Abstract

Background: The frequency, pattern, and treatment of pediatric hand fractures are rarely reported. We sought to review our institution’s experience in the management of pediatric hand fractures. Methods: A retrospective review of children and adolescents (younger than 18 years) treated for hand fractures between January 1990 and June 2017 was preformed. Fractures were categorized into metacarpal, proximal/middle phalanx, distal phalanx, or intra-articular metacarpophalangeal (MCP)/proximal interphalangeal (PIP)/distal interphalangeal (DIP) fractures. Patients were categorized into 3 age groups (0-5, 6-11, and 12-17 years). Results: A total of 4356 patients were treated for hand fractures at a mean ± SD age of 12.2 ± 3.5 years. Most fractures occurred in patients aged 12 to 17 years (n = 2775, 64%), followed by patients aged 6 to 11 years (n = 1347, 31%). Only 234 (5%) fractures occurred in children younger than 5 years. Most fractures occurred in the proximal/middle phalanx (48%), followed by metacarpal (33%), distal phalangeal (12%), and intra-articular MCP/PIP/DIP joints (7%). Proximal/middle phalangeal fractures were the most common in all age groups. About 58% of intra-articular MCP/PIP/DIP fractures in patients aged between 0 and 5 years required open reduction ± fixation, and the remaining 42% fractures were amenable to closed reduction. In patients older than 5 years, about 70% of these fractures were amenable to closed reduction. All age groups included, most metacarpal (93%), proximal/middle phalangeal (92%), and distal phalangeal (86%) fractures were amenable to closed reduction alone. Conclusions: The frequency, pattern, and treatment of hand fractures vary among different age groups. Understanding the pattern of these fractures helps making the right diagnosis and guides choosing the appropriate treatment.

Keywords: hand fractures, pediatric, diagnosis, incidence, pattern, treatment, research and health outcomes

Introduction

The hand is the most common site of injury in the pediatric population and adolescents, and hand fractures represent one of the most frequent reasons for emergency department visit in these age groups.1-8 Due to physes and incomplete ossification of the carpus that may not appear in radiographs, identifying pediatric hand fractures might be challenging with a misdiagnosis rate of 8%.8,9 When accurately diagnosed and managed, these fractures have good outcomes; therefore, knowing the epidemiology, location, and required treatment of hand fractures in children and adolescents will be helpful to hand surgeons and primary care and emergency department providers who manage these conditions. The epidemiology of pediatric hand fractures differs between different populations because these injuries are related to the environment, as well as the local children’s sports practice. 9 The purpose of this study was to review the pattern, location, and treatment of pediatric hand fractures treated at a tertiary rural Midwest care center over a 27-year period.

Materials and Methods

After institutional review board approval, a retrospective review of children and adolescents (younger than 18 years) treated for hand fractures from January 1990 and June 2017 was performed. Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes were used to capture patients treated for hand fractures. Patients who had the CPT codes listed in Table 1 were included in our study. Patients who did not have the CPT codes (Table 1) for hand fractures in their chart were not captured, and therefore this was the exclusion criterion. Fractures were categorized into: (1) metacarpal; (2) proximal/middle phalanx; (3) distal phalanx; and (4) intra-articular metacarpophalangeal (MCP)/proximal interphalangeal (PIP)/distal interphalangeal (DIP) fractures. Patients were divided into 3 age groups (0-5, 6-11, and 12-17 years). Descriptive statistics were used.

Table 1.

CPT Codes for Hand and Finger Fractures.

|

CPT codes for hand fractures

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Procedure | Metacarpal | Phalangeal shaft, proximal/middle | Intra-articular, MCP/PIP/DIP | Distal phalanx |

| Closed treatment without manipulation | 26600 | 26720 | 26740 | 26750 |

| Closed treatment with manipulation | 26605 | 26725 | 26742 | 26755 |

| Closed reduction with external fixation | 26607 | 26727 | 26746 | 26756 |

| Percutaneous pin fixation | 26608 | 26727 | 26746 | 26756 |

| Open reduction with or without fixation | 26615 | 26735 | 26746 | 26765 |

Note. CPT = Current Procedural Terminology; MCP = metacarpophalangeal; PIP = proximal interphalangeal; DIP = distal interphalangeal.

Results

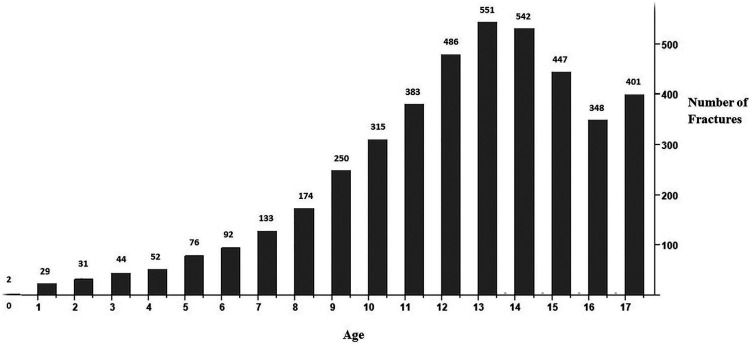

During the study period, 4356 patients (71% male) were treated for hand fractures at a mean ± SD age of 12.2 ± 3.5 years. Most of the fractures occurred in patients aged 12 to 17 years (n = 2775, 64%), followed by patients aged 6 to 11 years (n = 1347, 31%). Only 234 (5%) fractures occurred in children aged 5 years and younger. Distribution of hand fractures by age is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Distribution of hand fractures by age.

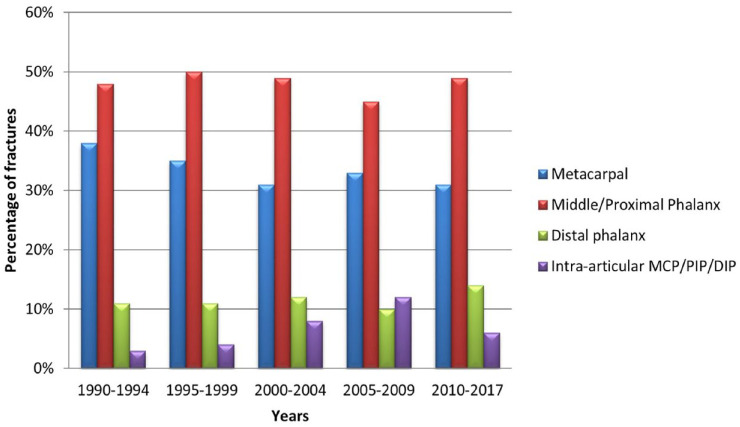

Middle and proximal phalanx fractures were the most common in all years, followed by metacarpal fractures. Distal phalanx fractures were more common than intra-articular MCP/PIP/DIP fractures in all years, except in the period 2005-2009 during which the incidence of intra-articular MCP/PIP/DIP fractures (14%) was slightly higher than the incidence of distal phalanx fractures (10%). The percentage of hand fractures over the years is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Percentage of different hand fractures over periods of years.

Note. MCP = metacarpophalangeal; PIP = proximal interphalangeal; DIP = distal interphalangeal.

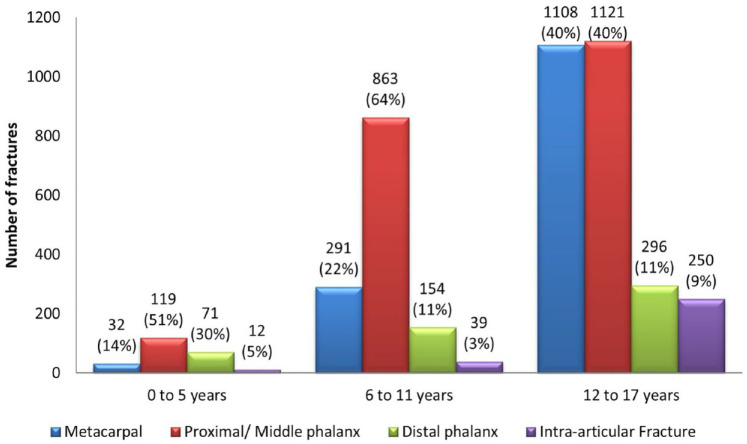

The frequency of hand fractures increased gradually with age, reaching a peak incidence in patients aged 12 to 14 years. Considering all age groups, most fractures occurred in the proximal/middle phalanx (n = 2103, 48%), followed by metacarpal (n = 1431, 33%), distal phalangeal (n = 521, 12%), and intra-articular MCP/PIP/DIP joints (n = 301, 7%). The anatomical site of hand fractures by age group is presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Distribution of hand fractures by anatomical site and age group.

Considering all fractures, most of them (90%) were amenable to closed treatment. The open reduction internal fixation (ORIF) was the technique chosen in 7% of the fractures. Percutaneous pinning (PP) was used only in 3% of the cases. Fracture management divided by age group and anatomical site is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Fracture Management Divided by Age Group and Anatomical Site.

| Fracture management | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Subgroup and anatomical localization | Closed reduction | ORIF | PP |

| Subgroup 0-5 years | |||

| Extra-articular (222 fractures) | |||

| Metacarpal (32) | 28 (87%) | 3 (10%) | 1 (3%) |

| Proximal/Middle phalanx (119) | 94 (79%) | 13 (11%) | 12 (10%) |

| Distal phalanx (71) | 65 (92%) | 5 (7%) | 1 (1%) |

| Intra-articular fracture (12 fractures) | |||

| MCP/PIP/DIP (12) | 5 (42%) | 7 (58%) | — |

| Subgroup 6-11 years | |||

| Extra-articular (1308 fractures) | |||

| Metacarpal (291) | 284 (98%) | 3 (1%) | 4 (1%) |

| Proximal/Middle phalanx (863) | 824 (95%) | 18 (2%) | 21 (3%) |

| Distal phalanx (154) | 130 (84%) | 20 (13%) | 4 (3%) |

| Intra-articular fracture (39 fractures) | |||

| MCP/PIP/DIP (39) | 28 (72%) | 11 (28%) | — |

| Subgroup 12-17 years | |||

| Extra-articular (2525 fractures) | |||

| Metacarpal (1108) | 1014 (92%) | 59 (5%) | 35 (3%) |

| Proximal/ Middle phalanx (1121) | 1031 (92%) | 56 (5%) | 34 (3%) |

| Distal phalanx (296) | 242 (82%) | 35 (12%) | 19 (6%) |

| Intra-articular fracture (250 fractures) | |||

| MCP/PIP/DIP (250) | 185 (74%) | 65 (26%) | — |

| Total fractures: 4356 | 3930 (90%) | 295 (7%) | 131 (3%) |

Note. ORIF: open reduction internal fixation; PP: percutaneous pinning; MCP = metacarpophalangeal; PIP = proximal interphalangeal; DIP = distal interphalangeal.

Patients 0 to 5 Years

In patients aged between 0 and 5 years, a total of 234 fractures were identified. Proximal/middle phalanx (n = 119, 51%) was the most common, followed by distal phalangeal (n = 71, 30%), metacarpal (n = 32, 14%), and intra-articular MCP/PIP/DIP (n = 12, 5%) fractures.

Proximal/middle phalanx fractures were treated with closed reduction in 94 (79%), ORIF in 13 (11%), and PP in 12 (10%) patients. Distal phalangeal fractures were amenable to closed treatment in 65 patients (92%), and the remaining required either ORIF (n = 5, 7%) or PP (n = 1, 1%). Metacarpal fractures were treated with closed reduction in 28 (88%), ORIF in 3 (9%), and PP in 1 (3%) patients. Intra-articular MCP/PIP/DIP fractures required ORIF in 7 patients (58%), whereas 5 patients (42%) were treated with closed reduction only.

Patients 6 to 11 Years

In patients aged between 6 and 11 years, the frequency of fractures identified was proximal/middle phalanx (n = 863, 64%), followed by metacarpal (n = 291, 22%), distal phalanx (n = 154, 11%), and intra-articular MCP/PIP/DIP (n = 39, 3%).

Most of the proximal/middle phalanx fractures were treated with closed reduction in 824 (95%), PP in 21, (3%) and ORIF in 18 (2%) patients. Metacarpal fractures were treated with closed reduction in 284 (98%), PP in 4 (1%), and ORIF in 3 (1%) patients. Distal phalangeal fractures were amenable to closed treatment in 130 (84%), ORIF in 20 (13%), and PP in 4 (3%) patients. Intra-articular MCP/PIP/DIP fractures were managed with closed treatment in 28 (72%) and ORIF in 11 (28%) patients.

Patients 12 to 17 Years

In patients aged between 12 and 17 years, proximal/middle phalanx fractures (n = 1121, 40%) had a similar frequency to metacarpal fractures (n = 1108, 40%). Distal phalanx fractures occurred in 296 (11%) patients, whereas intra-articular MCP/PIP/DIP fractures occurred in 250 (9%) patients.

Most of the proximal/middle phalanx fractures were treated with closed reduction in 1031 (92%), ORIF in 56 (5%), and PP in 34 (3%) patients. Metacarpal fractures were treated with closed reduction in 1014 (92%), ORIF in 59 (5%), and PP in 35 (3%) patients. Distal phalangeal fractures were amenable to closed treatment in 242 (82%), ORIF in 35 (11%), and PP in 19 (7%) patients. Intra-articular MCP/PIP/DIP fractures required closed reduction in 185 patients (74%), whereas 65 patients (26%) were treated with ORIF.

Overview

In patients aged 0 to 11 years, proximal/middle phalanx fractures were the most common, whereas in patients aged 12 to 17 years, proximal/middle phalanx fractures were as common as metacarpal fractures. Intra-articular MCP/PIP/DIP fractures remained the least common type of fractures in all age groups.

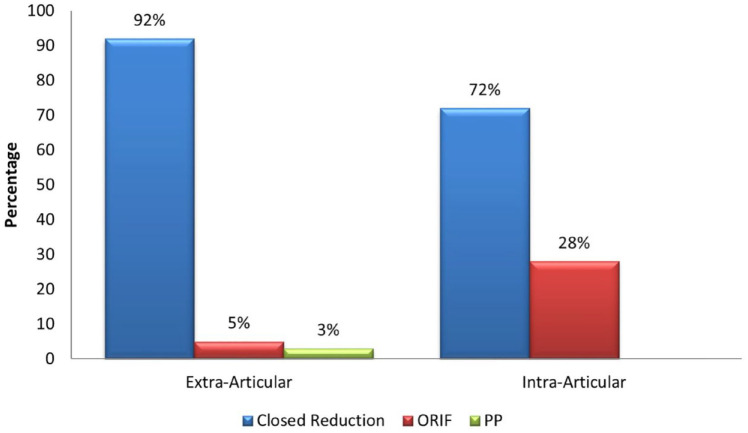

A total of 4055 (93%) extra-articular fractures were identified. In this subgroup, the management was closed reduction in 3712 (92%), ORIF in 212 (5%), and PP in 131 (3%) patients.

The remaining 301 (7%) fractures were intra-articular. In this subgroup, the management was closed reduction in 218 (72%) and ORIF in 83 (28%) patients. The management of extra-articular versus intra-articular fractures is represented in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Management of extra-articular and intra-articular hand fractures.

Note. ORIF = open reduction internal fixation; PP = percutaneous pinning.

Discussion

Based on our findings, the pattern of hand fractures differs among different children and adolescent age groups. In our study, proximal/middle phalanx fractures were the most common (48%); similarly, Chew and Chong 9 reported a prevalence of 49% of proximal phalanx fractures in children, and Lempesis et al 10 reported a prevalence of 60% of phalangeal fractures in the same subset of patients. Proximal/middle phalanx fractures without intra-articular extension are the most common fractures in children 11 years and younger. Beyond age 11, proximal/middle phalanx and metacarpal fractures occur at a similar frequency. Previous authors reported that the older the child, the more proximal fracture that was sustained.9,11 Chew and Chong 9 identified that the median age of children sustaining fractures of the distal phalanges was 9 years, the proximal phalanges was 12 years, and the metacarpals was 15 years. The number of all kinds of fractures increases gradually with age until it reaches a peak incidence at ages 12 to 14, during which most adolescents engage in sports activities. A higher prevalence of hand fractures in older children was reported in previous studies.9,11,12 However, despite the overall increase in all hand fractures, the proportion of each fracture differs between different age groups.

Pediatric hand fractures rarely require operative management. 13 Despite the variation of the proportion of hand fractures in different age groups, most extra-articular fractures are amenable to closed reduction in all age groups. The intra-articular extension of fractures is associated with decreased probability of closed reduction management alone, and open treatment is often required. As previously reported, intra-articular fractures are more likely to need ORIF. 14 In such cases, about one-third of the fractures in patients older than 5 years will require open treatment ± fixation, whereas in patients younger than 5 years, over half of the patients will require open treatment ± fixation.

There are certain limitations of our study that we acknowledge. The retrospective collection of data was dependent on the accuracy and completeness of the medical record and CPT codes. Radiographs of all patients were not available for review. Other limitation includes the lack of a comparison cohort and practice changes over time. However, given the large sample, our results help define the pattern and treatment of different hand fractures across a wide age range.

Conclusion

Pediatric hand fractures vary among different age groups, including their frequency, pattern, and treatment. Identifying pediatric hand fractures might be challenging and presents a considerable misdiagnosis rate; knowing the pattern of the fractures presented in this study might be helpful to hand surgeons and primary care and emergency department providers to anticipate the most likely patterns of fractures they will face in their clinical practice.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: This manuscript was presented at the American Association for Hand Surgery (AAHS) Meeting in 2018, Phoenix, AZ, USA.

Ethical Approval: This study was approved by our institutional review board.

Statement of Human and Animal Rights: All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. This article does not contain any studies with animal subjects.

Statement of Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Lucas Kreutz-Rodrigues  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2954-0628

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2954-0628

Karim Bakri  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8860-9798

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8860-9798

References

- 1. Barton NJ. Fractures of the phalanges of the hand in children. Hand. 1979;11(2):134-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hastings H, 2nd, Simmons BP. Hand fractures in children. A statistical analysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1984(188):120-130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Naranje SM, Erali RA, Warner WC, Jr, et al. Epidemiology of pediatric fractures presenting to Emergency Departments in the United States. J Pediatr Orthop. 2016;36(4):e45-e48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Al-Jasser FS, Mandil AM, Al-Nafissi AM, et al. Epidemiology of pediatric hand fractures presenting to a university hospital in Central Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2015;36(5):587-592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Antabak A, Barisic B, Andabak M, et al. [Hand fractures in children — causes and mechanisms of injury]. Lijec Vjesn. 2015;137(9-10):306-310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Liu EH, Alqahtani S, Alsaaran RN, et al. A prospective study of pediatric hand fractures and review of the literature. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2014;30(5):299-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mahabir RC, Kazemi AR, Cannon WG, et al. Pediatric hand fractures: a review. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2001;17(3):153-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nellans KW, Chung KC. Pediatric hand fractures. Hand Clin. 2013;29(4):569-578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chew EM, Chong AK. Hand fractures in children: epidemiology and misdiagnosis in a tertiary referral hospital. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37(8):1684-1688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lempesis V, Rosengren BE, Landin L, et al. Hand fracture epidemiology and etiology in children-time trends in Malmo, Sweden, during six decades. J Orthop Surg Res. 2019;14(1):213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rajesh A, Basu AK, Vaidhyanath R, et al. Hand fractures: a study of their site and type in childhood. Clin Radiol. 2001;56(8):667-669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Landin LA. Fracture patterns in children. Analysis of 8,682 fractures with special reference to incidence, etiology and secular changes in a Swedish urban population 1950-1979. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl. 1983;202:1-109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Young K, Greenwood A, MacQuillan A, et al. Paediatric hand fractures. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2013;38(8):898-902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kamath JB, Harshvardhan Naik DM, Bansal A. Current concepts in managing fractures of metacarpal and phalangess. Indian J Plast Surg. 2011;44(2):203-211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]