Abstract

Objective:

To assess telehealth practice for headache visits in the US.

Background:

The rapid roll-out of telehealth during the covid-19 pandemic impacted headache specialists.

Methods:

American Headache Society (AHS) members were emailed an anonymous survey (9/9/20–10/12/20) to complete if they had logged ≥2 months or 50+ headache visits via telehealth.

Results:

225 of 1348 (16.7%) members responded. Most were female (59.8%; 113/189). Median age was 47 (IQR 37–57)(N=154). The majority were MD/DOs (83.7%;159/190) and NP/PAs (14.7%; 28/190), and most (65.1%; 123/189) were in academia. Years in practice were: 0–3: 28; 4–10: 58; 11–20: 42; 20+: 61. Median number of telehealth visits was 120 (IQR 77.5–250) in prior 3 months. Respondents were “comfortable/very comfortable” treating via telehealth a (a) new patient with a chief complaint of headache ( Median, IQR 4(3–5)); (b) follow-up for migraine (Median, IQR 5(5–5)); (c) follow-up for secondary headache (Median, IQR 4(3–4)). About half (51.1%; 97/190) offer urgent telehealth. Beyond being unable to perform procedures, top barriers were conducting parts of the neurologic exam (157/189), absence of vital signs (117/189), and socio-economic/technologic barriers (91/189). Top positive attributes were patient convenience (185/190), reducing patient travel stress (172/190), patient cost reduction (151/190), flexibility with personal matters (128/190), patient comfort at home (114/190), and patient medications nearby (103/190). Only 21.3% (33/155) of providers said telehealth visit length differed from in-person visits and 55.3% (105/190) believe the no-show rate improved. Providers were “interested”/”very interested” (Median, IQR 4(3–5))(N=188) in digitally prescribing headache apps (medial 4 IQR 3–5) and “interested”/”very interested” in remotely monitoring patient symptoms (median 4, IQR 3–5).

Conclusions:

Respondents were comfortable treating migraine patients via telehealth. They note positive attributes for patients and how access may be improved. Technology innovations (remote vital signs, digitally prescribing headache apps) and remote symptom monitoring are areas of interest and warrant future research.

Keywords: telemedicine, teleheadache, clinical informatics, digital prescribing, remote monitoring, neurologic examination

INTRODUCTION

In 2012, a study of telemedicine practice in top US neurology departments found that 60% of departments provided telemedicine and that the majority had implemented telemedicine within the last two years.1 Initial work focused on provider-to-provider consultations in telestroke, telemovement and teleneurocritical care.1 More recently, studies of teleheadache have emerged, sharing themes such as perceived patient convenience,2–4 patient satisfaction,2,3,5–7 comparable clinical outcomes to in-person visits,3–5,7–9) shorter visit duration,3,4 and sufficiency of technology.4,8 Notably, studies mostly examined follow-up visits or visits that otherwise did not require full neurological exams at the time of telehealth for headache visits. Though expanding, telehealth, particularly from the patient’s home, represented the minority of headache visits at the time.

In March 2020, the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic prompted a rapid and widespread shift to telehealth for headache care. Regulations that previously limited reimbursement, coverage and technology for telehealth were loosened.10,11 Concerns continue to exist involving technology use and integration, conducting the neurologic exam, trainee education, workflow and office functions including billing, prior authorizations and prescribing.10,11

Given the recent emergence of telehealth, the lack of provider perspective, and the rapid shift to this practice under the circumstances, insight into the experience of headache providers can identify practice strengths and areas needing improvement in order to inform care both during and after the Covid-19 pandemic. We sought to examine headache specialist comfort level with treating a variety of cases, along with perceived barriers and benefits of telehealth, among other parameters.

METHODS

The Clinical Informatics and Primary Front Line Headache Care Special Interest Sections and other interested members of the American Headache Society (AHS) developed the tele-headache survey using an iterative approach. Between 9/9/2020 and 10/12/2020, we distributed an anonymous closed survey to all AHS members (1,348 members) via the SurveyMonkey program. No incentives were offered for voluntary completion of the survey. This research was conducted with approval through the Wake Forest Baptist Health Institutional Review Board with a waiver of consent/assent.

After the email with the initial invitation to complete the survey was distributed, two reminder emails were sent. In addition, individualized email reminders to capture members of the Primary Front Line Headache Care Special Interest Section were sent. Social media (e.g. Twitter) was utilized to remind AHS members to access the survey through their email. The survey can be found in the Appendix. This was a cross-sectional study.

Respondents were asked to complete the survey if they had experience conducting headache visits via telemedicine for greater than 2 months or if they had conducted 50 or more headache visits via telemedicine. With adaptive questioning, if a participant answered yes, they were asked further questions about their practice habits related to telehealth. If they answered no, the survey was considered completed.

The online survey consisted of two screens. To minimize the number of separate questions and viewable survey screens, questions on similar themes were placed in a table format. There was a varied number of questions/screen. There were questions on the respondent’s characteristics, logistics of telehealth visits, and provider responses on various topics. Data from all questions were reported in tables within this paper. The survey did not have a completeness check in place that required answers before advancing screens within the survey. While participants were within the survey, they could edit responses to prior questions, but they could not return to the survey once complete.

No additional techniques were used to identify duplicate responses via log file analysis or elimination or review of duplicate user IP addresses. The length of time used to fill out the questionnaire was not monitored. The SurveyMonkey policy on cookies can be viewed at https://www.surveymonkey.com/mp/legal/cookies/. There are required cookies that are necessary to for the website to maintain security.

Statistical Analyses

Primary analysis of this survey data was conducted. Descriptive analyses including frequency, percentages, medians, and interquartile ranges (IQRs) were conducted using Excel version 16.41 and STATA 16. All survey responses (including incomplete) were included in data analysis. Responses regarding comfort level and level of concern were converted to Likert scores as defined in the survey. Qualitative responses were included as either comments offering details to selected responses, as selections of offered options, or as “other” responses and categorized. In select circumstances representative quotes were selected.

RESULTS

A total of 225 (16.7%) AHS members had completed at least 2 months or at least 50 telehealth headache visits and responded to the survey. The response rate was 225/1348 (16.7%). 81% of these respondents (182/225) completed all the practice evaluation questions. (There were 35 respondents who did not complete the survey beyond answering “Yes” to having completed a minimum of two months or 50 headache visits via telehealth.) Characteristics of respondents can be found in Table 1. The majority of providers were MD/DOs (159/190, 83.7%), female (113/189, 59.8%) and most were in academic practice (123/189, 65.1%). Years in practice were varied and widely distributed.

Table 1:

Headache provider characteristics

| Title | N = 190 | |

| MD/DO | 159 | 83.7% |

| NP/PA | 28 | 14.7% |

| PhD | 2 | 1.1% |

| Othera | 1 | 0.5% |

| Type of practice | N = 189 | |

| Academic | 123 | 65.1% |

| Private | 66 | 34.9% |

| Gender | N = 189 | |

| Female | 113 | 59.8% |

| Male | 76 | 40.2% |

| Age (years) | N = 154 | |

| Median, IQRb | Range | |

| 47 (37–57) | 29–75 | |

| Years in practice | N = 189 | |

| 0–3 | 28 | 14.8% |

| 4–10 | 58 | 30.7% |

| 11–20 | 42 | 22.2% |

| 20+ | 61 | 32.3% |

| Number of headache visits in previous 3 months | N = 180 | |

| Median, IQR | Range | |

| 120 (77.5–250) | 30–2000 | |

Professor,

IQR = Interquartile Range

Logistics of telehealth headache visits are listed in Table 2. Over half (97/190, 51.1%) of respondents offered urgent/emergent telehealth visits, and most (148/189, 78.3%) offered visits to address patient concerns after receiving telephone or other forms of communication from patients. Nearly half (73/155, 47.1%) of providers who responded had dedicated telehealth sessions. The vast majority (122/155, 78.7%) saw patients for the same amount of time for telehealth and/or with the same intervals between visits compared to in-person headache visits. The majority of respondents perceived improved (105/190, 55.3%) or unchanged (63/190, 33.2%) no show rates with telehealth visits.

Table 2:

Logistics of teleheadache

| Offer urgent/emergent teleheadache visits | N = 190 | 97 | 51.1% |

| Advise making a teleheadache visit after receiving patient messages | N = 189 | 148 | 78.3% |

| Scheduling of teleheadache versus face-to-face visits (multiple selections allowed) a | N = 155 | ||

| Pure tele-headache session(s) (provider does not see in-person visits during the 1/2 or 1 day clinic session, only telehealth patients) | 73 | 47.1% | |

| Teleheadache integrated with in-person/had same scheduling | 42 | 27.1% | |

| Different visit length and/or interval | 33 | 21.3% | |

| Different time of day or week (e.g. evening or weekends) | 25 | 16.1% | |

| Other | 5 | 3.2% | |

| Effect of teleheadache on no-show rate b | N = 190 | ||

| It has improved | 105 | 55.3% | |

| It is the same | 63 | 33.2% | |

| It has worsened | 8 | 4.2% | |

| Uncertain | 14 | 7.4% | |

Comments include: difficulty integrating telehealth and in-person visits (1), longer visits (2), must space teleheadache visits further apart because cannot run late (1), faster pace seeing patients, in-person visits spaced out to 1 per hr for covid safety (1), seems to help with timing, some teleheadache visits as short as 15 min, some >1 hour - it evens out (1).

Comments include: provider calls patients if no show (3), sicker patients more likely to show up for telehealth visit than in-office visit (1), improved patient convenience (1), patient comfort during covid (1) some no shows due to technological issues (4), patients forget about/not ready for visit (2), varies by patient as some pick up providers call regardless of location, some have technological issues, some forget, difficult transition to teleheadache by scheduling center (1)

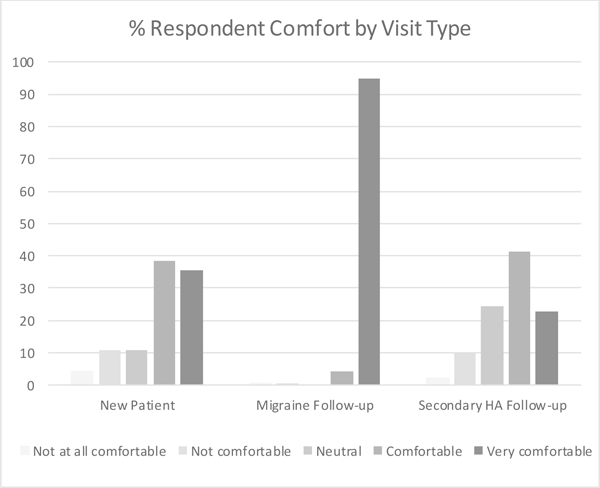

Provider concerns and interests related to telehealth headache visits are found in Table 3. Based on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = “not at all comfortable/interested”, 5 = “very comfortable/interested”), providers who completed the online survey were comfortable using telehealth to treat a new patient with a chief complaint of headache (Median 4, Interquartile range (IQR) 3–5). See figure 1 for distribution of responses. They were very comfortable using telehealth to treat patients in follow-up for migraine (assuming an in-person procedure was not indicated) (median 5, IQR 5–5). Representative quotes regarding provider comfort include: “If I feel comfortable with the diagnosis of migraine, these visits are easy to do via video as most of the visit is medication review/adjustment,” “If stable and not needing to be seen, works well,” “I do a very complete web-cam based neuro exam,” “The history is paramount. You can do an exam by video as well,” “In those patients who I’ve examined I am comfortable not examining them at return visits,” “Again, I do it and I feel I offer excellent care and I have mastered the technology, but it makes me uncomfortable to not be able to do the full in-person evaluation.” Providers were comfortable using telehealth to evaluate a patient with a secondary headache at a follow-up visit (median 4, IQR 3–4). Provider comments related to comfort level were categorized as follows: depends on type of secondary headache (13), would prefer option to do better exam particularly ophthalmologic (10), depends on if red flags (5), depends on if work up already completed (4), can use history and do exam by video (1), depends on if chronic/non-acute setting (1).

Table 3:

Provider responses

| Comfort level in treating (1–5, 1 = not at all comfortable, 5 = very comfortable): | N | Median, IQR |

| A new patient with a chief complaint of headache via tele-headache | 185 | 4 (3–5) |

| A patient in follow-up for migraine via teleheadache (assuming an in-person procedure is not indicated) | 186 | 5 (5–5) |

| A patient with a secondary headache for a follow-up via tele-headache | 182 | 4 (3–4) |

| Interest in (1–5, 1=not at all interested, 5 = very interested) | N | Median, IQR |

| Digitally prescribing headache apps | 188 | 4 (3–5) |

| Remote monitoring of patient symptoms if the information is directly inputted from a digitally prescribed app into the EMR system | 189 | 4 (3–5) |

| Concern about (1–5, 1= very concerned, 5 = not at all concerned) | N | Median, IQR |

| Patient privacy and confidentiality | 189 | 3 (2–4) |

| Obtaining informed consent | 189 | 3 (2–4) |

| Inadequate chart preparation (i.e. no or inadequate medical assistant or nurse previsit charting) | 187 | 3 (2–4) |

| Inadequate check-out procedures | 188 | 3 (2–4) |

| Lack of uniform reimbursement policies | 188 | 2 (1–3) |

| Poor reimbursement | 189 | 2(1–3) |

| Insurance rescinding reimbursement | 188 | 2 (1–3) |

| Other (please specify) | 16 |

Figure 1:

Respondent comfort based on visit type

Providers who completed the online survey were interested in digitally prescribing headache applications (apps) (median 4, IQR 3–5). Comments were categorized as: no consensus on which apps are best to recommend (3), increased accessibility (1), lack of integration with the Electronic Medical Record (EMR) and ease of use in reviewing app data (4), increased adherence (1), preferred evidence-based treatments (3), allows focus on specific issues (1). Regarding the remote monitoring of patient symptoms if the information is directly inputted from a digitally prescribed application into the EMR system (median 4, IQR 3–5), comments were categorized as: lack of time (5), poor quality of data (5), review data at visits only (2), allows for individualized follow up timing (1), same compliance issues as with other diaries (1), and need for ancillary support to manage data (1).

Based on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = very concerned, 5 = very not at all concerned), providers who responded were neutral about patient privacy and confidentiality, obtaining informed consent, inadequate chart preparation (no, or inadequate, medical assistant or nurse pre-visit charting), and inadequate check-out procedures (median 3, IQR 2–4 for each). Providers were most concerned with lack of uniform reimbursement policies, poor reimbursement, and insurance rescinding reimbursement (median 2, IQR 1–3 for each).

As shown in Table 4, the top five situations regarded as poor matches for telehealth by headache providers included neurologic emergencies such as patients with “red flags” (163/187), patients who may have difficulty using and/or accessing technology (145/187), patients who need the assistance of interpreter services (104/187), new patients (7 4/187), and follow-ups with a new medical complaint (55/187). Positive attributes of telehealth recognized by headache providers can be found in Table 5. The top 6 positive attributes of telehealth headache visits were patient convenience (such as no parking or traffic) (185/190), reducing stress of travel for patient (172/190), saving money on travel for patient (151/190), flexibil ity (childcare, eldercare, managing other personal matters) (128/190), patients feeling more comfortable in their own home (114/190), and patients having medications nearby for review if needed (103/190). As shown in Table 6, top barriers include performing parts of the neurologic exam (157/189), not obtaining vital signs (117/189), no access for patient to telehealth due to socioeconomic and/or technologic issues (91/189), and the patient not being prepared for the visit (79/189).

Table 4:

Situations believed to be poor matches for tele-headache

| Situation (multiple selections allowed) | N = 187 | |

| Neurologic emergencies such as patients with “red flags” (stroke and so on) | 163 | 87.2% |

| Patients who may have difficulty using/accessing the technologya | 145 | 77.5% |

| Patients who need the assistance of interpreter services | 104 | 55.6% |

| New patients | 74 | 39.6% |

| Follow ups with new medical complaint | 55 | 29.4% |

| Any patients who live close by | 5 | 2.7% |

| Any appointments for headache medicine | 5 | 2.7% |

| Other | 10 | 5.3% |

Patients who are hard of hearing (2)

Depends on what can be assessed by video (1); conditions: status migranosis (1), intracranial hypertension (1), cervicogenic headache, tmd, abnormal neurologic exam (1), secondary headache and far from ED (1); can bring in for exam later if needed (2); complex patients (2); comorbidities related to covid susceptibility (1); all can be done by teleheadache (1);

Table 5:

Positive attributes of teleheadache

| Positive attributes of teleheadache (choose top 5) | N = 190 | |

| Convenience (such as no parking, no traffic) for the patient | 185 | 97.4% |

| No stress of travel for the patient | 172 | 90.5% |

| Saving money on travel for the patient | 151 | 79.5% |

| Flexibility (childcare, eldercare, managing other personal matters) | 128 | 67.4% |

| Patients feel more comfortable at their own home | 114 | 60.0% |

| Patients have all medications there for review, if needed | 103 | 54.2% |

| No triggers such as bright lights, smells of clinic offices | 96 | 50.5% |

| Convenience (such as no parking, no traffic) for the provider | 83 | 43.7% |

| Providers can work/see patients from home | 77 | 40.5% |

| Ability to assess the patient’s home environment | 74 | 38.9% |

| No stress of travel for the provider | 35 | 18.4% |

| Saving money on travel for the provider | 34 | 17.9% |

| Othera | 22 | 11.6% |

Comments grouped into the following categories: safer during covid (6), increased efficiency (4), provider does teleheadache from office so no added convenience (3), increased geographic reach of patients (2), flexibility for patient (1), flexibility for provider in scheduling (1), less stress for patient or provider during wait times (2), financial savings for provider (1), more frequent check-ins with patients who need it (1), teleheadache is not ideal and not an equal substitute for most patient visits other than routine refills (1).

Table 6:

Barriers to teleheadache

| Barriers other than the inability to perform procedures (multiple selections allowed) | N = 189 | |

| Parts of neurologic exama | 157 | 83.1% |

| Not getting vital signs | 117 | 61.9% |

| No access for patient to telehealth due to socio-economic, technologic issuesb | 91 | 48.1% |

| Patient not ready/prepared for visit | 79 | 41.8% |

| Distractions in the patient’s environment | 65 | 34.4% |

| Patient intake forms and screens are not integrated into the telemed system | 56 | 29.6% |

| Not being able to provide patient instructions/patient education materials in print | 52 | 27.5% |

| Difficulty reviewing printed headache logs | 44 | 23.3% |

| Difficulties in building therapeutic relationships | 40 | 21.2% |

| Family member/guardian/caretaker shows up for the visit without the patient | 36 | 19.0% |

| Unable to get labs, EKG, etc. same day testing which is typically done in the office | 34 | 18.0% |

| Difficulties arranging out of network orders/scripts (e.g. radiology or lab scripts) which could previously be printed on paper and handed to the patient | 23 | 12.2% |

| All of the neurologic exam | 22 | 11.6% |

| Sending miscellaneous/device (non drug) scripts | 18 | 9.5% |

| Provider difficulty completing patient forms (e.g. FMLA forms) | 16 | 8.5% |

| Distractions in the provider’s environment | 7 | 3.7% |

| Otherc | 33 | 17.5% |

not being able to do fundus exam is largest drawback

comments included lack of equipment for imaging disc sharing and review, lack of camera and microphone on patient computer, patients do not answer calls from blocked numbers, patient difficulty navigating EMR

”Other” responses categorized as follows: technology issues on either patient or provider end (8) with comments about poor video and/or sound quality (2), provider tech issues (1), teaching (1), unable to give patient instructions (3), unable to give medication samples (4), insurance concerns (1), initiating screening for psychiatric comorbidities (1), unable to give savings/access cards (1), unable to start mabs (1), lack of assistance from staffing, specifically medication reconciliation (3), procedures in place for pediatric patients regarding parent consent (1), not able to share educational materials because patient smartphone screen too small (1), difficult to conduct multidisciplinary clinic appts (1), difficult to coordinate visits with both patient and parent (1), concern about revenue regarding facility fees (1), scheduling issues between telehealth and in person (1), lack of time between patients (1), absolute cut-off times (1), lack of follow-ups scheduled because no check out desk (1)

DISCUSSION

The technological capability for direct-to-patient telehealth has been available for over a decade, but the public health crisis of COVID-19 forced abrupt changes to licensing laws and reimbursement which enabled widespread implementation almost overnight. In this survey of AHS members who focus on headache care in their practice, common themes emerged after several months of telehealth headache visits. First, many headache providers felt comfortable using telehealth, especially for follow-up visits, urgent visits to address patient issues, and visits where the clinicians had low suspicion of serious cause for headache. Conversely, many providers reported concerns about the inability to complete certain parts of the neurological examination with new patients, evaluate new symptoms/problems, and develop rapport with patients. Providers reported concerns with some of the operations of telehealth clinics, difficulties integrating other members of the care team efficiently in this visit format, and concerns with the current and future state of insurance coverage and reimbursement rates.

Many providers who completed the online survey were comfortable treating patients with headaches via telemedicine, which is consistent with research demonstrating provider acceptance across neurology,12,13 and with prior research demonstrating the benefits of tele-headache visits. A non-inferiority prospective open label RCT (N=402) was conducted to assess the long-term treatment outcomes of safety of telemedicine consults for nonacute headaches in a secondary neurologic outpatient department.9 Patients were screened prior to enrollment to best ensure that the patients were presenting with primary headaches. The study participants were randomly assigned to either see the provider in person in the outpatient exam room or to see the provider via tele-conference in an outpatient exam room. The primary outcomes were efficacy as measured by the Headache Impact Test 6 and safety as determined by the numbers of secondary headaches revealed within 12 months after the initial visit. Researchers found no difference between the telehealth and traditional consultations regarding change in headache disability or missing a secondary headache. They surveyed the same participants and found that satisfaction was similar between the two groups.5 In addition, they performed post-hoc analyses which found no differences in satisfaction across gender, patients with migraine, or rural versus urban patients. Participants reported equal improvement between baseline and three months. There were no differences in treatment compliance. The rural telehealth patients had less frequent headache visits at the three months follow-up. The authors concluded that telemedicine is non-inferior to traditional in-person consultations regarding patient satisfaction, specialist evaluation, and treatment of non-acute headaches. Another open label prospective one-year RCT assessed tele-headache follow-up visits and found that of 96 scheduled visits, 89 were successfully conducted using telemedicine.3 Clinical outcomes including migraine disability, number of headache days, and headache severity were the same between groups. Convenience was rated higher and visit lengths were decreased in the telemedicine group. There were fewer drops outs in the telemedicine groups (4/22) compared to the in -office group (11/23). Recently, a quality improvement telephone-based survey of patients in Hawaii who participated in telehealth at the beginning of the Covid −19 pandemic revealed that telehealth was well received by almost all patients who participated in it, and most of those patients found telehealth to be easy to use and just as valuable as an in‐person visit.14 Those with migraine reported with a greater frequency that without the telehealth option, they would have missed their medical appointments. Further, a majority reported that they would prefer or consider telehealth appointments in the future over in‐person visits.

Some providers were concerned about the sufficiency of the limited neurologic exam and their ability to develop rapport via telemedicine. Neurologists have written about ways to conduct a detailed exam and optimize a tele-neurology visit. 10,15 Headache specialists created a “Headache Virtual Visit Toolbox: The Transition From Bedside Manners to Webside Manners” to discuss how to best develop the rapport and optimize the patient experience. 16.

Teleheadache has the opportunity to continue care and possib ly expand access. The Global Burden of Disease study found that tension type headache and migraine are respectively the second and third most prevalent disorders in the world.17 There is a relative shortage of headache specialists to support this need to serve the country. Even in the Northeastern Region where there is the highest concentration of headache specialists, 123 headache specialists were practicing for an expected population of over 5.5 million affected by migraine, for an overwhelming patient-specialist ratio of 45,343:1.18 An important highlight of our survey results is that headache providers surveyed reported perceived improvement in no show rates of their telemedicine clinic visits compared to in-person clinics (105/190, 55.3%). This could indirectly improve much-needed access to headache specialty care if available appointments are filled at a higher rate.

Simultaneously providers who completed the online survey also have concerns about patients having technologic issues and patients without access to telehealth due to poor socioeconomic status or the need for interpreter services. Telehealth headache visits may offer improved access, but there will need to be careful thought to whether this would create emerging disparities with access to video visits over telephone visits. In a study of 2,178,440 patient-scheduled primary care visits scheduled by 1,131,722 patients, 86% were scheduled as office visits and 14% as telemedicine visits, with 7% of the telemedicine visits by video. Choosin g telemedicine was significantly associated with age (patients ≥65 years were less likely than patients aged 18 to 44 years to choose telemedicine) as well as with technology access (patients in neighborhoods with high rates of residential internet access were more likely to choose a video visit than patients whose neighborhoods had limited internet access). 19 Disparities were also found in a telehealth study of neurology patients where older, male and black patients with Medicare or Medicaid insurance were less likely to adopt video visits over phone visits.20 Similarly in pediatric neurology patients, access to wifi, ability to use cell phones for video, and lower activation of the patient portal contributed to a significant reduction in scheduled appointments by patients of under-represented minority groups in the early months of the pandemic.21 Our surveyed headache providers appeared to view video visits as superior to telephone visits so that they could at least complete some aspects of the neurologic exam. They identified obtaining a neurologic exam as important particularly in visits with “red flags” where providers reported having a lower level of comfort.

Providers who completed the online survey were interested in digitally prescribing headache apps, and qualitative data indicated that they wanted to ensure data review and integration would be done in a way that would not be burdensome to them. This is likely to be an increasing topic of interest as telehealth continues to develop. Prior studies revealed that while headache diaries are the most commonly investigated area of study, other headache digital health tools have been investigated. For example, in a scoping review of digital health tools, 27/39 studies focused on headache diaries; digitally based cognitive behavioral therapy was common (7/39). Other digital health tool categories were teleconsultation (4/39), telemonitoring (medication adherence) (2/39) and patient portal (2/39).22 In addition, one study examined a headache training tool for specialists. The telemonitoring is important for patients too. Many people with migraine are using smartphone apps. One 2018 study found the top 15 migraine apps on the market in the Google Play and in the Apple Stores had an average of 72,440 ±256,628 (100–1,000,000) downloads.23 Research has demonstrated that patients with migraine are willing to track their symptoms and are interested in sharing their electronic headache diary data with their providers.24,25 Thus, going forward, studies may examine how providers can best digitally prescribe apps and, in turn, how they can efficiently review the patient-inputted data.

There were several strengths of this study. Providers had varied clinical degrees, both academic and private practice experiences, and a wide range of years of clinical experience. The survey asked detailed questions about the structure, strengths, and drawbacks of telehealth. In addition, the format of the survey enabled collection of both discrete data and substantial qualitative comments, which enriched the depth of information collected.

The main limitation of this study is the low response rate, at 16.7%. This response rate is slightly higher than the industry expectation from medical societies (AAPM Education Manager, email communication, July 15, 2020 “It’s our current understanding that industry standard quality response rate for surveys is 10%”). However, given the near universal use of telehealth for routine outpatient care in the United States in Spring 2020, we had expected a higher response rate. There may be several contributing factors: We requested responses from those members who had conducted telehealth headache visits for two months or who had completed at least 50 telehealth headache visits and sent the survey in September – October 2020. By that time many institutions and practices may have shifted back to higher percentage of in-person care, so many recipients of the survey may have felt that they did not meet the criteria for response. Like the population more generally, recipients may have “COVID fatigue,” meaning that people are tired of thinking about (and answering questions about) anything related to COVID 19, including COVID19-related changes in practice. Further, people may be even busier than usual – with many clinicians also serving as teachers and caretakers for family members, and they may have insufficient time to answer surveys.26 Another limitation is that the survey was not validated or tested for reliability due to the novelty of the topic. Thus, the providers’ interpretation of questions may not have been uniform e.g. providers might have different definitions of an urgent/emergent teleheadache visit. Additionally, the criteria for survey completion (2 months or 50 telehealth visits) may have resulted in selection bias because AHS members who did not favor telehealth or whose institutions/practices did not establish telehealth practices may not have qualified. Thus, those who completed the survey may have favored telehealth more or had more robust resources than those who did not. Moreover, those who do not feel comfortable with telehealth may also not complete an online survey because they may feel less technologically savvy. Another notable limitation is that this study only sought to evaluate the provider experience and did not study the patient experience with telehealth for headache visits. Finally, there was missing data and one reason for attrition may have been the length of the survey.

Future Work

The results of this study taken into context with the prior tele-headache studies show that tele-headache is likely beneficial for the headache patient population. However, there are many questions that remain unanswered - What will patient and provider preferences be after the pandemic? How can we use telehealth to reach headache patients who face geographic or socioeconomic barriers to care?

CONCLUSION

Expansion of telehealth visits for headache care has brought about a change to care delivery. There is a possibility that patients in the future may choose telehealth to avoid bright office lights and other possible triggers of headache which could be experienced during “in person clinic”. Headache providers are comfortable using telehealth, especially for follow-up visits, urgent visits to address patient issues, and visits where the clinicians had low suspicion of serious underlying causes. Further protocols, e.g., to improve acquisition of vital sign and examination data, will likely follow and attempts to back slide on insurance reimbursement and legal restrictions may occur. However, telehealth seems unlikely to disappear as telehealth has the opportunity to increase access for patients, and future directions can aim to improve the provider experience through improvement in technology, clinic operations, and electronic health integration with digital applications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

The authors would like to thank Dr. Nate Bennett for this review and suggestions regarding the study’s survey.

Funding

Dr. Minen receives funding the NIH NCCIH (K23 AT009706‐01)

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

Dr. Minen serves as the Chair of the AHS Special Interest Section Primary Front Line Headache Care which co-sponsored the survey. Christina L. Szperka has consulted personally or through her institution for Teva Pharmaceuticals, Lundbeck Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly and Company, and Upsher-Smith Laboratories. She serves as a site PI for studies for Amgen, Eli Lilly and Company, Teva Pharmaceuticals, and Theranica Bio-Electronics. She receives research funding from the NIH (K23NS102521), and has received funding from the FDA (1U18FD006298). Dr. Szperka serves on the AHS Practice Management Committee, and is the former Chair of the Clinical Informatics Special Interest Section of the AHS which co-sponsored the survey. Ms. Kaplan received funding from Barnard College to support her time working on this project. Ms. Ehrlich serves on Speaker Bureau for Lilly and Abbvie. She has served on advisory boards for Impel Neuropharma and Currax. Dr. Riggins served as PI on Gammacore RCT, consulted for Gerson Lehrman Group. Dr. Rizzoli served as Chair of the Clinical Informatics Special Interest Section at the time of survey distribution. Dr. Strauss reports no disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.George BP, Scoglio NJ, Reminick JI, et al. Telemedicine in leading US neurology departments. Neurohospitalist 2012;2(4):123–128. doi: 10.1177/1941874412450716 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Qubty W, Patniyot I, Gelfand A. Telemedicine in a pediatric headache clinic: A prospective survey. Neurology 2018;90(19):e1702–e1705. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000005482 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friedman DI, Rajan B, Seidmann A. A randomized trial of telemedicine for migraine management. Cephalalgia 2019;39(12):1577–1585. doi: 10.1177/0333102419868250 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muller KI, Alstadhaug KB, Bekkelund SI. Acceptability, feasibility, and cost of telemedicine for nonacute headaches: A randomized study comparing video and traditional consultations. J Med Internet Res 2016;18(5):e140. doi: 10.2196/jmir.5221 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muller KI, Alstadhaug KB, Bekkelund SI. Telemedicine in the management of non-acute headaches: A prospective, open-labelled non-inferiority, randomised clinical trial. Cephalalgia 2017;37(9):855–863. doi: 10.1177/0333102416654885 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muller KI, Alstadhaug KB, Bekkelund SI. Headache patients’ satisfaction with telemedicine: A 12-month follow-up randomized non-inferiority trial. Eur J Neurol 2017;24(6):807–815. doi: 10.1111/ene.13294 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vierhile A, Tuttle J, Adams H, tenHoopen C, Baylor E. Feasibility of providing pediatric neurology telemedicine care to youth with headache. J Pediatr Health Care 2018;32(5):500–506. doi: S0891–5245(17)30577–1 [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akiyama H, Hasegawa Y. A trial case of medical treatment for primary headache using telemedicine. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97(9):e9891. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000009891 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muller KI, Alstadhaug KB, Bekkelund SI. A randomized trial of telemedicine efficacy and safety for nonacute headaches. Neurology 2017;89(2):153–162. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004085 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grossman SN, Han SC, Balcer LJ, et al. Rapid implementation of virtual neurology in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Neurology 2020;94(24):1077–1087. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009677 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klein BC, Busis NA. COVID-19 is catalyzing the adoption of teleneurology. Neurology 2020;94(21):903–904. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009494 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rametta SC, Fridinger SE, Gonzalez AK, et al. Analyzing 2,589 child neurology telehealth encounters necessitated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Neurology 2020;95(9):e1257–e1266. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000010010 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Albert DVF, Das RR, Acharya JN, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on epilepsy care: A survey of the american epilepsy society membership. Epilepsy Curr 2020;20(5):316–324. doi: 10.1177/1535759720956994 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith M, Nakamoto M, Crocker J, et al. Early impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on outpatient migraine care in hawaii: Results of a quality improvement survey. Headache 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al Hussona M, Maher M, Chan D, et al. The virtual neurologic exam: Instructional videos and guidance for the COVID-19 era. Can J Neurol Sci 2020;47(5):598–603. doi: 10.1017/cjn.2020.96 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Begasse de Dhaem O, Bernstein C. Headache virtual visit toolbox: The transition from bedside manners to webside manners. Headache 2020;60(8):1743–1746. doi: 10.1111/head.13885 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet 2012;380(9859):2163–2196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mauser ED, Rosen NL. So many migraines, so few subspecialists: Analysis of the geographic location of united council for neurologic subspecialties (UCNS) certified headache subspecialists compared to united states headache demographics. Headache 2014;54(8):1347–1357. doi: 10.1111/head.12406 [doi]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reed ME, Huang J, Graetz I, et al. Patient characteristics associated with choosing a telemedicine visit vs office visit with the same primary care clinicians. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3(6):e205873. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.5873 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thurman AM, Olszewski C, Smith LD, et al. Rapid implementation of outpatient teleneurology in rural appalachia: Barriers and disparities. Neurol Clin Pract 2020;10(1212). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chadehumbe M, Craig S, Stephenson D, Helbig I. Child nEurology telemedicine – understanding the data we have and finding the patients we do not see. Pediatr Neurol 2021;116(84). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van de Graaf DL, Schoonman GG, Habibovic M, Pauws SC. Towards eHealth to support the health journey of headache patients: A scoping review. J Neurol 2020. doi: 10.1007/s00415-020-09981-3 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Minen MT, Gopal A, Sahyoun G, Stieglitz E, Torous J. The functionality, evidence, and privacy issues around smartphone apps for the top neuropsychiatric conditions. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2020:appineuropsych19120353. doi: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.19120353 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Minen MT, Gumpel T, Ali S, Sow F, Toy K. What are headache smartphone application (app) users actually looking for in apps: A qualitative analysis of app reviews to determine a patient centered approach to headache smartphone apps. Headache 2020;60(7):1392–1401. doi: 10.1111/head.13859 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Minen M, Jaran J, Boyers T, Corner S. Understanding what people with migraine consider to be important features of migraine tracking: An analysis of the utilization of Smartphone ‐Based migraine tracking with a Free‐Text feature. Headache 2020;60(7):1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krukowski RA, Jagsi R, Cardel MI. Academic productivity differences by gender and child age in science, technology, engineering, mathematics, and medicine faculty during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2020. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2020.8710 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.