Abstract

Background

Cervical cancer is one of the most common cancers in Taiwan. Some patients take Chinese herbal medicine (CHM). However, very few current studies have ascertained the usage and efficacy of CHM in patients with cervical cancer. The aim of this study was to investigate the benefits of complementary CHM among patients with cervical cancer in Taiwan.

Methods

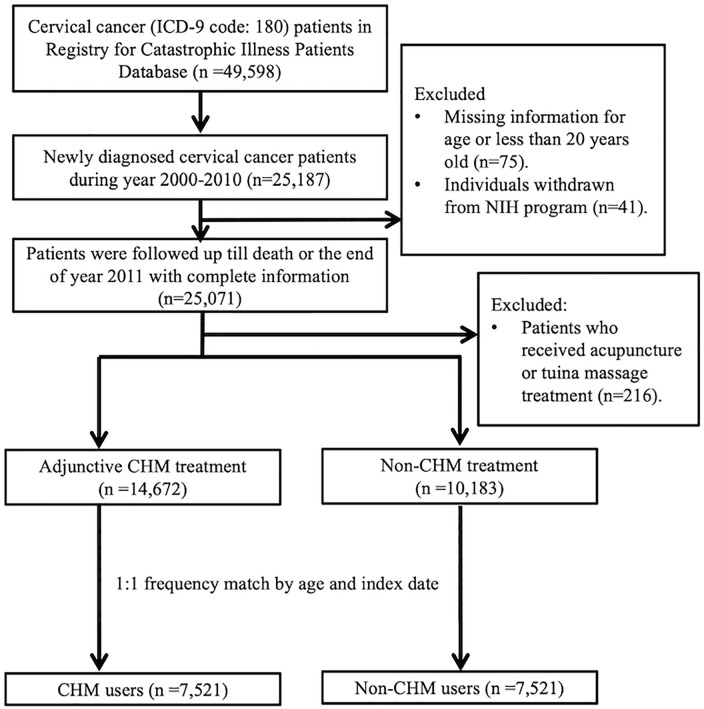

We included the newly diagnosed cervical cancer patients who were registered in the Taiwanese Registry for Catastrophic Illness Patients Database between 2000 and 2010. The end of follow-up period was December 31, 2011. Patients who were less than 20 years old, had missing information for age, withdrew from the National Health Insurance (NHI) program during the follow-up period, or only received other TCM interventions such as acupuncture or tuina massage were excluded from our study. After performing 1:1 frequency matching by age and index date, we enrolled 7521 patients in both CHM and non-CHM user groups. A Cox regression model was used to compare the hazard ratios (HRs) of the risk of mortality. The Kaplan-Meier curve was used to compare the difference in survival time.

Results

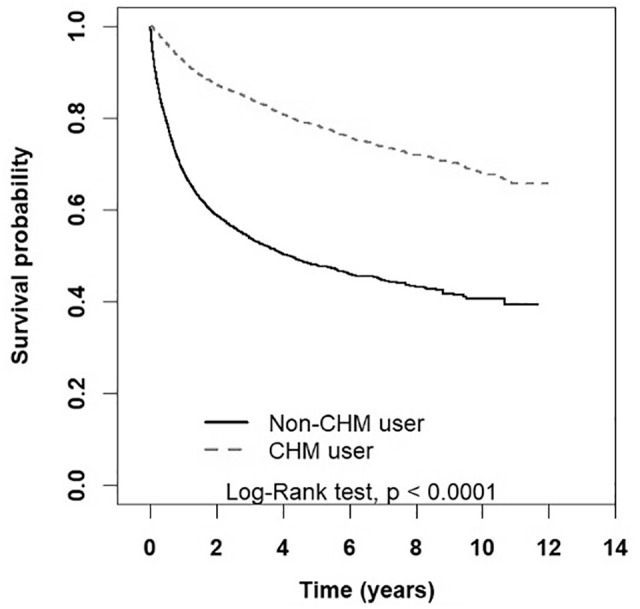

According to the Cox hazard ratio model mutually adjusted for CHM use, age, comorbidity, treatment, and chemotherapeutic agents used, we found that CHM users had a lower hazard ratio of mortality risk (adjusted HR = 0.29, 95%CI = 0.27-0.31). The survival probability was higher for patients in the CHM group. Bai-Hua-She-She-Cao (Herba Oldenlandiae, synonym Herba Hedyotis diffusae) and Jia-Wei-Xiao-Yao-San were the most commonly prescribed single herb and Chinese herbal formula, respectively.

Conclusions

Adjunctive CHM may have positive effects of reducing mortality rate and improving the survival probability for cervical cancer patients. Further evidence-based pharmacological investigations and clinical trials are warranted to confirm the findings in our study.

Keywords: cervical cancer, Chinese herbal medicine, integrative medicine, real-world evidence, traditional Chinese medicine, survival rate

Introduction

Cervical cancer is the third most commonly occurring cancer in women worldwide according to the latest global report. It accounted for 569 847 new cases and 311 365 cases of cancer-related mortality globally in 2018. 1 In Taiwan, the incidence of cervical cancer used to be fairly high, even exceeding the worldwide average.2,3 Owing to Pap smear screening program implemented by Health Promotion Administration (HPA) since 1995, the early diagnosis rate and mortality rate of invasive cervical cancer have improved.4,5 Based on the recent Taiwan’s official data, the incidence (excluding carcinoma in situ) and mortality rate of cervical cancer in 2016 were 12.11 and 5.36 per 100 000 population respectively. 6 Despite current multidisciplinary treatment strategies for cervical cancer including surgery, radiation therapy and chemotherapy, 7 disease stage is still regarded as the most important prognostic factor affecting survival for women with cervical cancer. 8 The 5-year survival rate sharply declined with stage on the basis of statistics from the American Cancer Society. 9

Cervical cancer undoubtedly is a significant health burden not only on cancer survivors but also on all of society. 10 For patients accepting conventional treatments, they often have to endure treatment-induced side effects, complications, and cumulative organ toxicities, which have negative impacts on the quality of life (QOL). 11 For worldwide societies, cervical cancer leads to considerable disability, premature death and enormous financial cost, thus exacerbating the cycle of poverty. 10 Interestingly, previous study revealed that the lower household income, the worse the QOL of cervical cancer survivors. 12 Therefore, combinations of conventional treatments with effective and economic therapies are urgently being investigated to improve clinical response and survival rate.

Chinese herbal medicine (CHM), a key treatment modality of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), has been practiced for thousands of years among Chinese communities. It has also been widely applied for adjuvant cancer treatment in Asian countries due to its anticancer effects proven by clinical response and evidence.13,14 Recently, more and more literature indicated that CHM could enhance immunomodulatory activities,15,16 inhibit carcinogenic properties, 17 prolong survival time,18-22 alleviate side effects of chemotherapy and radiotherapy, 13 and improve the quality of life 12 in cancer patients.

However, very few studies have put emphasis on the mortality rate of complementary utilization of CHM in patients with cervical cancer. One recently published meta-analysis included only 1 CHM clinical trial on patients diagnosed with cervical cancer. It is observed that the additional use of CHM significantly improved 1-year survival rate in cervical cancer patients. 23 Overall, for cervical cancer patients, at present there is insufficient evidence to conclude the effectiveness of CHM in prolonging long-term survival. Thus, we conducted this nationwide population-based retrospective cohort study in order to investigate the outcomes of CHM users with cervical cancer in Taiwan.

Materials and Methods

Data Sources

We used the Registry for Catastrophic Illness Patients Database (RCIPD), a part of the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) from the National Health Research Institutes in Taiwan, to perform this nationwide population-based cohort study. In Taiwan, the National Health Insurance (NHI) program was established in 1995. It covered more than 99% of the total population 24 and reimbursed western medical services as well as TCM services. All claims data, including de-identified (eg, sex and age) and clinical information (eg, diagnostic codes based on the International Classification of Disease, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM], health management and treatment), has been collected in the large computerized NHI database (NHIRD). RCIPD was then established by NHIRD, which enrolled all of the patients with catastrophic illness including 30 disease categories such as cancer, systemic autoimmune disease, and cerebral palsy. Registered cancer patients with catastrophic illness certificates are able to receive TCM or Western medical care without co-payment.

Our study acquired the data on cervical cancer patients from the RCIPD according to ICD-9-CM code 180. We included patients who were newly diagnosed with cervical cancer between January 2000 and December 2010 in Taiwan. The end of follow-up period was defined as December 31, 2011. Patients who were less than 20 years old, had missing information for age, withdrew from the NHI program during the follow-up period, or only received other TCM modalities such acupuncture or tuina massage were excluded from our study.

We defined CHM users as those had received CHM treatment after a confirmed diagnosis of cervical cancer. The index date was defined as the first time that patients received CHM treatment. We randomly assigned a date between the date of the diagnosis and the endpoint as the index date for the control group. The immortal time was referred to the period from the initial diagnosis of cervical cancer to the index date. We also used 1:1 frequency matching by age and index date to compare CHM users and non-CHM users.

Study Variables

We classified the patients into 3 groups by age: 20 to 39, 40 to 64, and more than 65 years old in order to investigate the differences among the various age groups. The comorbidities of these patients were determined by the following ICD-9-CM codes: diabetes mellitus (DM, ICD-9-CM 250), hypertension (ICD-9-CM 401–405), chronic kidney disease (CKD, ICD-9-CM 580–589), coronary artery disease (CAD, ICD-9-CM 414), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD, ICD-9-CM 490–496), cirrhosis (ICD-9-CM 571), and hyperlipidemia (ICD-9-CM 272). We also identified the patients who received hysterectomy for cervical cancer by treatment code.

Ethical Considerations

All of the datasets were de-identified and encrypted to protect enrollees’ privacy before being released for research. There was no possibility to identify individual patients from them. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of China Medical University and Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan (CMUH104-REC2-115).

Statistical Analysis

In this study, SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) was used for statistical analysis. For categorical variables, chi-square was used to identify the differences between CHM and non-CHM groups. For continuous variables, the independent t test was applied. Cox proportional hazard regression analysis with 95% confidence interval (CI) was performed to estimate crude and adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) of CHM use, age, comorbidity, conventional treatment, and specific chemotherapeutic agents used. We also used the Kaplan-Meier method to estimate the survival curves and the log rank test to evaluate the differences in survival time between 2 groups. A P value <.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Overall, between 2000 and 2011, there were 14 672 newly diagnosed patients with cervical cancer who have ever received CHM treatment after being confirmed diagnosis of cervical cancer. After performing 1:1 frequency matching by age and index date, which referred to the initial time of CHM use in CHM group, we included 7521 patients in both CHM and non-CHM user group (Figure 1). Clinical characteristics of the patients are listed in Table 1. The mean age of CHM and non-CHM user group were 57.6 and 57.9 respectively. CHM user group had higher percentage of comorbidities with coronary artery disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cirrhosis than non-CHM user group (P < .05). No significant difference was found in other comorbidities and treatments between 2 groups. The mean and median follow-up time of CHM user group were significantly longer than non-CHM user group (CHM user group: 4.15 and 3.15 years, non-CHM user group: 2.10 and 2.33 years).

Figure 1.

Recruitment flowchart of subjects from the Registry for Catastrophic Illness Patients Database (RCIPD) of the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) during the period 2000 to 2010 in Taiwan.

Abbreviations: CHM, Chinese herbal medicine.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Cervical Cancer Patients According to the Utilization of Chinese Herbal Medicine.

| Variable | Chinese herb medicine (CHM) | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (N = 7521) | Yes (N = 7521) | ||||

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Age mean ± SD (years) | 57.9 (13.8) | 57.6 (13.8) | .28 a | ||

| Age group | |||||

| 20-39 | 733 | 9.75 | 760 | 10.1 | .74 b |

| 40-64 | 4226 | 56.2 | 4224 | 56.2 | |

| ≥65 | 2562 | 34.1 | 2537 | 33.7 | |

| Comorbidity | |||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 1062 | 14.1 | 1103 | 14.7 | .34 a |

| Hypertension | 3208 | 42.7 | 3268 | 43.5 | .32 a |

| Chronic kidney disease | 947 | 12.6 | 986 | 13.1 | .34 a |

| Coronary artery disease | 1495 | 19.9 | 1631 | 21.7 | .01 a |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 1306 | 17.4 | 1436 | 19.1 | .01 a |

| Cirrhosis | 1326 | 17.6 | 1440 | 19.2 | .02 a |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1662 | 22.1 | 1735 | 23.1 | .15 a |

| Treatment | |||||

| Surgery | 36 | 0.48 | 37 | 0.49 | .91 a |

| Chemotherapy | 375 | 4.99 | 367 | 4.88 | .76 a |

| Cisplatin | 268 | 3.56 | 264 | 3.51 | .86 a |

| Paclitaxel | 50 | 0.66 | 48 | 0.64 | .84 a |

| Radiotherapy | 322 | 4.28 | 322 | 4.28 | .99 a |

| Interval between the initial diagnosis of cervical cancer and the index date, days, mean (median) | 654.3 (748.0) | 641.1 (742.9) | .27 b | ||

| Follow-up time, years, mean (median) | 2.10 (2.33) | 4.15 (3.15) | <.001 b | ||

Chi-square test.

t-test.

According to the Cox hazard ratio model mutually adjusted for CHM use, age, comorbidity, treatment, and chemotherapeutic agents used, we found that CHM users had a lower hazard ratio of mortality risk (adjusted HR = 0.29, 95% CI = 0.27-0.31) (Table 2). The mortality risk in ≥65-year-old group (adjusted HR = 2.40, 95% CI = 2.10-2.73) was significantly increased at more than twice that in the 20- to 39-year-old group. Patients with comorbidities including DM (adjusted HR = 1.34, 95% CI = 1.23-1.45) and CKD (adjusted HR = 1.77, 95% CI = 1.64-1.91) had higher mortality risk. We also found that patients receiving not only chemotherapy (adjusted HR = 1.74, 95% CI = 1.49-2.04) but also radiotherapy (adjusted HR = 1.31, 95% CI = 1.16-1.48) had higher hazard ratio.

Table 2.

Cox Model With Hazard Ratios and 95% Confidence Intervals of Mortality Associated With Chinese Herbal Medicine and Covariates Among Cervical Cancer Patients.

| Variable | Frequency of mortality (n = 4664) | Crude a | Adjusted b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | ||

| Chinese herbal medicine use | |||||

| No | 3171 | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | ||

| Yes | 1493 | 031 (0.29-0.33) | <.001 | 0.29 (0.27-0.31) | <.001 |

| Age group | |||||

| 20-39 | 290 | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | ||

| 40-64 | 2145 | 1.33 (1.18-1.51) | <.001 | 1.32 (1.17-1.50) | <.001 |

| ≥65 | 2229 | 2.40 (2.12-2.71) | <.001 | 2.40 (2.10-2.73) | <.001 |

| Comorbidity | |||||

| Diabetes mellitus | |||||

| No | 3810 | 1.00 (Reference) | <.001 | 1.00 (Reference) | <.001 |

| Yes | 854 | 1.43 (1.33-1.54) | 1.34 (1.23-1.45) | ||

| Hypertension | |||||

| No | 2353 | 1.00 (Reference) | <.001 | 1.00 (Reference) | .40 |

| Yes | 2311 | 1.32 (1.24-1.40) | 0.97 (0.90-1.04) | ||

| Chronic kidney disease | |||||

| No | 3759 | 1.00 (Reference) | <.001 | 1.00 (Reference) | <.001 |

| Yes | 905 | 1.83 (1.70-1.97) | 1.77 (1.64-1.91) | ||

| Coronary artery disease | |||||

| No | 3451 | 1.00 (Reference) | <.001 | 1.00 (Reference) | .11 |

| Yes | 1213 | 1.32 (1.23-1.40) | 1.06 (0.99-1.15) | ||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | |||||

| No | 3677 | 1.00 (Reference) | <.001 | 1.00 (Reference) | .57 |

| Yes | 987 | 1.21 (1.13-1.30) | 1.02 (0.95-1.10) | ||

| Cirrhosis | |||||

| No | 3792 | 1.00 (Reference) | .76 | ||

| Yes | 872 | 0.99 (0.92-1.06) | |||

| Hyperlipidemia | |||||

| No | 3663 | 1.00 (Reference) | .03 | ||

| Yes | 1001 | 0.93 (0.86-0.99) | |||

| Treatment | |||||

| Surgery | |||||

| No | 4635 | 1.00 (Reference) | .37 | ||

| Yes | 29 | 1.18 (0.82-1.70) | |||

| Chemotherapy | |||||

| No | 4206 | 1.00 (Reference) | <.001 | 1.00 (Reference) | <.001 |

| Yes | 458 | 2.08 (1.89-2.29) | 1.74 (1.49-2.04) | ||

| Cisplatin | |||||

| No | 4355 | 1.00 (Reference) | <.001 | 1.00 (Reference) | .31 |

| Yes | 309 | 1.94 (1.73-2.18) | 1.10 (0.92-1.31) | ||

| Paclitaxel | |||||

| No | 4585 | 1.00 (Reference) | <.001 | 1.00 (Reference) | <.001 |

| Yes | 79 | 2.69 (2.15-3.36) | 2.62 (2.09-3.28) | ||

| Radiotherapy | |||||

| No | 4301 | 1.00 (Reference) | <.001 | 1.00 (Reference) | <.001 |

| Yes | 363 | 1.79 (1.61-1.99) | 1.31 (1.16-1.48) | ||

Crude HR represents relative hazard ratio.

Adjusted HR represents adjusted hazard ratio: mutually adjusted through Cox proportional hazard regression model for CHM use, age group, comorbidities of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, coronary artery disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hyperlipidemia, treatment (including surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy), and chemotherapeutic agents used (including Cisplatin and Paclitaxel).

Based on the Kaplan-Meier curves, we found that the survival probability was higher for patients in the CHM group than for those in the non-CHM group (Figure 2). In Table 3, CHM users regardless of age, comorbidity and conventional treatment options had lower mortality risk than non-CHM users.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves of survival rate in cervical cancer patients of CHM and non-CHM group (log-rank test, P < .001).

Abbreviation: CHM, Chinese herbal medicine.

Table 3.

Incidence rates, Hazard Ratios, and Confidence Intervals of Mortality for Patients Stratified by Age Group, Comorbidity, Treatment, and Chemotherapeutic Agents Used.

| Variable | Chinese herb medicine used | Compared with Non-CHM user | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-CHM | CHM | Crude HR (95% CI) | Adjusted HR † (95% CI) | |||||

| Event | Person years | IR | Event | Person years | IR | |||

| Age group | ||||||||

| 20-39 | 220 | 1697 | 129.6 | 70 | 3274 | 21.4 | 0.22 (0.17-0.29)*** | 0.23 (0.17-0.30)*** |

| 40-64 | 1517 | 9343 | 162.4 | 628 | 17 250 | 36.4 | 0.29 (0.27-0.32)*** | 0.28 (0.26-0.31)*** |

| ≥65 | 1434 | 4815 | 297.8 | 795 | 10 691 | 74.4 | 0.31(0.29-0.34)*** | 0.31(0.28-0.33)*** |

| Comorbidity | ||||||||

| No | 1169 | 7220 | 161.9 | 475 | 12 575 | 37.8 | 0.31(0.27-0.34)*** | 0.30 (0.27-0.34)*** |

| Yes | 2002 | 8635 | 231.8 | 1018 | 18 640 | 54.6 | 0.30(0.28-0.32)*** | 0.29 (0.27-0.32)*** |

| Treatment | ||||||||

| Surgery | ||||||||

| No | 3151 | 15 785 | 199.6 | 1484 | 31 038 | 47.8 | 0.31 (0.29-0.33)*** | 0.30 (0.28-0.31)*** |

| Yes | 20 | 71 | 281.6 | 9 | 177 | 51.0 | 0.26 (0.11-0.58)** | 0.13 (0.05-0.37)** |

| Chemotherapy | ||||||||

| No | 2920 | 15 100 | 193.4 | 1286 | 29 878 | 43.0 | 0.29 (0.27-0.31)*** | 0.28 (0.26-0.30)*** |

| Yes | 251 | 756 | 332.2 | 207 | 1336 | 154.9 | 0.47 (0.39-0.57)*** | 0.47 (0.39-0.47)*** |

| Cisplatin | ||||||||

| No | 3004 | 15 333 | 195.9 | 1351 | 30 283 | 44.6 | 0.30 (0.28-0.32)*** | 0.28 (0.26-0.30)*** |

| Yes | 167 | 523 | 319.2 | 142 | 932 | 152.4 | 0.48 (0.38-0.60)*** | 0.49 (0.38-0.62)*** |

| Paclitaxel | ||||||||

| No | 3127 | 15 770 | 198.3 | 1458 | 31 063 | 46.9 | 0.30 (0.29-0 .32)*** | 0.29 (0.27-0.31)*** |

| Yes | 44 | 86 | 514.1 | 35 | 152 | 230.7 | 0.34 (0.21-0.57)*** | 0.39 (0.23-0.67)** |

| Radiotherapy | ||||||||

| No | 2954 | 15 170 | 194.7 | 1347 | 29 829 | 45.2 | 0.30 (0.28-0.32)*** | 0.29 (0.27-0.31)*** |

| Yes | 217 | 685 | 316.6 | 146 | 1386 | 105.4 | 0.37 (0.30-0.46)*** | 0.36 (0.29-0.45)*** |

Abbreviations: CHM, Chinese herbal medicine; IR, incidence rates per 1000 person-years; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Adjusted HR represents adjusted hazard ratio: mutually adjusted through Cox proportional hazard regression model for CHM use, age group, comorbidities (including diabetes mellitus, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, coronary artery disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hyperlipidemia), treatment (including surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy) and chemotherapeutic agents used (including Cisplatin and Paclitaxel).

**P < .01. ***P < .001.

Among the patients included, 7521 of them used CHMs after a confirmed diagnosis of cervical cancer. We identified the most commonly prescribed CHMs, which are shown in detail in Table 4. For single herbs, Bai-Hua-She-She-Cao (Herba Oldenlandiae, synonym Herba Hedyotis diffusae) was the most commonly used, followed by Da-Huang (Radix et Rhizoma Rhei) and Ban-Zhi-Lian (Herba Scutellriae Barbatae). For herbal formula, Jia-Wei-Xiao-Yao-San was the most commonly used, followed by Ma-Zi-Ren-Wan and Bu-Zhong-Yi-Qi-Tang. In addition, the highest dose of prescribed single herb and herbal formula were Dan-Shen (Radix Salviae Miltiorrhizae) and Xiang-Sha-Liu-Jun-Zi-Tang, respectively.

Table 4.

The Top 10 Most Common Usage of Chinese Herbal Medicine (CHM) for Patients With Cervical Cancer.

| CHM prescription | Frequency | Number of person (days) | Average daily dose (g) | Average duration for prescription (days) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single herbs | |||||

| Pin-yin name | Scientific name | ||||

| Bai-Hua-She-She-Cao | Herba Oldenlandiae (synonym Herba Hedyotidis Diffusae) | 2186 | 30 282 | 1.6 | 13.9 |

| Da-Huang | Radix et Rhizoma Rhei | 1674 | 18 874 | 0.7 | 11.3 |

| Ban-Zhi-Lian | Herba Scutellriae Barbatae | 1441 | 20 275 | 1.7 | 14.1 |

| Dan-Shen | Radix Salviae Miltiorrhizae | 1057 | 12 299 | 2.6 | 11.6 |

| Bai-Zhu | Rhizoma Atractylodis macrocephalae | 1033 | 10 966 | 1.5 | 10.6 |

| Gan-Cao | Radix Glycyrrhizae Uralensis | 1010 | 11 400 | 2.2 | 11.3 |

| Hou-Po | Cortex Magnoliae officinalis | 966 | 9883 | 1.1 | 10.2 |

| Bei-Mu | Bulbus Fritillariae | 881 | 8307 | 2.1 | 9.4 |

| Hai-Piao-Xiao | Os Sepiae seu Sepiellae | 875 | 9076 | 2.0 | 10.4 |

| Zhi-Shi | Fructus Immaturus Citri Aurantii | 839 | 8128 | 1.1 | 9.7 |

| Chinese herbal formulas | |||||

| Jia-Wei-Xiao-Yao-San | 1625 | 22 029 | 4.7 | 13.6 | |

| Ma-Zi-Ren-Wan | 1087 | 12 185 | 2.9 | 11.2 | |

| Bu-Zhong-Yi-Qi-Tang | 922 | 11 631 | 4.3 | 12.6 | |

| Xiang-Sha-Liu-Jun-Zi-Tang | 833 | 9600 | 7.0 | 11.5 | |

| Gui-Pi-Tang | 720 | 8202 | 6.2 | 11.4 | |

| Sheng-Mai-San | 629 | 6696 | 4.2 | 10.6 | |

| San-Zhong-Kui-Jian-Tang | 580 | 6663 | 4.2 | 11.5 | |

| Dang-Gui-Shao-Yao-San | 559 | 5574 | 4.2 | 10.0 | |

| Suan-Zao-Ren-Tang | 543 | 6086 | 4.2 | 11.2 | |

| Qi-Ju-Di-Huang-Wan | 536 | 8660 | 3.9 | 16.2 | |

Discussion

Our study mainly found that integrative CHM treatment may be beneficial for patients with cervical cancer. Regardless of age, comorbidity, and conventional treatment options, CHM users had much lower mortality risk than non-CHM users. The survival probability was higher for patients in the CHM group. Our findings were partially in accordance with a previous systematic review which reported that additional CHM treatment improved patients’ 1-year survival rate significantly when compared to radiotherapy or chemotherapy alone (pooled OR = 4.16, 95% CI = 1.97-8.78). 23 Based on the positive effects proved by former literature and our study, adjuvant CHM therapy could be considered as an available and useful strategy for the treatment of cervical cancer.

With the strength of big data analytics, this study is a large-scale retrospective cohort study to investigate the outcomes of CHM users with cervical cancer in Taiwan. We used RCIPD as our dataset, which provided the nationwide population-based information in Taiwan. Therefore, the potential for selection bias could be minimized due to the real-world data assessed from the NHI program. Moreover, most previous studies of the utilization of CHM in cervical cancer focused on either the effects of the specific herbs25-27 or formulas 28 in vitro and in vivo. The comprehensive benefits of complementary Chinese herbal medicine use among patients with cervical cancer have rarely been reported. Our study appears to be the initial investigation of this issue. In our study, we also performed 1:1 frequency matching by age and index date, which referred to the initial time of CHM use instead of the time of newly diagnosed with cervical cancer. The immortal time bias could be partially avoided in this manner.

Cancer is regarded as a life-threatening issue for our and future generations. 29 According to the previous population-based study reported in Lancet Oncology, the predicted incidence of all cancers may increase significantly from 12.7 million new cases in 2008 to 22.2 million by 2030 all over the world. 30 Besides, cancer care is also a global health priority due to the growing number of aging populations with increasing prevalence of cancer. 31 The optimal effects of treatment involve improving life quality, prolonging survival time and alleviating side effects. In terms of cervical cancer, surgery remains the first treatment option for the majority of early stage patients while concurrent chemo-radiotherapy (CCRT), palliative chemotherapy, and target therapy are used in the management of advanced stage. 7 However, a series of complications and side effects such as fatigue, pain, neurological bladder, 32 nausea and vomiting, 33 edema, and bone marrow suppression 34 may result in discomfort and inconvenience, which often restrict the application and effectiveness of cancer treatment.

CHM, which is seen to have relatively fewer side effects, has been proposed to be an effective and affordable adjuvant cancer treatment in different stages of cancer lesions in view of limitations in conventional cancer care. 14 As we shown in Table 4, Bai-Hua-She-She-Cao (Herba Oldenlandiae, synonym Herba Hedyotis diffusae) and Ban-Zhi-Lian (Herba Scutellriae Barbatae) were commonly used single herbs in cervical cancer in our study. Bai-Hua-She-She-Cao and its active constituents have been revealed a variety of pharmacological activities recently, including anticancer, chemopreventive, hepatoprotective, antiviral, antibacterial, antidiabetic, antioxidant, and gastroprotective properties. 35 In the past few years, it has widely applied in cancer therapy such as colorectal,36-38 liver, 39 lung, 40 prostate, 41 and other cancers due to several potential anticancer effects. For instance, the extract of Bai-Hua-She-She-Cao and its active constituents have been reported to induce cell morphological changes, reduce cell viability, lead to DNA fragmentation, loss of plasma membrane asymmetry, activate caspase-9 and caspase-3 and so on. 42 We have also shown that its extract and active compound, rutin, can be used as an adjuvant in peptide-based vaccines to increase immunogenicity against human papillomavirus (HPV)-induced cervical cancer. 16 Ban-Zhi-Lian and its active constituents also have been used as an antitumor herb in several cancers.43-45 The mechanism underlying its anticancer activity appears to involve DNA damage, cell cycle control, nucleic acid binding, protein phosphorylation and dephosphorylation and dendritic cell functions on the basis of cDNA microarray analysis.46,47 Besides, Ban-Zhi-Lian and its active constituents could effectively improve the side effects of chemo- or radiotherapy such as dysfunction of liver, diarrhea, fatigue, and pain. 48 As the results revealed in our study, Jia-Wei-Xiao-Yao-San was the most commonly used herbal formula in cervical cancer. It has been frequently administered concurrently with chemotherapy, contributing to 1 of the top 3 prescribed formulations for breast, colon and gastric cancer patients in Taiwan. 49 Interestingly, according to the previous nationwide population-based study, cervical cancer is a prominent risk factor for developing depression following diagnosis in Taiwan. 5 This finding revealed by Shyu et al may account for the common prescription of Jia-Wei-Xiao-Yao-San which has been widely used to treat neuropsychological disorders based on the “liver depression and qi stagnation” of TCM syndrome. Furthermore, we found the precipitating medicine including Da-Huang (Radix et Rhizoma Rhei) and Ma-Zi-Ren-Wan were commonly used in our study. These findings confirmed that constipation is a common bowel symptom associated with radical pelvic surgeries and pelvic radiation for gynecologic cancer.50,51 For survivors who were 1 year post-treatment of cervical and endometrial cancer, nearly 60% of them have suffered from constipation according to a previous US study. 52 In brief, although several CHMs mentioned above have implied effectiveness in cancer therapy, their precise mechanism still remains to be clarified.

In our study, we also found that the mortality risk in ≥65-year-old group was much higher than the other 2 groups. The finding was consistent with the previous studies due to the 2 main reasons. On one hand, Kau et al 3 disclosed that the incidence of cervical cancer in Taiwan is increasing with age, which might be attributable to the lower percentage of elderly women receiving the Pap tests 53 which leads to more advanced disease at diagnosis. 54 On the other hand, for older patients with cancer, the existence of comorbidities is common, which may influence prognosis, treatment choice, and overall survival.55,56 Although an earlier study showed that comorbidity was an independent predictor of survival in women with either early or late stage cervical cancer, 57 our findings indicated cervical cancer patients with comorbidity of DM and CKD had higher mortality risk. Because of the fact that Taiwan has the relatively higher prevalence of DM 58 and CKD 59 than the global average, cervical cancer patients with these 2 comorbidities are required to struggle with not only cancer therapies but also the multiple complications of DM and CKD. Certainly, DM and CKD contributed to the higher risk of all-cause mortality compared with patients without these 2 comorbidities.60,61 Comorbidity may also limit treatment options of cervical cancer and increase the risk of treatment complications. 62 In addition, we also found that cervical cancer patients receiving not only chemotherapy but also radiotherapy had higher mortality hazard ratio. The result implied that advanced stage cervical cancer compared with early stage had poor prognosis. Due to the treatment options depending on the stage of cervical cancer, patients with advanced stage disease were prone to undergo the chemo- or radiotherapy while patients with early stage disease generally received surgery.

Our study had several limitations. First of all, we were unable to access the complete and detailed information noted in the electronic medical records of hospitals and clinics. Although we tried to match the 2 groups, FIGO staging, histological types and performance status were not provided in our datasets. Second, other factors affecting mortality of cervical cancer such as socioeconomic status, lifestyle, exercise habits and motivation could not be estimated in our study. Third, as only the herbal concentrate-granules are covered by NHI payment in Taiwan, patients who used natural product supplements or self-paid herbal decoctions without clinic visits were excluded from our study due to the lack of records of NHIRD. Lastly, despite the reduction in the hazard ratio of CHM use revealed in our study, we were not capable of proving how long the CHM use might conduce to those benefits for cervical cancer patients. Future studies aimed to provide detailed information of CHM use, including the cumulative dose effects, are warranted.

Conclusion

In summary, adjunctive Chinese herbal medicine may have positive effect of reducing mortality rate in cervical cancer patients regardless of age, comorbidity and treatment. For long-term survival, the utilization of Chinese herbal medicine could improve the survival probability. Integrative treatment with Chinese herbal medicine might be recommended as an effective strategy for cervical cancer patients. Further evidence-based pharmacological investigations and clinical trials are needed to confirm the findings in our study.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was financially supported by the “Chinese Medicine Research Center, China Medical University” from the Featured Areas Research Center Program within the framework of the Higher Education Sprout Project by the Ministry of Education (MOE) in Taiwan (CMRC-CHM-2). This study was also supported in part by China Medical University (CMU107-TU-04), China Medical University Hospital (DMR-110-002, DMR-109-193 and DMR-109-194), Ministry of Health and Welfare Clinical Trial Center (MOHW110-TDU-B-212-124004), and health and welfare surcharge of tobacco products, China Medical University Hospital Cancer Research Center of Excellence, Ministry of Health and Welfare (MOHW110-TDU-B-212-144024), Taiwan. None of the funders and institutions listed had a role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

ORCID iD: Hung-Rong Yen  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0131-1658

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0131-1658

References

- 1. Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I, et al. Estimating the global cancer incidence and mortality in 2018: GLOBOCAN sources and methods. Int J Cancer. 2019;144:1941-1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Forouzanfar MH, Foreman KJ, Delossantos AM, et al. Breast and cervical cancer in 187 countries between 1980 and 2010: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2011;378:1461-1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kau Y-C, Liu F-C, Kuo C-F, et al. Trend and survival outcome in Taiwan cervical cancer patients: a population-based study. Medicine. 2019;98:e14848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chen YY, You SL, Chen CA, et al. Effectiveness of national cervical cancer screening programme in Taiwan: 12-year experiences. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:174-177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shyu IL, Hu L-Y, Chen Y-J, Wang PH, Huang BS. Risk factors for developing depression in women with cervical cancer: a nationwide population-based study in Taiwan. Int J Womens Health. 2019;11:135-141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Health Promotion Administration Ministry of Health and Welfare. Cancer Registry annual report, 2016 Taiwan; 2018:70. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Koh W-J, Abu-Rustum NR, Bean S, et al. Cervical cancer, version 3.2019, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2019;17:64-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Quinn MA, Benedet JL, Odicino F, et al. Carcinoma of the cervix uteri. FIGO 26th annual report on the results of treatment in gynecological cancer. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2006;95:S43-S103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al. SEER cancer statistics review, 1975-2016. National Cancer Institute. Accessed February 5, 2019. https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2016 [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ginsburg O, Bray F, Coleman MP, et al. The global burden of women’s cancers: a grand challenge in global health. Lancet. 2017;389:847-860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tsai L-Y, Lee S-C, Wang K-L, Tsay SL, Tsai JM. A correlation study of fear of cancer recurrence, illness representation, self-regulation, and quality of life among gynecologic cancer survivors in Taiwan. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;57:846-852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Huang H-Y, Tsai W-C, Chou W-Y, et al. Quality of life of breast and cervical cancer survivors. BMC Womens Health. 2017;17:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Qi F, Li A, Inagaki Y, et al. Chinese herbal medicines as adjuvant treatment during chemoor radio-therapy for cancer. Biosci Trends. 2010;4:297-307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Qi F, Zhao L, Zhou A, et al. The advantages of using traditional Chinese medicine as an adjunctive therapy in the whole course of cancer treatment instead of only terminal stage of cancer. Biosci Trends. 2015;9:16-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fleischer T, Chang TT, Chiang JH, Yen HR. A controlled trial of Sheng-Yu-Tang for post-hematopoietic stem cell transplantation leukemia patients: a proposed protocol and insights from a preliminary pilot study. Integr Cancer Ther. 2018;17:665-673. doi: 10.1177/1534735418756736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Song YC, Huang HC, Chang CY, et al. A potential herbal adjuvant combined with a peptide-based vaccine acts against HPV-Related tumors through enhancing effector and memory T-cell immune responses. Front Immunol. 2020;11:62. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Song YC, Hung KF, Liang KL, et al. Adjunctive Chinese herbal medicine therapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma: clinical evidence and experimental validation. Head Neck. 2019;41:2860-2872. doi: 10.1002/hed.25766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fleischer T, Chang TT, Chiang JH, Sun MF, Yen HR. Improved survival with integration of Chinese herbal medicine therapy in patients with acute myeloid leukemia: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Integr Cancer Ther. 2017;16:156-164. doi: 10.1177/1534735416664171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Huang CY, Wu MY, Kuo YH, Tou SI, Yen HR. Chinese herbal medicine Is helpful for survival improvement in patients with multiple myeloma in Taiwan: a nationwide retrospective matched-cohort study. Integr Cancer Ther. 2020;19:1534735420943280. doi: 10.1177/1534735420943280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hung KF, Hsu CP, Chiang JH, et al. Complementary Chinese herbal medicine therapy improves survival of patients with gastric cancer in Taiwan: a nationwide retrospective matched-cohort study. J Ethnopharmacol. 2017;199:168-174. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2017.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kuo YT, Chang TT, Muo CH, et al. Use of complementary traditional Chinese medicines by adult cancer patients in Taiwan: a nationwide population-based study. Integr Cancer Ther. 2018;17:531-541. doi: 10.1177/1534735417716302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kuo YT, Liao HH, Chiang JH, et al. Complementary Chinese herbal medicine therapy improves survival of patients with pancreatic cancer in Taiwan: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Integr Cancer Ther. 2018;17:411-422. doi: 10.1177/1534735417722224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chung VC, Wu X, Hui EP, et al. Effectiveness of Chinese herbal medicine for cancer palliative care: overview of systematic reviews with meta-analyses. Sci Rep. 2015;5:18111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. National Health Insurance Administration Ministry of Health and Welfare. National Health Insurance Annual Report 2014–2015. Ministry of Health and Welfare Taipei; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ding W, Ji T, Xiong W, Li T, Pu D, Liu R. Realgar, a traditional Chinese medicine, induces apoptosis of hPV16-positive cervical cells through a hPV16 e7-related pathway. Drug Des Dev Ther. 2018;12:3459-3469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zuo HJ, Liu S, Yan C, Li LM, Pei XF. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of antitumor activity of Ligustrum robustum, a Chinese herbal tea. Chin J Integr Med. 2019;25:425-430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhang M, Yu Y, Zhang H, et al. Synergistic cytotoxic effects of a combined treatment of a Pinellia pedatisecta lipid-soluble extract and cisplatin on human cervical carcinoma in vivo. Oncol Lett. 2017;13:4748-4754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Li M, Hu S, Chen X, Wang R, Bai X. Research on major antitumor active components in Zi-Cao-Cheng-Qi decoction based on hollow fiber cell fishing with high performance liquid chromatography. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2018;149:9-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Adams C, Grey N, Magrath I, Miller A, Torode J. The World Cancer Declaration: is the world catching up? Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:1018-1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bray F, Jemal A, Grey N, Ferlay J, Forman D. Global cancer transitions according to the Human Development Index (2008-2030): a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:790-801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ferris FD, Bruera E, Cherny N, et al. Palliative cancer care a decade later: accomplishments, the need, next steps—from the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3052-3058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Landoni F, Maneo A, Colombo A, et al. Randomised study of radical surgery versus radiotherapy for stage Ib-IIa cervical cancer. Lancet. 1997;350:535-540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Peters WA, Liu PY, Barrett RJ, et al. Concurrent chemotherapy and pelvic radiation therapy compared with pelvic radiation therapy alone as adjuvant therapy after radical surgery in high-risk early-stage cancer of the cervix. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2000;55:491-492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Moore DH, Blessing JA, McQuellon RP, et al. Phase III study of cisplatin with or without paclitaxel in stage IVB, recurrent, or persistent squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix: a gynecologic oncology group study. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3113-3119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Niu Y, Meng Q-X. Chemical and preclinical studies on Hedyotis diffusa with anticancer potential. J Asian Nat Prod Res. 2013;15:550-565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Liu X, Wu J, Zhang D, Wang K, Duan X, Zhang X. A network pharmacology approach to uncover the multiple mechanisms of Hedyotis diffusa Willd. on colorectal cancer. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2018;2018:1-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sun G, Wei L, Feng J, Lin J, Peng J. Inhibitory effects of Hedyotis diffusa Willd. on colorectal cancer stem cells. Oncol Lett. 2016;11:3875-3881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lin J, Li Q, Chen H, Lin H, Lai Z, Peng J. Hedyotis diffusa Willd. extract suppresses proliferation and induces apoptosis via IL-6-inducible STAT3 pathway inactivation in human colorectal cancer cells. Oncol Lett. 2015;9:1962-1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Li YL, Zhang J, Min D, Hongyan Z, Lin N, Li QS. Anticancer effects of 1,3-dihydroxy-2-methylanthraquinone and the ethyl acetate fraction of Hedyotis diffusa Willd against HepG2 carcinoma cells mediated via apoptosis. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0151502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Su X, Li Y, Jiang M, et al. Systems pharmacology uncover the mechanism of anti-non-small cell lung cancer for Hedyotis diffusa Willd. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019;109:969-984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hu E, Wang D, Chen J, Tao X. Novel cyclotides from Hedyotis diffusa induce apoptosis and inhibit proliferation and migration of prostate cancer cells. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:4059-4065. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lin J, Chen Y, Wei L, et al. Hedyotis diffusa Willd extract induces apoptosis via activation of the mitochondrion-dependent pathway in human colon carcinoma cells. Internet J Oncol. 2010;37:1331-1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zhang L, Ren B, Zhang J, et al. Anti-tumor effect of Scutellaria barbata D. Don extracts on ovarian cancer and its phytochemicals characterisation. J Ethnopharmacol. 2017;206:184-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sun P, Sun D, Wang X. Effects of Scutellaria barbata polysaccharide on the proliferation, apoptosis and EMT of human colon cancer HT29 cells. Carbohydr Polym. 2017;167:90-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pan L-T, Sheung Y, Guo W-P, Rong ZB, Cai ZM. Hedyotis diffusa plus Scutellaria barbata induce bladder cancer cell apoptosis by inhibiting Akt signaling pathway through downregulating miR-155 expression. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2016;2016:1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wang M, Chen Y, Hu P, Ji J, Li X, Chen J. Neoclerodane diterpenoids from Scutellaria barbata with cytotoxic activities. Nat Prod Res. 2020;34:1345-1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Nie X-P, Qu GW, Yue X-D, Li GS, Dai SJ. Scutelinquanines A–C, three new cytotoxic neo-clerodane diterpenoid from Scutellaria barbata. Phytochem Lett. 2010;3:190-193. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Perez AT, Arun B, Tripathy D, et al. A phase 1B dose escalation trial of Scutellaria barbata (BZL101) for patients with metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;120:111-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Cheng Y-Y, Hsieh C-H, Tsai T-H. Concurrent administration of anticancer chemotherapy drug and herbal medicine on the perspective of pharmacokinetics. J Food Drug Anal. 2018;26:S88-S95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Abayomi J, Kirwan J, Hackett A. The prevalence of chronic radiation enteritis following radiotherapy for cervical or endometrial cancer and its impact on quality of life. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2009;13:262-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hazewinkel MH, Sprangers MA, van der Velden J, et al. Long-term cervical cancer survivors suffer from pelvic floor symptoms: a cross-sectional matched cohort study. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;117:281-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Donovan KA, Boyington AR, Judson PL, Wyman JF. Bladder and bowel symptoms in cervical and endometrial cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology. 2014;23:672-678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Lee FH, Wang HH. The utilization of Pap test services of women: a nationwide study in Taiwan. Cancer Nurs. 2011;34:464-469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Fleming ST, Pursley HG, Newman B, Pavlov D, Chen K. Comorbidity as a predictor of stage of illness for patients with breast cancer. Med Care. 2005;43:132-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Jørgensen TL, Hallas J, Friis S, Herrstedt J. Comorbidity in elderly cancer patients in relation to overall and cancer-specific mortality. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:1353-1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Extermann M. Measurement and impact of comorbidity in older cancer patients. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2000;35:181-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Leath CA, 3rd, Straughn JM, Jr, Kirby TO, Huggins A, Partridge EE, Parham GP. Predictors of outcomes for women with cervical carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;99:432-436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hou W-H, Li C-Y, Chang H-H, Sun Y, Tsai CC. A population-based cohort study suggests an increased risk of multiple sclerosis incidence in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Epidemiol. 2017;27:235-241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Tsai M-H, Hsu C-Y, Lin M-Y, et al. Incidence, prevalence, and duration of chronic kidney disease in Taiwan: results from a community-based screening program of 106,094 individuals. Nephron. 2018;140:175-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Yang JJ, Yu D, Wen W, et al. Association of diabetes with all-cause and cause-specific mortality in Asia. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e192696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Wen CP, Cheng TY, Tsai MK, et al. All-cause mortality attributable to chronic kidney disease: a prospective cohort study based on 462 293 adults in Taiwan. Lancet. 2008;371:2173-2182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Sarfati D, Koczwara B, Jackson C. The impact of comorbidity on cancer and its treatment. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:337-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]