Abstract

Background

Surgical excision remains the cornerstone of simultaneous diagnosis and treatment of suspicious skin lesions, and the scalp is a high-risk area for skin cancers due to increased cumulative lifetime ultraviolet (UV) exposure. Due to the inelasticity of scalp skin, most excisions with predetermined margins require reconstruction with skin grafting.

Methods

A retrospective single-centre cohort study was performed of all patients undergoing outpatient local anaesthetic scalp skin excision and skin graft reconstruction in the Plastic Surgery Department at Addenbrookes Hospital over a 20-month period between 1 April 2017 and 1 January 2019. In total, 204 graft cases were collected. Graft reconstruction techniques included both full-thickness and split-thickness skin grafts. Statistical analysis using Z tests were used to determine which skin grafting technique achieved better graft take.

Results

Split-thickness skin grafts had a statistically significant (P = 0.01) increased average take (90%) compared to full-thickness skin grafts (72%). Using a foam tie-over dressing on the scalp led to a statistically significant (P = 0.000036) increase in skin graft take, from 38% to 79%.

Conclusion

In skin graft reconstruction of scalp defects after skin cancer excision surgery, split skin grafts secured with foam tie-over dressings are associated with superior outcomes compared to full-thickness skin grafts or grafts secured with sutures only.

Keywords: Scalp, skin graft, split, full, reconstruction, tie-over

Keywords: Lay Summary

Introduction

Excisional procedures for suspected skin malignancy are often performed in an outpatient local anaesthetic (OPLA) setting. Depending on the anatomical location of the skin lesion and if tension-free skin closure cannot be achieved, skin grafts can be harvested to reconstruct a defect that would otherwise take weeks to months to heal by secondary intention.

A recent European study showed that the scalp is a very common anatomical site for suspected skin neoplasms and accounted for 8.9% of all non-melanomatous skin cancers (NMSCs). 1 Many NMSCs are managed surgically, and excised with a predetermined peripheral margin and an appropriate deep resection margin, often down to the periosteum on the scalp. After excision of scalp NMSCs, it is common for skin grafts to be utilised owing to the relative inelasticity of scalp skin precluding direct closure. Larger defects may require further reconstructive methods such as tissue expansion, local flaps or free flaps. 2

Skin grafts can be either split-thickness skin grafts (STSG), where the epidermis is taken with a thin layer of the dermis, or full-thickness skin grafts (FTSG), where the epidermis is taken with the entire thickness of the dermis. 3 Further comparison of STSGs versus FTSGs is available in Table 1 below.

Table 1.

Comparison of split versus full-thickness skin grafts: comparison of relative advantages/disadvantages of FTSG vs. STSG in scalp defect reconstruction.

| FTSG | STSG |

|---|---|

| Ability to be harvested with a scalpel only, no specialist equipment or training required | Harvested by means of a manual handheld knife (e.g. Watson or Braithwaite knife) or a powered (air-driven or electric) dermatome |

| Only able to harvest small grafts, which are able to be closed primarily | Ability to harvest larger grafts, with the added flexibility of improving coverage area further using meshing techniques |

| Primary closure of donor site, improving healing time | Delayed donor site healing as primary closure not possible – possibility of complications such as over-granulation, and healing time depends on quality of patient skin at donor site |

| Likely improved cosmetic outcome – decreased depth step from edge of excision onto graft bed | Poorer cosmesis due to thinner graft in deep defect |

| Donor site selection limited by skin laxity to allow direct closure (typically, supraclavicular, post/pre-auricular) | Fewer restrictions on donor sites - large areas available on thigh, calves, upper arm etc. |

| Difficult to use in contoured defects | Can be draped over contours to adhere well onto the surface |

Although STSGs are known to generally have a better take rate than FTSGs, a variation of surgeon familiarity with the equipment required to harvest a STSG (Watson blade/Braithwaite knife) and a lack of battery-powered dermatomes in the OPLA setting mean that technical limitations to STSG reconstruction exist and examination of whether this hurdle affects patient outcome is indicated. The aim of this study was to determine whether there was a difference in healing outcomes if post-excision scalp defects were reconstructed using split-thickness or full-thickness skin grafts.

Methods and materials

Plastic surgery outpatient local anaesthetic operating lists were retrospectively analysed from 1 April 2017 to 1 January 2019 inclusive, and all patients who received skin graft reconstruction were included in this study. Exclusion criteria were cases of two-stage, complex reconstructions, re-excisions (due to involved margins), reconstructions via local flaps and main theatre cases. Electronic operation notes and histology reports were analysed and used to determine the total scalp skin defect area. Patients were routinely followed up in the Plastic Surgery Unit, a nurse-led dressings clinic where graft take and any complications were documented, initially at one week postoperatively and as necessary thereafter. These electronic records and photographs were also assessed regarding outcomes including postoperative complications and donor site healing. Statistical significance testing was performed using the Z test (to compare graft take, full vs. split thickness), the chi-square test (when evaluating whether foam dressings increased graft take) and the T test (to evaluate time taken for donor site to heal, full vs. split thickness grafts). STROBE guidelines were adhered to.

Results

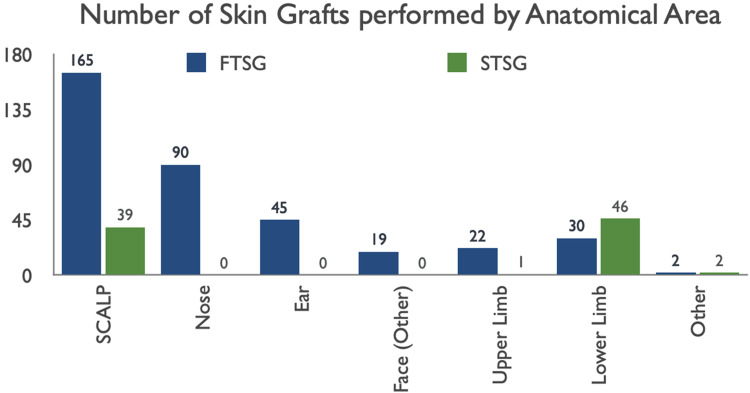

The total number of skin grafts on all anatomical areas performed in 20 months was 461, with scalp skin grafts making up 204 (44%) of these. The total graft cohort sizes were 165 FTSGs and 39 STSGs (Figure 1). The patients receiving scalp skin graft reconstruction had a mean age of 80.3 years. Of these patients, 28% had biopsy-proven skin malignancy (i.e. tissue diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma [BCC] or squamous cell carcinoma [SCC]). Other patients were assessed in clinic and excision biopsy was directly indicated. Overall, FTSGs were favoured in all anatomical areas, apart from the leg, where STSGs were preferred.

Figure 1.

Scalp skin grafts made up 204 out of 461 of total grafts performed in 18 months. The only other anatomical areas where split skin grafts made up a decent proportion of total grafts were the leg, foot and ankle.

Mean skin lesion diameter was 17.4 mm, with a mean predetermined peripheral margin of 5.5 mm. Patients receiving FTSGs had a decreased mean elliptical defect area of 537 mm2 compared to patients receiving STSGs at 990 mm2 (Table 2). This also corresponded with a decreased mean lesion diameter (15.8 mm) compared to patients receiving STSGs (24.1 mm). Of FTSGs, 67% were harvested from the neck, but other donor sites included the pre-auricular area and the upper limb. All STSGs were harvested from the thigh.

Table 2.

Comparison of lesion size and defect area when selecting reconstruction with FTSG or STSG: use of STSGs was favoured when the lesion diameter was bigger and the subsequent soft-tissue deficit area was increased.

| FTSG | STSG | |

|---|---|---|

| Average defect dimensions (length × width mm) | 27.6 × 23.4 | 37.9 × 31.2 |

| Mean defect area (ellipse mm2) | 537 | 990 |

| Mean lesion diameter (mm) | 15.8 | 24.1 |

Patients were followed up in a nurse-led outpatient dressings clinic one week after their operation as standard for a graft check. Donor sites were checked if the dressings had loosened or fallen off naturally concurrently. If graft take was even and definitive, further care of the graft site was passed onto community/practice nurses. If graft take was in doubt, a clinical photograph was taken for electronic documentation, an acute doctor review may be indicated and future appointments at the dressings clinic were booked at weekly intervals to recheck the graft. Electronic nursing documentation records regarding details of graft checks were collated. STSGs had a statistically significant (P = 0.0107 when using one-tailed Z test) increased rate of take (90%) compared to FTSGs (72%) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Percentage graft take, graft failure, and grafts lost to follow-up (LTFU) of FTSG vs STSG.

| FTSG | STSG | |

|---|---|---|

| Grafts taken (%) | 72 | 90 |

| Grafts failed (%) | 22 | 8 |

| Grafts LTFU (%) | 6 | 2 |

STSGs had a statistically significant increase in average take (90%) compared to FTSGs (72%) (P = 0.0107). The failure rate of STSGs was statistically significantly decreased (8%) compared to FTSGs (22%) (P = of 0.0217).

FTSG, full thickness skin graft; LTSU, Lost to Follow-up; STSG, split-thickness skin graft.

The failure rate of STSGs were found to be statistically significantly decreased (8%) compared to FTSGs (22%) with a P value of 0.0217 (again, using one-tailed Z test). It was also found that a greater proportion of patients who had had FTSGs (6%) as opposed to STSGs (2%) had inconclusive one-week graft checks, where nursing staff found it difficult to assess for routine clinical signs of graft take (namely mechanical and visual integration without evidence of necrosis or epidermolysis). Sometimes, patients’ grafts did not seem uniformly taken or lost, and were discharged to the community at the one-week mark due to a lack of immediate clinical concern, with the knowledge that they could always be easily re-referred by community teams if problems arose. They were labelled as “Lost to Follow Up” (LTFU). All cases were consequently seen in doctor-led clinics for their histological diagnosis and outcome (at 4–8 weeks), with all patients having recorded good scalp wound healing (although, due to the long follow-up timeframe without weekly surveillance, graft breakdown and consequent healing via secondary intention may well be the predominant healing mechanism). Unfortunately, due to the lack of district/practice nursing notes available at clinic, it became a slightly less reliable patient-reported measure about whether graft healing or secondary intention was the most predominant mechanism, so that outcome was not formally collected in this study.

All patients were discharged from the nurse-led dressings clinic at or before the four-week mark. It was found that at the halfway stage (two weeks), 24 patients who had received FTSGs had yet to have their grafts declared taken or failed compared to the cohort of STSGs, where all patient grafts had been followed up and documented as taken/failed (Figure 2). Thus, it can be further hypothesised that FTSGs either take longer to heal or take longer to declare than STSGs. Common documented complications of FTSGs were collections/haematomas under the graft (5 patients), and of STSGs were infection (1 patient). All STSG and FTSG were documented to be scalpel-fenestrated.

Figure 2.

Rate, week on week, of FTSG vs. STSG declared ‘taken or ‘failed’. Grey line indicates rate of documentation of successful graft take. Red line indicates rate of documented graft failure. STSGs seem to be documented as taken or failed quicker than FTSGs, with a smaller proportion lost to follow-up. FTSG, full-thickness skin graft; STSG, split-thickness skin graft.

The use of foam tie-over dressings overlying the skin grafts was also scrutinised. The foam tie-over dressing technique was defined in our data as a disc of sterile theatre foam, with a non-adhesive dressing underneath and immediately abutting the graft, that was sutured in place to provide both compression and protection from shearing forces. OPLA electronic operation notes from the patients getting STSGs or FTSGs were read, and surgeon dressing preference was recorded. Two popular techniques were simple quilting sutures (no foam dressing, often with a simple non-adhesive dressing and a layer of gauze on top) or a foam tie-over. Using a foam tie-over on the scalp statistically significantly (P = 0.000036 when using the chi-square test) increased skin graft take from 38% to 79% (Table 4).

Table 4.

The effect of foam tie-over dressings on graft take. Using a foam tie-over dressing increased underlying skin graft take from 38% to 79% (P value = 0.000036).

| No. of taken grafts | No. of failed grafts | No. grafts LTFU | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Foam | 147 (79) | 29 (16) | 10 (5) |

| No Foam | 7 (39) | 10 (55) | 1 (6) |

Values are given as n (%).

LTFU, lost to follow-up.

Mean documented time for donor sites to heal in patients who had repeated nurse-led clinic follow up for FTSGs was 1.5 weeks, and for STSGs was 1.9 weeks. The time of 1.9 weeks is statistically significantly longer (P = 0.021 in a two-sample t-test) than 1.5 weeks.

Discussion

Scalp reconstruction using skin grafting is a commonly performed procedure after excision of malignant skin lesions. Possibly due to ease of process (i.e. does not require specialised equipment or working off a distant donor site) and a decreased need for technique training, FTSGs are currently favoured in our department compared to STSGs, but perhaps increased surgeon education and practice using harvesting tools will help to improve the proportion in the future.

In this study, we see that STSGs offer an increased rate of easily observed graft take compared to FTSGs; however, as expected, their donor sites take longer to heal (via secondary intention) than FTSGs (via primary intention). A suggested method for speeding up STSG donor site healing is to replant the excess split-thickness graft back onto the donor site to seed nests of epidermis (a process termed back-grafting by Goverman et al.). 4 Once healed, this can sometimes have poor cosmetic outcomes, but in the senior author's experience, certainly allows for swifter healing in elderly patients, who may be more willing to accept the cosmetic risk.

Foam dressings with tie-overs were found to significantly increase the rate of graft take for both FTSGs and STSGs in this study, which contradicts previous data collected by Dhillon et al. 5 who showed a 6% graft failure with foam dressings (referred to as “pressure dressings”) compared to 0% without skin grafts to the head, neck and face. The main factors behind these statistics are the prevention of underlying collections or haematomas due to ease of fenestration, and the foam dressing secured in place to surrounding scalp skin aids graft adherence and minimises the chance of graft shearing. Further research could compare human fibrinogen sealants to conventional tie-over dressings to evaluate which aids graft adherence more and hence hastens graft take; however, owing to the expense of these sealants, they are often not financially viable to be used in such large quantities.

Although not common in our patient cohort, healing via secondary intention is sometimes considered for the scalp. Snow et al. 6 suggested that the complication rates for second intention healing were only 5.4%, but their study was focused on patients who had had Mohs excisions, which would theoretically leave behind more tissue with granulation potential than an excision down to the periosteum (which is often indicated to gain an adequate deep margin for a skin cancer). Reconstruction of other large operative sites (i.e. donor site for free radial forearm) have shown no statistical significance when comparing split versus full thickness skin grafts7,8; however, it is suggested that STSGs have increased donor site morbidity (scarring, pain). It must be acknowledged that a recent paper by Hilton et al. showed a 90%–100% graft take rate of 78.6% in FTSGs, compared to 82.1% in STSGs on scalp reconstruction after excision of scalp skin malignancies, which is statistically equivocal. 9

Limitations on this study include the retrospective nature of the study versus a true double-blind prospective study. Subjectivity of graft take is partially mitigated by the extensive use of clinical photography in the plastic surgery clinic, and, where possible, during data collection for this paper, recorded graft take was correlated against objective photographic evidence. The variety of seniority of clinicians (both nurse specialists and surgical colleagues) who reviewed grafts for their percentage of take could also add a further subjectivity to the results.

Conclusion

Although patient factors, such as suitability of a thigh donor site (oedematous legs or poor-quality thin skin, for example, could feasibly have an extended donor site healing period that may impact on quality of life), should be considered on a case-by-case basis, the results of this study show that STSGs are preferential compared to FTSGs for scalp reconstruction, and, additionally, a foam tie-over dressing is also recommended for optimal wound healing.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Max Byrne, final year medical student at the University of Cambridge, who helped to collect the data required for publication.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Luxi Sun https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9505-2983

How to cite this article

Sun L and Patel AJK. Outcomes of split versus full-thickness skin grafts in scalp reconstruction in outpatient local anaesthetic theatre. Scars, Burns & Healing, Volume 7, 2021. DOI: 10.1177/20595131211056542.

References

- 1.Eismann N, Waldmann A, Geller A, et al. Non-melanoma skin cancer incidence and impact of skin cancer screening on incidence. J Invest Dermatol 2014; 134: 43–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lin S, Hanasono M, Skoracki R. Scalp and calvarial reconstruction. Semin Plast Surg 2008; 22: 281–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adams D, Ramsay M. Grafts in dermatologic surgery: review and update on full- and split-thickness skin grafts, free cartilage grafts, and composite grafts. Dermatol Surg 2006; 31: 1055–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goverman J, Kraft CT, Fagan S, et al. Back grafting the split-thickness skin graft donor site. J Burn Care Res 2017; 38: e443–e449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dhillon M, Carter CP, Morrison J, et al. A comparison of skin graft success in the head & neck with and without the Use of a pressure dressing. J Maxillofac Oral Surg 2015; 14: 240–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Snow S, Stiff M, Bullen R, et al. Second-intention healing of exposed facial-scalp bone after Mohs surgery for skin cancer: review of ninety-one cases. J Am Acad Dermatol 1994; 31: 450–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zuidam J, Michiel MD, Coert Jet al. et al. Closure of the donor site of the free radial forearm flap: a comparison of full-thickness graft and split-thickness skin graft. Ann Plast Surg 2005; 55: 612–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davies WJ, Wu C, Sieber D, et al. A comparison of full and split thickness skin grafts in radial forearm donor sites. J Hand Microsurg 2011; 3: 18–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hilton C, Hölmich L. Full- or split-thickness skin grafting in scalp surgery? Retrospective case series. World J Plast Surg 2019; 8: 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]