Abstract

Background:

Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) is not only a common aetiology but also accompanying comorbidity of non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis (bronchiectasis). However, the association between GORD and the disease burden of bronchiectasis has not been well evaluated. Our study aimed to evaluate whether GORD is associated with increased healthcare use and medical costs in patients with bronchiectasis.

Methods:

We analyzed the data from 44,119 patients with bronchiectasis using a large representative Korean population-based claim database between 2009 and 2017. We compared the healthcare use [outpatient department (OPD) visits and emergency room (ER) visits/hospitalizations] and medical costs in patients with bronchiectasis according to the presence or absence of GORD.

Results:

The prevalence of GORD in patients with bronchiectasis tended to increase during the study period, especially in the 50s and older population. GORD was associated with increased use of all investigated healthcare resources in patients with bronchiectasis. Healthcare use including OPD visits (mean 47.6/person/year versus 30.0/person/year), ER visits/hospitalizations (mean 1.7/person/year versus 1.1/person/year), and medical costs (mean 3564.5 Euro/person/year versus 2198.7 Euro/person/year) were significantly higher in bronchiectasis patients with GORD than in those without GORD (p < 0.001 for all). In multivariable analysis, bronchiectasis patients with GORD showed 1.44-fold (95% confidence interval = 1.37–1.50) and 1.26-fold (95% confidence interval = 1.19–1.33) increased all-cause and respiratory-related ER visits/hospitalizations relative to those without GORD, respectively. After adjusting for potential confounders, the estimated total medical costs (mean 4337.3 versus 3397.4 Euro/person/year) and respiratory disease-related medical costs (mean 920.7 versus 720.2 Euro/person/year) were significantly higher in bronchiectasis patients with GORD than in those without GORD (p < 0.001 for both).

Conclusion:

In patients with bronchiectasis, GORD was associated with increased healthcare use and medical costs. Strategies to reduce the disease burden associated with GORD are needed in patients with bronchiectasis.

Keywords: bronchiectasis, gastrointestinal tract, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, health economics

Introduction

The disease burden of non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis (hereafter referred to as bronchiectasis) is substantial, with an increasing prevalence and incidence worldwide.1–3 Furthermore, disease burden in terms of healthcare use and mortality is significantly higher in patients with bronchiectasis than those without bronchiectasis.4–6 Accordingly, studies evaluating factors associated with increased disease burden in bronchiectasis are urgently needed.

Bronchiectasis-related comorbidities are contributors to increased disease burdens in patients with bronchiectasis; thus, appropriate management of bronchiectasis-related comorbidities is required to help reduce these burdens.7,8 Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) is a common comorbidity of bronchiectasis, affecting 19–79% of patients with bronchiectasis.9–12 GORD is associated with more symptoms, such as cough and sputum amount, reduced lung function, disease severity, and radiologic severity, as well as increased risk of exacerbation.10,12,13

However, few studies have evaluated the association between GORD and healthcare use and medical costs in patients with bronchiectasis. 12 South Korea provides universal health coverage for almost all Korean citizens. This method of coverage has the advantage of relatively easy assessment of healthcare use and associated medical costs. 14 We hypothesized that the disease burden, assessed by healthcare use, and medical costs would be higher in bronchiectasis patients with GORD than in those without GORD. To evaluate our hypothesis, we used a large representative population-based claims database from Korea, the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service-National Patient Sample (HIRA-NPS), in this study.

Methods

Study population

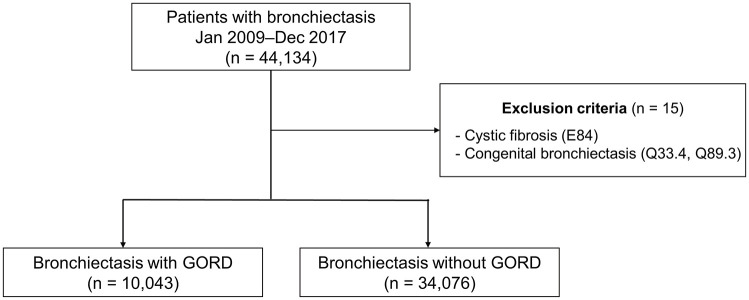

The HIRA-NPS is nationally representative and open to the public for research purposes. 15 The data are cross-sectional and composed of health insurance claims records in each year. The database includes approximately 1,400,000 data each year drawn by 3% stratified random sampling by age and sex from the entire population who had claims records for each year. More detailed information on HIRA-NPS was described in previous studies.11,16 We initially included 44,134 patients with bronchiectasis from January 2009 to December 2017 using the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10) diagnosis code J47. Of the 44,134 patients, we excluded 15 patients with cystic fibrosis (E84) or congenital bronchiectasis (Q33.4 and Q89.3). Consequently, 44,119 patients with bronchiectasis were included in the final analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study.

GORD, gastro-oesophageal reflux.

Exposure

The exposure of this study was the presence of GORD. GORD was defined when the following criteria were met: (1) ICD-10 code for GORD (K21) and (2) prescription of proton pump inhibitors for at least 2 weeks. 17

Outcomes

The outcomes were healthcare uses [outpatient department (OPD) visits, emergency room (ER) visits, or hospitalizations] and medical costs. The medical cost (patient out-of-pocket costs and payer costs) consisted of expenses associated with diagnostic tests, procedures, and treatments (e.g. examination, diagnostic tests, procedures, prescriptions, infection, and operation) covered by National Health Insurance. 18 Respiratory-related healthcare uses were defined as healthcare uses under ICD codes for respiratory diseases (J00–J99).

Covariables

We used the ICD-10 codes to define comorbidities. Pulmonary comorbidities consisted of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD; J42–J44, except J43.0 (unilateral emphysema)], asthma (J45–J46), pulmonary tuberculosis (TB; A15–A19), non-tuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease (NTM-PD; A31.0, A31.8, and A31.9), and lung cancer (C33–C34). Extrapulmonary comorbidities consisted of cerebrovascular disease (G45–G46, I60-I69, and H34.0), hypertension (I10–I15), angina or myocardial infarction (MI; I20, I21, I22, and I25.2), congestive heart failure (I43, I50, I09.9, I11.0, I25.5, I13.0, I13.2, I42.0, I42.5–I42.9, and P29.0), inflammatory bowel disease (K50–K51), diabetes mellitus (E10–E14), chronic kidney disease (N18), and connective tissue disease (M05, M06, M315, M32, M33, M34, M351, M353, and M360). Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) was calculated using a modified version consisting of 17 comorbidities. 19

Statistical analyses

We calculated the age-adjusted prevalence of GORD among patients with bronchiectasis by dividing the number of events by 100,000 persons/year. In addition, we compared healthcare uses and medical costs between bronchiectasis patients with GORD and those without GORD. All variables were categorized and compared using Pearson’s chi-square tests. Regarding medical costs, we provided real medical costs as well as estimated medical costs adjusted for potential confounders (age, sex, type of insurance, and CCI) using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA). A multivariable logistic regression model was used to assess the association between GORD and ER visits or hospitalizations among patients with bronchiectasis, with adjustment for age, sex, type of insurance, and CCI. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). All tests were two-tailed, and p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Prevalence of GORD in patients with bronchiectasis

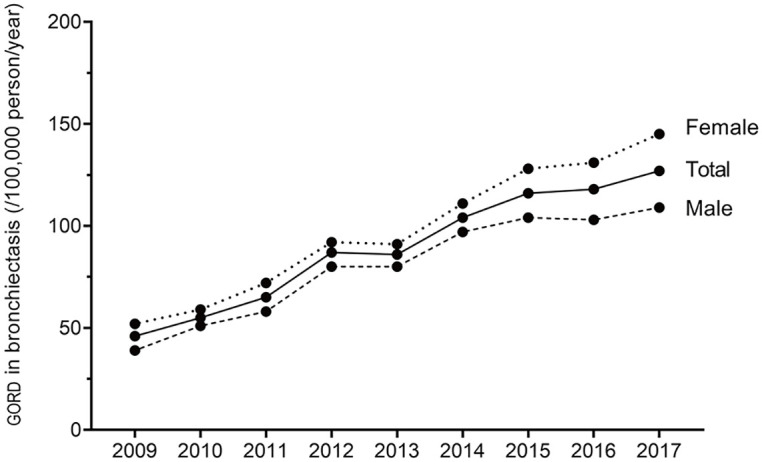

Of 44,119 patients with bronchiectasis, 29.5% had GORD. The age-adjusted prevalence of GORD in patients with bronchiectasis from 2009 to 2017 is described in Figure 2. The total prevalence of GORD in patients with bronchiectasis increased from 46/100,000 persons/year in 2009 to 127/100,000 persons/year in 2017. This prevalence of bronchiectasis in patients aged under 50 years of age was similar over the study periods. However, the prevalence of bronchiectasis showed an increasing trend in the 50s or older populations. The prevalence of bronchiectasis was substantially higher in females than in males over the study periods (p < 0.001 for each year).

Figure 2.

Age-adjusted prevalence of gastro-oesophageal reflux in patients with bronchiectasis. Data are expressed as numbers per 100,000 persons/year.

GORD, gastro-oesophageal reflux.

Characteristics of the population

The baseline characteristics of the study population are summarized in Table 1. The proportions of patients over 70 years (33.9% versus 30.5%, p < 0.001), female (56.5% versus 54.8%, p = 0.003), and those under medical aid (10.3% versus 7.0%, p < 0.001) were higher in bronchiectasis patients with GORD than in those without GORD. Among pulmonary comorbidities, the proportions of COPD (44.1% versus 35.7%), asthma (52.2% versus 42.1%), and lung cancer (4.5% versus 3.4%) were significantly higher in bronchiectasis patients with GORD than in those without GORD (p < 0.001 for all). However, there was no significant intergroup difference in the proportions of pulmonary TB (7.5% versus 7.3%, p = 0.433) and NTM-PD (4.0% versus 3.7%, p = 0.081). All extrapulmonary comorbidities were more frequent in the bronchiectasis patients with GORD than in those without GORD. The proportion of patients with CCI ⩾ 2 was also higher in bronchiectasis patients with GORD than in those without GORD (86.3% versus 68.6%, p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population.

| Total (N = 44,119) |

BE with GORD (n = 10,043) |

BE without GORD (n = 34,076) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean | <0.001 | |||

| 20–29 years | 728 (1.7) | 66 (0.7) | 662 (1.9) | |

| 30–39 years | 1715 (3.9) | 178 (1.8) | 1537 (4.5) | |

| 40–49 years | 4354 (9.9) | 638 (6.4) | 3716 (10.9) | |

| 50–59 years | 10,707 (24.3) | 2402 (23.9) | 8305 (24.4) | |

| 60–69 years | 12,810 (29.0) | 3350 (33.4) | 9460 (27.8) | |

| ⩾70 years | 13,805 (31.3) | 3409 (33.9) | 10,396 (30.5) | |

| Sex | 0.003 | |||

| Male | 19,766 (44.8) | 4371 (43.5) | 15,395 (45.2) | |

| Female | 24,353 (55.2) | 5672 (56.5) | 18,681 (54.8) | |

| Type of insurance | <0.001 | |||

| Self-employed health insurance | 40,484 (91.8) | 8936 (89.0) | 31,548 (92.6) | |

| Medical aid | 3406 (7.7) | 1030 (10.3) | 2376 (7.0) | |

| Others | 229 (0.5) | 77 (0.8) | 152 (0.5) | |

| Pulmonary comorbidities | ||||

| COPD | 16,600 (37.6) | 4432 (44.1) | 12,168 (35.7) | <0.001 |

| Asthma | 19,591 (44.4) | 5239 (52.2) | 14,352 (42.1) | <0.001 |

| Pulmonary TB | 3229 (7.3) | 753 (7.5) | 2476 (7.3) | 0.433 |

| NTM-PD | 1651 (3.7) | 405 (4.0) | 1246 (3.7) | 0.081 |

| Lung cancer | 1618 (3.7) | 450 (4.5) | 1168 (3.4) | <0.001 |

| Extrapulmonary comorbidities | ||||

| Cerebrovascular disease | 6137 (13.9) | 1846 (18.4) | 4291 (12.6) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 19,899 (45.1) | 5373 (53.5) | 14,526 (42.6) | <0.001 |

| Angina or MI | 6580 (14.9) | 2159 (21.5) | 4421 (13.0) | <0.001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 4002 (9.1) | 1269 (12.6) | 2733 (8.0) | <0.001 |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 160 (0.4) | 56 (0.6) | 104 (0.3) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 12,899 (29.2) | 3801 (37.9) | 9098 (26.7) | <0.001 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 979 (2.2) | 308 (3.1) | 671 (2.0) | <0.001 |

| Connective tissue disease | 3060 (6.9) | 1064 (10.6) | 1996 (5.9) | <0.001 |

| Charlson comorbidities index | <0.001 | |||

| 0 or 1 | 12,083 (27.4) | 1372 (13.7) | 10,711 (31.4) | |

| 2 or more | 32,036 (72.6) | 8671 (86.3) | 23,365 (68.6) |

BE, bronchiectasis; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GORD, gastro-oesophageal reflux; MI, myocardial infarction; NTM-PD, non-tuberculous mycobacteria pulmonary disease; TB, tuberculosis.

Data are presented as number (%) or mean (standard deviation).

Healthcare use and medical costs according to the presence or absence of bronchiectasis

As shown in Table 2, bronchiectasis patients with GORD showed increased healthcare use compared with those without GORD. The numbers of all-cause OPD visits (47.6 ± 38.6 versus 30.0 ± 28.6/person/year), respiratory disease-related OPD visits (8.6 ± 10.6 versus 6.8 ± 8.5 person/year), all-cause ER visits or hospitalizations (1.7 ± 3.3 versus 1.1 ± 2.8/person/year), and respiratory disease-related ER visits or hospitalizations (0.4 ± 1.4 versus 0.3 ± 0.9/person/year) were all increased (p < 0.001 for all).

Table 2.

Comparison of healthcare use and medical costs.

| Total (N = 44,119) |

BE with GORD (n = 10,043) |

BE without GORD (n = 34,076) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthcare use | ||||

| Number of all-cause OPD visits (/person/year) | 34.0 ± 32.0 | 47.6 ± 38.6 | 30.0 ± 28.6 | <0.001 |

| Number of respiratory disease-related OPD visits (/person/year) | 7.2 ± 9.0 | 8.6 ± 10.6 | 6.8 ± 8.5 | <0.001 |

| Number of all-cause ER visits or hospitalizations (/person/year) | 1.2 ± 3.0 | 1.7 ± 3.3 | 1.1 ± 2.8 | <0.001 |

| Number of respiratory disease-related ER visits or hospitalizations (/person/year) | 0.3 ± 1.1 | 0.4 ± 1.4 | 0.3 ± 0.9 | <0.001 |

| Medical costs | ||||

| Total medical costs (Euro a /person/year) | 2509.6 ± 5005.5 | 3564.5 ± 6372.6 | 2198.7 ± 4477.4 | <0.001 |

| Respiratory disease-related medical costs (Euro a /person/year) | 562.6 ± 2021.2 | 773.9 ± 2717.1 | 500.3 ± 1759.7 | <0.001 |

BE, bronchiectasis; ER, emergency room; GORD, gastro-oesophageal reflux; OPD, outpatient department.

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

One Euro = 1341.9 Won (27 April 2021).

In addition, total medical costs (3564.5 ± 6372.6 versus 2198.7 ± 4477.4 Euro/person/year, p < 0.001) and respiratory disease-related medical costs (773.9 ± 2717.1 versus 500.3 ± 1759.7 Euro/person/year, p < 0.001) were significantly higher in bronchiectasis patients with GORD than in those without GORD.

Association between GORD and increased healthcare use and medical costs

As shown in Table 3, both all-cause (adjusted odds ratio = 1.44, 95% confidence interval = 1.37–1.50) and respiratory disease-related (adjusted odds ratio = 1.26, 95% confidence interval = 1.19–1.33) healthcare use were significantly higher in bronchiectasis patients with GORD than in those without GORD.

Table 3.

Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals of GORD for healthcare use in patients with bronchiectasis.

| Model | Emergency room visits or hospitalizations | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| All-cause | Respiratory-related | ||

| Without GORD | Reference | Reference | |

| With GORD | Unadjusted | 1.69 (1.62–1.77) | 1.41 (1.34–1.49) |

| Adjusted | 1.44 (1.37–1.50) | 1.26 (1.19–1.33) | |

GORD, gastro-oesophageal reflux.

Adjusted values were adjusted for age, sex, type of insurance, and Charlson comorbidity index.

These differences persisted even after adjusting for potential confounders. The adjusted total medical costs (4337.3 ± 13,662.4 versus 3397.4 ± 24,001.4 Euro/person/year, p < 0.001) and adjusted respiratory disease-related medical costs (920.7 ± 5665.6 versus 720.2 ± 9953.0 Euro/person/year, p < 0.001) were significantly higher in bronchiectasis patients with GORD than in those without GORD (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of estimated medical costs after adjusting for potential confounders.

| Total (N = 44,119) |

BE with GORD (n = 10,043) |

BE without GORD (n = 34,076) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated total medical costs (Euro a /person/year) b | 3613.1 ± 27,264.8 | 4337.3 ± 13,662.4 | 3397.4 ± 24,001.4 | <0.001 |

| Estimated respiratory disease-related medical costs (Euro a /person/year) b | 766.2 ± 9913.1 | 920.7 ± 5665.6 | 720.2 ± 9953.0 | <0.001 |

BE, bronchiectasis; GORD, gastro-oesophageal reflux.

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

One Euro = 1341.9 Won (27 April 2021).

Adjusted for age, sex, type of insurance, and Charlson comorbidity index.

Discussion

In this study, using a large representative population-based database, we evaluated the prevalence of GORD and its impact on healthcare use and medical costs in patients with bronchiectasis. We found that the prevalence of GORD has increased over the 9-year study period, especially in the population aged 50 years or older. GORD in patients with bronchiectasis was substantially associated with increased OPD visits, ER visits or hospitalizations, and medical costs.

The prevalence of GORD in patients with bronchiectasis is highly variable depending on study methods but has been demonstrated to be up to 79% in patients with bronchiectasis. 12 Consistent with previous findings, our study found that a considerable number of patients with bronchiectasis (about 30% in our study) have GORD and, surprisingly, the prevalence of GORD has been increasing during the study period. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study showing the increasing prevalence of GORD, which indicates the importance of this comorbidity in patients with bronchiectasis.

Interestingly, while the prevalence of bronchiectasis in patients aged under 50 years was stable, there was a strikingly increased prevalence among the 50s and older population. The reasons are not clear as our study did not aim to evaluate this association. However, we suggest a few possible explanations for this finding. Previous studies showed that aging is a risk factor of GORD, and risk factors for GORD increase with age (e.g. delayed gastric emptying).20–22 In addition, aging is associated with increased symptoms of bronchiectasis such as coughing and sputum production. As coughing and sputum production naturally increase abdominal pressure, reflux symptoms may occur in patients with bronchiectasis. Although our study could not provide a detailed explanation or mechanism, our study results do suggest that the burden of GORD is increased in older age groups.

The most important finding of our study is that GORD is associated with increased healthcare use and medical costs in patients with bronchiectasis. All-cause and respiratory disease-related OPD visits and ER visits or hospitalizations were significantly higher in bronchiectasis patients with GORD, which might lead to an increase in medical expense. To some extent, the increased healthcare burden in this population can be attributable to the clinical characteristics of bronchiectasis patients with GORD, including older age, lower socioeconomic status, and higher number of comorbidities, compared to those without GORD. However, importantly, after adjusting these factors, the disease burden was still substantially higher in bronchiectasis patients with GORD compared with those without GORD, indicating that GORD is an important contributor to this phenomenon.

The reasons for the increased healthcare burden in bronchiectasis patients with GORD can be explained by the interactive bidirectional relationship between GORD and bronchiectasis, which leads to worsening conditions of both diseases. Patients with bronchiectasis often have hyperinflated lungs with the descent diaphragm that predisposes the patient to reflux by lowering the resting pressure of the lower oesophageal sphincter. 23 In addition, chronic respiratory symptoms, such as cough and sputum production, can lead to a recurrent sudden increase in intra-abdominal pressure, predisposing reflux. 23 Also, refluxate, whether acidic, nonacidic, or gaseous mistic, 24 can be proinflammatory and cause lung damage, aggravating the bronchiectasis. 23 This will cause a vicious cycle of worsened GORD and bronchiectasis. Our study results are meaningful in terms of providing evidence supporting the theoretical link between bronchiectasis and GORD in increasing healthcare costs.

Despite the close association between GORD and bronchiectasis, whether appropriate management of GORD may help improve treatment outcomes in patients with bronchiectasis remains unclear. A case series showed that anti-reflux surgery substantially improved bronchiectasis. 25 Regarding medical treatment, there have been no randomized controlled trials that demonstrate the effectiveness of proton pump inhibitor use in improving the treatment outcomes in bronchiectasis patients with GORD. While airway clearance technique in sitting position is recommended in bronchiectasis patients with GORD to minimize reflux, 26 the usefulness of this technique has not been demonstrated. Although the clinical efficacy of current treatment of GORD has not been demonstrated, clinicians should assess comorbid GORD in patients with bronchiectasis who are hampered by frequent exacerbations. 13 We also suggest that collaborative work between pulmonologists and gastroenterologists may be beneficial for the control of both diseases. Also, clinical studies are urgently needed to test whether controlling GORD can improve the treatment outcomes of bronchiectasis and vice versa.

The strength of this study is that our findings were obtained from a large national dataset, which represents the entire population. We used the largest number of bronchiectasis patients with GORD in our evaluation. However, there are some potential limitations. First, we used the ICD-10 code with medication to define both GORD and bronchiectasis since the HIRA-NPS database does not provide objective test results for diagnosing GORD (e.g. ambulatory pH monitoring) and bronchiectasis (e.g. computed tomography scan of the chest). Thus, both diseases might be over- or under-diagnosed. Second, GORD is generally considered to be more common in patients with severe bronchiectasis, 27 which could be a confounding factor for increased medical care costs or medical utilization in this study. However, as pulmonary function tests and computed tomography findings are not available in the HIRA-NPS database, we could not adjust for the severity of bronchiectasis. Future studies considering the severity of bronchiectasis are needed to address this issue. Third, our study was conducted in the Korean population; to generalize our study findings, studies from other countries are needed. Finally, a causal relationship between GORD and bronchiectasis has not been established due to the cross-sectional nature of the study. However, we achieved our study aim, and future studies using longitudinal databases are needed to confirm and expand upon our results.

Conclusion

In patients with bronchiectasis, the presence of GORD increases healthcare use and medical costs. Early recognition and appropriate management of this comorbidity should be helpful in reducing bronchiectasis disease burden.

Footnotes

Author contributions: HC and HL are guarantors of the manuscript. JHY, SHK, JR, HC, and HL designed the study; JR and CKY performed data analysis. JHY, SHK, HC, and HL wrote the initial draft of the manuscript, and all authors were involved at all stages of critical revision of the manuscript. All of the authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors meet the criteria for authorship as recommended by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Ministry of Science, Information and Communications Technologies (No. 2020R1F1A1070468 and 2021M3E5D1A0101517621 to H.L.; 2019R1G1A1008692 to H.C.) and the Korean Ministry of Education (No. 2021R1I1A3052416 to H.C.). The funders had no role in the design of the study, the collection and analysis of the data, or the preparation of the manuscript.

Ethical approval: The Institutional Review Board of the Hanyang University Hospital approved the study and waived the requirement for informed consent because the HIRA-NPS data were de-identified (application no. HYUH 2021-04-018).

Patient and public involvement: Patients or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of our research.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

ORCID iD: Hyun Lee  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1269-0913

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1269-0913

Data availability statement: Data of our study are available upon reasonable request.

Contributor Information

Jai Hoon Yoon, Department of Gastroenterology, Hanyang University Hospital, Seoul, Korea.

Sang Hyuk Kim, Division of Pulmonology and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Medicine, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

Jiin Ryu, Biostatistical Consulting and Research Lab, Medical Research Collaborating Center, Hanyang University, Seoul, Korea.

Sung Jun Chung, Division of Pulmonary Medicine and Allergy, Department of Internal Medicine, Hanyang University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

Youlim Kim, Division of Pulmonary, Allergy and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Konkuk University Hospital, School of Medicine, Konkuk University, Seoul, Korea.

Chang Ki Yoon, Department of Ophthalmology, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea.

Seung Won Ra, Division of Pulmonary Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Ulsan University Hospital, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Ulsan, Korea.

Yeon Mok Oh, Department of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea.

Hayoung Choi, Division of Pulmonary, Allergy, and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Hallym University Kangnam Sacred Heart Hospital, Hallym University College of Medicine, 1 Singil-ro, Yeongdeungpo-gu, Seoul 07441, Korea.

Hyun Lee, Division of Pulmonary Medicine and Allergy, Department of Internal Medicine, Hanyang University College of Medicine, 222-1, Wangsimni-ro, Seongdong-gu, Seoul 04763, Korea.

References

- 1. Aliberti S, Sotgiu G, Lapi F, et al. Prevalence and incidence of bronchiectasis in Italy. BMC Pulm Med 2020; 20: 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yang B, Choi H, Lim JH, et al. The disease burden of bronchiectasis in comparison with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a national database study in Korea. Ann Transl Med 2019; 7: 770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Quint JK, Millett ER, Joshi M, et al. Changes in the incidence, prevalence and mortality of bronchiectasis in the UK from 2004 to 2013: a population-based cohort study. Eur Respir J 2016; 47: 186–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Diel R, Chalmers JD, Rabe KF, et al. Economic burden of bronchiectasis in Germany. Eur Respir J 2019; 53: 1802033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Abo-Leyah H, Chalmers JD. Managing and preventing exacerbation of bronchiectasis. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2020; 33: 189–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Choi H, Yang B, Kim YJ, et al. Increased mortality in patients with non cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis with respiratory comorbidities. Sci Rep 2021; 11: 7126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chalmers JD, Aliberti S, Blasi F. Management of bronchiectasis in adults. Eur Respir J 2015; 45: 1446–1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yang B, Jang HJ, Chung SJ, et al. Factors associated with bronchiectasis in Korea: a national database study. Ann Transl Med 2020; 8: 1350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. McDonnell MJ, Aliberti S, Goeminne PC, et al. Comorbidities and the risk of mortality in patients with bronchiectasis: an international multicentre cohort study. Lancet Respir Med 2016; 4: 969–979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McDonnell MJ, Ahmed M, Das J, et al. Hiatal hernias are correlated with increased severity of non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis. Respirology 2015; 20: 749–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Choi H, Yang B, Nam H, et al. Population-based prevalence of bronchiectasis and associated comorbidities in South Korea. Eur Respir J 2019; 54: 1900194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. McDonnell MJ, O’Toole D, Ward C, et al. A qualitative synthesis of gastro-oesophageal reflux in bronchiectasis: current understanding and future risk. Respir Med 2018; 141: 132–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mcdonnell M, Rutherford R, De Soyza A, et al. The association between gastro-oesophageal reflux and exacerbations of bronchiectasis: data from the EMBARC registry. Eur Respir J 2017; 50: OA1968. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kim DS. Introduction: health of the health care system in Korea. Soc Work Public Health 2010; 25: 127–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Song S, Lee SE, Oh SK, et al. Demographics, treatment trends, and survival rate in incident pulmonary artery hypertension in Korea: a nationwide study based on the health insurance review and assessment service database. PLoS ONE 2018; 13: e0209148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kim L, Sakong J, Kim Y, et al. Developing the inpatient sample for the National Health Insurance claims data. Health Policy Manag 2013; 23: 152–161. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kim SY, Min C, Oh DJ, et al. Bidirectional association between GERD and asthma: two longitudinal follow-up studies using a national sample cohort. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2020; 8: 1005–1013.e1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kim JA, Yoon S, Kim LY, et al. Towards actualizing the value potential of Korea Health Insurance Review and Assessment (HIRA) data as a resource for health research: strengths, limitations, applications, and strategies for optimal use of HIRA data. J Korean Med Sci 2017; 32: 718–728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol 1992; 45: 613–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Richter JE, Rubenstein JH. Presentation and epidemiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology 2018; 154: 267–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pauwels A, Blondeau K, Mertens V, et al. Gastric emptying and different types of reflux in adult patients with cystic fibrosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011; 34: 799–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chang P, Friedenberg F. Obesity and GERD. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2014; 43: 161–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. McDonnell MJ, Hunt EB, Ward C, et al. Current therapies for gastro-oesophageal reflux in the setting of chronic lung disease: state of the art review. ERJ Open Res 2020; 6: 00190-2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sifrim D, Holloway R, Silny J, et al. Acid, nonacid, and gas reflux in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease during ambulatory 24-hour pH-impedance recordings. Gastroenterology 2001; 120: 1588–1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hu Z-W, Wang Z-G, Zhang Y, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux in bronchiectasis and the effect of anti-reflux treatment. BMC Pulm Med 2013; 13: 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hill AT, Sullivan AL, Chalmers JD, et al. British Thoracic Society guideline for bronchiectasis in adults. Thorax 2019; 74: 1–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McDonnell M, Michael O, David B, et al. Increased disease severity and mortality associated with the bronchiectasis-GORD phenotype. Eur Respir Soc 2015; 46: PA366. [Google Scholar]