Abstract

Our purpose is to assess the role of deep medullary veins (DMVs) in pathogenesis of MRI-visible perivascular spaces (PVS) in patients with cerebral small vessel disease (cSVD). Consecutive patients recruited in the CIRCLE study (ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT03542734) were included. Susceptibility Weighted Imaging-Phase images were used to evaluate DMVs based on a brain region-based visual score. T2 weighted images were used to evaluate PVS based on the five-point score, and PVS in basal ganglia (BG-PVS), centrum semiovale (CSO-PVS) and hippocampus (H-PVS) were evaluated separately. 270 patients were included. The severity of BG-PVS, CSO-PVS and H-PVS was positively related to the increment of age (all p < 0.05). The severity of BG-PVS and H-PVS was positively related to DMVs score (both p < 0.05). Patients with more severe BG-PVS had higher Fazekas scores in both periventricle and deep white matter (both p < 0.001) and higher frequency of hypertension (p = 0.008). Patients with more severe H-PVS had higher frequency of diabetes (p < 0.001). Besides, high DMVs score was an independent risk factor for more severe BG-PVS (β = 0.204, p = 0.001). Our results suggested that DMVs disruption might be involved in the pathogenesis of BG-PVS.

Keywords: MRI-visible perivascular spaces, deep medullary veins, basal ganglia, centrum semiovale, hippocampus, susceptibility weighted imaging

Introduction

Perivascular spaces (PVS) are identified as the spaces that surround small blood vessels in the brain, which have been proved to play an important role in the clearance of interstitial fluid and waste from the brain. 1 PVS are invisible on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at conventional field strengths and become visible when enlarged. MRI-visible perivascular spaces (PVS) appear as punctate or linear hyperintensities, iso-intense with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) on T2-weighted MRI. 2 Previous researches including human studies and rodent models demonstrated that PVS contributed to the maintenance of brain health and PVS could be associated with several neurological disorders. 1

PVS were proved to be associated with several factors, including vascular pulsation, respiratory movement, the sleep–wake cycle and aquaporin-4 (AQP4) water channels on astrocyte end feet. 1 However, their relationship with veins were rarely mentioned. Indeed, venous disruption was demonstrated to be closely connected with the integrity of blood brain barrier (BBB) and decreased cerebral blood flow (CBF), which were associated with PVS as well.2–4 Besides, histopathological studies have revealed that venous collagenosis played an important role in the development of cerebral small vessel disease (cSVD), 5 such as white matter hyperintensities (WMHs) and lacunar infarcts. 6 , 7 It is thus rational to assume that venous disruption may be involved in the pathogenesis of PVS, given that PVS are considered as an important imaging biomarker of cSVD.

PVS are usually seen in specific brain regions: basal ganglia and centrum semiovale. The presence of PVS in basal ganglia are mostly related to hypertension, lacunar stroke and dementia,8–14 while those in centrum semiovale seem to indicate cerebral amyloid angiopathy. 15 Therefore, in this study, aiming to address the relationship between PVS and venous disruption, we further investigated whether the role of venous insufficiency was different in the pathogenesis of PVS in different regions. Visual deep medullary veins (DMVs) scoring system on susceptibility weighted imaging (SWI) was used, which have already been shown to indicate the extent of venous disruption in brain in previous studies. 16 , 17

Materials and methods

Study subjects

We retrospectively reviewed the data of consecutive patients recruited in the CIRCLE study (ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT03542734) between January 2017 and June 2020. The CIRCLE study is a single-center prospective observational study that enrolls adults (age >40) with and without cSVD and free of known dementia or stroke, who will then undergo neuropsychological test, retinal digital images and multimodal MRI scan. For the current study, we included patients in CIRCLE study who also met the additional inclusion criteria: (1) T2, T2 Fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) and SWI sequences performed; (2) cSVD imaging markers (WMHs with Fazekas score 1–3 in periventricular or deep white matter, or at least one lacuna or one microbleed) visible on MRI; (3) at least six months after the onset of stroke in patients with acute lacunar stroke; (4) without secondary causes of white matter lesions, such as demyelinating, metabolic, immunological, toxic, infectious, and other causes. The exclusion criteria were: (1) any MRI contraindications; (2) serious head injury (resulting to loss of consciousness) or received intracranial surgery; (3) suffering from cancer; (4) abnormal brain MRI findings such as head trauma, hemorrhage, non-lacunar infarction and other space-occupying lesions; (5) definitive peripheral neuropathy and spinal cord disease; (6) calcification on CT scans or encephalomalacia in the deep gray matter structures since it may influence the observation of DMVs. (7) suffering from dementia or stroke.

We recorded patients’ demographics and risk factors including age, gender, past history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, smoking and drinking. Hypertension, hyperlipidemia and diabetes mellitus were identified as previous diagnosis, or on current treatment. Smoking history was determined for each patient including was the patient a current smoker, past smoker, or had never smoked. Current and past smokers were both considered to have positive smoking history. Drinking history was defined as past reported alcohol consumption.

MRI protocol

All subjects underwent multi-model MRI by 3.0 T MR (GE Healthcare, United States) scanner using an 8-channel brain phased array coil, including 3 D-T1, T2, T2 FLAIR and SWI sequences. In order to minimize head motion, foam pads were inserted into the space between the subject's head and the MRI head coil. Sagittal 3 D-T1: repetition time = 7.3 ms, echo time = 3.0 ms, flip angle = 8°, thickness = 1 mm, field of view = 25 cm × 25 cm, matrix = 250 × 250 pixels. Axial T2: repetition time = 2500 ms, echo time = 4 ms/100 ms, thickness = 4 mm, field of view =24 cm × 24 cm, matrix = 512 × 512 pixels. Axial T2 FLAIR sequence was used to evaluate the WMHs severity with the following parameters: repetition time = 8400 ms, echo time = 150 ms, FOV = 24 cm × 24 cm, matrix size =256 × 256, inversion time = 2100 ms, slice thickness = 4.0 mm with no gap (continuous) between slices, and in-plane spatial resolution of 0.4688 mm/pixel × 0.4688 mm/pixel. The whole brain was imaged. The SWI sequence was in an axial orientation parallel to the anterior commissure to posterior commissure line and covered the whole lateral ventricles, using a three-dimension multi-echo gradient-echo sequence with 11 equally spaced echoes: echo time = 4.5 ms [first echo], inter-echo spacing = 4.5 ms, repetition time = 34ms, FOV = 24 cm × 24 cm, matrix size = 416 × 384, flip angle = 20°, slice thickness = 2.0 mm with no gap between slices and in-plane spatial resolution of 0.4688 mm/pixel. Flow compensation was applied. Magnitude and phase images were acquired.

Measurement of DMVs

The raw data were transferred to a separate workstation (ADW4.4, GE), and we used a custom built program to reconstruct the magnitude and phase images. DMVs were assessed on SWI phase images. Five consecutive periventricular slices (10 mm thick) from the level of the ventricles immediately above the basal ganglia to the level where the ventricles immediately disappeared were analyzed. Six regions including frontal region, parietal region and occipital region (bilateral, respectively) were separated on the above five slices according to medullary venous anatomy, and the characteristics of the DMVs were then evaluated in each region, respectively. 16

As described in our previous study, we used the four-point score to evaluate DMVs 16 : Grade 0 - each vein was continuous and had homogeneous signal; Grade 1- each vein was continuous, but one or more than one vein had inhomogeneous signal; Grade 2 - one or more than one vein was not continuous, presented with spot-like hypointensity; Grade 3 - no observed vein was continuous. The final DMVs score is the sum of the six regions ranging from 0 to 18. The higher score reflects more severe disruption of DMVs. Two neurologists (Z.K. and Z.Y.), who were completely blinded to the subjects' clinical data, visually assessed the vascular changes. Inter and intra rater reliability metrics of DMVs were checked by 2 raters using 50 randomly selected scans and estimated by intraclass correlation coeficient analysis. Inter and intra rater reliability of DMVs evaluation showed excellent agreement (ICC = 0.940 & 0.967).

Evaluation of PVS

PVS in the basal ganglia (BG-PVS), the centrum semiovale (CSO-PVS) and the hippocampus (H-PVS) were evaluated on T2 sequences, respectively. The slice with the maximum PVS in the basal ganglia or the centrum semiovale were chose to evaluate the grade, respectively. We used the five-point score to evaluate unilateral BG-PVS and CSO-PVS 18 using the worse side if there was any asymmetry: Grade 0 - no perivascular space can be found; Grade 1 - 1-10 perivascular spaces; Grade 2 - 11–20 perivascular spaces; Grade 3 - 21–40 perivascular space; Grade 4 - >40 perivascular spaces. H-PVS were counted according to the method proposed by Adams and collaborators. 19 But we selected the slices where midbrain and parahippocampal gyrus were visible, and counted H-PVS manually in both hemispheres. The sum of the left and right H-PVS was divided into five grades based on quartiles and the grade was used later for statistical analysis. Inter and intra rater reliability metrics were checked by 2 raters (Z.K. and Z.Y.) using 50 randomly selected scans and estimated by Kappa test. Both raters were blinded to the others ratings. Inter and intra rater reliability of PVS showed excellent agreement (BG-PVS: Kappa = 0.925 & 0.963; CSO-PVS: Kappa = 0.944 & 0.972; H-PVS: Kappa = 0.915 & 0.943).

Measurement of WMHs

T2 FLAIR sequences were used to assess WMHs, which were analyzed by two neurologists (W.J. and L.Q.) who were blinded to the clinical data. Disagreements were resolved through consensus. The Fazekas visual grading scale 20 was used to evaluate WMHs. WMHs were divided into periventricular hyperintensities (PWMHs) and deep white matter hyperintensities (DWMHs). PWMHs were graded as absent (grade 0), cap (grade 1), smooth halo (grade 2), or irregular and extending into the subcortical white matter (grade 3), and DWMHs were graded as absent (grade 0), punctate foci (grade 1), early-confluent (grade 2), or confluent (grade 3).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed on SPSS software version 22.0 (IBM Corporation). All data were subject to Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests for normality. The variable BG-PVS, CSO-PVS and H-PVS were all evaluated based on the five-point score. One-way analysis of variance was used to compare age among groups of PVS of different grades. Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare DMVs and WMHs among groups of PVS of different grades. Correlations between PVS and binary variables such as past histories were assessed by Chi square test. Variables with a p < 0.05 in univariate regression analyses were included in the multivariate linear regression analysis. All analyses were performed blinded to the participant identifying information. Statistical significance was set at a P value of < 0.05.

Ethical considerations

All subjects had been given written informed consent prior to the study, and the protocols had been approved by Human Ethics Committee of the Second Afflicted Hospital of Zhejiang University. All clinical investigation has been conducted according to the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Patient characteristics

During the study period, 270 patients were included in analysis (132 female; mean age, 61.5 ± 9.9 years). Eight (3.0%), 137 (50.7%), 71 (26.3%), 38 (14.1%), 16 (5.9%) patients presented BG-PVS as grade 0, 1, 2, 3 and 4, while 7 (2.6%), 75 (27.8%), 87 (32.2%), 64 (23.7%), 37 (13.7%) patients had CSO-PVS as grade 0, 1, 2, 3 and 4, respectively. The quartiles of H-PVS were 4, 6 and 8. Therefore H-PVS were divided into five grades: Grade 0 - no perivascular space can be found; Grade 1-1–4 perivascular spaces; Grade 2 - 5–6 perivascular spaces; Grade 3 - 7–8 perivascular space; Grade 4 - >8 perivascular spaces. Four (1.5%), 73 (27.0%), 79 (29.3%), 49 (18.1%), 65 (24.1%) patients showed H-PVS as grade 0, 1, 2, 3 and 4. Mean DMVs and PWMH score was 7.2 ± 3.7 (4–9) and 1.9 ± 1.0 (1–3), respectively. Mean DWMH score was 1.8 ± 1.1 (1–3).

Univariate analysis of PVS on severity and location

Tables 1 to 3 showed the characteristics of patients with different severity of BG-PVS, CSO-PVS and H-PVS, respectively. The severity of BG-PVS, CSO-PVS and H-PVS was positively related to the increment of age (p = 0.001, p = 0.006, p < 0.001). The severity of both BG-PVS and H-PVS was positively related to DMVs score (p = 0.008, p = 0.041). DMVs scores in left occipital, right frontal and right parietal region were significantly associated with BG-PVS (p = 0.043, 0.013 and 0.018, respectively). DMVs scores in left and right occipital region were significantly associated with H-PVS (p = 0.008 and 0.040, respectively). Besides, patients with more severe BG-PVS had higher Fazekas scores in both periventricle and deep white matter (p < 0.001, p < 0.001) and higher frequency of hypertension (p = 0.008). Patients with more severe H-PVS had higher frequency of diabetes (p < 0.001). No significant differences were found between CSO-PVS and other factors (all p > 0.05). Besides, the correlation analysis showed that there was a significant positive correlation between the severity of BG-PVS and CSO-PVS (r = 0.234, p < 0.001). Figure 1 shows the representative images of the relationship between DMVs and the grade of BG-PVS.

Table 1.

Comparison of baseline characteristics among patients presenting BG-PVS with different severity.

| Grade 0 (n = 8) | Grade 1 (n = 137) | Grade 2 (n = 71) | Grade 3 (n = 38) | Grade 4 (n = 16) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Year) | 57.00 ± 7.05 | 59.77 ± 9.85 | 63.42 ± 9.87 | 61.82 ± 9.69 | 69.44 ± 7.21 | 0.001 |

| Female | 4 (50.0) | 64 (46.7) | 38 (53.5) | 15 (39.5) | 11 (68.8) | 0.314 |

| History of hypertension | 1 (12.5) | 84 (61.3) | 50 (70.4) | 29 (76.3) | 15 (93.8) | 0.001 |

| History of hyperlipidemia | 1 (12.5) | 39 (28.5) | 16 (22.5) | 6 (15.8) | 8 (50.0) | 0.075 |

| History of diabetes | 2 (25.0) | 30 (21.9) | 14 (19.7) | 7 (18.4) | 4 (25.0) | 0.972 |

| Smoking history | 2 (25.0) | 30 (21.9) | 20 (28.2) | 5 (13.2) | 2 (12.5) | 0.383 |

| Drinking history | 0 (0.0) | 35 (25.6) | 12 (16.9) | 8 (21.1) | 1 (6.3) | 0.153 |

| DMVs | 7 (6–8) | 6 (4–8) | 7 (6–10) | 8 (5–10) | 8 (6–10) | 0.008 |

| PWMHs | 3 (1–3) | 1 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 3 (2–3) | 3 (2–3) | < 0.001 |

| DWMHs | 3 (0–3) | 1 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 3 (2–3) | 3 (2–3) | < 0.001 |

BG-PVS: MRI-visible perivascular spaces in basal ganglia; DMVs: deep medullary veins; PWMHs: periventricular hyperintensities; DWMHs: deep white matter hyperintensities.

Table 2.

Comparison of characteristics among patients presenting CSO-PVS with different severity.

| Grade 0 (n = 7) | Grade 1 (n = 75) | Grade 2 (n = 87) | Grade 3 (n = 64) | Grade 4 (n = 37) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Year) | 50.43 ± 10.63 | 61.20 ± 9.75 | 61.29 ± 10.71 | 61.25 ± 9.00 | 65.22 ± 8.18 | 0.006 |

| Female | 3 (42.9) | 36 (48.0) | 43 (49.4) | 33 (51.6) | 17 (46.0) | 0.978 |

| History of hypertension | 2 (28.6) | 46 (61.3) | 60 (69.0) | 47 (73.4) | 24 (64.9) | 0.133 |

| History of hyperlipidemia | 3 (42.9) | 21 (28.0) | 22 (25.3) | 18 (28.1) | 6 (16.2) | 0.523 |

| History of diabetes | 1 (14.3) | 15 (20.0) | 24 (27.6) | 11 (17.2) | 6 (16.2) | 0.468 |

| Smoking history | 2 (28.6) | 20 (26.7) | 20 (23.0) | 12 (18.8) | 5 (13.5) | 0.540 |

| Drinking history | 1 (14.3) | 16 (21.3) | 23 (26.4) | 11 (17.2) | 5 (13.5) | 0.471 |

| DMVs | 6 (3–9) | 6 (5–10) | 6 (4–9) | 6 (5–8) | 6 (5–10) | 0.968 |

| PWMHs | 1 (0–3) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 0.684 |

| DWMHs | 2 (0–3) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 0.476 |

CSO-PVS: MRI-visible perivascular spaces in centrum semiovale; DMVs: deep medullary veins; PWMHs: periventricular hyperintensities; DWMHs: deep white matter hyperintensities.

Table 3.

Comparison of baseline characteristics among patients presenting H-PVS with different severity.

| Grade 0 (n = 4) | Grade 1 (n = 73) | Grade 2 (n = 79) | Grade 3 (n = 49) | Grade 4 (n = 65) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Year) | 64.00 ± 15.08 | 59.11 ± 8.06 | 59.18 ± 11.09 | 65.49 ± 9.36 | 63.89 ± 9.10 | <0.001 |

| Female | 2 (50.0) | 38 (52.1) | 37 (46.8) | 27 (55.1) | 28 (43.1) | 0.728 |

| History of hypertension | 3 (75.0) | 42 (57.5) | 49 (62.0) | 38 (77.6) | 47 (72.3) | 0.130 |

| History of hyperlipidemia | 2 (50.0) | 16 (21.9) | 17 (21.5) | 12 (24.5) | 23 (35.4) | 0.225 |

| History of diabetes | 3 (75.0) | 13 (17.8) | 10 (12.7) | 7 (14.3) | 24 (36.9) | <0.001 |

| Smoking history | 0 (0.0) | 16 (21.9) | 15 (19.0) | 13 (26.5) | 15 (23.1) | 0.706 |

| Drinking history | 1 (25.0) | 13 (17.8) | 14 (17.7) | 9 (18.4) | 19 (29.2) | 0.426 |

| DMVs | 8 (5–14) | 6 (3–8) | 6 (5–10) | 8 (5–10) | 6 (5–9) | 0.041 |

| PWMHs | 2 (0–3) | 1 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 0.060 |

| DWMHs | 2 (0–3) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 0.358 |

H-PVS: MRI-visible perivascular spaces in hippocampus; DMVs: deep medullary veins; PWMHs: periventricular hyperintensities; DWMHs: deep white matter hyperintensities.

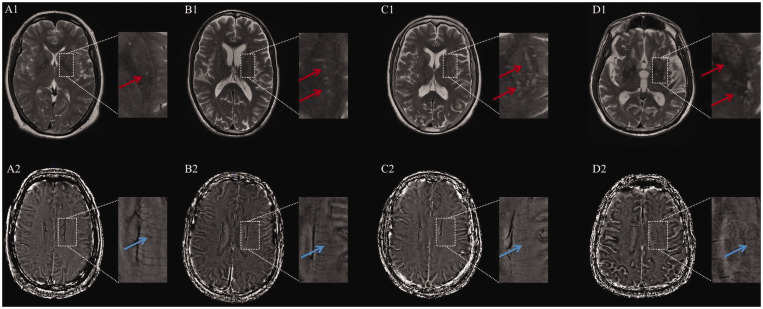

Figure 1.

Representative images showing the relationship between the grade of MRI-visible perivascular spaces in basal ganglia (BG-PVS) on T2-weighted image (A1-D1) and deep medullary veins (DMVs) on susceptibility weighted imaging-phase image (A2-D2). Red and blue arrows indicate BG-PVS and DMVs, respectively.

A 55 years-old female with BG-PVS of grade 1 had a DMVs score of 2 (A1-A2). A 65 years-old male had grade 2 BG-PVS with a DMVs score of 6 (B1-B2). A 73 years-old female had grade 3 BG-PVS with a DMVs score of 10 (C1-C2). A 80 years-old male had grade 4 BG-PVS with a DMVs score of 16 (D1-D2).

Multivariate regression analysis of PVS

The results of the multivariate regression analysis (Table 4) showed that high DMVs score was still an independent risk factor for more severe BG-PVS (β = 0.191, p = 0.002), after adjusting for confounding factors, while CSO-PVS and H-PVS showed no significant correlation with DMVs score after adjusting for confounding factors.

Table 4.

Multivariate linear regression analysis for the severity of PVS.

|

BG-PVS |

CSO-PVS |

H-PVS |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | p value | β | p value | β | p value | |

| Model 1 | ||||||

| DMVs | .169 | .006 | –.023 | .708 | .059 | .335 |

| Age | .223 | .000 | .153 | .016 | .226 | .000 |

| Sex | .043 | .476 | .033 | .592 | –.033 | .593 |

| TIV | –.003 | .959 | .052 | .412 | .077 | .219 |

| Model 2 | ||||||

| DMVs | .193 | .001 | –.020 | .753 | .071 | .251 |

| Age | .166 | .009 | .144 | .029 | .198 | .002 |

| Sex | .039 | .518 | .033 | .600 | –.035 | .567 |

| TIV | –.004 | .943 | .052 | .414 | .076 | .221 |

| History of hypertension | .196 | .002 | .029 | .661 | .096 | .137 |

| Model 3 | ||||||

| DMVs | .191 | .002 | –.022 | .725 | .074 | .228 |

| Age | .171 | .007 | .152 | .022 | .186 | .005 |

| Sex | .039 | .512 | .034 | .592 | –.036 | .554 |

| TIV | .001 | .991 | .059 | .355 | .065 | .297 |

| History of hypertension | .199 | .002 | .033 | .617 | .090 | .163 |

| History of diabetes | –.043 | .477 | –.062 | .328 | .093 | .133 |

BG-PVS: MRI-visible perivascular spaces in basal ganglia; CSO-PVS: MRI-visible perivascular spaces in centrum semiovale; H-PVS: MRI-visible perivascular spaces in hippocampus; DMVs: deep medullary veins; TIV: total intracranial volume.

Discussion

In the current study, we found that patients with more severe BG-PVS and H-PVS had higher DMVs scores but the severity of CSO-PVS was not associated with DMVs score. And after adjusting for confounding factors, no significant correlation was found between H-PVS and DMVs score. This suggested that venous disruption may be involved in the pathogenesis of BG-PVS, while deep medullary venous disruption is not associated with CSO-PVS. It should be noted that, in our study, the effect of DMVs on BG-PVS was independent of age and hypertension, which were taken for granted to be responsible for the changes of venous disruption.

Perivascular spaces have been proved to serve as the fundamental structure of the glymphatic (glial-lymphatic) pathway in the brain. This pathway subserves the flow of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) into the brain along perivascular spaces around arterioles and thence into the brain interstitium to exchange with interstitial fluid (ISF). The pathway then directs ISF towards perivascular spaces around venules, ultimately clearing solutes into meningeal and cervical lymphatic system. PVS have been regarded as a sign of glymphatic fluid stasis. 21 The decreased visibility of DMVs on SWI may reflect venous collagenosis, which could lead to venous wall thickening, stenosis, occlusion. 6 It has been demonstrated that venous insufficiency could increase static pulse pressure, leading to increased perivenular edema. 6 , 22 The drainage of glymphatic pathway in the perivenular spaces is subsequently blocked, resulting in the decrease of glymphatic clearance and retention of fluid in the perivascular spaces which encourages the occurrence of PVS.

Besides, high DMVs score may indicate the disruption of blood brain barrier (BBB). 2 In pathological conditions of increased BBB permeability, T cells may enter the brain and encounter activated antigen presenting cells, 23 which are strategically localized in perivascular spaces. 24 Antigen presenting cells can induce proliferation and differentiation of encephalitogenic T cells, which release pro-inflammatory cytokines. 25 This can lead to inflammatory response which may in turn trigger the exacerbation of PVS.

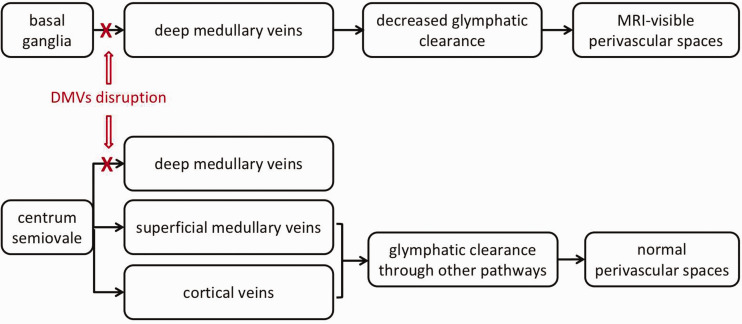

Interestingly, we found that venous disruption was related to the presence of BG-PVS, rather than CSO-PVS. According to previous literature, BG-PVS were considered to be related with hypertension, 10 , 11 , 14 while CSO-PVS were mainly related to cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA). 15 , 26 Pathological and immunochemical studies of CAA indicated that amyloid-β accumulated more frequently around cortical vessels, but less frequently seen in basal ganglia, thalamus, cerebellum, white matter and brainstem. 27 However, our present study only focused on DMVs which were localized in deep white matter, but didn't investigate superficial medullary veins and cortical veins. Further studies focusing on the interaction between superficial medullary veins and cortical veins and PVS are needed. Notably, the basal ganglia is drained by DMVs only, while the centrum semiovale can be drained by cortical veins and superficial medullary veins additionally. 28 , 29 , 30 This makes it possible that glymphatic system in the centrum semiovale could still maintain functional integrity under the circumstance of DMVs disruption, leading to the relatively normal size perivascular spaces in the centrum semiovale, as shown in Figure 2. This discrepancy might further lend support to the involvement of venous disruption in the pathogenesis of PVS.

Figure 2.

Schematic illustration for the potential mechanism of MRI-visible perivascular spaces in basal ganglia but not centrum semiovale. MRI-visible perivascular spaces (PVS) have been regarded as a sign of glymphatic fluid stasis. Cerebrospinal fluid enters the brain along perivascular spaces around arterioles, exchanges with interstitial fluid, then directs towards perivascular spaces around venules, ultimately clearing solutes into meningeal and cervical lymphatic system. Venous insufficiency may block the drainage of glymphatic pathway in the perivenular spaces, resulting in the decrease of glymphatic clearance and retention of fluid in the perivascular spaces which encourages the occurrence of PVS. Basal ganglia is mainly drained by deep medullary veins (DMVs), while centrum semiovale can be drained by cortical veins and superficial medullary veins additionally. Thus under the circumstance of DMVs disruption, glymphatic system in centrum semiovale could still maintain functional integrity.

Consistent with previous studies, our finding again confirms the relationship between PVS and aging. In a large population-based sample of elderly individuals, Zhu et.al found that the severity of PVS were strongly associated with age in both basal ganglia and white matter. 10 Yao et.al also found that the severity of PVS increased with age regardless of cerebral area. 31 It has been indicated that glymphatic dysfunction gets more severe with aging, 32 which makes it reasonable that the number of PVS increases in consequence.

We found that BG-PVS were more frequent in patients with hypertension, which is also in line with previous studies. Study found that the proportion of hypertensive subjects increased with the degrees of PVS in basal ganglia. 10 Hypertension was proved to be associated with PVS severity in basal ganglia, independent of age. 33 The nearly vertical bifurcation angle of the perforating arteries in basal ganglia makes it vulnerable to the increased blood pressure. This situation may accelerate the progress of BBB disruption, and even the decreased glymphatic clearance. We assume that both of them are related to the development of BG-PVS.

Our results also indicated that H-PVS were more frequent in patients with diabetes. Diabetes could lead to microvascular damage, 34 inflammatory responses 35 and stagnation of glymphatic transport, 36 which may play an important role in the H-PVS.

There were some limitations in our study. First, it was a prospective cross-sectional study, which made it difficult to prove the causality of conclusions above. Follow-up studies are required to clarify the correlation between DMVs scores and PVS. Second, it was a single-center study, so that it may not represent the full spectrum of cSVD and selection bias existed. Future prospective studies in larger and multicenter cohorts are required to clarify our results. Third, since it is difficult to evaluate superficial medullary veins and cortical veins due to their variations, we only analyzed the drainage of DMVs and did not find their association with CSO-PVS. Thus to further investigate the aetiology of CSO-PVS, more information about venous disruption in other areas that drain the centrum semiovale is needed in future. Besides, we used semi-quantitative visual scales for evaluation. More precise methods are needed to confirm our findings as automated quantification of the MRI-markers of cerebral small vessel disease is now available for WMHs and more recently for PVS.

In summary, our study found that DMVs disruption was associated with MRI-visible perivascular spaces in basal ganglia independent of age and hypertension, indicating that venous insufficiency may be one of the important pathogenic mechanisms of MRI-visible perivascular spaces.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-jcb-10.1177_0271678X211038138 for MRI-visible perivascular spaces in basal ganglia but not centrum semiovale or hippocampus were related to deep medullary veins changes by Kemeng Zhang, Ying Zhou, Wenhua Zhang, Qingqing Li, Jianzhong Sun and Min Lou in Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism

Footnotes

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81971101), the Science Technology Department of Zhejiang Province (2018C04011) and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFC1301503).

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Authors’ contributions: Z.K. and Z.Y. drafted the manuscript, participated in study design and data collection, conducted the statistical analyses, analyzed, and interpreted the data. L.M. participated in study study design and data collection, data interpretation and made a major contribution in revising the manuscript. S.J., Z.W. and L.Q. participated in designing the MRI sequences, data collection and imaging analysis.

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Wardlaw JM, Benveniste H, Nedergaard M, et al.; colleagues from the Fondation Leducq Transatlantic Network of Excellence on the Role of the Perivascular Space in Cerebral Small Vessel Disease. Perivascular spaces in the brain: anatomy, physiology and pathology. Nat Rev Neurol 2020; 16: 137–153. [InsertedFromOnline [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown R, Benveniste H, Black SE, et al. Understanding the role of the perivascular space in cerebral small vessel disease. Cardiovasc Res 2018; 114: 1462–1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shi Y, Thrippleton MJ, Makin SD, et al. Cerebral blood flow in small vessel disease: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2016; 36: 1653–1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shaaban CE, Molad J. Cerebral small vessel disease: moving closer to hemodynamic function. Neurology 2020; 94: 909–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qiu C, Cotch MF, Sigurdsson S, et al. Cerebral microbleeds, retinopathy, and dementia: the AGES-Reykjavik study. Neurology 2010; 75: 2221–2228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Julia K, Fu-Qiang G, Raza N, et al. Collagenosis of the deep medullary veins: an underrecognized pathologic correlate of white matter hyperintensities and periventricular infarction? J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2017; 76: 299–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown WR, Moody DM, Challa VR, et al. Venous collagenosis and arteriolar tortuosity in leukoaraiosis. J Neurol Sci 2002; 203-204: 159–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rouhl RPW, Oostenbrugge RJV, Knottnerus ILH, et al. Virchow-Robin spaces relate to cerebral small vessel disease severity. J Neurol 2008; 255: 692–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doubal FN, Maclullich AMJ, Ferguson KJ, et al. Enlarged perivascular spaces on MRI are a feature of cerebral small vessel disease. Stroke 2010; 41: 450–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu YC, Tzourio C, Soumare A, et al. Severity of dilated Virchow-Robin spaces is associated with age, blood pressure, and MRI markers of small vessel disease: a population-based study. Stroke 2010; 41: 2483–2490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klarenbeek P, van Oostenbrugge RJ, Lodder J, et al. Higher ambulatory blood pressure relates to enlarged Virchow-Robin spaces in first-ever lacunar stroke patients. J Neurol 2013; 260: 115–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wardlaw JM, Smith C, Dichgans M, et al. Mechanisms of sporadic cerebral small vessel disease: insights from neuroimaging. Lancet Neurol 2013; 12: 483–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramirez J, Berezuk C, Mcneely AA, et al. Imaging the perivascular space as a potential biomarker of neurovascular and neurodegenerative diseases. Cell Mol Neurobiol 2016; 36: 289–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang C, Chen Q, Wang Y, et al.; Chinese IntraCranial AtheroSclerosis (CICAS) Study Group. Risk factors of dilated Virchow-Robin spaces are different in various brain regions. PLoS One 2014; 9: e105505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Banerjee G, Jang H, Kim HJ, et al. Total MRI small vessel disease burden correlates with cognitive performance, cortical atrophy, and network measures in a memory clinic population. J Alzheimers Dis 2018; 63: 1485–1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang R, Zhou Y, Yan S, et al. A brain region-based deep medullary veins visual score on susceptibility weighted imaging. Front Aging Neurosci 2017; 9: 269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang R, Li Q, Zhou Y, et al. The relationship between deep medullary veins score and the severity and distribution of intracranial microbleeds. Neuroimage Clin 2019; 23: 101830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Potter GM, Chappell FM, Morris Z, et al. Cerebral perivascular spaces visible on magnetic resonance imaging: development of a qualitative rating scale and its observer reliability. Cerebrovasc Dis 2015; 39: 224–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adams HH, Cavalieri M, Verhaaren BF, et al. Rating method for dilated Virchow-Robin spaces on magnetic resonance imaging. Stroke 2013; 44: 1732–1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fazekas F, Niederkorn K, Schmidt R, et al. White matter signal abnormalities in normal individuals: correlation with carotid ultrasonography, cerebral blood flow measurements, and cerebrovascular risk factors. Stroke 1988; 19: 1285–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mestre H, Kostrikov S, Mehta R, et al. Perivascular spaces, glymphatic dysfunction, and small vessel disease. Clin Sci (Lond) 2017; 131: 2257–2274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leblebisatan G, Yiş U, Doğan M, et al. Obstructive hydrocephalus resulting from cerebral venous thrombosis. J Pediatr Neurosci 2011; 6: 129–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Engelhardt B, Carare RO, Bechmann I, et al. Vascular, glial, and lymphatic immune gateways of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol 2016; 132: 317–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greter M, Heppner FL, Lemos MP, et al. Dendritic cells permit immune invasion of the CNS in an animal model of multiple sclerosis. Nat Med 2005; 11: 328–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kawakami N, Lassmann S, Li Z, et al. The activation status of neuroantigen-specific T cells in the target organ determines the clinical outcome of autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Exp Med 2004; 199: 185–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Charidimou A, Meegahage R, Fox Z, et al. Enlarged perivascular spaces as a marker of underlying arteriopathy in intracerebral haemorrhage: a multicentre MRI cohort study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2013; 84: 624–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Biffi A, Greenberg SM. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy: a systematic review. J Clin Neurol 2011; 7: 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang YP, Wolf BS. Veins of the white matter of the cerebral hemispheres (the medullary veins). Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med 1964; 92: 739–755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee C, Pennington MA, Kenney CM, et al. R evaluation of developmental venous anomalies: medullary venous anatomy of venous angiomas. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1996; 17: 61–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taoka T, Fukusumi A, Miyasaka T, et al. Structure of the medullary veins of the cerebral hemisphere and related disorders. Radiographics 2017; 37: 281–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yao M, Hervé D, Jouvent E, et al. Dilated perivascular spaces in small-vessel disease: a study in CADASIL. Cerebrovasc Dis 2014; 37: 155–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou Y, Cai JS, Zhang WH, et al. Impairment of the glymphatic pathway and putative meningeal lymphatic vessels in the aging human. Ann Neurol 2020; 87: 357–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hurford R, Charidimou A, Fox Z, et al. MRI-visible perivascular spaces: relationship to cognition and small vessel disease MRI markers in ischaemic stroke and TIA. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2014; 85: 522–525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prasad S, Sajja RK, Naik P, et al. Diabetes mellitus and blood-brain barrier dysfunction: an overview. J Pharmacovigil 2014; 2: 125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rouhl RP, Damoiseaux JG, Lodder J, et al. Vascular inflammation in cerebral small vessel disease. Neurobiol Aging 2012; 33: 1800–1806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang H, Fan X, Weiner M, et al. Distinctive disruption patterns of white matter tracts in Alzheimer's disease with full diffusion tensor characterization. Neurobiol Aging 2012; 33: 2029–2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-jcb-10.1177_0271678X211038138 for MRI-visible perivascular spaces in basal ganglia but not centrum semiovale or hippocampus were related to deep medullary veins changes by Kemeng Zhang, Ying Zhou, Wenhua Zhang, Qingqing Li, Jianzhong Sun and Min Lou in Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism