Abstract

In all, 30% to 90% of prostate cancer patients undergoing radical prostatectomy (RP) recover their erectile capacity. No effective post RP erectile rehabilitation program exists to date. The aim of this exploratory qualitative study is to explore the needs of these patients and to develop a patient education program (PEP) which meets these needs. Interviews were carried out by a socio-anthropologist with prostate cancer patients treated by RP within the 6 previous months. The needs and expectations identified led to the choice of a logical model of change for the construction of the PEP. Nineteen patients were included in the study; 17 of them were living with a partner. Two categories of patients appeared during the interviews: informed patients resigned to lose their sexuality and patients misinformed about the consequences of the surgery. The tailored program was built on the Health Belief Model and provides six individual sessions, including one with the partner, to meet the needs identified. This study designed the first program to target comprehensively the overall sexuality of the patient and his partner, and not only erection issues. To demonstrate the effectiveness of this program, a controlled, multicentric clinical trial is currently ongoing.

Keywords: prostate cancer, erectile dysfunction, sexual function, erectile rehabilitation, patient education

Introduction

Prostate cancer is the second most frequent solid tumor in men worldwide with an incidence of 1.28 million new cases in 2018 (Bray et al., 2018). Ninety percent of the patients are diagnosed in the early stages of the disease with rates of survival 15 years of 82% (Siegel et al., 2020). Radical prostatectomy (RP) is one of the two recommended active treatments in this indication (the other one being radiotherapy), which is undertaken after a trade-off between toxicity and prevention of disease progression (Vickers et al., 2012). Even if progress were made in surgical treatment procedures(Walsh, 2007), the rate of erectile dysfunction (ED) post RP is high: it varies between 30% and 90% depending on the study (Alemozaffar et al., 2011; Donovan et al., 2016; Tal et al., 2009). It is the element that impacts the quality of life the most after RP (Mulhall, 2009). The time needed for the recovery of an erection after nerve sparring prostatectomy is variable and can be more than 2 years (Rozet et al., 2005). Other frequent undesirable effects associated with RP are reduction in the length of the penis, pain, and orgasmic incontinence. Men also suffer from a lack of self-confidence, a decrease in libido, and satisfaction of their sexual intercourse (Briganti et al., 2011; Nelson et al., 2010). The link between ED and depression has been clearly established: Their association is considered a bidirectional relationship in which the two conditions reinforce each other in a downward spiral. (Mulhall, 2009). It has also been reported that the quality of sexual life of the partners following RP strongly decreased and that this degradation of quality of life increased over time (Ramsey et al., 2013).

The principal treatments used in first intention to support or cause erections are Type 5 inhibitors of phosphodiesterate (PDE5I), intra-cavernous injections (IICs) of vaso-active agent and vacuum (Salonia et al., 2017). No long-term effectiveness of these treatments used alone has been demonstrated for the moment (Liu et al., 2017). Studies have sought to report the interest of erectile rehabilitation post RP for the most rapid recovery of a functional erection (allowing penetration; Terrier et al., 2014; Toussi et al., 2021). The sooner those rehabilitation programs start, the most effective the program is on sexual dysfunction (Schoentgen et al., 2021; Tang et al., 2020) The objectives of this rehabilitation programs are to limit the installation of intra-cavernous fibrosis, to oxygenate the cavernous bodies, to limit the retraction of the penis and the loss of size. But those rehabilitation programs, even though broadly disseminated, are predominantly based on pharmacology and concentrate on the erection as if it was the only factor for men’s successful sexuality (Philippou et al., 2018). It is probably too reductive not to consider the globality of a man’s sexuality to improve his whole sexual life quality. Sexuality for men encompasses indeed erections, but among others, libido, desire, orgasm, satisfaction, sense of masculine completeness. It is also a two-way exchange implying intimacy, relationship, interaction with one’s partner, communication ability. and eventually mental well-being (Montorsi et al., 2010; Mooney & Mooney, 2011). All these dimensions must be taken into account if sexual health is to be achieved in these patients (Chung & Brock, 2013; Salonia et al., 2017). The actual state-of-the-art recommendations in post RP ED management reports that (a) administration of PDE5 is vaccum erection devices and intracorporeal injections are equally effective treatments; (b) whatever treatment is undertaken, it is better to initiate it as close as possible from surgery (Bratu et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2017; Schoentgen et al., 2021); (c) in case of refractory ED, penile prosthesis implant is an effective and satisfactory alternative (Lima et al., 2020); and (d) yet no proper algorithm or specific regimen is established as optimal (Salonia et al., 2017). Lately, few trials assessed more comprehensive and multimodal rehabilitation programs, including psychological intervention and sexual counseling (Matthew et al., 2018; Osadchiy et al., 2020), but those are scares and yet to be disseminate in the common practice, whereas patients’ needs stay considerable and unsatisfied (Giuliano et al., 2008).

Patient education provides patients with the abilities and skills which empowers them to live with their disease, in an optimal way (World Health Organization, 1998). Patients become their own actors and no longer need to repeatedly refer to a health professional. Patients acquire experiential knowledge and capacity, the ability to manage one’s condition by oneself, and to react to a new situation. This is about patient’s empowerment. Patient education programs (PEPs) are effective where the objective goes beyond the recovery of a physical function. In the cancer patient post RP situation, the objective is to get a sustainable and comprehensive improvement in the quality of the sexual life of the patient: the complexity of knowledge, skills, abilities, and inter-relational adaptations to be implemented by the patient require this kind of holistic patient-centered approach. The development of cancer PEPs, as recommended by the National Cancer Institute (NCI; CPEN Guidelines draft_Oct7 2013.indd—CPENStandardsofPractice.Nov14.pdf) comprises three phases: (a) identification of educational needs, (b) development of the PEP, and (c) assessment of the program. This project aims at elaborating a PEP on the improvement of sexuality, according to these recommendations.

To cover Phases 1 and 2, the aim of this study was twofold: (a) to establish a collective educational diagnosis, by exploring the beliefs, the representations, and the knowledge of the patients about their disease and sexual difficulties, their experiences, and their expectations in terms of the management of their sexuality; (b) to build a tailored PEP, based on international recommendations.

Method

Qualitative Study

A qualitative exploratory study ran from April to September 2018. Qualitative approach is a completely adapted method to identify patients’ educational needs in the prospect of developing a tailored PEP. This method allows to grasp all the complexity of the life of people suffering from ED post RP. It allows to generate in-depth accounts from their way of life and what they are lacking, their difficulties. It allows to identify the educational needs of those patients according to their reported issues. It is highly recommended to construct PEPs according to the context (Skivington et al., 2021) and tailored to the patients’ needs (CPEN Guidelines Guidelines draft_Oct7 2013.indd—CPENStandardsofPractice.Nov14.pdf). Only qualitative research allows to fulfill those two objectives with completeness and flexibility. The study was approved by the ethics committee of Angers (CPP Ouest II, N°: 2017-A02749-44). Written informed consent was collected and filed for each participant. The qualitative study is reported as recommended in the COREQ guidelines.

Sample

A prospective sampling selection has been performed: eligible patients were prostate cancer patients who had undergone an RP operation. Only patients who had had the operation in the past 6 months were recruited, to have a better understanding of their early difficulties and expectations. Exclusion criteria were any difficulties with language and comprehension. The patients were recruited at the time of their consultation in the urology ward of the University Hospital of Lyon. Patients were screened by the urologist according to their concordance with the selection criteria. Patients received information from the urologist, who asked them to participate in the interview to speak about the impact of their treatment (face-to-face approach). Patients were included consecutively, depending on their eligibility, on a voluntary basis.

There are no existing recommendation concerning sample size in qualitative studies. The necessary number of participants is that which allows data saturation. Saturation is defined as the point where no new or relevant information is obtained by doing further interviews and recent studies suggest that saturation is generally reached with 12 to 13 interviews. In the study, the interviews were continued until data saturation was reached, meaning that no new findings were added. The researcher validates this step through a cumulative analysis: after each interview and coding of the new raw data, the researcher resumes his codification. The iterative process continues until a plausible and coherent organization, ensuring the intelligibility of the discourse, makes it possible to conclude that the various codified meanings are saturated.

Interviews

The interviews were done in French by a female socio-anthropologist, trained in qualitative interviews, especially in the field of cancer. There was no prior relationship between the interviewer and the research team (two urologists, three methodologists, two sociology researchers, and one educational science researcher). Interviews took place at participants’ home. Interviews were fully recorded on a digital audio recorder. Each interview was transcribed in verbatim and anonymized.

The approach taken by the socio-anthropologist was a constructivist approach. To ensure the trustworthiness of results, it is the wisdom, abilities, expertise, and experiment of the interviewer as an anthropologist that allowed her to overtake her context (young women, for example), and the context of those being interviewed (older men, for example), to comprehend their truth. It allows her to avoid her characteristics, views, and beliefs to influence the interactions they have with the participants: She embraced a situated stance during the interviews (Kuper et al., 2008).

The interview guide was made of open-ended questions. Questions explored (a) the illness and the surgical operation impact on virility, on sexuality; (b) the information patients received about sexual “rehabilitation”; (c) the role of the partner (if any) concerning support during the illness, as well as for sexual rehabilitation; (d) sociodemographic and socioeconomic contextual data.

Analysis

The interpretations of the material collected by the researcher followed the constructivist approach: they included her physical, psychological, social contexts, as well as individuals’ (respondents) contexts, to comprehend their truth. The methodological orientation chosen for this study was the content analysis. It is a research method that aims at attaining a condensed and broad description of a phenomenon. The outcome of the analysis is concepts or categories describing the phenomenon (Krippendorff, 2018). Transcripts were read, and line-by-line analysis was conducted to extract significant statements from the interviews, following established guidelines for a content analysis (Krippendorff, 2018). These statements were used to generate specific codes, and each transcript was then coded using this content coding scheme. The themes emerging from the first interviews helped to refine the interview guide used for the next set of interviews. Data analysis was performed simultaneously and continually with the data collection to identify data saturation. The information was categorized into main themes of representations and needs. Thematic content analysis is a reduction of the complexity of the discourse. This method was chosen to identify a finite and operational list of educational objectives. This is achieved through the identification of themes. The collection of codes was made by C.H. and J.K. to assure a comprehensive interpretation and a grouping of code elements into themes. A.D., with her expertise of research in this domain, checked the process and results for accuracy. Participant did not provide feedback on the findings.

Translation Into Educational Needs and Program Construction

The program was developed by a multidisciplinary team composed of a specialist in education science, a sociologist, an urologist, and a methodologist. To construct adequately the program, a theoretical model of change (a psychological model that allows the understanding of health behaviors. It defines the key factors that influence individuals’ health behaviors. It articulates how change happens in the wider context) was chosen by the team, according to the results of the qualitative study. Within this change model, educational objectives for each educational need were defined and placed. The Martin and Savary method of educational diagnosis was used to translate representations into educational needs (Martin et al., 1999). This method guides the reporting of one or more adapted educational objectives leading from an unsatisfactory situation to the expected situation, taking into account existing resources. Martin and Savary’s educational diagnosis model describes how to move from a standard response to an adapted patient education intervention. Therefore, this method can be applied to all situations of program construction while adapting to each situation and context.

Results

Qualitative Study

Sample

Thirty patients, meeting the selection criteria, were proposed the study by their urologist. Nineteen patients were included in the study; the median age was 61.6 years (42–70 years). The interview took place on average 3.2 months after RP (Table 1). Overall, 90% (17/19) of the participants were living in a relationship, 63% (12/19) were retired. The refusal reasons were for one half that they were too tired to conduct an interview, and the other half dropped out because they did not succeed in finding spare time to meet the interviewer. All participants were met at home. All interviews were performed in a one-to-one session.

Table 1.

Patients’ Characteristics.

| Variables N = 19 | N(%) or median (minimum–maximum) |

|---|---|

| Age in years | 61, 6 (42–70) |

| Time since prostate surgery | |

| 6 weeks | 7 (37%) |

| 3 months | 4 (21%) |

| 4–5 months | 6 (32%) |

| 6 months | 2 (10%) |

| In a relationship | |

| Yes | 17 (90%) |

| No | 2 (10%) |

| Occupation | |

| Active | 7 (37%) |

| Retired | 12 (63%) |

Comprehension of Information Received in Consultation, Concerning Sexuality

The two greatest factors limiting comprehension, as mentioned by participants, were embarrassment and the rapidity of the consultation. Being given by the urologist the opportunity to speak freely was much appreciated by the various participants; however, the presence of a resident or other member of staff present during the consultation intimidated the men and led them to elude certain questions. Some participants expressed the desire to have access to reliable website references to read up about their illness and treatment, as well as access to written documentation, reiterating information that had been given during the consultation.

Knowledge Concerning the Conservation of the Neurovascular Bundle

Comprehension of what had been carried out during the surgical operation was really diverse, depending on the participant. Concerning the status of the participants related to the neurovascular bundle sparing at the time of surgical operation, four participants did not know their situation.

Incontinence

This is the side effect that worried the participants the most, more than the intervention itself, or sexually related problems. In daily life, incontinence appeared to be much more a socially shameful issue than sexual problems, which were considered as being more of an intimate issue.

One feels belittled, things are moving forward but it takes a long time for them to do so.

The absence of urinary “leaks” was considered by the participants as a necessary precondition for the resumption of sexual intercourse. Succeeding in this first stage of urinary retention was likely to increase confidence in sexual recovery.

The fact that I did not suffer from incontinence reconciled me with the rest!

Sexuality

Two categories of participants appeared during the interviews. One profile of participants, consisting of informed patients, who deliberately decided to resign themselves to no longer having a sexual life (resigned patients). The second profile of participants consisted in misinformed patients, about the consequences of the surgery (misinformed patients). Those patients are being subjected to the degradation of their sexuality.

Resigned Patients

For these patients, they considered that the loss of their sexuality was secondary, compared with their survival. So, they often gave less importance to the sexual dimension of their illness.

Sexuality? I had crossed that off my list . . ., my concern was primarily with not having metastases, therefore not having a life threat.

I live very well without sexual relationships, I do not expect anything in particular. The essence is to be in good health.

So sexual problems . . . I knew that they were going to exist, and in my head it was clear: all good things come to an end, we have to accept that. I take it very well.

For these patients, sacrificing sexuality was significant enough for it to be a hindrance to the seeking of a solution for their sexual recovery.

When I decided to have the operation, I went through the mourning process of my sexuality. But as I now see that there are nevertheless solutions, I almost find it difficult getting out of my mourning state . . . thus I am here to get over my mourning!!

Misinformed Patients

The doctors seemed to be rather optimistic overall, and the patients understood that there was a broad panel of solutions available and this allowed them to put trust in the fact that they could regain an erection.

He told me that in 70% of the cases, patients regained an erection . . . And he told me that if I did not immediately regain an erection, there were special products for that.

The professor tells me: we will tackle erectile recovery (in 1 month). “Hmm.” . . I say . . .“but, will it work??” He says “Oh, no problem!!” We have a kind of pen-injection and there are creams and gels, Viagra-type pills. . . No problem! Just like before! Without ejaculation, but not a problem. He is confident.

But in reality, the patients did not understand the necessity of the “rehabilitation” dimension of the issue, which would imply that the methods used did not give total satisfaction. The account of successive failures or unexpected situations disarmed some men, who then largely lost confidence.

Even if it was probably evoked during the consultation, information concerning the absence of sperm was sometimes occulted by the participants who did not understand what was happening and which added to their demotivation.

I was shocked: I no longer have sperm, I no longer ejaculate and how can I put it? I feel hard done by . . . I don’t feel like having sex anymore . . .

For these “confused” patients, the absence of regular sexual intercourse was difficult to become accustomed to. The loss of sexual spontaneity due to the intake of IDPE5 or to the administration of an IIC changed the way they considered sexuality.

The different obstacles which impact initiating sexual rehabilitation were as follows:

No Links Perceived Between Erectile Rehabilitation and the Diminution of Intra-Cavernous Fibrosis

The participants did not understand the dimension of post RP, erectile rehabilitation. Only two participants established a link between the absence of erection and the risk of developing intra-cavernous fibrosis. For many, erectile rehabilitation meant the resumption of sexual activity. However, some considered that their sexuality was a thing of the past and were thus not motivated and not ready to resume their sex life.

The Cost of the Type 5 Phosphodiesterase Inhibitors

IPDE5 is not reimbursed in France, and its high cost has been mentioned several times by participants. Some did not respect the dosage of the treatment, to save money: daily treatment became irregular, the participants postponed beginning the treatment while waiting to be in a context where sexual activity would be possible.

The Unclearly Defined Role of the Sexual Partners

The role of the partners is tricky. Some men mentioned their concerns at not being able “to satisfy their partners” because of EDs. In the framework of rehabilitation, the partners’ contribution could be advantageous. But for some participants, the role of the partner learning all the technical dimensions which are required is difficult to set. This role needs to first be explained in detail to the partners and negotiated by the urologists.

The Acceptability of the IIC

Most participants expressed a very strong reservation toward the injections, all of them had an initially negative standpoint before the first injection.

Four out of 19 said they could not (would not) adhere to an injected treatment. The thought of giving themselves an injection was unimaginable because of needle phobia.

Personally, I fear injections, but as long as they are in an auto-injector, you do not see the needle and that’s great. All apprehension disappears. (M15)

The difficulty is also in the identification and management of the dosage: several mentioned the problem of prolonged or painful erections.

A demonstration of how to give an injection was much appreciated as it demystified the gesture.

Change in Self-Image

Many said they felt tired and vulnerable. Certain participants also expressed how their virility had been impacted and were concerned with no longer being able to fulfill their function as husband on a sexual level.

Our virility takes a blow. It is hard psychologically. . .

Program Construction

Once the obstacles and incentives are identified, a wise choice concerning the intervention methods is to define appropriately the contents and articulations of the educational messages. These methods are based on theoretical logical models of change.

From the results of the qualitative study, it was judged relevant to choose the Health Belief Model (HBM) as a conceptual framework. Indeed, this model states that to adhere to or to maintain healthy behavior, there are four interdependent postulates that the patients must accept:

To be convinced that he is afflicted by a disease (in this case, sexual dysfunction). Investigation found that sexuality is not the priority of certain patients. The patients do not measure “the emergency” of the situation or may minimize the problem. Sometimes they may even go through the mourning process of their “previous” life and seem to accept the loss of their sexual capacity as the price to pay for their cure. This may be considered as a fatality. The program has to leverage this very first state.

To consider that the disease (in this case, sexual dysfunction) and its consequences may be serious for them. In the investigation, only certain patients made a direct connection between the consequences of the sexual dysfunction and the relationship with the partner and the degree of acceptance of this one. Most patients are still in a state of mourning, giving priority to their survival. Consequences of the therapeutic gesture are minimized. This is the second step to work on in the program.

To believe that following the treatment will be beneficial for them. The study reveals that the role of the existing and proposed treatments and care management is not necessarily understood and that the beneficial effects of care management are not necessarily accepted. If the attempts made do not give encouraging results right from the start, the patients lose confidence. This confidence and skills must be developed by the program.

To believe that the benefits of the care management outweigh the side effects as well as the psychological, social, and financial constraints generated by this care management. The study reveals that not many patients are motivated by the idea of having to administrate IICs and that for many it may simply be impossible (needle phobia). The cost of certain treatments may also constitute an obstacle. The side effects are not necessarily outweighed by the beneficial aspects. Despite the treatment, obtaining an erection may be difficult and may be subject to conditions that are considered to be unfavorable. This balance must be reversed.

The program was thus built upon the foundations and conceptual framework of the HBM, as it best matches the structure of the situation that the patients are faced with. It develops knowledge, skills, and psychosocial skills.

The specific educational objectives, identified and formulated through this prism, thanks to the diagram of Martin and Savary, are the following:

Identifying the mechanisms of erection before the intervention (“normal” situation);

Explaining the impact of the intervention on these mechanisms (motivational session);

Detailing the advantages of rapidly resuming sexual activity;

Explaining the role of the proposed treatments;

Explaining the advantages as well as the disadvantages of these treatments;

Detailing the possible means to limiting these disadvantages;

Mastering all the skills related to technical gestures;

Knowing who and how to contact in case help is needed (communication skills);

Identifying the obstacles and incentives to resuming, with the help of treatments, the patients’ sexual activity. The presence of the partner is proposed for this objective (self-efficacy and communication skills).

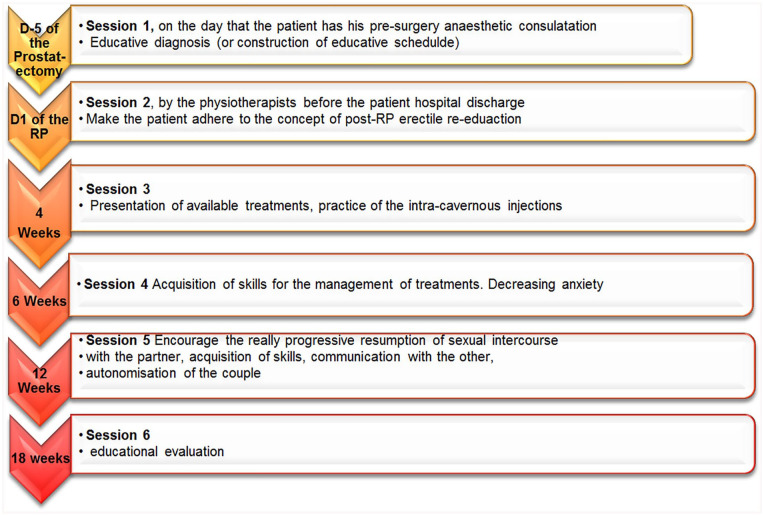

The program was built around six sessions (Figure 1). All sessions will be individual as the qualitative study highlighted that all patients experienced a major obstacle related to collective discussion (with other patients) on sexuality. The qualitative study also stressed the importance of involving the sexual partner in the educative process: a session with the patient and partner was thus organized. Finally, this study underlined the benefits of involving physiotherapists in the educational team. Those professionals, through their expertise, are particularly appropriate in the transmission of the technical skills and techniques that need to be acquired. Physiotherapists have already the function in the early postsurgery—independently of the PEP and in current practice—of proposing systematically urinary continence rehabilitation. The extension of this function to educate the patient in sexual rehabilitation makes sense in this context.

Figure 1.

Patient Education Program

Note. Figure 1 describes all consecutive sessions of the patient education program offered to prostate cancer patients undergoing radical prostatectomy, reporting educational content and schedule.

The patient education team, according to its usual organization, will regularly come back to the patient to offer him, if needed, consolidation educational sessions throughout the patient’s care. This need will be expressed by the patient according to the level of autonomy acquired by him, as a result of the patient education.

Discussion

The results of this study underline the low level of preparation of the patients for the sexual consequences of RP. Their representations with respect to post RP were not adapted; they have little knowledge on the importance of rapid rehabilitation, their skills in implementing the latter was practically nonexistent, and thus their needs were identified as considerable in this field.

A PEP has been built to address all these needs, specifically. This program’s construction follows all the quality guidelines of program development, to ensure it will fulfill all its objectives and is adapted to the population targeted.

Two categories of patients are here to be taken care of: “resigned” and “misinformed.” For the first, it is assumed that the motivational session of the program would be of importance to change their grasp of the problem: both improvements of survival and sexuality are absolutely compatible. Concerning the “misinformed,” the provision of comprehensive knowledge and skills made by the program should reveal and fulfill the unknown needs.

Still, for both groups, there is a common pathway: they are confronted, postoperation, with an individual ED, but it is the sexuality of the couple, on the whole, that is impacted. Many studies have attempted to study the effectiveness of medical treatments on erections, while ignoring the essence of accompaniment and education relating to sex life in its broadest sense. Erection is not the only concern of the patients: the absence of ejaculation, incontinence, the decrease in the size of the penis, or the feeling of “no longer being a man” (Bokhour et al., 2001; Fergus et al., 2002) are elements that hugely impact the sexual quality of life of the patients. Nelson et al. (2010) reported that, even after having recovered an erectile score equivalent to the preoperative erectile score, sexual satisfaction decreased systematically. Schover et al. (2002) reported 85% of 1,236 post RP men complaining about ED, 45% having a decrease in libido and 65% lacking orgasm (Schover et al., 2002). Donovan et al. (2016) confirmed the existence of these pervasive side effects, and in the long run. Walker et al. evaluated the contribution “of workshops on intimate communication for the couple” designed to help the couples in their sexuality following the RP. They noted that the relations of the couples improved considerably, but changes related to sexual satisfaction in the men were not significant (Walker et al., 2017). It is thus probable that reaching the sexual state enjoyed before treatment is impossible. This reality, illustrated by our study, has many implications on the management of these patients, in particular on the information given before the operation, by the urologist. It is necessary to anticipate patients’ expectations and to step very lightly so as to avoid disappointments.

Certain patients choose RP to benefit from the conservation of the neurovascular strips and consequently to preserve their sexuality. This is particularly true after robotically assisted RP, where expectations in terms of functional results are higher. Schroeck et al. (2008, 2012) reported that those patients had many more regrets and disappointments than patients undergoing open surgery, because they had greater hopes in terms of functional results.

We believe that a PEP will be able to fill these gaps in knowledge, skills, and psychosocial skills, in terms of the consequences of RP on sexuality and will be able to give the patients all the necessary skills for the resumption of sexual activity while avoiding false beliefs and hopes.

While following the methodology of construction of a PEP recommended by the NCI, we ensure, a priori, the quality of this program: The educational objectives were built within an adapted conceptual framework, based on an exploratory study on the patients targeted. The specificity of this population was taken into account: The sessions respect the intimacy of the patient and one of the sessions aims at including, as much as possible, the partner. The couples will thus be able “to renegotiate” their sexuality after cancer and to fight against the phallocentric model of sexuality (Ussher et al., 2013). According to Ussher, “the resistance to the imperative requirement of coitus should be a fundamental aspect of the information and support provided by the health professionals.”

This study is one of the few to develop a nonmedication approach to rehabilitation for ED after RP. The majority of the literature on the subject focuses on screening for ED and treatment with drugs. It is difficult to find and discuss studies that specifically address the construction of a behavioral intervention in this setting. Toussi et al. (2021) recently succeeded in demonstrating the effectiveness of a nonmedical device not only on penile length but also on sexual intercourse and overall sexual satisfaction. We hope that this type of study will open up perspectives on the management of these patients.

Our study also presents certain limitations: the principal one being that patients were recruited in only one center and all underwent an operation by assisted laparoscopy robot. Second, we did not take into account their preoperational sexuality, which inevitably has an impact on how surgery is experienced, but which also enabled us to avoid any further selection bias. Third, the characteristics of the socio-anthropologist (age, gender, social class, posture) may have interacted with the respondents and their discourses in two ways: when they were interviewed and when she interpreted the verbatims. This is why it was mandatory to have a trained socio-anthropologist, with experience in cancer patients’ interviews, so that she could adopt a proper situated stance during the interviews and a proper analytical methodology. The similitude with the literature on needs expressed by patients confirms that her characteristics did not “bias” the results of the qualitative study. Fourth, post RP incontinence is not directly targeted inside our PEP. Yet it is indirectly addressed, either through the organizational choices of the program or through the psychosocial skills developed under this program. Indeed, this PEP recommends that the first education sessions be led by a physiotherapist. However, the physiotherapist is already present in the urology department and already assists patients in continence rehabilitation. There is thus a perfect continuity between the management of continence and sexual dysfunction. In addition, the program teaches patients to identify obstacles to their sexuality and to seek medical help when necessary. This applies to the 15% of patients with persistent incontinence who require medical treatment for it (Salomon et al., 2015). Finally, 18 weeks may be considered too short for an intervention of sexual rehabilitation. However, patient education is not an intervention requiring repeated practices or continuous training with an experienced professional. PEP is about empowering the patient, meaning giving him the ability to continue his rehabilitation by himself. Patient education usually sets patients goals of adherence to treatment, independent management of side effects, and unexpected situations. It allows the patient to become independent of the health system. The effects of the PEP are thus supposed to remain sustainable over time, beyond those 18 first weeks.

Conclusion

The results of the qualitative study lead to build a tailored PEP aiming at improving the sexuality of patients after RP, in accordance with the current quality standards of patient education in cancer, making it possible to meet patients’ expectations. To demonstrate the effectiveness in real life of this program on the sexuality of patients, it is currently assessed in a controlled, multicentric clinical trial.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thanks Susan Guillaumond (activenglish) and Philippe Bourmaud, for translation and editing services.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: J.E.T., A. Bo., F.C., A.R. and V.R. contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by C.H., J.K., A. Ba., and A.D. The first draft of the manuscript was written by J.E.T and A. Bo., and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics Approval: The study was approved by the ethics committee of Angers (CPP Ouest II, N°: 2017-A02749-44).

Consent to Participate: Written informed consent was collected and filed for each participant.

Consent for Publication: All authors gave full consent for publication of this manuscript.

ORCID iD: Aurelie Bourmaud  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2228-6471

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2228-6471

Availability of Data and Material: All data are available upon reasonable request.

References

- Alemozaffar M., Regan M. M., Cooperberg M. R., Wei J. T., Michalski J. M., Sandler H. M., Hembroff L., Sadetsky N., Saigal C. S., Litwin M. S., Klein E., Kibel A. S., Hamstra D. A., Pisters L. L., Kuban D. A., Kaplan I. D., Wood D. P., Ciezki J., Dunn R. L., . . . Sanda M. G. (2011). Prediction of erectile function following treatment for prostate cancer. Journal of the American Medical Association, 306(11), 1205–1214. 10.1001/jama.2011.1333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bokhour B. G., Clark J. A., Inui T. S., Silliman R. A., Talcott J. A. (2001). Sexuality after treatment for early prostate cancer: Exploring the meanings of “erectile dysfunction.” Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(10), 649–655. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.00832.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bratu O., Oprea I., Marcu D., Spinu D., Niculae A., Geavlete B., Mischianu D. (2017). Erectile dysfunction post-radical prostatectomy—A challenge for both patient and physician. Journal of Medicine and Life, 10(1), 13–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray F., Ferlay J., Soerjomataram I., Siegel R. L., Torre L. A., Jemal A. (2018). Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 68(6), 394–424. 10.3322/caac.21492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briganti A., Gallina A., Suardi N., Capitanio U., Tutolo M., Bianchi M., Salonia A., Colombo R., Di Girolamo V., Martinez-Salamanca J. I., Guazzoni G., Rigatti P., Montorsi F. (2011). What is the definition of a satisfactory erectile function after bilateral nerve sparing radical prostatectomy? The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 8(4), 1210–1217. 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02179.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung E., Brock G. (2013). Sexual rehabilitation and cancer survivorship: A state of art review of current literature and management strategies in male sexual dysfunction among prostate cancer survivors. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 10(Suppl. 1), 102–111. 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.03005.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CPEN Guidelines draft_Oct7 2013.indd—CPENStandardsofPractice.Nov14.pdf. (n.d.). http://www.cancerpatienteducation.org/docs/CPEN/Educator%20Resources/CPENStandardsofPractice.Nov14.pdf

- Donovan J. L., Hamdy F. C., Lane J. A., Mason M., Metcalfe C., Walsh E., Blazeby J. M., Peters T. J., Holding P., Bonnington S., Lennon T., Bradshaw L., Cooper D., Herbert P., Howson J., Jones A., Lyons N., Salter E., Thompson P., & ProtecT Study Group*. (2016). Patient-reported outcomes after monitoring, surgery, or radiotherapy for prostate cancer. The New England Journal of Medicine, 375(15), 1425–1437. 10.1056/NEJMoa1606221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergus K. D., Gray R. E., Fitch M. I. (2002). Sexual dysfunction and the preservation of manhood: Experiences of men with prostate cancer. Journal of Health Psychology, 7(3), 303–316. 10.1177/1359105302007003223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuliano F., Amar E., Chevallier D., Montaigne O., Joubert J.-M., Chartier-Kastler E. (2008). How urologists manage erectile dysfunction after radical prostatectomy: A national survey (REPAIR) by the French urological association. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 5(2), 448–457. 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00670.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorff K. (2018). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Kuper A., Reeves S., Levinson W. (2008). An introduction to reading and appraising qualitative research. British Medical Journal, 337, Article a288. 10.1136/bmj.a288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima T. F. N., Bitran J., Frech F. S., Ramasamy R. (2020). Prevalence of post-prostatectomy erectile dysfunction and a review of the recommended therapeutic modalities. International Journal of Impotence Research, 33, 401–409. 10.1038/s41443-020-00374-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C., Lopez D. S., Chen M., Wang R. (2017). Penile rehabilitation therapy following radical prostatectomy: A meta-analysis. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 14(12), 1496–1503. 10.1016/j.jsxm.2017.09.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin J.-P., Savary É., & Centre académique de formation continue (Nantes). (1999). Formateur d’adultes: Se professionnaliser, exercer au quotidien [Adult educator: Becoming professional, daily practice]. EVO, Chronique sociale [Google Scholar]

- Matthew A., Lutzky-Cohen N., Jamnicky L., Currie K., Gentile A., Mina D. S., Fleshner N., Finelli A., Hamilton R., Kulkarni G., Jewett M., Zlotta A., Trachtenberg J., Yang Z., Elterman D. (2018). The prostate cancer rehabilitation clinic: A biopsychosocial clinic for sexual dysfunction after radical prostatectomy. Current Oncology (Toronto, Ont.), 25(6), 393–402. 10.3747/co.25.4111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montorsi F., Adaikan G., Becher E., Giuliano F., Khoury S., Lue T. F., Sharlip I., Althof S. E., Andersson K.-E., Brock G., Broderick G., Burnett A., Buvat J., Dean J., Donatucci C., Eardley I., Fugl-Meyer K. S., Goldstein I., Hackett G., . . . Wasserman M. (2010). Summary of the recommendations on sexual dysfunctions in men. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 7(11), 3572–3588. 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02062.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mooney C. D., Mooney A. N. (2011). Trop proches pour être bien: Les effets de la prostatectomie radicale sur l’intimité: L’expérience d’un couple de professionnels [Too close to be well: The effects of radical prostatectomy on intimacy: The experience of a professional couple]. Canadian Family Physician, 57(2), e37–e38. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulhall J. P. (2009). Defining and reporting erectile function outcomes after radical prostatectomy: Challenges and misconceptions. The Journal of Urology, 181(2), 462–471. 10.1016/j.juro.2008.10.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson C. J., Deveci S., Stasi J., Scardino P. T., Mulhall J. P. (2010). Sexual bother following radical prostatectomyjsm. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 7(1 Pt. 1), 129–135. 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01546.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osadchiy V., Eleswarapu S. V., Mills S. A., Pollard M. E., Reiter R. E., Mills J. N. (2020). Efficacy of a preprostatectomy multi-modal penile rehabilitation regimen on recovery of postoperative erectile function. International Journal of Impotence Research, 32(3), 323–328. 10.1038/s41443-019-0187-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philippou Y. A., Jung J. H., Steggall M. J., O’Driscoll S. T., Bakker C. J., Bodie J. A., Dahm P. (2018). Penile rehabilitation for postprostatectomy erectile dysfunction. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 10, Article CD012414. 10.1002/14651858.CD012414.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey S. D., Zeliadt S. B., Blough D. K., Moinpour C. M., Hall I. J., Smith J. L., Ekwueme D. U., Fedorenko C. R., Fairweather M. E., Koepl L. M., Thompson I. M., Keane T. E., Penson D. F. (2013). Impact of prostate cancer on sexual relationships: A longitudinal perspective on intimate partners’ experiences. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 10(12), 3135–3143. 10.1111/jsm.12295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozet F., Galiano M., Cathelineau X., Barret E., Cathala N., Vallancien G. (2005). Extraperitoneal laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: A prospective evaluation of 600 cases. The Journal of Urology, 174(3), 908–911. 10.1097/01.ju.0000169260.42845.c9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomon L., Droupy S., Yiou R., Soulié M. (2015). Functional results and treatment of functional dysfunctions after radical prostatectomy. Progres En Urologie: Journal De l’Association Francaise D’urologie Et De La Societe Francaise D’urologie, 25(15), 1028–1066. 10.1016/j.purol.2015.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salonia A., Adaikan G., Buvat J., Carrier S., El-Meliegy A., Hatzimouratidis K., McCullough A., Morgentaler A., Torres L. O., Khera M. (2017). Sexual rehabilitation after treatment for prostate cancer-part 2: Recommendations from the fourth international consultation for sexual medicine (ICSM 2015). The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 14(3), 297–315. 10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.11.324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoentgen N., Califano G., Manfredi C., Romero-Otero J., Chun F. K. H., Ouzaid I., Hermieu J.-F., Xylinas E., Verze P. (2021). Is it worth starting sexual rehabilitation before radical prostatectomy? Results from a systematic review of the literature. Frontiers in Surgery, 8, Article 648345. 10.3389/fsurg.2021.648345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schover L. R., Fouladi R. T., Warneke C. L., Neese L., Klein E. A., Zippe C., Kupelian P. A. (2002). Defining sexual outcomes after treatment for localized prostate carcinoma. Cancer, 95(8), 1773–1785. 10.1002/cncr.10848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeck F. R., Krupski T. L., Stewart S. B., Bañez L. L., Gerber L., Albala D. M., Moul J. W. (2012). Pretreatment expectations of patients undergoing robotic assisted laparoscopic or open retropubic radical prostatectomy. The Journal of Urology, 187(3), 894–898. 10.1016/j.juro.2011.10.135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeck F. R., Krupski T. L., Sun L., Albala D. M., Price M. M., Polascik T. J., Robertson C. N., Tewari A. K., Moul J. W. (2008). Satisfaction and regret after open retropubic or robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy. European Urology, 54(4), 785–793. 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.06.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel R. L., Miller K. D., Jemal A. (2020). Cancer statistics, 2020. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 70(1), 7–30. 10.3322/caac.21590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skivington K., Matthews L., Simpson S. A., Craig P., Baird J., Blazeby J. M., Boyd K. A., Craig N., French D. P., McIntosh E., Petticrew M., Rycroft-Malone J., White M., Moore L. (2021). A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: Update of Medical Research Council guidance. British Medical Journal, 374, Article n2061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tal R., Alphs H. H., Krebs P., Nelson C. J., Mulhall J. P. (2009). Erectile function recovery rate after radical prostatectomy: A meta-analysis. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 6(9), 2538–2546. 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01351.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang C. Y., Turczyniak M., Sayner A., Haines K., Butzkueven S., O’Connell H. E. (2020). Adopting a collaborative approach in developing a prehabilitation program for patients with prostate cancer utilising experience-based co-design methodology. Supportive Care in Cancer, 28(11), 5195–5202. 10.1007/s00520-020-05341-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terrier J.-E., Ferretti L., Journel N. M., Ben-Naoum K., Graziana J.-P., Huyghe E., Marcelli F., Methorst C., Montaigne O., Savareux L., Faix A. (2014). Should we recommend an erectile rehabilitation after radical prostatectomy? Systematic review of the literature by the Sexual Medicine Committee of the French Urology Association. Progres En Urologie: Journal De l’Association Francaise D’urologie Et De La Societe Francaise D’urologie, 24(16), 1043–1049. 10.1016/j.purol.2014.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toussi A., Ziegelmann M., Yang D., Manka M., Frank I., Boorjian S. A., Tollefson M., Köhler T., Trost L. (2021). Efficacy of a novel penile traction device in improving penile length and erectile function post prostatectomy: Results from a single-center randomized, controlled trial. The Journal of Urology, 206(2), 416–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ussher J. M., Perz J., Gilbert E., Wong W. K. T., Hobbs K. (2013). Renegotiating sex and intimacy after cancer: Resisting the coital imperative. Cancer Nursing, 36(6), 454–462. 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3182759e21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vickers A., Bennette C., Steineck G., Adami H.-O., Johansson J.-E., Bill-Axelson A., Palmgren J., Garmo H., Holmberg L. (2012). Individualized estimation of the benefit of radical prostatectomy from the Scandinavian Prostate Cancer Group randomized trial. European Urology, 62(2), 204–209. 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.04.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker L. M., King N., Kwasny Z., Robinson J. W. (2017). Intimacy after prostate cancer: A brief couples’ workshop is associated with improvements in relationship satisfaction. Psycho-Oncology, 26(9), 1336–1346. 10.1002/pon.4147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh P. C. (2007). The discovery of the cavernous nerves and development of nerve sparing radical retropubic prostatectomy. The Journal of Urology, 177(5), 1632–1635. 10.1016/j.juro.2007.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (1998). Therapeutic patient education: Continuing education programmes for health care providers in the field of prevention of chronic diseases: Report of a WHO working group (No. EUR/ICP/QCPH 01 01 03 Rev. 2). [Google Scholar]