Keywords: arterial end-tidal carbon dioxide difference, blood gases, HFpEF, physiological dead space, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure

Abstract

Patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) exhibit cardiopulmonary abnormalities that could affect the predictability of exercise from the Jones corrected partial pressure of end-tidal CO2 (PJCO2) equation (PJCO2 = 5.5 + 0.9 × − 2.1 × VT). Since the dead space to tidal volume (VD/VT) calculation also includes measurements, estimates of VD/VT from PJCO2 may also be affected. Because using noninvasive estimates of and VD/VT could save patient discomfort, time, and cost, we examined whether partial pressure of end-tidal CO2 () and PJCO2 can be used to estimate and VD/VT in 13 patients with HFpEF. was measured from expired gases measured simultaneously with radial arterial blood gases at rest, constant-load (20 W), and peak exercise. VD/VT[art] was calculated using the Enghoff modification of the Bohr equation, and estimates of VD/VT were calculated using (VD/VT[ET]) and PJCO2 (VD/VT[J]) in place of . was similar to at rest (−1.46 ± 2.63, P = 0.112) and peak exercise (0.66 ± 2.56, P = 0.392), but overestimated at 20 W (−2.09 ± 2.55, P = 0.020). PJCO2 was similar to at rest (−1.29 ± 2.57, P = 0.119) and 20 W (−1.06 ± 2.29, P = 0.154), but underestimated at peak exercise (1.90 ± 2.13, P = 0.009). VD/VT[ET] was similar to VD/VT[art] at rest (−0.01 ± 0.03, P = 0.127) and peak exercise (0.01 ± 0.04, P = 0.210), but overestimated VD/VT[art] at 20 W (−0.02 ± 0.03, P = 0.025). Although VD/VT[J] was similar to VD/VT[art] at rest (−0.01 ± 0.03, P = 0.156) and 20 W (−0.01 ± 0.03, P = 0.133), VD/VT[J] underestimated VD/VT[art] at peak exercise (0.03 ± 0.04, P = 0.013). Exercise and VD/VT[ET] provides better estimates of and VD/VT[art] than PJCO2 and VD/VT[J] does at peak exercise. Thus, estimates of and VD/VT should only be used if sampling arterial blood during CPET is not feasible.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY provides a better estimate of than PJCO2 at peak exercise, and VD/VT[ET] provides a better estimate of VD/VT[art] than VD/VT[J] at peak exercise. Although we reported significant correlations, we did not find an identity between and estimates of , nor did we find an identity between VD/VT[art] and estimates of VD/VT[art]. Thus, caution should be taken and estimates of and VD/VT should only be used if sampling arterial blood during CPET is not feasible.

INTRODUCTION

During a cardiopulmonary exercise test (CPET), measuring arterial blood gases provides useful information about gas exchange efficiency. To avoid the risks associated with arterial puncture, efforts have been made to estimate arterial CO2 () noninvasively. One method uses end-tidal CO2 () in place of (1), and a second method estimates from a prediction equation developed by Jones et al. (1) that utilizes and tidal volume (VT)

| (1) |

where VT is in liters.

Studies in younger individuals have shown that is a good index of at rest, and PJCO2 corrects for the overestimation of by during exercise (1–6). In contrast, we (4) and others (1) have shown that in older individuals PJCO2 significantly underestimates during exercise, whereas provides a better estimate of . These contrasting findings are likely explained by age-related changes in pulmonary function that increase ventilation-perfusion (V/Q) mismatching (7), which alters the relationship between and .

The relationship between and is also altered by cardiopulmonary abnormalities (8). In particular, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) is associated with many cardiopulmonary abnormalities including pulmonary congestion (9, 10), elevated cardiac filling pressures and pulmonary hypertension (11, 12), impaired pulmonary diffusing capacity (13, 14), impaired pulmonary vascular recruitment/distension (14–16), and right ventricle-pulmonary artery uncoupling (17–19). These cardiopulmonary abnormalities could increase V/Q mismatching and thus reduce the predictability of from PJCO2 in patients with HFpEF, particularly during exercise when cardiopulmonary abnormalities are potentially exacerbated and the magnitude of V/Q mismatching is likely to worsen. In addition to V/Q mismatch, peripheral extraction of oxygen delivered to exercising muscle is impaired with patients with HFpEF (20). Impaired extraction of oxygen at the exercising muscle would reduce the normal elevation in mixed venous Pco2, which may also alter the relationship between and during exercise in patients with HFpEF.

An additional variable important in studies of gas exchange is the determination of the magnitude of V/Q mismatch, which can be estimated by calculating the physiologic dead space to tidal volume (VD/VT) ratio (21). The standard method of calculating VD/VT (VD/VT[art]) utilizes the Enghoff modification of the Bohr equation, which includes measurements of , partial pressure of mixed expired CO2 (), and a correction for apparatus mechanical dead space volume (VDM) (21)

| (2) |

Although noninvasive estimates of VD/VT are included in commercial CPET systems (22), the accuracy of noninvasive VD/VT estimates is critically dependent on the accuracy in estimating (21). The accuracy of an estimated VD/VT value is important, particularly since obtaining arterial blood samples is frequently not feasible and because an abnormal VD/VT response often suggests the presence of underlying pulmonary vascular derangements; a pathophysiological feature that is becoming increasingly prevalent in the HFpEF population (12, 23). Indeed, HFpEF is associated with many cardiopulmonary abnormalities that could result in V/Q mismatch thereby increasing VD/VT, particularly during exercise. Moreover, VD/VT is a major contributor to exercise intolerance and an elevated ventilatory response in HFpEF (24), which are both widely used as prognostic indicators for heart failure. Since HFpEF is a common clinical population in which exertional dyspnea is frequently documented, and thus in whom CPET is regularly performed (11), the use of noninvasive estimates of and VD/VT could save patient discomfort, time, and cost.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to 1) determine the usefulness of and PJCO2 to estimate and 2) determine if or PJCO2 could be used to predict VD/VT[art] (VD/VT[ET] and VD/VT[J], respectively) by substituting either variable for in Eq. 2, in patients with HFpEF. We hypothesized that when compared with PJCO2 and VT/VT[J], and VD/VT[ET] would provide better estimates of and VD/VT[art] respectively, in patients with HFpEF.

METHODS

Participants

We evaluated 13 patients with HFpEF. Participants were eligible to participate if they had signs and symptoms of heart failure based on Framingham criteria (25), an ejection fraction ≥50%, and evidence of volume overload (e.g., pulmonary edema) confirmed by an elevated pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP) at rest of >15 mmHg and/or with exercise ≥25 mmHg. Participants with valvular or congenital heart disease, restrictive or infiltrative cardiomyopathy, acute myocarditis, New York Heart Association (NYHA) Class IV chronic heart failure or unstable chronic heart failure, a documented ejection fraction <50% at any time, manifest/provocable ischemic heart disease, or severe obstructive lung disease [forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) <40% predicted] were excluded. Before all testing, the purpose and protocols of all testing procedures were disclosed in detail and written and informed consent was obtained. The experimental procedures were reviewed and approved by the UT Southwestern Institutional Review Board (Ref. No: STU2019-0617).

Study Design

Participants visited the laboratory on two occasions separated by at least 48 h. During the first visit, participants underwent preparticipation health screening and performed pulmonary function testing according to ATS/ERS guidelines (26) and a maximal CPET to determine participant eligibility. During the second visit, participants performed a 6-min submaximal constant-load cycling test followed by a rapid incremental cycling test to exhaustion with temperature-corrected arterial blood gas samples (radial artery catheter) collected at rest, constant-load cycling, and peak exercise.

Submaximal Constant-Load Cycling Test

Following resting measurements, participants cycled at 20 W for 6 min on a recumbent cycle ergometer (Lode BV, Groningen, the Netherlands). This exercise work rate (WR) was set to represent the hemodynamic demands of activities of daily living. Heart rate and rhythm were monitored continuously using a 12-lead electrocardiogram, and blood pressure was monitored via arterial catheter waveforms. Gas exchange was measured to quantify minute ventilation (V̇e), V̇o2, carbon dioxide elimination (V̇co2), respiratory exchange ratio (RER), breathing frequency (Fb), VT, and using a customized breath-by-breath measurement system (Beck Integrative Physiological System, BIPS; KCBeck, Physiological Consulting, Liberty, UT) integrated with a mass spectrometer (Perkin-Elmer 1100). was sampled via a lateral port located on the mouthpiece.

Rapid Maximal Incremental Cycling Test

Following the submaximal constant-load cycling test, participants performed a rapid maximal incremental cycling test on the same cycle ergometer to determine peak exercise capacity. After a brief rest period, participants started cycling at an initial WR equivalent to 90% of V̇o2peak that was determined during the CPET performed on the first visit. The WR increased by 5 or 10 W each minute until the participant reached volitional exhaustion or symptom limitation. Heart rate and gas exchange variables were measured as aforementioned for the submaximal constant-load cycling test.

Arterial Catheterization

All participants underwent radial artery catheterization using a modified Seldinger technique with ultrasound guidance before testing during the second visit. Arterial placement was confirmed via observation of arterial pressure waveforms. During the same visit, a Swan-Ganz catheter was placed in the pulmonary artery via brachial or antecubital vein access under fluoroscopic guidance and was used to measure central blood temperature. Immediately following the elimination of sample-line dead space (i.e., 5 mL waste), 2 mL of arterial blood was withdrawn using a syringe with dry lithium heparin for gases and electrolytes for blood gas analysis. These blood gas samples were withdrawn over a 10-s period to reduce the fluctuations of blood gas tensions over a given respiratory cycle during the same time-frame in which and gas exchange measurements were made. Arterial blood gases were measured at rest, during the final minute of constant-load exercise, and during the final minute at peak exercise. The samples were immediately placed in an ice bath and were subsequently analyzed (ABL90 FLEX blood gas analyzer, Radiometer). Reference gases and commercial standards were used to calibrate the blood-gas analyzer before all testing.

Data Analysis

PJCO2 was derived from the prediction equation developed by Jones et al. (1): PJCO2 = 5.5 + 0.9 × − 2.1 × VT, where VT is in liters. VD/VT[art] was calculated using the Enghoff modification of the Bohr equation (21): VD/VT[art] = [( – )/] – (VDM/VT). VD/VT estimated from was calculated as: VD/VT[ET] = [( – )/] – (VDM/VT). VD/VT estimated from PJCO2 was calculated as: VD/VT[J] = [(PJCO2 – )/PJCO2] – (VDM/VT). VDM was measured to equal 0.18 L. was calculated as: 863 × V̇co2 (STPD)/ V̇e (BTPS).

Statistical Analysis

All data were analyzed using SPSS 22.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL). Paired t-tests were used to determine whether significant group differences existed between measured and estimated (i.e., and PJCO2), as well as measured VD/VT[art] and estimated VD/VT (VD/VT[ET] and VD/VT[J]) at rest, during constant-load exercise, and at peak exercise. The association between measured and estimated , and measured and estimated VD/VT was analyzed using Pearson correlation coefficients. Bland–Altman plots and 95% limits of agreement (LoA) were presented as an indicator of typical measurement error. Also, intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) were calculated to determine the level of agreement between measured and estimated , and measured and estimated VD/VT at rest, during constant-load exercise, and at peak exercise. ICC values were reported in accordance with Bland and Altman (27), where <0.2 is considered poor agreement, 0.21–0.40 as fair agreement, 0.41–0.60 as moderate agreement, 0.61–0.80 as good agreement, and 0.81–1.00 as very good agreement. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05 and all data are presented as means ± SD.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

Participant characteristics, including spirometric and pulmonary diffusing capacity variables are displayed in Table 1. All participants were middle or older age and had a preserved ejection fraction. Of the 13 participants included in the study, 12 were considered to have obesity based on body mass index (BMI). All participants at the time of the study were currently not smoking. Twelve out of 13 participants had never smoked, whereas the only participant with a history of smoking stopped 30 years prior (∼29 pack·yr history). Five out of the 13 participants had a diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea. Cardiorespiratory measures obtained at rest, submaximal constant-load exercise, and at peak exercise are shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Means ± SD | |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Age, yr | 69 ± 6 |

| Sex, male/female | 5/8 |

| Height, cm | 170 ± 10 |

| Weight, kg | 110 ± 14 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 38.4 ± 7.1 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction, % | 54 ± 2 |

| Pulmonary function | |

| FVC, %pred | 87 ± 16 |

| FEV1, %pred | 86 ± 17 |

| FEV1/FVC, % | 76 ± 11 |

| DLCO, %pred | 71 ± 20 |

| DLCO/VA, %pred | 108 ± 29 |

BMI, body mass index; DLCO, diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide; FEV1, forced expired volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity; VA, alveolar volume.

Table 2.

Cardiorespiratory parameters at rest and during exercise

| Means ± SD | |

|---|---|

| Rest | |

| V̇E, L/min | 12.44 ± 2.64 |

| VT, L | 0.75 ± 0.15 |

| Fb, breaths/min | 17.11 ± 4.06 |

| V̇o2, L/min | 0.33 ± 0.07 |

| V̇co2, L/min | 0.26 ± 0.06 |

| , Torr | 18.1 ± 2.9 |

| RER | 0.79 ± 0.05 |

| PCWP, mmHg | 5.9 ± 2.4 |

| Constant-load exercise at 20 W | |

| V̇E, L/min | 31.31 ± 3.98 |

| VT, L | 1.13 ± 0.25 |

| Fb, breaths/min | 28.98 ± 6.37 |

| V̇o2, L/min | 0.88 ± 0.17 |

| V̇co2, L/min | 0.77 ± 0.16 |

| , Torr | 21.2 ± 2.8 |

| RER | 0.87 ± 0.05 |

| PCWP, mmHg | 20.5 ± 6.6 |

| Peak exercise | |

| WR, W | 79 ± 29 |

| V̇E, L/min | 61.34 ± 18.78 |

| VT, L | 1.50 ± 0.59 |

| Fb, breaths/min | 43.56 ± 11.24 |

| V̇o2, L/min | 1.30 ± 0.41 |

| V̇o2, %predicted | 71 ± 17 |

| V̇o2, mL/min/kg | 11.85 ± 3.59 |

| V̇co2, L/min | 1.44 ± 0.57 |

| , Torr | 20.2 ± 3.4 |

| RER | 1.10 ± 0.11 |

| PCWP, mmHg | 32.6 ± 6.7 |

Fb, breathing frequency; PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; , partial pressure of mixed expired CO2; RER, respiratory exchange ratio; V̇E, minute ventilation; V̇co2, carbon dioxide elimination; V̇o2, oxygen consumption; VT, tidal volume; WR, work rate.

and Estimated

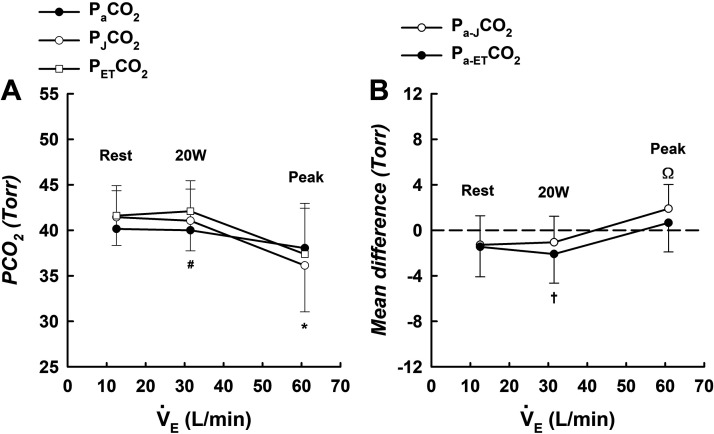

was not significantly different from (Fig. 1, A and B) at rest (−1.46 ± 2.63, P = 0.112) or peak exercise (0.66 ± 2.56, P = 0.392); however, overestimated at 20 W (−2.09 ± 2.55, P = 0.020). and were significantly correlated at rest (Fig. 2A), 20 W (Fig. 2B), and peak exercise (Fig. 2C). showed very good agreement with at rest (ICC = 0.824), 20 W (ICC = 0.862), and peak exercise (ICC = 0.953). Bland–Altman analyses show the agreement between and at rest (Fig. 3A), 20 W (Fig. 3B), and peak exercise (Fig. 3C).

Figure 1.

A: means ± SD values for , PJCO2, and at rest (n = 13), 20 W (n = 12), and peak exercise (n = 13); B: mean differences between and PJCO2 (Pa-JCO2), and and (Pa-ETCO2) at rest (n = 13), 20 W (n = 12), and peak exercise (n = 13). Data in both A and B were analyzed using paired t tests. *Significant difference between and PJCO2; #significant difference between and ; †significant difference between Pa-ETCO2 and zero; Ωsignificant difference between Pa-JCO2 and zero. n, Number of subjects; , partial pressure of arterial CO2; , partial pressure of end-tidal CO2; PJCO2, Jones corrected partial pressure of end-tidal CO2.

Figure 2.

Relationship between and (A–C) and and PJCO2 (D–F) at rest (n = 13), 20 W (n = 12), and peak exercise (n = 13). Relationships were analyzed using Pearson correlation coefficients. Dashed line: line of identity; solid line: linear regression. n, Number of subjects; , partial pressure of arterial CO2; , partial pressure of end-tidal CO2; PJCO2, Jones corrected partial pressure of end-tidal CO2.

Figure 3.

Bland–Altman plots (and 95% LoA) of the average of and vs. their difference (A–C) and the average of and PJCO2 vs. their difference (D–F) at rest (n = 13), 20 W (n = 12), and peak exercise (n = 13). LoA, limits of agreement; n, number of subjects; , partial pressure of arterial CO2; , partial pressure of end-tidal CO2; PJCO2, Jones corrected partial pressure of end-tidal CO2.

PJCO2 was not significantly different from (Fig. 1, A and B) at rest (−1.29 ± 2.57, P = 0.119) or 20 W (−1.06 ± 2.29, P = 0.154). However, PJCO2 underestimated at peak exercise (1.90 ± 2.13, P = 0.009). Also, PJCO2 and were significantly correlated at rest (Fig. 2D), 20 W (Fig. 2E), and peak exercise (Fig. 2F). PJCO2 showed very good agreement with at rest (ICC = 0.806), 20 W (ICC = 0.940), and peak exercise (ICC = 0.959). Bland–Altman analyses show the agreement between and PJCO2 at rest (Fig. 3D), 20 W (Fig. 3E), and peak exercise (Fig. 3F).

VD/VT and Estimated VD/VT

VD/VT[ET] was similar to VD/VT[art] (Fig. 5, A and B) at rest (−0.01 ± 0.03, P = 0.127) and peak exercise (0.01 ± 0.04, P = 0.210); however, VD/VT[ET] overestimated VD/VT[art] at 20 W (−0.02 ± 0.03, P = 0.025). VD/VT[ET] and VD/VT[art] were significantly correlated at rest (Fig. 5A), 20 W (Fig. 5B), and peak exercise (Fig. 5A). VD/VT[ET] showed very good agreement with VD/VT[art] at rest (ICC = 0.962), 20 W (ICC = 0.957), and peak exercise (ICC = 0.931). Bland–Altman analyses show the agreement between VD/VT[art] and VD/VT[ET] at rest (Fig. 6A), 20 W (Fig. 6B), and peak exercise (Fig. 6C).

Although VD/VT[J] was similar to VD/VT[art] at (Fig. 4, A and B) rest (−0.01 ± 0.03, P = 0.156) and 20 W (−0.01 ± 0.03, P = 0.133), VD/VT[J] underestimated VD/VT[art] at peak exercise (0.03 ± 0.04, P = 0.013). VD/VT[J] and VD/VT[art] were significantly correlated at rest (Fig. 5D), 20 W (Fig. 5E), and peak exercise (Fig. 5F). VD/VT[J] showed very good agreement with VD/VT[art] at rest (ICC = 0.963), 20 W (ICC = 0.959), and peak exercise (ICC = 0.924). Bland–Altman analyses show the agreement between VD/VT[art] and VD/VT[J] at rest (Fig. 6D), 20 W (Fig. 6E), and peak exercise (Fig. 6F).

Figure 4.

A: means ± SD values for VD/VT[art], VD/VT[J], and VD/VT[ET] at rest (n = 13), 20 W (n = 12), and peak exercise (n = 13); B: mean differences between VD/VT[art] and VD/VT[J] (VD/VT[art-J]), and VD/VT[art] and VD/VT[ET] (VD/VT[art-ET]) at rest (n = 13), 20 W (n = 12), and peak exercise (n = 13). Data in both A and B were analyzed using paired t tests. *Significant difference between VD/VT[art] and VD/VT[J]; #significant difference between VD/VT[art] and VD/VT[ET]; †significant difference between VD/VT[art-ET] and zero; Ωsignificant difference between VD/VT[art-J] and zero. n, Number of subjects; VD/VT, dead space to tidal volume ratio.

Figure 5.

Relationship between VD/VT[art] and VD/VT[ET] (A–C) and VD/VT[art] and VD/VT[J] (D–F) at rest (n = 13), 20 W (n = 12), and peak exercise (n = 13). Relationships were analyzed using Pearson correlation coefficients. Dashed line: line of identity; solid line: linear regression. n, Number of subjects; VD/VT, dead space to tidal volume ratio.

Figure 6.

Bland–Altman plot of the average of VD/VT[art] and VD/VT[ET] vs. their difference (A–C) and the average of VD/VT[art] and VD/VT[J] vs. their difference (D–F) at rest (n = 13), 20 W (n = 12), and peak exercise (n = 13). LoA, limits of agreement; n, number of subjects; VD/VT, dead space to tidal volume ratio.

DISCUSSION

Consistent with our original hypothesis, these are the first data to demonstrate that although and PJCO2 provide a reasonable estimate of at rest, overestimates during submaximal exercise but provides a better estimate of than PJCO2 does at peak exercise in patients with HFpEF. Similar observations were made when estimating VD/VT[art] using and PJCO2 in place of in the calculation, such that VD/VT[ET] overestimated VD/VT[art] during submaximal exercise but provided a better estimate of VD/VT[art] compared with VD/VT[J] at peak exercise.

HFpEF is associated with cardiopulmonary abnormalities that may impact the relationship between and (9, 10, 13–20). Our results agreed with previous studies in those with normal pulmonary function (1–6), such that and PJCO2 provided reasonable estimates of at rest in patients with HFpEF. Our findings also showed that and PJCO2 slightly overestimated . These findings contrast with previous studies in healthy individuals where estimates of have been shown to slightly underestimate measured at rest, which can be ascribed to the dilution of gas from poorly perfused alveoli in the apical regions of the lung due to gravitational forces acting upon pulmonary blood flow (28, 29). However, we must emphasize that the Pa-ETCO2 (−1.46 ± 2.63 Torr) and Pa-JCO2 (−1.29 ± 2.57 Torr) differences observed at rest in the present study were very small and well within previously published ranges (1–6). Thus, based on the findings of this study we would argue that the relationship between and is not significantly impacted at rest in patients with HFpEF. The fact that many compensated patients with HFpEF appear to exhibit normal resting hemodynamics, and that hemodynamic derangements seem to only develop during the stress of exercise supports this suggestion (11).

During exercise, has been shown to increase to a greater extent than in young healthy individuals (6). This is because the partial pressure of alveolar CO2 () fluctuates cyclically with breathing, and during exercise is greater than the average over the complete breathing cycle (30), particularly when CO2 production and delivery to the lungs and VT are increased, and alveolar air is continuously decreasing throughout exhalation (1). Cardiac output and pulmonary blood flow are also increased during exercise, resulting in improved V/Q matching (particularly in the apical regions of the lung) and increased (and thus, ) (29). The prediction equation developed by Jones et al. (i.e., PJCO2) serves to correct for the overestimation of by during exercise (1). However, Jones et al. (1) studied young healthy individuals and acknowledged that in patients with abnormal cardiopulmonary function, the use of this prediction equation could be misleading.

In keeping with Jones et al. (1), the results of this study is somewhat contrast to that of previous studies in younger individuals (1–6). Indeed, we demonstrated that although PJCO2 provides a reasonable estimate of during submaximal exercise, provides a better estimate of than PJCO2 does at peak exercise in patients with HFpEF. These findings agree with our previous work in older individuals (4), as well as work by others in patients with congestive heart failure (8), who reported that estimating from PJCO2 appeared unreliable when measured at peak exercise, irrespective of whether patients also presented with signs of obstructive lung disease (i.e., FEV1 less than 80% of predicted). Moreover, our findings also agree with Liu et al. (31) who compared the Pa-ETCO2 difference during exercise in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients with that in healthy individuals. Although Liu et al (31) did not report PJCO2, the difference between and was significantly less in those with COPD compared with healthy individuals at peak exercise, but the difference between and in COPD was similar (1.19 ± 2.04 Torr) to what we observed in patients with HFpEF in this study (0.66 ± 2.56 Torr).

The discordance between and PJCO2 during exercise has not been demonstrated before in patients with HFpEF. Based on our results, the reason as to why the predictability of by PJCO2 is affected cannot be determined. However, it is well known that cardiopulmonary abnormities that increase V/Q mismatching can alter the relationship between and . Studies have shown that values exceed values during exercise under conditions of V/Q mismatching (32–35). Indeed, individuals with unevenly distributed ventilation and perfusion exhibit lung units where the amount of ventilation is high relative to the amount of blood flow (28, 36). Expired gas coming from these units contains a Pco2 (i.e., ) that is less than . This is because the gas coming from areas with uneven V/Q matching dilutes gas coming from other areas of lung in which ventilation and perfusion are more closely matched, so that when measured during expiration, is lower than . A lower relative to is often observed in patients with pulmonary hypertension due to heterogenous pulmonary blood flow, resulting in a greater relative distribution of high V/Q lung units (37). It could be that a similar mechanism of V/Q mismatch contributed to the slightly lower (relative to ) values at peak exercise reported in the patients with HFpEF in this study. The fact that HFpEF is associated with a number of cardiopulmonary abnormalities such as pulmonary congestion (9, 10), elevated cardiac filling pressures and pulmonary hypertension (11, 12). impaired pulmonary diffusing capacity (13, 14), impaired pulmonary vascular recruitment/distension (14–16), and right ventricle-pulmonary artery uncoupling (17–19), all of which could increase V/Q mismatching, supports this suggestion.

Moreover, it is also possible that the relationship between and could be influenced by mechanical limitations that prevent VT expansion. Indeed, patients with heart failure typically exercise with a smaller VT (38). A smaller exercise VT could attenuate the rise in and potentially result in a smaller difference between and . The fact that VT at peak exercise (1.13 ± 0.25 L) was similar to that reported in previous studies of mechanical ventilatory limitation in heart failure (1.70 ± 0.20 L), but smaller compared with that reported in healthy individuals (2.43 ± 0.44 L) (3) supports the contention that a smaller VT could, in part, explain why provides a better estimate of than what PJCO2 does during exercise in patients with HFpEF. In addition to mechanical limitations imposed on VT expansion, Jones et al. (1) demonstrated that that magnitude of difference between and could also be affected by CO2 production and delivery to the lung. The cohort of patients tested in this study exhibited a reduced exercise capacity, evidenced by a reduced V̇o2peak expressed as a percent predicted value. As such, these patients likely did not achieve a V̇co2 at peak exercise that was sufficient to increase beyond , to the extent that has been shown previously in healthy individuals.

In light of that stated in the previous paragraph, it may be argued that the prediction equation developed by Jones et al. (PJCO2) overcorrects in situations where does not rise to a significantly higher value than during exercise, as may occur in disease states that exhibit cardiopulmonary abnormalities that have the propensity to result in uneven matching of V/Q, mechanical constraints that limit VT expansion, and a reduced exercise capacity. These findings confirm the need to directly measure during exercise, if one is to accurately assess pulmonary gas exchange efficiency in those with HFpEF, or other cardiac or pulmonary diseases.

VD/VT is a measure of physiological dead space and provides a valuable estimate of the degree of V/Q matching (21). With respect to estimating VD/VT[art], using or PJCO2 as substitutes for in the VD/VT calculation showed that VD/VT[ET] and VD/VT[J] provided reasonable estimates of VD/VT[art] at rest, whereas VD/VT[J] significantly underestimated VD/VT[art] at peak exercise. These findings are in keeping with that of previous studies in respiratory disease (39) and congestive heart failure (8) where VD/VT estimated from PJCO2 significantly underestimated VD/VT measured with at peak exercise. In addition, Vicken and Cosio (40) compared measured VD/VT with VD/VT estimated from during submaximal constant-load exercise in patients with various respiratory disorders. Although Vicken and Cosio (40) did not report on VD/VT estimated from PJCO2, VD/VT estimated from was similar to measured VD/VT; a finding that is similar to that observed in this study. Notably, in this study, the measured VD/VT[art] and estimated (VD/VT[ET] and VD/VT[J]) VD/VT values may only differ in the source of the variable in the Enghoff modification of the Bohr equation; this is provided that is not affected/diluted by any underlying pulmonary vascular abnormalities. Given that we did not find an identity between and estimates of (as evidenced by relatively large LoA), this may increase the risk of failing to identify possible underlying pulmonary vascular derangements as VD/VT[J] appears to underestimate VD/VT[art] in those with cardiopulmonary abnormalities, particularly if VD/VT is estimated with PJCO2.

In addition to demonstrating the usefulness of noninvasive estimates of and VD/VT in patients with HFpEF, we reported an abnormal increase in VD/VT[art] from rest to peak exercise (rest: 0.30 ± 0.07 vs. peak exercise: 0.35 ± 0.05), in conjunction with a positive Pa-ETCO2 difference at peak exercise. Taken together, these findings suggest that V/Q mismatching worsened during exercise in patients with HFpEF. The finding that V/Q mismatch worsened, as reflected by a progressive increase in VD/VT[art] during exercise, has not been previously demonstrated in patients with HFpEF. The reason as to why VD/VT[art] increased during exercise in the present study is unclear, but it is likely due to the development of high V/Q lung units during exercise, which has previously been demonstrated in patients with heart failure and pulmonary hypertension (37, 41). However, it should be noted that patients with HFpEF have not yet had their V/Q relationships analyzed by means of the multiple inert gas elimination technique (42), which remains the only way to quantify the distribution of V/Q relationships throughout the lung. Investigation into this question is beyond the scope of this study but represents an interesting avenue for further research.

Methodological Considerations

We must acknowledge that participants exercised in the recumbent position in this study. Thus, the findings of this study cannot be generalized to patients that perform invasive exercise testing in the supine position, which can alter V/Q relationships in the lung (and the relationship between and ) by removing gravitational forces acting upon pulmonary blood flow. Furthermore, the decision to perform exercise testing in the recumbent position was made purely to optimize patient comfort and to minimize logistical issues throughout the day of testing. Being positioned in the recumbent position meant that the arm that was catheterized could be placed securely on a portable table next to the participant, which ensured that the catheters remained in place. Also, having the patients in the recumbent position meant that resting periods (before, and in between, exercise bouts) could be taken while remaining on the recumbent cycle ergometer.

Conclusions

Our findings demonstrate that provides a better estimate of than PJCO2 does at peak exercise in patients with HFpEF. Similar observations were made when estimating VD/VT[art] using and PJCO2 in place of in the calculation, such that VD/VT[ET] provided a better estimate of VD/VT[art] compared with VD/VT[J] at peak exercise. Although we reported significant correlations, we did not find an identity between and estimates of , nor did we find an identity between VD/VT[art] and estimates of VD/VT[art], which were evidenced by relatively large LoA. Therefore, from our data, we emphasize that caution should be taken when estimating individual data, and estimates of and VD/VT should only be used if sampling arterial blood during CPET is not feasible in the patient with HFpEF. Sampling of arterial blood and direct measurement of remains the gold-standard clinical practice for calculating VD/VT.

GRANTS

B. N. Balmain is supported by an American Physiological Society (APS) Postdoctoral Fellowship. This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (Grant No.: 1P01HL137630) and Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital Dallas.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

B.N.B. and T.G.B. conceived and designed research; B.N.B. performed experiments; B.N.B. analyzed data; B.N.B., A.R.T., J.P.M., S.S., B.D.L., L.S.H., and T.G.B. interpreted results of experiments; B.N.B. prepared figures; B.N.B. drafted manuscript; B.N.B., A.R.T., J.P.M., S.S., B.D.L., L.S.H., and T.G.B. edited and revised manuscript; B.N.B., A.R.T., J.P.M., S.S., B.D.L., L.S.H., and T.G.B. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Raksa B. Moran, Sheryl Livingston, Margot Morris, Cindi Foulk, Marcus Payne, Mitchell Samels, and Stephanie Baird for their help with data collection and processing for this project.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jones NL, Robertson DG, Kane JW. Difference between end-tidal and arterial PCO2 in exercise. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol 47: 954–960, 1979. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1979.47.5.954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robbins PA, Conway J, Cunningham DA, Khamnei S, Paterson DJ. A comparison of indirect methods for continuous estimation of arterial PCO2 in men. J Appl Physiol (1985) 68: 1727–1731, 1990. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1990.68.4.1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernhardt V, Lorenzo S, Babb TG, Zavorsky GS. Corrected end-tidal PCO2 accurately estimates PaCO2 at rest and during exercise in morbidly obese adults. Chest 143: 471–477, 2013. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-0896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams JS, Babb TG. Differences between estimates and measured PaCO2 during rest and exercise in older subjects. J Appl Physiol (1985) 83: 312–316, 1997. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.83.1.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whipp BJ, Wasserman K. Alveolar-arterial gas tension differences during graded exercise. J Appl Physiol 27: 361–365, 1969. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1969.27.3.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wasserman K, Van Kessel AL, Burton GG. Interaction of physiological mechanisms during exercise. J Appl Physiol 22: 71–85, 1967. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1967.22.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson BD, Dempsey JA. Demand vs. capacity in the aging pulmonary system. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 19: 171–210, 1991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guazzi M, Marenzi G, Assanelli E, Perego GB, Cattadori G, Doria E, Agostini PG. Evaluation of the dead space/tidal volume ratio in patients with chronic congestive heart failure. J Cardiac Fail 1: 401–408, 1995. doi: 10.1016/S1071-9164(05)80009-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fermoyle CC, Stewart GM, Borlaug BA, Johnson BD. Effects of exercise on thoracic blood volumes, lung fluid accumulation, and pulmonary diffusing capacity in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 319: R602–R609, 2020. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00192.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reddy YNV, Obokata M, Wiley B, Koepp KE, Jorgenson Cc Egbe A, Melenovsky V, Carter Re Borlaug BA. The haemodynamic basis of lung congestion during exercise in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur Heart J 40: 3721–3730, 2019. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borlaug BA, Nishimura RA, Sorajja P, Lam CS, Redfield MM. Exercise hemodynamics enhance diagnosis of early heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail 3: 588–595, 2010. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.930701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoeper MM, Lam CSP, Vachiery JL, Bauersachs J, Gerges C, Lang IM, Bonderman D, Olsson KM, Gibbs JSR, Dorfmuller P, Guazzi M, Galiè N, Manes A, Handoko ML, Vonk-Noordegraaf A, Lankeit M, Konstantinides S, Wachter R, Opitz C, Rosenkranz S. Pulmonary hypertension in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a plea for proper phenotyping and further research. Eur Heart J 38: 2869–2873, 2017. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoeper MM, Meyer K, Rademacher J, Fuge J, Welte T, Olsson KM. Diffusion capacity and mortality in patients with pulmonary hypertension due to heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. JACC Heart Fail 4: 441–449, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2015.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olson TP, Johnson BD, Borlaug BA. Impaired pulmonary diffusion in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. JACC Heart Fail 4: 490–498, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2016.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fayyaz AU, Edwards WD, Maleszewski JJ, Konik EA, DuBrock HM, Borlaug BA, Frantz RP, Jenkins SM, Redfield MM. Global pulmonary vascular remodeling in pulmonary hypertension associated with heart failure and preserved or reduced ejection fraction. Circulation 137: 1796–1810, 2018. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.031608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lewis GD. The role of the pulmonary vasculature in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol 53: 1127–1129, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Borlaug BA, Kane GC, Melenovsky V, Olson TP. Abnormal right ventricular-pulmonary artery coupling with exercise in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur Heart J 37: 3293–3302, 2016. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guazzi M, Dixon D, Labate V, Beussink-Nelson L, Bandera F, Cuttica MJ, Shah SJ. RV contractile function and its coupling to pulmonary circulation in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: stratification of clinical phenotypes and outcomes. JACC Cardiovasc Imag 10: 1211–1221, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2016.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Melenovsky V, Hwang SJ, Lin G, Redfield MM, Borlaug BA. Right heart dysfunction in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur Heart J 35: 3452–3462, 2014. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Houstis NE, Eisman AS, Pappagianopoulos PP, Wooster L, Bailey CS, Wagner PD, Lewis GD. Exercise intolerance in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: diagnosing and ranking its causes using personalized O2 pathway analysis. Circulation 137: 148–161, 2018. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.029058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lewis DA, Sietsema KE, Casaburi R, Sue DY. Inaccuracy of noninvasive estimates of VD/VT in clinical exercise testing. Chest 106: 1476–1480, 1994. doi: 10.1378/chest.106.5.1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Thoracic Society; American College of Chest Physicians. ATS/ACCP Statement on cardiopulmonary exercise testing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 167: 211–277, 2003. doi: 10.1164/rccm.167.2.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Borlaug BA, Obokata M. Is it time to recognize a new phenotype? Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction with pulmonary vascular disease. Eur Heart J 38: 2874–2878, 2017. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Iterson EH, Johnson BD, Borlaug BA, Olson TP. Physiological dead space and arterial carbon dioxide contributions to exercise ventilatory inefficiency in patients with reduced or preserved ejection fraction heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 19: 1675–1685, 2017. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Löfström U, Hage C, Savarese G, Donal E, Daubert JC, Lund LH, Linde C. Prognostic impact of Framingham heart failure criteria in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. ESC Heart Fail 6: 830–839, 2019. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.12458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, Burgos F, Casaburi R, Coates A, Crapo R, Enright P, van der Grinten CP, Gustafsson P, Jensen R, Johnson DC, MacIntyre N, McKay R, Navajas D, Pedersen OF, Pellegrino R, Viegi G, Wanger J, Force AET; ATS/ERS Task Force. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J 26: 319–338, 2005. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00034805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet 327: 307–310, 1986. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(86)90837-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Petersson J, Glenny RW. Gas exchange and ventilation-perfusion relationships in the lung. Eur Respir J 44: 1023–1041, 2014. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00037014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.West JB. Distribution of blood and gas in the lung. Br Med Bull 19: 53–58, 1963. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a070007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dubois AB, Britt AG, Fenn WO. Alveolar CO2 during the respiratory cycle. J Appl Physiol 4: 535–545, 1952. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1952.4.7.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu Z, Vargas F, Stansbury D, Sasse SA, Light RW. Comparison of the end-tidal arterial PCO2 gradient during exercise in normal subjects and in patients with severe COPD. Chest 107: 1218–1224, 1995. doi: 10.1378/chest.107.5.1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Iterson EH, Olson TP. Use of 'ideal' alveolar air equations and corrected end-tidal PCO2 to estimate arterial PCO2 and physiological dead space during exercise in patients with heart failure. Int J Cardiol 250: 176–182, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.West JB, Wang DL, Prisk GK, Fine JM, Bellinghausen A, Light M, Crouch DR. Noninvasive measurement of pulmonary gas exchange: comparison with data from arterial blood gases. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 316: L114–L118, 2019. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00371.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamanaka MK, Sue DY. Comparison of arterial-end-tidal PCO2 difference and dead space/tidal volume ratio in respiratory failure. Chest 92: 832–835, 1987. doi: 10.1378/chest.92.5.832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yasunobu Y, Oudiz RJ, Sun X-G, Hansen JE, Wasserman K. End-tidal PCO2 abnormality and exercise limitation in patients with primary pulmonary hypertension. Chest 127: 1637–1646, 2005. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.5.1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robertson HT. Dead space: the physiology of wasted ventilation. Eur Respir J 45: 1704–1716, 2015. [Erratum in Eur Respir J 46: 1226, 2015]. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00137614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scheidl SJ, Englisch C, Kovacs G, Reichenberger F, Schulz R, Breithecker A, Ghofrani HA, Seeger W, Olschewski H. Diagnosis of CTEPH versus IPAH using capillary to end-tidal carbon dioxide gradients. Eur Respir J 39: 119–124, 2012. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00109710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johnson BD, Beck KC, Olson LJ, O'Malley KA, Allison TG, Squires RW, Gau GT. Ventilatory constraints during exercise in patients with chronic heart failure. Chest 117: 321–332, 2000. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.2.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zimmerman MI, Miller A, Brown LK, Bhuptani A, Sloane MF, Teirstein AS. Estimated vs actual values for dead space/tidal volume ratios during incremental exercise in patients evaluated for dyspnea. Chest 106: 131–136, 1994. doi: 10.1378/chest.106.1.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vincken W, Cosio M. Can VD/VT accurately be calculated during exercise using end-tidal PCO2? (Abstract). Am Rev Respir Dis 145: A587, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Clark AL, Volterrani M, Swan JW, Coats AJS. Ventilation-perfusion matching in chronic heart failure. Int J Cardiol 48: 259–270, 1995. doi: 10.1016/0167-5273(94)02267-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hopkins SR, Wagner PD. The Multiple Inert Gas Elimination Technique (MIGET). New York: Springer, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]