Abstract

Background

DIALOG+ is a patient-centred, solution-focused intervention, which aims to make routine patient-clinician meetings therapeutically effective. Existing evidence suggests that it is effective for patients with psychotic disorders in high-income countries. We tested the effectiveness of DIALOG + for patients with depressive and anxiety disorders in Bosnia and Herzegovina, a middle-income country.

Methods

We conducted a parallel-group, cluster randomised controlled trial of DIALOG+ in an outpatient clinic in Sarajevo. Patients inclusion criteria were: 18 years and older, a diagnosis of depressive or anxiety disorders, and low quality of life. Clinicians and their patients were randomly allocated to either the DIALOG + intervention or routine care in a 1:1 ratio. The primary outcome, quality of life, and secondary outcomes, psychiatric symptoms and objective social outcomes, were measured at 6- and 12-months by blinded assessors.

Results

Fifteen clinicians and 72 patients were randomised. Loss to follow-up was 12% at 6-months and 19% at 12-months. Quality of life did not significantly differ between intervention and control group after six months, but patients receiving DIALOG + had significantly better quality of life after 12 months, with a medium effect size (Cohen's d = 0.632, p = 0.007). General symptoms as well as specifically anxiety and depression symptoms were significantly lower after six and 12 months, and the objective social situation showed a statistical trend after 12 months, all in favour of the intervention group. No adverse events were reported.

Limitations

Delivery of the intervention was variable and COVID-19 affected 12-month follow-up assessments in both groups.

Conclusion

The findings suggest DIALOG + could be an effective treatment option for improving quality of life and reducing psychiatric symptoms in patients with depressive and anxiety disorders in a low-resource setting.

Keywords: Quality of life, Depression, Anxiety, Computer-assisted therapy, Mental health services

Highlights

-

•

As DIALOG+ is used within routine clinical meeting, no additional staff or resources are required for implementation.

-

•

DIALOG+ utilises existing patient resources, is not difficult to implement and is inexpensive.

-

•

Eighty patients met our inclusion criteria and 72 agreed to participate and completed a baseline assessment.

-

•

At 12 months, the intervention group showed a significantly better quality of life.

-

•

Patients in the intervention group had significantly lower levels of symptoms time with medium to large effect sizes.

-

•

The objective social situation did not differ significantly between the two groups after six months.

-

•

The objective social situation showed a statistical trend towards a more positive outcome in the intervention group.

-

•

Findings suggest DIALOG + could be an effective treatment for improving quality of life and reducing psychiatric symptoms.

1. Introduction

Depressive and anxiety disorders are a global health problem. By World Health Organization (WHO) estimates, the global prevalence of depressive disorders is 4.4% and anxiety disorders 3.6% (World Health Organization, 2017). The two conditions are frequently comorbid and at least one-third of patients experience moderate to severe forms of these disorders (World Health Organization, 2017; Ferrari et al., 2013). In 2019, depressive and anxiety disorders were respectively ranked as the first and sixth largest contributors to disability globally. Moreover, 80% of this disease burden occurs in low-and middle-income countries (World Health Organization, 2017).

A substantial part of the suffering experienced by people with depressive and anxiety disorders relates to poor quality of life (Cuijpers et al., 2012; Barrera and Norton, 2009; Kessler et al., 2003). Depression and anxiety negatively impact social functioning, economic and education outcomes, and family and interpersonal relationships (Barrera and Norton, 2009; Papakostas et al., 2004). Poor quality of life often persists after symptoms improve and is associated with an increased likelihood of relapse (IsHak et al., 2011, 2013; Rodriguez et al., 2005). As a result, treatment options must do more than simply treat the symptoms of depression and anxiety, and instead work to improve patients’ quality of life.

DIALOG+ is a therapeutic intervention based on cognitive-behavioural therapy and solution-focused therapy, which aims to make routine meetings between patients and mental health professionals more effective (Priebe et al., 2017). With the assistance of a tablet computer, patients rate and discuss their satisfaction with eight life domains and three treatment options. Patients then choose up to three areas to discuss further with clinicians through a four-step, solution-focused process. DIALOG + has proven to be a successful therapeutic model for the treatment of patients with psychosis, for whom it has enhanced quality of life, reduced psychiatric symptoms, and improved social outcomes.10 11

There is emerging evidence that DIALOG + could be a feasible and effective resource for patients with mental illness in low-resource settings (Saleem et al., et al., Hunter et al., 2020). In high-income countries, it has been proven to lower treatment costs for patients with psychosis and reduce the referral to specialist mental health services (Omer et al., 2016). As DIALOG+ is used within routine clinical meeting, no additional staff or resources are required for implementation. It utilises existing patient resources, is not difficult to implement and is inexpensive.10 11 This especially relevant in Bosnia and Herzegovina, which has a high prevalence of depressive and anxiety disorders, and a lack of qualified staff and resources to provide specialist care for patients with severe mental illness (Priebe et al., 2010).

We aim to assess the effectiveness of DIALOG + for improving the quality of life and reducing mental health symptoms in patients with depressive and anxiety disorders in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

Between March 2018 and July 2020, we conducted a parallel-group, cluster randomised controlled trial at the Department of Psychiatry at the Clinical Centre University of Sarajevo. Further study details are available in a published protocol (Priebe et al., 2019). The trial was prospectively registered within the ISRCTN Registry (ISRCTN13347129) and ethical approval was obtained from the Ethical Committee at the Clinical Centre of the University of Sarajevo and the Queen Mary Ethics of Research Committee (ref: QMERC2018/66).

2.2. Participants and setting

Clinicians were recruited from the Clinical Centre University of Sarajevo. Inclusion criteria were a qualification in any health care profession (e.g. psychiatrist, psychologist, nurse, social worker), more than three months experience of working with patients with severe mental illnesses, and no plans to leave the post in the next six months. Researchers contacted potentially eligible clinicians to provide information about the study, and interested parties were screened and, if eligible, recruited.

The caseloads of recruited clinicians were screened for eligible patients. In order to participate, patients were required to be: 18 years or older, capable of providing informed consent, living with a diagnosis of depressive or anxiety disorders (ICD-10: F30-F39 and F40-F48, excluding bipolar disorder) for six months or more, and experiencing poor quality of life (defined as a mean Manchester Short Assessment of Quality of Life (MANSA) (Priebe et al., 1999) score of ≤5). Patients were excluded if they were participating in another research study or were an inpatient at the time of recruitment. Eligible participants were contacted by their clinician or a researcher and provided written information about the study. Those patients providing written consent completed eligibility screening for poor quality of life using the MANSA questionnaire.

2.3. Procedure

A cluster-randomisation design was used to avoid potential contamination of the practice of clinicians when treating patients in both groups. Randomisation was conducted by an external researcher using sequential computer-generated random numbers to determine allocation. This information was then provided to the unblinded research coordinator at the trial site. Clinicians and their patients were randomly assigned to either the DIALOG + intervention or the control group, with an allocation ratio of 1:1. Following randomisation, clinicians in the intervention group received DIALOG + training. All participants received treatment as usual, with participants in the intervention arms additionally attending monthly DIALOG + sessions.

Treatment as usual consisted of the therapy that patients in both of the groups were using at the moment of their recruitment. Almost all of the patients were on some form of pharmacotherapy that was prescribed by their psychiatrist (antidepressant or anxiolytic therapy, depending on their primary diagnosis). In addition to the pharmacotherapy, patients in the control group had routine “non-DIALOG+” meetings with their clinicians, varying from once per month to once in every three months. For patients in intervention arm, routine meetings were replaced by monthly DIALOG + sessions.

DIALOG+ is a therapeutic intervention based on elements of cognitive-behavioural therapy and solution-focused therapy, delivered via an application on a tablet computer. It consists of two parts. In the first part, the clinicians ask questions about patient satisfaction with eight life domains (mental health, physical health, job situation, accommodation, leisure activities, family relationships, friendships and personal safety) and three treatment domains (medication, meetings with mental health professionals and practical help). The patient rates their satisfaction on a scale from 1 (‘totally dissatisfied’) to 7 (‘totally satisfied’) and chooses up to three domains that they would like to discuss further. The domains are addressed using a four-step approach: 1) understanding the problem and emphasising what works; 2) looking forward to solution-focussed goals; 3) considering actions the patient, their friends/family and the clinician can take; and 4) agreeing on actions, which will be reviewed at the next meeting.11 14

2.4. Outcome measures

All data were collected using a standardised, case report form. At baseline, demographic information was collected for patients and clinicians, and primary mental health diagnoses obtained from patients’ histories based on their most recent psychiatric assessment. Six- and 12-month data collection was conducted by blinded assessors.

Our primary outcome was subjective quality of life at 6-months, measured as a mean Manchester Short Assessment of Quality of Life (MANSA) scores (Priebe et al., 1999). The MANSA consists of 12 items relating to different aspects of life, which are rated from 1 (‘Couldn't be worse’) to 7 (‘Couldn't be better’).

Secondary outcomes were general psychiatric symptom severity, symptoms of depression and anxiety, and objective social outcomes. General symptoms were observer-rated on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (Zanello et al., 2013). The BPRS is a 24-item observer-rated scale, in which each symptom is assessed and rated between 1 (‘Not present’) and 7 (‘Extremely severe’). BPRS ratings were conducted by three different researchers, all of whom were trained in the instrument and completed interrater-reliability assessment before starting baseline data collection. The specific symptoms of anxiety and depression were self-rated using the depression and anxiety subscales of the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21) (Antony et al., 1998). Scores are calculated by summing the scores for the seven depression items and the seven anxiety items. Objective social outcomes were assessed through SIX (Social Outcomes Index) (Priebe et al., 2008) which captures patient employment, accommodation and social contacts. SIX ranges from 0 (Poorest social outcome) to 6 (Best social outcome).

At the end of the six-month period, semi-structured in-depth interviews were conducted in Bosnian to examine the experiences of patients and clinicians who used the DIALOG + intervention. An interview topic guide was developed to gain insights into patient experiences. Each interview was audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Purposive sampling was used to capture patients with varying levels of meeting attendance and with different outcomes.

2.5. Statistical analysis

A blinded, external research conducted all analysis in accordance with a statistical analysis plan that was signed and agreed before data extraction. Means, standard deviations and ranges were used to compare continuous variables, and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. To compare changes in mean outcomes scores at 6 and 12 months in the intervention and control groups, generalised mixed linear model was used with a fixed effect for treatment and the baseline value of the given outcome and a random effect for clinician. Social outcomes index (SIX) at 6 and 12 months was analysed using a proportional odds model with treatment fitted as a fixed effect and a random intercept. Cohen's d is derived from the raw data and calculated as a standardised measure of effect.

An additional per-protocol analysis was performed on primary and secondary outcomes. This analysis followed the same methodology but compared controls with only those patients with at least three completed sessions. According to our pre-defined criterion, receiving three or more DIALOG + sessions within the intervention period was considered a per-protocol completed intervention.

3. Results

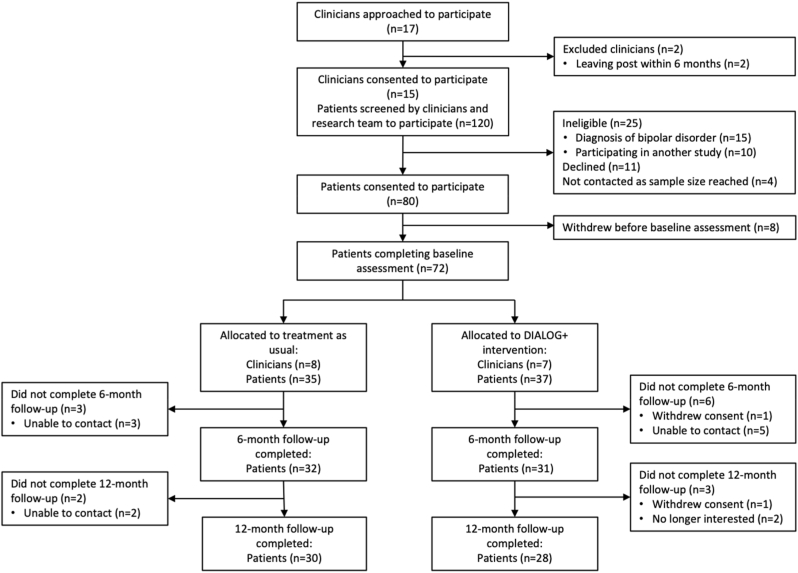

Fifteen clinicians were recruited to participate in the study, and 120 of their patients’ records screened for eligibility. (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

CONSORT participant flow diagram.

Eighty patients met our inclusion criteria and 72 agreed to participate and completed a baseline assessment. Due to the nature of cluster randomisation, seven clinicians and 37 patients were randomly assigned to the intervention group, and eight clinicians and 35 patients to the control group. An additional clinician was recruited post-randomisation to replace one clinician in the control group who left their post before the intervention period commenced.

The characteristics of patients in the two groups are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the patient participants (n = 72).

| Total (n = 72) | Intervention group (n = 37) | Control group (n = 35) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age: mean years (range) | 51 (20–74) | 50 (20–67) | 52 (22–74) |

| Female (n, %) | 52 (72%) | 26 (70%) | 26 (74%) |

| Primary psychiatric diagnosis | |||

| F30, F32-39 | 35 (49%) | 15 (41%) | 20 (57%) |

| F40-48 | 37 (51%) | 22 (59%) | 15 (43%) |

| Highest level of education | |||

| Elementary of less | 8 (11%) | 4 (11%) | 4 (11%) |

| Secondary | 46 (64%) | 22 (60%) | 24 (69%) |

| Tertiary/further education | 17 (24%) | 11 (30%) | 6 (17%) |

| Other | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) |

| Employment status | |||

| Employed full-time | 25 (35%) | 9 (24%) | 16(46%) |

| Employed part-time | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) |

| Unemployed | 21 (30%) | 15 (38%) | 6 (18%) |

| Student | 6 (8%) | 3 (8%) | 3 (9%) |

| Retired due to disability | 14 (19%) | 7 (18%) | 7 (21%) |

| Retired on old age pension | 3 (4%) | 1 (3%) | 2 (6%) |

| Supported by family pension | 2 (3%) | 2 (5%) | 0 (0%) |

| Living situation | |||

| Living alone | 59 (82%) | 30 (81%) | 29 (83%) |

| Living with partner/family | 13 (18%) | 7 (19%) | 6 (17%) |

| Marital status | |||

| Single | 19 (26%) | 10 (27%) | 9 (25%) |

| Married | 40 (56%) | 20 (54%) | 20 (57%) |

| Co-habiting/civil partnership | 2 (3%) | 2 (5%) | 0 (0%) |

| Separated | 2 (3%) | 2 (5%) | 0 (0%) |

| Divorced | 3 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (9%) |

| Widow/widower | 6 (8%) | 3 (18%) | 3 (9%) |

| Accommodation | |||

| Independent accommodation | 71 (98%) | 39 (100%) | 32 (97%) |

| Homeless | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) |

The mean age of patients was 51 (range 20–74). They were predominantly female (72%) and evenly split between a diagnosis of depressive (49%) and anxiety disorders (51%) (Table 1). From the 15 clinicians recruited, 8 were psychiatrists, 4 were psychiatric residents and 3 were psychologists.

On average, each participant received 2.2 DIALOG + sessions over a six-month intervention period (range 0–4). Nineteen patients (51%) attended three or more sessions and were therefore regarded as having completed the intervention in line with the protocol. Seven patients (19%) received no sessions. Two of the included clinicians received training with considerable delay and delivered a reduced number of sessions. One of them had five patients but delivered only one session in total. The mean session time was 34 min (range 18–72).

3.1. Outcomes

Primary and secondary outcome measures at baseline, six months and twelve months are presented in Table 2. There was no significant difference in the primary outcome of quality of life between the intervention and control groups after six months. At 12 months, the intervention group showed a significantly better quality of life, with an effect size of 0.63 (p = 0.007).

Table 2.

Primary and secondary outcomes at baseline, 6-months and 12-months.

| Intervention |

Control |

Coefficient [95% CI]a | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | mean (SD) | n | mean (SD) | ||||

| MANSA | Baseline | 37 | 4.0 ± 0.7 | 35 | 4.2 ± 0.5 | … | … |

| 6 months | 31 | 4.5 ± 1.0 | 32 | 4.2 ± 0.6 | −0.22 [-0.61 – 0.17] | 0.167 | |

| 12 months | 28 | 4.5 ± 1.0 | 30 | 4.0 ± 0.5 | −0.52 [-0.89 to −0.15] | 0.007 | |

| SIX | Baseline | 37 | 4.3 ± 1.4 | 35 | 4.7 ± 1.2 | … | … |

| 6 months | 31 | 4.2 ± 1.1 | 32 | 4.6 ± 1.1 | 0.32 [-1.79 – 2.44] | 0.764 | |

| 12 months | 28 | 4.5 ± 1.2 | 30 | 4.3 ± 1.2 | 1.20 [-0.07 – 2.46] | 0.063 | |

| BPRS | Baseline | 37 | 39.0 ± 7.0 | 35 | 36.0 ± 6.0 | … | … |

| 6 months | 31 | 34.2 ± 6.6 | 32 | 37.2 ± 5.7 | 4.04 [0.65–7.44] | 0.021 | |

| 12 months | 28 | 34.1 ± 6.7 | 30 | 40.2 ± 4.2 | 7.03 [3.34–10.72] | <0.001 | |

| DASS (depression) | Baseline | 37 | 20.2 ± 12.9 | 35 | 16.9 ± 10.2 | … | … |

| 6 months | 31 | 13.4 ± 12.0 | 32 | 17.9 ± 12.5 | 0.54 [0.28–0.79] | <0.001 | |

| 12 months | 28 | 6.9 ± 5.5 | 30 | 11.3 ± 4.9 | 5.24 [2.39–8.10] | 0.001 | |

| DASS (anxiety) | Baseline | 37 | 18.7 ± 11.5 | 35 | 15.4 ± 10.7 | … | … |

| 6 months | 31 | 13.5 ± 10.7 | 32 | 16.3 ± 10.7 | 0.71 [0.47–0.94] | <0.001 | |

| 12 months | 28 | 5.8 ± 4.8 | 30 | 9.8 ± 4.7 | 5.71 [2.96–8.46] | <0.001 | |

For the MANSA, SIX and DASS scales, regression coefficients derived from mixed linear models with a fixed effect for treatment and baseline scores and a random effect for clinician cluster. For the SIX proportional odds models with treatment fitted as a fixed effect and a random intercept.

With respect to secondary outcomes, the intervention group displayed fewer general psychiatric symptoms as measured on the BPRS after six months (Cohen's d = 0.49, p = 0.021) and after 12 months (d = 1.09, p < 0.001). Patients in the intervention group had significantly lower levels of symptoms of depression and anxiety at both points of time with medium to large effect sizes.

The objective social situation did not differ significantly between the two groups after six months, but showed a statistical trend towards a more positive outcome in the intervention group after 12 months. There were no adverse effects reported in either group.

3.2. Further analysis

At six and twelve months, the per protocol-analysis provided similar results to the available case analysis for all primary and secondary outcomes. However, at 12-months, patients who had completed three or more DIALOG + sessions had a significantly more favourable objective social situation as measured on the SIX as compared to the controls (coefficient = 1.37 [0.08–2.66], p = 0.038).

3.3. Patient experiences

Interviews were conducted with 15 patients at the conclusion after the six-month intervention period had ended. Most patients reported positive experiences of using the DIALOG + intervention.

“Only positive. I can really say that. Even in this difficult situation [COVID-19 lockdown] those experiences are helping me to better cope.”

“My experiences are mostly positive, considering I have a long-standing experiences with different forms of treatment and different experts, so I can say that this experience, not only reminded me of things, for example different ways for me to overcome my anxiety and depression, but it took me a step further … Talking with the clinician … we went a few steps further with the advices on how to help oneself.”

“To be honest, I always expect a solution to the problem that I have … I established what I already knew and added now thing to that knowledge. And now I can use them as tools to fight with that diagnosis that I have.”

Some patients, however, reported difficulties finding the time to attend all sessions and paying for transportation to and from sessions.

“For me, it was a problem, to take that time, considering all of my problems, to take the time to get there, to be there, to get back, and so on … And I have to pay for the transportation, I have to pay for the return trip, and so on … And there were multiple sessions and I use multiple transportations to get there, so maybe those material costs should have been taken into the consideration.”

4. Discussion

This is the first randomised controlled trial of the DIALOG + intervention in patients with depressive and anxiety disorders in the world. The intervention was shown to be an effective intervention for these patients in a middle-income country. Quality of life was significantly better in the intervention group after 12 months. Measures of general symptoms and specifically of anxiety and depression showed significant benefits for the intervention group at both six- and twelve-month follow-ups with medium to large effect sizes. Social outcomes showed a trend for improvement after one year. Patient experiences described in interviews were largely positive.

4.1. Strengths and limitations

We conducted a randomised controlled trial within pre-existing structures of routine meetings, enhancing the generalisability of our findings to similar settings. Outcomes were measured by blinded assessors using both self-reported and observer-rated scales, which captured both objective and subjective outcomes. Observer-rated and self-rated symptoms showed consistent findings.

A limitation of our study was the variable implementation of the intervention by some clinicians, resulting in patients receiving on average 2.2 sessions during the intervention period. This was mainly a consequence of delays in the training of two clinicians. The COVID-19 restrictions meant that 12-month assessments needed to be conducted by telephone rather than in person. One might also see the small sample size as a limitation. As a result of the sample size, the statistical power was indeed limited. However, even with the small sample the study did yield clear and statistically significant results on quality of life after one year and on all symptom measures at all time points. A larger sample would have been likely to provide more accuracy, but not to add value to the overall finding that the intervention was effective in this patient group.

4.2. Comparison with the wider literature

Our findings are comparable to a previous randomised controlled trial of DIALOG+ in patients with schizophrenia which was conducted in the United Kingdom. In that trial, DIALOG + led to improvements of quality of life and symptoms throughout a six-month intervention and a further six-month follow-up period (Priebe et al., 2015; Priebe et al., 2007). However, this was the first RCT of DIALOG+ in patients with anxiety and depression rather than psychosis, and the effect sizes in this study are even larger than in the RCT with patients with long-term schizophrenia. Since this was a small trial, the results should be interpreted with caution. Nevertheless, one may speculate as to whether DIALOG + as an intervention that activates existing personal and social resources of patients might be even more effective in patients with anxiety and depression. These patients might have more such resources that can be utilised in social networks and relationships than patients with long-term schizophrenia (Priebe et al., 2014).

DIALOG + appears to be at least as effective for improving quality of life and reducing symptom severity in patients with depression and anxiety as other widely implemented psychological interventions. A meta-analysis of the impact of psychotherapies on quality of life in patients with clinical depression found a standardised effect size of 0.33 [95%CI 0.24–0.42] (Kolovos et al., 2016), while a meta-analysis of the effect of CBT on depressive and anxiety disorders found an effect size of 0.47 [95%CI 0.33–0.62]. (Zhang et al., 2019).

Evidence from low- and middle-income countries is by comparison limited. A meta-analysis of psychological treatments for depression and anxiety disorders in LMICs found an overall effect size of 1.02 [ 95%CI: 0.76–1.28]. However, the authors warn that this is likely an overestimate due to the high degree of unexplained heterogeneity, evidence of publication bias, the small number of studies and the choice of control group (treatment as usual vs waiting list vs active-control) (Van't Hof et al., 2011). Also, most of the included interventions are psychological treatments requiring a defined number of sessions with a qualified psychologist or other specialised mental health professional. In contrast, DIALOG + can be implemented flexibly and used within routine meetings that happen anyway. It is therefore less resource-intensive than other interventions and does not require specialised services to be established and funded. It may therefore be seen as very encouraging that this intervention achieved medium to large effect sizes in the reported trial, despite limited implementation.

5. Conclusions

Emerging evidence from other low- and middle-income countries suggesting DIALOG+ is feasible and effective for patients with depression and anxiety (Saleem et al. et al.). Qualitative research conducted in South Eastern Europe has shown a willingness amongst patients and clinicians to use the DIALOG + intervention (Hunter et al., 2020). Given that routine clinical visits are already part of a usual care for people with severe mental illness in Bosnia and Herzegovina, incorporating DIALOG + as a structured, patient-centred approach could enhance the therapeutic effectiveness without any changes to the organisation of routine consultations. Future research should explore whether similar results can be achieved in other low-and-middle countries and how the intervention can best be implemented and sustained in routine care.

Author contribution statement

S.S.M. is the first author. She wrote the draft versions of the article and did the data collection, carried out the trial. S. J. did the data analysis and interpretation.

M.M. and H.S. helped with the data collection and assessment.

E.B. did the critical revision of the paper, and coordinated the study.

S.P. made the conceptual design of the work, critical revision and final approval of the paper.

A.Dž.K. made the conceptual design of the work, obtained Ethical approval, verified analytical methods, critical revision and final approval of the paper. She was the immediate supervisor of the whole study.

All authors discussed the results, provided critical feedback and contributed to the final version of the manuscript.

Funding statement

This research was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) (Global Health Research Group on Developing Psychosocial Interventions for Mental Health Care, project reference 16/137/97) using UK aid from the UK Government to support global health research. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the UK Department of Health and Social Care.

Declaration of competing interest

All authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) (Global Health Research Group on Developing Psychosocial Interventions for Mental Health Care, project reference 16/137/97) using UK aid from the UK Government to support global health research.

References

- Antony M.M., Bieling P.J., Cox B.J., et al. Psychometric properties of the 42-item and 21-item versions of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales in clinical groups and a community sample. Psychol. Assess. 1998;10(2):176. [Google Scholar]

- Barrera T.L., Norton P.J. Quality of life impairment in generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, and panic disorder. J. Anxiety Disord. 2009;23(8):1086–1090. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers P., Beekman A.T.F., Reynolds C.F. Preventing depression: a global priority. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2012;307(10):1033–1034. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari A.J., Charlson F.J., Norman R.E., et al. Burden of depressive disorders by country, sex, age, and year: findings from the global burden of disease study 2010. PLoS Med. 2013;10(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter J., McCabe R., Francis J.J., et al. Implementing a mental health intervention in low-and-middle-income countries in Europe: is it all about resources? GLOBAL PSYCHIATRY. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- IsHak W.W., Greenberg J.M., Balayan K., et al. Quality of life: the ultimate outcome measure of interventions in major depressive disorder. Harv. Rev. Psychiatr. 2011;19(5):229–239. doi: 10.3109/10673229.2011.614099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IsHak W.W., Greenberg J.M., Cohen R.M. Predicting relapse in major depressive disorder using patient-reported outcomes of depressive symptom severity, functioning, and quality of life in the individual burden of illness index for depression (IBI-D) J. Affect. Disord. 2013;151(1):59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.05.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R.C., Berglund P., Demler O., et al. The epidemiology of major depressive DisorderResults from the national comorbidity survey replication (NCS-R) J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2003;289(23):3095–3105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolovos S., Kleiboer A., Cuijpers P. Effect of psychotherapy for depression on quality of life: meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatr. 2016;209(6):460–468. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.115.175059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omer S., Golden E., Priebe S. Exploring the mechanisms of a patient-centred assessment with a solution focused approach (DIALOG+) in the community treatment of patients with psychosis: a process evaluation within a cluster-randomised controlled trial. PLoS One. 2016;11(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papakostas G.I., Petersen T., Mahal Y., et al. Quality of life assessments in major depressive disorder: a review of the literature. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatr. 2004;26(1):13–17. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2003.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priebe S., Huxley P., Knight S., et al. Application and results of the manchester Short assessment of quality of life (mansa) Int. J. Soc. Psychiatr. 1999;45(1):7–12. doi: 10.1177/002076409904500102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priebe S., McCabe R., Bullenkamp J., et al. Structured patient–clinician communication and 1-year outcome in community mental healthcare: cluster randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Psychiatr. 2007;191(5):420–426. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.036939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priebe S., Watzke S., Hansson L., et al. Objective social outcomes index (SIX): a method to summarise objective indicators of social outcomes in mental health care. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2008;118(1):57–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priebe S., Bogic M., Ajdukovic D., et al. Mental disorders following war in the Balkans: a study in 5 countries. Arch. Gen. Psychiatr. 2010;67(5):518–528. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priebe S., Omer S., Giacco D., et al. Resource-oriented therapeutic models in psychiatry: conceptual review. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2014;204(4):256–261. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.135038. [published Online First: 2018/01/02] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priebe S., Kelley L., Omer S., et al. The effectiveness of a patient-centred assessment with a solution-focused approach (DIALOG+) for patients with psychosis: a pragmatic cluster-randomised controlled trial in community care. Psychother. Psychosom. 2015;84(5):304–313. doi: 10.1159/000430991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priebe S., Golden E., Kingdon D., et al. NIHR Journals Library; Southampton (UK): 2017. Effective Patient–Clinician Interaction to Improve Treatment Outcomes for Patients with Psychosis: a Mixed-Methods Design. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priebe S., Fung C., Sajun S.Z., et al. Resource-oriented interventions for patients with severe mental illnesses in low-and middle-income countries: trials in Bosnia-Herzegovina, Colombia and Uganda. BMC Psychiatr. 2019;19(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12888-019-2148-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez B.F., Bruce S.E., Pagano M.E., et al. Relationships among psychosocial functioning, diagnostic comorbidity, and the recurrence of generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and major depression. J. Anxiety Disord. 2005;19(7):752–766. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleem S, Baig A, Bird VJ, et al. A mixed methods exploration of structured patient-clinician communication with a solution focused approach (DIALOG+) in community treatment of patients with common mental health disorders in Pakistan. under review.

- Vant Hof E., Cuijpers P., Waheed W., et al. Psychological treatments for depression and anxiety disorders in low-and middle-income countries: a meta-analysis. Afr. J. Psychiatr. 2011;14(3):200–207. doi: 10.4314/ajpsy.v14i3.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . World Health Organization; 2017. Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates. [Google Scholar]

- Zanello A., Berthoud L., Ventura J., et al. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (version 4.0) factorial structure and its sensitivity in the treatment of outpatients with unipolar depression. Psychiatr. Res. 2013;210(2):626–633. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.07.001. [published Online First: 2013/07/26] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang A., Franklin C., Jing S., et al. The effectiveness of four empirically supported psychotherapies for primary care depression and anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2019;245:1168–1186. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]