Abstract

Background

Miscarriage is pregnancy loss before 23 weeks of gestational age. It happens in 10% to 15% of pregnancies depending on maternal age and parity. It is associated with chromosomal defects in about a half or two‐thirds of cases. Many interventions have been used to prevent miscarriage but bed rest is probably the most commonly prescribed especially in cases of threatened miscarriage and history of previous miscarriage. Since the etiology of miscarriage in most of the cases is not related to an excess of activity, it is unlikely that bed rest could be an effective strategy to reduce spontaneous miscarriage.

Objectives

To evaluate the effect of prescription of bed rest during pregnancy to prevent miscarriage in women at high risk of miscarriage.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (March 2010).

Selection criteria

We included all published, unpublished and ongoing randomized trials with reported data which compare clinical outcomes in pregnant women who were prescribed bed rest in hospital or at home for preventing miscarriage compared with alternative care or no intervention.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently assessed the methodological quality of included trials using the methods described in the Cochrane Reviewers' Handbook. Studies were included irrespective of their methodological quality.

Main results

Only two studies including 84 women were identified. There was no statistically significant difference in the risk of miscarriage in the bed rest group versus the no bed rest group (placebo or other treatment) (risk ratio (RR) 1.54, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.92 to 2.58). Neither bed rest in hospital nor bed rest at home showed a significant difference in the prevention of miscarriage. There was a higher risk of miscarriage in those women in the bed rest group than in those in the human chorionic gonadotrophin therapy group with no bed rest (RR 2.50, 95% CI 1.22 to 5.11). It seems that the small number of participants included in these studies is a main factor to make this analysis inconclusive.

Authors' conclusions

There is insufficient evidence of high quality that supports a policy of bed rest in order to prevent miscarriage in women with confirmed fetal viability and vaginal bleeding in first half of pregnancy.

Keywords: Female; Humans; Pregnancy; Bed Rest; Pregnancy, High-Risk; Abortion, Spontaneous; Abortion, Spontaneous/prevention & control; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Bed rest during pregnancy for preventing miscarriage

Not enough evidence to say if bed rest helps in preventing miscarriage.

Miscarriage is the loss of a baby before 23 weeks of pregnancy and this can cause much distress for parents. The most common treatment used to prevent it is probably bed rest. The review of two trials, involving 84 women, found that there was not enough evidence from good quality studies to be able to say whether bed rest helps to prevent miscarriage or not. Care for women at increased risk of miscarriage needs to be offered according to their individual needs.

Background

Miscarriage is pregnancy loss before 23 weeks of gestational age (WHO 1992) and it happens in 10% to 15% of pregnancies depending on maternal age and parity (Buckett 1997; Bulletti 1996; Schwarcz 1995). It is associated with chromosomal defects in about a half or two‐thirds of cases (Bricker 2000; Ogasawara 2000; Simpson 1987; Stern 1996), with maternal diseases (endocrinological, immunological, malformations of the genital tract, infections), or placental dysfunction (Cunningham 1993; Glass 1994).

Many interventions have been used for preventing miscarriage, depending on the disorder thought to be the etiological factor. Administration of hormones and immunotherapy are some of the examples. None of them have been proven to be effective (Clifford 1996; Goldstein 1989; Porter 2006).

Bed rest is probably the most commonly prescribed intervention for preventing miscarriage (Cunningham 1993; Schwarcz 1995), being mainly indicated in cases of threatened miscarriage (vaginal bleeding before 23 weeks of gestational age) but also in cases of a previous history of miscarriage (Goldenberg 1994). It is prescribed based on the idea that as hard work and hard physical activity during pregnancy are associated with miscarriage, bed rest might reduce the risk (Lapple 1990). However, this hypothesis is limited by the fact that most of the causes of miscarriage are not related to physical activity. Therefore, it seems unlikely that bed rest could play a significant role in the reduction of spontaneous miscarriage.

Vaginal bleeding before 23 weeks occurs in 25% of pregnancies (Stabile 1987), and once hemorrhage occurs, about half of the fetuses have no detectable cardiac activity (Everett 1987; Goldenberg 1994). The prescription of bed rest is probably futile in half of the cases of threatened abortion unless cardiac activity has been confirmed. In addition, bed rest may increase the likelihood of thromboembolic events (Kovacevich 2000), muscle atrophy and symptoms of musculoskeletal and cardiovascular deconditioning (Maloni 1993; Maloni 2002), may be stressful and costly for women and their family (Crowther 1995; Gupton 1997; Maloni 2001; May 1994), may induce self blame feelings in case of failure to comply with the prescription (Schroeder 1996) and may increase costs for the health services (Allen 1999; Goldenberg 1994; Schroeder 1996). It may also increase the time to completion of the miscarriage in inevitable losses, and affect maternal psychological adjustment. Since the effectiveness of some other interventions to prevent miscarriage have been assessed in other systematic reviews (Bamigboye 2003; Drakeley 2003; Haas 2008; Scott 1996) it is important to assess the effectiveness of bed rest to prevent miscarriage by reviewing the evidence from randomized controlled trials.

Objectives

To evaluate the effect of prescription of bed rest during pregnancy to prevent miscarriage in women at high risk of miscarriage.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All published, unpublished and ongoing randomized trials with reported data which compare clinical outcomes in pregnant women who were prescribed bed rest in hospital or at home for preventing miscarriage compared with alternative care or no intervention.

Types of participants

Pregnant women at high risk of miscarriage. 'High risk' includes women with either a previous history of miscarriage (fewer than three consecutive miscarriages) or threatened miscarriage in the current pregnancy. Studies including women with a history of recurrent miscarriage (three or more consecutive miscarriages) were not considered for this review since recurrent miscarriage may differ in some potential etiologic factors from simple spontaneous miscarriage (Creasy 2004).

Types of interventions

Prescription of bed rest at home or in hospital compared with alternative care or no intervention. Alternative care included any intervention prescribed for preventing miscarriage which did not include bed rest as part of it.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Fetal

Miscarriage Perinatal death or miscarriage Perinatal death (without malformations) or miscarriage Fetal death or miscarriage

Maternal

Thromboembolic events Maternal death

Secondary outcomes

Fetal

Miscarriage in the first trimester Miscarriage in the second trimester

Maternal

Thromboembolic events Time from enrolment to miscarriage Maternal satisfaction Psychological adjustment (e.g. depression) Costs

The outcomes were assessed in two comparisons:

bed rest versus no intervention;

bed rest versus alternative care.

Data were not available to perform the following subgroup analysis. Subgroups of participants:

threatened miscarriage or history of previous miscarriage;

first trimester miscarriage or second trimester miscarriage;

fetal cardiac activity confirmed at randomization or not.

Subgroups of intervention:

prescription of bed rest at home or in hospital.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register by contacting the Trials Search Co‐ordinator (March 2010).

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and contains trials identified from:

quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE;

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL and MEDLINE, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

For details of additional searching we undertook for the initial version of this review, seeAppendix 1.

We did not apply any language restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently assessed the inclusion criteria and methodological quality. Any disagreements were resolved by consensus or, if necessary, by a third author. We used the methods described in the Cochrane Reviewers' Handbook (Clarke 2000). Allocation concealment: (a) adequate concealment (b) uncertain (c) inadequate concealment.

Blinding and completeness of follow up were assessed for each outcome using the following criteria. For completeness of follow up: (a) less than 3% of participants excluded, (b) 3% to 9.9% of participants excluded, (c) 10% to 19.9% of participants excluded, (d) 20% or more of participants excluded. For blinding of outcome assessment: (a) single, (b) no blinding or blinding not mentioned.

The authors independently extracted data using a previously prepared data extraction form. The results are expressed as risk ratios and their 95% confidence intervals for dichotomous outcomes and mean difference with 95% confidence intervals for continuous outcomes, using the Cochrane Review Manager software (RevMan 2000). Studies were included irrespective of their methodological quality. We evaluated statistical heterogeneity across trials results using the Chi² test as calculated in MetaView. It was planned in the case of significant heterogeneity among study outcomes, that a sensitivity analysis would be performed, this was not required.

Results

Description of studies

Two trials that evaluated bed rest in pregnant women with vaginal bleeding in the first trimester have been identified and met the selection criteria. The trials involved 84 women.

One of the studies (Harrison 1993) randomly allocated 61 participants (pregnant women with vaginal bleeding, viable embryo certified by ultrasound, under eight weeks of gestational age) into three groups: bed rest (at home without sexual activity), placebo (ampoules with placebo liquid and without bed rest indication) and human chorionic gonadotrophin therapy (10,000 IU of initial dose administered parenterally followed by 5000 IU twice a week until 12 weeks of gestational age). The follow up was monthly visits (ultrasound and blood drawn at each visit) until the 16th week of gestational age followed by routine antenatal care. Data were obtained regarding complications during pregnancy and labor and final neonatal outcomes. In those women with miscarriage, curettage was carried out with histological analysis of material when possible.

The other study (Hamilton 1991) had two objectives, the first one was to study the ultrasound findings in pregnant women (between seven and 14 weeks of gestational age) with vaginal bleeding. The second objective was to perform a randomized controlled trial to study the effect of bed rest versus normal activity to prevent miscarriage. The inclusion criteria were pregnant women between seven and 14 weeks of gestational age, with vaginal bleeding within the previous 24 hours and viable embryo or fetus (certified by ultrasound). Twenty‐three women met the inclusion criteria and consented to participate in the study. These women were allocated randomly in one of three groups: bed rest at home (women were advised to stay in bed at home), bed rest and hospitalization (women were admitted into hospital and had bed rest during their stay) and normal activity (women went home and kept doing normal activity).

Risk of bias in included studies

Harrison's paper (Harrison 1993) does not give any information about the method used for randomization. Double blinding of the interventions (human chorionic gonadotrophin (HCG) and placebo) occurred in this trial. Bed rest was not blinded since it is not possible. No information about blinding of outcome assessments was given in the paper. In Harrison's study there were some women excluded after randomization. A group of women were recruited and randomized before the sixth week of gestational age without confirmation of a viable embryo so they had a second scan performed at the eighth week. When viability could not be confirmed at the eighth week's scan, owing to either a blighted ovum or an abortion already completed, these women were removed from the study and their randomization code number and treatment allocation were reallocated blindly by the author at a later time. This happened to nine women (three in active group, two in placebo group and four in bed rest group).

The table that shows the distribution of potential confounder variables among groups (in Harrison's original paper) shows clinical differences in frequency of primigravid women (HCG group: two; placebo group: seven; bed rest group: six) primiparous women (HCG group: four; placebo group: six; bed rest group: one) and in the number of previous abortions (HCG group: five; placebo group: two; bed rest group: two). There were no losses to follow up. The Hamilton paper (Hamilton 1991) does not describe the method used for randomization. Allocation concealment was not met and blinding of the interventions was not possible in this study. No information is given about blinding of outcome assessments. There were no exclusions after randomization or losses to follow up. The paper does not provide a table of distribution of potential confounder variables.

More details of these studies are given in the table of Characteristics of included studies.

Effects of interventions

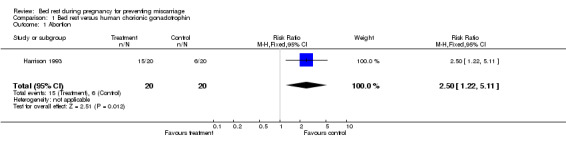

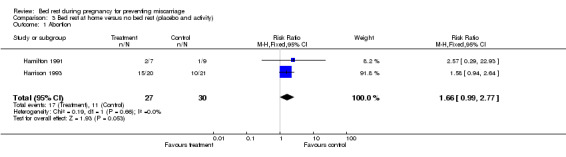

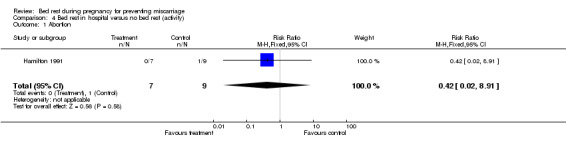

There was no significant difference in the risk of miscarriage in any of the following comparison groups: the bed rest group versus no bed rest group (that included women in placebo group from the Harrison study and women in normal activity group from the Hamilton study) (risk ratio (RR) 1.54, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.92 to 2.58); the bed rest at home group versus no bed rest (placebo group or activity group) (RR 1.66, 95% CI 0.99 to 2.77); or the bed rest in hospital group versus no bed rest (normal activity group since only Hamilton studied a group of hospitalized women) (RR 0.42, 95% CI 0.02 to 8.91). There was a higher risk of miscarriage in those women in the bed rest group than in the human chorionic gonadotrophin (HCG) group without bed rest (RR 2.50, 95% CI 1.22 to 5.11).

When analyzing mean gestational age at miscarriage (only assessed in Harrison's paper), miscarriage occurred earlier in the bed rest group than in the placebo group (12 weeks versus 13.5 weeks) and earlier in the HCG group than in the bed rest group (10 weeks versus 12 weeks). We are not able to report a confidence interval for these differences since the paper does not include raw data.

Discussion

There is a lack of evidence in this area since there are only two small trials that studied bed rest as an intervention to prevent miscarriage and these studies included only 84 women. One of the studies has three comparison groups including the administration of human chorionic gonadotrophin (HCG) without bed rest to prevent miscarriage (small numbers in each group makes comparison difficult).

Neither of the two trials evaluated potential side‐effects of bed rest. They did not assess how women and their families feel about this form of care. The information available in the literature suggests that many women find bed rest distressing and costly (in many ways) for them and their families. Similarly, there has been no long‐term follow up of developmental outcome of infants in any of the trials to date. There is currently no high‐quality evidence to support a policy of routine bed rest for women with confirmed fetal viability and vaginal bleeding in first half of pregnancy. There is no evidence of reduction in the risk of miscarriage in women prescribed bed rest. HCG administration as an alternative care for threatened miscarriage was more effective than bed rest in the Harrison study but this benefit is not confirmed when compared with placebo. Small numbers may account for the lack of significance. Further research is necessary to determine the real effect of HCG in preventing miscarriage in these women.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

There is not enough information to justify the recommendation of bed rest for women with threatened miscarriage or at high risk of miscarriage. There is currently no evidence to give reassurance that such a policy could not be harmful for women and their families since none of the studies assesses potential side‐effects of bed rest (thromboembolic events, maternal stress, depression, costs). Until further evidence is available the policy of bed rest cannot be recommended for routine clinical practice for women with threatened miscarriage or at high risk of miscarriage.

Implications for research.

Bed rest for threatened miscarriage was introduced into clinical practice without adequate controlled evaluation of its efficacy. The policy has been subjected to limited well‐controlled evaluation, and to clarify further the beneficial or adverse effects, additional, controlled evaluation is necessary. Evaluation of the policy in women considered at high risk of miscarriage (women with a threatened miscarriage or with a previous history of miscarriage excluding women with recurrent miscarriages) would seem appropriate. Also, a further assessment of the potential favorable effects of human chorionic gonadotrophin is necessary. Any future trials that study the effect of bed rest in women at high risk of miscarriage, should evaluate thromboembolic events, women's satisfaction, psychological adjustment and costs. Long‐term follow up of developmental outcome of infants should also be studied.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 23 April 2010 | New search has been performed | Search updated. No new trials identified. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 2002 Review first published: Issue 2, 2005

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 11 February 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 23 October 2007 | New search has been performed | Search updated. No new trial reports identified. |

| 17 January 2005 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

To Lynn Hampson, Trials Search Co‐ordinator of the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

As part of the pre‐publication editorial process, this review has been commented on by three peers (an editor and two referees who are external to the editorial team), one or more members of the Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's international panel of consumers and the Group's Statistical Adviser.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Additional searching for initial version of review

| Sources searched | Search strategy |

| The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (The Cochrane Library 2004, Issue 2). | #1 ABORTION*:ME #2 ABORTION* #3 MISCARRIAGE* #4 (THREATENED next ABORTION) #5 BED‐REST*:ME #6 (BED next REST) #7 REST* #8 BEDREST #9 (((#1 or #2) or #3) or #4) #10 (((#5 or #6) or #7) or #8) #11 (#9 and #10) |

| MEDLINE (1966 to July 2004) | Following a similar search strategy to above. |

| POPLINE (1982 to July 2004) | Following a similar search strategy to above. |

| LILACS (1982 to July 2004) | Following a similar search strategy to above. |

| EMBASE (1982 to July 2004) | Following a similar search strategy to above. |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Bed rest versus human chorionic gonadotrophin.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Abortion | 1 | 40 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.5 [1.22, 5.11] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Bed rest versus human chorionic gonadotrophin, Outcome 1 Abortion.

Comparison 2. Bed rest versus no bed rest (placebo and activity).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Abortion | 2 | 64 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.54 [0.92, 2.58] |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Bed rest versus no bed rest (placebo and activity), Outcome 1 Abortion.

Comparison 3. Bed rest at home versus no bed rest (placebo and activity).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Abortion | 2 | 57 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.66 [0.99, 2.77] |

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Bed rest at home versus no bed rest (placebo and activity), Outcome 1 Abortion.

Comparison 4. Bed rest in hospital versus no bed rest (activity).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Abortion | 1 | 16 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.42 [0.02, 8.91] |

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Bed rest in hospital versus no bed rest (activity), Outcome 1 Abortion.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Hamilton 1991.

| Methods | Random allocation at the time of first scan (the method is not mentioned). | |

| Participants | 23 women with viable pregnancies between 7 and 14 weeks who had experienced vaginal bleeding within the previous 24 hours. | |

| Interventions | Admission and bed rest in hospital, bed rest at home and normal activity at home. | |

| Outcomes | Miscarriage. | |

| Notes | Some of the data were not published in the paper, but were obtained through a letter written by the author to another researcher. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Harrison 1993.

| Methods | Random allocation (the method is not mentioned). Double‐blind was kept for placebo and HCG group. | |

| Participants | 61 women with a history of vaginal bleeding before the 8th week of gestational age (women with a history of habitual abortion or a potential cause for abortion were excluded). | |

| Interventions | Bed rest at home, placebo (without bed rest), 5000 IU of HCG i/m twice a week until 12th week and weekly until 16th week. | |

| Outcomes | Miscarriage (loss of pregnancy before 20 weeks of gestational age), mean gestational age in case of miscarriage, major maternal complication, neonatal death, type of delivery, sex and neonatal mean weight. | |

| Notes | Data on gestational age at miscarriage were not given "in full" in the paper, only the means were available without standard deviations. Treatment cycles of 30 women were initially completed but when the randomized codes were opened by sponsors severe discrepancies were found in group size so a second randomization code was prepared (blind to the author) to complete a sample of 61 women. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

HCG: human chorionic gonadotrophin i/m: intramuscular IU: international units

Contributions of authors

Alicia Aleman Riganti: design of protocol, writing draft protocol, revisions of draft protocol, search for identification of studies, analysis of literature, data analysis, writing final version of the review, revision of final version. Fernando Althabe: design of protocol, writing of draft protocol, revisions of draft protocol, revision of final version of the review, co‐ordination of review team and communication with the editorial base. Jose Belizan: design of protocol, writing of draft protocol, revisions of draft protocol, writing final version of the review. Eduardo Bergel: design of protocol, writing of draft protocol, revisions of draft protocol, analysis of literature, data analysis.

Sources of support

Internal sources

Latin American Center for Perinatology ‐ Pan American Health Organization ‐ World Health Organization, Uruguay.

External sources

National Institute of Health Fogarty International Center International Maternal and Child Health Training Grant 1D43 TW05492 02, USA.

Declarations of interest

None known.

New search for studies and content updated (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Hamilton 1991 {published and unpublished data}

- Hamilton RA, Grant AM, Henry OA, Eldurrija SM, Martin DH. The management of bleeding in early pregnancy. Irish Medical Journal 1991;84(1):18‐9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Harrison 1993 {published data only}

- Harrison RF. A comparative study of human chorionic gonadotropin, placebo and bed rest for women with early threatened abortion. International Journal of Fertility & Menopausal Studies 1993;38(3):160‐5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison RF. Abortion. Hormonal treatment with hCG [Avortement. Traitement hormonal par les hCG]. Contraception, Fertilite, Sexualite 1991;19(5):373‐6. [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Allen 1999

- Allen C, Glasziou P, Mar C. Bed rest: a potentially harmful treatment needing more careful evaluation. Lancet 1999;354:1229‐33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bamigboye 2003

- Bamigboye AA, Morris J. Oestrogen supplementation, mainly diethylstilbestrol, for preventing miscarriages and other adverse pregnancy outcomes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2003, Issue 3. [Art. No.: CD004353. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004353] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bricker 2000

- Bricker L, Garcia J, Henderson J, Mugford M. Ultrasound screening in pregnancy: a systematic review of the clinical effectiveness, cost‐effectiveness and women´s view. Health Technology Assessment 2000;4(16):1‐193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Buckett 1997

- Buckett W. The epidemiology of infertility in a normal population. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica 1997;76(3):233‐7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bulletti 1996

- Bulletti C, Flamigni C, Giacomucci E. Reproductive failure due to spontaneous abortion and recurrent miscarriage. Human Reproduction Update 1996;2(2):118‐36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Clarke 2000

- Clarke M, Oxman AD, editors. Cochrane Reviewers’ Handbook 4.1 [updated June 2000]. In: Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program]. Version 4.1. Oxford, England: The Cochrane Collaboration, 2000.

Clifford 1996

- Clifford K, Rai R, Watson H, Franks S, Regan L. Does suppressing luteinising hormone secretion reduce the miscarriage rate? Results of a randomised controlled trial. BMJ 1996;312(7045):1508‐11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Creasy 2004

- Hill J. Chapter 32: Recurrent pregnancy loss. In: Creasy R, Resnik R, Iams J editor(s). Maternal‐fetal medicine. Principles and practice. 5th Edition. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2004:579‐601. [Google Scholar]

Crowther 1995

- Crowther C, Chalmers I. Bed rest and hospitalization during pregnancy. In: Chalmers I, Enkin M, Keirse M editor(s). Effective care in pregnancy and childbirth. 1st Edition. Vol. 1, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995:625. [Google Scholar]

Cunningham 1993

- Cunningham F, McDonald P, Gant N, Leveno K, Gilstrap L. Williams obstetrics. 19th Edition. Norwalk, Connecticut: Appleton & Lange, 1993:661‐90. [Google Scholar]

Drakeley 2003

- Drakeley AJ, Roberts D, Alfirevic Z. Cervical stitch (cerclage) for preventing pregnancy loss in women. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2003, Issue 1. [Art. No.: CD003253. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003253] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Everett 1987

- Everett CB, Ashurst H, Chalmers I. Reported management of threatened miscarriage by general practitioners in Wessex. BMJ 1987;295:583‐6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Glass 1994

- Glass R, Golbus M. Recurrent abortion. In: Creasy R, Resnik R editor(s). Maternal and fetal medicine. 3rd Edition. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1994:445‐52. [Google Scholar]

Goldenberg 1994

- Goldenberg RL, Cliver SP, Bronstein J, Cutter GR, Andrews WW, Mennemeyer ST. Bed rest in pregnancy. Obstetrics & Gynecology 1994;84:131‐6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Goldstein 1989

- Goldstein P, Berrier J, Rosen S, Sacks HS, Chalmers TC. Meta‐analysis of randomized control trials of progestational agents in pregnancy. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 1989;96(3):265‐74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gupton 1997

- Gupton A, Heaman M, Ashcroft T. Bed rest from the perspective of the high‐risk pregnant woman. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic and Neonatal Nursing 1997;26(4):423‐30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Haas 2008

- Haas DM, Ramsey PS. Progestogen for preventing miscarriage. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2008, Issue 2. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003511.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kovacevich 2000

- Kovacevich GJ, Gaich SA, Lavin JP, Hopkins MP, Crane SS, Stewart J, et al. The prevalence of thromboembolic events among women with extended bed rest prescribed as part of the treatment for premature labor or preterm premature rupture of membranes. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 2000;182(5):1089‐92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lapple 1990

- Lapple M. Occupational factors in spontaneous miscarriage. Zentralblatt fur Gynakologie 1990;112(8):457‐66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Maloni 1993

- Maloni JA, Chance B, Zhang C, Cohen AW, Betts D, Gange SJ. Physical and psychosocial side effects of antepartum hospital bed rest. Nursing Research 1993;42(4):197‐203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Maloni 2001

- Maloni JA, Brezinski‐Tomasi JE, Johnson LA. Antepartum bed rest: effect upon the family. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic and Neonatal Nursing 2001;30(2):165‐73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Maloni 2002

- Maloni JA, Kane JH, Suen LJ, Wang KK. Dysphoria among high‐risk pregnant hospitalized women on bed rest: a longitudinal study. Nursing Research 2002;51(2):92‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

May 1994

- May KA. Impact of maternal activity restriction for preterm labor on the expectant father. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecology and Neonatal Nursing 1994;23(3):246‐51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ogasawara 2000

- Ogasawara M, Aoki K, Okada S, Suzumori K. Embryonic karyotype of abortuses in relation to the number of previous miscarriages. Fertility and Sterility 2000;73(2):300‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Porter 2006

- Porter TF, LaCoursiere Y, Scott JR. Immunotherapy for recurrent miscarriage. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2006, Issue 2. [Art. No.: CD000112. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000112.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

RevMan 2000 [Computer program]

- The Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager (RevMan). Version 4.1 for Windows. Oxford, England: The Cochrane Collaboration, 2000.

Schroeder 1996

- Schroeder C. Women´s experience of bed rest in high‐risk pregnancy. Image ‐ The Journal of Nursing Scholarship 1996;28(3):253‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schwarcz 1995

- Schwarcz RL, Duverges CA, Díaz AG, Fescina RH. Las hemorragias durante el embarazo. Obstetricia. 5th Edition. El Ateneo, Buenos Aires, 1995:174‐9. [Google Scholar]

Scott 1996

- Scott JR, Pattison N. Human chorionic gonadotrophin for recurrent miscarriage. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 1996, Issue 1. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000101.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Simpson 1987

- Simpson J, Bombard T. Chromosomal abnormalities in spontaneous abortion: frequency, pathology and genetic counselling. In: Edmonds K, Bennett M editor(s). Spontaneous abortion. Oxford: Blackwell, 1987. [Google Scholar]

Stabile 1987

- Stabile I, Cambell S, Grudinskas J. Ultrasound assessment of complications during first trimester of pregnancy. Lancet 1987;2:1237‐40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Stern 1996

- Stern J, Dorfman A, Gutierrez‐Najar A, Cerrillo M. Frequency of abnormal karyotypes among abortuses from women with and without a history of recurrent spontaneous abortion. Fertility and Sterility 1996;65(2):250‐3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

WHO 1992

- World Health Organization. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems. 10th Edition. Vol. 1, Geneva: World Health Organization, 1992. [Google Scholar]