Song and Long, 2020). In addition to the activation of GPx4 and GSH synthesis (Dodson et al., 2019), it can also affect the activity of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, GSH reductase, glutamate-cysteine ligase modifier subunit (GLCM), solute carrier family 7 member 11 (SLC7A11) and others as previously summarized by Song and Long (2020). Nrf2 can be upregulated using a human lentiviral vector or compounds such as sodium arsenite, triterpenoid, 2-cyano-3,12-dioxooleana-1,9-dien-28-oic acid-methylamide (CDDO-MA), dl-3-n-butylphthalide (DI-NBP), kavalactone methysticin, carnosic acid (CA) and sulforaphane (SFN). Nrf2 upregulation increased heme oxygenase-1 (HMOX1) levels and decreased AD hallmarks, hippocampal inflammation, oxidative stress, and Aβ-induced memory deficits in AD mouse models (Dumont et al., 2009; Kanninen et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2013; Lipton et al., 2016; Nassireslami et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2016; Fragoulis et al., 2017). Finally, genetic downregulation of Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1), the negative regulator of Nrf2, in ArcAβ42 flies, activated Nrf2, induced Aβ42 degradation, prevented neuronal toxicity in response to Aβ42 peptide, rescued neuronal-specific motor defects and increased life span (Kerr et al., 2017).

Altogether, these results suggest that inhibition of ferroptosis by targeting GSH metabolism is an important avenue for the development of new therapies for AD (Ashraf et al., 2020).

Oxidative Stress and Lipid Peroxidation

Lipid peroxidation represents an important hallmark of AD (Sultana et al., 2013), which was also supported by the observed differential expression of ACSL3 and 4 in the course of the pathology (Tables 1, 2). In many studies, oxidative stress was targeted to reduce neuronal damage and alleviate symptoms related to AD pathology. Anti-ferroptotic compounds that reduce oxidative stress include liproxstatin 1 (Lip-1) (inhibitor of ROS and lipid peroxidation), chalcones 14a-c (inhibitor of Aβ and lipid peroxidation), Selenomethionine (Se-Met) (inhibitor of lipid peroxidation), CMC121 (fatty acid synthase inhibitor), N-acetylcysteine (NAC) (free radical scavenger), Vitamin E (Vit E) and PD146176 (15-LOX-1 inhibitor). Studies using in vitro and in vivo models of AD have shown that targeting oxidative stress has a positive effect on neural degeneration, inflammation, Aβ1-42 aggregation, p-tau formation, GSH levels, iron overload, mitochondrial function, motor dysfunction and learning and memory (Fu et al., 2006; Sripetchwandee et al., 2016; Hambright et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2017; Cong et al., 2019; Ates et al., 2020). In concordance with these results, clinical trials have shown that NAC and co-treatment of NAC, Vit E and Se-Met improved behavioral symptoms, general well-being, and neuropsychiatric and cognitive scores of AD patients (Adair et al., 2001; McCaddon and Davies, 2005; Remington et al., 2009). Although Vitamin E treatment had no beneficial effect on patients with mild cognitive impairment (Marder, 2005), it was able to improve symptoms related to other neurodegenerative diseases such as PD (Taghizadeh et al., 2017) and cerebellar ataxia (Gabsi et al., 2001). Considering the lack of adverse events of these antioxidants, ferroptosis inhibition by targeting oxidative stress is a new promising therapeutic strategy for AD.

Discussion

Improved understanding of underlying mechanisms of ferroptosis in AD may lead to the development and application of anti-ferroptotic strategies to slow down or prevent AD progression (Han et al., 2020). Iron accumulation (Bulk et al., 2018a), lipid peroxidation (Majerníková et al., 2020) and mitochondrial dysfunction (Horowitz and Greenamyre, 2010), the main hallmarks of ferroptosis, are observed early in AD pathology, suggesting that targeting ferroptosis in AD may lead to the prevention of symptoms manifestation such as cognitive decline at advanced stages of AD.

Our analysis of DEGs in AD revealed that differential expression of ferroptosis-related genes in AD affects mostly neurons and that the changes observed in glia cells could be related to both tau phosphorylation and Aβ accumulation. This may explain the difference in the expression of ferroptotic markers between early (Aβ) and late (Aβ + p-tau) stages of AD. Even though this review has shed more light on the role of different brain cell types in ferroptosis during AD, whether ferroptosis in glia cells is related to later stages of the pathology should be investigated further.

While it is known that AD brain shows ferroptosis characteristics, it is unknown what is the causal relationship between AD and ferroptosis. Plasma ferritin increases with increasing age and Aβ deposition. Recent work on the inhibition of lipid peroxidation and iron accumulation in C. elegans revealed extended life- and health-span independently of other mechanisms (Jenkins et al., 2020). This evidence suggests that ferroptosis may be an age-related as well as disease-related process (Goozee et al., 2018; Larric et al., 2020). Therefore, ferroptosis inhibition may not only lead to slowing down the neurodegeneration but also contribute to longer health-span (Larric et al., 2020).

Iron dysregulation aggravates formation and aggregation of both Aβ and p-tau protein forming plaques and NFT respectively (Derry et al., 2020). Even though the link between ferroptosis and Aβ has been extensively studied, much less is known about its role in NFT formation. Therefore, future studies should try to investigate the role of ferroptosis in hyperphosphorylation of tau protein and formation of fibrillary tangles independently of Aβ pathology. This could be achieved by comparing the characteristics of ferroptotic cell death in AD with patients with primary age-related tauopathy (PART) (Crary et al., 2014).

Further research should also address the effect of ferroptosis on the interactions between different cell types in AD context. Although cell-cell interactions are dysregulated in AD brain (Henstridge et al., 2019), this feature of AD is often overlooked in in vitro studies. The brain-on-a-chip platform using induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) -derived neurons and glia from AD patients could allow a high throughput screening of the effect of anti-ferroptotic drugs in AD, while mimicking the cell-cell interactions in AD context (Trombetta-Lima et al., 2021). Moreover, this model is easily reproducible and thanks to the use of iPSCs from AD patients, also more translatable to humans compared to well-established animal models.

Conclusion

This review summarizes the evidence supporting the important role of ferroptosis in AD pathology and presents what is known about the targets for its inhibition for a potential treatment. Ferroptosis-related genes are differentially expressed in AD, supporting our hypothesis that ferroptosis inhibition could slow down the AD progression and memory decline, however, many questions remain unanswered. Developing new AD models allowing us to study how ferroptosis effects cell-cell interaction is needed to understand the causal relationship and timing of ferroptosis in AD. Future efforts should be directed toward developing detection techniques of ferroptosis in vivo and organizing large, randomized clinical trials of anti-ferroptotic drugs in early and late stages of AD progression.

Author Contributions

NM, AD, and WD designed the theme of the manuscript. NM contributed by writing all the sections and creating all tables and figures. AD and WD conducted critical revisions of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We thank Alejandro Marmolejo-Garza for the support on the transcriptomic analysis.

Funding

NM received a De Cock research grant and a fellowship from the Behavioural and Cognitive Neuroscience Graduate School, University Medical Centre Groningen. AD is the recipient of an Alzheimer Nederland grant (WE.03- 2018-04, Netherlands), and a Rosalind Franklin Fellowship co-funded by the European Union and the University of Groningen.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnagi.2021.745046/full#supplementary-material

References

- Acosta-Cabronero J., Betts M. J., Cardenas-Blanco A., Yang S., Nestor P. J. (2016). In vivo MRI mapping of brain iron deposition across the adult lifespan. J. Neurosci. 36 364–374. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1907-15.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adair J. C., Knoefel J. E., Morgan N. (2001). Controlled trial of N-acetylcysteine for patients with probable Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 57 1515–1517. 10.1212/WNL.57.8.1515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adlard P. A., Bica L., White A. R., Nurjono M., Filiz G., Crouch P. J., et al. (2011). Metal ionophore treatment restores dendritic spine density and synaptic protein levels in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS One 6:e17669. 10.1371/journal.pone.0017669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adlard P. A., Cherny R. A., Finkelstein D. I., Gautier E., Robb E., Cortes M., et al. (2008). Rapid Restoration of Cognition in Alzheimer’s Transgenic Mice with 8-Hydroxy Quinoline Analogs Is Associated with Decreased Interstitial Aβ. Neuron 59 43–55. 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altamura S., Muckenthaler M. U. (2009). Iron toxicity in diseases of aging: Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease and atherosclerosis. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 16 879–895. 10.3233/JAD-2009-1010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antharam V., Collingwood J. F., Bullivant J. P., Davidson M. R., Chandra S., Mikhaylova A., et al. (2012). High field magnetic resonance microscopy of the human hippocampus in Alzheimer’s disease: Quantitative imaging and correlation with iron. NeuroImage 59 1249–1260. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.08.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apostolakis S., Kypraiou A. M. (2017). Iron in neurodegenerative disorders: Being in the wrong place at the wrong time? Rev. Neurosci. 28 893–911. 10.1515/revneuro-2017-0020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aprioku J. S. (2013). Pharmacology of free radicals and the impact of reactive oxygen species on the testis. J. Reproduct. Infertil. 14 158–172. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashraf A., Jeandriens J., Parkes H. G., So P. W. (2020). Iron dyshomeostasis, lipid peroxidation and perturbed expression of cystine/glutamate antiporter in Alzheimer’s disease: Evidence of ferroptosis. Redox Biol. 32:101494. 10.1016/j.redox.2020.101494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ates G., Goldberg J., Currais A., Maher P. (2020). CMS121, a fatty acid synthase inhibitor, protects against excess lipid peroxidation and inflammation and alleviates cognitive loss in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Redox Biol. 36:101648. 10.1016/j.redox.2020.101648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayton S., Fazlollahi A., Bourgeat P., Raniga P., Ng A., Lim Y. Y., et al. (2017). Cerebral quantitative susceptibility mapping predicts amyloid-β-related cognitive decline. Brain 140 2112–2119. 10.1093/brain/awx137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnham K. J., McKinstry W. J., Multhaup G., Galatis D., Morton C. J., Curtain C. C., et al. (2003). Structure of the Alzheimer’s disease amyloid precursor protein copper binding domain. A regulator of neuronal copper homeostasis. J. Biol. Chem. 278 17401–17407. 10.1074/jbc.M300629200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becerril-Ortega J., Bordji K., Fréret T., Rush T., Buisson A. (2014). Iron overload accelerates neuronal amyloid-β production and cognitive impairment in transgenic mice model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 35 2288–2301. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.04.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birben E., Sahiner U. M., Sackesen C., Erzurum S., Kalayci O. (2012). Oxidative stress and antioxidant defense. World Allergy Organizat. J. 5 9–19. 10.1097/WOX.0b013e3182439613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley-Whitman M. A., Lovell M. A. (2015). Biomarkers of lipid peroxidation in Alzheimer disease (AD): an update. Arch. Toxicol. 89 1035–1044. 10.1007/s00204-015-1517-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulk M., Kenkhuis B., Van Der Graaf L. M., Goeman J. J., Natté R., Van Der Weerd L. (2018b). Postmortem T2*-Weighted MRI Imaging of Cortical Iron Reflects Severity of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 65 1125–1137. 10.3233/JAD-180317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulk M., Abdelmoula W. M., Nabuurs R. J. A., van der Graaf L. M., Mulders C. W. H., Mulder A. A., et al. (2018a). Postmortem MRI and histology demonstrate differential iron accumulation and cortical myelin organization in early- and late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 62 231–242. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2017.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush A. I. (2013). The metal theory of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 33(Suppl. 1), S277–S281. 10.3233/JAD-2012-129011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellani R. J., Moreira P. I., Liu G., Dobson J., Perry G., Smith M. A., et al. (2007). Iron: The redox-active center of oxidative stress in Alzheimer disease. Neurochem. Res. 32 1640–1645. 10.1007/s11064-007-9360-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y. (2019). Cellulat iron metabolism and regulation. Brain Iron Metabol. CNS Dis. 1173 21–32. 10.1007/978-981-13-9589-5_2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W. T., Lu A., Craessaerts K., Pavie B., Sala Frigerio C., Corthout N., et al. (2020). Spatial Transcriptomics and In Situ Sequencing to Study Alzheimer’s Disease. Cell 182 976.e–991.e. 10.1016/j.cell.2020.06.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherny R. A., Atwood C. S., Xilinas M. E., Gray D. N., Jones W. D., McLean C. A., et al. (2001). Treatment with a copper-zinc chelator markedly and rapidly inhibits β-amyloid accumulation in Alzheimer’s disease transgenic mice. Neuron 30 665–676. 10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00317-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cong L., Dong X., Wang Y., Deng Y., Li B., Dai R. (2019). On the role of synthesized hydroxylated chalcones as dual functional amyloid-β aggregation and ferroptosis inhibitors for potential treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 166 11–21. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.01.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cozza G., Rossetto M., Bosello-Travain V., Maiorino M., Roveri A., Toppo S., et al. (2017). Glutathione peroxidase 4-catalyzed reduction of lipid hydroperoxides in membranes: The polar head of membrane phospholipids binds the enzyme and addresses the fatty acid hydroperoxide group toward the redox center. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 112 1–11. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2017.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crary J. F., Trojanowski J. Q., Schneider J. A., Abisambra J. F., Abner E. L., Alafuzoff I., et al. (2014). Primary age-related tauopathy (PART): a common pathology associated with human aging. Acta Neuropathol. 128 755–766. 10.1007/s00401-014-1349-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crouch P. J., Savva M. S., Hung L. W., Donnelly P. S., Mot A. I., Parker S. J., et al. (2011). The Alzheimer’s therapeutic PBT2 promotes amyloid-β degradation and GSK3 phosphorylation via a metal chaperone activity. J. Neurochem. 119 220–230. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07402.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Rocha T. J., Silva Alves M., Guisso C. C., de Andrade F. M., Camozzato A., de Oliveira A. A., et al. (2018). Association of GPX1 and GPX4 polymorphisms with episodic memory and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci. Lett. 666 32–37. 10.1016/j.neulet.2017.12.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeHart D. N., Fang D., Heslop K., Li L., Lemasters J. J., Maldonado E. N. (2018). Opening of voltage dependent anion channels promotes reactive oxygen species generation, mitochondrial dysfunction and cell death in cancer cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 148 155–162. 10.1016/j.bcp.2017.12.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deibel M. A., Ehmann W. D., Markesbery W. R. (1996). Copper, iron, and zinc imbalances in severely degenerated brain regions in Alzheimer’s disease: Possible relation to oxidative stress. J. Neurol. Sci. 143 137–142. 10.1016/S0022-510X(96)00203-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derry P. J., Hegde M. L., Jackson G. R., Kayed R., Tour J. M., Tsai A. L., et al. (2020). Revisiting the intersection of amyloid, pathologically modified tau and iron in Alzheimer’s disease from a ferroptosis perspective. Prog. Neurobiol. 184:101716. 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2019.101716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devos D., Moreau C., Devedjian J. C., Kluza J., Petrault M., Laloux C., et al. (2014). Targeting chelatable iron as a therapeutic modality in Parkinson’s disease. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 21 195–210. 10.1089/ars.2013.5593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon S. J. (2017). Ferroptosis: bug or feature? Immunol. Rev. 277 150–157. 10.1111/imr.12533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon S. J., Lemberg K. M., Lamprecht M. R., Skouta R., Zaitsev E. M., Gleason C. E., et al. (2012). Ferroptosis: An iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell 149 1060–1072. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon S. J., Patel D., Welsch M., Skouta R., Lee E., Hayano M., et al. (2014). Pharmacological inhibition of cystine-glutamate exchange induces endoplasmic reticulum stress and ferroptosis. ELife 3:e02523. 10.7554/eLife.02523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodson M., Castro-Portuguez R., Zhang D. D. (2019). NRF2 plays a critical role in mitigating lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis. Redox Biol. 23:101107. 10.1016/j.redox.2019.101107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du L., Zhao Z., Cui A., Zhu Y., Zhang L., Liu J., et al. (2018). Increased Iron Deposition on Brain Quantitative Susceptibility Mapping Correlates with Decreased Cognitive Function in Alzheimer’s Disease. ACS Chemical Neurosci. 9 1849–1857. 10.1021/acschemneuro.8b00194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugger B. N., Dickson D. W. (2017). Pathology of neurodegenerative diseases. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 9:a028035. 10.1101/cshperspect.a028035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumont M., Wille E., Calingasan N. Y., Tampellini D., Williams C., Gouras G. K., et al. (2009). Triterpenoid CDDO-methylamide improves memory and decreases amyloid plaques in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurochem. 109 502–512. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.05970.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eleftheriadis N., Poelman H., Leus N. G. J., Honrath B., Neochoritis C. G., Dolga A., et al. (2016). Design of a novel thiophene inhibitor of 15-lipoxygenase-1 with both anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective properties. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 122, 786–801. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.07.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farr A. C., Xiong M. P. (2021). Challenges and Opportunities of Deferoxamine Delivery for Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease, Parkinson’s Disease, and Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Mol. Pharmaceut. 18 593–609. 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.0c00474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Febbraro F., Andersen K. J., Sanchez-Guajardo V., Tentillier N., Romero-Ramos M. (2013). Chronic intranasal deferoxamine ameliorates motor defects and pathology in the α-synuclein rAAV Parkinson’s model. Exp. Neurol. 247 45–58. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2013.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine J. M., Baillargeon A. M., Renner D. B., Hoerster N. S., Tokarev J., Colton S., et al. (2012). Intranasal deferoxamine improves performance in radial arm water maze, stabilizes HIF-1α, and phosphorylates GSK3β in P301L tau transgenic mice. Exp. Brain Res. 219 381–390. 10.1007/s00221-012-3101-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fragoulis A., Siegl S., Fendt M., Jansen S., Soppa U., Brandenburg L. O., et al. (2017). Oral administration of methysticin improves cognitive deficits in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Redox Biol. 12 843–853. 10.1016/j.redox.2017.04.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu A. L., Dong Z. H., Sun M. J. (2006). Protective effect of N-acetyl-l-cysteine on amyloid β-peptide-induced learning and memory deficits in mice. Brain Res. 1109 201–206. 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.06.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabsi S., Gouider-Khouja N., Belal S., Fki M., Kefi M., Turki I., et al. (2001). Effect of vitamin E supplementation in patients with ataxia with vitamin E deficiency. Eur. J. Neurol. 8 477–481. 10.1046/j.1468-1331.2001.00273.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao M., Yi J., Zhu J., Minikes A. M., Monian P., Thompson C. B., et al. (2019). Role of Mitochondria in Ferroptosis. Mol. Cell 73 354.e–363.e. 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.10.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler J., James B., Johnson T., Scholz K., Weuve J. (2016). 2016 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2 459–509. 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerrits E., Brouwer N., Kooistra S. M., Woodbury M. E., Vermeiren Y., Lambourne M., et al. (2021). Distinct amyloid-β and tau-associated microglia profiles in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 141 681–696. 10.1007/s00401-021-02263-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goozee K., Chatterjee P., James I., Shen K., Sohrabi H. R., Asih P. R., et al. (2018). Elevated plasma ferritin in elderly individuals with high neocortical amyloid-β load. Mol. Psychiatry 23 1807–1812. 10.1038/mp.2017.146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith O. W. (1982). Mechanism of action, metabolism, and toxicity of buthionine sulfoximine and its higher homologs, potent inhibitors of glutathione synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 257 13704–13712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grolez G., Moreau C., Sablonnière B., Garçon G., Devedjian J. C., Meguig S., et al. (2015). Ceruloplasmin activity and iron chelation treatment of patients with Parkinson’s disease. BMC Neurol. 6:74. 10.1186/s12883-015-0331-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossi C., Francese S., Casini A., Rosi M. C., Luccarini I., Fiorentini A., et al. (2009). Clioquinol decreases amyloid-β burden and reduces working memory impairment in a transgenic mouse model of alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 17 423–440. 10.3233/JAD-2009-1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo C., Wang P., Zhong M. L., Wang T., Huang X. S., Li J. Y., et al. (2013). Deferoxamine inhibits iron induced hippocampal tau phosphorylation in the Alzheimer transgenic mouse brain. Neurochem. Int. 62 165–172. 10.1016/j.neuint.2012.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo C., Zhang Y. X., Wang T., Zhong M. L., Yang Z. H., Hao L. J., et al. (2015). Intranasal deferoxamine attenuates synapse loss via up-regulating the P38/HIF-1α pathway on the brain of APP/PS1 transgenic mice. Front. Aging Neurosci. 7:104. 10.3389/fnagi.2015.00104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X., Lin H., Liu J., Yao P. (2019). Quercetin Protects Hepatocyte from Ferroptosis by Depressing Mitochondria-reticulum Interaction Through PERK Downregulation in Alcoholic Liver (P06-056-19). Curr. Dev. Nutrit. 2019:19. 10.1093/cdn/nzz031.p06-056-19 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gutbier S., Kyriakou S., Schildknecht S., Ückert A. K., Brüll M., Lewis F., et al. (2020). Design and evaluation of bi-functional iron chelators for protection of dopaminergic neurons from toxicants. Arch. Toxicol. 94 3105–3123. 10.1007/s00204-020-02826-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habib E., Linher-Melville K., Lin H. X., Singh G. (2015). Expression of xCT and activity of system xc- are regulated by NRF2 in human breast cancer cells in response to oxidative stress. Redox Biol. 5 33–42. 10.1016/j.redox.2015.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hambright W. S., Fonseca R. S., Chen L., Na R., Ran Q. (2017). Ablation of ferroptosis regulator glutathione peroxidase 4 in forebrain neurons promotes cognitive impairment and neurodegeneration. Redox Biol. 12 8–17. 10.1016/j.redox.2017.01.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han C., Liu Y., Dai R., Ismail N., Su W., Li B. (2020). Ferroptosis and Its Potential Role in Human Diseases. Front. Pharmacol. 11:239. 10.3389/fphar.2020.00239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heneka M. T., McManus R. M., Latz E. (2018). Inflammasome signalling in brain function and neurodegenerative disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 19 610–621. 10.1038/s41583-018-0055-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henstridge C. M., Hyman B. T., Spires-Jones T. L. (2019). Beyond the neuron–cellular interactions early in Alzheimer disease pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 20 94–108. 10.1038/s41583-018-0113-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz M. P., Greenamyre J. T. (2010). Mitochondrial iron metabolism and its role in neurodegeneration. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 20(Suppl. 2), S551–S568. 10.3233/JAD-2010-100354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou W., Xie Y., Song X., Sun X., Lotze M. T., Zeh H. J., et al. (2016). Autophagy promotes ferroptosis by degradation of ferritin. Autophagy 12 1425–1428. 10.1080/15548627.2016.1187366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W. J., Zhang X., Chen W. W. (2016). Role of oxidative stress in Alzheimer’s disease. Biomed. Rep. 4 519–522. 10.3892/br.2016.630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James S. A., Churches Q. I., De Jonge M. D., Birchall I. E., Streltsov V., McColl G., et al. (2017). Iron, Copper, and Zinc Concentration in Aβ Plaques in the APP/PS1 Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease Correlates with Metal Levels in the Surrounding Neuropil. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 8 629–637. 10.1021/acschemneuro.6b00362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jelinek A., Heyder L., Daude M., Plessner M., Krippner S., Grosse R., et al. (2018). Mitochondrial rescue prevents glutathione peroxidase-dependent ferroptosis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 117 45–57. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins N. L., James S. A., Salim A., Sumardy F., Speed T. P., Conrad M., et al. (2020). Changes in ferrous iron and glutathione promote ferroptosis and frailty in aging caenorhabditis elegans. ELife 9:e56580. 10.7554/eLife.56580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L., Kon N., Li T., Wang S. J., Su T., Hibshoosh H., et al. (2015). Ferroptosis as a p53-mediated activity during tumour suppression. Nature 520 57–62. 10.1038/nature14344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang T., Cheng H., Su J., Wang X., Wang Q., Chu J., et al. (2020). Gastrodin protects against glutamate-induced ferroptosis in HT-22 cells through Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway. Toxicol. Vitro 2020:104715. 10.1016/j.tiv.2019.104715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joo E., Yoon S., Chung H., Sharma N., Trong B., Sung N., et al. (2020). Glutathione Peroxidase - 1 Knockout Facilitates Memory Impairment Induced by β - Amyloid (1 – 42) in Mice via Inhibition of PKC βII - Mediated ERK Signaling; Application with Glutathione Peroxidase - 1 Gene - Encoded Adenovirus Vector. Neurochem. Res. 2020:0123456789. 10.1007/s11064-020-03147-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan V. E., Mao G., Qu F., Angeli J. P. F., Doll S., Croix C. S., et al. (2017). Oxidized arachidonic and adrenic PEs navigate cells to ferroptosis. Nat. Chem. Biol. 13 81–90. 10.1038/nchembio.2238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanninen K., Heikkinen R., Malm T., Rolova T., Kuhmonen S., Leinonen H., et al. (2009). Intrahippocampal injection of a lentiviral vector expressing Nrf2 improves spatial learning in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 106 16505–16510. 10.1073/pnas.0908397106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karch C. M., Ezerskiy L. A., Bertelsen S., Goate A. M., Albert M. S., Albin R. L., et al. (2016). Alzheimer’s disease risk polymorphisms regulate gene expression in the ZCWPW1 and the CELF1 loci. PLoS One 11:e0148717. 10.1371/journal.pone.0148717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann M. R., Barth S., Konietzko U., Wu B., Egger S., Kunze R., et al. (2013). Dysregulation of hypoxia-inducible factor by presenilin/γ-secretase loss-of-function mutations. J. Neurosci. 33 1915–1926. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3402-12.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr F., Sofola-Adesakin O., Ivanov D. K., Gatliff J., Gomez Perez-Nievas B., Bertrand H. C., et al. (2017). Direct Keap1-Nrf2 disruption as a potential therapeutic target for Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS Genet. 13:e1006593. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. V., Kim H. Y., Ehrlich H. Y., Choi S. Y., Kim D. J., Kim Y. S. (2013). Amelioration of Alzheimer’s disease by neuroprotective effect of sulforaphane in animal model. Amyloid 20 7–12. 10.3109/13506129.2012.751367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S., Kim Y., Kim S. E., An J. (2021). Ferroptosis-Related Genes in Neurodevelopment and Central Nervous System. Biology 10:35. 10.3390/biology10010035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krabbendam I. E., Honrath B., Dilberger B., Iannetti E. F., Branicky R. S., Meyer T., et al. (2020). SK channel-mediated metabolic escape to glycolysis inhibits ferroptosis and supports stress resistance in C. elegans. Cell Death Dis. 11:263. 10.1038/s41419-020-2458-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuang F., Liu J., Tang D., Kang R. (2020). Oxidative Damage and Antioxidant Defense in Ferroptosis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020:1–10. 10.3389/fcell.2020.586578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachaier E., Louandre C., Godin C., Saidak Z., Baert M., Diouf M., et al. (2014). Sorafenib induces ferroptosis in human cancer cell lines originating from different solid tumors. Anticancer Res. 34 6417–6422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langkammer C., Ropele S., Pirpamer L., Fazekas F., Schmidt R. (2014). MRI for iron mapping in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurodegenerat. Dis. 13 189–191. 10.1159/000353756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lannfelt L., Blennow K., Zetterberg H., Batsman S., Ames D., Harrison J., et al. (2008). Safety, efficacy, and biomarker findings of PBT2 in targeting Aβ as a modifying therapy for Alzheimer’s disease: a phase IIa, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 7 779–786. 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70167-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larric J. W., Larric J. W., Mendelsoh A. R. (2020). Contribution of Ferroptosis to Aging and Frailty. Rejuvenat. Res. 23 434–438. 10.1089/rej.2020.2390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. H., Lee M. S. (2019). Brain iron accumulation in atypical parkinsonian syndromes: In vivo MRI evidences for distinctive patterns. Front. Neurol. 10:74. 10.3389/fneur.2019.00074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Cao F., Yin H., I, Huang Z. J., Lin Z. T., Mao N., et al. (2020). Ferroptosis: past, present and future. Cell Death Dis. 11:2. 10.1038/s41419-020-2298-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q., Sun M. (2017). The role of autophagy in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Syst. Integrat. Neurosci. 3 1–6. 10.15761/jsin.1000172 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liang C., Zhang X., Yang M., Dong X. (2019). Recent Progress in Ferroptosis Inducers for Cancer Therapy. Adv. Mater. 31:e1904197. 10.1002/adma.201904197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipton S. A., Rezaie T., Nutter A., Lopez K. M., Parker J., Kosaka K., et al. (2016). Therapeutic advantage of pro-electrophilic drugs to activate the Nrf2/ARE pathway in Alzheimer’s disease models. Cell Death Dis. 7:389. 10.1038/cddis.2016.389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovell M. A., Xie C., Markesbery W. R. (2001). Acrolein is increased in Alzheimer’s disease brain and is toxic to primary hippocampal cultures. Neurobiol. Aging 22 187–194. 10.1016/S0197-4580(00)00235-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher P., van Leyen K., Dey P. N., Honrath B., Dolga A., Methner A. (2018). The role of Ca2+ in cell death caused by oxidative glutamate toxicity and ferroptosis. Cell Calcium 70 47–55. 10.1016/j.ceca.2017.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majerníková N., Jia J., Andrea Y. (2020). CuATSM PET to diagnose age - related diseases: a systematic literature review. Clin. Translat. Imaging 8 449–460. 10.1007/s40336-020-00394-w [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marder K. (2005). Vitamin E and donepezil for the treatment of mild cognitive impairment. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 5 337–338. 10.1007/s11910-005-0056-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmolejo-Garza A., Dolga A. M. (2021). PEG out through the pores with the help of ESCRTIII. Cell Calcium 97:102422. 10.1016/j.ceca.2021.102422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masaldan S., Belaidi A. A., Ayton S., Bush A. I. (2019). Cellular senescence and iron dyshomeostasis in alzheimer’s disease. Pharmaceuticals 12:93. 10.3390/ph12020093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathys H., Davila-Velderrain J., Peng Z., Gao F., Mohammadi S., Young J. Z., et al. (2019). Single-cell transcriptomic analysis of Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 570 332–337. 10.1038/s41586-019-1195-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaddon A., Davies G. (2005). Co-administration of N-acetylcysteine, vitamin B12 and folate in cognitively impaired hyperhomocysteinaemic patients. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 20 998–1000. 10.1002/gps.1376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLachlan D. R. C., Kruck T. P. A., Kalow W., Andrews D. F., Dalton A. J., Bell M. Y., et al. (1991). Intramuscular desferrioxamine in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet 337 1304–1308. 10.1016/0140-6736(91)92978-B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLachlan D. R., Smith W. L., Kruck T. P. (1993). Desferrioxamine and alzheimer’s disease: Video home behavior assessment of clinical course and measures of brain aluminum. Therapeut. Drug Monitor. 15 602–607. 10.1097/00007691-199312000-00027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montine T. J., Markesbery W. R., Morrow J. D., Roberts L. J. (1998). Cerebrospinal fluid F2-isoprostane levels are increased in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann. Neurol. 44 410–413. 10.1002/ana.410440322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon Y., Han S. H., Moon W. J. (2016). Patterns of Brain Iron Accumulation in Vascular Dementia and Alzheimer’s Dementia Using Quantitative Susceptibility Mapping Imaging. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 51 737–745. 10.3233/JAD-151037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nassireslami E., Nikbin P., Amini E., Payandemehr B., Shaerzadeh F., Khodagholi F., et al. (2016). How sodium arsenite improve amyloid β-induced memory deficit? Physiol. Behav. 163 97–106. 10.1016/j.physbeh.2016.04.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neitemeier S., Jelinek A., Laino V., Hoffmann L., Eisenbach I., Eying R., et al. (2017). BID links ferroptosis to mitochondrial cell death pathways. Redox Biol. 12 558–570. 10.1016/j.redox.2017.03.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuñez M. T., Chana-Cuevas P. (2018). New perspectives in iron chelation therapy for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases. Pharmaceuticals 11:109. 10.3390/ph11040109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obulesu M., Lakshmi M. J. (2014). Apoptosis in Alzheimer’s Disease: An Understanding of the Physiology, Pathology and Therapeutic Avenues. Neurochem. Res. 39 2301–2312. 10.1007/s11064-014-1454-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters D. G., Pollack A. N., Cheng K. C., Sun D., Saido T., Haaf M. P., et al. (2018). Dietary lipophilic iron alters amyloidogenesis and microglial morphology in Alzheimer’s disease knock-in APP mice. Metallomics 10 426–443. 10.1039/c8mt00004b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picca A., Mankowski R. T., Kamenov G., Anton S. D., Manini T. M., Buford T. W., et al. (2019). Advanced Age Is Associated with Iron Dyshomeostasis and Mitochondrial DNA Damage in Human Skeletal Muscle. Cells 8:1525. 10.3390/cells8121525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plascencia-Villa G., Ponce A., Collingwood J. F., Josefina Arellano-Jiménez M., Zhu X., Rogers J. T., et al. (2016). High-resolution analytical imaging and electron holography of magnetite particles in amyloid cores of Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Rep. 6 1–12. 10.1038/srep24873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Praticò D., Sung S. (2004). Lipid Peroxidation and Oxidative imbalance: Early functional events in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 6 171–175. 10.3233/JAD-2004-6209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Praticò D., Uryu K., Leight S., Trojanoswki J. Q., Lee V. M. Y. (2001). Increased lipid peroxidation precedes amyloid plaque formation in an animal model of alzheimer amyloidosis. J. Neurosci. 21 4183–4187. 10.1523/jneurosci.21-12-04183.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remington R., Chan A., Paskavitz J., Shea T. B. (2009). Efficacy of a vitamin/nutriceutical formulation for moderate-stage to later-stage alzheimer’s disease: A placebo-controlled pilot study. Am. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. Dement. 24 27–33. 10.1177/1533317508325094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie C. W., Bush A. I., Mackinnon A., Macfarlane S., Mastwyk M., MacGregor L., et al. (2003). Metal-Protein Attenuation with Iodochlorhydroxyquin (Clioquinol) Targeting Aβ Amyloid Deposition and Toxicity in Alzheimer Disease: A Pilot Phase 2 Clinical Trial. Arch. Neurol. 60 1685–1691. 10.1001/archneur.60.12.1685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato H., Nomura S., Maebara K., Sato K., Tamba M., Bannai S. (2004). Transcriptional control of cystine/glutamate transporter gene by amino acid deprivation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 325 109–116. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato M., Kusumi R., Hamashima S., Kobayashi S., Sasaki S., Komiyama Y., et al. (2018). The ferroptosis inducer erastin irreversibly inhibits system xc- and synergizes with cisplatin to increase cisplatin’s cytotoxicity in cancer cells. Sci. Rep. 8:968. 10.1038/s41598-018-19213-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seibt T. M., Proneth B., Conrad M. (2019). Role of GPX4 in ferroptosis and its pharmacological implication. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 133 144–152. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiler A., Schneider M., Förster H., Roth S., Wirth E. K., Culmsee C., et al. (2008). Glutathione Peroxidase 4 Senses and Translates Oxidative Stress into 12/15-Lipoxygenase Dependent- and AIF-Mediated Cell Death. Cell Metabol. 8 237–248. 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]